1. Introduction

In today’s world, characterised by rapid technological development, the spread of artificial intelligence (AI), and an increasingly unpredictable labour market, young people face growing pressure when making educational and career decisions. Globalisation and digitalisation have not only expanded opportunities but also multiplied uncertainties, making long-term career trajectories increasingly difficult to navigate. Recent studies emphasise that AI has a profound impact on academic development and career preparedness, simultaneously offering opportunities for personalised learning and guidance while also raising concerns about overreliance, reduced critical thinking, and ethical dilemmas regarding data use and privacy [

1] parallel, innovative counselling frameworks such as the Life-World Design model illustrate that career education must extend beyond informational guidance, cultivating students’ reflective capacity, sense of responsibility, and proactive orientation toward the future [

2]. At the same time, scholars caution that AI-driven tools in career access such as algorithmic candidate screening, virtual counselling agents, and social media profiling may inadvertently reinforce inequalities and obscure transparency, underscoring the urgent need for a socially just and ethically grounded approach to digitalised career guidance [

3].

Traditional counselling models, which primarily focus on matching abilities and interests, are increasingly insufficient for addressing these complex realities. They tend to neglect deeper dimensions of decision-making, such as personal values, emotional well-being, and the search for meaning, that are now recognised as central to fostering intrinsic motivation and sustainable engagement. Emerging developments in meaning-oriented counselling suggest that effective career guidance must transcend occupational matching and instead assist students in constructing life narratives that integrate purpose, resilience, and identity [

4,

5].

Against this backdrop, both scholars and practitioners increasingly advocate for holistic, value-oriented approaches that connect individuals’ internal resources such as values, passions, and strengths—with external opportunities and societal needs. Among the most promising of these approaches is ikigai coaching, grounded in the Japanese concept of discovering one’s purpose in life. Ikigai, literally translated as “a reason for living” extends beyond career effectiveness or goal achievement. It frames personal development as the pursuit of balance between what one loves, what one is skilled at, what the world requires, and what can provide economic sustainability [

6].

Although deeply rooted in a cultural context that prioritises harmony, collective well-being, and aesthetic sensitivity, ikigai can be meaningfully adapted to other sociocultural environments. In Slovenia, where educational and career guidance remains largely dominated by informational approaches, students increasingly articulate the need for counselling that transcends economic outcomes and incorporates dimensions of personal growth, resilience, and social contribution. Recent studies of Slovenian youth reveal evolving value orientations: while individualist values, such as personal achievement and self-expression, are increasingly prominent, collectivist dispositions, such as reliance on family, community belonging, and mutual support—remain strong among younger generations [

7]. These findings align with Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, which classify Slovenia as moderately individualistic with relatively high uncertainty avoidance and long-term orientation [

8]. This unique constellation of cultural and educational features positions Slovenia as particularly fertile ground for piloting and evaluating the potential of ikigai coaching as a complement to existing practices.

The concept of ikigai also resonates with established theoretical traditions. Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy situates the pursuit of meaning as the fundamental motivational force [

9] while Shoma Morita’s therapy emphasises acceptance and sustained engagement with everyday reality [

10]. Together with Self-Determination Theory [

11], these perspectives enrich the interpretation of ikigai as a dynamic, process-oriented construct rather than a fixed goal, highlighting presence, resilience, and personal orientation.

A practical illustration of ikigai in higher education can be found at Breda University of Applied Sciences (BUAS) in The Netherlands. Under the leadership of Professor Rutger ThielenTielen, an ikigai module has been embedded into the curriculum for several years. Their experience demonstrates that students rarely report immediate “breakthrough” moments. Instead, they describe the module as planting a seed that gains significance later, particularly at the point of graduation or during transitions into the labour market. Faculty members, especially those aligned with reflective and student-centred pedagogy, recognised its value from the outset.

Accordingly, this paper addresses research question: “How can the ikigai framework, conceptualised as a structured approach, support students in making informed study choices and shaping their career trajectories within the Slovenian context?”

The aims are to:

Present the theoretical foundations of ikigai and its relationship with motivation and career decision-making.

Analyse the advantages of ikigai coaching in comparison with traditional counselling models.

Demonstrate its applicability across three critical phases of the educational journey.

Propose a structured five-stage coaching model.

Assess the feasibility of implementing ikigai coaching in the Slovenian educational and counselling system.

Illustrate the model through an expert interview and critically evaluate its implications.

2. Ikigai

The Japanese term ikigai can be translated as “reason for living,” “purpose of existence,” or simply “that which makes life worth getting up for in the morning.” Unlike narrow definitions of professional success or material prosperity, ikigai refers to a holistic and deeply personal sense of life meaning and fulfilment. At its core lies a balance between four domains: what one loves, what one is good at, what the world needs, and what one can be rewarded for. This fourfold schema, popularised in Western coaching literature [

6] has gained wide recognition, but scholars increasingly stress that it only partially reflects the cultural depth of the original Japanese notion [

12,

13,

14].

Contemporary research by Akihiro Hasegawa, psychologist at Toyo Eiwa University, highlights the linguistic origins of the concept. The suffix

-gai is historically linked to the word

kai (seashell), a symbol of value during the Heian period (794–1185). This association reflects the idea that ikigai is something precious, embedded in the ordinariness of daily life. Expressions such as

yarigai (“value in action”) and

hatarakigai (“value in work”) illustrate how Japanese culture frames meaning as a lived, experiential quality rooted in everyday tasks [

15] Similarly, ref. [

16] defines ikigai as encompassing both small daily joys and long-term life goals, reflecting its multidimensional character.

Ikigai in the Japanese Context

Scholars stress that in Japan ikigai is not a goal-oriented tool but rather a process of daily living, aligned with cultural values of harmony, impermanence (

mono no aware), and social contribution [

17]. It often emerges through small practices: caring for family, connecting with nature, or fulfilling one’s role within the community. Ref. [

15] warns that Western functionalist interpretations risk stripping ikigai of this cultural nuance, turning it into a static “life purpose diagram.”

In Western contexts, ikigai has been popularised as a coaching model for personal effectiveness, career orientation, and goal-setting. While this has increased accessibility, scholars caution that such adaptations may oversimplify the concept and commercialise a philosophy rooted in subtle cultural practices. Authors [

12,

14] highlight that the popular four-circle diagram is effective as a heuristic, but obscures the everyday, relational, and spiritual dimensions of ikigai. Similarly, ref. [

13] emphasise that meaningful application outside Japan requires cultural adaptation rather than superficial adoption. Academic engagement with ikigai must therefore critically reflect on which elements can be meaningfully adapted, and which risk distortion if transplanted into different sociocultural contexts.

In addition, East–West cultural distinctions should be understood as historically dynamic rather than dichotomous. Since the nineteenth century, reciprocal cultural diffusion—recently amplified by globalisation—has fostered mutual influence: for instance, the widely analysed “Americanisation” of aspects of Japanese culture on the one hand, and the emergence of Western spiritual movements (e.g., New Age) drawing on Eastern religious philosophies on the other. This convergence is reflected even in contemporary global performance metrics: whereas prosperity was formerly assessed primarily through GNI/GNP/GDP, indices such as the World Happiness Report and the Global Wellbeing Indicator now incorporate social inclusion, community health, and environmental liveability—dimensions consonant with the ikigai philosophy.

Transferring ikigai into Slovenia requires sensitivity to cultural and social dynamics. Collectivist societies such as Japan often associate meaning with fulfilling community roles, whereas more individualist societies emphasise autonomy and self-actualisation. Slovenia occupies an intermediate position: while modern youth are increasingly exposed to individualist pressures (autonomy, career success), traditional communal values such as family responsibility and social contribution remain strong.

To strengthen such cultural arguments, established comparative frameworks such as Hofstede’s cultural dimensions should be employed. In [

8] classify Japan as strongly collectivist and long-term oriented, while Slovenia is moderately individualistic but with high uncertainty avoidance. These contrasts allow for a more rigorous assessment of cultural difference and adaptation, avoiding the risk of overgeneralisation.

If ikigai is to become a meaningful counselling framework in Slovenia, it must be contextualised rather than imported wholesale. Several factors are critical:

Value framework—For many Slovenian students, purpose is tied to care for family, commitment to community, or preservation of traditions. These orientations should be seen as complementing rather than opposing prevailing Western indicators of success; indeed, contemporary indices (e.g., the World Happiness Report) already integrate social inclusion, community health, and environmentally liveable contexts—values closely aligned with ikigai.

Regional diversity—Rural youth may construct meaning differently than urban peers; ikigai must allow space for modest, locally grounded life projects.

Spirituality and religion—For some, faith remains central in providing meaning; ikigai should not compete with but complement such worldviews.

Acceptance of foreign models—Slovenians are often cautious toward externally imported frameworks. Therefore, ikigai must be introduced with local narratives and metaphors—for example, being “useful in the community,” “working with wood,” or “teaching others.”

By treating ikigai not as an exotic philosophy or managerial technique, but as a comprehensive life approach, it can serve as a culturally sensitive framework for career reflection in Slovenia. Properly adapted, it offers young people a means to align their values and goals with both personal growth and social contribution, fostering more sustainable and fulfilling life choices.

3. The Theory of Motivation and Understanding Ikigai

Motivation represents the fundamental driving force behind human behaviour. It explains why individuals initiate, sustain, or abandon certain actions. Classical distinctions differentiate between intrinsic motivation (originating from within the individual) and extrinsic motivation (driven by external factors) [

18]. Yet, contemporary psychological theories expand this dichotomy, offering richer frameworks to analyse how meaning and purpose shape behaviour.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

Self-Determination Theory provides the closest alignment with the ikigai construct. It distinguishes between intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation, the latter reflecting the absence of perceived connection between action and outcome [

19].

Intrinsic motivation is particularly relevant to ikigai: it fosters sustained engagement, resilience, and a sense of fulfilment, as actions are performed out of interest and value alignment [

19]. Moreover, extrinsic motivation, when supported by autonomy, competence, and relatedness, can be internalised and become self-directed. This gradual internalisation echoes the ikigai process, in which external expectations (e.g., employability, societal needs) are reconciled with personal values [

19]. Thus, ikigai can be conceptualised as a practical framework for satisfying the three SDT needs: autonomy (discovering what one values), competence (developing skills through education and practice), and relatedness (contributing to others and society). Research shows that fulfilment of these needs is predictive of well-being, persistence, and long-term satisfaction [

19]. Beyond motivational psychology, existential perspectives enrich the understanding of ikigai.

Secondly, Logotherapy, developed by Viktor Frankl, situates meaning as the central motivational force. It stresses human capacity to endure suffering and remain resilient through values and responsibility [

9]. Within the ikigai framework, logotherapy highlights the pursuit of deeper meaning in studies, relationships, and professional life, beyond hedonic satisfaction.

Thirdly, Morita therapy, in contrast, emphasises acceptance and the cultivation of life’s meaning through everyday practices. It suggests that purpose emerges not through grand goals but through modest acts, routines, and interpersonal contributions [

10].

These perspectives reveal cultural contrasts: Frankl’s Western model emphasises active self-realisation, while Morita reflects an Eastern orientation toward coexistence and patience. For counsellors applying ikigai, this raises practical questions: should guidance emphasise striving for self-transcendence, or acceptance of circumstances? Most likely, ikigai requires a synthesis of both, acknowledging that meaning is simultaneously constructed and discovered.

Established frameworks in career counselling also provide an important backdrop. E.g., Holland’s RIASEC model [

20] classifies individuals by vocational personality types (realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, conventional) and matches them with environments. While useful for orientation, critics argue that RIASEC largely overlooks values, existential dimensions, and cultural contexts [

21]. It tends to assume linear career paths and stable identities, which may not reflect contemporary realities of non-linear, dynamic careers. In addition, Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) [

22] explains career choice through self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, and goal-setting. It highlights social and contextual influences and has been widely applied in higher education [

23]. However, SCCT does not fully capture the existential search for meaning or the role of personal purpose in study choices [

24].

Ikigai complements both frameworks by adding the dimension of meaning and social contribution. It provides what might be called a “missing fourth pillar” in career counselling: not just what fits (RIASEC), or what I can do (SCCT), but what makes life worth doing.

Rather than treating these theories as parallel, a more critical integration is necessary. Ikigai can be conceptualised as a bridge between motivational psychology and existential philosophy:

From SDT, it borrows the structure of psychological needs.

From logotherapy, the orientation toward meaning as a driver of resilience.

From Morita therapy, sensitivity to cultural context and daily practice.

From SCCT and RIASEC, practical mechanisms for career choice, which ikigai deepens by embedding them in values and purpose.

Taken together, these frameworks suggest that ikigai is neither purely motivational nor purely existential. It is best understood as a dynamic process of alignment: between personal desires, social expectations, and cultural values. This process enables individuals not only to choose a career but to construct a coherent life narrative that integrates work, relationships, and identity.

4. Ikigai Coaching

Traditional career counselling in Slovenia and elsewhere often relies on one-off assessments aptitude or IQ tests, interest inventories—and general recommendations regarding study programmes. Such approaches primarily seek alignment between an individual’s abilities and a chosen profession. While useful, they tend to overlook deeper dimensions: personal values, long-term motivation, and the broader social meaning of work. As a result, many young people experience disillusionment, a loss of purpose, or even study drop-out when confronted with mismatches between their chosen path and their deeper aspirations [

23,

25].

Ikigai coaching represents a dynamic alternative. Instead of asking only “What am I good at?”, it prompts reflective questions such as:

By integrating internal factors (passions, values, competencies) with external circumstances (societal needs, labour market opportunities), ikigai coaching fosters sustainable alignment and long-term engagement. Crucially, it is not a one-off event, but a continuous process of self-reflection and reorientation, acknowledging that life purpose can evolve and be rediscovered across different stages.

To move beyond conceptual debate, ikigai coaching requires clearer methodological definition. Literature on coaching effectiveness suggests that multi-session interventions (typically 4–8 sessions of 60–90 min) have stronger and longer-lasting effects than one-off workshops (thus, an optimal format may include):

Introductory session: 90 min for rapport building, goal-setting, and initial reflection.

Follow-up sessions: 4–6 sessions of 60 min, spread over a semester or academic year.

Format: individual coaching for deeper personal exploration, complemented by group workshops to foster peer learning.

Facilitators: trained school counsellors, psychologists, or certified coaches with expertise in motivational psychology, meaning-oriented counselling, and cultural adaptation.

Tools: value clarification cards, guided imagery, reflective journals, visual ikigai diagrams, and structured questionnaires.

Evaluation metrics: validated measures of subjective well-being (Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scales), clarity of career goals (Career Decision Self-Efficacy Scale), student engagement scales, and institutional indicators such as drop-out reduction [

26,

27].

Explicitly articulating these operational dimensions is essential for empirical testing and for embedding ikigai coaching in institutional policy frameworks. Research suggests that younger generations (particularly Generation Z) increasingly demand careers that combine financial security with social contribution and personal fulfilment [

28]. Ikigai coaching directly addresses these needs by providing structured conversations around values, expectations, and aspirations, thereby supporting students in building coherent career strategies that are both personally meaningful and socially responsive.

Among established frameworks, Holland’s RIASEC model and Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences are particularly relevant for comparison. RIASEC cathegorises individuals into six vocational types and matches them with environments [

20]. While effective for orientation, it neglects deeper motivational and existential layers. In contrast, ikigai coaching extends beyond personality–job fit to explore values and purpose, offering more sustainable career alignment [

21]. Ref. [

24] Gardner’s model highlights cognitive diversity through multiple intelligences. However, it remains primarily ability-focused. Ikigai bridges this by connecting skills to values and social impact, fostering life coherence and engagement.

Thus, ikigai coaching does not replace existing models but complements and deepens them, ensuring that career guidance captures not only what fits but also what matters.

The strength of ikigai coaching lies in its multidimensionality. It addresses cognitive, emotional, social, and existential aspects of development, qualities that are indispensable in a world where career paths are increasingly non-linear and subject to rapid change. By combining intrinsic motivation, market realities, and personal vision, ikigai provides students with a flexible compass for navigating uncertainty, fostering resilience, and achieving long-term fulfilment.

Education is a structured and long-term process aimed not only at developing knowledge and skills but also at shaping values, habits, and social responsibility. It enables individuals to participate meaningfully in society, cultivate critical thinking, and form their identities. Contemporary perspectives increasingly emphasise that learning is no longer confined to youth or formal schooling but is a lifelong process, unfolding across formal, non-formal, and informal contexts [

29]. Within this framework, education is conceptualised as a process of personal transformation and meaning-making, rather than as a mere acquisition of credentials.

The shift toward lifelong learning has become particularly urgent in light of demographic, technological, and economic changes. Slovenia, like other OECD countries, is experiencing rapid population ageing: in 2022, over 21% of its population was above 65 years [

30]. This demographic reality requires strategies that engage not only young students but also adults and older generations in reflective, adaptive learning throughout the life course. Beyond employability, lifelong learning must also cultivate mental flexibility, well-being, and a sense of purpose—dimensions that ikigai is uniquely suited to address [

31,

32]. Research has shown that meaning-oriented lifelong learning contributes to psychological well-being and social integration, particularly in contexts of demographic and technological transition.

Despite these shifts, the Slovenian educational system continues to rely heavily on informational counselling models. Career centres and school counsellors primarily provide data about study programmes, labour market trends, or scholarship opportunities. While important, such approaches seldom engage with students’ values, motivations, or long-term visions. As a result, young people often make choices driven by external expectations, leading to misaligned study paths, reduced motivation, and increased risks of drop-out.

Moreover, current models rarely address non-linear career paths. In a labour market increasingly shaped by automation and AI, career trajectories are fragmented and subject to constant reorientation. Slovenian counselling practices, however, often still operate with linear assumptions (interest → study → employment). What remains underdeveloped are frameworks that prepare students for ongoing meaning-making, adaptation, and identity re-negotiation across different stages of life.

Ikigai coaching directly responds to these gaps. By guiding students to reflect on:

autonomy (what they love and value),

competence (what they are good at and can develop),

relatedness and contribution (what the world needs), and

sustainability (what they can be rewarded for),

ikigai coaching provides a structured process for aligning inner drives with external opportunities. Unlike informational guidance, ikigai facilitates deep reflection on purpose, encouraging students to position themselves not only as future workers but also as engaged citizens with meaningful roles in society.

The relatively small scale and transparency of Slovenia’s educational system provide favourable conditions for pilot implementation. Ikigai coaching could be integrated into existing structures, for example:

Secondary schools: as part of career education courses in the final two years before study choice.

University career centres: as a complementary tool to CV workshops and job fairs, focusing on reflection and long-term direction.

Adult education programmes: to support career transitions and lifelong learning, particularly in the context of demographic ageing.

To ensure credibility, such programmes should be facilitated by trained counsellors or psychologists and supported by validated tools and outcome metrics. Suggested measures include Career Decision Self-Efficacy Scales [

26] student engagement surveys and well-being indicators [

33].

Importantly, cultural transfer cannot be taken for granted. Slovenia shares many features with Western European individualism but retains strong communal and family-based orientations. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions provide empirical grounding for such claims, classifying Slovenia as moderately individualistic with relatively high uncertainty avoidance and long-term orientation [

8]. These characteristics influence how young people interpret guidance and make study choices. If ikigai is presented merely as a foreign or exotic import, it risks scepticism among educators and students. Therefore, its introduction should rely on locally resonant metaphors and narratives (e.g., community engagement, sustainability, craftsmanship) to build trust and ensure relevance.

The Slovenian educational system faces the dual challenge of preparing young people for an uncertain labour market while simultaneously cultivating their personal growth and resilience. Current counselling models, while informative, are insufficient for this task. By embedding ikigai coaching into existing structures, Slovenia could pilot an innovative, culturally sensitive approach that aligns with lifelong learning principles, supports personal reflection, and equips students with tools for navigating uncertainty in ways that are both personally meaningful and socially sustainable.

5. Ikigai in Three Key Phases of Education

Ikigai coaching can support students at three critical stages of their educational journey: before entering higher education, during the study period, and at the transition to employment. This phase-based structure recognises that students’ needs and challenges differ at each stage, and thus counselling support must be developmentally appropriate, customised, and well-timed. The proposed five-stage coaching model is illustrated in

Figure 1.

5.1. Pre-Study Phase: Choosing the Right Path

Before entering university, students face one of the most demanding decisions: selecting a study programme. This choice is frequently shaped by external factors such as parental expectations, peer influence, or perceived labour market trends. Ikigai coaching provides structured reflection at this stage by:

using values clarification tools, reflective questionnaires, and guided coaching sessions,

helping students explore intrinsic drivers, personal strengths, and aspirations,

enabling more conscious and value-aligned study choices.

By clarifying values and reducing reliance on external pressures, ikigai contributes to more intentional decision-making, lower drop-out rates, and greater long-term satisfaction with study paths.

5.2. Study Phase: Sustaining Motivation and Identity

The university years bring new challenges, including maintaining motivation, negotiating personal identity, and questioning the meaning and relevance of academic pursuits. At this stage, ikigai coaching functions as a reflective checkpoint, encouraging students to examine:

whether their academic work aligns with personal values and goals,

how to adjust when interests or priorities evolve,

which experiences (internships, electives, extracurricular activities) best strengthen their emerging sense of purpose.

A key contribution of ikigai coaching is the fostering of intrinsic motivation, which has been shown to positively influence engagement, academic performance, and well-being [

34]. Importantly, this approach also normalises course correction, reframing it not as failure but as part of the ongoing search for meaning.

5.3. Transition Phase: From Study to Employment

At graduation, students often face a critical juncture: moving from the relatively structured academic environment into the uncertainty of the labour market. Current career support is often fragmented, emphasising technical skills such as CV writing or interview preparation, while neglecting deeper reflection on values and purpose. Ikigai coaching fills this gap by:

helping students articulate which skills and competencies they wish to apply,

clarifying which values they seek to realise in their professional lives,

identifying work environments aligned with their aspirations,

exploring where passion and competence intersect with societal value and financial sustainability.

Such structured reflection fosters career adaptability—the psychosocial resources that enable individuals to cope with changing work demands—which has been linked to smoother transitions and higher job satisfaction.

These three phases, pre-study, study, and transition, together form a continuous developmental framework. Rather than offering one-off interventions, ikigai coaching should be implemented iteratively, revisited at multiple points of the academic journey. This reflects the reality of non-linear career paths, where individuals must repeatedly re-align values, competencies, and opportunities in response to evolving personal and societal contexts,

as summarised in Table 1.

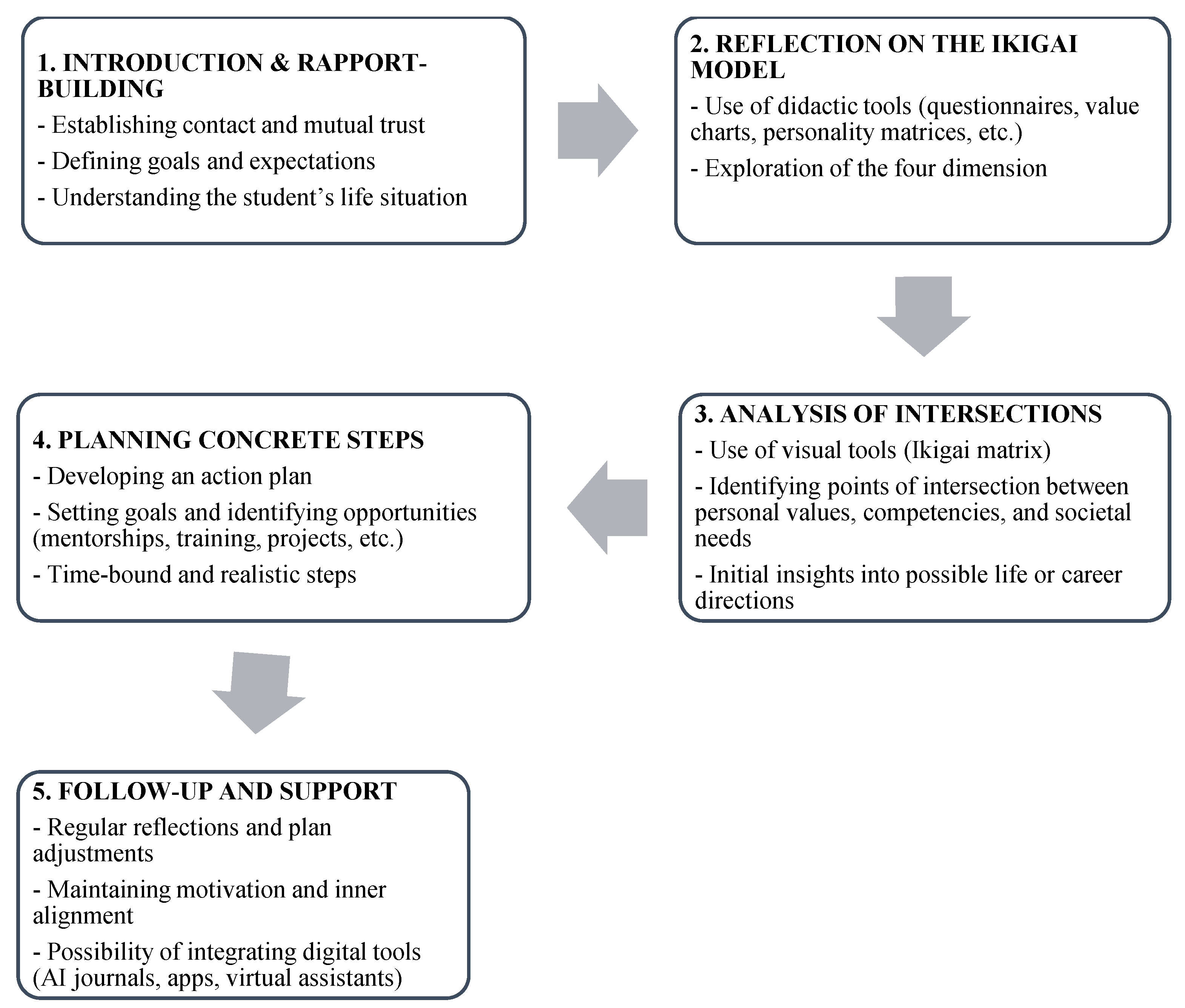

6. A Structured Process in Five Stages

The ikigai coaching process can be conceptualised as a five-stage framework consisting of an introductory phase focused on relationship-building, guided reflection, intersection analysis, planning of concrete steps, and ongoing support with monitoring. These stages are not strictly linear but rather iterative, allowing participants to revisit earlier insights whenever new challenges emerge or values change. In this way, the model functions as a flexible structure rather than a rigid protocol, recognising that career and life decisions unfold as dynamic, context-sensitive processes rather than predetermined trajectories,

as illustrated in Figure 2.

The first stage, the introductory session, establishes the foundation of the coaching relationship. Trust and psychological safety are prerequisites for authentic self-reflection, and research shows that the quality of rapport between coach and client is one of the strongest predictors of positive outcomes [

35,

36]. In this stage, the coach clarifies goals, expectations, and the framework of collaboration, while also assessing the student’s developmental stage and immediate challenges. Sessions at this stage usually last between 60 and 90 min and are designed to establish clarity of aims, build trust, and define ethical boundaries.

The second stage, guided reflection, invites students to explore the four domains of ikigai—what they love, what they are good at, what the world needs, and what they can be paid for. A range of reflective and didactic tools can be used in this process, including values clarification exercises, personality and interest questionnaires, visual metaphors, and reflective journals. Because this stage requires critical thinking, introspection, and emotional investment, it typically involves several sessions supported by self-reflection assignments outside the coaching environment.

The third stage, intersection analysis, integrates the insights gained in the reflection process. The student and coach jointly examine how the four domains intersect, often using visual aids such as the ikigai diagram to map overlaps between passion, competence, societal need, and sustainability. The outcome of this process is the creation of an emerging “personal purpose map.” However, a potential risk lies in oversimplifying the process if the diagram is treated as a prescriptive formula rather than a reflective tool, a tendency that scholars have warned against in critiques of Western adaptations of ikigai [

17].

The fourth stage, planning concrete steps, focuses on translating insights into actionable strategies. This involves identifying relevant opportunities such as internships, mentorships, or additional training, formulating specific and time-bound goals, and mapping pathways that connect personal aspirations with external opportunities. Evidence-based frameworks such as SMART goal-setting or structured career roadmaps may be particularly useful in this stage to ensure operational clarity and accountability [

37].

The fifth and final stage, ongoing support and monitoring, emphasises continuity and accountability. Through regular check-ins, students are supported in sustaining motivation, preventing drift caused by external pressures, and recalibrating goals in line with new experiences or changing circumstances. Emerging technological tools such as mobile reflection applications or AI-powered coaching journals may provide scalable ways to maintain engagement beyond traditional face-to-face settings. Sessions in this phase are typically scheduled every one to two months over an academic year, with effectiveness measured through well-being scales, clarity of career goals, reduced drop-out rates, and satisfaction surveys.

For successful implementation of this process, coaches must possess knowledge of motivational psychology and the cultural foundations of ikigai, be trained in evidence-based coaching methodologies, demonstrate strong emotional intelligence, and maintain familiarity with labour market dynamics [

38] and the structure of educational systems. Professional development programmes and certification pathways are essential to ensure quality and consistency in delivery [

39].

Institutional integration of ikigai coaching will also require the development of didactic tools such as interactive diagrams, digital reflection journals, and coaching cards focused on values and competencies. These tools can be piloted in secondary schools, university career centres, and adult education programmes, but should be accompanied by rigorous evaluation mechanisms.

While promising, the five-stage process also has limitations. It risks overreliance on highly trained facilitators, depends on cultural adaptation to avoid perceptions of exoticism, and may suffer from Westernised oversimplification if visual models are emphasised without sufficient contextualisation. Furthermore, validated outcome metrics specific to ikigai-based interventions are still lacking. Without systematic piloting and empirical evaluation, the model remains conceptual. Future research should therefore aim to test its effectiveness in practice, compare results across institutions and cultural contexts, and refine the model based on longitudinal evidence.

7. Empirical Insight: Interview with Professor Rutger Thielen (BUAS, The Netherlands)

To complement the theoretical discussion with a practical case, a semi-structured expert interview was conducted with Professor Rutger Thielen from Breda University of Applied Sciences (BUAS), where an ikigai module has been integrated into the curriculum for more than three years. The interview, carried out in April 2025 via online conversation, lasted approximately 45 min and followed a semi-structured protocol. The guiding questions focused on four thematic areas: the long-term impact of ikigai, challenges during implementation, cultural adaptation, and recommendations for higher education. Notes were transcribed immediately after the session, and selected quotations are included as illustrative evidence.

Long-Term Impact and Student Feedback

Professor Thielen highlighted that the effects of the ikigai module rarely manifest as immediate breakthroughs but rather emerge gradually across the academic trajectory. Many students, he noted, return to the insights and diagrams created during their first-year sessions when approaching graduation or early career decisions: “At first, students don’t always feel that something major has happened. But later, when they graduate, many of them come back to the diagrams and reflections they made in their first year. That’s when they realise how important it was.”

This delayed effect supports the theoretical interpretation of ikigai as a non-linear and evolving process that matures over time, reinforcing its potential as a developmental rather than a one-off intervention.

According to Thielen, a common misconception among facilitators was the expectation of dramatic “aha moments.” He emphasised that ikigai operates more as a gradual cultivation of meaning than as a sudden revelation: “Ikigai is more about planting a seed than providing instant answers. It grows slowly, and that can be frustrating if facilitators expect immediate breakthroughs.”

Interestingly, students initially exhibited a neutral attitude, whereas faculty members—particularly those with a reflective or student-centred orientation—embraced the model enthusiastically. The presence of internal champions, whom Thielen described as “ikigai cheerleaders,” proved essential for sustaining momentum and embedding the approach institutionally.

Although originating in Japan, the ikigai framework was introduced at BUAS without formal cultural adaptation. Despite this, students responded positively, suggesting a certain universality in the human search for meaning. As Thielen observed: “Even though it’s a Japanese word and concept, students here relate to it. Meaning-making is universal. The key is to present it as flexible, not prescriptive.”

This raises important questions for cross-cultural transfer. While the BUAS experience indicates that ikigai can resonate beyond its cultural origins, systematic comparative research is needed to assess how subtle cultural differences influence its interpretation and application [

13,

17]. Without such inquiry, there remains a risk of superficial adoption or unrecognised cultural mismatches.

Based on his experience, Thielen strongly discouraged the implementation of ikigai as a one-time workshop. Instead, he advocated for its integration as a recurring reflective practice embedded throughout multiple stages of study: “Don’t make it a single module with a tick-box. It works best if students revisit it at several points across their studies. That way, reflection becomes part of the culture, not just an activity.”

Such integration, he argued, enables students to return to their reflections as their values, goals, and life circumstances evolve, thereby deepening the developmental impact of the process.

Although the BUAS case offers valuable empirical insight, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, it represents a single case study and therefore lacks broad generalisability. Comparative studies across multiple European institutions—such as the University of Nova Gorica in Slovenia, where ikigai workshops are already in use—would provide a more robust empirical foundation. Second, the methodological scope of this study is limited to the perspective of one practitioner; future research should triangulate findings through student surveys, classroom observations, and longitudinal evaluation. Third, while students appeared to accept the framework positively, the absence of formal cultural adaptation raises the question of whether subtler cultural mismatches may remain unaddressed.

The BUAS experience illustrates that ikigai coaching functions most effectively as a process of discovery rather than as a diagnostic tool. Its success depends on repetition, institutional support, and the commitment of facilitators who act as advocates for reflective pedagogy. Although limited in scope, this case underscores the potential of ikigai to enrich European higher education when implemented with patience, cultural sensitivity, and methodological rigour. For Slovenia, it suggests that pilot programmes should build on both international experiences (e.g., BUAS) and local initiatives (e.g., Nova Gorica), thereby creating a more robust empirical basis for integration and evaluation.

In addition, beyond BUAS and the University of Nova Gorica, ikigai-inspired initiatives have been reported in other European contexts (e.g., pilot modules and workshops in Germany, France, and the United Kingdom). Incorporating these cases into future comparative analyses would strengthen external validity and support more nuanced cultural adaptation for Slovenia.

8. Conclusions

Ikigai coaching represents a promising and innovative addition to existing career guidance practices within the Slovenian educational system. By systematically integrating personal values, intrinsic motivation, and societal contribution into the decision-making process, it transcends traditional informational models that narrowly focus on matching skills with professions. In a context where young people increasingly seek meaning, coherence, and identity formation in their studies and careers, ikigai offers a holistic and personalised framework for reflection and orientation.

The findings of this paper suggest that, if thoughtfully implemented, ikigai coaching may reduce stress and drop-out rates, enhance personal satisfaction and academic engagement, support smoother transitions between education and the labour market, and foster resilience as well as long-term career sustainability. By addressing both existential and practical dimensions, ikigai has the potential not only to benefit individuals but also to strengthen the broader educational culture in Slovenia by encouraging reflection, responsibility, and a commitment to lifelong learning.

Despite these promising insights, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the empirical scope of the article is limited, as the analysis is largely conceptual and draws primarily on theoretical frameworks alongside a single expert interview. Broader and more systematic empirical evidence remains absent. Second, methodological constraints are evident, as no quantitative or longitudinal measures were employed, making it impossible to assess the actual impact of ikigai coaching on student outcomes. Third, while the BUAS case provides valuable insight into practical implementation, its direct transferability to Slovenia cannot be assumed; without careful cultural adaptation, there is a risk of oversimplification, superficial adoption, or even resistance from stakeholders. Finally, the literature base, although diverse, still relies in part on popular sources. Strengthening the theoretical foundation with peer-reviewed, empirically grounded studies will be essential to enhance the scholarly robustness of future work.

To validate and expand upon the conceptual contributions presented here, the paper advances conditional rather than prescriptive proposals: If pilot programmes are implemented within Slovenian secondary schools, universities, and career centres, they could yield valuable insights, provided their outcomes are systematically evaluated. If carried out with methodological rigour, empirical evaluation might combine qualitative approaches (e.g., interviews, focus groups) with quantitative measures (e.g., motivation scales, well-being surveys, and drop-out statistics) to generate robust evidence of impact. If undertaken across different European contexts (including, but not limited to, BUAS in The Netherlands and the University of Nova Gorica in Slovenia), comparative studies could identify both commonalities and culturally specific adaptations. Furthermore, the development of validated didactic and digital tools—including interactive diagrams, reflection journals, and AI-assisted coaching applications—may enhance scalability, accessibility, and user engagement, while targeted professional development could equip facilitators with the requisite cultural, motivational, and methodological expertise.

Ultimately, the relevance of ikigai coaching lies in its potential to serve as a dynamic compass for students navigating a rapidly changing world. It does not aim to replace existing counselling models but to enrich them by foregrounding meaning, identity, and long-term alignment. If introduced with cultural sensitivity, institutional support, and empirical rigour, ikigai coaching could contribute to the creation of a more modern, personalised, and humane educational system—one that enables young people not only to make informed study and career choices, but also to pursue them with deeper purpose, resilience, and long-term fulfilment.