Deprivations and Multidimensional Poverty

An examination of scholarly works on the multidimensional approach to poverty shows that the understanding of household deprivation has gradually taken shape, drawing on various conceptual and theoretical perspectives. Contemporary researchers increasingly emphasize not only income indicators but also a broader set of factors that define the level and nature of poverty [

21,

22].

First, it is important to note the contributions of researchers who have expanded the traditional understanding of poverty, viewing it not only as an absolute lack of resources but also in relative terms, considering social standards and the context of the environment [

23]. On this theoretical basis, a more in-depth scientific discussion was developed, in which it became clear that analyzing income alone is insufficient to assess the full range of life opportunities that are important to a person [

24]. This approach emphasizes the importance of components of well-being, such as education, health, and social inclusion [

25]. Consequently, the modern research community is increasingly turning to comprehensive models that combine various forms of deprivation to identify overall vulnerability [

5].

Subsequent progress in this field is linked to the formalization of measurement tools that capture not only the incidence but also the intensity of multiple disadvantages, enabling researchers to examine how various indicators overlap or reinforce one another [

26]. By identifying when and how deprivations compound, whether in terms of housing conditions, education, or healthcare, policymakers can gain a more accurate understanding of how vulnerability forms and persists [

27]. In this way, early conceptual foundations, along with more recent contributions, paved the way for an expanded theoretical and methodological scope in studying multidimensional poverty and household vulnerability [

28].

Over time, the research community has increasingly sought to understand the structure of multidimensional deprivation because mere recognition of their existence does not fully explain how they interrelate or affect one another [

29]. Modern studies convincingly show that a stable income alone does not guarantee a household’s well-being when significant barriers to education, healthcare, and basic infrastructure remain [

30]. For this reason, researchers have described and empirically tested different forms of deprivation to understand how they reinforce one another [

31,

32,

33].

Researchers are increasingly viewing poverty not just as a lack of money but as a complex and multidimensional experience. These can include emotional struggles, limited access to education, moral and social exclusion, and a lack of cultural belonging [

34]. These challenges often make it difficult for people to find work, receive public support, or fully participate in community life. Studies have also shown that being cut off from cultural and social opportunities plays a significant role in making households more vulnerable [

35,

36]. To address such issues of sociocultural deprivation, social innovations are proposed that promote collective empowerment and community development through local initiatives that address deficits in autonomy and opportunity [

37].

Another is educational deprivation, which occurs when children or adults are unable to obtain a quality education due to a lack of schools, unqualified teachers, or financial barriers, and is also among the most critical dimensions of vulnerability [

24]. Limited access to education not only reduces a person’s competitiveness in the labor market but also increases the risk of long-term poverty [

22]. Furthermore, a study examined the impact of vertical educational mismatches on inclusive economic growth, showing that such mismatches, both over- and under-education, are associated with societal-level deprivation and vary across occupational groups, thereby highlighting the importance of educational equalization for equitable development [

38]. Another study highlights how the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated educational and socio-cultural deprivation among vulnerable groups of students, revealing differentiated teacher responses, ranging from passive to proactive, that underscore the need for inclusive, culturally responsive educational practices and targeted teacher training [

39].

Furthermore, one study highlights that rural poverty in eastern India has both economic and sociocultural roots, showing how multidimensional deprivation, particularly in health, education, and living standards, requires comprehensive, localized strategies to effectively address the structural and cultural aspects of exclusion [

40]. In general, health deprivation often arises from the inaccessibility of medical services, which worsens the socioeconomic position of the population [

41].

Another focus area in the literature is that food insecurity affects every age group, weakening the immune system and reducing mental and physical performance. Households experiencing food insecurity are particularly susceptible to price volatility and economic shocks [

42].

Finally, infrastructural deprivation, such as a lack of clean water, reliable electricity, usable roads, and communication networks, imposes a substantial burden on everyday life [

42]. When roads are poor or public utilities are lacking, access to education, healthcare, and job markets is severely compromised [

43]. These deprivations are intertwined, forming “poverty traps,” in which one shortfall leads to another.

In summary, analyzing household deprivation through a multidimensional lens reveals important issues that are often overlooked by income-based approaches alone. When poverty is measured only by income or a single social indicator, the key drivers of inequality may go unnoticed. Factors such as education, healthcare, infrastructure, housing, and social support are deeply interrelated. Understanding this complexity provides a more accurate view of household vulnerability and helps identify areas where policy interventions can be most effective. Using a broader set of indicators, ranging from living conditions to access to social networks, makes it possible to identify weak points in support systems and allocate resources more strategically for long-term impact.

Studying multidimensional poverty is not just an academic task; it also involves practical decisions regarding the design and implementation of support systems. Government institutions, businesses, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and local communities all play important roles, not only as service providers but also as influential actors shaping the everyday life of households. Some researchers stress that efforts to reduce multidimensional poverty must be built on inclusive participation and guided by ethical and economic principles [

36].

Based on these insights, effectively addressing multidimensional deprivation requires identifying the most pressing needs of households and determining how different stakeholders, governments, private sector actors, civil society, and households themselves can collaborate. A coordinated, transparent, and fair distribution of responsibilities among these actors ensures that support measures are relevant and sustainable.

Building on the discussion above, it is essential to connect the theoretical understanding of multidimensional deprivation with practical strategies for stakeholder collaboration [

44]. A growing body of research shows that viewing household poverty and vulnerability through a multidimensional lens reveals complex links between economic, social, and infrastructural factors. By examining a broad set of indicators, such as living conditions, access to education, social support systems, and environmental constraints, researchers and policymakers can more accurately identify critical problem areas and make better decisions regarding resource allocation [

44].

Recent studies on Kazakhstan contribute to this expanding literature by highlighting the regional aspects of multidimensional poverty. They reveal significant spatial inequalities in poverty levels, which are closely tied to factors such as income, income inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient), unemployment, and household size [

45,

46]. These findings emphasize the need for data-driven strategies that address both the economic and structural dimensions of poverty in the region.

One study using advanced spatial econometric models has shown that Kazakhstan’s 16 regions experience persistent spatial inequality. This demonstrates that regional economic outcomes, measured by gross regional product (GRP) per capita, are shaped not only by internal factors (such as unemployment and public spending) but also by spillover effects from neighboring regions. This reinforces the importance of spatially informed policymaking and the need for regional poverty reduction strategies that consider both local and cross-regional dynamics [

47].

Another study focusing on real household income in Kazakhstan found that income levels are significantly affected by nominal income, inflation, economic growth, and the development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), access to credit, and the expansion of non-primary exports. These results highlight the importance of comprehensive economic policies that encourage business development and support inclusive and sustainable income growth [

48].

The reviewed literature highlights the key types of deprivation that shape the multidimensional nature of poverty: limited access to essential goods and services, healthcare, education, transport and communication infrastructure, and cultural and leisure opportunities. These forms of deprivation reflect both material and non-material barriers that constrain households’ well-being and social participation. While access to goods, healthcare, and education directly affect basic living standards and human capital, infrastructural and sociocultural deprivations reinforce spatial and symbolic exclusion, often deepening existing inequalities. Taken together, these dimensions provide a more comprehensive understanding of household vulnerability and inform the development of integrated and targeted policy responses (

Table 1).

The scholarly discourse reinforces the notion that measuring poverty along multiple dimensions is the most reliable way to identify specific vulnerabilities often hidden by a strictly income-based focus. Recognizing the varied roles and interests of diverse stakeholders paves the way for more collaborative and transparent support strategies that align with local needs. By viewing social policy interventions in such an integrated manner, researchers and practitioners are better positioned to close the gaps created by fragmented measures and deliver measurable improvements in the quality of life of those most at risk.

The research gap lies in the fact that existing studies on poverty in Kazakhstan are dominated by one-dimensional (primarily income-based) indicators, while the cumulative and intersecting effects of various forms of deprivation, educational, medical, infrastructural, socio-cultural, and child-related, on household vulnerability remain insufficiently explored. There is a lack of regionally disaggregated empirical data based on household surveys, which hinders the identification of latent deprivation structures and the development of spatially sensitive social-policy strategies.

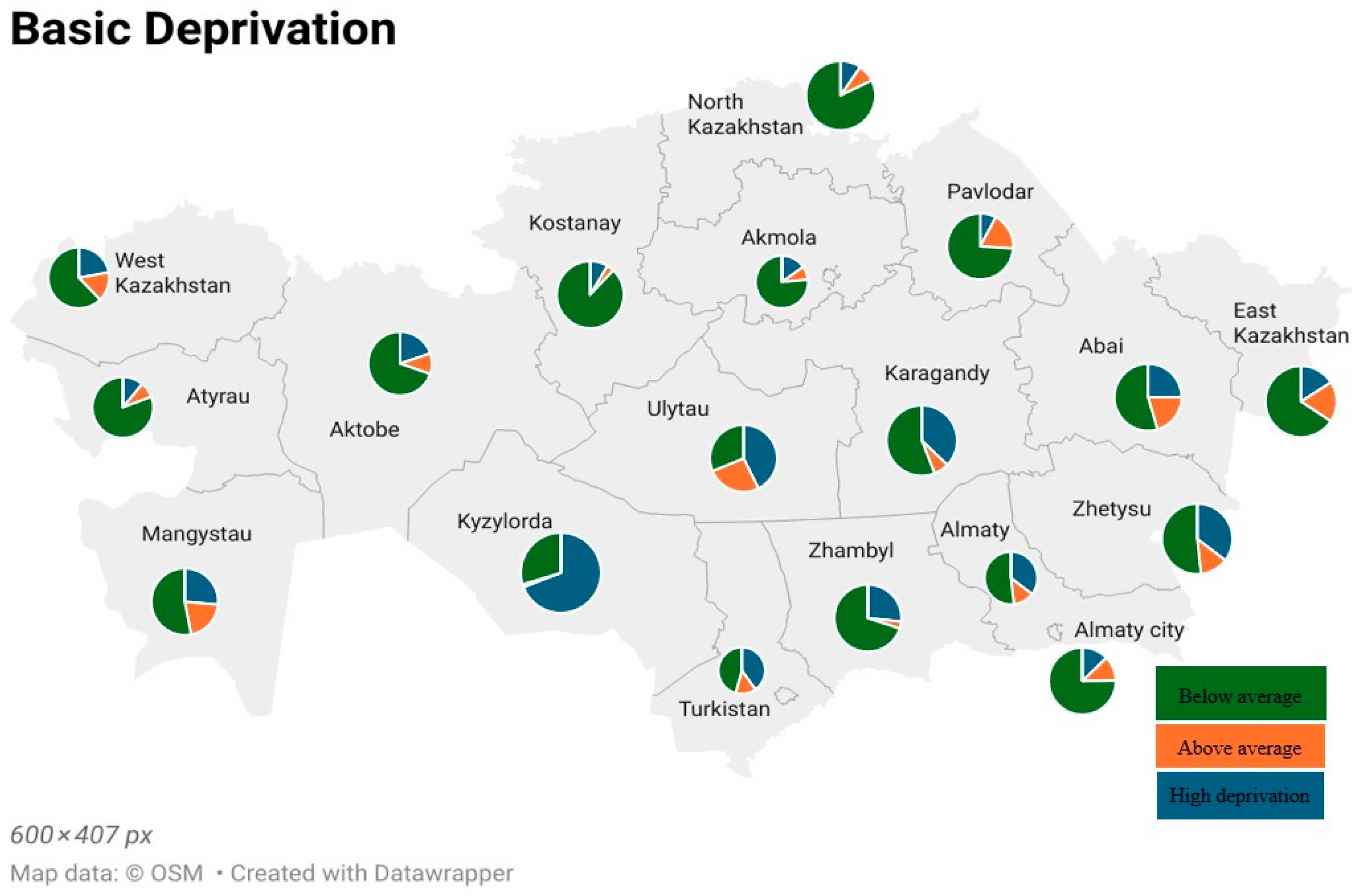

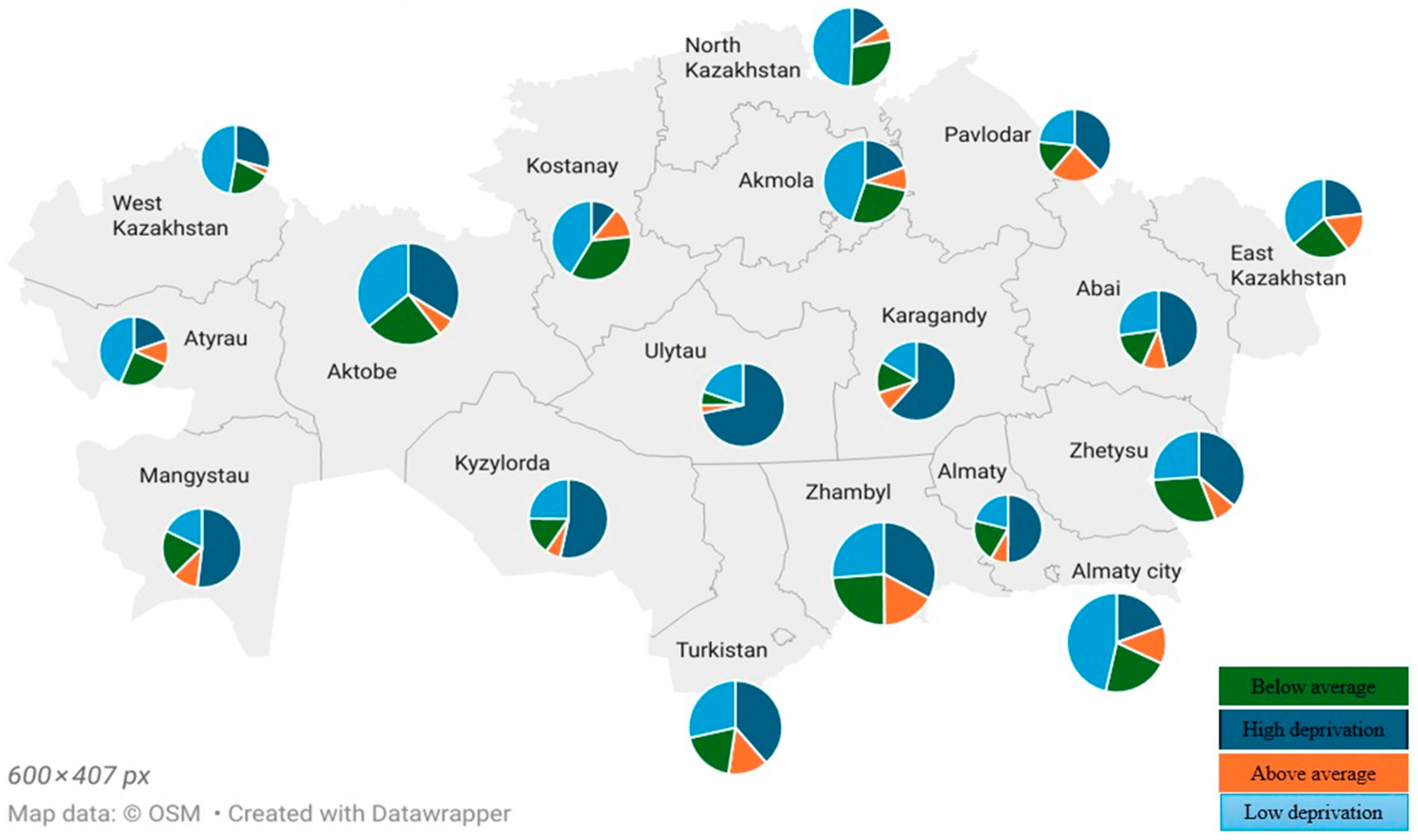

Building on the reviewed literature, this study formulates two central research questions: What are the key latent dimensions of multidimensional household deprivation in Kazakhstan, and what cumulative effects do they exert on household vulnerability? How do the levels and structures of basic and socio-cultural deprivation vary across different regions of Kazakhstan?

To address these questions, two hypotheses are proposed.

H1. High levels of basic deprivation (food security and children’s basic needs) are statistically positively correlated with high levels of socio-cultural deprivation, thereby reinforcing overall household vulnerability.

H2. Southern and western regions of Kazakhstan exhibit significantly higher levels of both basic and socio-cultural deprivation compared to northern and central regions.