Abstract

Achieving gender equality is the Third Millennium Development Goal, and the major challenge to poverty reduction is the inability of governments to address this at grass root levels. This study is therefore aimed at assessing gender inequality as it pertains to socio-economic factors in (agro-) pastoral societies. It tries to explain how “invisible” forces perpetuate gender inequality, based on data collected from male and female household heads and community representatives. The findings indicate that in comparison with men, women lack access to control rights over livestock, land, and income, which are critical to securing a sustainable livelihood. However, this inequality remains invisible to women who appear to readily submit to local customs, and to the community at large due to a lack of public awareness and gender based interventions. In addition, violence against women is perpetuated through traditional beliefs and sustained by tourists to the area. As a result, (agro-) pastoral woman face double marginalization, for being pastoralist, and for being a woman.

1. Introduction

Gender equality and women’s empowerment is the third Millennium Development Goal [1] and is considered to be an essential component of sustainable economic growth and poverty reduction. However, governments continue to struggle with their capacity to translate gender policies into effective, actionable programs. Ethiopia, where gender inequality remains a pervasive feature of rural livelihoods, is no exception. As a patriarchal society that keeps women in a subordinate position [2,3], the country is characterized by disparities in the economic, social, cultural, and political positions and conditions of women [4].

Ethiopian pastoralists have traditionally been highly marginalized [4,5]. Critical development challenges for pastoralists include, resource degradation, worsening poverty, and lack of food security [6,7]. While all pastoralists suffer from marginalization, pastoralist women suffer from double marginalization, being both pastoralists and women [4,8,9,10]. Pastoral women have less decision making power within the home, while at the same time bearing a disproportionate burden of tasks and responsibilities.

Both men and women have vital roles in the continuation and adaptation of pastoral systems. Women play a central role as livestock keepers, natural resource managers, income generators, and service providers, tasks which, in of themselves, are influenced by gendered norms, values, and relations [11,12,13]. However, in spite of women’s contribution to pastoral life, they have only limited access to, and control over, key productive resources such as livestock and land. They also have limited access to healthcare, education, family planning, and reproductive health [5]. Moreover, the fundamental role of pastoral women in agriculture and livestock production has been systematically ignored and undervalued [12].

Gender based harmful traditions such as early marriage, Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), the beating of woman, and lack of access to education for girls are widespread in parts of Ethiopia, including the research site. Many of these violations are perpetuated from generation to generation, mother to daughter, due to a lack of public awareness, media attention, and availability and access to services. Women themselves are often reluctant to report violations, including physical attacks, since doing so is considered a sign of weakness. There is a norm that prescribes ‘a women should shoulder many challenges upon her’ to be considered as a ‘strong’ women. Traditional sayings like “Women and donkeys never complain about burdens”, instruct women not to report challenges. Consequently, there is little documented evidence regarding the level of domestic violence between men and women in pastoralist households.

The lack of attention to gender inequality in pastoral society renders it invisible. This is compounded by a reluctance to address the gender dimensions of pastoral peoples’ lives, as to do so is seen as “interfering with culture”. While the Ethiopian government has recognized the seriousness of gender inequality, it has failed to address the issue within the context of pastoralist society.

In general, research on pastoral communities is very limited and absent of any gender analysis. This study addresses that gap by assessing gender inequality in pastoral areas using the Harvard Gender Analysis Framework. In doing so, we empirically examined the difference between female and male-headed households in terms of select socio-economic variables. Specifically, we address the following research questions:

- What are the causes of gender inequality in (agro-) pastoral societies?

- What is the extent of gender inequality in terms of selected socio-economic variables?

The remainder of this paper is organized by methodological framework, findings and discussion, and conclusions.

3. Methodology

3.1. Description of the Study Area

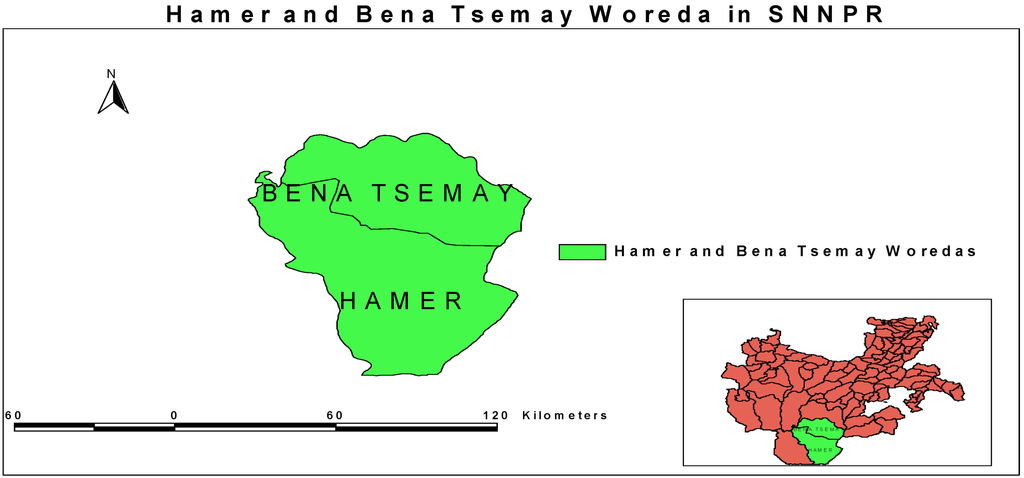

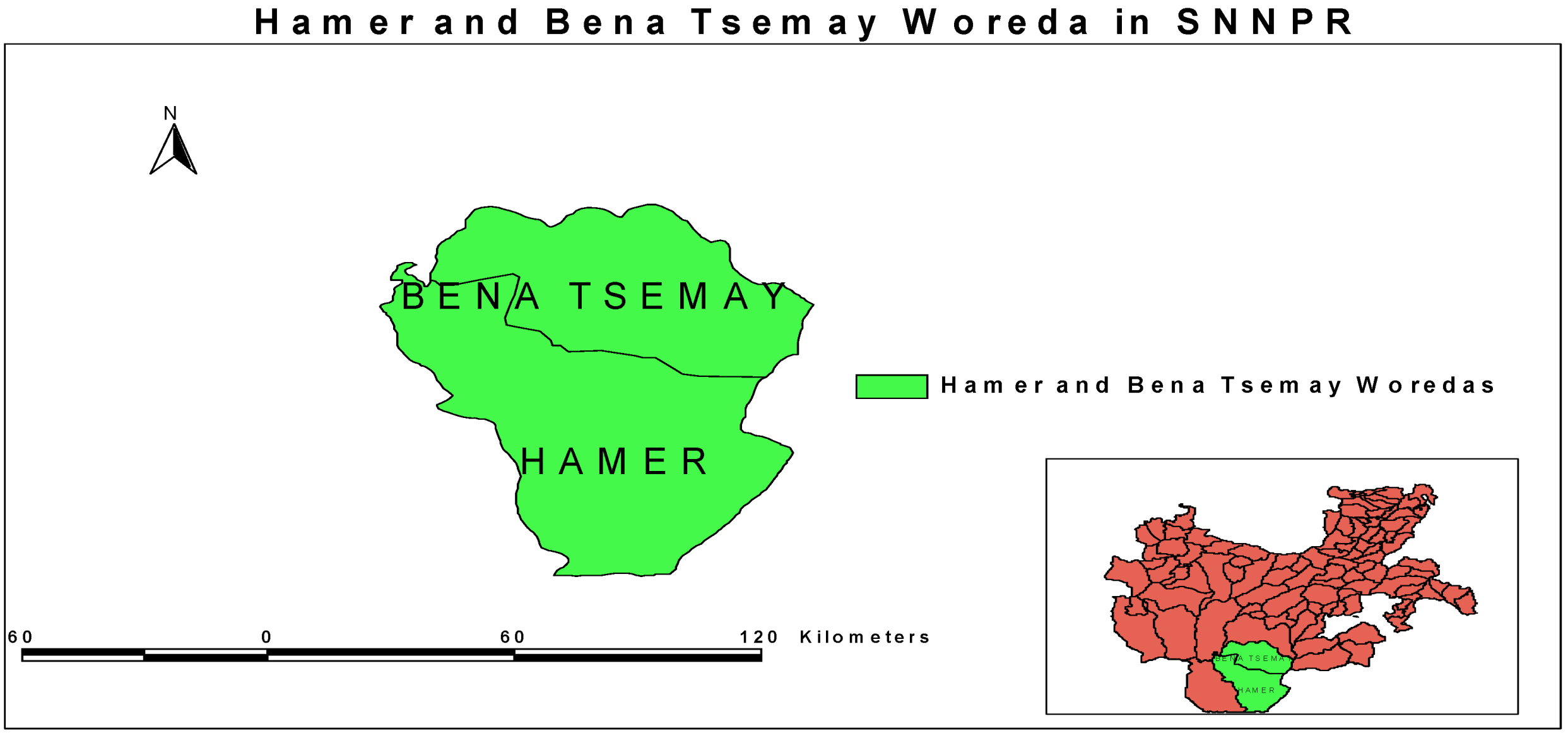

Pastoral and agro-pastoral communities are mainly found in four regions of Ethiopia: Afar, Somali, Oromiya, and the Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR). This study is conducted in the SNNPR, home to about 10% of the population [14]. The region is divided into 13 administrative zones [7]. Among these, South Omo is one of the most remote parts of Ethiopia. About 50% of the population is nomadic, migrating in search of water and grazing land for their animals, the mainstay of their livelihood [15]. South Omo covers an area of 22,000 square kilometers. It is regarded as a typical marginalized region, where infrastructure and social services are either very poor or non-existent in most areas. According to the SNNPRS livelihood profile [7], the study districts (Figure 1); Hamer and Bena-Tsemay, have an estimated total population of 62,006, of which 45% are female.

Figure 1.

Map of the study districts.

Figure 1.

Map of the study districts.

3.2. Sampling Technique

Sample households were selected through a multi-stage stratified sampling technique. In the first stage, the South Omo zone was purposively selected from among the pastoral and agro pastoral regions of Ethiopia due to its accessibility to Arba Minch University. In the second stage, two districts were purposively selected from the six (agro-) pastoral districts within South Omo, representing pastoral and agro-pastoral livelihoods. Finally, 3,876 households from four villages were stratified by well-being and sex of the household head, and 197 households were randomly selected using a lottery method. Household heads were selected as the unit of analysis since they are responsible for managing their family in all spheres. This unit of analysis is regularly used to capture the overall household well-being level [16]. It is also used as a proxy for assessing decision-making within a household.

3.3. Data Collection

3.3.1. Harvard Gender Analysis Framework

Primary data on household socio-economic characteristics, livestock and crop production, and gender relations; guided by the Harvard Gender Analysis Framework (HGAF); were collected from sample households through interviews. The Harvard analytical framework is adequate for household level data collection, and adapts well to agricultural and other rural production systems [17]. It aids to identify the types of gender differences and inequalities, such as how men and women have different access to and control over resources, carry out different social roles, and face different constraints and receive different benefits. Based on the HGAF, data is collected on men’s and women’s activities which are identified as either “reproductive”, “productive”, or “social” types, and how those activities reflect access to and control over income and resources. In addition, key informant interviews and focus group discussions (FGD) were conducted in each village. During the FGDs we observed that women are not permitted to speak in meetings where men are present. Consequently, a separate focus group discussion was conducted with women. In addition, secondary data on pastoral and agro-pastoral districts, and gender relations was gathered from the South Omo office of finance and economic development; secondary data on gender roles, inequality, and status in (agro-) pastoral communities was collected from published and unpublished sources.

3.4. Method of Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, percentage, t-test, and chi square test were used to analyze gender inequality with respect to socio-economic variables. In order to decide on the major correlates of well-being, multinomial logistic regression [18] was used. Data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics of Respondents

Gender inequality is a multidimensional term embracing economic, cultural, and social dimensions. This section discusses the key socio-economic characteristics of (agro-) pastoral households by the gender of the head of the household. As noted earlier, interviews were conducted with 197 households, 129 (65.5%) of which were headed by men and 68 (34.5%) which were headed by women.

4.1.1. Age at First Marriage

Early marriage is one of the most significant factors contributing to gender disparity in the study areas. As is shown in Table 1 the mean age at first marriage of male heads of households (MHHs) is higher by three years than that of female heads of households (FHHs), and the youngest age for both was 13. Early marriage is deemed to have taken place when the girl is under 18 years of age [5]. In the past, some girls were as young as five [19]. Three key reasons underpin the preference for early marriage and the eschewing of education for girls. The first is that it enables the parents to benefit from the bride gift that accompanies marriage. The second is that the sexual division of labor demands that females stay at home to serve their family until they marry. The third is fear that an educated girl will be less marriageable. As a result of women’s early age of marriage and men’s later age of marriage; husbands often die before their wives and consequently, many households are headed by women in the study areas.

Table 1.

Socio-economic characteristics of respondents.

| Gender of head | ||||||

| Continuous variables | Male | Female | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p value | |

| Marital age | 23.6 | 4.66 | 20.2 | 4.65 | 2.00 | 0.047 ** |

| Age of household head | 37.19 | 10.04 | 43.82 | 9.91 | −4.442 | 0.000 *** |

| Education of head in years | 1.56 | 1.59 | 1.0 | 1.44 | 2.41 | 0.017 ** |

| Family size in number | 6.05 | 2.76 | 5.6 | 2.14 | 1.27 | 0.207 |

| Family size in Adult Equivalent (AE) | 5.04 | 2.06 | 3.86 | 1.71 | 4.04 | 0.000 *** |

| Dependency ratio | 1.33 | 1.1 | 0.83 | 1.1 | 3.13 | 0.002 *** |

| Land size owned in hectares | 2.26 | 1.5 | 1.31 | 1.1 | 5.01 | 0.000 *** |

| Livestock holding in TLU | 32.83 | 67.8 | 24.52 | 38.5 | 0.93 | 0.352 |

***, ** significant at less than 1 and 5 percent respectively; SD, standard deviation.

4.1.2. Age of Household Head

Table 1 shows that the average age of male respondents was lower than females by eight years. This variation indicates that, on average, FHHs are older than MHHs since most of them survived their husbands. This is a general truth in other places in the world since women live longer than men in virtually all societies [20].

4.1.3. Education Level of Head

Generally speaking, pastoralists’ educational status was very low, even by rural standards. The majority of the sampled households were illiterate. The mean levels of education attained by male and female household heads were 1.56 and 1.0 years respectively. This indicates that the educational status of female household heads is lower than that of males by 64.1%. The study identified early marriage, lack of adequate schools in pastoral areas, and gender biased ideologies as barriers to girls’ education. Although there has been a continuous effort to promote girls’ education in the area; the problem is still deeply rooted.

4.1.4. Family Size

The average family size of MHHs slightly exceeds that of FHHs and is not statistically significant. Whereas, family size measured in Adult Equivalent (AE) (see Appendix Table 1 for conversion factors) exhibits a significant variation. The average family size is above the national average of 4.9/household. This may indicate that population density could be a problem in pastoral areas. Family size is also an important indicator of labor availability and consumption demand within a family.

4.1.5. Number of Dependents

Dependency ratio refers to the ratio of inactive family members (under 14 and over 64 years of age) to active family members (between the ages of 14 and 64). If the size is larger it implies there are large numbers of members who depend on others for consumption and other needs to be met. The average number of dependents for MHHs and FHHs was 1.33 and 0.83 respectively. This figure seems to be better for women headed households in terms of consumption shortfalls.

4.1.6. Land and Livestock Ownership

Grazing land is owned communally, while residence holdings are private property. Households in Hamer own the land under the homestead where women remain while men move with the livestock. In Bena-Tsemay, households own both farm and grazing land in addition to having access to the communal grazing lands. The average farmland holdings of MHHs is higher by almost one hectare than that of FHHs. Similarly, livestock holding in tropical livestock unit (see Appendix Table 2 for conversion factors) for male and female headed households were 32.8 and 24.5 respectively, which is not statistically significant.

4.1.7. Income and Expenditure Pattern by Sex

FHHs limited access to assets and other economic opportunities often results in lower productivity and income. Table 2 indicates the amount of income from all sources. The mean annual income earned by MHHs exceeds that of FHHs by 2390.9 birr per household; this indicates that earnings for FHHs was 40.1% of that of men. Crop and livestock incomes earned by MHHs are more than three and twofold, respectively, of FHHs. Similarly, income earned by MHHs from off-farm sectors exceeds that of FHHs by 347.8 birr annually. This demonstrates that not only do women headed households own less land and fewer livestock; they are generally unable to benefit from the principal output—the pastoralist economy.

Table 2.

Income and expenditure pattern by sex.

| Sex of household head | ||||||

| Male | Female | t /X2 | P | |||

| Income source | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Crop | 1904.55 | 3031.8 | 623.31 | 1244.8 | 4.14 | 0.000 *** |

| Livestock | 1698.07 | 2463.9 | 798.16 | 1094.2 | 3.49 | 0.001 *** |

| Off farm | 525.87 | 2305.7 | 178.09 | 397.7 | 1.23 | 0.219 |

| Total | 3990.5 | 4541.3 | 1599.6 | 1463.3 | 5.466 | 0.000 *** |

| Expenditure category | ||||||

| Food expenditure | 966.65 | 1094.75 | 750.44 | 682.97 | 1.44 | 0.15 |

| Value of own consumption | 8890.46 | 11750.03 | 3393.13 | 3834.46 | 4.85 | 0.000 *** |

| Non food expenditure | 655.64 | 833.18 | 151.88 | 162.83 | 6.631 | 0.000 *** |

***, significant at less than 1 percent respectively; SD, standard deviation.

Similar to the income distribution shown above, expenditure patterns indicate that MHHs have the lion’s share of both food and nonfood expenditures. The value of crop and livestock products consumed at home by MHHs is more than double that of FHHs. This demonstrates that the capacity of women to successfully feed their family is constrained.

4.2. Gender Roles in Pastoral Society

Gender roles refer to the rights, responsibilities, expectations, and relationships associated with men and women. The Focus Group Discussions identified three primary roles for (agro-) pastoral women. Their reproductive roles include: bearing and rearing children; processing, preparing, and serving food; caring for sick family members; collecting water and fire wood; milking and churning milk to make butter; grinding grain; and gathering wild foods. Women’s productive roles include; marketing of dairy products; herding, watering, and selling small stock; making handicrafts like wooden vessels and utensils; running small enterprises (coffee and local drinks); caring for young animals; taking animals to water; getting forage for calves, and weeding the crop farm. The social responsibilities of pastoral women include; maintenance of scarce resources, such as water and pasture, active participation in cultural events like weddings and funerals, as well as religious feasts.

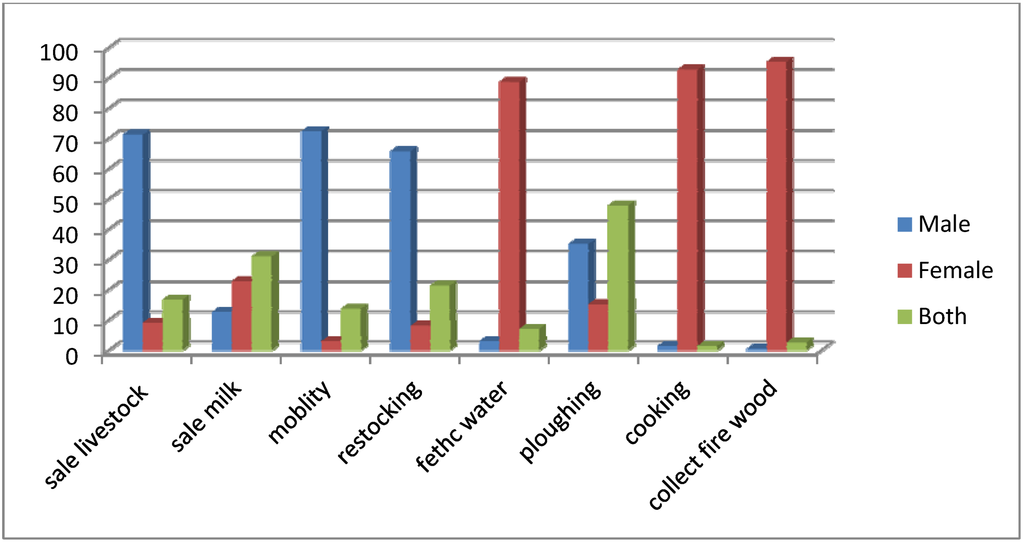

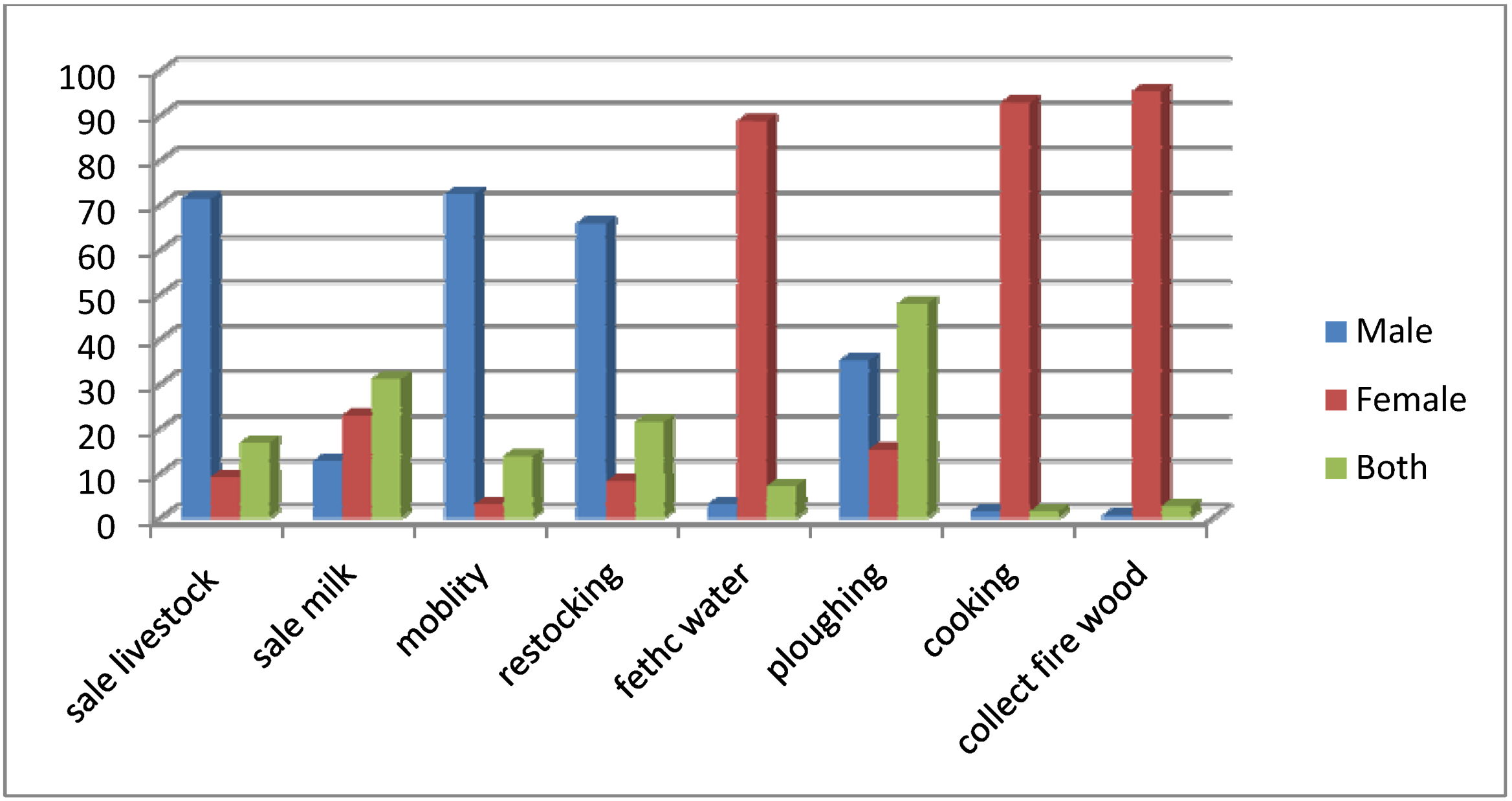

In order to quantify the time and effort invested by pastoral women to maintain their livelihoods. Table 3, Figure 2 present their daily routines and reproductive responsibilities.

Figure 2.

The role of men and women in livestock production.

Figure 2.

The role of men and women in livestock production.

Table 3.

Daily routines of pastoral women.

| Duration | Activities which women accomplish |

| 5:00–6:00 | Clean house, prepare coffee, breakfast and serve husband |

| 6:00–9:00 | Fetching water |

| 9:00–12:00 | Watering calves and weeding farmland (if any) |

| 12:00–16:00 | Collecting firewood and grasses |

| 16:00–18:00 | Grinding maize/sorghum |

| 18:00–22:00 | Cooking and serving dinner |

During FGDs, women were asked to describe and schedule their daily routines on the scale of 24 hour a day. Accordingly, Table 3 shows the average duration required to accomplish specific activities from different FGDs. We learned that pastoral women work longer than men. If a woman does not work hard, she is not a good woman. Thus, women work from early morning to late at night. In the morning they prepare the fire, cook breakfast and clean the house. They then collect water and firewood, grind maize/sorghum, which is laborious work, and look after children. As a result of these burdens, the daily routine of women takes more than 18 hours per day, women work 67% of the world’s working hours [20], whereas men work less than 12 hours a day, as confirmed from FGDs. In general, it is widely accepted that pastoralists, especially women, do not like to see a man doing women’s activities like fetching water and cooking food.

During the interviews, respondents were given a list of activities to rate as men’s, women’s, or joint decision-making responsibilities. The summary response in Figure 2 indicates that decision regarding sale of livestock, mobility, and restocking are the responsibilities of men. Whereas cooking, and water and firewood collection are the main tasks of women. The majority of women were more involved in livestock-related activities. They play a major role in grass collection and feeding, watering, milking, and processing milk by-products into food items. In most cases men supervise and command, women work and obey.

4.3. Well-Being Status by Sex of Head

A participatory approach was used to identify the indicators for ranking well-being. About 8–10 key informants were recruited through the Peasant Associations and included a minimum of two men, women, and youths. However, in some cases more than 10 people have attended the wealth ranking exercise. The key informants first identified local indicators of living well and determined the number of well-being strata; as ‘poor’, ‘average’ and ‘better off’. When asked to identify the characteristics of a household that lives well, key informants ranked ownership of livestock as the key indicator. Livestock serve as buffers against disasters, as longer-term prosperity, as capital for payments for wives, and as a measure of prestige. Next to livestock, land ownership and cultivation of crops were identified as a good sign of well-being. Another dimension of well-being was the ability to cope with shocks like drought and death of livestock, and being food self-sufficient. In the latter case, households that depend on relief food aid were considered poor.

As demonstrated in Table 4 15.75%, 38.58% and 45.1% of the total households are categorized as better off, average, and poor respectively. Comparison of well-being by gender indicated that out of the 31 better off households, only three are headed by females. This indicates that FHHs share only 9.7% of the wealth as measured by local indicators. This further indicates that households managed by women are more vulnerable to poverty than those headed by men. This again confirms that, in spite of women’s contribution to pastoral systems, their access and control over livestock is far below that of men.

Table 4.

Well-being status by gender of headship.

| Sex of head | Poor % | Average % | Better off % | Total % | X2 | P value |

| Male | 53.33 | 69.74 | 90.32 | 65.5 | 14.948 | 0.001 *** |

| Female | 46.67 | 30.26 | 9.68 | 34.5 |

***, significant at less than 1 percent.

4.4. Access to Services by Sex of Head

Access to credit, extension service, and veterinary services are key indicators of success in pastoral households. As shown in Table 5, access to credit, extension, and veterinary services are higher for MHHs than FHHs. In general, access to credit is limited in pastoral areas and the number of households that receive credit is very small. However, the proportion of women who benefited from credit is still somewhat lower than that of men. On the other hand, over half of FHHs accessed food aid, while the figure for MHHs is only 17.8%. The average months of food shortage for FHHs is also three times that of the MHHs. This indicates that the sex of the head of the household is an important variable in determining the ability of a household to achieve food security.

Table 5.

Access to social service and source of income by gender.

| Variables | Male (%) | Female (%) | X2/ /t | P value |

| Credit use | 28.7 | 25.0 | 0.03 | 0.582 |

| Food aid | 17.8 | 50.0 | 22.41 | 0.000 *** |

| Extension contacts | 61.9 | 38.1 | 4.046 | 0.044 ** |

| Veterinary services | 71.9 | 28.1 | 1.475 | 0.225 |

| Average months of food shortage | 1 | 3 | 22.41 | 0.000 *** |

**, *** significant at less than 5 and 1 % probability levels respectively.

4.5. Gender-Based Harmful Traditions

Physical and psychological harm to women is common in the study area. The major reasons are related to traditional beliefs about the status of women as it relates to marriage. This begins in the family and has been perpetuated across generations. Gender based harmful traditions like early marriage; Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), wife beating, and restricted access to education for girls are widespread practices in the study area.

During the focus group discussions with the women’s groups, two key reasons for the continuation of FGM emerged. The first one is due to the community’s value on ‘a circumcised girl behaves appropriately’. As a result mothers facilitate the circumcision of their daughters with a strong feeling of ‘a girl does not get married without being mutilated’. The belief is that a non-excised girl will run loose exhibiting highly inappropriate sexual behavior [4].

The concept that ‘women need to be beaten up to behave’ is viewed as the prerogative of her husband and is very strongly held to in the study areas. Local sayings like “women and donkeys need the stick”; “a woman is men’s servant” inspire husbands to show their power over their wives. The whipping of women is a ritual associated with the cattle-jumping ceremony, a rite of passage prior to marriage for all young men. During a man’s cattle jump in the cultural ceremony; sisters or other female relatives are whipped to express their love and devotion for the man. Scarring is considered a matter of pride. During the survey period we observed two ceremonies that included the whipping of women. We were shocked to see the backs of several women being wounded and bleeding. Even more distressing was their continued eagerness to ask for more beatings. The local authorities have been trying to stop the tradition of whipping women. However, elders are not willing to comply and condemn the threatened legal sanctions as an attempt to destroy their culture. There have been incidences where community members have clashed with the police while whippings were taking place. This challenge is compounded by tour guides and tourists. Many foreign tourists are attracted to the area specifically to view these traditional women beating practices. This increases the frequency of the practice which is often organized by local tour guides and hotels. Thus, a mechanism has to be devised to support the efforts of local authorities in tackling these harmful traditions.

4.6. Sex as Determinant of Well-Being Status

As indicated above, the measurement of well-being was mainly based on livestock and land ownership. However, well-being is also a function of other socio-economic factors. In order to identify the major socio-economic determinants of well-being in the study areas a multinomial logit model (MNL) was applied. The model test is significant at less than a one percent probability level, indicating that the variables included were relevant in distinguishing between the well-being categories. In regressing, MNL, the probability of being in the poor and average categories is compared to the probability of being better off since it is the reference category. The Nagelkerke’s pseudo R goodness of fit coefficient also supported this finding indicating that the model performed fairly well.

Table 6 shows the odds ratio among the independent variables entered in the model, (agro-) pastoral income, family size, and gender of head at p < 0.01, distance to market center at P < 0.05 were negatively correlated with the probability of being poor. This indicates that the likelihood of a household falling into the poor category decreases by a factor of 0.99 for a unit increase in (agro-) pastoral income, by a factor of 0.62 for an additional family size, and by a factor of 0.11 for MHHs. For average households, education and gender of head at p < 0.01; were significant. Education, gender, and family size have a negative correlation, which implies that they decrease the likelihood of households being in the average category, keeping other factors constant.

Table 6.

Multinomial regression of determinants of well-being status.

| Variable | Poor | Average | |||||

| B | Wald | Exp(B) | B | Wald | Exp(B) | ||

| Intercept | 9.255 | 24.939 | 3.744 | 4.838 | |||

| Age of head in years | −0.056 | 2.618 | 0.945 | 0.014 | 0.189 | 1.014 | |

| Education of head in years | 0.771 | 8.502 *** | 2.161 | 0.718 | 8.028 *** | 2.051 | |

| Dependency ratio | −0.0356 | 0.0169 | 0.9650 | 0.1367 | 0.3128 | 1.1465 | |

| Distance to market in km | −0.080 | 4.796 ** | 0.923 | −0.038 | 1.351 | 0.963 | |

| (agro-) pastoral income (ETB) | −0.001 | 14.983 *** | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.805 | 1.000 | |

| Off farm income (ETB) | 0.000 | 1.215 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.020 | 1.000 | |

| Family size in AE | −0.474 | 7.783 *** | 0.623 | −0.389 | 6.289 ** | 0.678 | |

| Gender of head (1, male, 0 female) | −2.234 | 7.549 *** | 0.107 | −1.438 | 3.235 * | 0.237 | |

| Extension contact (1, yes, 0, No) | −0.758 | 1.303 | 0.468 | −0.014 | 0.001 | 0.987 | |

| The reference category is: Better off. | |||||||

| −2 Log Likelihood | 299.2868 | ||||||

| Chi-Square | 92.61456 *** | ||||||

| Sample size | 197 | ||||||

*, **, *** significant at less than 10, 5 and 1% probability levels; ETB, Ethiopian Birr; km, kilo meter; AE, Adult Equivalent.

This finding indicates that the main socio economic factors affecting well-being in pastoral livelihoods are gender, family size, (agro-) pastoral income, distance to market, and education of head among other factors. The impact of level of education and market distance on the poor category is unexpected. The probable reasons may be due to the negligible role education, in general, plays in improving well-being in pastoral communities. Overall, educational attainment is very low and does not afford increased access to economic opportunities.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study confirm that women suffer from gender inequality by many standards. Women have lower educational status, fewer livestock, and less land due to discriminatory access and unfavorable attitudes. It is also evidenced that the probability of households falling into poverty is higher for households headed by females than males. The frustrating event is that many of the challenges and burdens on pastoral women will remain invisible and unnoticed, and are likely to be perpetuated from generation to generation through societal values and norms.

The major solution to achieving gender equality in pastoral society lies in the creation of awareness by women themselves, through training and education. Improving women’s lives requires capacity building, empowering practices, and participation in public decision making processes. This could be facilitated by organizing pastoral women’s associations and forums to build a collective voice. In addition, affirmative action, public awareness schemes, and support mechanisms should be devised and implemented to ensure equality and empowerment of pastoral women. Harmful traditional practices that affect the health and social status of women, such as FGM and early marriages, need to be targeted immediately. Above all the traditions of whipping women should be given priority and treated with caution as it may raise conflict between local authorities and communities. Interventions towards restricting the whipping of women, first and foremost, need to target and educate clan leaders. Then the community at large can be mobilized via clan leaders.

The structural invisibility of gender inequality in pastoral areas also demands educating the younger generation through school curriculums. In addition to ensuring completion of their education, transforming attitudes towards traditional gendered practices can have a significant inter-generational impact.

Finally we want to stress that future interventions need to recognize the cultural complexity within which these harmful traditional practices continue to exist.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Arba Minch University for financing and providing the necessary supports in conducting this research. In this regard, we are grateful to Kassa Tadele for his support and encouragement; Mr. Mihret Dananto for delineating the map of the study area. Our special thanks to Madine VanderPlaat for her valuable comments and time to improve the quality of this paper.

Appendix

Table 1.

Adult equivalent conversion.

| Age category | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

| <10 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| 10–13 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| >13 | 0.75 | 1.0 |

Source: [21].

Table 2.

Tropical livestock conversion.

| Calf | 0.25 |

| Cattle | 1.0 |

| Shoat | 0.39 |

| Poultry | 0.039 |

Source: [21].

References

- MoFED, Ethiopia: The Mellenium Development Goals (MDGs) Needs Assessment Synthesis Report; Development Planning and Research Department Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MoFED): Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2005 December.

- Elizabeth, T. Gender Role and Pastoralist Women’s Involvement in Income Generating Activities: The Case of Women Firewood Sellers in Shingle District, Somali Region Ethiopia. MSc Thesis, Van Hall Larenstein University, Waginingen, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mamo, G. ELMT “Good Practice Bibliography” Mainstreaming Gender Equality; Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (CARE) Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- PFE, Proposed Pastoral Development Policy Recommendations; Pastoralist Forum Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2002; Submitted to the Ministry of Federal Affairs.

- PFE, Promoting Gender Mainstreaming within Pastoral Programs and Organization; Pastoralist Forum Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2008; A generic guideline prepared by Pastoralist Forum Ethiopia in partnership with Oxfam Great Britain.

- Mohammed, M. A Comparative Study of Pastoralist Parliamentary Groups: Case Study on the Pastoral Affairs Standing Committee of Ethiopia; DFID, AU-IBAR: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- SNNPR (Southern Nations Nationalities Peoples Region), Livelihood Profile Regional Overview, Implemented by FEWS in collaboration with Disaster Prevention and Preparedness Commission (DPPC); The Government of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2005.

- Jensen, M.W. (Ed.) Indigenous affairs, Pastoralism, International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), Indigenous Affairs No 3–4/09, 2009. Available online: www.iwgia.org (accessed on 2 July 2011).

- UNCCD, Women pastoralists preserving traditional knowledge facing modern challenges. Secretariat of the (UNCCD) United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification: Bonn, Germany, 2007.

- de Villard, S.; de Pryck, D.J.; Suttie, D. Consequences of gender inequalities and policy options for gender equitable rural employment Workshop contributions- FAO-IFAD-ILO Workshop Rome part II, 2009. Available online: http://www.fao-ilo.org (accessed on 28 October 2011).

- Flintan, F.; Solomon, D.; Mohammed, A.; Zahra, H.; Yemane, B.; Honey, L. Study on Women`s Property Rights in Afar and Oromiya Regions, Ethiopia. 2008; Unpublished study for CARE Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Flintan, F.; Beth, C.; Shauna, L. Pastoral women’s thoughts on change: Voices from Ethiopia. In Paper presented on international conference on the future of pastoralism, Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, 21–23 March 2011; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgewel, A.; Getachew, M.; Flintan, F. Rangeland & Resource Management in Ethiopia, Gender & Pastoralism; SOS Sahel Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2007; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- CSA, Summary Statistics for Population Estimates; Central Statistical Authority of Ethiopia (CSA): Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2008.

- Opal Foundation. Project overview on South Omo, 2006. Available online: http://www.opal-foundation.com/article/south-omo/ (accessed on 8 September 2010).

- Dejene, A.; Don, P.; Girma, T. Gender, Irrigation and Livestock: Exploring the Nexus Policy Briefing; International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI): Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Overholt, C.M.; Anderson, K.C.; Austin, J. Gender Roles in Development Projects: Cases for Planners; Kumarian Press: West Hartford, CT, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Green, H.W. Econometric Analysis, 4th ed; University Macmillan Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, M.; Elizabeth, M.; Bizuayehu, F.; Demissie, G.; Anteneh, G. Social Assessment for the Education Sector of Ethiopia; Department for International Development: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dollar, D.; Gatt, R. Gender Inequality, Income, and Growth: Are Good Times Good for Women? In Working Paper Series, No. 1. Policy research report on gender and development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Storck, H.; Bezabih, E.; Berhanu, A.; Borowiccki; Shimeles, W. Farming System and Farm Management Practices of Smallholders in the Hararghe Highland; A base line survey (Farming systems and resource economics in the Tropics); Wissehschaftsverlag Vauk, Kiel: Kiel, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).