1. Introduction

The research presented in this paper has been an initiative of the #STANDFORSOMETHING campaign coordinated by the European Youth Card Association and funded by the European Parliament. The campaign stands for youth engagement in the future of Europe and was thus organized in the context of the Conference on the Future of Europe. The program aimed to mobilize the energy of young people and deliver their messages to European decision makers through the active engagement of 21 Youth Activists from 16 countries who were eager to initiate conversations and activities concerning the future of Europe with young Europeans across the Member States.

This study aims to investigate and describe the opinions and attitudes of young people towards the European Union and bring forward their ideas and priorities to be used as a reference point on the Conference for the Future of Europe and considering the European Year of Youth (2022). The survey took place through an online questionnaire during the summer of 2021, and involved a sample of 3000 young respondents aged 16–28 who were all from EU Member States.

The views and attitudes of young people towards the European Union have been considered under-researched; however, in view of increasing the legitimacy of the EU and the involvement of young people in politics, the European Commission adopted a European Youth Strategy 2019–2027 [

1]. Furthermore, the EU aims to engage with young people with various formal and non-formal means in order to collect their views on EU policies and the future. Research suggests that young people are interested and engaged both politically and civically in various modes.

In this context, this paper offers an in-depth analysis of young people’s identity formations and their general attitudes toward the European Union and its institutions. It further examines how these attitudes relate to the EU’s eight key priority areas for youth policy, as defined by the European Commission. Particular attention is given to the perceived importance of issues such as the introduction of a common basic income, the development of digital competencies, and the modernization of educational frameworks. These thematic areas are not only central to EU policymaking but also serve as indicators of how young citizens interpret and engage with broader questions of social justice, democratic participation, and European integration—issues that are explored in detail in the empirical sections that follow. Furthermore, comparative analysis on a cross-national level is implemented using multivariate quantitative analysis methods. At this stage of analysis, the aim is to further investigate profiles of young people based on how they self-identify, their general attitude towards the EU and its institutions, and what their priority agenda is. The variables are analyzed with the use of Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA), and provide a clustering of the young respondents with similar profiles. This paper then applies Correspondence Analysis to link the profiles with other key characteristics, such as demographics (country of origin, age, educational background, etc.).

The in-depth analysis, with the use of multivariate tools, reveals patterns of behavior among youth and how these distinct profiles correlate to other important characteristics, such as their demographics and their level of identification with a European identity.

By integrating these methods, this study offers insights into how young people view the EU’s role in their lives, their priorities, and the relationship between these views and their personal demographics.

By employing a mix of quantitative and qualitative research methods, from participatory approaches to focus groups, this study reveals the hopes, concerns, and visions of young Europeans for the continent’s future. Evidently, European youth are highly concerned about issues such as climate change, education, mental health, and freedom of self-expression. They also emphasize the necessity for consistent living standards throughout Europe. A notable observation from our findings is the youth’s desire for increased awareness of European institutions and processes, and their plea to be more involved and heard in shaping their European future.

Finally, the comparative analysis, employing advanced analytical tools, revealed a clear connection between the attitudes towards the EU, the way one identifies oneself as European or not, and the issues of concern. The issues correspond to different levels of feelings and attitudes towards the EU, and, on a cross-national level, this study reveals four distinct groups of behavior detected in specific geographical areas of coherent characteristics.

2. Literature Overview

Understanding youth attitudes towards Europe and the European Union is pivotal to the continuity and legitimacy of EU institutions. While many studies depict a generally positive orientation of young people towards the EU. This is largely driven by freedoms granted by the EU, such as the ability to travel, study and work opportunities, and access to a shared European space [

2,

3,

4]. However, there is no denying the undercurrents of concern about perceived bureaucracy and democratic deficits in the union’s functioning. Recent research also reveals more complex and critical engagement. The TUI Stiftung [

5] study highlights that, although a majority of young Europeans express support for the EU, significant segments are skeptical about its democratic functioning and institutional responsiveness. Similarly, Fernández Guzmán Grassi et al. [

6] show that youth support for democracy across Europe is increasingly instrumental, with disaffection toward traditional political structures not necessarily implying disengagement, but rather a shift toward non-electoral participation. This duality is echoed in the work of Sloam and Henn [

7], who argue that youth political identity today is marked by both European belonging and a demand for deeper democratic reform. National studies, such as Myllyniemi and Kiilakoski [

8], further demonstrate how young people’s views of Europe are shaped by their values, social experiences, and concerns over social justice, making the relationship between youth and the EU contingent, multifaceted, and politically significant. This is largely driven by freedoms granted by the EU, such as the ability to travel, study, and work anywhere within its member states [

4]. However, there is no denying the undercurrents of concern about perceived bureaucracy and democratic deficits in the union’s functioning.

Concurrently, an evolving European identity among the youth is evident. Frequent youth exchanges and programs like Erasmus+ have contributed to this sentiment. As noted in the EU Youth Report 2019, young individuals are increasingly identifying both with their native countries and Europe as a whole [

9]. Yet, aspirations and concerns also occupy the minds of European youth. Major concerns encompass climate change, economic disparities, and political representation. These concerns were highlighted in the European Youth Event (EYE2020) report, which underscores a yearning for a more inclusive, sustainable, and democratic Europe. Despite the trust they place in the EU, there is a peculiar paradox in the youth’s political engagement. While their participation in EU elections might be low, this does not indicate political apathy. Many young Europeans are bypassing traditional electoral mechanisms, gravitating towards grassroots movements, online activism, and NGOs [

10].

Education stands as a significant pillar shaping these perceptions. European educational institutions, through curricular initiatives and exchange programs, have been instrumental in introducing young minds to the complexities of European integration and governance, as documented in the Trends 2018 report. However, not all perceptions have been unwaveringly positive. The aftershocks of the 2008 economic downturn and subsequent austerity measures have painted the EU in varying shades. Regions grappling with higher youth unemployment rates, for instance, have exhibited increased skepticism towards European integration [

11]. The digital realm, too, has emerged as a significant influencer. While platforms like Twitter and Facebook have been arenas for a pan-European conversation among the youth, they also occasionally serve as conduits for misinformation, thereby muddying perceptions [

12]. Moreover, significant geopolitical events like Brexit have had their ripple effects, with surveys like The Prince’s Trust [

13] indicating a majority of young Britons viewing Brexit as a potential blockade to their European opportunities.

Transcending youth perceptions, the stance towards the EU among European countries is a kaleidoscope of historical, economic, social, and political hues. For instance, the financial crisis of 2008 sowed the seeds of Euro-scepticism in severely affected countries, drawing a direct line between economic distress and EU policies [

14]. On the other hand, nations that economically benefited from the EU membership showcased a more pro-EU sentiment [

15].

Migration, particularly the crisis of 2015, has also significantly shaped public sentiment. Countries at the migration forefront, such as Italy and Greece, grappled with divergent opinions, torn between humanitarian obligations and the strain on national resources. Simultaneously, Eastern European countries exhibited increased skepticism towards the EU’s migration policies, often linking them to concerns about national sovereignty [

16].

The perception of the European Union is closely intertwined with national identities. In countries with pronounced nationalistic sentiments, there is often a struggle with concerns about their identity being diluted within a broader European framework [

17]. This sentiment is exemplified in France’s “Frexit” debates, which center around apprehensions of national sovereignty and the preservation of their unique culture against the backdrop of EU governance [

18]. The perception of the European Union is closely intertwined with national identities, and nationalist concerns about identity dilution remain salient today [

19]. For example, during the Brexit referendum in 2016, the Leave campaign deliberately invoked cultural and identity fears—emphasizing “taking back control” and border sovereignty—leading to a significant resurgence of English national identity in media discourse and public rhetoric [

20,

21].

Similarly, the Grexit debate in 2015–2016, amid the Eurozone crisis, reflected deep concerns in Greece that EU-imposed austerity packages would undermine national sovereignty and economic self-determination [

22]. Greece’s public discourse around a potential “Grexit” during the Eurozone crisis similarly reflected public anxiety about supranational control versus national autonomy, though each had distinct economic and cultural motivations [

23]. In Poland, the ruling Law and Justice party (PiS) has repeatedly framed EU judicial authority as a threat to Polish sovereignty, most notably during 2021–2022, when PiS-led constitutional challenges to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice sparked intense public debate about national autonomy [

24]. In Italy, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s government has championed a cultural-identity agenda, protecting Italian traditions, language, and food as central to its efforts, and has resisted EU attempts to impose wider regulations, highlighting concerns over EU encroachment on national heritage [

25].

In stark contrast, countries like Belgium, riddled with internal linguistic and cultural divides, find solace in the European identity, viewing it as a unifying factor amid domestic fragmentation [

26].

Historical contexts further color these perceptions. Eastern European nations, with histories of oppressive regimes, initially embraced the EU as a beacon of democratization and liberal values [

27]. Yet, with the passage of time, countries like Poland and Hungary have shown tendencies towards illiberal democracies. Their repeated clashes with the EU’s staunch democratic norms have cast shadows on public sentiment, as discussed by Dawson & Hanley [

28]. Trade and economic policies also play their part in shaping perceptions of the EU. The EU’s Single Market has garnered favor in countries like the Netherlands and Ireland due to its clear economic advantages [

29]. However, contentious issues like the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) have stirred the pot, particularly in countries with a significant agricultural backdrop, such as France [

30]. The inherent regional disparities within nations, a result of varied historical and economic trajectories, further influence views on the EU. Italy stands as a prime example, where the prosperous North often stands in stark contrast to the economically challenged South, leading to contrasting opinions on EU policies [

31,

32]. A 2019 Pew Research Center survey shows that EU support is significantly higher in former West Germany (72%) compared to the East (59%), reflecting enduring socio-economic and political divides since reunification [

33]. This pattern continues to shape voting behavior: in the 2024 European Parliament elections, the far-right AfD performed notably stronger in the East, 29.7% versus only 13% in the West. These regional disparities highlight how Eastern German perspectives on EU integration often differ sharply from those in the more economically established West [

34]. Studies have also documented a consistent urban–rural divide across Western Europe in attitudes toward EU membership. In the UK, rural and small-town voters were significantly more likely to support Brexit, whereas urban populations generally opposed it [

35].

Influence in EU governance remains a pivotal factor in shaping national stances. Powerhouses like Germany and France, due to their significant influence in EU decision-making, often view the union as a tool for global amplification [

36]. On the other hand, smaller nations, while acknowledging the benefits, sometimes express concerns about potential threats to their national autonomy [

37]. In sum, public sentiment towards the EU, spanning its vast member states, is a complex mosaic shaped by historical, economic, social, and political tapestries. As the world navigates contemporary challenges, from the digital information era to global health crises, these perceptions further evolve. Recognizing the intricate nature of these relationships becomes paramount to understanding the ever-evolving dynamics between EU member states and the union itself [

38].

In conclusion, youth attitudes toward the European Union are characterized by a blend of enthusiasm and critical engagement. Young people across Europe generally value the EU for its opportunities in mobility, education, and shared identity, but they also express skepticism about its democratic responsiveness and bureaucratic complexity. At the same time, national stances toward the EU are shaped by diverse historical legacies, regional disparities, and identity politics. From the impact of economic crises and austerity measures to the role of digital platforms and youth activism, perceptions of the EU remain deeply contingent on local context. Cultural and political identity conflicts, evident in cases like Brexit, Grexit, Poland, and Italy, highlight how national sovereignty concerns continue to shape EU attitudes. Meanwhile, intra-national differences, such as the North–South divide in Italy or East–West divides in Germany, highlight the importance of internal regional dynamics. Finally, questions of influence and representation, particularly for smaller states, remain central to broader legitimacy debates. Understanding these multidimensional and evolving perspectives provides the necessary foundation for the present study, which seeks to investigate how such tensions and aspirations manifest in contemporary youth attitudes across Europe, particularly in relation to identity, participation, and political alignment.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Implementation

This analysis draws from research conducted between June and September 2021, utilizing both quantitative and qualitative methods to offer a comprehensive overview. This research initiative involved a comprehensive quantitative survey administered online between 21 June and 15 September 2021.

The survey underlying this research was conducted in 2021 as part of a project commissioned by the European Commission through the European Youth Card Association (EYCA). This study involved the voluntary participation of young people across EU Member States and was disseminated online through official EYCA and EU platforms. No personally identifiable information was collected, and participation was fully anonymous. Prior to beginning the questionnaire, all participants were provided with a clear and comprehensive informed consent page outlining the aims of this study, their right to withdraw, and assurances of anonymity and data protection. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised 2013). Ethics approval for this study was obtained internally through the European Commission and EYCA, which approved both the survey instrument and its dissemination protocol. A blank copy of the informed consent form has been submitted to the editorial office and is available upon request. Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the European Youth Card Association (EYCA), but restrictions apply to their availability. The dataset was collected as part of a commissioned study and is not publicly available due to contractual agreements and data governance protocols. Interested researchers may contact the corresponding author or EYCA to inquire about access for academic purposes. A sample version of the questionnaire is available as

Supplementary Material.

Aimed at young individuals across the European Union, the survey was conducted online with open participation, yielding a self-selected sample of 3000 respondents under the age of 29. While this method enabled broad outreach, the self-selection process limits the representativeness of the sample, as it may overrepresent individuals who are more digitally engaged or politically interested.

To ensure a broad reach and inclusivity, the original questionnaire, crafted in English, underwent translation to accommodate the languages of the 16 participating countries. A deliberate effort was made to include regional languages and idioms, such as Catalan and Irish, to cater to a more diverse audience and ensure better comprehension. The structure of the questionnaire was segmented into three distinct sections. The initial section focused on gathering demographic data, delving into fundamental details like age and educational background. This foundational information is crucial to understanding the context and background of respondents’ views. Transitioning to the second section, participants were prompted with a series of closed-ended questions. These queries sought to gauge their attitudes and sentiments toward the European Union. The spectrum of these questions was vast, ranging from how they perceive their EU-national identity to their overarching views on the European Union’s functionality and vision. In the concluding section, the spotlight shifted to the future. Here, respondents were probed about their alignment with various proposals and recommendations set forth for the imminent Conference on the Future of Europe. This section was integral to understanding the youth’s vision and expectations for Europe’s trajectory.

Through a structured and methodical approach, this survey aimed to capture a holistic view of the young population’s perspectives, providing invaluable quantitative data to guide future decisions and strategies. This research employed a qualitative design deeply anchored in participatory methodologies, with a particular emphasis on the peer-to-peer approach. The reason for this emphasis is clear: peers often elicit more open, genuine responses from one another, leading to richer, more authentic data. Sharing common backgrounds, experiences, and languages, peers can foster a level of trust and understanding that may be challenging for traditional researchers to achieve [

39,

40].

The journey began with youth activists participating in diverse events over the summer. Their role went beyond mere participation; they were specifically trained to function as “atypical participatory researchers.” During their fieldwork, which spanned various summer activities and events, they were tasked with keen observation and interactive discussions with their peers. Their training, combined with the peer-to-peer approach, enabled the gathering of nuanced opinions, ideas, and views. Furthermore, the importance of linguistic inclusivity was recognized. Discussions were facilitated in the participants’ native or regional languages. This not only ensured clarity and comprehension but also fostered a deeper connection to European Union subjects.

The synthesis of all these experiences culminated in a focus group discussion. Here, 12 chosen youth activists convened to reflect upon and disseminate the vast array of experiences and insights acquired over the summer. The peer-to-peer approach proved vital once again, as these activists, through their shared experiences, offered a rich tapestry of grassroots perspectives. This invaluable discussion was carefully recorded and later subjected to rigorous analysis by research experts. The ensuing report meticulously integrates the findings from both quantitative and qualitative avenues, aiming to provide an enriched and holistic understanding of the sentiments of Europe’s youth.

The current paper is focused on the following key research questions:

What are the general attitudes and views of young people towards the European Union and its institutions?

How do young individuals prioritize the eight key issues outlined by the European Commission, such as common basic income, digital skills, and educational frameworks?

Are there notable similarities or differences in how young people perceive Europe and prioritize these issues based on their country of origin?

What patterns can be observed among the youth’s attitudes towards the EU, the various issues, and their identity, and how do these patterns correlate with demographics like age, country of origin, and educational background?

In order to dissect and understand these responses, the following were conducted:

- -

A comparative analysis on national levels was conducted using multivariate quantitative analysis.

- -

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) was employed to group respondents with similar profiles based on their selfidentification, attitude towards the EU, and priority concerns.

- -

Correspondence Analysis was then applied to associate these profiles with other defining characteristics of the respondents, such as age, country of origin, and educational background.

3.2. Data Analysis

The initial step of our analysis involved a comprehensive descriptive exploration of all variables. This step aimed to understand the basic characteristics of the data by assessing how respondents answered each question. It provided a clear overview of the distribution and central tendencies of each variable, setting the stage for subsequent, more detailed analyses. All variables used in the analysis are nominal or ordinal.

Following the initial exploration, we focused our attention on the seven key priorities. These priorities underwent a factor analysis using Component Analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation [

41]. Factor analysis, through PCA with Varimax rotation, helped to reduce the dimensionality of the data by identifying underlying factors. These factors grouped the priorities based on their correlations and explained the shared variance among them. Upon deriving factors from the factor analysis, we proceeded to categorize these based on their similarities. Utilizing the Hierarchical Cluster Analysis, we identified six distinct groups of respondents [

41]. Each group represents a unique cluster of respondents who shared similar perspectives and priorities.

With the groups established, chi-square tests were conducted to examine the relationship between the new cluster membership variable and various other variables. These included the original priorities, demographic details, country of origin, feelings about the EU, and identity (whether national or European). This test determined if significant associations existed between the formed groups and the aforementioned variables.

In the final step of our analysis, we utilized multi-level Correspondence Analysis [

42,

43]. This technique was employed to visualize and understand the relationships between the priority profiles (based on the PCA and clustering) and all other variables. By pairing the priority profiles with the rest of the variables, we could discern how these elements connected and interacted with one another, offering deeper insights into the patterns and relationships inherent in the data. In the first step, we analyze identity (1: European, 2: European and then national, 3: National and then European, 4: National) and attitude towards the EU (1: opposed, 2: sceptical, 3: mostly in favor but it could be better, 4: in favor). In the next step, we analyze the six profiles on priority issues with identity and attitude towards Europe to investigate whether attitudes and issues that a citizen sets as a priority correlate to their attitude towards the EU in general and their perceived identity as a European. In the next step, we proceed to analyze the country of origin with the issues and then with the rest of the demographic variables.

Finally, Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) is applied for the variables country, stance towards the EU, and identity in order to produce a comparative map [

44], bringing forth groups of countries and patterns of behavior based on similarities and differences between objects, highlighting polarizations between attitudes, issues, and countries.

To summarize, the described analysis methodically unpacks the data, from understanding basic trends to discerning relationships among variables, all aimed at comprehensively understanding the perspectives of the respondents and deciphering any differences or similarities among groups in terms of country of origin and other demographics.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

Participants in the survey provided demographic information such as age, gender, origin, current residence, education level, job status, and living area. Of them, 57.8% were female, 38.5% male, and 2.2% non-binary. The predominant age group was 18–21 (42%), followed by those aged 22–25 (32%).

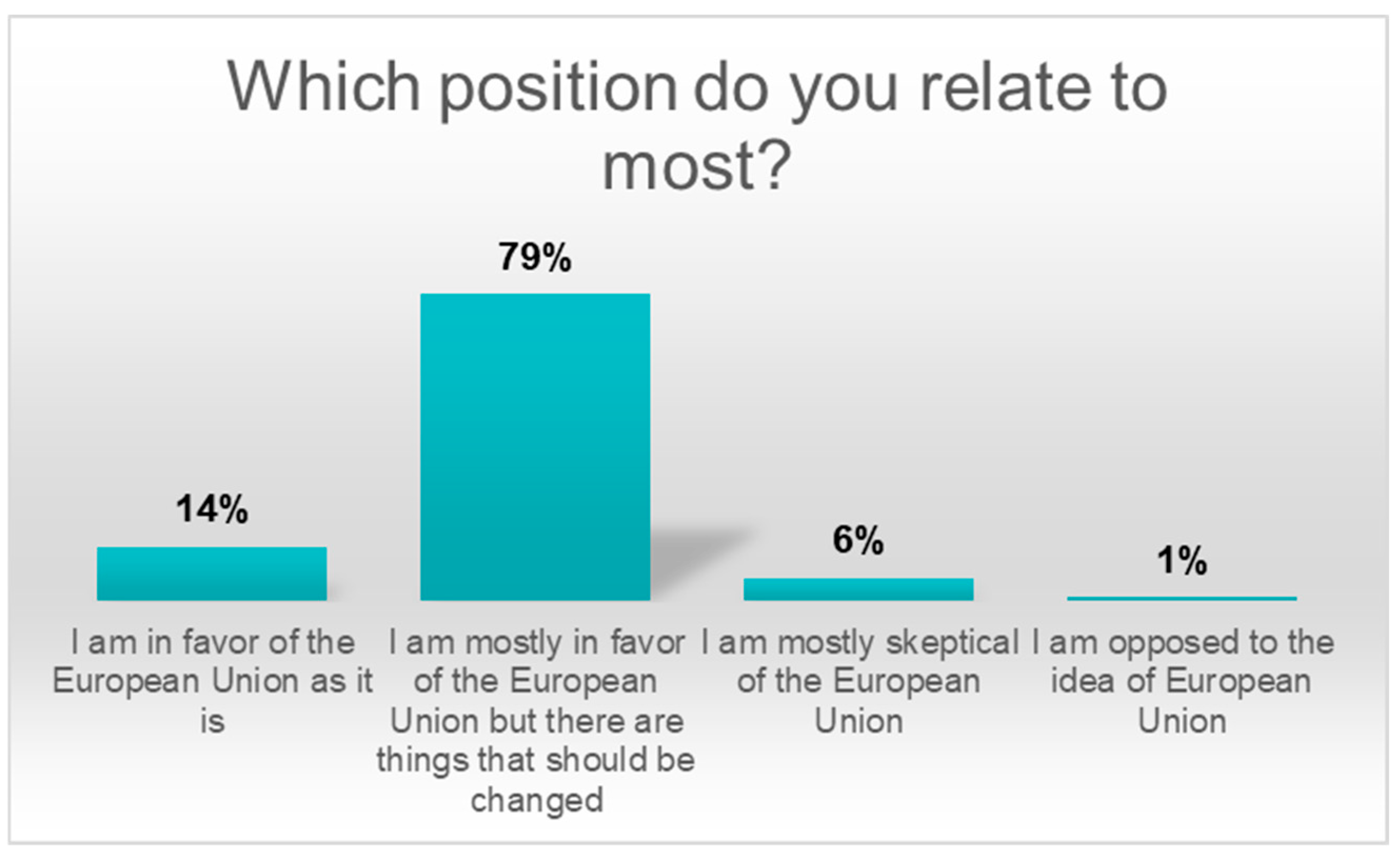

European affinity is high among the youth, with 9 in 10 supporting the EU. Specifically, 79% support the EU but see room for improvement; 14% wholly endorsed it, while 7% are skeptical or unsupportive (

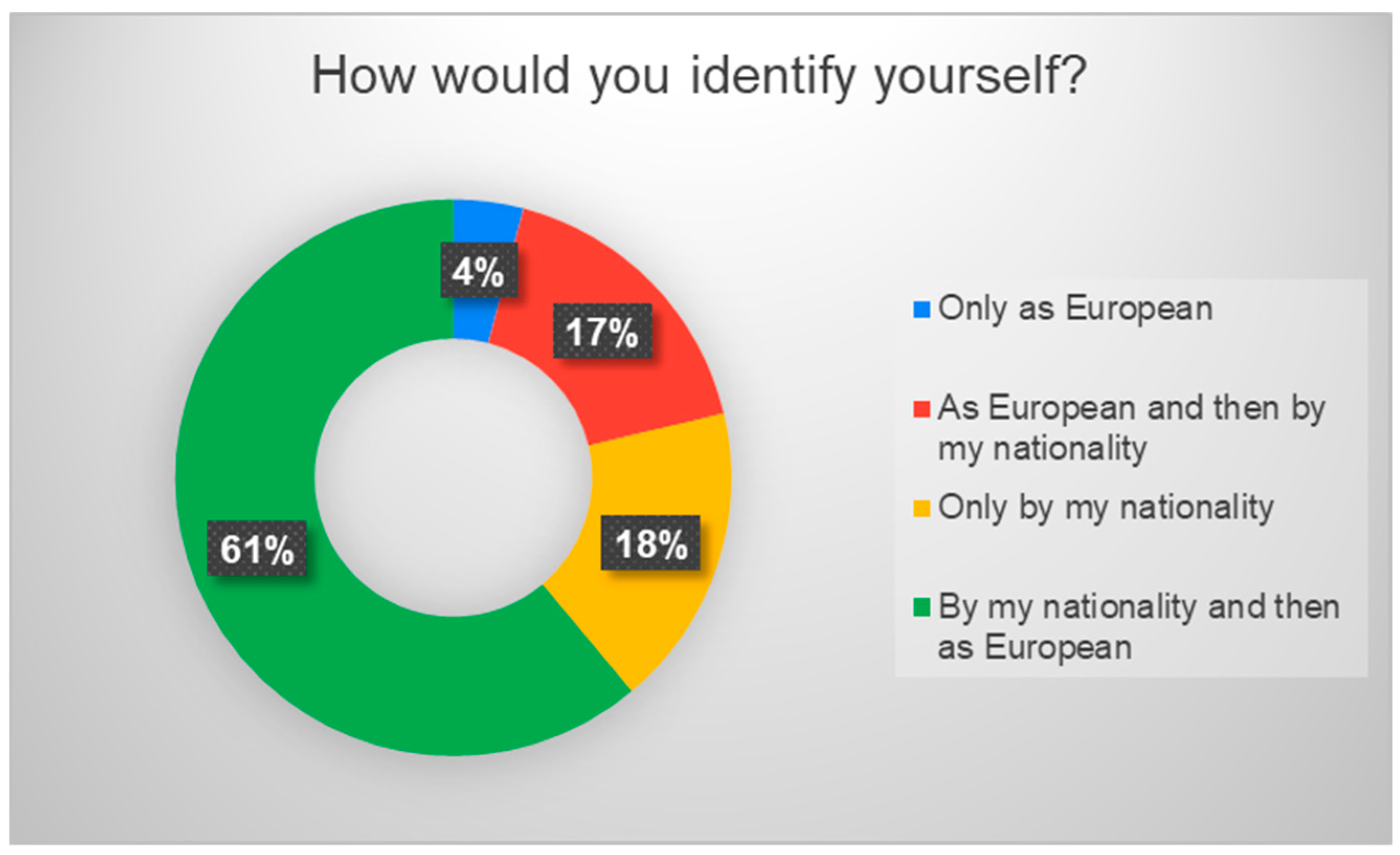

Figure 1). However, 61% prioritize national identity over European identity; 18% don’t feel European, 20% feel European first, and 4% exclusively identify as European (

Figure 2).

To voice their concerns to EU decision-makers, 35% prioritize European election participation. The 2019 European Parliament report corroborated this preference among the youth. Beyond voting, they considered petitions (15%), European activities (13%), citizen debates (11%), protests (9%), and direct approaches to authorities (8%) as effective. Only 4% viewed social media activism as effective.

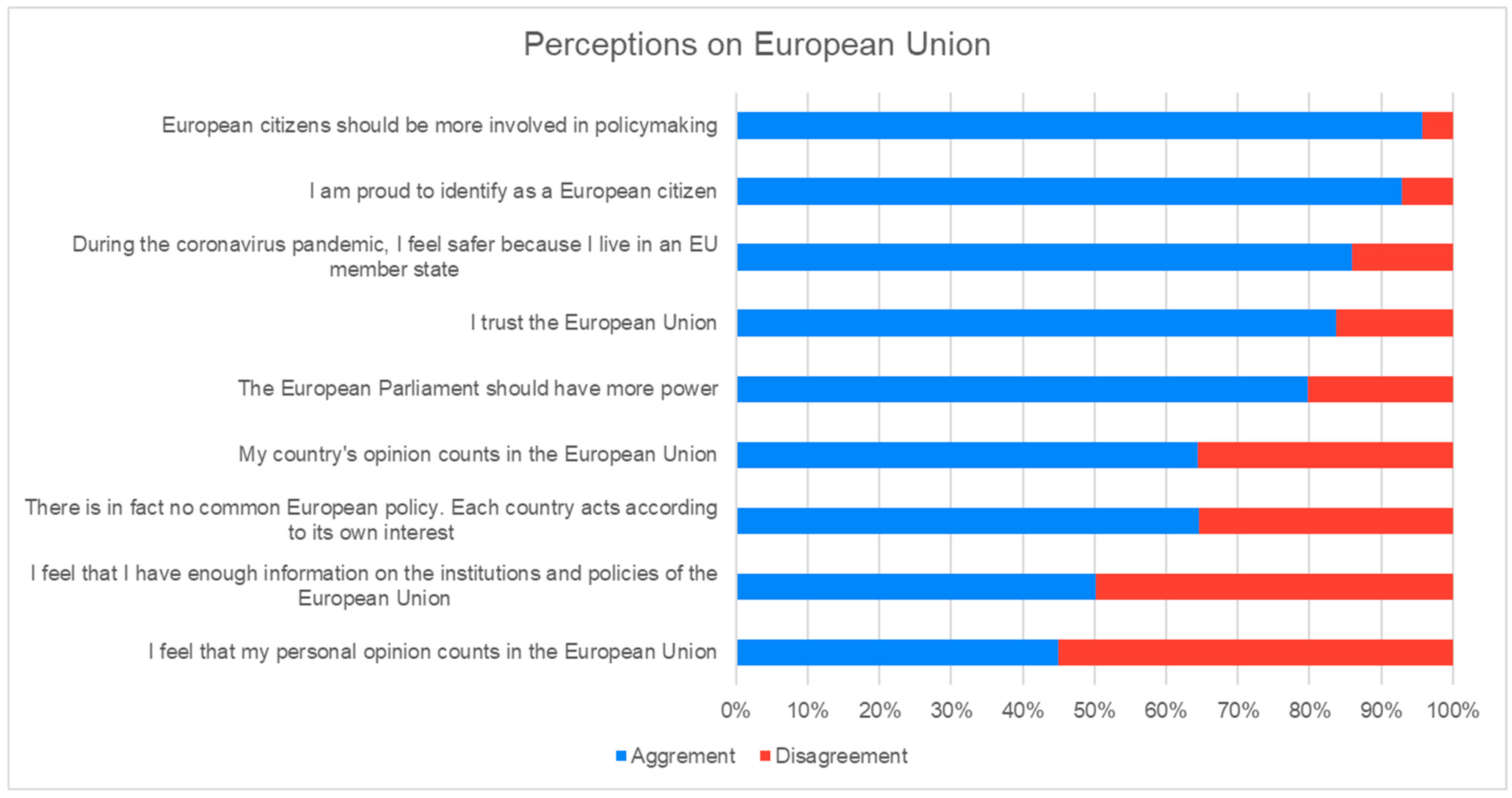

The respondents were asked to assess a set of prepositions regarding the EU and the way it functions. As

Figure 3 shows, the youth are in general proud to belong to the EU, which they trust, and this is further supported by the fact that they felt safer during the pandemic since they were European citizens. Their answers show that they want to be further involved in decision-making, that they feel they are not heard, and, in general, they report lower levels of feelings of inclusion and participation, a lack of common policies at a cross-country level, and inadequate information. To summarize, the respondents have a general good feeling of trust and pride in the EU, but, at the same time, many of them feel that it lacks power and is inaccessible to the citizens.

Regarding perceptions on Europe’s future, youth prioritize comparable educational standards, intra-EU solidarity, and equivalent living standards. They also value energy independence, shared health policies, and deeper economic cohesion. However, a unified industrial capacity, currency, and a common army are not deemed critical (

Figure 4).

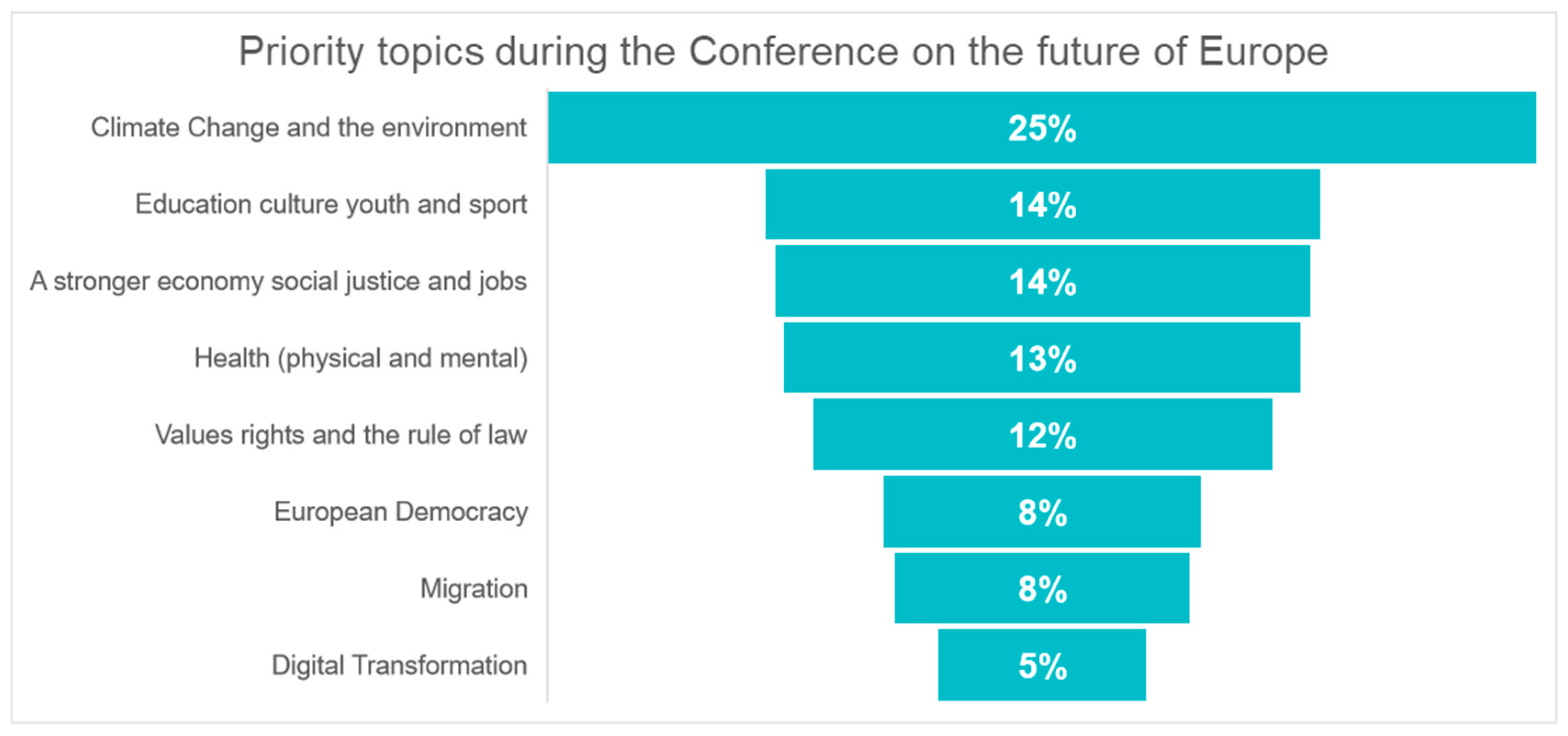

For the Conference on the Future of Europe, youth focus on climate change, environment, education, culture, sports, a robust economy, health, and values (

Figure 5). Their concerns emphasize environmental and educational issues, both current (like education) and futuristic (like climate change).

Figure 6 offers a visual illustration underscoring youth preferences, especially emphasizing climate change and education. This depiction aligns closely with the overall survey data, particularly when discussing the future trajectory of Europe, as reflected in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

Conclusively, an overarching sentiment echoing across the qualitative feedback was the youth’s eagerness for an active role in policy formulation. A considerable number articulated feelings disconnected and uninformed about significant European undertakings, notably the Conference for the Future of Europe. The overwhelming sentiment was a quest for deeper knowledge and engagement with the European Union, its institutions, and its ongoing activities. They are optimistic about the European Union’s role in sculpting their futures and are keen to be more integrally involved in its initiatives.

4.2. Comparative Multivariate Analysis

Table 1 presents the results of the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) conducted to reduce the complexity of the attitudinal variables related to policy priorities. PCA allows us to identify underlying dimensions that group together related issues, revealing patterns in how young respondents structure their policy preferences. Each component (or principal axis) represents a cluster of closely related items, with component loadings indicating the strength and direction of the association between each variable and the underlying dimension. Higher absolute loadings (typically above 0.40 or 0.50) suggest a stronger contribution of the variable to the component. For instance, if items related to “climate change,” “green economy,” and “sustainability” all load strongly on the same component, this can be interpreted as a broader environmental concern factor. The eigenvalues and explained variance indicate how much information each component captures from the original data, with the first few components usually accounting for the majority of the total variance. This reduction enables the construction of composite indicators or the interpretation of attitudinal profiles in the subsequent cluster and correspondence analyses.

Component 1: The item “A stronger economy, social justice, and jobs” has a negative factor loading of −0.968, indicating a strong inverse relationship with this component. Additionally, “Education, culture, youth, and sport” and “Health (physical and mental)” have factor loadings of −0.404 and −0.630, respectively, suggesting moderate inverse associations with Component 1.

Component 2: “Climate Change and the environment” displays a strong positive relationship with a factor loading of 0.875. Similarly, “European Democracy” and “Values, rights, and the rule of law” have factor loadings of 0.673 and 0.654, respectively, indicating positive associations with this component.

Component 3: “Digital Transformation” and “Migration” stand out with high positive factor loadings of 0.949 and 0.962, respectively, highlighting strong affiliations with Component 3.

Component 4: The item “Values, rights, and the rule of law” has a negative factor loading of −0.312, suggesting a mild inverse relationship with Component 4.

Component 5: “Education, culture, youth, and sport” and “Values, rights, and the rule of law” both have negative factor loadings, −0.628 and −0.348, respectively, indicating inverse relationships with Component 5.

Following the factor analysis, a Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) was conducted on the five extracted factors in order to identify distinct respondent profiles based on shared patterns of policy preferences. HCA is an unsupervised classification technique that groups individuals into clusters by minimizing within-group variance and maximizing between-group variance, without requiring a predefined number of clusters. In this study, Ward’s method was employed, a variance-minimizing approach particularly suitable for factor-based clustering, as it tends to create compact, well-separated clusters (Galbraith et. al, 2002). The resulting dendrogram revealed a clear six-cluster solution, each representing a unique pattern of issue prioritization among respondents. These clusters are summarized below:

Cluster 1: Democracy and rule of law;

Cluster 2: Climate;

Cluster 3: Migration;

Cluster 4: Economy, jobs, social justice;

Cluster 5: Digital transformation;

Cluster 6: Education and health.

This cluster embodies respondents who prioritize democratic processes and the enforcement of the rule of law. Their concerns center around ensuring that European institutions uphold legal standards and champion democratic ideals.

Respondents in this group emphasize the importance of addressing climate change and ensuring environmental sustainability. Their views resonate with the pressing global need for climate action and environmental conservation.

This cluster encapsulates individuals whose primary concerns revolve around migration issues. They are keenly focused on understanding and addressing the challenges and opportunities related to migration in Europe.

Encompassing economic facets, this cluster brings together respondents who place a premium on a robust economy, job creation, and the principles of social justice. Their priorities reflect a desire for economic stability and equitable wealth distribution.

Individuals in this cluster are forward-looking, emphasizing the significance of embracing digital advancements. Their concerns spotlight the transformative power of technology and the importance of digital inclusivity.

This group prioritizes health (both physical and mental) and education. Respondents in this cluster underscore the importance of robust healthcare systems and comprehensive educational frameworks as pillars for a progressive European society.

Having identified the distinct clusters from the hierarchical analysis, we proceed to examine more deeply the relationships between various categorical variables. This further exploration will be segmented into distinct analytical stages, each building upon the previous, to provide a comprehensive understanding of our dataset.

Initially, we employed Chi-Square tests for each pair of variables to see if significant dependencies existed. Building on the findings from the chi-square tests, we undertook correspondence analysis. This technique visually represented associations between categorical variables, offering a geometric perspective on relationships among categories. Our first correspondence analysis focused on two primary variables: ‘Identity’ and attitudes ‘In Favor or Against the EU’. This furnished insights into how one’s identity might have influenced one’s stance towards the European Union. Subsequently, we juxtaposed these two variables (‘Identity’ and attitudes towards the EU) against the clusters we had discerned concerning priority issues. This step was pivotal as it revealed whether and how respondents’ attitudes towards the EU and their self-identity correlated with their prioritized issues.

In the subsequent phase, we expanded our correspondence analysis to incorporate demographic variables. Specifically, we explored relationships between the clusters related to priority issues and variables such as ‘Gender’, ‘Age’, ‘Education’, and ‘Residence Area’. This helped ascertain how these demographic factors might have influenced respondents’ priorities. Finally, in our cross-national examination, we compared the clusters with the ‘Country’ variable. This helped identify any nation-specific trends or patterns in the data, allowing us to discern how respondents from different countries might have had varying priorities or attitudes and subsequently their attitudes towards the EU and whether they tended to incorporate a European identity or not. A joint correspondence analysis of all three variables from the second step produced a comparative map of Europe where countries were grouped with identity and stance towards the EU.

To aid interpretation of the correspondence analysis and multidimensional plots presented in the following sections, it is important to briefly clarify how these visualizations should be read. Both the horizontal (Dimension 1) and vertical (Dimension 2) axes represent the principal dimensions extracted from the data, capturing the greatest variance in the relationships between categories. The horizontal axis typically reflects the dominant contrast in the data (i.e., the most important differentiating factor), while the vertical axis accounts for the second most significant source of variation. The positioning of categories (e.g., age groups, issue priorities, identity types) on the plot reflects their relative association: the closer two points are, the stronger their connection. The distance from the origin indicates how much a category contributes to the overall structure of the dimensions, while the percentage of inertia shows how much variance is explained by each axis. These figures provide an intuitive visual summary of complex associations revealed through multivariate analysis. Key findings are summarized in the main text, while full component loadings and interpretations are provided in the accompanying tables.

4.3. Step 1: Exploring Identity and Stance Towards the EU

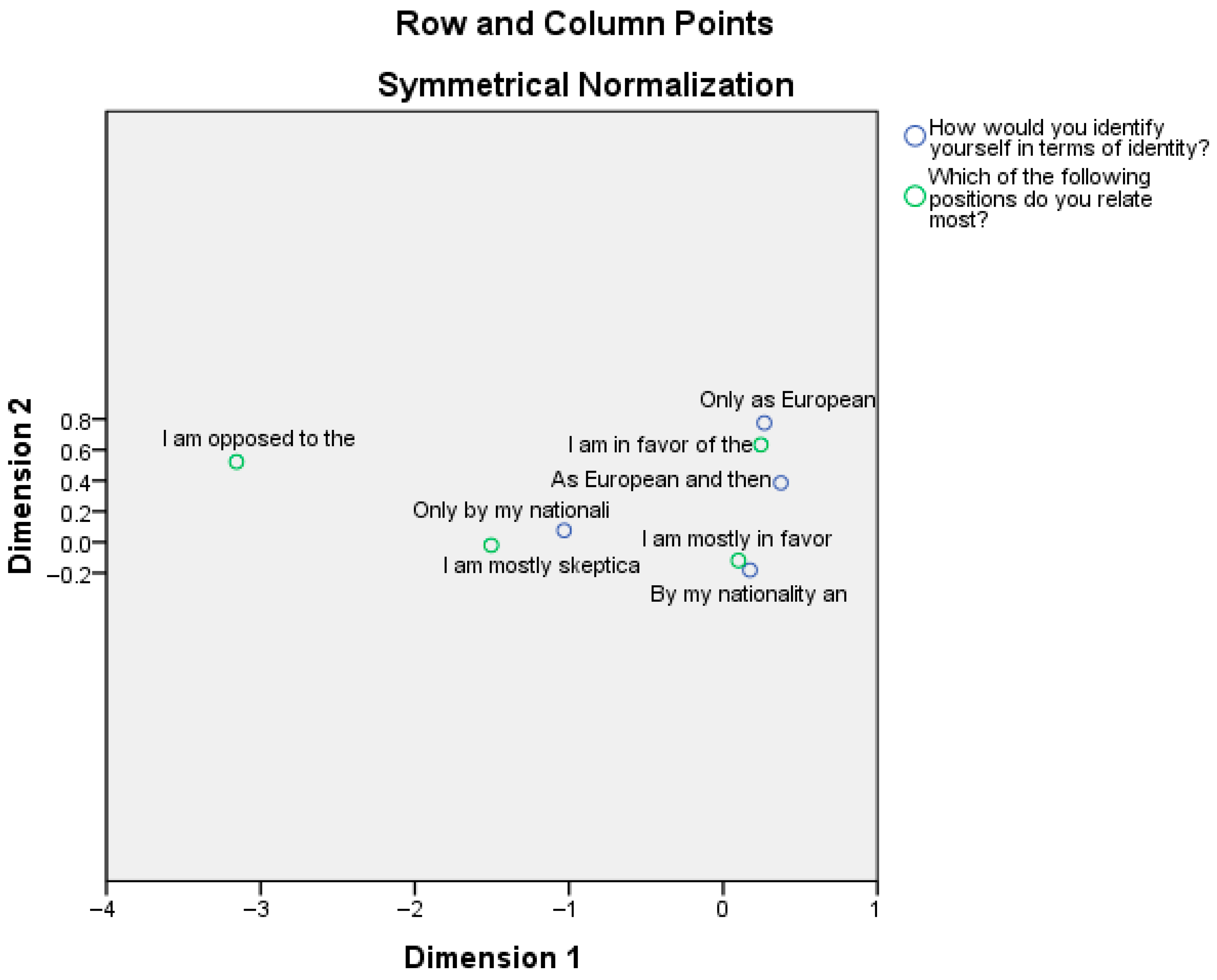

Our chi-square test confirms a significant relationship between the variables ‘Identity’ and ‘Stance to the EU’ (p = 0, df = 9). The subsequent correspondence analysis reveals that one dominant dimension accounts for an impressive 90.9% of the inertia.

This dimension vividly illustrates a dichotomy. On one end, we find individuals who harbor opposition or skepticism towards the EU. This group predominantly identifies with their national identity alone. On the opposite spectrum, there are individuals who are primarily or wholly supportive of the EU. These respondents predominantly feel a strong European identity, often putting it before or alongside their national identity.

Figure 7 presents a biplot, offering a visual representation of each item’s scores on a two-dimensional Cartesian plane. Here, the trend is evident: the more nationalistic one’s identity, the more likely they are to oppose or be skeptical of the EU. Conversely, those who consider themselves primarily or wholly European typically show strong support for the EU.

A noteworthy observation emerges for individuals who express moderate skepticism and possess a mixed identity, recognizing both their national and European identities. The progression from opposition to support for the EU aligns with the shift from a purely national identity to a European-centric identity. Thus, the underlying narrative can be summarized as: [Opposition-National]→[Skepticism-Mixed Identity]→[Support-European Identity].

In essence, the extent of one’s opposition to the EU inversely relates to their inclination towards a European identity, suggesting that attitudes toward the EU and personal identity are deeply interconnected.

4.4. Step 2: Identity and Stance Towards the EU Compared to Issues

Our analyses consistently indicate a significant relationship between personal identity, stance towards the EU, and the priority issue clusters. Specifically, the chi-square tests confirm significant dependencies for both pairings: ‘Identity and Priority Issues’ (p = 0, df = 15) and ‘Stance to the EU and Priority Issues’ (p = 0, df = 15).

Performing correspondence analysis between stance towards the EU and the six priority issue clusters, we uncover two primary dimensions that together account for 93.7% of the data’s variability (

Figure 8):

The First Dimension captures a clear dichotomy. On one side, those opposing or skeptical of the EU are predominantly associated with clusters 3 (Migration) and 4 (Economy, Social Justice, Jobs). On the other hand, those supportive of the EU align more closely with clusters 1 (Democracy, Rule of Law) and 2 (Climate).

The Second Dimension shows the intensity of one’s sentiments, either against or in favor of the EU, and maps these feelings to their priority issues. Here, cluster 3 (Migration) stands out as being linked with opposition to the EU, whereas cluster 2 (Climate Change) is associated with strong EU support. Interestingly, the remaining clusters seem to collectively gravitate towards the other end of this dimension, suggesting a deep connection between stance towards the EU and these issues.

In the pairing of identity and priority issues, the results reveal an even more pronounced relationship. The correspondence analysis uncovers one predominant axis that explains a significant 93.5% of the variance.

According to the biplot depicted in

Figure 9, those who predominantly identify as European or consider themselves European first before their national identity are closely associated with clusters 1, 2, and 5 (Democracy, Rule of Law, Climate, Digital Transformation). Conversely, individuals with a staunch national identity, excluding a European identity, correlate with clusters 3, 4, and 6 (Migration, Economy, Social Justice, and Jobs, Education, and Health.

This axis distinctly demonstrates how one’s sense of identity, whether predominantly European or strictly national, aligns with particular priority issues.

The six clusters identified, when connected with EU attitudes, delineate a thematic dichotomy based on the nature of the issues and the perceptions tied to them.

Euroscepticism-Associated Clusters: Clusters connected to skepticism towards the EU primarily revolve around issues that have been contentious within the European discourse and have frequently been used to critique the EU’s handling or involvement.

Cluster 3 (Migration): Migration, especially in recent years, has been a hot-button issue within the EU. The migrant crisis and concerns related to border security and cultural integration have been points of contention for many.

Cluster 4 (Economy, Social Justice, and Jobs): Economic disparities, unemployment rates, and social justice matters have often been focal points for criticism against the EU, especially from member countries facing economic challenges.

Cluster 6 (Education and Health): While not as contentious as migration or economic issues, education and health can be areas where individuals feel the EU either oversteps its bounds or does not provide enough support, leading to skepticism.

Positive EU Attitudes-Associated Clusters: Clusters connected to positive attitudes towards the EU represent broader, overarching principles or forward-looking goals that the European Union aspires to achieve and that are integral to its foundational ethos.

Cluster 1 (Democracy, Rule of Law): These are cornerstones of the European Union. Advocates appreciate the EU for its emphasis on democratic values and maintaining the rule of law among member states.

Cluster 2 (Climate Change): The EU’s dedication to combating climate change and setting environmental standards is seen positively by many, associating it with progressive and necessary action.

Cluster 5 (Digital Transformation): This signifies modernization, innovation, and the future, emphasizing the EU’s role in pushing the continent forward in the digital age.

In summary, the clusters associated with Euroscepticism typically represent areas of challenge and contention within the EU, while those linked with positive EU attitudes symbolize foundational principles or future-oriented aspirations of the Union.

4.5. Step 3: Issues and Demographics

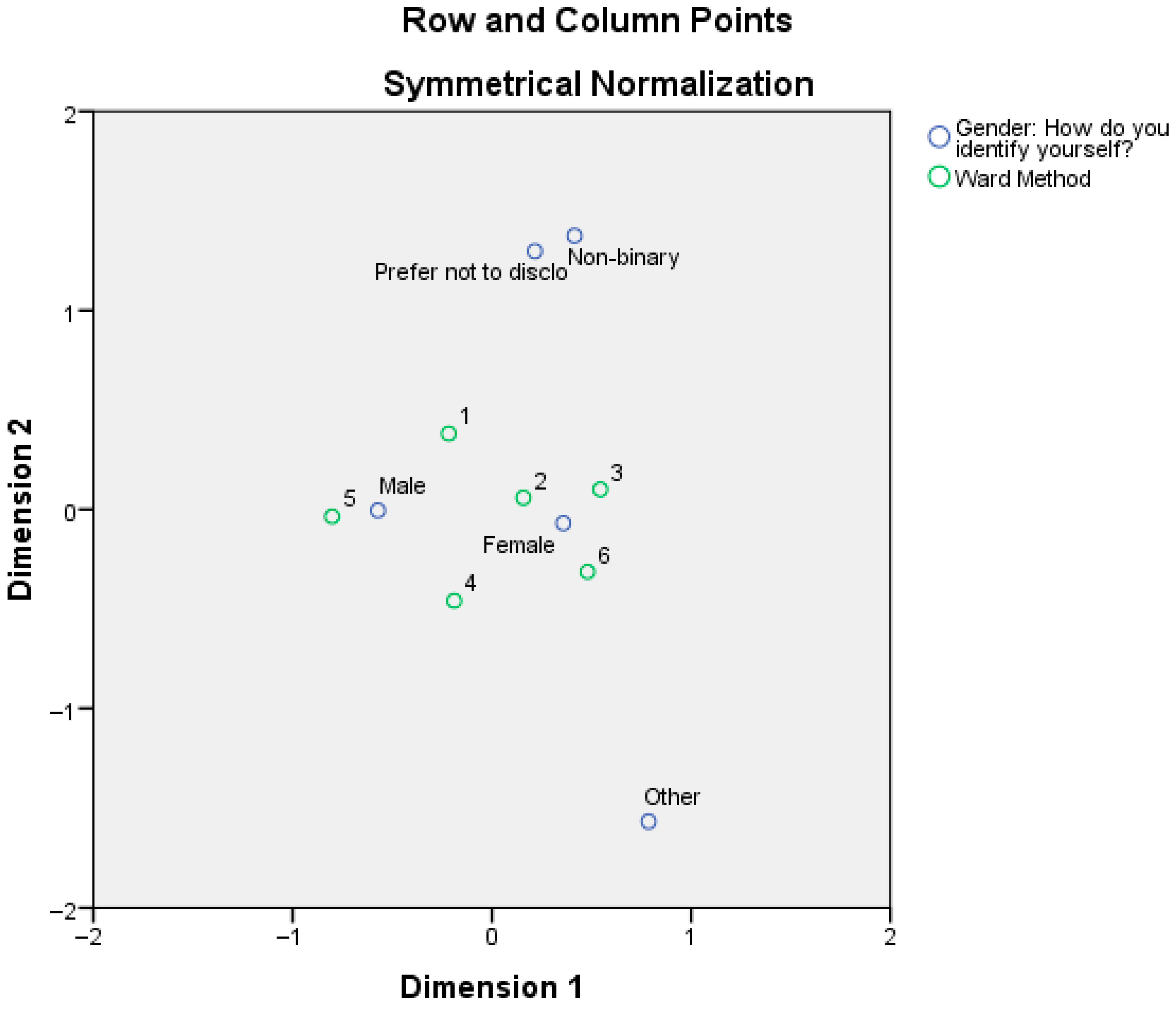

When exploring the relationship between gender identification and respondents’ priorities, as indicated by the six clusters previously identified, a chi-square test revealed a statistically significant association (p = 0, df = 20). To search deeper for patterns and relationships in the data, we applied correspondence analysis. The analysis yielded two principal dimensions that together account for a substantial 96.9% of the total variance observed in the associations.

The first dimension illuminates a clear differentiation between genders in terms of their alignment with the defined issue clusters

Figure 10). On one side of this axis, females prominently align with clusters 3 (Migration) and 6 (Education and Health). Opposing this, males are more closely associated with clusters 4 (Economy, Jobs, Social Justice) and 5 (Digital Transformation).

The second dimension brought forward a distinction between non-binary respondents and the rest, where non-binary individuals predominantly resonate with cluster 1 (Democracy and Rule of Law). In contrast, the other categories of gender identification gravitate away from this, encompassing a broader range of the issue clusters.

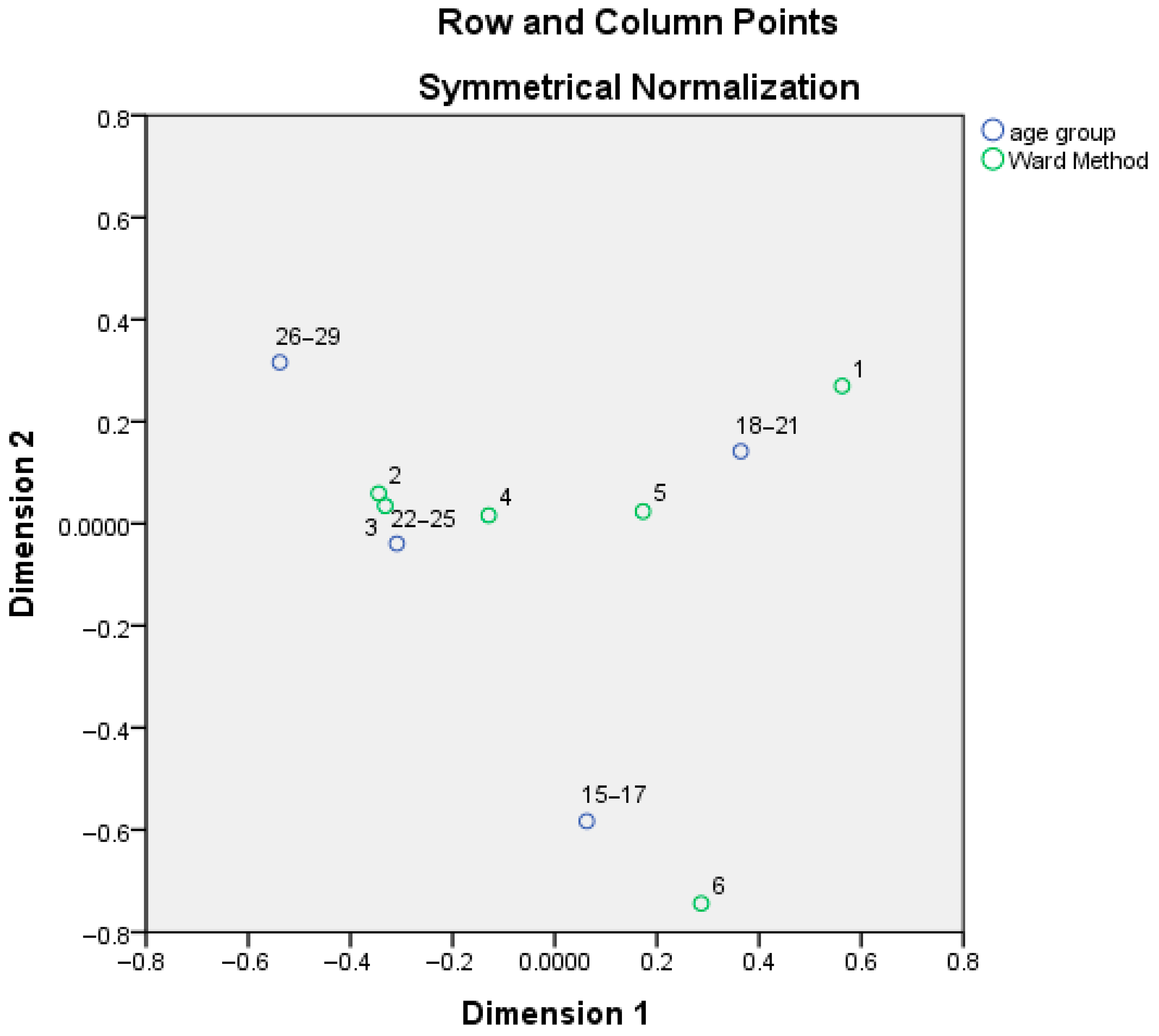

Upon examining the relationship between age groups and the six previously defined issue clusters, statistical analysis showed a significant connection, as determined by a chi-square test (p = 0, df = 20). Further exploration through correspondence analysis revealed two primary dimensions, capturing a cumulative 90.8% of the observed variance in the associations.

The first dimension prominently distinguishes age groups in their alignment with specific issue clusters (

Figure 11). On one end, younger age groups, specifically those aged 15–17 and 18–21, prominently align with clusters 1 (Democracy and Rule of Law), 5 (Digital Transformation), and 6 (Education and Health). In contrast, the slightly older cohorts, those aged 22–25 and 26–29, are closely associated with clusters 2 (Climate), 3 (Migration), and 4 (Economy, Jobs, Social Justice).

The secondary dimension underscores a more focused distinction. The youngest age bracket, 15–17, is distinctly connected to cluster 6 (Education and Health). Contrarily, the remaining age groups gravitate away from this cluster, encapsulating a broader range of the defined issue clusters. These insights highlight the varied perspectives across age groups, indicating the evolving priorities and concerns as individuals transition from their teenage years to their late twenties.

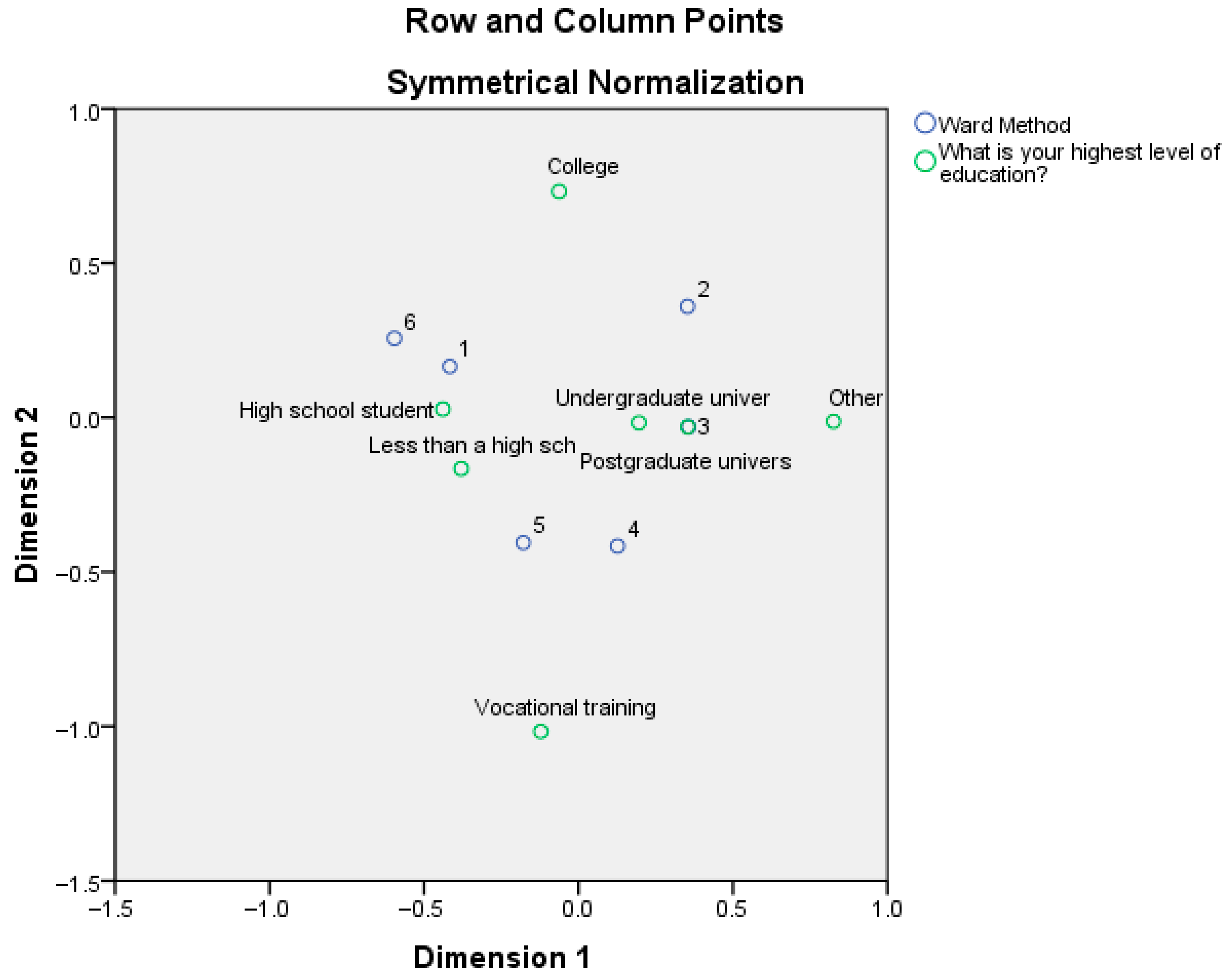

A statistical examination between education levels and the six identified issue clusters revealed a significant association, confirmed by a chi-square test (p = 0, df = 30). Looking deeper into this relationship through correspondence analysis, two principal dimensions emerged, accounting for 82.4% of the overall variance in the data.

At one end of the spectrum (

Figure 12), we find younger individuals who are still navigating their educational journeys, i.e., high school or college students. Their predominant concerns align with clusters 1 (Democracy and Rule of Law), 5 (Digital Transformation), and 6 (Education and Health). On the opposing end, older youths, who have achieved university degrees or even pursued postgraduate studies, display a notable inclination towards clusters 2 (Climate), 3 (Migration), and 4 (Economy, Jobs, Social Justice).

Similarly, students in vocational training stand closer to 4 (Economy, Jobs, Social Justice) and 5 (Digital Transformation). In contrast, individuals during their college education seem to prioritize issues encapsulated within cluster 2 (Climate). This analysis underscores the priority perspectives brought about by different stages and types of education, revealing how academic progression might influence one’s priorities and viewpoints on broader societal issues.

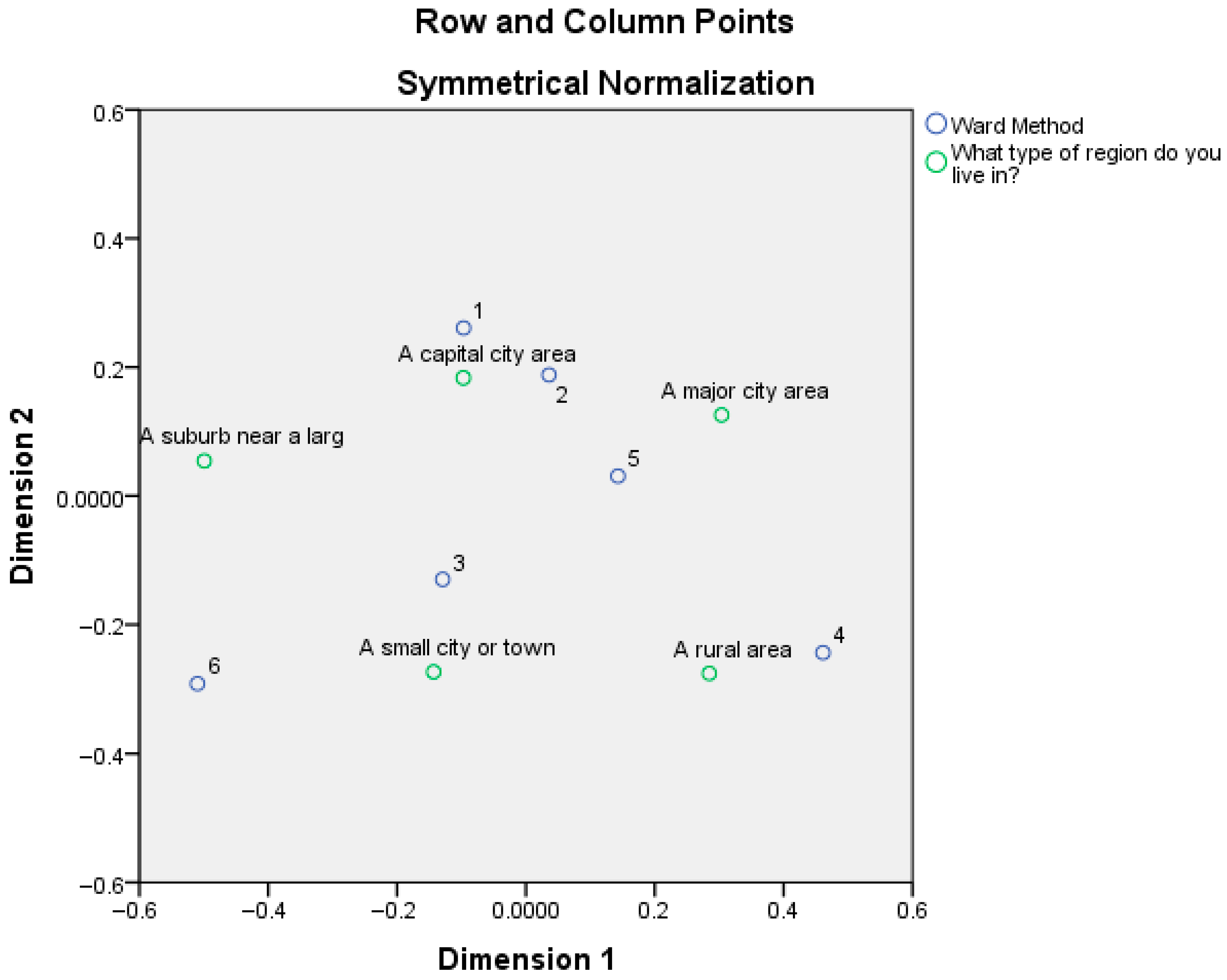

A robust statistical relationship between the type of area in which participants reside and their concerns, as represented by the six issue clusters, was established, affirmed by a chi-square test (p = 0, df = 25). When conducting a correspondence analysis to gain a more nuanced understanding of this relationship, two pivotal dimensions were identified, together explaining 75.9% of the total inertia in the data.

The first dimension accentuates the distinction between proximity to urban hubs (

Figure 13). On one side, we find those residing in suburbs adjacent to large cities. Their primary concerns align predominantly with clusters 1 (Democracy and Rule of Law) and 6 (Education and Health). Contrasting this are the residents of major cities, whose concerns chiefly resonate with clusters 2 (Climate) and 5 (Digital Transformation).

The second dimension emphasizes the difference between living in the epicenter of governance versus more remote or less populated settings. On one end, individuals living in capital cities showcase an inclination towards clusters 1 (Democracy and Rule of Law), 2 (Climate), and 5 (Digital Transformation). Notably, these clusters have been previously associated with a more European identity and positive attitudes towards the EU. This may hint at a more cosmopolitan outlook prevalent in urban centers, where exposure to diverse perspectives fosters a broader European sentiment.

Conversely, those who reside in smaller towns or rural areas lean towards issues encapsulated within clusters 3 (Migration), 4 (Economy, Jobs, Social Justice), and 6 (Education and Health). Earlier, these clusters were linked to euro skepticism and a stronger alignment with national, rather than European, identity. This finding can be reflective of localized concerns and perhaps a sense of detachment or disillusionment with larger European narratives.

In essence, one’s geographic milieu seems to frame not just their immediate concerns but also broader orientations towards Europe. The cosmopolitan vibe of urban hubs appears to engender a stronger European identity, while smaller locales seem to emphasize more localized, nationally centered perspectives. This urban–rural dichotomy is a testament to the multifaceted nature of European identity and sentiment, shaped significantly by one’s immediate surroundings.

4.6. A Comparative Mapping of the EU on Issues and Attitudes

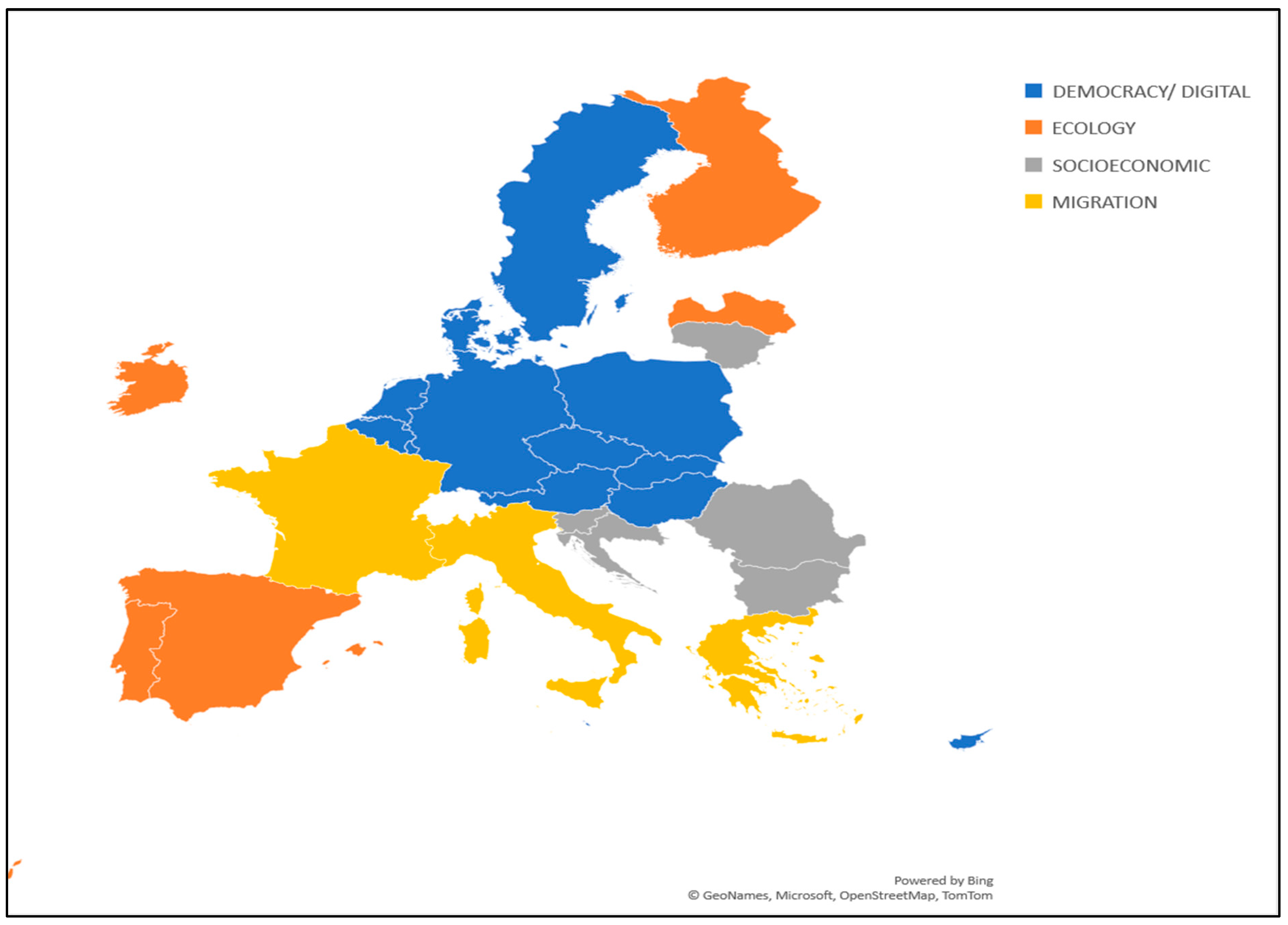

A cross-national comparative approach is now followed when correspondence is applied for the six issue clusters and the country of origin. Chi-square test rejects the independence hypothesis; therefore, the two characteristics are significantly correlated (p = 0, df = 130).

The intensive examination of the correspondence analysis output results in four main typologies of the countries when it comes to their priority issues among the youth. Each profile is found in each one of the quadrants of the Cartesian field (biplot in

Figure 14). In

Figure 15, the results are represented in a geographical map.

5. More Specifically

- (1)

Upper Left Quadrant:

Countries: Germany, the Netherlands, Malta, Austria, Belgium, Poland, Hungary, Cyprus, Sweden, and Luxembourg.

Priority Issues: Clusters 1 (Democracy and rule of law) and 5 (Digital transformation).

These countries, mostly from Central and Western Europe, have traditionally played strong roles in shaping the EU’s democratic principles and have been at the forefront of digital transformation. Their economies and infrastructures have evolved rapidly in the digital age. The association with clusters 1 and 5 suggests these nations prioritize democratic values, the rule of law, and digital innovation.

- (2)

Upper Right Quadrant:

Countries: Romania, Slovenia, Bulgaria, and Croatia.

Priority Issues: Clusters 6 (Education and health) and 4 (Economy, jobs, social justice).

Countries in this quadrant hail from Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Historically, they have gone through significant socio-economic transformations since the end of the Cold War. Their association with clusters 6 and 4 underscores their current emphasis on improving educational and healthcare infrastructures, as well as addressing challenges related to the economy, job security, and social justice.

- (3)

Bottom Left Quadrant:

Countries: Greece, Italy, and France.

Priority Issues: Migration.

Given their Mediterranean coastlines, these nations have been central in the ongoing discussions and challenges related to migration to the EU. They have directly faced the brunt of migration waves and have been significant entry points for migrants and refugees. Their placement in this quadrant indicates the paramount importance of migration issues for these nations [

45].

- (4)

Bottom Right Quadrant:

Countries: Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Finland.

Priority Issues: Cluster 2 (Climate).

Geographically diverse, these countries share a commitment to tackling climate-related challenges. Given their varied terrains and ecosystems—from the Arctic conditions in Finland to the Mediterranean climates of Spain and Portugal—these nations have a vested interest in addressing climate change. Their association with cluster 2 emphasizes the importance of environmental sustainability and climate action in their national and regional policies.

In general, the biplot positions highlight both shared and unique challenges facing these European nations. The quadrants emphasize the balance between traditional EU values (like democracy) and emerging global challenges (such as digital transformation and climate change).

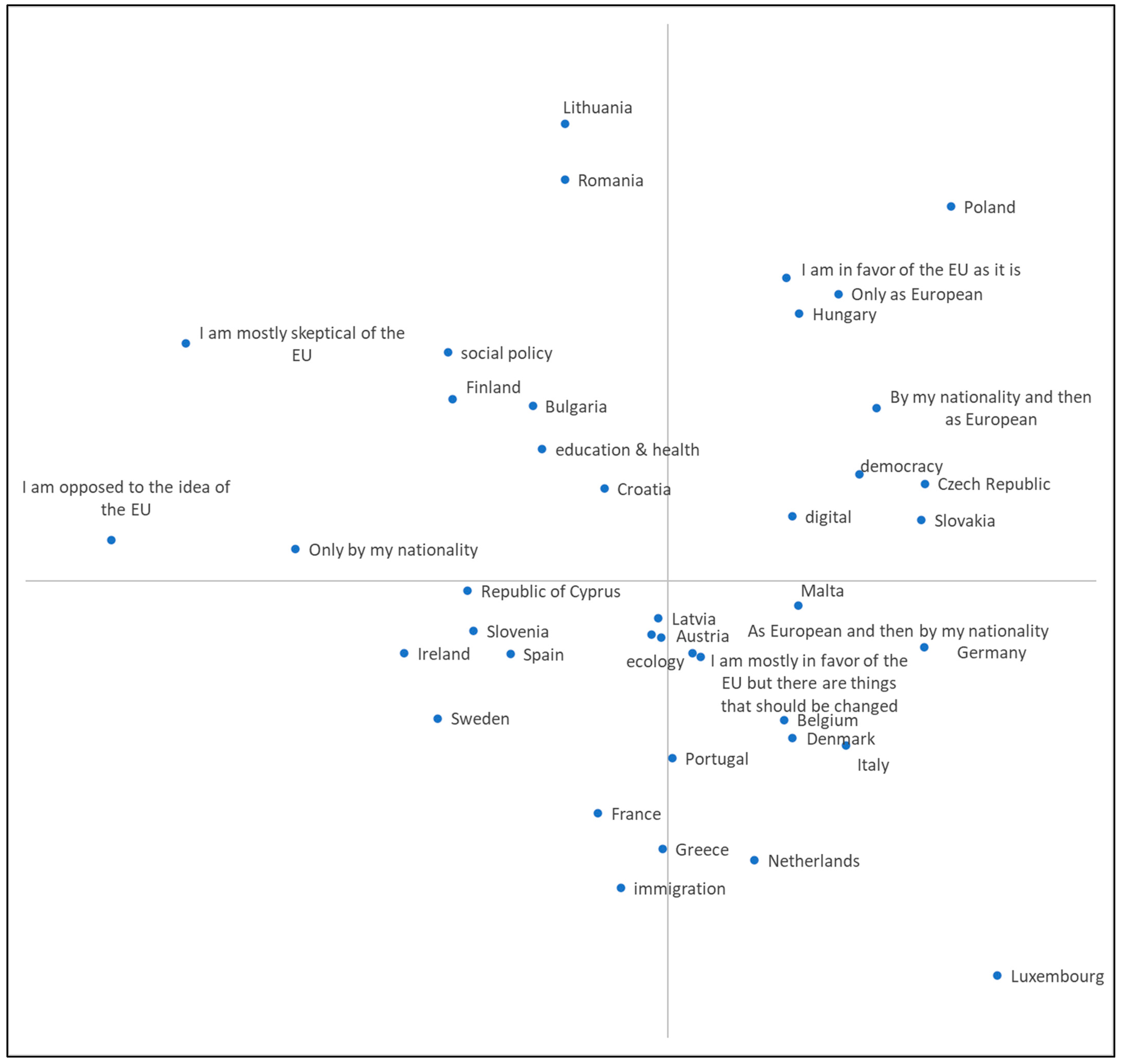

In a second application, a Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) is used to jointly analyze the most important variables of this analysis, to map the various groups of countries not only with reference to issues but also identity and stance towards the EU. MCA positions all items of all the variables in the same dimensions, providing an explanatory map of the phenomenon, bringing together groups of similar objects, highlighting the differences and the polarization between distant objects. The outputs of the analysis, the dimension scores, and the biplot (

Figure 16) are summarized in

Table 2, where the items are categorized into each separate group-quadrant.

The biplot offers a comprehensive view of how different European nations relate to the EU, both in terms of their stance and primary concerns. This visualization segregates the data into four distinct quadrants, which combine national sentiments and policy areas.

The horizontal dimension predominantly underscores a clear polarization between attitudes towards the EU, from opposition on one side to support on the other. In contrast, the vertical axis reflects a divide between socioeconomic challenges and migration issues.

More specifically:

This quadrant features countries largely skeptical or opposed to the EU, primarily focusing on social policies.

Countries: Bulgaria, Croatia, Finland, Lithuania, and Romania.

EU Stances: Mainly skeptical or opposed.

Priority issue: Social policy.

These countries, primarily Eastern and Northern European, have historically been more guarded about their sovereignty. Their skepticism might arise from concerns about the EU’s impact on domestic social policies or perceived impositions on their national policies. Their focus on social policy could also indicate internal challenges related to welfare, healthcare, or education, which they might perceive as being impacted by broader EU directives.

- (2)

Upper Right Quadrant:

Nations here demonstrate a balance between national identity and a broader European identity. Their concerns revolve around democracy and digital transformation.

Countries: Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia.

EU Stances: Generally favorable.

Priority issue: Democracy and digital transformation.

These Central European nations have witnessed significant economic growth and development in recent decades. While they maintain a strong sense of national identity, they also acknowledge the benefits of EU membership. Their emphasis on democracy suggests that there is an internal discourse around governance, possibly tied to EU values. The focus on digital transformation might be due to their rapid technological advancement and the need to integrate seamlessly into the European digital economy.

- (3)

Bottom Left Quadrant:

Nations here lean more European in identity but express reservations about certain EU policies. The dichotomy of concerns—ecology versus migration—is evident.

Countries: Austria, the Republic of Cyprus, France, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden.

Priority issues: Ecology and migration.

These countries, spread across Western, Southern, and Northern Europe, have deep-seated ties to the EU project. Their concern about ecology, especially in the pro-EU camp, signifies a commitment to environmental sustainability—a cornerstone of modern EU policy. In contrast, the emphasis on migration, especially among the skeptics, could be linked to recent migration crises and debates on multiculturalism, integration, and national identity.

- (4)

Bottom Right Quadrant:

This space encapsulates nations with strong support for the EU, but with suggestions for refinement.

Countries: Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, and Portugal.

Priority issue: Broadly supportive, with calls for specific changes.

These Western European nations are foundational EU members or have been deeply integrated for decades. Their robust support for the EU could stem from the tangible benefits they’ve experienced, from economic growth to geopolitical stability. However, their call for changes reflects a mature relationship with the EU—supporting its core while advocating for its evolution.

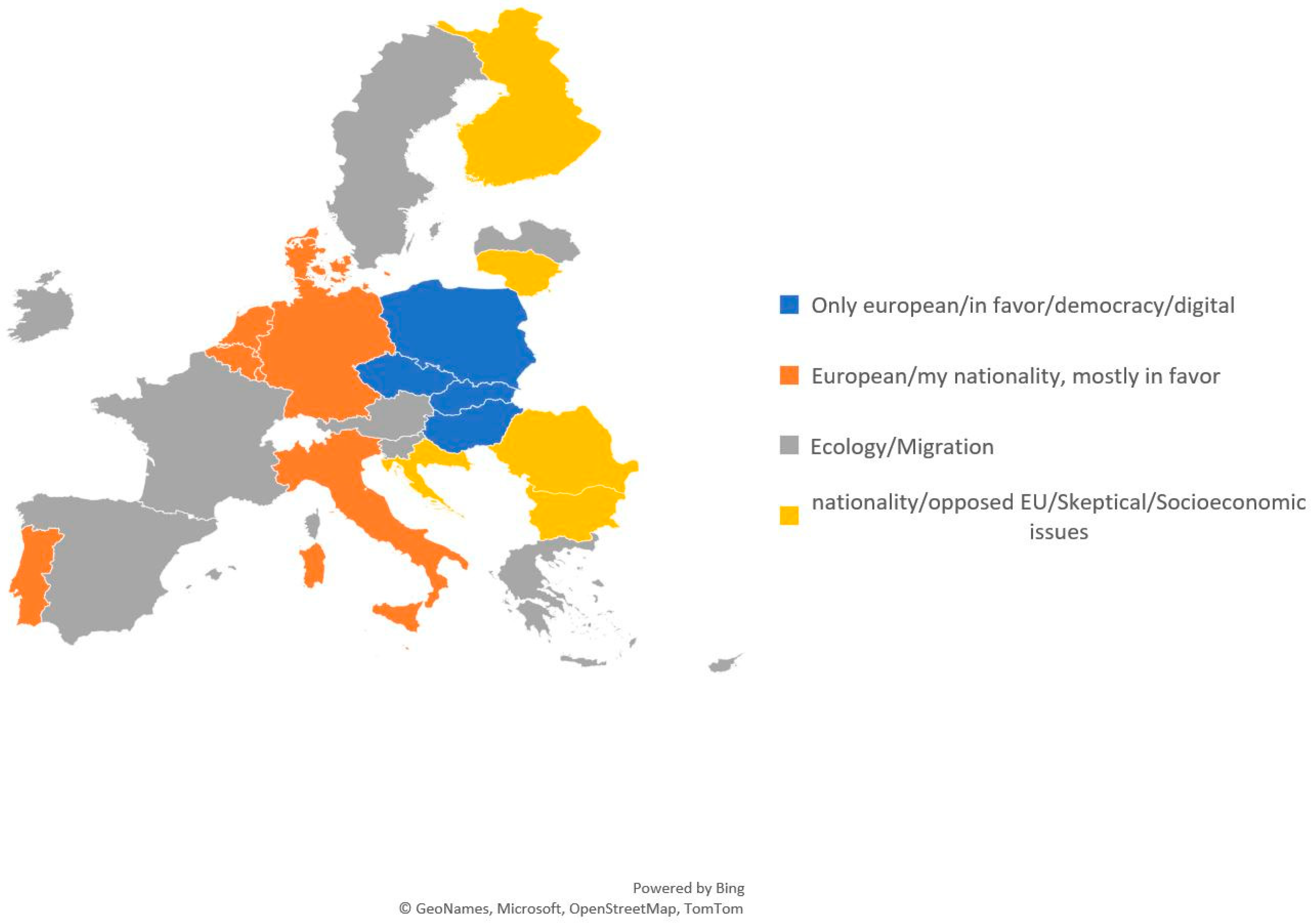

Overall, the MCA map visualizes a Europe of diverse sentiments (

Figure 17), revealing a tapestry of EU relationships influenced by unique socioeconomic and migration challenges. These groupings suggest that while historical, cultural, and economic factors play a significant role in shaping national EU stances, contemporary issues like digital transformation, ecology, and migration are becoming pivotal in national discourses.

6. Discussion

This study sets out to explore how socio-demographic characteristics and national backgrounds shape young Europeans’ attitudes toward key policy issues and the European Union (EU) itself. Overall, the results revealed a broad but conditional support for the EU: while most young people expressed favorable views, they also voiced concerns about limited inclusion in decision-making processes and a perception that the EU lacks responsiveness due to national-level vetoes and fragmented governance. These findings echo earlier observations in the literature that youth are both hopeful and skeptical actors in the European project [

7,

17].

Using correspondence analysis, youth priorities were clustered into six thematic categories: (1) Democracy and Rule of Law, (2) Climate, (3) Migration, (4) Economy, Jobs, and Social Justice, (5) Digital Transformation, and (6) Education and Health. Moreover, these were aligned with identity, demographic factors, and national context. A key insight was that young people who identified primarily as “European” were more likely to support the EU and prioritize issues like democracy and digital transformation. Conversely, those with a stronger national identity expressed skepticism, particularly when focused on economic justice and migration, findings in line with broader scholarship on identity and integration [

10,

32].

Demographic factors played an important role in issue prioritization. Women tended to focus on migration and education/health, while men leaned toward economic concerns and digital transformation. Younger respondents (15–21) emphasized climate and digital issues, reflecting future-oriented concerns, whereas those aged 22–29 prioritized economic and social justice issues, likely due to their immediate life stage. These trends reinforce the generational cleavage noted in previous studies on youth and politics [

5,

8].

Geographical residence also emerged as a salient differentiator. Urban and capital-area residents were more supportive of the EU and aligned with democracy and climate concerns. Rural youth, however, prioritized migration and social justice and were more nationally oriented in identity. This urban–rural divide, seen across Europe, mirrors structural political cleavages noted in comparative EU research [

33,

35].

Cross-national analysis further highlighted divergent youth perspectives shaped by national contexts. Young people from Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands displayed strong pro-EU sentiments and prioritized democratic and digital themes. In contrast, youth from Romania and Bulgaria expressed economic and social concerns while showing weaker identification with Europe. Mediterranean countries (e.g., Greece, Italy, France), facing ongoing migration pressures, emphasized that issue more heavily, consistent with findings from European migration studies [

24,

34]. Climate-focused youth responses were more common in Ireland, Spain, and Finland.

These findings confirm that European identity and EU support are not uniform across the continent. Instead, they are mediated by local socio-economic and political contexts and shaped by the lived realities of inequality, geography, and national political discourse. The analysis also reaffirms that identity remains a core explanatory factor in understanding youth attitudes toward European integration [

2,

25].

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the sampling method. The survey was open and conducted online, allowing broad youth participation but not yielding a representative sample. Future studies should consider stratified sampling or quota-based recruitment to enhance representativeness and enable generalization. Moreover, the data reflect sentiments from mid-2021, after the pandemic but prior to the war in Ukraine and recent shifts in European politics. Hence, these results must be viewed as a temporal snapshot.