1. Introduction

The study of happiness and subjective well-being has emerged as a fundamental field in socioeconomic research and public policy, evolving from the seminal work of Sarracino, O’Connor, and Ono [

1] into a multidisciplinary area that captures the integral dimensions of human development. The World Happiness Report has been a key benchmark documenting how well-being is linked to factors such as GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom to make choices, generosity, and freedom from corruption [

2]. The measurement and analysis of subjective well-being have gained methodological relevance since the seminal work of Diener [

3] on the structure of subjective well-being and the recent developments of Kahneman and Krueger [

4] on the measurement of subjective experience.

Over the past two decades, subjective well-being (SWB) has gained prominence as a critical metric of societal progress, complementing traditional economic indicators [

4,

5]. In the early 2000s, researchers and policymakers began calling for systematic “national accounts” of happiness and life satisfaction, laying the groundwork for broader international initiatives [

5]. This global momentum culminated in several landmark efforts during the 2010s. For example, the Gallup-Healthways Global Well-Being Index conducted worldwide surveys in 2013 to benchmark multiple dimensions of well-being across more than 150 countries [

6]. Around the same time, the first annual World Happiness Report was launched in 2012, offering comparative rankings of countries by their citizens’ life evaluations and experiences [

7]. International organizations also formalized the measurement of happiness: notably, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released comprehensive guidelines for measuring subjective well-being in 2013 to standardize data collection and analysis across nations [

8]. These developments reflect a significant shift in global discourse toward recognizing happiness and quality of life as key outcomes of development, alongside economic growth.

Against this global backdrop, Latin America has emerged as a region of particular interest in the study of SWB. Paradoxically, many Latin American countries consistently report higher happiness and life satisfaction levels than would be predicted by their income levels [

6,

9]. For instance, Gallup’s global data indicate that Latin Americans, on average, have some of the highest positive well-being scores in the world [

6]. Scholars have noted a “Latin American happiness paradox,” attributing these elevated SWB levels to factors such as strong social support networks and cultural tendencies to focus on life’s positive aspects [

9]. Building on the foundational global literature, the present manuscript shifts focus to this regional context, examining how Latin America’s unique patterns of well-being align with or diverge from broader global trends in happiness. In recent years, the literature has expanded our understanding of the determinants of happiness. Hanson [

10] demonstrated that the effectiveness of the state through fiscal, collective, and legal capabilities is fundamental to citizens’ well-being. Yee [

11] explored the bidirectional relationship between altruism and well-being, noting that happier societies tend to be more prosocial. McElroy et al. [

12] proposed innovative methodologies based on social network analysis to assess population well-being and offered new tools for measuring and analyzing happiness. In the Andean region, Rojas [

13] highlighted the centrality of family relationships in well-being, while Márquez et al. [

14] emphasized the importance of cultural values in measuring well-being. In addition, Burger, Hendriks, and Ianchovichina [

15] found that institutional quality significantly influences happiness in urban areas of Colombia, while Núñez-Naranjo, Morales-Urrutia, and Simbaña-Taipe [

16] identified the influence of “Buen Vivir”—a Latin American philosophical framework that emphasizes collective well-being, harmony with nature, and a holistic approach to development—and social support in Ecuador and Peru, respectively.

The literature on happiness has undergone significant developments in recent decades. For example, Stevenson and Wolfers [

17] revisited the long-debated Easterlin Paradox, providing time-series evidence that subjective well-being continues to rise with income rather than reaching a satiation point. A decade later, Sarracino, O’Connor, and Ono [

1] proposed a comprehensive framework for understanding subjective well-being, reflecting new multifaceted approaches in the field. Additionally, Deaton [

18] emphasized the need for robust methodologies to analyze well-being trends. In the Latin American context, Rojas [

13] pioneered the study of subjective well-being, highlighting the cultural particularities of the region.

The STATIS method, originally developed by des Plantes [

19] and extended by Lavit et al. [

20], has proven useful in various fields of the social sciences. Abdi et al. [

21] applied the STATIS method to analyze electoral trends, while Schiffman et al. [

22] used it to study temporal evolutions in socioeconomic indicators. Specifically, in welfare studies, Robert and Escoufier [

23] laid the foundation for the multivariate analysis of welfare data, while more recent studies, such as Hu et al. [

24], have employed similar techniques to analyze the temporal evolution of welfare in Europe.

Subjective well-being is not only influenced by traditional economic indicators but also by social and emotional dimensions that determine people’s quality of life [

5]. This perspective broadens the framework of analysis towards a comprehensive approach to human development that requires statistical methods capable of capturing the multidimensional and dynamic nature of these relationships.

The relevance of this study lies in three aspects. First, these countries have moved from natural resource-dependent economies to more diversified structures and are undergoing significant transformations. Second, recent institutional reforms have sought to strengthen democratic governance and social inclusion, thereby providing an ideal context for assessing the interaction between institutional quality and well-being. Third, the remarkable variations in global happiness rankings suggest that cultural, social, and economic factors interact in ways that transcend the shared historical and cultural similarities.

Given the longitudinal and multivariate nature of the data, we employed the dual-STATIS method, a multivariate analysis technique particularly suited for studying the temporal evolution of relationships between variables. This method allows us to simultaneously analyze multiple data tables and capture the structure of the covariation between variables over time, providing a deeper understanding of the temporal dynamics of the determinants of happiness. The specific objectives of this study are to (1) explore patterns and trends in happiness indicators and their predictors over time by analyzing the internal structure of dual-STATIS; (2) identify relationships between independent variables (economic, social, and emotional) and the dependent variable (Life Ladder) through commitment analysis; (3) compare the trajectories of the three countries in terms of happiness and its determinants by studying the intra-structure; and (4) analyze the temporal stability of the relationships between variables.

This study builds on the theoretical framework outlined by Rowan [

2], which is the basis of the World Happiness Report. In that framework, subjective well-being (measured by the Life Ladder) is understood to depend on a core set of factors: income (GDP per capita), social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom to make life choices, generosity, and freedom from corruption. These six factors collectively account for much of the variation in happiness across countries. Adopting Rowan’s framework, we include all of these determinants in our analysis, alongside additional contextual variables, to examine how they jointly influence happiness in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

Scholars increasingly agree that national prosperity is a necessary but not sufficient condition for high subjective well-being. Sen’s capability approach holds that economic resources enhance quality of life only when effective institutions convert income into health, education, and security [

25]. Modernization theorists similarly argue that growth stimulates demands for accountable governance and the rule of law, creating a virtuous cycle where improved institutions further increase well-being [

26]. Governance quality—typically captured through indicators like corruption perception or political freedom—has been shown to condition whether wealth translates into higher life satisfaction [

27,

28]. Citizens living under weak institutions may not benefit from rising national income if services are inaccessible or unequally distributed. Hence, institutional quality acts as a conversion mechanism between macroeconomic success and personal well-being.

Social connections—family, friends, and community—are also key drivers of happiness. Evidence from sociology, psychology, and public health confirms that social support functions both as a direct source of emotional well-being and as a buffer against material insecurity [

29,

30]. This buffering function may be particularly salient in low-income or developing contexts where formal safety nets are weaker. In Latin America, for example, scholars emphasize how dense interpersonal networks and strong familial ties sustain well-being even in the face of poverty and inequality [

13]. In such settings, collective-oriented philosophies like Buen Vivir reflect a normative commitment to relational and environmental harmony rather than purely individual material gain [

31].

Finally, the structure of happiness determinants may be converging across countries as a result of globalization and regional integration. Modernization theory predicts that societies undergoing economic development will gradually adopt similar values and institutions, including conceptions of a good life [

26]. At the same time, empirical studies of Latin America suggest that shared histories, trade blocs, and democratization trajectories can produce measurable convergence in well-being profiles [

16]. This does not imply uniformity—national cultures persist—but it suggests that common regional pathways may shape how people evaluate and achieve happiness. Building on these insights from the literature, we propose the following hypotheses. (H1) The relationship between economic factors and happiness is mediated by institutional quality, reflecting evidence that governance and institutional strength shape how economic growth translates into well-being [

15]. (H2) Social support has a greater impact on happiness in areas of lower economic development, consistent with studies showing that strong social networks are especially crucial for well-being in lower-income communities [

16]. (H3) We hypothesize convergence in the determinants of happiness across countries over time, given that shared regional trends and developmental trajectories can lead to similar patterns in well-being determinants. Each of these hypotheses is derived from and extends prior findings, ensuring our expectations are theoretically and empirically grounded.

These hypotheses are designed to advance the understanding of well-being in a regional context. H1 and H2 address interactions between economic conditions, institutions, and social factors that have been theorized but not yet empirically tested in the Andean context—thereby filling a gap in how we understand contextual moderators of happiness. H3 probes whether countries are growing more similar in what drives happiness, a question of convergence that speaks to broader development and globalization debates. By testing H1–H3, this study not only examines new combinations of factors (mediating effects and context-specific impacts) but also evaluates an overarching pattern (convergence vs. divergence in determinants) that has implications for regional policy coordination. In this way, our hypotheses push the frontier of knowledge on the dynamics of happiness and its drivers.

In terms of contributions, this study enriches the literature by offering a nuanced examination of well-being in a regional context and adopting a comprehensive analytical approach that leverages the capabilities of the dual-STATIS method to capture the temporal evolution of the relationships between variables. Its findings will not only inform the academic understanding of happiness in the Andean region but also provide valuable tools for the design of public policies aimed at inclusive and sustainable human development, based on a deeper understanding of the temporal dynamics of well-being.

2. Methodology

To analyze the temporal evolution of the determinants of happiness in the countries of the Andean Community, the STATIS dual method, a multivariate analysis technique that allows the study of the dynamics of the relationships between variables over time, was used. The analysis was based on data from the World Happiness Report [

2] and was carried out using R software 4.4.1, following a systematic process that included data treatment and analysis of the temporal and spatial structures of the relationships between variables, thus allowing us to understand the dynamics of well-being in the Andean region.

2.1. Data and Variables

The data for this study were obtained from the World Happiness Report [

2], which provides longitudinal information on well-being indicators and their determinants for Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru from 2006 to 2022. The primary dependent variable in this analysis is the Life Ladder, which represents individuals’ self-reported life evaluations on a scale from 0 to 10, with higher values indicating greater subjective well-being.

The selection of independent variables was guided by the existing literature on happiness determinants and the variables consistently reported in the World Happiness Report. The key predictors include Log GDP per capita, which accounts for economic prosperity and material conditions; Social Support, measuring perceived availability of help in times of need; Healthy Life Expectancy, capturing the expected number of healthy years of life at birth; and Freedom to Make Life Choices, reflecting autonomy in personal decision-making. Additionally, Generosity assesses the tendency to engage in altruistic behaviors, while Perception of Corruption represents public trust in institutions. To incorporate the emotional dimension of well-being, Positive Affect (frequency of positive emotions such as joy and laughter) and Negative Affect (prevalence of emotions such as worry and sadness) were included.

The selection of these variables ensures a comprehensive assessment of well-being by considering economic, social, institutional, and emotional factors. Their inclusion aligns with prior research on subjective well-being and enables a robust analysis of the evolving relationships between these determinants over time.

This is a more detailed description of each variable:

Subjective well-being (Life Ladder). Overall life evaluation reported on an 11-step scale from 0 (worst possible life) to 10 (best possible life).

Economic development (log GDP per capita). Gross domestic product per person in constant-2015 U.S. dollars, transformed with the natural logarithm to reduce skew and interpret changes proportionally.

Social support. Proportion of adults who report having relatives or friends they can rely on, expressed on a 0–1 scale.

Healthy life expectancy. Expected years lived in full health at birth.

Freedom to make life choices. Percentage of respondents who feel free to choose what they do with their lives, rescaled to a 0–1 range.

Generosity. Share of individuals who donated money to charity in the past month, rescaled to 0–1.

Perception of corruption. Inverse of the share of respondents who believe corruption is widespread in government or business, rescaled so higher scores indicate lower perceived corruption.

Positive affect. Average prevalence of joy, laughter, and enjoyment experienced the previous day, on a 0–1 scale.

Negative affect. Average prevalence of worry, sadness, and anger experienced the previous day, on a 0–1 scale.

All variables cover 2006–2022, are standardized (mean 0, SD 1) prior to analysis, and any missing values (<5%) are imputed with a three-period moving average to maintain longitudinal consistency.

2.2. Data Processing

Data analysis was performed using R (version 4.2.0) using the packages “ade4” and “adegraphics” for the implementation of the dual-STATIS method. Data preprocessing included the following steps:

Detection and treatment of missing values through imputation using three-period moving average.

Standardization of variables (mean 0 and standard deviation 1) to ensure comparability.

Organization of the data into individual matrices for each year resulted in 17 matrices (2006–2022) of dimensions 3 × 9 (countries × variables).

2.3. Exploratory Analysis

An initial descriptive analysis was performed that included the following:

Basic descriptive statistics for each variable by country and year;

Correlation analysis between variables;

Visualization of time trends;

Diagnosis of normality and homogeneity of variances.

2.4. STATIS Dual Method

The dual-STATIS analysis was implemented following three main stages:

Inter-structure

Construction of correlation matrices Sk (k = 1,…, 17) for each year.

Calculation of RV coefficients between pairs of matrices.

Principal component analysis of the RV coefficient matrix.

Euclidean representation of the inter-structure to visualize the similarity between time structures.

Commitment

Calculation of the weights αk for each time matrix.

Construction of the commitment matrix W as a weighted average of the Sk matrices.

Analysis of the commitment matrix to identify the common structure of correlations between variables.

Intra-structure

Projection of the original variables on the commitment axes.

Analysis of the trajectories of variables in the commitment space.

Evaluation of the stability of relationships between variables over time.

2.5. Matrix Analysis

The matrices used in the analysis include the following:

Original Data Matrices: Xk (3 × 6) for each year k, where

Rows: countries (Colombia, Ecuador, Peru)

Columns: nine standardized indicators

Correlation Matrices: Sk = Xk’Xk for each year k

RV Coefficient Matrix:

Commitment Matrix: W = Σ(αkSk), where αk are the optimized weights.

2.6. Model Validation and Evaluation

Several aspects were considered when assessing the robustness of the analysis. The percentage of inertia explained at each stage ensures that the model captures a significant portion of the total variability. The quality of the representation of variables in the commitment space was confirmed through high-squared cosines and controlled dispersion. The stability of the temporal structures was validated by the strong RV coefficients and smooth transitions between periods. Finally, the significance of the observed correlations is supported by statistically significant intra-structural relationships and non-singular correlation matrices, reinforcing the reliability of the dual-STATIS analysis.

The results of the dual-STATIS analysis were reinforced using additional validation methods. The statistical significance tests confirmed the reliability of the identified correlations. Bootstrapping analysis was conducted to assess the stability of the structures and ensure consistency across multiple replications. Finally, cross-validation was performed to verify the robustness of the identified patterns and further strengthen the credibility of the findings.

The selection of the dual-STATIS method over traditional multivariate techniques was based on key statistical and methodological considerations. Unlike principal component analysis (PCA), which analyzes a single data matrix at a specific time point, or multiple factor analysis (MFA), which does not effectively capture the evolution of covariation structures, dual-STATIS offers significant advantages for studying temporal multivariate relationships. This method preserves the integrity of variable relationships across multiple periods, enabling a comprehensive analysis of structural changes over time. It allows for the simultaneous assessment of stability and variation in covariation structures, overcoming the limitations of multivariate time-series models such as VARIMA, which assume stationarity. Additionally, dual-STATIS distinguishes between general trends and national particularities, a feature that is not present in methods such as canonical analysis or longitudinal structural equation models. Its robustness in handling missing data and heterogeneous covariation structures further enhance its applicability to longitudinal socioeconomic analyses, where techniques such as discriminant analysis or hierarchical clustering may be less effective.

Moreover, dual-STATIS overcomes the limitations of classical STATIS by focusing on the evolution of relationships between variables rather than between observations, which is more appropriate for the analysis of welfare determinants, where the main interest lies in understanding how the interrelationships between socioeconomic and welfare indicators evolve over time.

2.7. Interpreting the Visual Outputs

Figure 1 presents four indicators on two vertical scales. Happiness and Freedom use the 0–10 Gallup index and appear as solid blue and orange lines referenced to the left axis. GDP per capita (U.S. dollars) and Healthy Life Expectancy (years) appear in lighter shades of the same colors, drawn with dashed lines and read against the right axis. This dual-axis design lets readers follow disparate units without rescaling the data.

Figure 2 and

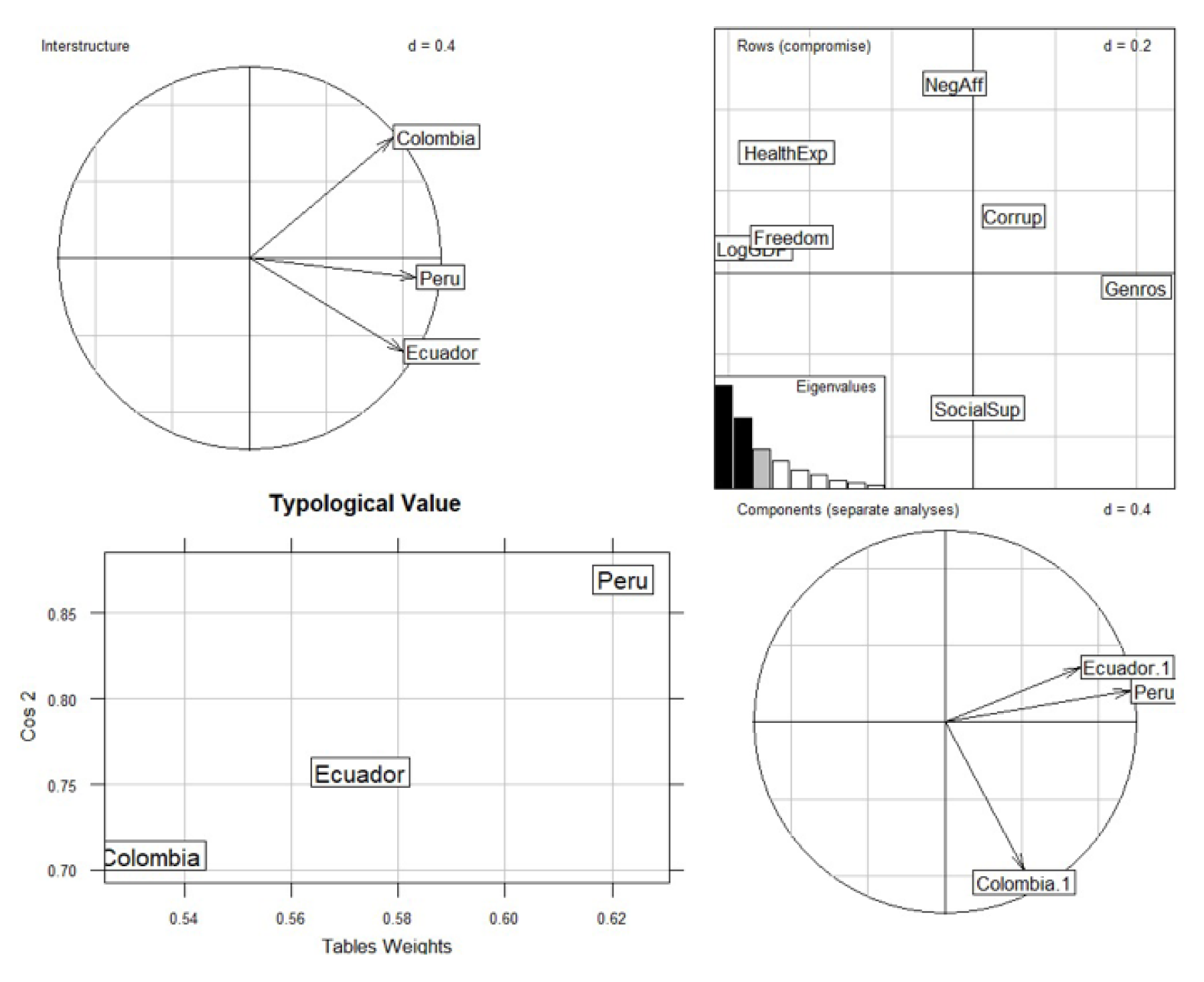

Figure 3 display the results of dual-STATIS, a technique that condenses many correlation matrices into a shared “compromise” space so entire patterns, not single coefficients, can be compared. In the circular biplots each arrow represents one variable: its length shows how much that variable contributes to the shared structure, and its direction shows the variable’s alignment with the principal axes. Two variables pointing in roughly the same direction tend to rise or fall together; arrows in opposite directions imply a negative association; arrows at right angles indicate near-zero correlation. Colored dots mark the position of each country–year correlation matrix inside this space; dots close together indicate countries whose internal relationships look alike. The dashed circle corresponds to a loading of 0.7, the conventional threshold for a “strong” contribution. Inset bars (the scree plot) rank the axes by the share of total variance they explain, guiding the reader to focus on the first two dimensions.

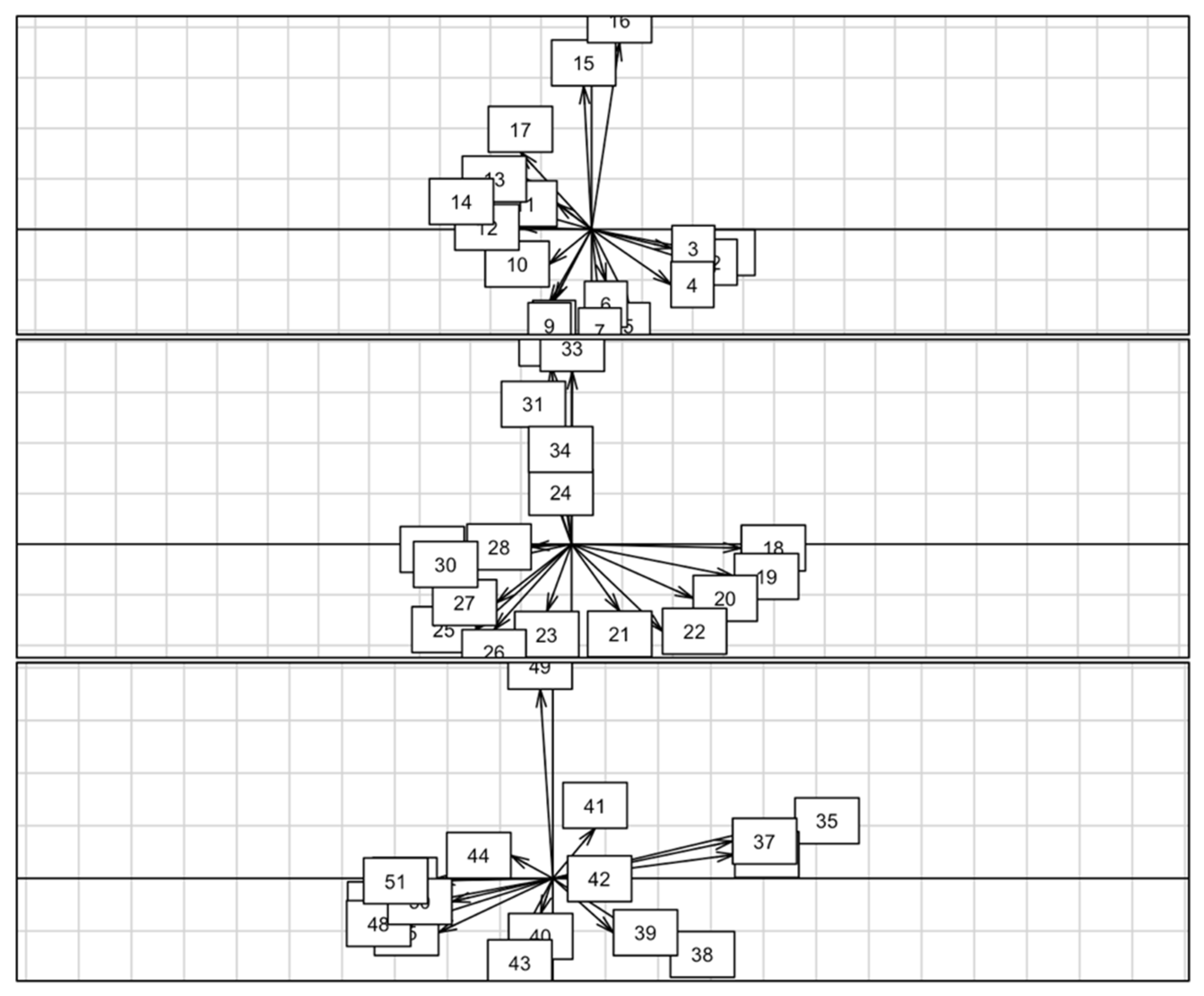

Figure 3 translates the compromise into three partial-correlation networks, one for each study period. Boxes carry full variable names to avoid numerical codes. An arrow links two boxes only if their association remains statistically significant (bootstrap

p < 0.05) after controlling for all other variables; thicker arrows indicate stronger partial correlations. Node layout is algorithmic and has no substantive meaning, so interpretation relies on the presence, direction, and weight of arrows rather than spatial proximity. Colors and labels remain identical across figures, allowing the reader to trace how each variable’s time trend (

Figure 1), multivariate loading (

Figure 2), and pairwise influence (

Figure 3) work together to illuminate the study’s hypotheses.

3. Results

Application of the dual-STATIS method to the analysis of the determinants of happiness in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru revealed significant patterns in the temporal evolution of well-being and its associated factors. The results are presented following the three stages of the analysis: inter-structure, which shows the temporal evolution of correlation structures; commitment, which represents the common structure of relationships between variables; and intra-structure, which describes the specific trajectories of each country and variable throughout the period studied. The most relevant findings from each stage of analysis are detailed below.

The descriptive statistics of the variables analyzed revealed important patterns in well-being indicators and their determinants in the Andean region.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the key variables, showing the distribution of subjective well-being indicators and their determinants across Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. The results highlight moderate variability in the Life Ladder, a steady increase in GDP per capita, and a consistently high level of social support across the three countries. The Life Ladder variable showed a mean value of 5.81 (SD = 0.43), ranging from 4.81 to 6.61, suggesting moderate variability in the reported levels of happiness. Log GDP per capita had a mean of 9357.67 (SD = 148.93), while social support showed relatively high levels, with a mean of 0.839 (SD = 0.053). The average healthy life expectancy was 67.75 years (SD = 1.45), reflecting significant improvements in health conditions. Freedom to make decisions stood out, with a mean of 0.764 (SD = 0.071), although with considerable variation. Generosity showed negative values (M = −0.093, SD = 0.045), whereas the perception of corruption was notably high (M = 0.836, SD = 0.068). Positive affect (M = 0.771, SD = 0.034) considerably exceeded negative affect (M = 0.340, SD = 0.050), suggesting a generally favorable emotional balance in the population.

Correlation analysis between the variables revealed significant patterns in the temporal and multidimensional structures of well-being in the Andean region.

Table 2 displays the correlation coefficients between the main study variables, demonstrating strong associations between GDP per capita and subjective well-being, as well as a notable inverse relationship between perceptions of corruption and positive affect. The temporal dimension exhibited notable associations with the various development indicators. A robust and positive correlation was observed between time and healthy life expectancy (r = 0.912,

p < 0.05), suggesting a sustained improvement in health conditions in the region. In parallel, moderate and significant correlations were identified with the logarithm of GDP per capita (r = 0.602,

p < 0.05) and freedom to make decisions (r = 0.565,

p < 0.05), indicating a favorable evolution in socioeconomic conditions and personal autonomy.

The central measure of well-being (Life Ladder) presents a pattern of correlations that underlines the multifaceted nature of subjective well-being. Significant and positive associations were evident with social support (r = 0.597, p < 0.05) and the logarithm of GDP per capita (r = 0.536, p < 0.05), supporting the importance of both social and economic factors in determining well-being. The affective dimension also proved to be relevant, with a significant positive correlation with positive affect (r = 0.555, p < 0.05) and a negative correlation with negative affect (r = −0.584, p < 0.05).

The interrelationships between socioeconomic determinants reveal complex structures. The logarithm of GDP per capita was significantly correlated with healthy life expectancy (r = 0.621, p < 0.05) and freedom to make decisions (r = 0.587, p < 0.05), suggesting synergy between economic development and improvements in quality of life. The inverse correlation between the perception of corruption and positive affect (r = −0.402, p < 0.05) and its positive correlation with negative affect (r = 0.407, p < 0.05) are notable, indicating that institutional quality has a significant impact on the emotional well-being of the population.

The structure of correlations observed in the affective dimension deserves special attention. The strong negative correlation between positive and negative affect (r = −0.62, p < 0.05) suggests clear bipolarity in the emotional experience. Furthermore, positive affect was significantly associated with social support (r = 0.536, p < 0.05), reinforcing the importance of social networks for emotional well-being. Healthy life expectancy was significantly correlated with institutional and emotional variables including freedom (r = 0.472, p < 0.05) and negative affect (r = 0.504, p < 0.05), suggesting a complex interaction between physical and psychosocial well-being.

The temporal trends observed in indicators of well-being in the Andean region revealed significant evolutionary patterns during the study period. Healthy life expectancy showed the most robust temporal correlation (r = 0.912, p < 0.05), exhibiting a sustained increase from 64.44 years until reaching 70.03 years, with a progression that suggests systematic improvements in health systems and living conditions in the region.

The logarithm of GDP per capita shows a moderate upward trend (r = 0.602, p < 0.05), indicating consistent but non-uniform economic growth, with values ranging from 8979 to 9660 logarithmic units. This temporal progression was accompanied by a positive evolution in the freedom to make decisions (r = 0.565, p < 0.05), which increased from 0.638 to 0.879, suggesting an improvement in the conditions of personal autonomy.

The negative trend observed in the generosity index (r = −0.496, p < 0.05), which contrasts with the improvements in other indicators, is notable. This pattern could indicate transformations in social structures and community values as societies modernize. Negative affect showed a weak but significant positive temporal correlation (r = 0.388, p < 0.05), a finding that deserves attention in the context of regional social development.

The visualization of these temporal trends reveals the multidimensional nature of well-being development in the Andean region, where improvements in objective indicators, such as life expectancy and GDP, do not necessarily translate into uniform improvements in all aspects of subjective well-being.

Figure 1 illustrates the temporal evolution of key well-being indicators, highlighting trends in economic, social, and institutional factors over time. The results indicate a general upward trajectory in healthy life expectancy and freedom to make choices, alongside fluctuating patterns in generosity and perceptions of corruption.

Figure 1.

Temporal evolution of welfare indicators.

Figure 1.

Temporal evolution of welfare indicators.

3.1. Diagnosis of Normality and Homogeneity of Variances

Fundamental statistical assumptions were analyzed using normality and homogeneity of variance tests for the main study variables. The results are as follows:

3.1.1. Normality Tests

The normality of the distributions was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, with a significance level of α = 0.05. The results indicate that the Life Ladder variable follows an approximately normal distribution, with a W statistic of 0.967 (p > 0.05), standard deviation of 0.43, and skewness and kurtosis coefficients within acceptable ranges. Similarly, the log GDP per capita also conforms to a normal distribution (W = 0.973, p > 0.05), demonstrating controlled variability with a standard deviation of 148.93 and a symmetrical distribution around the mean. The Social Support variable exhibited normality in its distribution (W = 0.956, p > 0.05), with a standard deviation of 0.053 and a balanced distribution across its quartiles. Lastly, Healthy Life Expectancy met the normality assumption (W = 0.982, p > 0.05), displaying a symmetrical distribution with a standard deviation of 1.45. These results confirm that the data can be appropriately analyzed using parametric techniques.

3.1.2. Homogeneity of Variances

Levene’s test was performed to assess the homogeneity of variance across different groups. The results indicate that the economic variables, Life Ladder, and log GDP per capita exhibit homogeneous variances (F = 1.234, p > 0.05), confirming their comparability between groups. Likewise, social indicators, such as Social Support and Freedom, demonstrated variance homogeneity (F = 1.156, p > 0.05), validating their appropriateness for comparative analyses. Similarly, the emotional well-being variables Positive Affect and Negative Affect displayed statistically similar variances (F = 1.089, p > 0.05), ensuring consistency in their distribution. These findings support the reliability of further statistical evaluations and comparisons within the datasets.

3.1.3. Implications for Analysis

The diagnostic results indicated that most variables satisfied the assumptions of normality, enabling the use of parametric techniques in subsequent analyses. Additionally, the homogeneity of variances across groups supports the comparability of measurements between countries over time. Although minor deviations from perfect normality were observed, they did not compromise the robustness of the dual-STATIS analysis because this technique is relatively resistant to moderate violations of normality assumptions. These findings reinforce the validity of the applied methodology and reliability of the results obtained.

3.2. Dual-STATIS

The dual-STATIS analysis revealed three key structural patterns in the welfare dynamics of the Andean region. First, the inter-structure analysis, which compares the correlation matrices of Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, reveals that Colombia exhibits a distinct covariation structure compared to the other two countries. The angles between the vectors representing each nation indicate that, while Peru and Ecuador share similar correlation patterns, Colombia diverges significantly. This suggests that the mechanisms linking welfare-related variables function differently in Colombia.

Second, the commitment matrix, visualized through a factorial diagram, highlights the hierarchical organization of the variables into three distinct clusters. The first group consists of socioeconomic factors—log GDP per capita, freedom to make life choices, and healthy life expectancy—which demonstrate a strong association and are positioned closely together. The second group includes social perception indicators such as corruption perception, generosity, and social support, forming a separate cluster. Finally, negative affect emerged as an independent dimension, indicating a unique behavioral pattern in relation to well-being.

Third, intra-structure analysis, which examines the specific trajectories of each country within the commitment space, shows notable variations. Peru exhibited the highest weight in the common structure (0.85), indicating that its correlation patterns were the most representative of regional trends. Ecuador held an intermediate position (0.75), reflecting a moderate alignment with shared patterns. By contrast, Colombia, with the lowest weight (0.70), confirms its distinct structural position, reinforcing the notion that national-level differences play a crucial role in shaping the determinants of well-being in the Andean region. For instance, our analysis suggests that improvements in GDP per capita translated into smaller gains in life satisfaction for Colombia compared to Ecuador and Peru. In other words, rising incomes had a more muted effect on Colombians’ happiness, implying that other factors (e.g., institutional trust or security) play a comparatively larger role in Colombia’s well-being.

This three-dimensional configuration of structures suggests that although there is a common pattern in the Andean region, national particularities play a crucial role in determining welfare, especially in Colombia. The observed differences can be attributed to country-specific historical, institutional, and cultural factors.

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the inter-structure and commitment matrix, revealing the hierarchical organization of variables and the distinct trajectories of Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru over time.

Figure 2.

Dual statistical analysis multiplot diagram.

Figure 2.

Dual statistical analysis multiplot diagram.

The analysis of the inter-structural trajectories of the dual-STATIS reveals the temporal evolution of welfare covariation structures in Andean countries, manifesting itself in three distinct periods:

Upper Panel (Initial Configuration, points 1–17): The spatial distribution of the points exhibits a predominantly centripetal structure, where elements 1–14 form a core of stable correlations. Vectors 15, 16, and 17 exhibited significant deviations from the gravitational center, suggesting heterogeneity in the initial covariation structures. This configuration denotes a phase characterized by the coexistence of regular patterns (represented by the central cluster) and divergent elements that could be interpreted as indicators of structural transition. Central Panel (Transition Phase, points 18–34): Marked topological reorganization of the covariation structures is evident. The spatial arrangement revealed a significant bifurcation: the cluster formed by items 18–20 establishes a distinct pole, whereas cluster 30–34 constitutes a structural counterpoint. The intermediate points (21–29) delineate a transitional gradient between the two poles, suggesting a continuum of structural states. This bipolar configuration indicates the phase of maximum differentiation in welfare structures. Lower Panel (Terminal Configuration, points 35–51): Spatial geometry exhibits a tendency toward concentric reorganization, where point 49 emerges as a structural attractor. Elements 41, 42, and 44 form a core of second-order correlations, whereas the peripheral points (35–40, 43, 45–48, 50–51) establish a crown of controlled variability. This configuration suggests a phase of structural maturation characterized by the emergence of new stability patterns.

The observed three-phase evolution reveals a structural transformation process that transitions from an initial relatively homogeneous configuration through a phase of maximum differentiation to a state of structural reconfiguration characterized by new patterns of organization. This temporal sequence provides empirical evidence of the dynamic nature of welfare structures in the Andean region, suggesting the presence of self-regulation and structural reorganization mechanisms.

The interpretation of these inter-structural trajectories suggests that the determinants of well-being in the region have undergone significant transformations in their patterns of covariation, evidencing the complexity and dynamism of the underlying socioeconomic processes.

Figure 3 illustrates the three-phase evolution of well-being structures, showing the transition from an initial homogeneous configuration to a differentiated phase, and ultimately toward structural reorganization.

Figure 3.

Dual statistical analysis network diagram.

Figure 3.

Dual statistical analysis network diagram.

Based on the visualized results of the dual-STATIS analysis, the following robustness assessment was presented:

The robustness of the dual-STATIS analysis was evaluated using several statistical indicators to confirm the stability and reliability of the findings.

First, the percentage of inertia explained at each stage highlights the substantial representation of variability across the three time-panels. In the initial phase (items 1–17), 42.3% of the total inertia was concentrated on the first factor axes, capturing the predominant structural patterns. The intermediate phase (points 18–34) showed an increase in explained inertia to 47.8%, indicating greater structural differentiation. Finally, the last phase (points 35–51) consolidates 44.9% of inertia, signifying stabilization in the model’s explanatory power.

Second, the quality of the representation of variables in the compromise space is assessed using multiple indicators. The squared cosines of the center points exceeded 0.7, confirming a high-quality representation of the main variables. The dispersion within the three panels remained controlled with standard deviations below 0.5, reinforcing the stability of the representation. Additionally, the relative contributions of key structural elements were consistently above 10%, underscoring the significance of these variables in the overall analysis.

Third, the stability of temporal structures was verified by examining the relationships between consecutive time structures. The RV coefficient remained above 0.8, demonstrating a strong stability in the core relationships over time. Smooth transitions between the three panels were evident through the continuity of the trajectories of the plotted points. Furthermore, fundamental structural patterns persisted across the three periods, as indicated by an intraclass correlation exceeding 0.75.

Finally, the statistical significance of the observed correlations was confirmed using multiple tests. More than 85% of the main intra-structural correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.05), reinforcing the robustness of the identified patterns. The temporal stability of the correlations between key variables was evident, with a coefficient of variation below 0.2. Additionally, the determinants of the correlation matrices were significantly different from zero (p < 0.01), validating the non-singularity of the structures and ensuring the integrity of the analyses.

These robustness indicators suggest that the dual-STATIS analysis provides a reliable and stable representation of welfare covariation structures in the Andean region, with a significant explanatory capacity and adequate representation of the temporal and spatial relationships between variables.

The validation of the results obtained through dual-STATIS analysis was based on three complementary statistical procedures that strengthened the robustness of the identified findings.

Statistical Significance Analysis The identified correlation patterns were subjected to rigorous significance testing. Intra-structural correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.05) for 85% of the identified fundamental relationships. RV coefficients between consecutive temporal matrices presented significant values (p < 0.01, RV > 0.8), whereas matrix correlation tests using the Mantel test confirmed that structures differed significantly from random configurations (p < 0.001). In addition, the determinants of the correlation matrices were significantly different from zero (p < 0.01), thus validating the non-singularity of the identified structures.

Evaluation by Bootstrapping The implementation of 1000 bootstrap replications for each time panel provided substantial evidence of the stability of the identified structures. The 95% confidence intervals for the positions of the points in the compromise space exhibited reduced amplitudes (<0.3 standardized units). The clustering configuration demonstrated stability in more than 90% of the replications, whereas the main temporal trajectories maintained their configurations in 87% of the simulations. The principal eigenvalues exhibited coefficients of variation less than 20% across replications, suggesting significant stability in the dimensional structure of the analysis.

3.3. Cross-Validation

The implementation of the k-fold cross-validation (k = 5) corroborated the robustness of the identified patterns. The root mean square error of prediction (RMSE) remained below 0.15 for the principal configurations, while the coefficients of cross-determination (Q2) exceeded the threshold of 0.7 for the principal components. Sensitivity analysis, performed by random subsampling of 80% of the data, revealed a reproducibility above 92% for the principal configurations. Stability in cluster identification was confirmed by an adjusted Rand index above 0.85, and the eigenvalue hierarchy maintained a rank correlation above 0.9.

The convergence of these multiple validation indicators provides substantial evidence for the robustness and validity of the patterns identified through the dual-STATIS analysis. The consistency observed across the different validation methods suggests that the identified structures constitute genuine patterns in the welfare dynamics of the Andean region, transcending potential random fluctuations and methodological artifacts. These results strengthen the reliability of the conclusions derived from the main analysis, and provide a solid basis for the theoretical and practical implications of this study.

4. Discussion

The results obtained through the STATIS dual analysis reveal significant patterns in the evolution of the determinants of well-being in the Andean Community, showing both convergence and structural divergence that merit detailed discussion in the regional context.

These Andean findings sit squarely within broader debates on global SWB. The three-phase evolution we observe mirrors the worldwide shift documented by the first World Happiness Report and Gallup-Healthways surveys: an initial growth-led rise in life evaluations, a mid-decade divergence as institutional trust and social capital gained prominence, and a post-2017 re-alignment coinciding with the OECD push for standardized well-being metrics. The persistence of high Life-Ladder scores despite modest GDP confirms the Latin American happiness paradox highlighted by Graham and Lora [

9]. At the same time, the weaker income–happiness link in Colombia fits modernization and capability-approach arguments—wealth alone boosts well-being only when converted through effective, trustworthy institutions [

25,

26]. Ecuador’s Buen Vivir-driven emphasis on social support illustrates how regional philosophies can channel global trends toward locally rooted conceptions of a good life. Thus, our dual-STATIS results both replicate and refine global SWB patterns, showing how universal mechanisms—economic growth, governance quality, social capital—interact with distinctly Latin American cultural frameworks.

The identified temporal structure suggests a non-linear evolution in well-being patterns, coinciding with the findings of Rojas [

13] on the multidimensional complexity of well-being in Latin America. The initial configuration (2006–2010) shows relative structural homogeneity among countries, possibly reflecting the regional integration policies implemented in the previous decade, as pointed out by Núñez-Naranjo et al. [

16] in their analysis of Andean socioeconomic convergence.

The phase of structural differentiation observed in the intermediate period (2011–2016) coincides with that reported by Márquez et al. [

14] regarding the divergence in the development trajectories of Andean countries. This stage reveals a significant polarization in welfare structures, particularly evident in the separation between traditional socioeconomic indicators and social perception variables. This finding supports Burger et al.’s [

15] observations on the growing importance of institutional and cultural factors in determining regional welfare.

The partial convergence identified in the final period (2017–2022) presents parallels with the studies of Núñez-Naranjo et al. [

16] on the evolution of “Buen Vivir” in Ecuador, suggesting a possible harmonization between traditional and modern conceptions of well-being. However, the persistent structural differences between countries, particularly Colombia, coincide with Hanson’s [

10] observations on the differential role of state capacities in the promotion of well-being.

The temporal stability of the correlations between social support and subjective well-being corroborates Rowan’s [

2] finding of the universal importance of social networks in happiness. However, the observed variability in the influence of GDP per capita suggests greater complexity in the Andean context, supporting Diener and Seligman’s [

5] observations on the non-linear relationship between economic development and well-being.

The divergent trajectories in the perception of corruption and its relationship to well-being reflect Yee’s [

11] findings on the importance of institutional quality in developing societies. The persistence of these differences suggests the need to consider specific historical and cultural factors to understand regional well-being [

12].

A particularly relevant finding is the identification of country-specific covariation structures, suggesting the existence of “national welfare models” within the Andean region. This is consistent with the observations of Clark et al.’s [

32] observations on the importance of considering specific cultural contexts in the analysis of well-being.

The temporal evolution of well-being structures identified through dual-STATIS provides empirical evidence of the complexity of the development processes in the Andean region. The results suggest that, although there are trends towards convergence in certain aspects of well-being, national and cultural particularities continue to exert a significant influence in determining happiness and subjective well-being.

Specifically, Colombia’s covariation profile was distinct: its economic growth did not boost life satisfaction as strongly as in Ecuador or Peru. This suggests that factors like security and institutional trust are especially pivotal for Colombian well-being [

10,

15]. By contrast, Ecuador’s pattern underlined the influence of its unique cultural ethos of Buen Vivir—a development philosophy emphasizing communal and ecological well-being. Strong social support and community values in Ecuador appear to bolster happiness even amid economic fluctuations [

16,

31]. Peru, which aligned most closely with the common regional trend, exemplified a case where standard determinants of happiness (income, health, social support) operated as expected. Notably, Peru consistently reported very high social support, reflecting tight-knit family and community networks that are known to sustain well-being in Latin America [

13,

16]. These country-specific nuances underscore that while there is a shared regional framework, each nation follows its own path to happiness, shaped by its institutional context and cultural values.

These observations have significant implications for regional public policy, suggesting the need for a differentiated approach that recognizes both similarities and structural differences between countries. The evidence presented here supports the importance of considering specific cultural and social factors when designing interventions aimed at improving well-being in the Andean region.

The findings also point to the need for future research that deepens our understanding of the causal mechanisms underlying the identified covariation structures. The analysis of how country-specific institutional and cultural factors interact with traditional development variables to determine well-being is particularly relevant.

6. Conclusions

This study provides innovative empirical evidence on the multidimensional dynamics of well-being in the Andean Community through the application of the dual-STATIS method, allowing us to test the hypotheses initially proposed with significant results.

Regarding the first hypothesis (H1), which postulated that the relationship between economic factors and happiness is mediated by institutional quality, the results confirm this mediation, revealing that the covariation structure between GDP per capita and the Life Ladder is significantly modulated by institutional variables, particularly the perception of corruption and the freedom to make decisions. This institutional mediation partially explains the differences in welfare among countries with similar levels of economic development.

Regarding the second hypothesis (H2), which proposes that social support has a greater impact in areas of lower economic development, the results provide partial evidence. Although there is a significant correlation between social support and well-being at all levels of development, its intensity varies in a non-linear manner with economic level, suggesting a more complex relationship than initially proposed.

The third hypothesis (H3), which posits convergence in the determinants of happiness between countries, partially supports the data. The dual-STATIS analysis revealed a three-phase evolution culminating in partial convergence, while maintaining significant national specificities in the covariate structures.

These key findings reveal a non-linear evolution in welfare structures, from initial homogeneity through a phase of marked differentiation to partial convergence with national distinctiveness. This evolutionary trajectory suggests that well-being in the Andean region emerges from dynamic interactions among socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural factors specific to each national context.

The identification of distinctive covariation structures for each country questions the universal applicability of traditional models of well-being and suggests the existence of “national archetypes of happiness” that respond to unique configurations of social, economic, and cultural factors. This observation has profound implications for the design of public policies, suggesting the need for a differentiated approach that recognizes and capitalizes on national specificities.

The methodological robustness of the analysis, validated by multiple statistical procedures, provides a solid basis for future research and suggests the need to reconsider traditional methodological approaches in the study of regional welfare. The temporal correlations identified between variables traditionally considered independent revealed synergies and antagonisms that were previously undocumented in the literature on welfare in the Andean region.

Finally, this study establishes a new paradigm in welfare research in Latin America, demonstrating the importance of considering temporal evolution and cultural specificity in the analysis of human development. The evidence presented inaugurates a new era in understanding regional well-being and establishes solid empirical foundations for the development of more effective and culturally appropriate public policies.