Abstract

Given the steady increase of ethnic diversity in the US, greater numbers of people develop the ability to negotiate ethnic boundaries and form multiple ethnic identifications. This paper explores the relationship between intra-ethnic and cross-ethnic relationships—defined in terms of social networks—and patterns of ethnic self-identification among New York City (NYC) Latinos. Drawing on theory and methods from the field of social network analysis, one hypothesis is that people with ethnically heterogeneous networks are more likely to have multiple ethnic identifications than people with ethnically homogeneous networks. The paper further explores the relationship between network ethnic diversity and the demographic and network characteristics of Latinos from four different Latino subgroups: Colombian, Dominican, Mexican, and Puerto Rican. A total of 97 NYC Latinos were administered ethnic self-identification and factorial surveys, and a social network questionnaire. Blau’s diversity index was used to compute the level of ethnic diversity present in participants’ networks. Results provided modest support for the hypothesis that multiple ethnic identifications would be associated with network ethnic diversity. There were important differences between the four groups in terms of network diversity, network ethnic composition, and ethnic self-identification. Results provide some support for the notion that weak ties introduce diversity to social networks.

1. Introduction

New York City (NYC) is among the growing number of cities in the US where national minority groups comprise the majority of the local population [1]. Many communities in NYC are ethnically heterogeneous, with foreign-born making up half or more of the population. Advances in communication and transportation facilitate the physical and virtual movement of people, their intentions, ideas, resources, and identities, and many engage in constant transnational resource and information exchange.

With the concentration of people from diverse racial, ethnic and national backgrounds in NYC and other cities, more opportunities for inter-ethnic unions arise. The children born from these bonds will be ethnically mixed and will be conversant with multiple cultures, languages, and norms. To the extent that the traditional conceptions of ethnic groups include set boundaries and a certain level of internal homogeneity, what Maharidge calls the browning of America will change how we look at ethnic groups [2]. Understanding how people negotiate between the different ethnic groups of which they are part will grow in importance. What is key is that more than in any other moment in America’s history, people will be able to draw from a broader range of ethnic options that cross multiple ethnic and racial boundaries.

Ethnic diversity, particularly in urban communities, promotes the formation of cross-ethnic group networks based on mutual interests. The resources that move along these networks can serve to strengthen relations between groups while contributing to the weakening of ethnic group boundaries. The systematic study of these networks can shed some light on how ethnic identity is formed, retained, invoked and weakened vis á vis social interactions with in-group and out-group members.

In this paper I explore intra-ethnic and cross-ethnic relationships—defined in terms of social networks—and patterns of ethnic self-identification among NYC Latinos. NYC Latino subgroups differ across a range of variables, especially racial composition, immigrant status, and economic outcomes. Within NYC, while many Latinos share the same neighborhoods, many others settle in ethnic enclaves with co-ethnics. Nevertheless, the considerable diversity of the Latino panethnicity makes this group particularly interesting for studying the relationship between network ethnic diversity and ethnic self-identification. Though often lumped under the same umbrella, Latinos experience multiple levels of cross-ethnic relations. Within the panethnicity, cross-ethnic relations test and contribute to the formation of a Latino panethnicity. Beyond the panethnicity, US Latinos may draw upon specific regional and nationality-based ethnic categories in addition to the all-encompassing Latino category. The ethnic options available to Latinos are shaped by a constellation of factors, including immigration histories and racialization processes. While Latinos are racialized as non-White according to the US Black-White racial binary, marked racial diversity exists within the panethnicity, one that is fraught with racial tensions [3]. The US racial system produces varying self-identification patterns as it interfaces with those categorization systems that Latino immigrants bring with them. Thus race is among the variables that complicate cross-ethnic and intra-ethnic interactions among Latinos.

2. Cross-Ethnic Relationships and Ethnic Self-Identification

Ethnicity is a social categorization most salient in heterogeneous societies and results from the interactions of groups from different cultural or ethnic origins [4]. Cohen once wrote: “ethnicity has no existence apart from interethnic relations” [5] (p. 389). In highly ethnically diverse urban environment such relations may result in unique outcomes. On the one hand, as more ethnic groups are available for comparison, ethnic group boundaries are strengthened (see Turner for a discussion of how this applies to ethnic identity [6]). This is consistent with Barth’s theorizing of ethnic group boundaries as persisting, even as members move across boundaries [7]. However, contact among ethnic groups, such as in economic exchanges and intermarriage, lead to cross-group relations that weaken ethnic group boundaries as people develop multiple ethnic identifications reflecting their life experiences and social environments. Whether ethnic group boundaries persist or diminish can depend on the presence of various structural constraints, for example, spatial and economic segregation.

It is perhaps easier to see how a person with two parents from different ethnic backgrounds can claim multiple ethnic identifications. They can adopt either their mother or their father’s ethnicity or develop a third, hybrid, flexible, bi-cultural identity out of the unique experiences and relationships that arise from straddling two cultural worlds [8,9,10,11]. For people with a single ethnic ancestry, the formation of more than one ethnic identification is not always as straightforward. Multiethnicity can arise through linguistic or religious conversion, which in turn changes people’s social networks as they forge relationships that reinforce an adopted ethnicity [12]. Further, Jiménez has shown that people develop affiliative identities grounded in cross-ethnic and cross-racial experiences and relationships [13].

More commonly, multiple ethnic identifications emerge because group membership exists at multiple levels of inclusiveness. People can identify in terms of their national, racial, or regional affiliations. Each of these levels has corresponding ethnic markers. The ethnic labels that people use when invoking their ethnic identifications tend to be more specific, or less inclusive, as people come into daily contact with members of their own ethnic group [5,14,15,16]. For example, a Cuban woman can use the more inclusive label of Latina when interacting with members of non-Spanish speaking ethnic groups, Cuban with another Latina, or may use the more specific label of marielito (someone who came to the US from Cuba during the Mariel boatlift operation between April and September 1980) when addressing other Cubans [14].

In their study of ethnic identity switching among Latino high school students, Escbach and Gomez compared how the same students answered the question, “What is your origin or descent” in two different years [17]. Students in communities with a large Latino population were less likely to switch to non-Latino questionnaire categories than were students in communities with few Latinos. This finding underscores the situational nature of ethnicity; the ways in which social context and social relationships affect which identifications people use. Indeed, people switch their ethnic identifications depending on the social context [author]; networks of relationships are key sites for the contextual invocation of ethnic identifications.

3. Social Network Ethnic Diversity

This paper’s central argument is that our social environments—defined in terms of social networks—interact in important ways with our social identities, specifically our ethnic identities. Here I adopt the social network perspective advanced in the field of social network analysis (SNA). In this view, actors and their actions are embedded in a web of relational ties that both enable and constrain [18]. In social network terms, a social environment or social context can be defined as a lasting pattern of social connections. Here, my focus is on the pattern of social connections that surround one individual, also dubbed personal networks. Personal networks reflect the ethnic identifications people adopt throughout a lifetime and influence the identifications they invoke during interaction. Hence, not only are personal networks where people attain the cultural knowledge that informs their sense of belong to an ethnic group, they are also “crucial environments for the activation of schemata, logics, and frames” associated with specific ethnic identifications [19] (p. 283).

According to a structural interactionist framework, concerned with how social structures affect identities [20,21], social networks mediate between macro-structural conditions and individual cognition to explain patterns of ethnic identification. Network theory is considered an important approach for studying the link between individual actions and overarching structural processes [22]. Accordingly, I adopt a theoretical framework that highlights the role of social interaction in the formation of ethnic identifications; interactions embedded within particular structural conditions. Through participation in networks, people amass the cultural knowledge necessary to successfully adopt and invoke ethnic categories. In turn, self-identification reinforces relationships with people who share the same identification and provides a basis for differentiation from others who do not. Within immediate social networks people first come to think of themselves as part of “us” and distinct from “them”.

Recent research has shown that various social network characteristics, such as density, homogeneity, and bridging can predict the salience of social identities, including those tied to ethnicity [23,24,25]. Measuring the ethnic diversity (homogeneity or heterogeneity) of a personal network is particularly promising as a way to measure the salience of various ethnic identifications for people. But the study of social networks also provides a means by which to map the links between subjective and performative states like ethnic identification and people’s social environment.

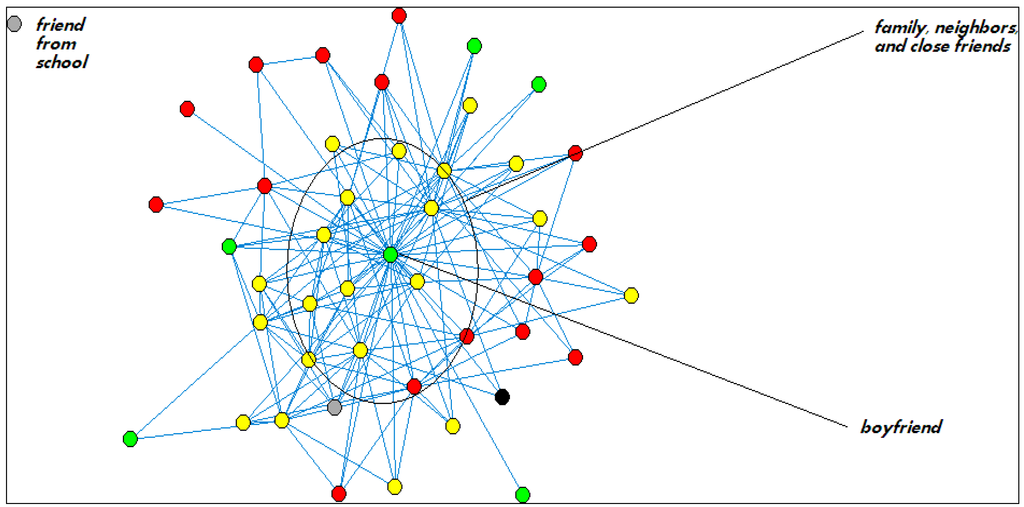

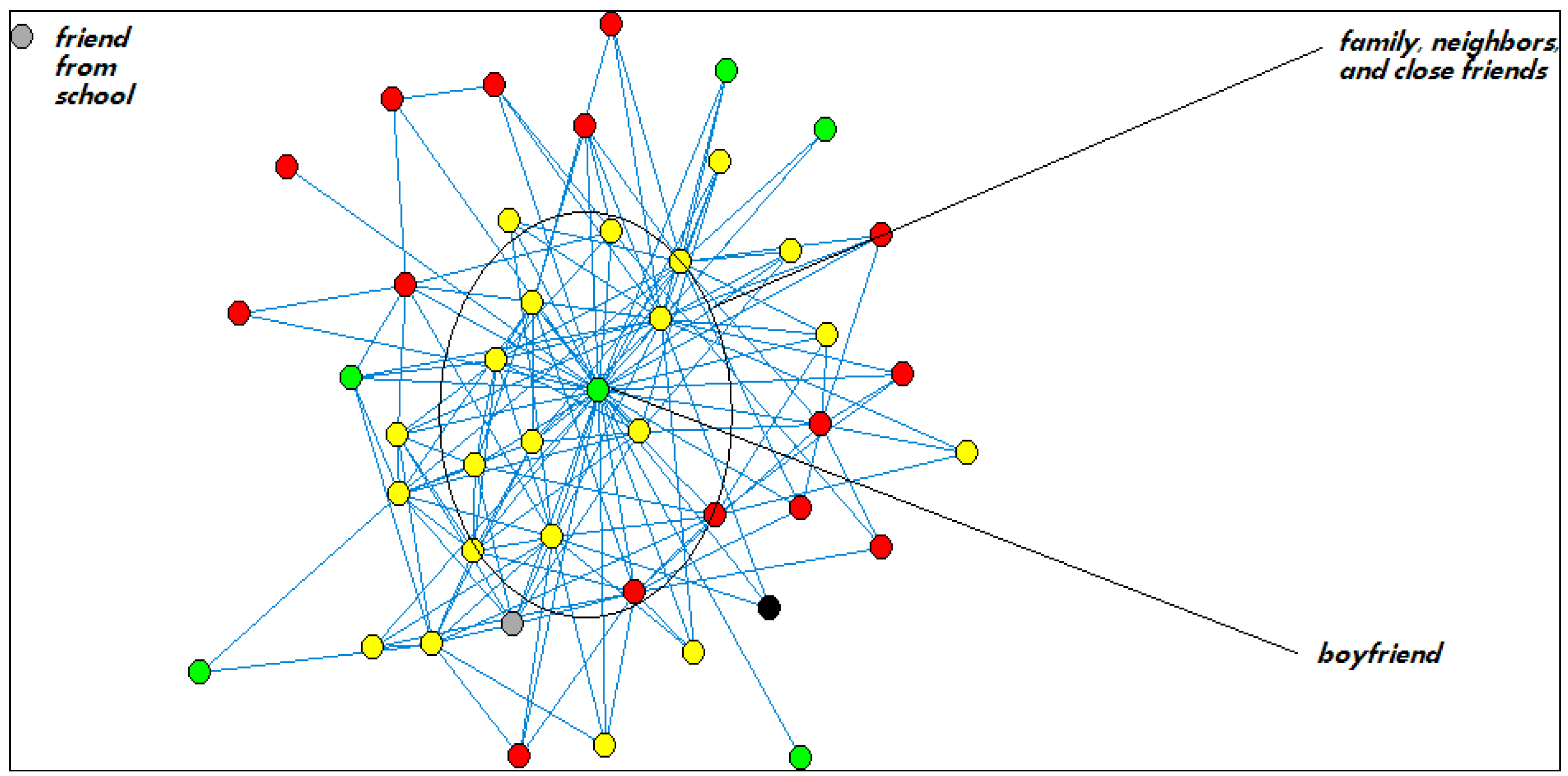

Many ethnic choices are made in interactions with members of immediate social networks. Here I explore how developing relationships across ethnic boundaries contributes to the development of multiple ethnic identifications or the propensity to switch among multiple ethnic options. Furthermore, I am interested in the relationship between the ethnic heterogeneity of networks and the demographic and network characteristics of Latinos from four different Latino subgroups. A key hypothesis is that people with ethnically heterogeneous personal networks (see Figure 1) are more likely to have multiple ethnic identifications than people with ethnically homogeneous networks (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Visualization of the ethnically heterogeneous network of a Dominican woman in this study.

Figure 1.

Visualization of the ethnically heterogeneous network of a Dominican woman in this study.

Note: Members of her network hailed from the US (red), the Dominican Republic (yellow), Puerto Rico (green) and others (black and grey). Reflective of her social environment, she reported using the following ethnic identifications: Latina, Dominicana, Hispana, Cibaeña, Capitaleña, Caribeña, Morenita, Dominicana-Americana, Española, Americana.

Figure 2.

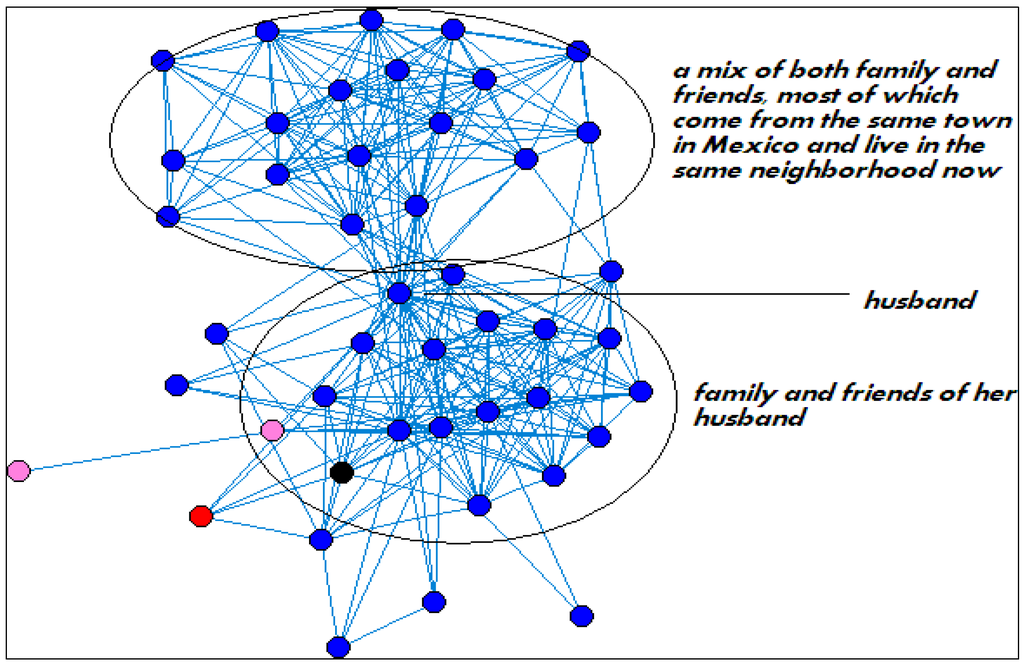

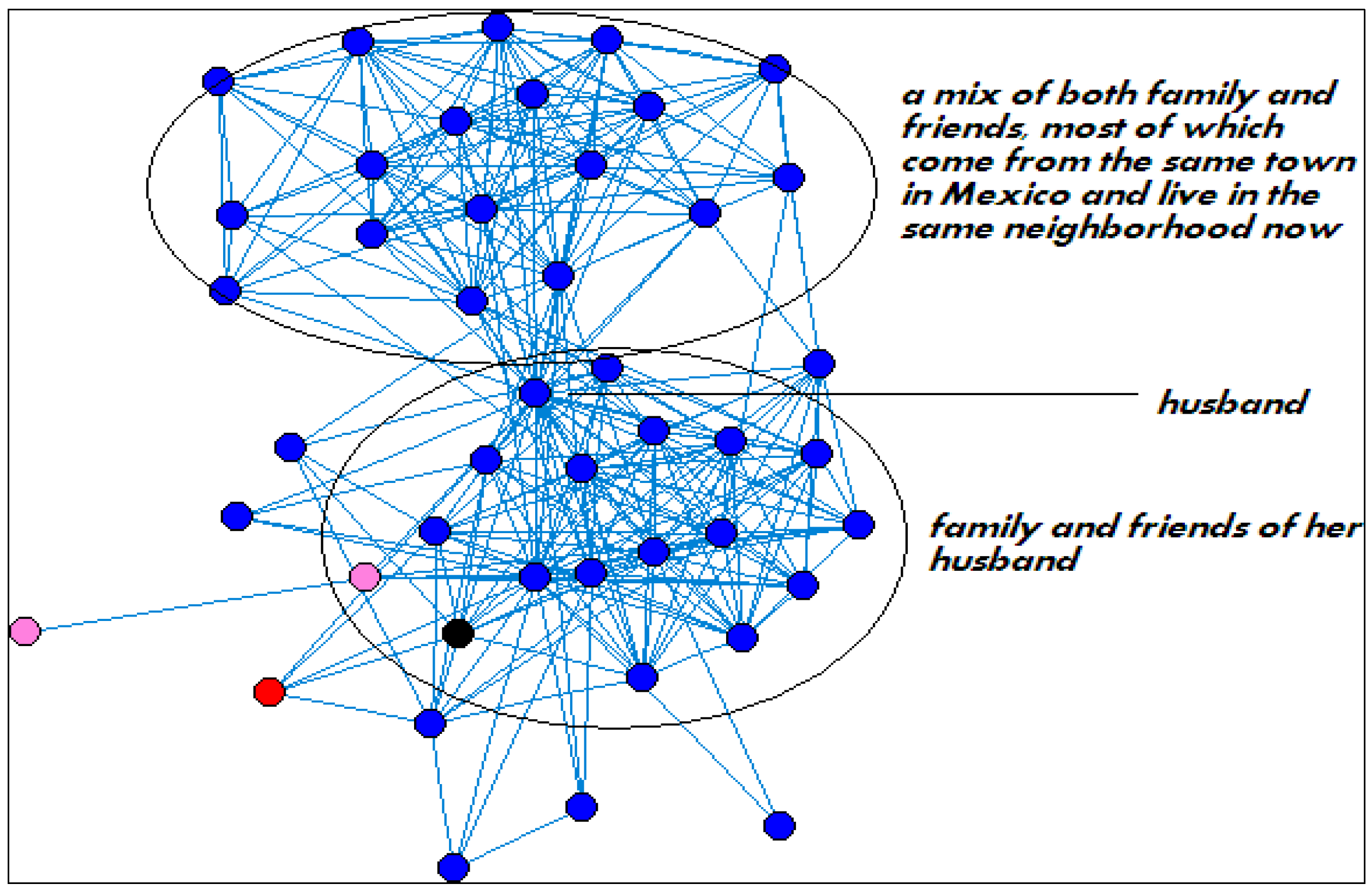

Visualization of the ethnically homogeneous network of a Mexican woman in this study.

Figure 2.

Visualization of the ethnically homogeneous network of a Mexican woman in this study.

Note: Most alters in her network are Mexican (blue). In contrast to the woman whose network is seen in Figure 1, she reported using fewer ethnic identifications: Mexicana, Latina, Tlapanecos, Hispana.

4. The Study

Members from each of the four largest sub-groups in NYC were recruited for this study: Colombians, Dominicans, Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans. I found participants though Craigslist, local Spanish-language newspapers, flyers posted in different neighborhoods, and word-of-mouth. A total of 117 people participated in social network and ethnic self-identification questionnaires, and an interview. Social network questionnaires were assessed for completeness, accuracy, and consistency. As such, 20 questionnaires were excluded from the final sample due to incompleteness or irregularities, mostly as a result of data entry errors (most participants entered their own answers into the computer-assisted questionnaire) (see Table 1). The final dataset included the responses and network statistics for 97 participants.

Table 1.

Sample demographic characteristics.

| % (N) | |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | |

| Dominican | 31 (30) |

| Colombian | 30 (29) |

| Mexican | 12 (12) |

| Puerto Rican | 27 (26) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 47 (46) |

| Male | 53 (51) |

| Race | |

| White/Blanca | 25 (24) |

| Black/Negra | 2 (2) |

| Brown/Morena | 55 (53) |

| Other | 18 (18) |

| Average age | 33 ± 13.63 |

| Foreign-born | 87 (85) |

| Total | 97 |

4.1. Ethnic Self-Identification and Factorial Survey

Participants were asked to think about the various ethnic identifications they used to identify themselves to others. They listed each of the categories and then ranked them according to how frequently they used each category. Next, participants were presented with a factorial survey. Factorial surveys present respondents with hypothetical situations (vignettes), testing factors that influence social judgments, in this case, social judgments about which ethnic identification is most appropriate in different contexts [26]. Vignettes are comprised of the randomly combined levels from factors of interest.1 The highest ranked identification from the ethnic self-identification ranking was a participants’ primary identification. In completing the factorial surveys, respondents judged whether in each scenario they would use their primary identification or some other identification. The ethnic self-identification list and ranking was used to operationalize multiethnicity, and the responses to the factorial surveys were used to operationalize ethnic identification switching.

4.2. Social Network Questionnaire

Using Egonet software for the computer-based collection of personal social network data [27], I elicited information about the composition of each participant’s network (e.g., percentage of network that is of a particular ethnic background) and about the structure of their network (e.g., the percentage of people in a participant’s network who know each other). First, participants (ego) answered a series of socio-demographic questions. In the second section of Egonet questionnaire, a free list name generator elicited the names of 45 people that the ego knew; network members are also called alters in the field of SNA. A known person was defined as someone the ego recognized by face and by name and who in turn recognized the ego by face and name. I further asked that they only list people they had known for at least two years and whom they could contact if they had to. In the third section, participants had to indicate the age, gender, nationality, race, relationship and closeness to each alter listed. Finally, participants rated the likelihood that alters would talk to each other in their absence. With this information, Egonet visualized alters as nodes connected by lines that represent the existing social ties between them. Using these visuals, I asked participants to discuss the role played by key members of their network, as well as distinctive features of their network (e.g., sparseness, cohesiveness, clusters).

5. Measures

5.1. Network Diversity

Blau’s index of diversity was computed using eight categories of the ethno-national origins of network alters [28]. Country of birth was used as a proxy for ethnic identification of network alters. Participants were asked if their alters were born in: (1) the United States, (2) Puerto Rico, (3) Dominican Republic, (4) Colombia, (5) Mexico, (6) Ecuador, (7) Cuba, and (8) Other. If participants selected “Other”, they had the option to enter the ethno-national identification of an alter. In the following analysis, I used the aggregated “Other” category to calculate Blau’s index scores rather than tallies of individual categories listed under “Other”. Egonet was used to calculate the percentage of alters who belonged to each of six ethnic/nationality categories. Accordingly, diversity scores were computed with the following formula:

where k = number of categories of the variable and p = percentage of individuals in each of the ethno-national categories. Higher levels of diversity would result in scores approaching 1. Scores approaching 0 denote low levels of diversity, with an uneven distribution of groups.

where k = number of categories of the variable and p = percentage of individuals in each of the ethno-national categories. Higher levels of diversity would result in scores approaching 1. Scores approaching 0 denote low levels of diversity, with an uneven distribution of groups.

5.2. Neighborhood Diversity

During the social network interview participants were asked for their neighborhood of residence, along with a brief description of the demographic composition in their residential surrounds. I then rated each neighborhood on a scale of 1 to 5 according to levels of diversity, with 1 being “no diversity” and 5 being “very high diversity”. My first-hand knowledge of each neighborhood, along with participants’ descriptions, was cross-referenced with American Community Survey data about neighborhood ethno-national composition. Thus, I developed a ranking of neighborhood diversity based on my qualitative assessment of census data and participants’ descriptions. Mirroring Blau’s index, neighborhoods were ranked as most diverse if large numbers of more than three ethnic groups occupied the location. The least diverse neighborhoods were those with large concentrations (>70%) of one ethnic group. For example, Manhattan’s Washington Heights (approximately 46% Dominican) was rated as less diverse than Jackson Heights, despite the fact that both contain large Latino immigrant populations [1]. Jackson Heights has a greater distribution of multiple Latino subgroups, including Colombian, Mexican, and Ecuadorian, in addition to significant numbers of South Asian immigrants. In contrast, at the time of the study, Washington Heights was (and continues to be) a prominent Dominican enclave, though in recent years other groups, including Euro-Americans have moved in.

5.3. Multiethnicity

Multiethnicity was measured by counting the number of distinct ethnic categories that people listed in their ethnic identification survey. Counts for either the “Latino” and “Hispanic” labels were combined into one category. Participants listed distinct nested categories (Latino, Dominican, Cibaeño), as well as categories denoting separate ethno-national groups.

5.4. Ethnic Identification Switching

Ethnic identification switching (EIS) was based on a count of the number of times that participants indicated that they would use an ethnic identification other than their primary ethnic identification across the various scenarios presented to them in the factorial survey.

6. Results

6.1. Test of Main Hypothesis

Using Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation, this paper tests the central hypothesis that the use of multiple ethnic identifications will be positively related to social network diversity. I examine the relationship between social network diversity and two related dependent variables: the number of ethnic categories participants reported using (multiethnicity) and ethnic identification switching (EIS). A summary of key findings from the correlation tests is shown in Table 2. EIS and multiethnicity were positively correlated, and while statistically significant, the correlation was weak (rs = 0.22, p = 0.03). This suggests that, as long as there are at least two options, the number of ethnic categories that people can draw on has minimal bearing on the act of switching ethnic identifications. There was modest support for the hypothesis that multiple ethnic identifications are positively associated with social network diversity. While no statistically significant relationship was found between social network diversity and EIS (rs = 0.14, p = 0.18), there was a weak positive association between the use of multiple ethnic identifications and social network diversity (r = 0.20, p = 0.056). One-way ANOVA’s revealed important differences between the four Latino groups in terms of average EIS (see Table 3). Group differences in the average number of times that participants switched between ethnic identifications were statistically significant (F = 2.93 df = 3, p = 0.03). Dominicans were considerably less likely to switch (M = 1.63 ± 1.8), while Mexicans had the highest average (M = 3.42 ± 3). Minimal group differences were found in the average number of ethnic identifications that participants reported having. Mexicans reported having a slightly higher number of ethnic categories (M = 4.83 ± 1.9), and Colombians (M = 4.34 ± 1.8) and Dominicans (M = 4.37 ± 2.2) the lowest. However, the group differences were not statistically significant (F = 0.226, df = 3, p = 0.878).

In what follows I present results providing further detail about intra- and cross-ethnic relationships among Latinos and the links of such relationships to ethnic identification. First, I cover findings about the relationship between multiethnicity, EIS and demographic and neighborhood variables. Then I examine specific relationships between social network diversity, and network composition, highlighting some important differences between the Latino groups considered in this study.

6.2. Multiethnicity and Ethnic Identification Switching

In addition to Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation run on continuous variables, independent samples t-tests or one-way ANOVA’s were done to determine differences between groups (e.g., men/women, those with or without children) in relation to multiethnicity and ethnic flexibility.

Table 2.

Multiethnity and Social Network Diversity: Summary of Main Findings.

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. EIS | ||||||||||||

| II. Multiethnicity | 0.22(0.03) * | |||||||||||

| III. Network Diversity | 0.14 (0.18) | 0.20 (0.56) * | ||||||||||

| IV. Neighrd. Diversity | 0.25 (0.04) * | −0.04(0.75) | 0.03 (0.10) | |||||||||

| V. Age | 0.07 (0.51) | −0.22 (0.03) * | −0.08 (0.46) | 0.00 (0.98) | ||||||||

| VI. COL Alters | 0.09 (0.36) | −0.05 (0.63) | −0.13 (0.19) | 0.38 (0.00) * | −0.03 (0.78) | |||||||

| VII. CUB Alters | −0.04 (0.67) | 0.01 (0.96) | 0.32 (0.002) * | −0.11 (0.35) | 0.04 (0.69) | −0.05 (0.60) | ||||||

| VIII. DR Alters | −0.27 (0.01) * | −0.06 (0.55) | −0.28 (0.01) * | −0.36 (0.00) * | −0.02 (0.82) | −0.38 (0.00) * | −0.07 (0.48) | |||||

| IX. ECU Alters | 0.16 (0.12) | 0.02 (0.84) | 0.27 (0.01) * | 0.11 (0.36) | −0.15 (0.14) | 0.09 (0.40) | 0.1 (0.32) | −0.17 (0.09) | ||||

| X. MX Alters | −0.09 (0.41) | −0.06 (0.56) | −0.13 (0.19) | 0.03 (0.82) | −0.00 (0.97) | −0.15 (0.14) | −0.11 (0.27) | −0.21 (0.03) | 0.27 (0.01) * | |||

| XI. PR Alters | 0.06 (0.53) | 0.01 (0.93) | 0.31 (0.002) * | −0.03 (0.82) | 0.14 (0.17) | −0.27 (0.01) * | 0.00 (0.10) | −0.15 (0.14) | 0-.21 (0.03) * | −0.23 (0.03) * | ||

| XII. Other Alters | 0.24 (0.02) * | 0.02 (0.87) | 0.51 (0.000) * | 0.15 (0.21) | −0.10 (0.31) | 0.10 (0.32) | 0.11 (0.29) | −0.34 (0.001) * | 0.29 (0.004) * | −0.04 (0.66) | −0.06 (0.57) | |

| XIII. US Alters | 0.15 (0.15) | 0.16 (0.13) | 0.06 (0.56) | −0.09 (0.45) | −0.02 (0.82) | −0.38 (0.00) * | 0.07 (0.47) | −0.34 (0.000) * | −0.15 (0.14) | −0.15 (0.13) | −0.01 (0.91) | −0.11 (0.23) |

* Statistically significant.

Table 3.

Mean number of ethnic identifications and EIS by ethnicity.

| Ethnicity of Participant | EIS | Multiethnicity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Colombian | 29 | 3.17 | 2.3 | 4.34 | 1.8 | |

| Dominican | 30 | 1.63 | 1.8 | 4.37 | 2.2 | |

| Mexican | 12 | 3.42 | 3.0 | 4.83 | 1.9 | |

| Puerto Rican | 26 | 3.08 | 2.8 | 4.54 | 1.7 | |

| Total | 97 | 4.5 | 1.9 | 4.52 | 1.90 | |

6.3. Gender, Age, Children, and Foreign-born Status

No significant differences between men and women were found with regard to EIS (t = −0.79, p = 0.43) and multiethnic identification (t = 1.0, p = 0.32). Age was negatively associated with multiethnic identification (r = −0.22, p = 0.03), but not at all related to the number of times that people switched between ethnic categories (r = 0.07, p = 0.51). There was a statistically significant difference between those with children and those without in terms of the number of ethnic identifications used (t = 2.37, df = 85, p = 0.02). People without children were more likely to report having used more categories to identify themselves ethnically to others. This relationship was likely mediated by age, since older participants were more likely to have children, but less likely to report using multiple ethnic identifications. Neither EIS nor multiethnicity was associated with participants’ foreign-born status. However, foreign-born participants were less likely to have US-born alters (F = 34.81, p = 0.01).

6.4. Race

The four main racial groups in this study—White, Black, Brown (moreno), and Other—differed, though marginally so, in the number of ethnic identifications used (F = 2.37, df = 3, p = 0.08). In short, the mean number of ethnic identifications was higher for people who identified as Brown than any other group, and especially in comparison to those who identified as White (MD = 1.16, p = 0.29) (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean number of ethnic identifications by racial group.

| Participant’s Self-Described Race | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| White/Blanca | 24 | 3.8 | 1.36 |

| Black/Negra | 2 | 4.0 | 0.00 |

| Brown/Morena | 53 | 4.9 | 2.16 |

| Other | 18 | 4.2 | 1.47 |

| Total | 97 | 4.5 | 1.9 |

6.5. Alter Ethnicity

No statistically significant relationships were found between alter ethnicity and the use of multiple ethnic identifications. However, the number of times that people switched between ethnic identifications across the range of scenarios presented to them in the factorial surveys was negatively associated with having Dominican alters (r = −0.27, p = 0.01). Furthermore, EIS was positively associated with having alters from “Other” ethnic backgrounds (r = 0.24, p = 0.02).

6.6. Neighborhood Diversity

There was a weak positive association between EIS and the level of diversity in participants’ neighborhoods (r = 0.25, p = 0.04). However, no correlation between multiethnic identification and neighborhood diversity was found (rs = −0.04, p = 0.75).

6.7. Social Network Diversity

6.7.1. Gender, Age, Children, and Foreign-Born Status

Tests of association were also conducted to examine the relationship between social network diversity, as defined by Blau’s diversity index, and a range of demographic and network characteristics. No statistically significant relationships were found between social network diversity and gender, age, foreign-born status, and neighborhood diversity.

6.7.2. Ethnicity, Race, and Homophily

Clearer patterns emerged in the relationship between social network diversity and ethnicity and race. Statistically significant differences were found in the levels of network diversity among Dominicans, Colombians, Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans (t = 3.70, p = 0.02). 2 In particular, post hoc tests revealed that there was a statistically significant difference between Puerto Ricans and Mexicans (MD = 0.16, p = 0.05). Indeed, Mexicans had the least ethnically diverse networks, followed by Dominicans. Puerto Ricans’ social networks were the most ethnically diverse (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Mean Blau diversity index score by ethnicity.

| Ethnicity of Participant | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dominican | 30 | 0.47 | 0.11 |

| Colombian | 29 | 0.53 | 0.20 |

| Mexican | 12 | 0.41 | 0.20 |

| Puerto Rican | 26 | 0.57 | 0.17 |

| Total | 97 | 0.51 | 0.18 |

The ethnic composition of participants’ networks was also related to network diversity. First, one-way ANOVA’s showed evidence of ethnic homophily given that there were significant between-group differences in the percentage of same-ethnicity alters. For each ethnic group in this study, Table 6 shows the distribution of alters’ ethnic backgrounds.

Thus Puerto Ricans had more Puerto Ricans in their networks than other groups did, Dominicans had more Dominicans in their networks, and so on. Of note, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans in this study tended to have more US-born network alters than the other groups did. Beyond this, network diversity was negatively associated with having Dominican alters (r = −0.28, p = 0.01), and positively associated with having alters from “other” backgrounds (r = 0.51, p = 0.000), Cuban alters (r = 0.32, p = 0.002) and Ecuadorian alters (r = 0.27, p = 0.01) (see Table 2). Complimentary to the finding about Dominican alters and network diversity, the percentage of Dominican alters was negatively associated with the percentage of US-born alters (r = −0.34, p = 0.000). The results suggest that Dominican participants tended strongly towards ethnic homophily and homogenous networks (Dominican-dominant) as compared to other groups in this study.

Table 6.

Distribution of alters’ ethnic backgrounds for each ethnic group.

| Ethnic background of alters: % of all alters (N = 97) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity of Participant | CO | CUB | DR | ECU | MX | OTH | PR | US |

| CO | 48 | 0.09 | 2 | 2 | 0.09 | 20 | 5 | 23 |

| DR | 1 | 0.06 | 59 | 1 | 0.07 | 7 | 5 | 27 |

| MX | 0.06 | 0.04 | 2 | 3 | 39 | 9 | 0.06 | 47 |

| PR | 1 | 0.07 | 11 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 11 | 33 | 44 |

| Mean | 12.52 | 0.07 | 18.50 | 1.51 | 9.80 | 11.75 | 10.77 | 35.25 |

| SD | 23.66 | 0.02 | 27.33 | 1.27 | 19.47 | 5.74 | 15.01 | 12.01 |

With regard to the racial composition of participants’ networks, the percentage of network members who were racially identified by participants as Brown, was negatively associated with network ethnic diversity (r = −0.25, p = 0.01). Conversely, the percentage of network members racially identified as Black was positively associated with network diversity (r = 0.25, p = 0.05). When considering the percentages of different racial groups present in participants’ networks, it is clear that greater numbers of white alters is related to decreased numbers of Black, Brown, and “other” racial groups in participants’ networks. The pattern is particularly notable between White and Brown alters. There was a moderately strong, negative association between having White and Brown alters (r = −0.64, p = 0.01) (see Table 7). Besides its negative correlation to White alters, the presence of Black alters was not associated with either an increase or decrease in the percentage of other racial groups. On the other hand, the percentage of alters who were racially identified as Brown was negatively associated with “other” racial groups (r = −0.37, p = 0.01). Of note, participants were asked to rate how close they felt to each of their network members. 3 There was a weak, but statistically significant negative association between the percentage of alters that participants felt “very close” to and the percentage of Black alters (r = −0.20, p = 0.004).

Table 7.

Pearson’s correlation matrix: network ethnic diversity and network racial composition.

| Variables | I | II | III | IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Network diversity | ||||

| II. Pct of white alters | 0.04 | |||

| III. Pct of black alters | 0.25 * | −0.32 ** | ||

| IV. Pct of brown alters | −0.25 * | −0.64 ** | −0.12 | |

| V. Pct of “other” race alters | 0.12 | −0.35 ** | −0.03 | −0.37 ** |

* Correlation is significant at 0.05 level (two-tailed); ** Correlation is significant at 0.01 level (two-tailed).

6.8. Neighborhood Diversity

Dominican and Colombian alters were found to be related to neighborhood diversity. Dominican alters were negatively associated with neighborhood diversity (r = −0.36, p = 0.002), while Colombian alters were positively associated with neighborhood diversity (r = 0.38, p = 0.001). These findings are consistent with the diversity profile of the NYC neighborhoods where either Colombians or Dominicans are found in greatest numbers. For example, the largest concentration of Colombians is found in Jackson Heights, Queens, a neighborhood where no one group dominates, and which includes significant numbers of Mexicans, Ecuadorians, and South Asians [29]. In contrast, in Washington Heights, Manhattan, with the highest concentration of Dominicans, the percentage of Dominicans nears 50% [1].

6.9. Other Variables

Finally, the most diverse networks were those that had alters who lived in the US (r = 0.33, p = 0.001). In other words, transnational ties were negatively associated with network diversity for participants with Colombian alters abroad (r = −0.28, p = 0.01), and for those with Dominican alters abroad (r = −0.33, p = 0.001). Participants were also asked to indicate the type of relationship they had to each alter (e.g., spouse, blood relative, co-worker). As would be expected, the percentage of blood relatives in participants’ networks was negatively associated with network ethnic diversity (r = −0.33, p = 0.001). Moreover, the percentage of alters who participants felt “very close” to was negatively associated with network diversity (r = −0.31, p = 0.002). This was the only statistically significant relationship found between closeness to alters and network diversity. It is quite likely that many of those alters who participants felt very close to were indeed blood relatives4. In addition, the percentage of alters who participants “met through a third person” was positively associated with network diversity (r = 0.22, p = 0.01). Further, there was a positive association between the percentage of alters met though others and the percentage of alters who participants were “not close” with (r = 0.27, p = 0.01). Together, these findings hint to the possible role played by weak ties in increasing the ethnic diversity of people’s networks.

7. Discussion

This paper examined the relationships between ethnic identification, ethnic diversity, and the composition of Latino New Yorkers’ social networks. In doing so, it has provided a profile of the cross-ethnic and cross-racial relationships that Latinos in NYC develop.

7.1. Multiethnicity and Ethnic Identification Switching

Overall, few firm conclusions about patterns of ethnic self-identification among the Latinos in this study can be made. However, the results point to a number of areas worth further exploration. There were key differences between the Latino groups in the number of times participants reported switching between ethnic identifications. Dominicans were markedly less likely to switch across contexts (see more below), while Mexicans were more so. Further research is needed to tease out why the rates are higher for Mexicans. One promising avenue is to determine whether higher reports of ethnic identification switching among Mexicans reflect the precariousness of Mexican identification—and the need for flexibility—in a national context were Mexicans are popularly associated with undocumented immigrant status. The Pew Hispanic Center estimates that 59% of undocumented immigrants in the US are from [30], while just under half of the Mexican population in the US has legal immigration status [31]. In NYC Mexicans have the lowest rates of naturalization [29]. The use of categories other than Mexican may serve to deflect scrutiny and negative associations made of this group (author, under review).

Younger people—particularly without children—tended to report using more ethnic identifications than older people. However, because age was not associated with network ethnic diversity in this study, it cannot be concluded that the diversity of young people’s networks played a role in this. Instead, the finding is consistent with other research suggesting that ethnic identity formation is in flux earlier in life and that as people move through the life course, ethnic self-concepts become more fixed [32]. Relatedly, the process of imparting to children coherent cultural norms and expectations associated with particular ethnicities may encourage parents to adopt more fixed ethnic self-identifications. Furthermore, because older participants had less US-born people in their networks it may be that knowing more US-born (i.e., American) people encourages the adoption and use of multiple ethnic identifications.

In contrast, having Dominican alters was negatively related to EIS. In other words, through a range of contexts, Dominicans tended to identify exclusively as Dominican, as opposed to, say, Latino, Caribbean or American. Across multiple variables, the picture that emerges for Dominicans is that they had less diverse—more Dominican-dominant—immigrant-oriented networks. The social environments of many Dominicans in this study were such that the use of ethnic identifications other than “Dominican” was perhaps unnecessary or discouraged. Note that no significant relationship was found between multiethnicity and Dominican alters. Thus, it is not necessarily that Dominicans in this study did not develop multiethnicity. Rather, it is possible that the social networks of Dominicans encourage a strong attachment to Dominican identification. With a total population of 576,701, Dominicans are the largest immigrant group in NYC [1]. Most settle in neighborhoods with significantly large numbers of Dominicans (e.g., Washington Heights in Manhattan, Corona in Queens) where daily social and economic activities take place with co-ethnics, with reduced opportunities for forming cross-ethnic relationships. Indeed, as this study has found, neighborhood diversity was negatively associated with having Dominican alters. Population size, along with residence patterns and immigrant status, are factors known to play an important role on ethnic homophily [33].

On the other hand, having alters of “Other” ethnic backgrounds was positively related to EIS. For some participants the “Other” category was directly tied to one ethnic group. However, for most it was a catch-all category that included several ethnic groups. Thus, just as having Dominican-dominant social networks discouraged switching, having a social network in which multiple ethnic groups are represented encouraged greater flexibility of identification. Having relationships with others of multiple ethnic backgrounds may attune people to the situational nature of ethnicity and the advantages that come with adapting to a range of cultural contexts. This finding points to the limits of the diversity measure used in this study. No relationship was found between multiethnicity or EIS and network diversity. The diversity measure was based on the eight alter ethnic categories used in this study, seven out of eight of which were Latino subgroup categories. The “Other” ethnic group category may be capturing more fully the extent of ethnic diversity in people’s networks, since it included non-Latinos from the Caribbean, Europe, Asia, and Africa. This may also help explain why neighborhood diversity—which did account for non-Latino groups—was positively associated with EIS while network ethnic diversity was not.

A final notable finding with regard to ethnic self-identification was that participants who racially identified as Brown—which can be construed as “mixed-race”—had higher numbers of ethnic identifications, particularly in comparison to those who identified as White. In a society where racialization processes result in a privileged status for Whites in relation to non-Whites, Brown or “mixed-race” people may find that adopting multiple ethnic identifications facilitates the negotiation of racial boundaries to their advantage. This is an option that is not so readily available to darker-skinned people [34]. Unfortunately, there were too few participants who identified as Black to detect any effects of Black racial identification on multiethnic identification or EIS.

7.2. Social Network Ethnic Diversity

Among the 97 Latinos who participated in this study, Latino-Latino relationships were common. Yet members of the four Latino subgroups studied here differed in the extent to which they had co-ethnic and cross-ethnic ties. For example, Puerto Rican participants were more likely to have US-born contacts than members of other groups, whereas for Dominicans, the average percent of Dominicans in their networks neared 60%.

Mexicans had the least ethnically diverse networks, followed by Dominicans. Interestingly, while overall the social networks of Mexicans were the least diverse, the Mexican participants tended to have more US-born contacts in their networks. Likely, this finding is a consequence of sampling rather than suggestive of individual networks evenly split between Mexican and American contacts. In the small sample of 12 Mexicans, there were a few participants whose networks were nearly completely dominated by Mexican alters. Yet, such participants, all of whom were first generation immigrants living in Mexican communities, were much more difficult to recruit. Instead, most of the Mexicans who participated in the study were second—and later generation immigrants with strong ties to American culture and relationships.

Though participants who identified as Brown reported using more ethnic identifications, network diversity was negatively related to having Brown alters. Additionally, having Brown alters was significantly linked to having less White alters. One caveat is that participants had to list a limited set of names and choose among mutually exclusive racial categories. Thus, more of one racial or ethnic group necessarily results in less of another ethnic or racial group. Still, because a majority of participants identified as Brown (53%), the greater numbers of Brown alters and may be pointing to racial homophily in participants’ networks, with consequences for overall network ethnic diversity. Consistent with this, the percentage of Black alters was positively related with network diversity. Black alters were further negatively correlated with “very close” ties, suggesting that while Black network members contributed to the ethnic diversity of participants’ networks, these ties were weak. Indeed, this study finds that weak ties may play a role in increasing network diversity. Given this, the weak or nonexistent relationship between the ethnic self-identification variables and network diversity, raises the question of whether strong, ethnically diverse ties are more important to the development of multiple ethnic identifications than weak, ethnically diverse ties.

8. Limitations

The data were collected from a relatively small purposive sample and cannot be generalized to the broader population of the Latino subgroups that were the focus of this paper, and certainly not to Latinos more broadly. Mexicans and Latino Blacks were particularly underrepresented in this study. As such, because the sample was small and non-representative, the p-values must be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, given the number of potential predictors of multiethnic identification, a larger sample size would have been appropriate for multiple regression analysis. While this study’s univariate analyses yielded promising results, future research should extend analysis to include multiple regression. Using multiple regression, future research should test the specific effects of social network diversity on multiethnicity, controlling for variables that include neighborhood diversity and individuals’ sociodemographic characteristics.

The measures also had their limitations. Multiethnicity, for example, was measured based on the number of distinct ethnic categories that people reported using. As such, the approach did not directly measure the strength of, nor capture subjective feelings about, the various ethnic identifications that participants listed. Existing measures of ethnic identity or bi-culturalism may have better assessed whether multiethnicity was in fact salient for participants in order to better gauge the relationship between network ethnic diversity and ethnic self-identification.

9. Conclusions

The results of this study provide some support for the hypothesis that multiple ethnic identifications are related to ethnic network diversity. Not enough is known about whether people develop multiple ethnic identifications after exposure to many diverse others, or if having a fluid sense of ethnic self and claiming multiple ethnicities leads people to form diverse networks. Among the Latinos in this study, it is likely that the relationship between network diversity and ethnic self-identification is stronger for some groups than others, in accordance with the distinct configurations of demographic characteristics found among US Latino subgroups.

Acknowledgments

Data collection for this project was funded by National Science Foundation Award No. BCS-0417429, awarded to Christopher McCarty and José Luis Molina, and by a National Science Foundation Dissertation Improvement grant awarded to me. Analysis and writing was supported by a grant from the Gastón Institute for Latino Public Policy and Community Development. I am grateful to Christopher McCarty and José Luis Molina for their assistance throughout the data collection phase of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey. 2012. Available online: http://factfinder2.census.gov (accessed on 26 February 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Maharidge, D. The Coming White Minority: California, Multiculturalism, and America’s Future; Vintage Books, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut, R.G. Pigments of Our Imagination: On the Racialization and Racial Identities of “Hispanics” and “Latinos”. In How the U.S. Racializes Latinos: White Hegemony and Its Consequences; Cobas, J.A., Duany, J., Feagin, J.R., Eds.; Paradigm: Boulder, CO, USA, 2009; pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- DeVos, G.A.; Suarez-Orozco, M. Status Inequality: The Self in Culture; Princeton University Press: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A. Introduction: The Lesson of Ethnicity. In Urban Ethnicity; Cohen, A., Ed.; Tavistock Publications: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.C. Social Categorization and the Self-Concept: A Social Cognitive Theory of Group Behavior. In Advances in Group Processes: Theory and Research; Lawler, E.J., Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, UK, 1985; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, F. Introduction. In Ethnic Groups and Boundaries; Little Brown: Boston, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, A.M. Bicultural Social Development. Hispanic J. Behav. Sci. 2006, 28, 467–497. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation. Appl. Psychol.—Int. Rev. 1997, 46, 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Spickard, P.R.; Fong, R. Pacific Islander American and Multiethnicity: A Vision of America’s Future. Soc. Forces 1995, 73, 1365–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, C.W.; Stephan, W.G. After intermarriage: Ethnic identity among mixed heritage Japanese-Americans and Hispanics. J. Marriage Fam. 1989, 51, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, D.L. Ethnic Identity. In Ethnicity: Theory and Experience; Glazer, N., Moynihan, D.P., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, T.R. Affiliative ethnic identity: a more elastic link between ethnic ancestry and culture. Ethnic Racial Stud. 2010, 33, 1746–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, J. Constructing Ethnicity: Creating and Recreating Ethnic Identity and Culture. Soc. Probl. 1994, 41, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, S. The Transformations of Tribe: Organization and Self-Concept in Native American Ethnicities. Ethnic Racial Stud. 1988, 11, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufert, J.M. Situational Identity and Ethnicity among Ghanaian University Students. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 1977, 15, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschbach, K.; Gomez, C. Choosing Hispanic Identity: Ethnic Identity Switching among Respondents to High School and Beyond. Soc. Sci. Quart. 1998, 79, 74–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P. Culture and Cognition. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1997, 23, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S.; Burke, P.J. The Past, Present, and Future of an Identity Theory. Soc. Psychol. Quart. 2000, 63, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S.; Serpe, R.T. Commitment, Identity Salience and Role Behaviour: Theory and Research Example. In Personality, Roles, and Social Behavior; Ickes, W., Knowles, E.S., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Goss, J.; Lindquist, B. Conceptualizing International Labour Migration: A Structural Perspective. Int. Migr. Rev. 1995, 29, 317–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Federico de la Rúa, A. Networks and Identifications: Towards a relational approach of social identity. Int. Sociol. 2007, 22, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbers, M.; Molina, J.L.; McCarty, C. Personal Networks and Ethnic Identifications: The Case of Migrants in Spain. Int. Sociol. 2007, 22, 721–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, D.; Pals, H. Motives and Contexts of Identity Change: A Case for Network Effects. Soc. Psychol. Quart. 2005, 68, 289–315. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, P.H.; Noch, S.L. Measuring Social Judgments: The Factorial Survey Approach; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty, C. Egonet: Software for the Collection of Egocentric Network Data. Available online: http://sourceforge.net/projects/egonet/ (accessed on 1 March 2014).

- Blau, P.M. Inequality and Heterogeneity; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Latin American, Caribbean & Latino Studies. The Latino Population of New York City, 1990–2010; Latino Data Project, Report 44; City University of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Passel, J.S.; Cohn, D. A Portrait of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States. Available online: http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/107.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2013).

- Passel, J.S. Estimates of the Size and Characteristics of the Undocumented Population. Available online: http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/reports/44.pdf (accessed on July 1 2013).

- Phinney, J.S. Ethnic Identity in Adolescent and Adults: Review of Literature. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Cook, J.M. Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks. Annu. Rev. Soc. 2001, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, M. Ethnic Options: Choosing Identities in America; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 1These factors included: a) social setting/resource at stake, b) language spoken by interlocutor, c) ethno-racial identity of interlocutor, d) status of interlocutor relative to respondent, an e) gender of interlocutor.

- 2Welch’s robust test of mean differences was used because the four Latino subgroups did not have equal variance in the network diversity variable, complicating the comparison of means. This violated ANOVA’s assumption of homogeneity of variances. Welch’s test makes adjustments that overcome this violation.

- 3The rating options were: “Not at all close”, “Not very close”, “Somewhat close”, “Close”, and “Very close”.

- 4The relationship between the percentage of network alters who were blood relatives and the percentage of alters who participants felt “very close” to was positively associated (r = 0.513, p = 0.01).

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).