Employee Motivation and Job Performance of Non-Academic Staff in Chinese Universities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Literature Review

2.1. Research Framework

2.2. Description of Variables

2.3. Research Hypotheses

2.3.1. Hypothesis 1: Monetary Motivations and Financial Performance

2.3.2. Hypothesis 2: Non-Monetary Motivations and Financial Performance

2.3.3. Hypothesis 3: Monetary Motivations and Non-Financial Performance

2.3.4. Hypothesis 4: Non-Monetary Motivations and Non-Financial Performance

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Measurement Model Assessment

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

| Demographic Variables | Frequency (N = 356) | Percent % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 183 | 51.4 |

| Female | 173 | 48.6 |

| Age group | ||

| 26–30 | 134 | 37.6 |

| 31–35 | 97 | 27.2 |

| 36–40 | 64 | 18.0 |

| 41–45 | 33 | 9.3 |

| 46–50 | 17 | 4.8 |

| >51 | 11 | 3.1 |

| Education | ||

| Bachelor’s | 145 | 40.7 |

| Master’s | 175 | 49.2 |

| PhD | 36 | 10.1 |

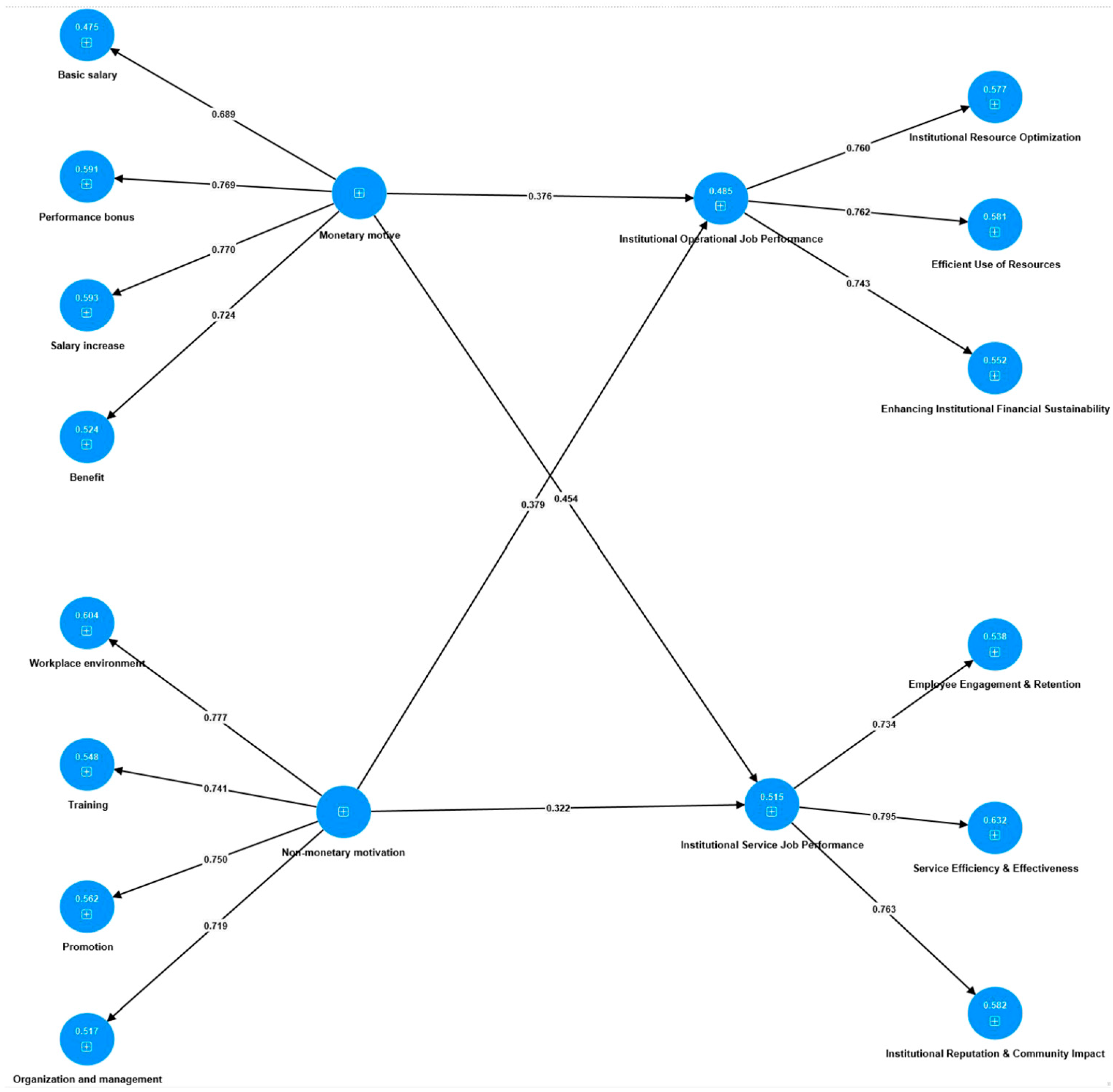

4.2. Structural Model

4.3. Discussion of the Results

4.3.1. Hypothesis 1

4.3.2. Hypothesis 2

4.3.3. Hypothesis 3

4.3.4. Hypothesis 4

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SEM-PLS | Structural Equation Modeling using Partial Least |

| Squares AVE | Average variance extracted |

| H2 | Hypothesis 2 |

| H3 | Hypothesis 3 |

| H4 | Hypothesis 4 |

References

- Zeng, Z.L. Optimal Design of Salary Management System of H Company. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C.L. Looking for real “motivators”. Hum. Resour. Dev. 2008, 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.Z. Research on Performance Management of Grass-Roots Employees in China Industrial and Commercial Bank. Master’s Thesis, Hainan University, Haikou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.D. Research on Performance Management of Multinational Corporations in China. Ph.D. Thesis, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, L.Q.; Guo, Y.C. Review of University Administrative Motivation Research: A review of problems and future prospects. Chin. J. Pers. Sci. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G. Investigation and research on job burnout of grassroots administrative staff in colleges and universities. J. Yichun Univ. 2012, 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Gao, P.J. Analysis of the performance evaluation model of university administrative personnel based on the analytic hierarchy process. J. Jiujiang Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. A study on the causes and strategies of job burnout of grass-roots administrative personnel in universities. Educ. Mod. 2017, 280–282. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.Q.; Guan, X.L. Research on Incentive Mechanism of grass-roots administrative Staff in universities based on Hierarchy of Needs Theory under the background of “Double first-class”—A case study of S University. Heilongjiang Educ. (Theory Pract.) 2019, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, F.; Mausner, B.; Snyderman, B.B. The Motivation to Work, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.J. Herzberg motivation-Development of health factor theory. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 25, 633–634. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.Y. Review and application of management incentive theory. Sci. Manag. 2006, 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D.C. The Achieving Society; Van Nostrand: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, H.; Wang, Y. Research on the resolution strategy of job burnout of administrative personnel in secondary colleges. Beijing Educ. (High. Educ.) 2023, 87–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.M. Review of western enterprise incentive theory. Econ. Rev. 2006, 4, 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, V.H. Work and Motivation; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. Discussion on the application of incentive theory in modern enterprise management. Financ. Econ. Circ. 2021, 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. Analysis on salary incentive mechanism of university administrators. J. Zhejiang Shuren Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2019, 100–103. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, C.J.; Zhao, F.J. A survey on job burnout of university administrators in prefectural and prefectural universities from the perspective of polycentric governance. Guiyang Coll. J. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, W. Research on the Incentive of Knowledge Workers in the Structure of Total Compensation. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Technology and Business University, Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Feng, S. The Relationship between Competence and Job performance of university administrators. Econ. Trade Pract. 2018, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.M.; Ji, D.H.; Xu, F.W. Review and prospect of incentive research. J. Econ. Res. 2009, 116–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.Y.; Fu, Y. Application of incentive theory in enterprise management. Enterp. Econ. 2011, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Wider, W.; Zhang, X.; Fauzi, M.A.; Wong, C.H.; Jiang, L.; Udang, L.N. Triggering Chinese lecturers’ intrinsic work motivation by value-based leadership and growth mindset: Generation difference by using multigroup analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, R. EFL teachers’ motivation of professional development at the university level in China. Forum Linguist. Stud. 2024, 6, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.F. International comparative analysis of salary systems for scientific researchers in public scientific research institutions. Glob. Sci. Technol. Econ. Outlook 2016, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y. An analysis on the motivation of university administrators: Dilemma and outlet. Mod. Econ. Inf. 2016, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, H. Construction and Application of Employee Performance Incentive Model. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.L.; Xu, D.J. Questionnaire design method based on reliability analysis. Mod. Educ. 2015, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.F. Research on Incentive Mechanism of Grass-roots Administrative Staff in Universities with “Double First-class” Construction. Master’s Thesis, Henan University, Kaifeng, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.L. Research on the impact of comprehensive compensation on the technological innovation capabilities of high-tech enterprises. Sci. Technol. Sq. 2009, 133–135. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, P. Compensation System for Knowledge-based Workers in High-tech Enterprises. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.P.; Jin, J. On the long-term incentive mechanism for enterprise technology employees. Sci. Technol. Entrep. Mon. 2008, 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, J. Comprehensive compensation function and its non-monetary performance. J. Chongqing Electr. Power Coll. 2023, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, Q.W.; Wang, S.H.; Wu, M.X. Total Compensation Strategy: Incentive Mechanism for knowledge-based workers. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2004, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.F. Research on Countermeasures of Employee Performance Management in Company A in the New Era. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Technology, Tianjin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.C.; Wang, L.J. Management innovation for the 21st century. J. Guiyang Jinzhu Univ. 2001, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, B. Discussion on new employee incentive measures of the post-80s generation. Technol. Mark. 2007, 3, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, S.L. Research on incentive mechanism of university administrators in the new era. Think Tank Times 2020, 292–293. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H.H. Research on Teacher Motivation Issues at TY Private School Based on the Two-Factor Theory; Henan University of Economics and Law: Henan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.N. Research on the construction of performance appraisal system for university administrators. Intelligence 2019, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Analysis of salary incentives for university administrators. Off. Bus. 2023, 158–160. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.J. Master’s Degree in Research on Countermeasures to Improve the Incentive Mechanism of Administrative Personnel in Universities in my Country. Ph.D. Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Research on Factors Influencing Turnover Intention of New Generation of Intellectual Workers. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.J. Research on the relationship between competence and job performance of university administrators. Intelligence 2017, 122–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.S. Research on the application of incentive mechanism in university human resource management. Chin. Manag. Informatiz. 2022, 167–169. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Zhang, X.Y. Research on Long-term incentive Mechanism for University Administrators in the New Era. J. Hubei Open Vocat. Coll. 2021, 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Z. Constructing incentive mechanism for university administrators. Hum. Resour. 2023, 6, 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Construction of university teacher performance management system. High. Educ. Res. 2007, 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Bo, M.Y. Research on University Income Management from the perspective of Internal control. Educ. Financ. Account. Res. 2022, 93, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Feng, Z. Discussion on the transformation of college cashier models under the background of intelligent finance. China Gen. Account. 2022, 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, L. Research on the income increase and income assessment path of colleges and universities. Account. 2022, 116–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Satisfying employees’ psychological Needs based on motivation theory. Hum. Resour. 2023, 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, T.T. On the inducement and organizational intervention strategy of job burnout of young administrative staff in universities and colleges. In Chinese Science and Education Innovation Guide; China Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2013; pp. 219–220. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Cui, M.; Pang, J.; Yan, W. Analysis of the upgrading reform of the university staff system and its driving mechanism. China High. Educ. Res. 2023, 39, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.H. Discussion on income distribution in colleges and universities. Financ. Financ. 2016, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, Y. Discussion on the system architecture, implementation paths and application trends of intelligent finance. Manag. Account. Res. 2018, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B.F. Science and Human Behavior; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.Y.; Xue, H. Analysis of existing problems and countermeasures in administrative management of universities. J. Jilin Radio Telev. Univ. 2021, 6, 123–125. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Research on the Incentive Problem of Township Civil Servants from the Perspective of Potter-Lawler Comprehensive Incentive Model. Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.H. Research on University administrative staff motivation based on grey correlation analysis. Univ. Logist. Res. 2016, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.J. Research on Motivational Factors and Their Effects on University Teachers’ Performance Based on Group Characteristics. Ph.D. Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Wang, Y. A preliminary study on promoting the professional construction of teaching management teams in colleges and universities. J. Fuyang Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2006, 106–107. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y. Some thoughts on income generation of colleges and universities. Accountants 2020, 72–73. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.H.; Liu, B. Public policy formulation in China from the perspective of holiday system. Jiangsu Quotient 2015, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Kong, X.D. Analysis on income management in colleges and universities. Accountant 2016, 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.R. Analysis on incentive measures for university administrators. Teach. Educ. People 2012, 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.C. Research on Teaching Incentive Mechanism of University Teachers Based on Potter-Lawler Comprehensive Incentive Model. Master’s Thesis, Hainan University, Haikou, Hainan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S. Research on Motivational Strategies of Knowledge Workers in Innovative SMEs Based on Psychological Contract. Doctoral Dissertation, Central South University, Changsha, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, Q.; Yu, H.J.; Jiang, Y.S.; Miao, M. Research on the group difference of motivation structure model of university teachers. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.Y. Analysis on employee performance management optimization in functional departments of enterprises. J. Technol. Entrep. 2020, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.C.; Ling, J.Y. The incentive Path of non-monetary compensation based on Rooted theory. China’s Circ. Econ. 2023, 90–102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.L.; Wen, X.X.; Zhang, X.M. Empirical analysis of motivation factors for knowledge workers. Mall Mod. 2006, 3, 241–242. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, B. Research on Employee Incentive Mechanism of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.L. An analysis of employee motivation strategies based on two-factor motivation theory. Qual. Mark. 2022, 103–105. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.Y. Research on Incentives for College Teachers. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yao; Chen, Y.; Yang. Game analysis of incentive factors in compensation theory under the two-factor theory. Mod. Trade Ind. 2008, 164–165. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, F. Master’s Degree in Research on Using Big Data to Promote the Work Advantages of College Counsellors. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.H. Research on Enterprise Employee Performance Management from a Humanized Perspective. Master’s Thesis, Ningbo University, Ningbo, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, J.Y.; Zhang, R. Research on Incentive Mechanism of University Administrators—A Case study of Changzhi University. Foreign Trade Econ. 2020, 136–138. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.Z. Research on Employee Motivation of H Company. Master’s Thesis, Sichuan Normal University, Chengdu, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W. The impact of monetary incentives on employee work performance: Evidence from administrative staff in Chinese universities. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. 2019, 25, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H. Effective use of motivation policies in human resource development. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.Y. Application of incentive Theory to Higher education management. Adult Educ. China 2019, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, H.F. Research on work engagement of university managers. China High. Educ. 2018, 5, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.L.; Huang, Z.B.; Yang, L.H.; Cui, K. Investigation on main motivating factors of young people in different positions in state-owned enterprises and suggestions on countermeasures. Enterp. Reform Manag. 2019, 57–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.W.; Xia, J.P. Modernization of university governance system and governance capacity: Connotation and approach. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 35, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, J.; Rosen, C.C.; Gabriel, A.S.; Puranik, H.; Johnson, R.E.; Ferris, D.L. Why and for whom does the pressure to help hurt others? Affective and cognitive mechanisms linking helping pressure to workplace deviance. Pers. Psychol. 2020, 73, 333–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.A. The Yang Triangle of Organizational Capability: The Secret to Sustainable Corporate Success, 2nd ed.; Mechanical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, G.S.; Xu, H.H. Analysis of civil servant job burnout from the perspective of the Two-Factor Theory. Chin. Public Adm. 2015, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, R.Y.; Shan, H.; Fu, F.T. Optimization strategies for position allowances under the reform of compensation systems. Mod. Bus. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, W. Research on incentive mechanism of university administrators based on hierarchy of needs theory. Contemp. Educ. Theory Pract. 2014, 154–156. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, K. Bonus schemes must be well drafted, transparent and fair. Prop. Week 2019, 86, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Kuai, P.Z.; Zhang, Z.H.; Li, Z.H. The impact of incentive strategies on the performance of knowledge workers: Based on Social exchange Theory. J. Beijing Vocat. Coll. Labor Secur. 2019, 31, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.J. Motivation Strategies for New Generation Employees of A Property Company in Shanxi Province. Master’s Thesis, Shanxi University of Finance and Economics, Shanxi, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.G.; Guo, Z.B.; Sun, Y. Research on the incentive mechanism of professional development of the staff of the general office of university organs: A case study of Tsinghua University. Educ. Teach. Forum 2020, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.R. Research on corporate employee motivation mechanisms based on the Two-Factor Theory: A case study of “post-1990s” employees. Enterp. Sci. Technol. Dev. 2020, 153–155. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.P. Issues and countermeasures in corporate compensation and performance management. Invest. Entrep. 2024, 35, 121–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G.R. Research on motivation mechanisms for grassroots civil servants in remote and difficult areas based on the Two-Factor Theory. J. Xiamen Spec. Econ. Zone Party Sch. 2018, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.F. Optimization research on modern corporate human resource compensation management. Vitality 2024, 42, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, H. Practice and application of the two-factor theory in human resource management of educational enterprises. Manag. Sch. 2022, 79–81. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. Practical problems and countermeasures of the comprehensive implementation of performance management in universities. Public Invest. Guide 2021, 12, 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.X. Innovative practices in compensation management in human resource management. Vitality 2024, 42, 169–171. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.M.; Tang, Y.; Wang, S.F.; Wu, G.S.; Wang, X.Y. Research on human resource management strategies in the new situation. Mod. Mark. 2024, 107–109. [Google Scholar]

| Part | Variable | Project Total |

|---|---|---|

| Part A | Monetary motivations | 20 |

| Non-monetary motivations | 20 | |

| Part B | Financial performance | 15 |

| Non-financial performance | 15 |

| Monetary Motivations | Non-Monetary Motivations | Financial Performance | Non-Financial Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIF | 1.41 | 1.756 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Dimension | Cronbach’s Alpha | No. of Items |

|---|---|---|

| Basic salary | 0.875 | 5 |

| Benefits | 0.885 | 5 |

| Bonus | 0.879 | 5 |

| Fund management | 0.886 | 5 |

| Generate income | 0.875 | 5 |

| Increase income | 0.878 | 5 |

| Job service quality | 0.88 | 5 |

| Organization management | 0.87 | 5 |

| Social influence | 0.894 | 5 |

| Workplace environment | 0.88 | 5 |

| Performance management | 0.88 | 5 |

| Promotion | 0.884 | 5 |

| Satisfaction | 0.877 | 5 |

| Training | 0.875 | 5 |

| Constructs Outer | Items | Loadings | AVE | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BS1 | 0.812 | |||

| BS2 | 0.823 | |||

| Basic salary | BS3 | 0.809 | 0.668 | 0.909 |

| BS4 | 0.823 | |||

| BS5 | 0.818 | |||

| BE1 | 0.838 | |||

| BE2 | 0.856 | |||

| Benefits | BE3 | 0.863 | 0.685 | 0.916 |

| BE4 | 0.789 | |||

| BE5 | 0.791 | |||

| BO1 | 0.790 | |||

| BO2 | 0.786 | |||

| Bonus | BO3 | 0.851 | 0.674 | 0.912 |

| BO4 | 0.832 | |||

| BO5 | 0.842 | |||

| FM1 | 0.827 | |||

| FM2 | 0.831 | |||

| Fund management | FM3 | 0.828 | 0.687 | 0.917 |

| FM4 | 0.815 | |||

| FM5 | 0.843 | |||

| GI1 | 0.826 | |||

| GI2 | 0.813 | |||

| Generate income | GI3 | 0.802 | 0.665 | 0.909 |

| GI4 | 0.814 | |||

| GI5 | 0.825 | |||

| LI1 | 0.839 | |||

| LI2 | 0.824 | |||

| Increase income | LI3 | 0.785 | 0.673 | 0.911 |

| LI4 | 0.813 | |||

| LI5 | 0.839 | |||

| JS1 | 0.833 | |||

| JS2 | 0.817 | |||

| Job service quality | JS3 | 0.821 | 0.677 | 0.913 |

| JS4 | 0.798 | |||

| JS5 | 0.843 | |||

| OM1 | 0.838 | |||

| OM2 | 0.807 | |||

| Organization management | OM3 | 0.803 | 0.657 | 0.906 |

| OM4 | 0.799 | |||

| OM5 | 0.806 | |||

| SI1 | 0.848 | |||

| SI2 | 0.822 | |||

| Social influence | SI3 | 0.845 | 0.703 | 0.922 |

| SI4 | 0.824 | |||

| SI5 | 0.851 | |||

| WE1 | 0.837 | |||

| WE2 | 0.823 | |||

| Workplace environment | WE3 | 0.807 | 0.675 | 0.912 |

| WE4 | 0.822 | |||

| WE5 | 0.819 | |||

| Performance management | PM1 | 0.833 | 0.676 | 0.912 |

| PM2 | 0.789 | |||

| PM3 | 0.812 | |||

| PM4 | 0.841 | |||

| PM5 | 0.834 | |||

| PR1 | 0.828 | |||

| PR2 | 0.827 | |||

| Promotion | PR3 | 0.838 | 0.683 | 0.915 |

| PR4 | 0.803 | |||

| PR5 | 0.836 | |||

| SA1 | 0.830 | |||

| SA2 | 0.817 | |||

| Satisfaction | SA3 | 0.818 | 0.67 | 0.91 |

| SA4 | 0.831 | |||

| SA5 | 0.796 | |||

| TR1 | 0.837 | |||

| TR2 | 0.828 | |||

| Training | TR3 | 0.795 | 0.668 | 0.909 |

| TR4 | 0.835 | |||

| TR5 | 0.789 | |||

| Monetary Motivations | Non-Monetary Motivations | Financial Performance | Non-Financial Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monetary Motivations Non-monetary Motivations | 1 0.699 ** | 1 | ||

| Financial Performance Non-financial Performance | 0.638 ** 0.677 ** | 0.641 ** 0.639 ** | 1 0.608 ** | 1 |

| Financial Performance | Monetary Motivations | Non-Monetary Motivations | Non-Financial Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Performance | 0.620 | |||

| Monetary Motivations | 0.641 | 0.607 | ||

| Non-monetary Motivations | 0.642 | 0.699 | 0.612 | |

| Non-financial Performance | 0.608 | 0.680 | 0.64 | 0.632 |

| Monetary Motivations | Non-Monetary Motivations | Financial Performance | Non-Financial Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monetary Motivations | ||||

| Non-monetary Motivations | 0.768 | |||

| Financial Performance | 0.711 | 0.714 | ||

| Non-financial Performance | 0.683 | 0.751 | 0.708 |

| Relationship | β | p Values | T-Value | Decision | f2 | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic salary -> Fund | −0.008 | 0.883 | 0.147 | Rejected | 0 | |

| Basic salary -> Generate | 0.076 | 0.171 | 1.369 | Rejected | 0.006 | Small |

| income | ||||||

| Basic salary -> Increase income | 0.025 | 0.652 | 0.451 | Rejected | 0.001 | |

| Basic salary -> Job service | 0.118 | 0.023 | 2.267 | Accepted | 0.016 | Medium |

| quality | ||||||

| Basic salary -> Social influence | 0.034 | 0.54 | 0.613 | Rejected | 0.001 | Small |

| Basic salary -> Satisfaction | 0.05 | 0.369 | 0.898 | Rejected | 0.002 | Small |

| Benefits -> Fund management | 0.06 | 0.275 | 1.091 | Rejected | 0.003 | Small |

| Benefits -> Generate income | 0.016 | 0.775 | 0.286 | Rejected | 0 | |

| Benefits -> Increase income | 0.12 | 0.035 | 2.109 | Accepted | 0.013 | Medium |

| Benefits -> Job service quality | 0.128 | 0.016 | 2.402 | Accepted | 0.018 | Medium |

| management | ||||||

| Benefits -> Social influence | 0.112 | 0.049 | 1.972 | Accepted | 0.012 | Medium |

| Benefits -> Satisfaction | 0.172 | 0.002 | 3.034 | Accepted | 0.027 | Large |

| Bonus -> Fund management | 0.143 | 0.012 | 2.505 | Accepted | 0.019 | Medium |

| Bonus -> Generate income | 0.12 | 0.029 | 2.188 | Accepted | 0.013 | Medium |

| Bonus -> Increase income | 0.084 | 0.128 | 1.523 | Rejected | 0.006 | Small |

| Bonus -> Job service quality | 0.16 | 0.005 | 2.795 | Accepted | 0.027 | Large |

| Bonus -> Social influence | 0.105 | 0.062 | 1.866 | Rejected | 0.01 | Medium |

| Bonus -> Satisfaction | 0.125 | 0.034 | 2.121 | Accepted | 0.014 | Medium |

| Organization management ->Fund management | 0.046 | 0.424 | 0.8 | Rejected | 0.002 | Small |

| Organization management -> Generate income | 0.136 | 0.013 | 2.498 | Accepted | 0.018 | Medium |

| Organization management -> Increase income | 0.132 | 0.016 | 2.402 | Accepted | 0.016 | Medium |

| Organization management -> Job service quality | 0.019 | 0.715 | 0.366 | Rejected | 0 | |

| Organization management -> Social influence | 0.155 | 0.006 | 2.748 | Accepted | 0.023 | Large |

| Organization management -> Satisfaction | 0.062 | 0.285 | 1.068 | Rejected | 0.004 | Small |

| Workplace environment -> Fund management | 0.095 | 0.095 | 1.669 | Rejected | 0.008 | Small |

| Workplace environment -> Generate income | 0.151 | 0.01 | 2.582 | Accepted | 0.02 | Small |

| Workplace environment -> Increase income | 0.086 | 0.148 | 1.449 | Rejected | 0.006 | Small |

| Workplace environment -> Job service quality | 0.03 | 0.579 | 0.554 | Rejected | 0.001 | Small |

| Workplace environment -> Social influence | −0.04 | 0.495 | 0.683 | Rejected | 0.001 | Small |

| Workplace environment -> Satisfaction | 0.054 | 0.382 | 0.874 | Rejected | 0.002 | Small |

| Performance management -> Fund management | 0.175 | 0.002 | 3.051 | Accepted | 0.028 | Large |

| Performance management -> Generate income | 0.15 | 0.01 | 2.581 | Accepted | 0.021 | Large |

| Performance management -> Increase income | 0.157 | 0.007 | 2.688 | Accepted | 0.022 | Large |

| Performance management -> Job service quality | 0.165 | 0.002 | 3.034 | Accepted | 0.029 | Large |

| Performance management -> Social influence | 0.134 | 0.016 | 2.41 | Accepted | 0.016 | Medium |

| Performance management -> Satisfaction | 0.111 | 0.062 | 1.864 | Rejected | 0.011 | Medium |

| Promotion -> Fund management | 0.138 | 0.012 | 2.527 | Accepted | 0.018 | Medium |

| Promotion -> Generate income | 0.053 | 0.316 | 1.003 | Rejected | 0.003 | Small |

| Promotion -> Increase income | 0.04 | 0.466 | 0.729 | Rejected | 0.001 | Small |

| Promotion -> Job service quality | 0.104 | 0.054 | 1.93 | Rejected | 0.012 | Medium |

| Promotion -> Social influence | 0.152 | 0.008 | 2.664 | Accepted | 0.021 | Large |

| Promotion -> Satisfaction | 0.131 | 0.015 | 2.424 | Accepted | 0.015 | Medium |

| Training -> Fund management | 0.122 | 0.034 | 2.126 | Accepted | 0.015 | Medium |

| Training -> Generate income | 0.072 | 0.199 | 1.285 | Rejected | 0.005 | Small |

| Training -> Increase income | 0.099 | 0.082 | 1.739 | Rejected | 0.009 | Small |

| Training -> Job service quality | 0.18 | 0 | 3.511 | Accepted | 0.037 | Large |

| Training -> Social influence | 0.115 | 0.038 | 2.081 | Accepted | 0.013 | Medium |

| Training -> Satisfaction | 0.029 | 0.596 | 0.53 | Rejected | 0.001 | Small |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ce, Z.; Ab-Rahim, R.; Siali, F.; Mokhtar, N. Employee Motivation and Job Performance of Non-Academic Staff in Chinese Universities. Societies 2025, 15, 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080227

Ce Z, Ab-Rahim R, Siali F, Mokhtar N. Employee Motivation and Job Performance of Non-Academic Staff in Chinese Universities. Societies. 2025; 15(8):227. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080227

Chicago/Turabian StyleCe, Zhang, Rossazana Ab-Rahim, Fadilah Siali, and Nuradibah Mokhtar. 2025. "Employee Motivation and Job Performance of Non-Academic Staff in Chinese Universities" Societies 15, no. 8: 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080227

APA StyleCe, Z., Ab-Rahim, R., Siali, F., & Mokhtar, N. (2025). Employee Motivation and Job Performance of Non-Academic Staff in Chinese Universities. Societies, 15(8), 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080227