From Zoomers to Geezerade: Representations of the Aging Body in Ageist and Consumerist Society

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Analyzing Images

There is a loose gearing, then, between social structures and what goes on in particular occasions of ritual expression… Participants…are often displayed in rankable order with respect to some visible property looks, height, …elaborateness of costume… and so forth—and the comparisons are somehow taken as a reminder of differential social position, … Thus, the basic forms…provide a peculiarly limited version of the social universe, telling us more, perhaps, about the special depictive resources of social situations than about the structures presumably expressed thereby ([16], p. 3).

3. Methodology

4. Portrayals of Seniors in the Media

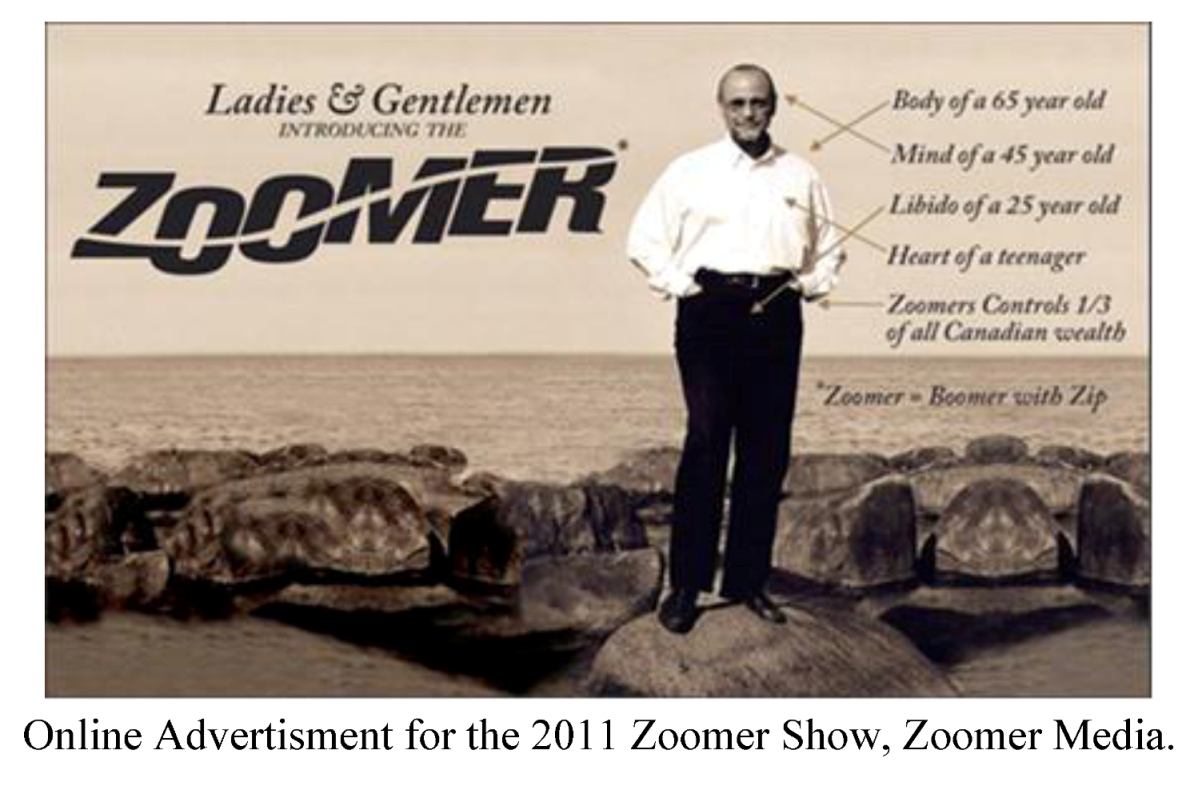

5. Positive Images

| Images of Older Adults | Zoomer Magazine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 2012 | April 2012 | May 2012 | June 2012 | July 2012 | |

| Positive Images | 26 | 23 | 25 | 29 | 30 |

| Negative Images | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Comical | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 26 | 25 | 29 | 32 | 34 |

| Percent Positive | 100% | 92% | 86% | 90% | 88% |

| Images of Older Adults | Zoomer Magazine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 2012 | April 2012 | May 2012 | June 2012 | July 2012 | |

| White | 23 | 23 | 26 | 30 | 34 |

| Non-White | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 26 | 25 | 29 | 32 | 34 |

6. Negative Images

| Images of older adults and young people in Advertisements | Zoomer Magazine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 2012 | April 2012 | May 2012 | June 2012 | July 2012 | |

| Images of older adults | 16 | 13 | 16 | 14 | 11 |

| Images of young people | 15 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 11 |

| Mix of older adults and young people | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 36 | 25 | 31 | 32 | 25 |

| Positive Images of older adults | 15 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 10 |

| Negative Images of older adults | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 16 | 13 | 16 | 14 | 11 |

| White older adults | 16 | 13 | 15 | 12 | 10 |

| Non-white older adults | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 16 | 13 | 16 | 14 | 11 |

7. The Geezerade Campaign

A couple of kids from our in-home daycare walked by and when they saw the photo, one kid said, ‘Oh look at the geezer.’ Then another kid said, ‘There’s a geezer on the screen’ and they all started to laugh and it just kind of made me cringe [52].

I would like to voice my support to end this promotion. I wrote an email to Irving on Wednesday May 4th after seeing the poster in question. Couche-tard called me the next day to explain that they had researched the word “geezer” and found nothing wrong with its use. I've been interviewed by Radio-Canada and they gave Couche-tard the opportunity to respond to my request of removing this promotion; they responded that they would not be removing the poster because young people are attracted to this images. I've asked different young people in the last day about the poster and they do not understand the message. I also wrote a letter to the editor at the Times & Transcript. Therefore, I am again, asking for the removal of these posters [57].

8. Conclusions

The ideal aging citizen is someone... that… remains youthful as long as possible, contributes to the economy as a smart consumer and as an active participant in productive activities, and stays healthy to avoid accessing healthcare and other public services ([20], p. 220).

Acknowledgements

References and Notes

- Coleman, A.D. The Grotesque in Photography; Summit Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, M. Rabelais and His World; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, M.; Smith, G. Analyzing Visual Data; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G. Gender Advertisements Revisited: A Visual Sociology Classic. Electron. J. Sociol. 1996, 2. Available online: http://www.sociology.org/content/vol002.001/smith.html (accessed on 16 July 2011).

- Catalani, C.; Minkler, M. Photovoice: A Review of the Literature in Health and Public Health. Health Edu.Behav. 2010, 37, 424–451, Also surprising given the increasing use of methodologies to analyze images such as Photovoice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, E.W. Orientalism, 25th anniversary ed; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, P.; Milic, M. Goffman’s Gender Advertisements Revisited: Combining Content Analysis with Semiotic Analysis. Visual Communic. 2002, 1, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffington, D.; Fraley, T. Skill in Black and White: Negotiating Media images of Race in a Sporting Context. J. Commun. Inquiry 2008, 32, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bytheway, B. Unmasking Age: The Significance of Age for Social Research; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lumme-Sandt, K. Images of Ageing in a 50+ Magazine. J. Aging Stud. 2011, 25, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylanne, V. Representing Ageing: Images and Identities; Palgrave Macmillan Houndmills: Basingstoke, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, H. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method; Prentice Hall Inc.: New Jersey, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann, M. Body images across the adult life span: Stability and change. Body Images 2004, 1, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.R.; Morrison, T.G. Stereotypes of Ageing: Messages Promoted by Age-Specific Paper Birthday Cards Available in Canada. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2005, 61, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. The Interaction Order. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Gender Advertisements; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1976; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Altheide, D.L. Ethnographic content analysis. Qual. Sociol. 1987, 10, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A.L. Grounded theory research: Procedures, Canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, K. Aging and the Media: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. Calif. J. Health Promot. 2007, 5, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rozanova, J. Discourse of Successful Aging in the Globe and Mail: Insights From Critical Gerontology. J. Aging Stud. 2010, 24, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.B.; Harwood, J.; Williams, A.; Ylänne-McEwen, V.; Wadleigh, P.M.; Thimm, C. The Portrayal of Older Adults in Advertising: A Cross-National Review. J. Lang Soc. Psychol. 2006, 25, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, T.R. The Journey of Life: A Cultural History of Aging in America; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, K.E. Three Faces of Ageism: Society, Image and Place. Ageing Soc. 2003, 23, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanova, J.; Northcott, H.C.; McDaniel, S. Seniors and Portrayals of Intra-Generational and Inter-Generational Inequality in the Globe and Mail. Can. J. Aging 2006, 25, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.M.; Carpenter, B.; Meyers, L.S. Representations of Older Adults in Television Advertisements. J. Aging Stud. 2007, 21, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.W.; Leyell, T.S.; Mazachek, J. Stereotypes of the Elderly in U.S. Television Commercials from the 1950s to the 1990s. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2004, 58, 315–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesperi, M.D. Introduction: Media, Marketing, and images of the older person in the information age. Generations 2001, 25, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, I.R.; Hyde, M.; Victor, C.R.; Wiggins, R.D.; Gilleard, C.; Higgs, P. Ageing in a Consumer Society: From Passive to Active Consumption in Britain; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vesperi, M.D. Forty-Nine Plus: Shifting images of Aging in the Media. In Reinventing Aging. Harvard School of Public Health-MetLife Foundation Initiative on Retirement and Civic Engagement; Center for Health Communication, Harvard School of Public Health, Baby Boomers and Civic Engagement, MetLife Foundation, 2003; pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, J.A. Specialty Magazines and the Older Reader. Generations 2001, 25, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, M.; Hepworth, M. Images of Aging. In Encyclopedia of Gerontology; Birren, J.E., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2007; pp. 735–742. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, J.A. Ageing Contested: Anti-Ageing Science and the Cultural Construction of Old Age. Sociology 2006, 40, 681–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Ylanne, V.; Wadleigh, P.M. Selling the ‘Elixir of Life’: Images of the Elderly in an Olivio Advertising Campaign. J. Aging Stud. 2007, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoomer Magazine; April 2012; p. 28.

- Zoomer Magazine; March 2012; p. 28.

- Zoomer Magazine; July 2012; p. 14.

- CBC. 1 in 6 Canadians is a visible minority: StatsCan—South Asians Top Chinese as Largest visible minority group. CBC News Online. 2 April 2008. Available online: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/story/2008/04/02/stats-immigration.html (accessed on 15 July 2012).

- Durkheim, E. The Division of Labor in Society; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grenier, A. Constructions of Frailty in the English Language, Care Practice and the Lived Experience. Ageing Soc. 2007, 27, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, F. Disney’s villains ‘give children negative images of the elderly’. Mail Online. 31 May 2007. Available online: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-458808/Disneys-villains-children-negative-images-elderly.html (accessed on 24 June 2011).

- McGlynn, K. This week in ridiculous stock photos: Old people using computers. The Huffingtton Post. 15 March 2011. Available online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/03/15/this-week-in-ridiculous-stock-photos_n_835869.html#s253779 (accessed on 24 June 2011).

- Milner, C.; Van Norman, K.; Milner, J. The Media’s Portrayal of Ageing. Global Population Ageing: Peril or Promise? World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GAC_GlobalPopulationAgeing_Report_2012.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2012).

- Thimm, C. Advertising and the Older Generation: Humourous or Degrading? In Media Res: A Media Commons Project. 23 March 2009. Available online: http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/imr/2009/03/22/advertising-and-older-generation-humerous-or-degrading (accessed on 24 June 2011).

- Dupuis-Blanchard, S.; Simard, M.; Gould, O.; Villalon, L. Les défis et les Enjeux Liés au Maintien à Domicile des Aînés: Une Étude de Cas en Milieu Urbain Néo-Brunswickois. In Rapport de Recherche; Université de Moncton: Moncton, New Brunswick, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Low, J.; Thériault, L.; Luke, A.; Hollander, M.; van den Hoonaard, D. Sustainable Home Support for Seniors in New Brunswick: Insights From Seniors and Social Workers. Department of Sociology, University of New Brunswick: Fredericton, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, B.J.; McQuarrie, E.F. Narrative and Persuasion in Fashion. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 368–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan. Benetton Pieta in AIDS Campaign. The Inspiration Room. 7 April 2007. Available online: http://theinspirationroom.com/daily/2007/benetton-pieta-in-aids-campaign/ (accessed on 17 July 2012).

- Grant, V. Still Shocking. The Kit Beauty & Fashion. 29 September 2011. Available online: http://www.thekit.ca/beauty/body/a-ck-history/ (accessed on 18 November 2012).

- Grotesque Animal Faces. TrendHunter Marketing. Available online: http://www.trendhunter.com/trends/grotesque-faces-hondas-use-original-parts-campaign (accessed on 18 November 2012).

- 40 Animalistic Ads. TrendHunter Marketing. Available online: http://www.trendhunter.com/slideshow/40-animalistic-ads#2 (accessed on 18 November 2012).

- MNT. What is progeria? Medical News Today. 13 May 2009. Available online: http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/146746.php (accessed on 18 July 2012).

- CBC. Geezerade ad campaign angers Moncton man. CBC News online. 24 May 2011. Available online: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/story/2011/05/24/nb-geezeraid-campaign.html (accessed on 17 July 2011).

- Replyz. Can anyone explain to me the Circle K marketing and ad campaign with slush / “Geezerade”? Replyz Tue. 24 May 2011. Available online: http://replyz.com/c/10563745-can-anyone-explain-to-me-the-circle-k-marketing-and-ad-campaign-with-slush-geezerade (accessed on 17 June 2011).

- Stop Geezerade campaign Facebook page. Available online: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Boycott-Irving-Gas-Circle-K-Stores-Ridicule-Of-seniors/122830681131794?sk=info (accessed on 17 June 2011).

- What if was called Coon-Ade? Medical News Today. 2009. Available online: http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/146746.php (accessed on 17 June 2011).

- Circle KKK-Hatin’ On The Old Folks. Geezerade protest poster since removed from the internet.

- Text of an e-mail message sent by Suzanne Dupuis-Blanchard to Couche-Tard on 11 May 2011, asking them to end the Geezerade campaign.

- D’Entremont, Y. Geezarade icy slush campaign gets cold shoulder. Halifax News Net. 15 June 2011. Available online: http://www.halifaxnewsnet.ca/News/2011-06-15/article-2586526/Geezarade-icy-slush-campaign-gets-cold-shoulder--/1 (accessed on 24 June 2011).

- Circle, K. Poster announcing end of the Geezerade campaign. Available online: http//www.circlekslush.com (accessed on 27 July 2012).

- Rozanova, J. Newspaper Portrayal of Health and Illness Among Canadian Seniors: Who Ages Healthily and at What Cost. Int. J. Ageing Later Life 2006, 1, 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komp, K.A. New images of Old Age: The Case of Third Age Societies. In Paper presented in the RC11 session: Images of Old Age at the 2nd ISA Forum of Sociology, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1–4 August 2012.

- Descartes, R. Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting the Reason and Seeking the Truth in the Sciences; P. F. Collier & Son Company: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo; Routledge and Keegan Paul: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1912. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Low, J.; Dupuis-Blanchard, S. From Zoomers to Geezerade: Representations of the Aging Body in Ageist and Consumerist Society. Societies 2013, 3, 52-65. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc3010052

Low J, Dupuis-Blanchard S. From Zoomers to Geezerade: Representations of the Aging Body in Ageist and Consumerist Society. Societies. 2013; 3(1):52-65. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc3010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleLow, Jacqueline, and Suzanne Dupuis-Blanchard. 2013. "From Zoomers to Geezerade: Representations of the Aging Body in Ageist and Consumerist Society" Societies 3, no. 1: 52-65. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc3010052

APA StyleLow, J., & Dupuis-Blanchard, S. (2013). From Zoomers to Geezerade: Representations of the Aging Body in Ageist and Consumerist Society. Societies, 3(1), 52-65. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc3010052