Abstract

In some Australian academic circles in the 1980s it was believed that, as the numbers of soldiers of the world wars declined over time, so would attendances at war remembrance ceremonies on Anzac Day and interest in war commemoration in general. Contrary to expectation, however, there has been a steady rise in eagerness for war memory in Australia over the past three decades manifest in media interest and increasing attendance at Anzac Day services. Rather than dying out, ‘Anzac’ is being reinvented for new generations. Emerging from this phenomenon has been a concomitant rise in war memorial and commemorative landscape building across Australia fuelled by government funding (mostly federal) and our relentless search for a national story. Many more memorial landscapes have been built in Western Australia over the past thirty years than at the end of either of the World Wars, a trend set to peak in 2014 with the Centenary of Anzac. This paper examines the origins and progress of this boom in memorial building in Western Australia and argues that these new memorial settings establish ‘circuits of memory’ which ultimately re-enchant and reinforce the Anzac renaissance.

1. Introduction

Over the past three decades there has been a steady rise in the numbers of war memorials built in Western Australia, which is the largest of the Australian states. Some 108 monumental memorials were built across the state from the end of the First World War until the conclusion of the Second World War. Between 1945 and 1970 there were 60 monumental memorials built and other forms of memorial such as buildings and gardens were also constructed. From 1980 to the present there have been well over 130 monumental war memorials built, with over 60 in the period after 2000. Green memorials such as gardens and honour avenues follow a similar although more gentle trajectory [1]. These figures suggest that war commemoration in Western Australia is booming and that memorials are being constructed at rates not seen since the end of the First World War.

At a local and personal level Australian war memorials hold memory of ancestors, relatives, friends and family members who have served and/or died in wars. Memorials have complex associations that work on national and political levels, often serving particular political agendas coupled with selective remembering and forgetting. As well, on local and personal levels, they serve as a focus for the trauma and grief of relatives and sometimes have a healing effect on the survivors of war [2]. Local and regional memorials, while overlaid with reference to the national politics of ‘Anzac’ and war remembrance, are usually more concerned with local remembrance—an aspect discussed more fully later in this paper. Anzac is Australia’s grand war narrative around which coalesces much national identity. As the prime focus of war remembrance ceremony, and because war has played a large part in our collective socialisation, memorials have been traditionally accorded a privileged place in the Australian landscape.

Driving through the urban areas and suburbs of Australian cities and country towns reveals many war memorials in parks, on roadsides or in front of public buildings advertising a community’s contribution to the defence of the country. Many of these were built during the first rush of memorial construction after the First World War as a material response to the sorrow, pride and grief felt by communities at the devastation of a generation of young people in mechanised warfare. A lesser number were built after the Second World War—often because the previous memorials sufficed. Memorials built after these wars were derived from established funerary architecture and also referenced Edwardian classicism and ancient symbolism, as these were languages best understood by the public. Obelisks, pillars, crosses, arches and urns had established meaning and these and other classical and ancient forms were employed to honour the heroic dead. Commemorative parks, gardens, avenues and utilitarian memorials such as buildings, drinking fountains and a plethora of other ‘useful’ items augmented these forms. The cult of Anzac—Australia’s national narrative (discussed later)—was essentially conservative and rejected modernism as a mode of artistic expression suitable to convey Anzac ideals.

Recently however, the memorial landscape is being supplemented by a multitude of new memorials—some which are abstract and experiential, drawing their meaning from modern forms. Communities can now chose a traditional or a non-traditional memorial although the latter can attract much local criticism founded on their apparent lack of association with the established meanings of Anzac.

The rise in the numbers of war memorials built is interesting as three decades ago it was felt that Anzac, as a potent shaper of Australian character and identity, was on the wane. This paper argues that the recent boom in memorial building in Australia in general and Western Australia in particular, is concurrent with an Anzac renaissance Australia is currently experiencing. The emergence of non-traditional memorials also marks a shift in the public acceptance of more experiential and narrative memorial designs that are aimed at new generations of Australians who have no direct experience of war.

This paper explores the drivers of the current boom in Anzac and war remembrance and endeavours to understand the effect this boom has had on the building of war memorials. It seeks to answer questions about why and how this phenomenon has been generated by discussing Anzac’s function in Australian society, its recent renaissance and its role in shaping attitudes towards war commemoration. Recent directions in war memorial design herald a new type of ‘therapeutic’ and interactive memorial which attempts to come to terms with the realities and trauma of war and its effects rather than simply advance the soldier as a hero and saviour of the nation. A number of contemporary non-traditional Western Australian memorials have been chosen to illustrate the effect of this trend. Ultimately, this paper shows that the recent rise in war memory is linked to the rise in commemoration and this in turn has spurred the increase in memorials built and the employment of a new memorial type. It is argued that the landscape has been increasingly ‘ritualised’ and this has had a particular effect on urban and regional settings. Through the circuits of memory set up by new memorial building and the re-enchanting of old memorials, the landscape has been ritualised and sacralised, reinforcing the place of Anzac as a legitimate national story and generator of national and local identities.

2. Anzac Memories

The origins of Anzac lie in the Gallipoli battles of the First World War when Australian and New Zealand forces stormed the Gallipoli terrain attacking to the north of Gabe Tepe on the Aegean coast.

The invasion aimed to cut short the Ottoman Empire’s involvement in the war as a German ally. Since seaborne attacks by the British and French navies on the Dardanelles (Straits of Çanakkale) defences had failed, land attacks to overrun the Gallipoli peninsula and force the surrender of Constantinople (Istanbul) were planned. The campaign was a massive and costly military failure that claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of British Empire, French and Ottoman troops including over 8,100 Australian and New Zealand troops with 18,000 wounded. However, in spite of shock and dismay at the carnage, stories of the behaviour and courage of Australian soldiers—bolstered by the derring-do descriptions of the war correspondents Charles Bean and Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett—combined to form a heroic narrative seen as nation forming. Shaped as an acronym of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, ‘Anzac’ became synonymous with the behaviour and social qualities to which Australians would aspire as it coalesced into a mythology that is a powerful force in the national imaginary. The hero of this mythology was the ‘digger’—at first a slang term for the Australian soldier that eventually encompassed the other armed services. To be called a ‘digger’ meant that you embodied the qualities of the Australian fighting soldier but also meant that you carried the full weight of obligation to live up to the myth. Remembrance and commemoration of ‘Anzac’ coalesced around Anzac Day each year on the 25th April, the anniversary of the landing at Gallipoli. The first Anzac Day observances were held in Australia in 1916, one year after the Gallipoli landings.

Gallipoli is also important for Turkey as a sacred place and has been so since 1915 [3,4]. The repulse of the naval assault on the Ottoman fortifications at the Straits of Çanakkale and the victory over the Allies on the peninsula is seen as a turning point in the formation of the Turkish Republic [3]. Important also was Mustafa Kemal’s role in the defeat of the allies on Gallipoli and his subsequent defining role as ‘Atatürk’, the first President of the Republic and the modernizer of Turkey. While this paper primarily pursues linkages to Australian commemoration and its influences in Western Australia, Gallipoli has important meaning to New Zealand as well as Turkey and it would be useful to briefly discuss New Zealand’s relationship to Anzac.

Australians tend to forget New Zealand’s involvement in the Anzac legend. Australia’s dominance of the story stems from the early development of Anzac Day [3] and despite official reminders from time to time conflict still arises over the role and place of New Zealand in Anzac. In 2011, for example, the relegation of the New Zealand contingent in the Anzac Day march in Perth to 131st place caused anger and claims of disrespect [5]. The link between the Gallipoli campaign and the national identity of both Australia and New Zealand is strong and connected to the perceived formation of both countries as independent nations—albeit in the context of the British Empire [6]. While there was a spirit of trans-Tasman friendship during the First World War years, this became strained as Australia began to monopolize the term and each country wanted to be identified separately [3]. From 1915, Anzac Day developed in New Zealand in concert with Australia although there was a more rapid coalescing of the form and meaning of the day in New Zealand [3]. In Australia it was difficult for six states with independent sovereign powers to agree. Queensland led the way for national acceptance of the day but it was some time before it was adopted by all the states and was encompassed in the federal organization [3].

Western Australia was the first Australian state to declare Anzac Day an official holiday in 1919. Returned service people were given a paid day off work and this concession was later expanded to the public service and others as a bank holiday. By 1929 there was a rough consensus among the Australian states on the meaning and form of Anzac Day, which is broadly the form it takes today [3]. This included a Dawn Service, a public march by returned service people, the military and civilian groups and an Anzac Day service around 11.00 am at a convenient and meaningful place. Not all places currently involve all these events some opting for only one or two. The form of service usually includes the basic elements of a prayer or reflection, wreath laying, the ode (traditionally “For the Fallen” by Laurence Binyon), the last post, one minutes silence and reveille or rouse. Many Australian ceremonies also employ a catafalque party as a symbolic guard. These elements have been at the core of Anzac services since the late 1920s and have not changed over this time although their meaning may have altered. For example, wreath laying is still an accepted form of tribute—an offering for the life of the dead and a comment on the fragility of life as the flowers fade. However, the personal meaning they held for close relations and other survivors of the dead has weakened and is lost to new generations who have a more distant perspective on the fallen.

In many Australian places, the 11.00 am service is followed by other events throughout the day. Notable is the evening ceremony held near sunset on Anzac Day at Tranby House in Maylands a suburb of Perth by the National Trust. Ceremonies prior to Anzac Day are also held on the evening before, such as the service at the Blackboy Hill War Memorial. This is followed by an all-night vigil at the memorial by local youth groups. The practice of the vigil and the guarding of a memorial at many memorials are, in part, to discourage vandalism and interference with the memorial before the Dawn Service.

In the late 1950s the appropriateness of Anzac Day as a national day was questioned and the drunken behaviour of ex-servicemen on the day was scrutinized. Disquiet was signalled by Ray Lawler’s play The One Day of the Year (performed in 1960) which dramatised the generational gap between the proud ex-service celebrants of Anzac Day and new generations who were contemptuous of the diggers revelry and suspicious of the elevation of war remembrance and its rituals. While heavily criticised at the time for being unpatriotic and disrespectful of wartime sacrifice, this successful play communicated alarm about the role of Anzac, seen by some as a racist, intolerant and militaristic civil religion [7]. Anzac was seen as an anachronistic pattern for citizenship that was out of step with new values being forged in the social revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s.

By the 1980s there was a general notion that the observance of Anzac Day and war commemoration was waning and, with the natural attrition of diggers numbers, Anzac commemoration would shrink and die. Indeed, this observation was, in part, a stimulus for Ken Inglis’s monumental study “Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape” begun in the 1980s and published in the late 1990s [8]. Inglis believed that a record of memorials and their mark upon the landscape should be preserved for posterity.

Contrary to expectations of that time, there has been a steady rise in commemorative activity in Australia since the 1980s and this rise in commemorative interest is reflected in the numbers of memorials (of all types) built in the state over the same period. This has been driven by the revival of Anzac as a national story and tradition that underpins notions of national identity where memorials form an intricate part of the rituals of war remembrance. The reasons for this resurgence are complex but a number of salient elements can be teased out and examined for their role in this Anzac renaissance. These include the ‘memory boom’, the search for a national identity, the reshaping of Anzac to suit new generations and the role of governments in promoting Anzac and war remembrance.

A significant generator of the Anzac renaissance is the so called ‘memory boom’. This is a complex global phenomenon originating in the late twentieth century and marked by growing public curiosity about memory and history [9,10,11]. It is manifest in the popularity of historical books, documentaries, genealogical television shows and websites dedicated to tracing ancestors. However, other manifestations such as the Shoah, Holocaust museums and the debates sparked by Holocaust remembrance have engendered reflection of the “notion of memory” and on “what kinds of memories are elicited by other commemorative projects” [10]. In this context, war memory emerges as a proliferation of “public interest in the cultural and political extent of war memory” noticeable in media of all kinds [12]. Allied with these developments is ‘post-memory’ a concept which attempts to explain the transference of the trauma of war and its effects across generations [13,14,15]. Critiques of the memory boom concept asserts that much work on memory has been “derivative and tautological” claiming that under the weight of memory studies “memory fatigue” is imminent [15]. However such criticisms are directed at the research community and do not take into account the popular manifestations of the memory boom.

Interest in war memory is apparent in the numbers of anniversaries of wars and war events that provide opportunities to reiterate mythic national narratives such as Anzac. Remembrance projects such as the ninetieth anniversary of the Battle of the Somme in Britain in 2006 and Australia Remembers 1945–1995 in 1995 to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War Two in Australia are examples of reimagining national identities forged in war.

Here, memory can be seen as interlocking with remembrance and commemoration. I do not believe that a definitive meaning or knowing of what memory was and is will be useful to this paper. As Tanja Luckins observes “there was no ridged configuration of memory—indeed it was sometimes located in the cultural forms themselves” [16]. In her research, memory across the generations was “ambiguous and conflicting” rendering any single definition difficult [16]. It must also be said that individual memory should not be confused with the memory of societies [17]. The concept of collective (or social) memory is a difficult subject and its meaning, opposed to individual memory, is contested when considering objects of public memory such as a war memorial. Collective memory is most aptly described by Wertsch as a “term in search of a meaning” [18]. Nevertheless, cognisant of the difficulty, I propose that for the purposes of this paper, collective memory as applied to a war memorial could be usefully described as “the representation of the past, both that shared by a group and that which is collectively commemorated, that enacts and gives substance to the group’s identity, its present conditions and its vision for the future” [19]. In this context, Anzac as a vehicle for national memory is framed by the identity forming aspects of the mythology itself, its political and social uses and the resulting material culture.

Riding the memory boom, Anzac has been successful in reviving its influence. Donaldson and Lake (2010) believe that the Returned and Services League (RSL), a preeminent veterans organisation, was instrumental in the failing fortunes of Anzac Day through its conservative and exclusive attitudes. It was rescued in the 1990s by the federal government, which effectively displaced the RSL as purveyors of the national mythology. Through the auspices of the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Australian War Memorial the federal government has “assumed national custodianship of the spirit of Anzac” [7]. Certainly the RSL’s conservative and often racist attitudes were seen as out of step with changes in society. However, it would be wrong to say that all RSL members were of this ilk. The great strength of the RSL was (and still is) its diversity [6]. Sub branches were effectively left to run their affairs as they saw fit and there were many views—not all in accord.

The renaissance of Anzac Day can also be attributed to a growth in the politics of patriotism, which started in the 1980s. As the 1988 Australian bicentennial approached, sponsorship of Australia Day increased as an alternative to the failing Anzac Day. Australia Day (originally known as Foundation Day) celebrated the establishment of the first settlement in New South Wales in 1788. However, attempts to elevate Australia Day were eventually abandoned because of its inability to include the celebration of all Australians. Aboriginal protest that Australia Day symbolized their dispossession virtually derailed the scheme and Anzac Day was once again seen as a viable alternative as a national day [20]. Anzac Day also suited Aboriginals who strove to be included. Many indigenous people had fought in Australia’s wars and had been excluded from repatriation and ex-service benefits. It was not until 2001 that Aboriginals marched in a group on Anzac Day. Curiously, despite their support of the White Australia Policy, the RSL generally championed Aboriginal repatriation and their inclusion in RSL affairs—although not all branches held these views [6]. Other groups such as Vietnam veterans were denied membership to some RSL sub branches when they returned from overseas service in the 1960s.

The ‘new nationalism’ or ‘politics of patriotism’ (mentioned earlier) has also contributed to the Anzac renaissance [21]. New nationalism is symptomatic of Australia trying to find its place in the world as an independent nation but its manifestation in Australia Day as well as Anzac Day is increasingly being manipulated and, for some, risks becoming ostentatious and jingoistic [22].

Celebrations across Australia in 2014–2018 are intended to commemorate the centenary of Australia’s involvement in the First World War. The National Commission on the Commemoration of the ANZAC Centenary was formed by the federal government in 2010 to identify activities for a national commemorative program for 2014 to 2018. Groups and organisations across Australia were asked to submit proposals for possible recognition and funding and the process to find commemorative activities is ongoing.

3. Anzac Landscapes

Since the Renaissance, memory has been associated with the idea that material objects can act as “analogues of human memory”. Memories can be assigned to material objects and, by virtue of permanence, capture and stand for that memory over generations [23]. The concept of a war memorial as a prompt or reminder arises from these notions.

As Ken Inglis observes, war memorials in Australia are regarded as ‘sacred places’ and are accorded special respect as places that honour the sacrifice of service people in war [8]. As cultural objects they also symbolize other aspects of war experience such as memory, loss, grief, dissension and anger. While part of the material culture of war memory, memorials are inextricably intertwined with Anzac and with its recent rehabilitation. Crowds at Anzac Day and other war ceremonies continue to grow. In Western Australia alone, an estimated 40,000 people packed the space around the State War Memorial for the Dawn Service ceremony at 6am on Anzac Day in 2011 [24]. Like Anzac, memorial forms are changing. Traditional forms of memorial are giving way to more abstract and interactive memorial designs.

After the First World War the ‘tyranny of Anzac’ ensured a conservative stance in the design of memorials—enforced by the RSL and others with a stake in memorial building. For the RSL, only classical and ancient design could convey the nobility of the digger who could be aligned with ancient warriors through ancient symbolism. The RSL was anti modernist, critical of abstract art and scathing of war artists such as Paul Nash who depicted the barren landscapes of warfare as geometrical and wrecked [6]. Until well after the Second World War, Anzac remained essentially conservative in art and in war memorial design. However, “an emergent spatial turn” in war memorial design occurred with the Vietnam War Memorial in the Washington Mall, Washington designed by the young architectural student Maya Lin (see Figure 1) [25]. Built in 1988 the memorial consisted of a deep vee cut into the landscape which was lined with black granite onto which the names of the dead from the Vietnam War were inscribed. Lin did not want an “unchanging monument” but a “moving composition” which was a quiet space “for personal reflection and private reckoning” [26]. It was heavily criticised as a monument because it did not celebrate the soldier as hero and eventually a flagpole and statues were placed near to appease traditionalist sympathies. This memorial was pivotal as it showed what was possible in war memorial design and it was at the forefront of the acceptance of a new breed of memorial that was often modernist, narrative and “therapeutic” [25]. The therapeutic memorial tends to eschew the view of the soldier as hero and explores the idea that war traumatises participants and their survivors. These new memorials are evident in societies that are more open to look beyond national agendas for the meaning of death in war, although not all communities agree to build them. Therapeutic monuments such as the Vietnam Memorial in Washington “existed not to glorify the nation but to help its suffering soldiers heal” [25]. Research has shown that the memorial has had beneficial effects on Vietnam veteran visitors [2]. This effect can also be extended to survivors such as relatives and family members. The new design direction also favours memorials that are narrative—they often tell stories, in abstract or direct ways, about war and its effects. The rise of a ‘narrative’ memorial is concurrent with the memory boom and what has been termed the ‘narrative turn’ [15]. Here art—as part of post modernism (itself a ‘narrative turn’)—“witnessed an explosion of interest in narrative practices” [27]. This is not to say that traditional memorials were not narrative but that they now often tell more complex stories about war experience and its aftermath. Examples of non-traditional narrative memorials in Western Australia are the HMAS Sydney II Memorial (2003), the Mandurah War Memorial (2005) and the Ballajura War Memorial (2006).

Figure 1.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington Mall Washington USA (courtesy E Karol).

Figure 1.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington Mall Washington USA (courtesy E Karol).

The HMAS Sydney II Memorial is dedicated to the memory of the 645 lives lost in the sinking of the HMAS Sydney II on the 19th November 1941 by the German auxiliary cruiser HSK Kormoran in a mutually destructive battle off the coast of Western Australia near Geraldton north of Perth (Figure 2). There are many accounts of the Sydney’s engagement with the Kormoran, the result of a massive program of research and supposition over the years since 1941. At the time the memorial was constructed in Geraldton, the resting place of neither ship was known and the memorial had poignancy for family survivors. The memorial is a very large landscape containing complex symbolism concerning the souls of the sailors transposed into seagulls, the uncertain fate of the sailors and the suffering of those who waited in vain for the ship to return. Containing a number of large structural elements, the memorial space includes a ‘dome of souls’ covered with 645 stainless steel seagulls intending to represent the lost sailors. From the dome hangs an ‘eternal flame’. A ‘stele’ or marker in the shape of a full scale replica of the bow of the Sydney resides in one corner and a large curved highly polished black granite ‘wall of remembrance’ with etched names of the sailors and photos of the ship partially encircles the space. A life sized bronze statue of a woman looking out to sea echoes the uncertainty and loss caused by the sinking.

On a windswept and exposed hill overlooking the City of Geraldton the memorial provides a spiritual and healing setting for some. For example, Gail Kemp, niece of Able Seaman Benjamin Baker lost on the ship, watched the emotional upset of her mother each Anzac Day and says that the Sydney memorial in Geraldton provides a place of pilgrimage. She describes the memorial as a ‘beautiful place’ for relatives to grieve. For her family, it was a relief that the Sydney was found [28].

Figure 2.

HMAS Sydney II Memorial, Geraldton Western Australia (source author).

Figure 2.

HMAS Sydney II Memorial, Geraldton Western Australia (source author).

The largely abstract Mandurah War Memorial (Figure 3), which is in a small coastal city south of Perth, is constructed on a lonely field situated on an estuary. This is one of the most abstract and experiential memorials in Western Australia. The memorial consists of rows of white concrete pillars rising in an estuary to a maximum height at the ceremonial space and then gradually falling across the landscape to the waters of a canal on the other side of the field. The rows of pillars symbolically depict the rise and fall of battle and are aligned to the rising sun on Anzac Day. The Anzac Day Dawn Service at this place is an emotional and dramatic event as the rising sun casts long blue shadows across the memorial and lights up the naval catafalque party surrounding a small black obelisk in the centre of the memorial. Water, which cascades between the pillars to the estuary, symbolizes the tears of survivors. Fragments of an anonymous poem narrating the horrific war experience and death of an Australian soldier are etched into the columns. Architecturally arranged rows of New Zealand Christmas trees (pohutukawa) recognize the New Zealand involvement in Anzac and box shaped topiary rosemary bushes signify memory. Rosemary is, historically, a favourite for Australian war memorial gardens. At the end of each Dawn Service, participants are invited to move through and experience the memorial from within its structure—an activity not generally available in a traditional memorial.

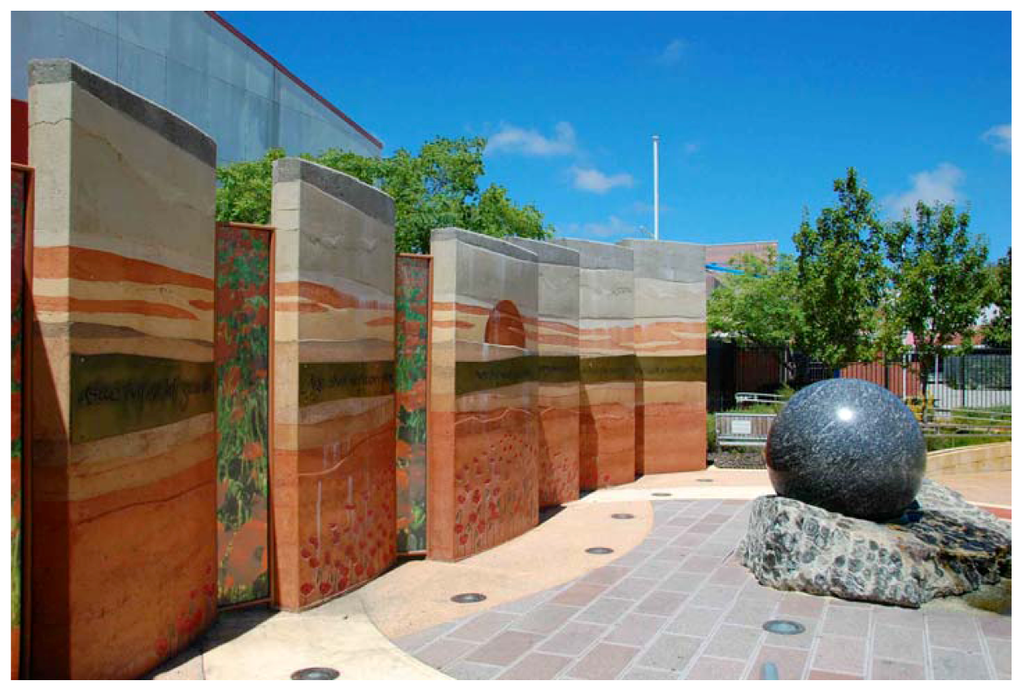

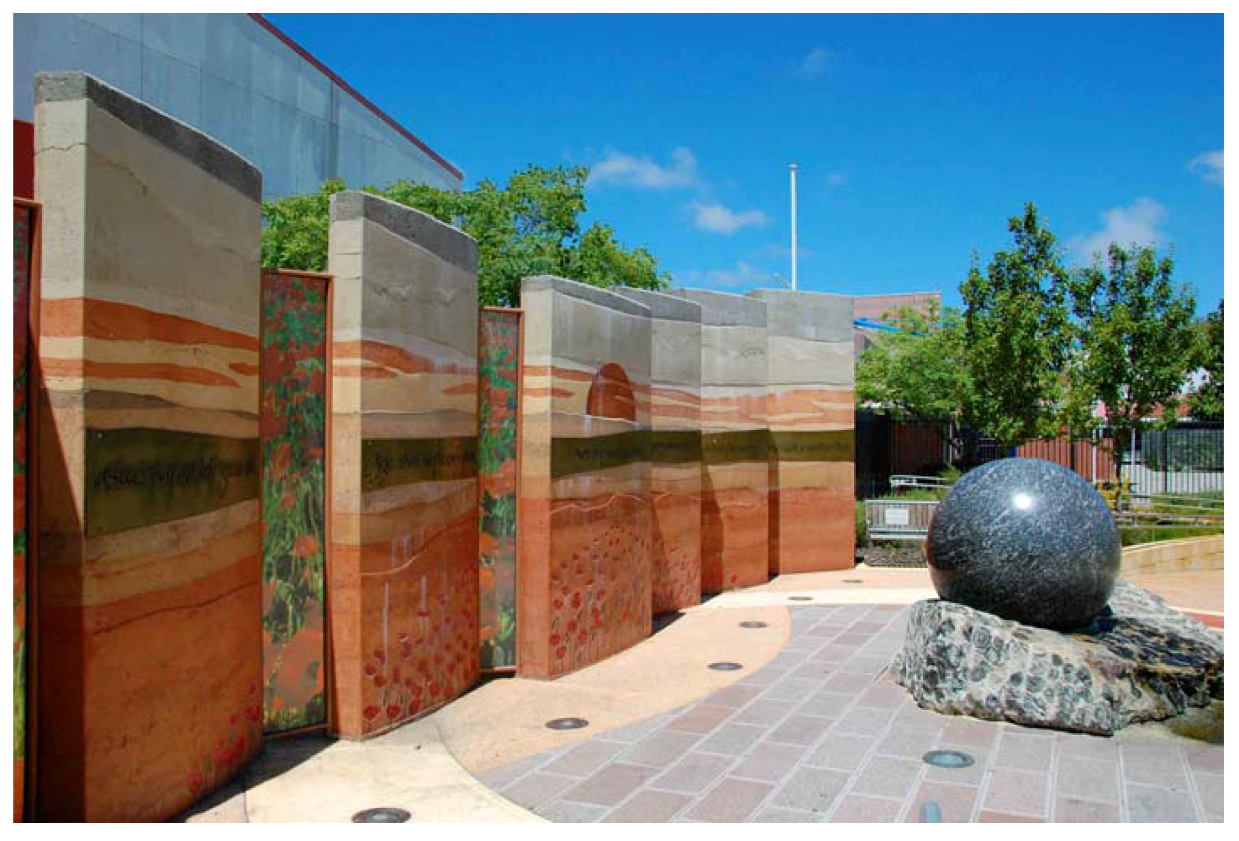

The Ballajura War memorial (Figure 4) is in a Perth suburb at the entrance to the Ballajura Community College. Framed by a sizeable circular ‘peace park’ containing olive trees and a Gallipoli pine, the memorial consists of large coloured rammed earth (pisé de terre) panels depicting a stylized Australian landscape and rising sun with perspex panels holding images of red poppies between each earthen panel. Symbolising ‘peace in the world’ a large stone ball of Western Australian granite ‘floats’ in water in a granite receptacle in front of the panels. Across the panels in brass are the words to Laurence Binyon’s ‘Ode to the Fallen’. In Commonwealth countries red poppies were adopted as symbols of sacrifice as they often grew over the graves of soldiers in Europe, also prompting McCrea’s famous poem ‘In Flanders Fields’. This is a narrative memorial where an iconic Western Australian landscape has been superimposed with Flanders poppies. The pictorial landscape—physically comprised of earth from various parts of Western Australia—references the open vast landscape of the state from which the fallen have come. The fallen are symbolically represented by the poppies and are literally engraved into the landscape emphasizing the connections of this landscape to those in which the dead lie. Designed for personal reflection “in remembrance of love, honour, remembrance and hope” and “loss incurred through war, service or personal tragedy” it is very much a community memorial with links to the service and sacrifice of former community members from all wars and recent peacekeeping operations [29].

Figure 3.

Mandurah War Memorial Western Australia (source author).

Figure 3.

Mandurah War Memorial Western Australia (source author).

Figure 4.

Ballajura War Memorial Perth Western Australia (source author).

Figure 4.

Ballajura War Memorial Perth Western Australia (source author).

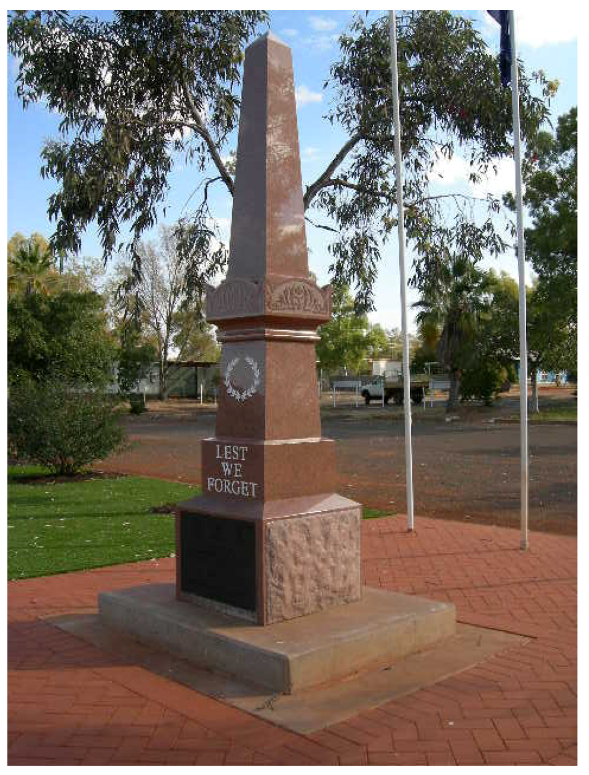

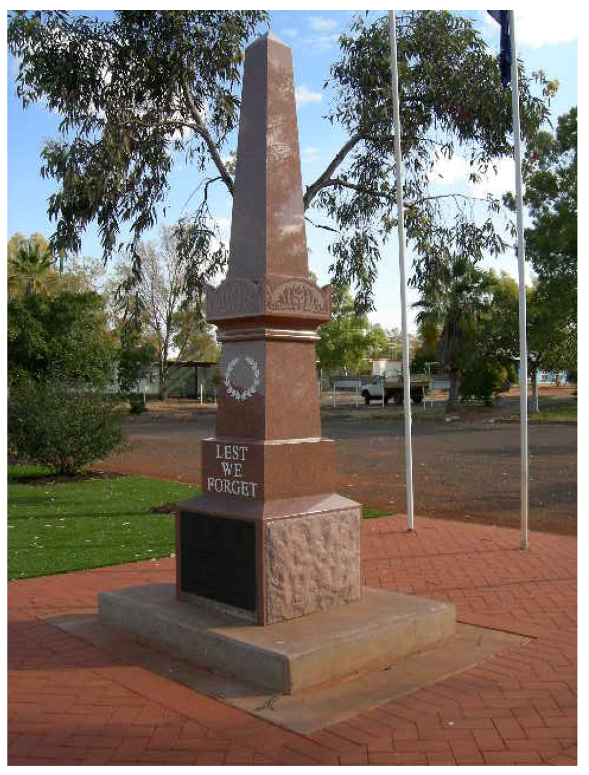

Not all memorials are narrative or therapeutic and many Western Australian communities still prefer traditional memorials. Sometimes straightforward forms or rocks are employed simply because there is not the funding available for more complex memorials. An example of this is the Laverton War Memorial built in 2005 that mimics many classical obelisks built in the 1920s (Figure 5). However the simple 80 Mile Beach War Memorial (near Broome) built in a caravan park (Figure 6) is a therapeutic memorial to those that constructed it. It is timber memorial in the shape of a Long Tan Cross and it is the work of Vietnam veterans who stay at the caravan park annually. Attracting over 300 people to Anzac Day ceremonies at this very remote place, the memorial has a particular commemorative meaning for its constructors.

Figure 5.

Laverton War Memorial Western Australia (courtesy Jacqui Sherriff).

Figure 5.

Laverton War Memorial Western Australia (courtesy Jacqui Sherriff).

Figure 6.

80 Mile Beach War Memorial Western Australia (courtesy of Ray Miles).

Figure 6.

80 Mile Beach War Memorial Western Australia (courtesy of Ray Miles).

These memorials echo the ‘spatial’ and ‘narrative’ turns that emerged in the Washington Vietnam Veterans Memorial and elsewhere in the latter half of the twentieth century. None are traditionally heroic in the conventional sense and most are narrative, reflective and– particularly the HMAS Sydney II memorial—are meant to heal. The construction of these new types of memorial not only signals an emergent requirement for more experiential and narrative memorials but are also allied to changes in Anzac itself and its conservatism. Changes can be detected in the Anzac Day marches. Where once only the returned Australian soldier was permitted to march, recently marches have included former enemies such as Turks and other groups representing the Vietnamese community and (belatedly) Aboriginal service people. Turkish RSL sub-branches in Western Australia and Victoria have formed in recent years. While reasons for this are partly political and due to close ties between Australia and Turkey, it also indicates that the exclusiveness and prejudices of the ideology are being slowly broken down.

Also, as the majority of veterans from the First and Second World Wars and subsequent wars perish, direct memory and experience of these conflicts diminishes so that that the hold of memory and history represented by these people is loosened. Current generations are free to interpret Anzac in the light of their own experience and what they perceive to be the values that Australia should embrace [20,30]. Likewise the link to the funerary aspects of memorial design (represented by classical design forms) and the memorial as a substitute tomb is also weakened. Until 1965 soldiers’ bodies were buried in overseas cemeteries and local war memorials regarded as ‘empty tombs’. As soldiers bodies are now returned to Australia, memorial design is now free to take routes away from funerary references, although in the absence of direct war experience and memory they may need to have a more didactic role.

Memorials are usually funded by public and private subscription although the Department of Veterans Affairs and state governments may contribute or release funds for new memorials and the maintenance of the old. For example in 2006 the federal Department of Veterans Affairs provided funding for construction of war memorials in towns without an existing memorial. The Department currently offers funding for war memorials through its ‘Saluting Their Service’ program, which also produces ‘curriculum materials’ on Anzac for schools and hosts an Anzac essay prize. Some states such as Victoria offer substantial funding for the upgrading or restoration of existing memorials. Lotterywest, a statutory authority in Western Australia, provides large amounts of funding for commemorative purposes and a prominent insurance company, SGIO, may provide funding for war memorial restoration. By promoting war remembrance through some of its departments and the Australian War Memorial, the federal government has been accused in some academic circles of overstating war commemoration and ‘militarising’ Australian history [31].

The effect of these new and established memorials on the landscape is interesting. They have properties that draw them into a network of spaces that ritualise the landscape.

4. Circuits of Memory

Nuala Johnson argues that the places that memorials occupy are important as an intrinsic part of their meaning to national identity. These sites of memory are not arbitrary “but are consciously situated to connect or compete with existing nodes of collective memory” [32]. As sites of memory, war memorials are located within “circuits of memory” and are “points of political and ideological convergence” [33]. Johnson questions Pierre Nora’s notion that the meaning of memorials is ‘intrinsic’ and argues that location is an important factor is defining a memorial’s meaning. The same memorial elsewhere does not absorb the same local politics and “geopolitical discourses”. Location is not arbitrary for other reasons as well. A memorial is dependent on memory, which fixes its position so that it is ‘consciously’ situated. Here, a memorial can be an “ideologically charged site” that Brian Osborne says of memorial places transformed by public rituals—power is ‘performed’ there [34]. In this context memorials connect with the national ideology of Anzac and its ritual celebrations. War memorials are interconnected through their associations with Anzac and commemorative practices and are linked though a common reference to the overarching national ideology and civil religion that Anzac provides. They provide a space in which to conduct ceremonies and rituals associated with honouring the dead and reinforce national values of citizenship. Through the retelling of Anzac mythology and through ritual actions each memorial space is re-enchanted as a sacred space. For example, most Anzac Day services contain common elements such as wreath laying, where participants approach the memorial with reverence and place a wreath against the memorial or other object as a symbolic act honouring the dead.

These and other ritual actions in an Anzac ceremony invoke a state of ‘communitas’ where there is a temporary (and sometimes more permanent) binding of people through the liminality of ritual and ceremony [35]. Turner and Turner conceive this bonding as a luminal state amongst a group of people to be ‘communitas’ [35]. Liminality refers to transformations in the body of people participating in ritual practice. They move from a present state to another that involves changes in moods, feelings and emotions that suspends the normal order of things, facilitating cooperative participation in a ritual [35,36]. Places that are the focus for community ritual and ceremony must support and evoke communitas amongst participants and visitors to be successful [37]. Coleman and Eade question the existence of communitas or a luminal experience arguing that the paradigm is romanticist and a “theoretical cul-de-sac” [38]. Margry shares this view but concedes that in pilgrimage situations there are “important group connections and forms of sociability” [39]. Even so this paper takes the view that communitas or other social bonding process is present during an Anzac ceremony. In Tiwari’s view, ceremonies write themselves onto and into a space charging it with special meaning. Ritual strengthens the relationship between the body and the space where the body plays a role in constructing it [36]. In this context the ritualised bodies of the participants in a ceremony occupy and write ‘socio-cultural’ aspects into the ceremonial space that can be read as a text or a narrative [36]. The narrative here is that of Anzac and its attendant ideology. Places such as war memorials emerge as spaces that facilitate these effects and are drawn together into a common circuit of memory and focus of ideology and political agenda linked to national identity.

Yet there are other processes at work that may erode the national aspect of war commemoration and overlay the meaning of local war memorials. The notion of ‘nation’ as vehicle for a unified and collective identity is unstable and communities will often appropriate the material forms of national commemoration—but mould this to fit local purposes [40,41]. This is manifest in individual local traditions in Anzac ceremonies such as releasing doves, firing rifles, singing, poetry and other individualising practices. There is often a ceremonial focus on locals who served and died as a dominant part of the nationally collective ‘fallen’.

Bauman argues that “[S]tate endorsed nationhood is increasingly contested as the principal frame of cultural identity, by smaller scale allegiances” such as communities [42]. But in order to gain their identities, communities must invent their own traditions that drown out competition and “contest the competitors’ view of what in the past was united and what was disparate, and assign prime importance to what competitors would rather marginalize or better still make forgotten”. In Bauman’s view, the identities that nation-states forge are “too nebulous [and] immaterial” and prey to contest from its communities [42]. In this circumstance, local memorials loosen the national grip on Anzac, mould it to local concerns and establish complex sites of contest that engage in a slow “uneven erosion” of the national [42]. In these mnemonic spaces the grand national narrative of Anzac is mediated through local interests feeding the continuing re-invention and development of Anzac.

What this means is that memorials are places of contest between the pervasive ideology of Anzac and links to national identity, and the local will to mediate the ideology to better fit the indigenous identity and politics. In a sense, this means that the ideology becomes more powerful as it is bent to local purposes ensuring its constant reinvigoration.

5. Conclusions

This paper reveals that the cumulative effect of the many war memorials built across the urban and regional localities of Western Australia is to form a web of places that ritualise and sacralise the landscape. War memorials become part of a network of interlinked sites that reinforce the social and political narratives of Anzac. Furthermore, changes in Anzac are allied to changes in war memorial design.

As previously discussed, the past thirty years has seen an increase in the number of war memorial spaces constructed in Western Australia. Hand in glove with the so-called memory boom, the attendant increase in interest in war memory has also been driven by new nationalism and the politics of patriotism. As Anzac is changing to suit new generations without a direct experience of war, a more didactic aspect is forced into its rituals and ceremonies that are no less powerful vehicles for national and regional identity. Memorial design follows this trend to cater to new generations who demand more overtly narrative and interactive memorials than can be delivered by traditional memorials. New memorial sites also herald a more liberal and inclusive view of Anzac where the design of memorials may represent a loosening of the past racist and exclusive attitudes that were often promulgated by Anzac and its conservatism. Instances of this loosening can be found in the growing number of memorials dedicated to Aboriginal war service and the inclusion of Turkish marchers in Anzac Day parades. Under these changing conditions these sites may also provide a more honest and meaningful conversation between the participant and the memorial. Even so, recent traditionally designed memorials may not mean that their ritual meaning is necessarily linked to a conservative Anzac ideology.

As Australia takes a more independent position in the world the question of identity, reinforced by important national narratives, becomes crucial. While the search for a national story has been a feature of Australian culture since the nineteenth century (and eventually coalesced around the events at Gallipoli) Australians are still searching for a national narrative that distinguishes them and describes their national characteristics. Anzac provides a ready, overarching narrative that is malleable enough to cater for present generations.

However, the rise of Anzac does not necessarily signal a backward gaze to the pride of a militaristic past or for nostalgia for past glory—although there is always the danger that this might happen. Anzac is an established canvas upon which new generations can paint their own identities using the ideals of Anzac. Australia is not alone in aspiring to these ideals—most nations proclaim the same values. But Australia has its own understanding of these values as they were created in a military defeat and human tragedy from which the trauma still resounds.

As described above, local memorials are in tension with national narratives as communities move to appropriate these narratives for their own, although it may be argued that such localised effect and appropriation makes the narrative more relevant and powerful as it is bent to local concerns and issues. Localisation of the national narrative allows a more meaningful conversation between the rituals of Anzac and the memorial space that supports it.

War memorials are the material effect of these issues, forming “points of political and ideological convergence”. Each memorial is drawn into a web of memory imposed on the urban and regional landscapes that—for good or ill—legitimatises Anzac as a national ideology. The consequence of this web of memory is that it ‘amplifies’ the effect of Anzac and is, at once, both effect and a generator of war memory.

Australia’s appetite for memorialisation means that there is a growing investment in the Anzac ideology and the will to materialise this into the urban and regional landscapes in ways that reflect a re-imagining of the national mythology of Anzac.

References

- Stephens, J.; Seal, G.; Witcomb, A. Remembering the Wars: Community significance of Western Australian War memorials; ARC Linkage Project LP0668375; Curtin University: Western Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, N.; Cole, F.; Weidemann, S. The War Memorial as Healing Environment: The Psychological Effect of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on Vietnam War Combat Veterans' Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 351–375. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, G. Anzac Day Meanings and Memories: New Zealand, Australian and Turkish Perspectives on a Day of Commemoration in the Twentieth Century; University of Otago: Dunedin, New Zealand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fewster, K.; Başarin, V.; Başarin, H.H. Gallipoli:The Turkish Story; Allen and Unwin: Crows Nest NSW, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bovill, K. Give NZ respect. The West Australian 2011, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Garton, S. The Cost of War: Australians Return; Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, C.; Lake, M. Whatever happened to the anti war movement? In What's Wrong With Anzac? The Militarization of Australian History; Lake, M., Reynolds, H., Eds.; University of New South Wales Press: Sydney, Australia, 2010; pp. 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, K.S. Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape; Melbourne University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Todman, D. The Ninetieth Anniversary of the Battle of the Somme. In War Memory and Popular Culture; Keren, M., Herwig, H., Eds.; McFarlan and Company: Jefferson, NC, USA, 2009; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, J. The Memory Boom in Contemporary Historical Studies. Raritan 2001, 21, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman, S. Crisis of Memory and the Second World War; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ashplant, T.G.; Dawson, G.; Roper, M. The Politics of War Memory and Commemoration: Contexts, Structures and Dynamics. In The Politics of Memory: Commemorating War; Ashplant, T.G., Dawson, G., Roper, M., Eds.; Transaction: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 3–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, M. Surviving images: Holocaust Photographs and the Work of Postmemory. Yale J. Criticism 2001, 14, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crownshaw, R. Photography and memory in Holocaust museums. Mortality 2007, 12, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiner, G. In anticipation of a Post Memory Boom Syndrome. Cult. Anal. 2008, 7, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Luckins, T. The Gates of Memory: Australian People's Experiences and Memories of Loss and the Great War; Curtin University Books: Perth, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Connerton, P. How Societies Remember; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wertsch, J. Voices of Collective Remembering; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Misztal, B. Theories of Social Remembering; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, M. Anzac Day: How did it become Australia’s national day? In What's Wrong With Anzac? The Militarization of Australian History; Lake, M., Reynolds, H., Eds.; University of New South Wales Press: Sydney, Australia, 2010; pp. 110–156. [Google Scholar]

- Macleod, J. The Fall and Rise of Anzac Day: 1965 and 1990. War Soc. 2002, 20, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meacham, S. Marching to a younger beat as the years take their toll of our veterans. In The Age; The Age.com: Melbourne, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Forty, A.; Küchler, S. Introduction. In The Art of Forgetting; Forty, A., Küchler, S., Eds.; Berg: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Channel Nine News, More than 40,000 at Perth Anzac service. Available online: http://news.ninemsn.com.au/national/8240921/families-ready-for-perth-dawn-service (accessed on 4 August 2012).

- Savage, K. Monument Wars: Washington DC, the National Mall and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape; University of California: Berkley, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M. Boundaries; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, A.T. The Art of Narration Changes with Time. Available online: http://www.spruethmagers.com/exhibitions/281 (accessed on 16 March 2012).

- Kemp, G. Letter from Gail Kemp (niece) with photo, medals and chain. In The Honour Roll, HMAS Sydney II Virtual Memorial; Trotter, B., Ed.; Naval Association, Finding Sydney Foundation: Sydney, Australia; pp. 2001–2010.

- Connolly, D. Ballajura War Memorial and Peace Park Dedication Ceremony. The Listening Post 2006, 1, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, G. The Habit of Commemoration and the Revival of Anzac Day. Aust. Cult. Hist. 2003, 23, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lake, M.; Reynolds, H. What's Wrong With Anzac? The Militarisation of Australian History; University of New South Wales Press: Sydney, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, N. Cast in Stone: Monuments, geography, and nationalism. Environ. Plan. D-Soc. Space 1995, 13, 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, D. The Sacralised Landscape of Glencoe: From Massacre to Mass Tourism and Back Again. Int. J. Tourism Res. 2006, 8, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, B. Constructing landscapes of power: The George Etienne Cartier monument Montreal. J. Hist. Geogr. 1998, 24, 413–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, V.; Turner, E. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, R. Space-Body-Ritual: Performativity in the City; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reader, I.; Walter, T. Introduction. In Pilgrimage in Popular Culture; Reader, I., Walter, T., Eds.; Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, S.; Eade, J. Introduction: Reframing Pilgrimage. In Reframing Pilgrimage: Cultures in Motion; Coleman, S., Eade, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Margry, P. Secular Pilgrimage: A contradiction in terms. In Shrines and Pilgimage in the Modern World: New Itineraries into the Sacred; Margry, P., Ed.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2008; pp. 13–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mayes, R. Localising National Identity: Albany's Anzacs. J. Aust. Stud. 2003, 27, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, P. The Knife Edge: Debates about Memory and History. In Memory and History in Twentieth-Century Australia; Darian-Smith, K., Hamilton, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 1994; pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Searching for a Centre that Holds. In Global Modernities; Featherstone, M., Lash, S., Robertson, R., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1995; pp. 140–154. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).