To Stay or to Migrate: Driving Factors and Formation Mechanisms of Rural Households’ Decisions Regarding Rural–Urban Student Migration in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

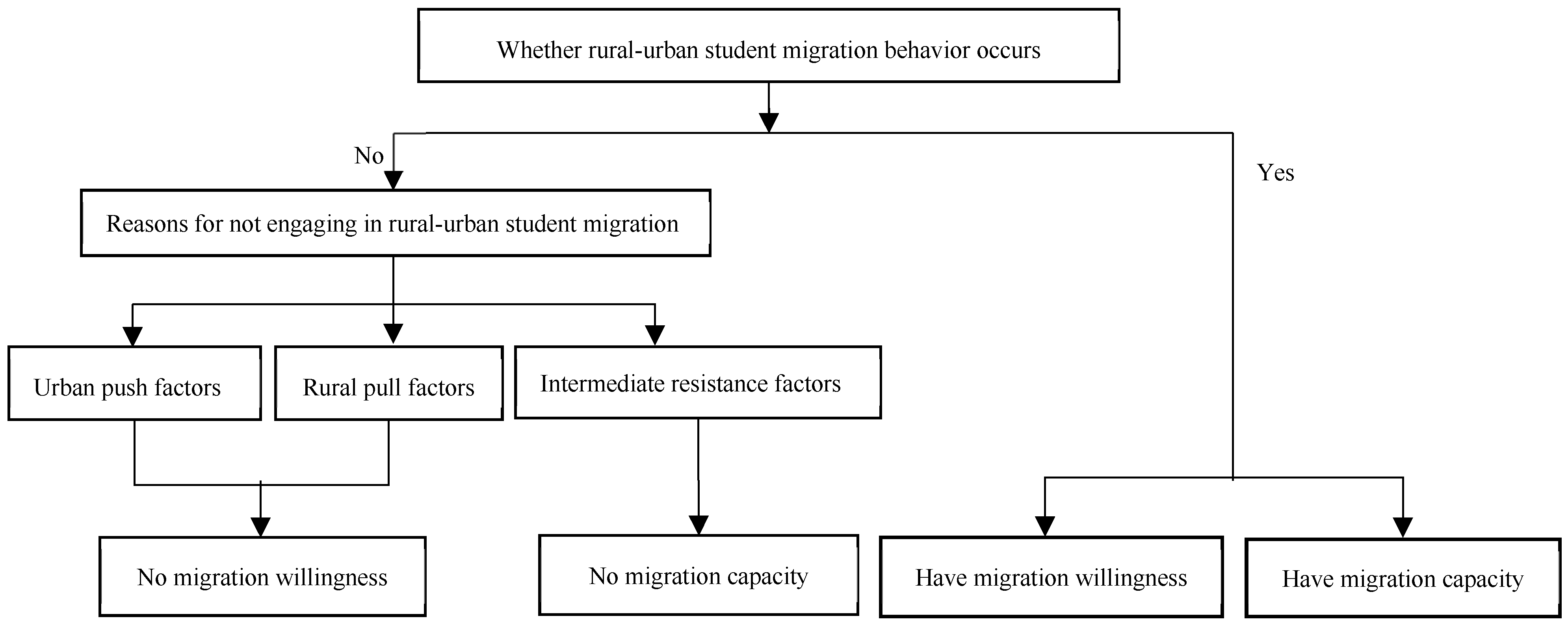

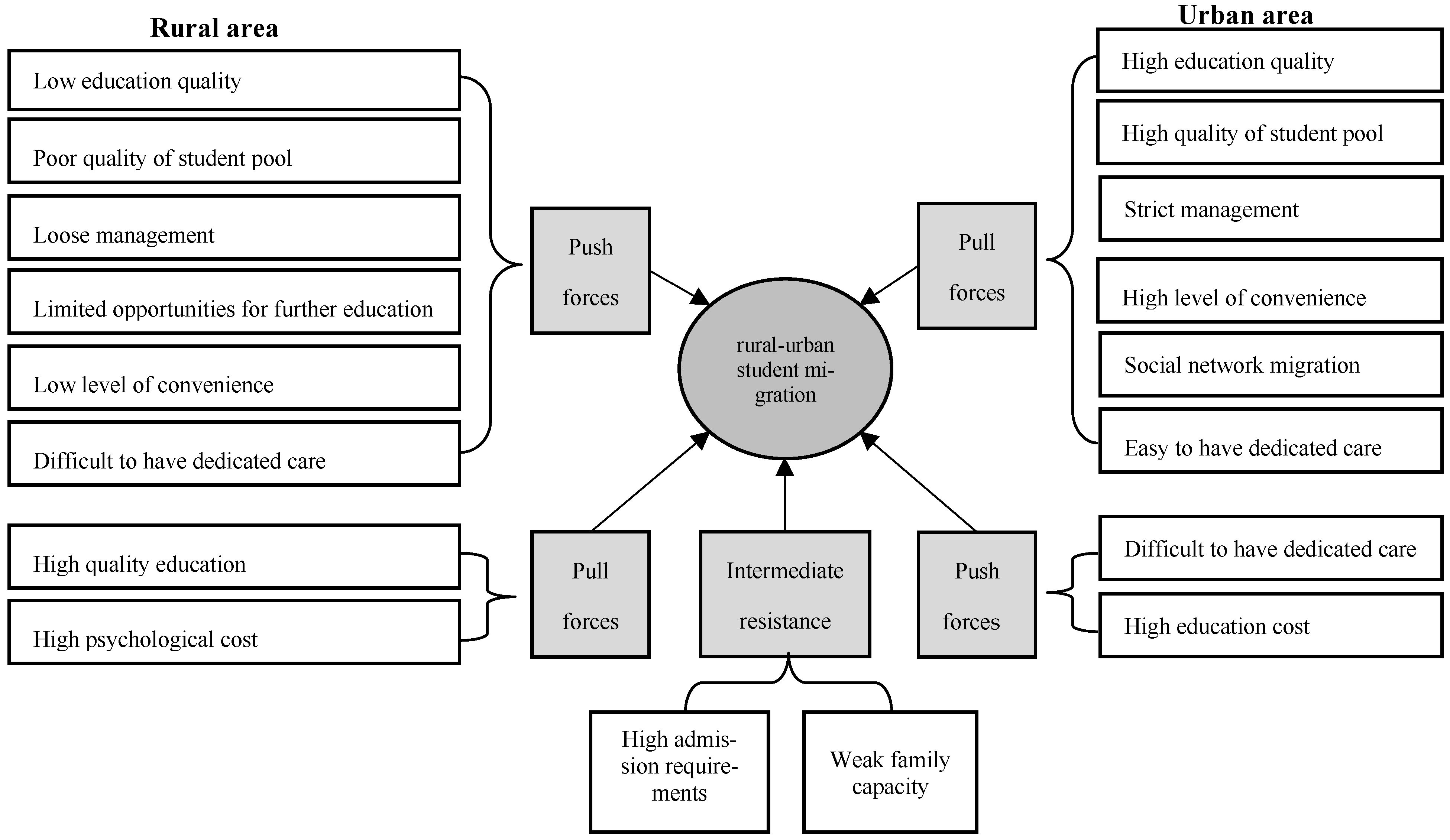

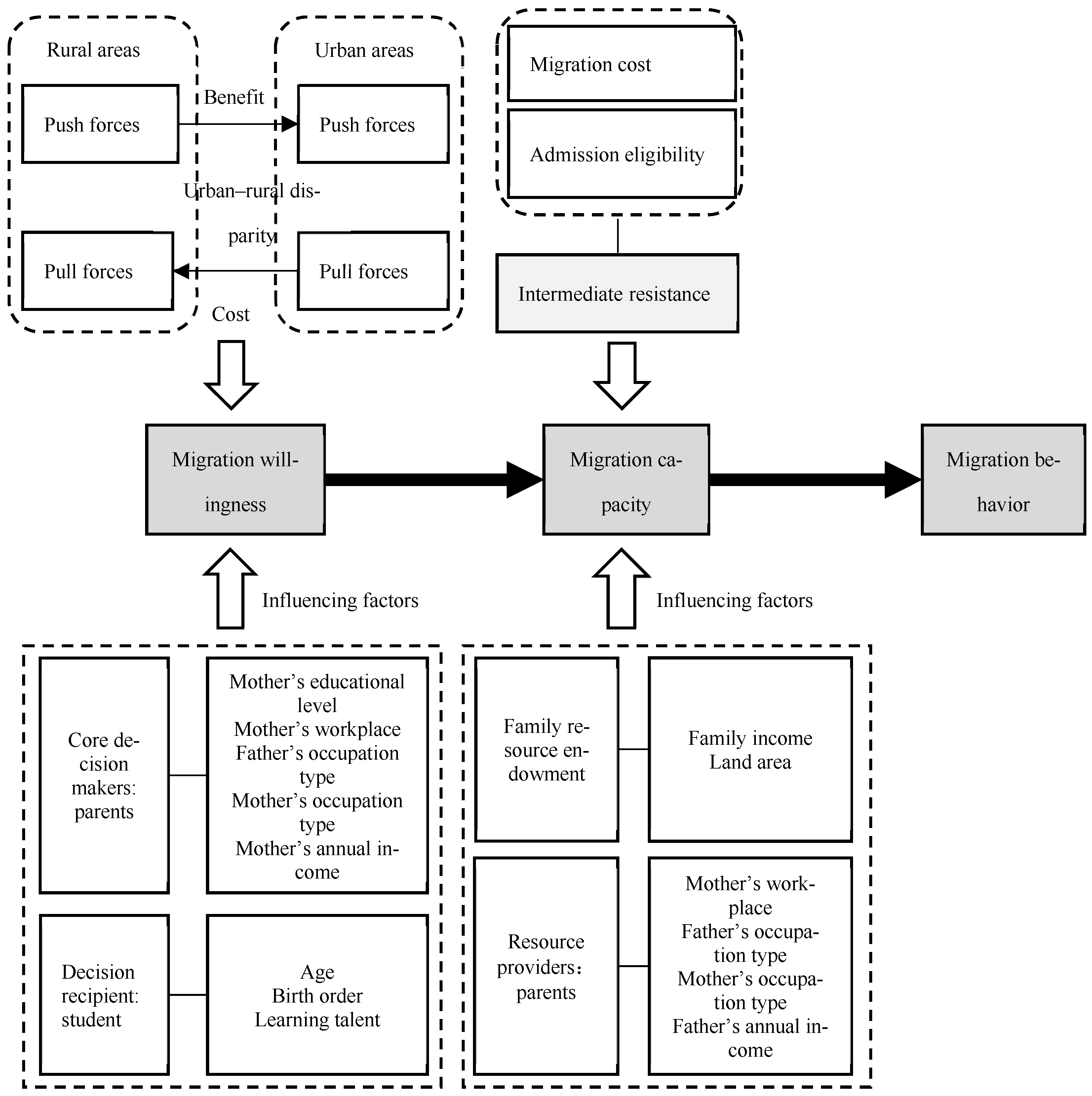

2. Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Basic Model

- There are two administrative regions in the economic system: rural areas and urban areas. Rural areas engage in agricultural production activities, while urban areas engage in industrial and service production activities (collectively referred to as non-agricultural production activities).

- Residence is specified to the county-level administrative region, and the household registration types are divided into urban hukou and rural hukou. The initial place of residence for the representative rural household i is located in rural areas, and household members have rural hukou status.

- Each adult laborer is assumed to have 1 unit time endowment, and, post-childbirth, time is allocated between market labor and child care.

- Family is the basic decision-making unit, and key decisions within the family are made by the adult laborers (parents).

- The utility function is additive and separable, with a first derivative greater than 0 and a second derivative less than 0.

- The quality of public education resources varies significantly by location, with urban areas generally offering higher-quality resources than rural areas.

2.1.1. Two-Sector Production Functions

- 1.

- Urban sector. The urban sector includes both high-skilled and low-skilled labor. Its production function follows a CES form:

- 2.

- Rural sector. The production function of the rural sector is

2.1.2. Education Production Function

2.1.3. Family Utility Function

2.2. Key Decisions of Rural Households

2.2.1. Migration Willingness

- (1)

- When the cost of rural–urban student migration is lower ;

- (2)

- When rural–urban student migration enables a transition from parent–child separation to co-residence (ρ changes from 0 to 1);

- (3)

- When the expected wage rate of high-skilled labor in urban areas is higher ;

- (4)

- When the probability of becoming high-skilled labor is lower if rural–urban student migration does not occur ;

- (5)

- When the parent’s altruistic tendency towards the offspring is stronger .

- (1)

- The impact of family resource endowment on migration willingness: From formula (16), it can be seen that when rural households make rural–urban student migration decisions, the predetermined family income does not affect , and therefore does not influence the migration willingness. This implies that family resource endowments, as represented by family income, do not impact migration willingness.

- (2)

- The impact of parental individual endowment on migration willingness: Parental individual endowment can influence , consequently affecting migration willingness. Firstly, the parent’s workplace affects the cost of rural–urban student migration and the parameter for parent–child separation. When the parent’s workplace is in the city, the offspring are more likely to meet the enrollment conditions for urban migrant workers, which reduces the cost of rural–urban student migration. Additionally, when the parent’s workplace is in the city, the offspring are more likely to live together with the parents after migration, reducing the negative utility generated by parent–child separation. Secondly, parental occupational background and personal income shape the amount of exposure they have to urban labor market information, which then influences how accurately they expect high-skilled wages . Studies have shown that rural farmers—with very limited access to urban wage information—tend to underestimate city wage levels. In contrast, white-collar parents—through their work experience or social network—possess more accurate expectations, whereas blue-collar workers fall somewhere in between [21]. In the context of rural China, empirical findings confirm that parents’ occupations and incomes influence their educational return expectations [22]. Thus, parents with white-collar occupations or higher personal income have a stronger migration willingness. Finally, the parents’ levels of education indirectly influence migration willingness by affecting their workplace, occupation type, and personal annual income. The higher the parents’ levels of education, the stronger the migration willingness.

- (3)

- The impact of the student’s individual characteristics on migration willingness: The student’s individual characteristics can influence and , consequently affecting migration willingness. Firstly, the student’s learning talent impacts the probability of becoming a high-skilled labor when rural–urban student migration does not occur. In rural areas with relatively low education quality, individuals with higher learning talent are more capable of acquiring knowledge and skills, even under limited conditions, and thus have a greater probability of becoming a high-skilled laborer. In contrast, individuals with lower learning talent typically require more intensive educational support—both public and familial—to reach a comparable skill level [23]. Consequently, for less talented students, remaining in rural areas where educational resources are scarce reduces their chances of becoming a high-skilled laborer. As a result, rural households with less talented children are more inclined to pursue urban education through migration, viewing it as a necessary strategy to compensate for limited local educational opportunities. Thus, the lower the student’s learning talent, the higher the migration willingness of rural households. Secondly, the student’s gender, age, birth order, and other personal characteristics can affect —namely, the parent’s altruistic tendency. For instance, in multi-child households, altruism is not necessarily equal across offspring. Parents may exhibit greater altruism toward children who are male or firstborn [24,25]. Therefore, a child’s personal attributes can systematically shape how willing parents are to support costly education-related migration decisions.

2.2.2. Migration Capacity

- (1)

- When family income is higher ;

- (2)

- When the cost of rural–urban student migration is lower .

- (1)

- The impact of family resource endowment on migration capacity: Family resource endowment can influence , consequently affecting migration capacity. Firstly, total family income directly represents . The higher the family income, the stronger the migration capacity. Secondly, the family income of rural households includes wage income, property income, business income, and transfer income. The number of laborers in the family affects wage income, while the cultivated land area affects business income or property income. Therefore, the greater the number of family laborers and the larger the cultivated land area, the stronger the migration capacity.

- (2)

- The impact of parental individual endowment on migration capacity: Parental individual endowment can influence and , consequently affecting migration capacity. Firstly, the parental level of education, occupation type, workplace, and personal annual income can influence . Personal annual income directly contributes to total family income, and the individual’s level of education, occupation type, and workplace indirectly contribute to total family income by influencing personal annual income. Generally, individuals with higher education, those employed in white-collar occupations, or those working in urban areas tend to have higher personal incomes. Secondly, the parents’ workplaces can also influence migration capacity by affecting . When the parents’ workplaces are in the city, their offspring are more likely to meet the enrollment conditions for urban migrant workers, which reduces the cost of rural–urban student migration.

3. Empirical Research Design

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Econometric Model Setting

3.4. Variable Selection

3.4.1. Dependent Variables: Migration Willingness and Migration Capacity

3.4.2. Explanatory Variables

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Driving Factors Influencing Rural–Urban Student Migration Decisions

4.1.1. Influence of Family Resource Endowment

4.1.2. Influence of Parent’s Personal Endowment

4.1.3. Influence of Student Individual Characteristics

4.1.4. Influence of Other Factors

4.2. Mechanisms of Rural–Urban Student Migration Decision-Making

4.2.1. Formation Mechanism of Rural Households’ Migration Willingness

4.2.2. Mechanism of Formation of Rural Households’ Migration Capacity

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewis, W.A. Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour. Manch. Sch. 1954, 22, 139–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J. Dual economy models: A primer for growth economists. Manch. Sch. 2005, 73, 435–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wu, X. Separate and Unequal: Hukou, School Segregation, and Educational Inequality in Urban China. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 2022, 54, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, A.; Tang, B.; Shi, Y.; Tang, J.; Shang, G.; Medina, A.; Rozelle, S. Rural Education across China’s 40 Years of Reform: Past Successes and Future Challenges. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2018, 10, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, Y. Return Migration of Rural-Urban Migrant Children in China. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2024, 43, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Ren, Y. Children of Migrants in China in the Twenty-First Century: Trends, Living Arrangements, Age-Gender Structure, and Geography. In Children of Migrants in China: Living Arrangements, Care and Education; Chan, K.W., Ren, Y., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Brauw, A.; Giles, J. Migrant Opportunity and the Educational Attainment of Youth in Rural China. J. Hum. Resour. 2017, 52, 272–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kao, G.; Hannum, E. Opportunity or New Poverty Trap: Rural-Urban Education Disparity and Internal Migration in China. China Econ. Rev. 2017, 44, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Lv, L.; Wang, Z. Research on Left-behind Children’s Home Education and School Education. Peking. Univ. Educ. Rev. 2014, 12, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Wu, L.; Zuo, W.; Li, S. From Industrial Urbanization, Land Urbanization to People-centered Urbanization: A Sociological Investigation on the Chinese Pathway to Urbanization. J. Soc. Dev. 2018, 5, 42–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Haeringer, G.; Klijn, F. Constrained School Choice. J. Econ. Theory 2009, 144, 1921–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, C.; Hillyard, S. School Choice in an English Village: Living, Loyalty and Leaving. Ethnogr. Educ. 2015, 10, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Clark, G. Parental Choice and the Rural Primary School: Lifestyle, Locality and Loyalty. J. Rural. Stud. 2010, 26, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.; Liu, C.; Luo, R.; Zhang, L.; Ma, X.; Bai, Y.; Sharbono, B.; Rozelle, S. The Education of China’s Migrant Children: The Missing Link in China’s Education System. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2014, 37, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Xu, L. Research on Rural Migrant Workers’ Selection of Location for Their Children’s Education and Its Influence Factors—Under the Background of Urbanization. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2016, 55, 150–158. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Liang, Z. A Comparative Study of Parental Migration Decision for Children of Two Generations of Floating Population in China. Popul. J. 2019, 41, 77–90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yue, Z. Parental Migration, Children and Family Reunification in China. Popul. Space Place 2023, 29, e2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Wei, Y. Two Systems in One Country: The Origin, Functions, and Mechanisms of the Rural–Urban Dual System in China. In Urban China Reframed: Competition, Integration, and Governance; Wei, Y.D., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 82–114. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, P.E.; Wolpin, K.I. On the Specification and Estimation of the Production Function for Cognitive Achievement. Econ. J. 2003, 113, F3–F33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M. Family Stretching between Town and Country: Infrastructure, Spatio-Temporal Experience and Urban-Rural Relations at the County Level Revisited. Sociol. Stud. 2021, 36, 45–67. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Waithaka, E.N. Family Capital: Conceptual Model to Unpack the Intergenerational Transfer of Advantage in Transitions to Adulthood. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014, 24, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Jin, M.; Zeng, L.; Tian, Y. The Effects of Parental Migrant Work Experience on Labor Market Performance of Rural-Urban Migrants: Evidence from China. Land 2022, 11, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, S.; Laing, S.K.; Higgins, C.R.; Yemeke, T.T.; Park, C.C.; Carlson, R.; Ko, Y.E.; Guterman, L.B.; Omer, S.B. Educational and Economic Returns to Cognitive Ability in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. World Dev. 2022, 149, 105668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannum, E. Market Transition, Educational Disparities, and Family Strategies in Rural China: New Evidence on Gender Stratification and Development. Demography 2005, 43, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, M. Birth Order, Family Size and Educational Attainment. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2010, 29, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, A.; Jæger, M.M. Dealing with Selection Bias in Educational Transition Models: The Bivariate Probit Selection Model. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2011, 29, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Long, H.; Qiao, W.; Wang, Z.; Sun, D.; Yang, R. Effects of Rural–Urban Migration on Agricultural Transformation: A Case of Yucheng City, China. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 76, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.-J.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.-C.; Yip, C.K. To Stay or to Migrate? When Becker Meets Harris-Todaro; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lalive, R.; Cattaneo, M.A. Social Interactions and Schooling Decisions. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2009, 91, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selod, H.; Shilpi, F. Rural-Urban Migration in Developing Countries: Lessons from the Literature. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2021, 91, 103713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biblarz, T.J.; Stacey, J. How Does the Gender of Parents Matter? J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Sun, Y.; Xing, C. Son Preference and Human Capital Investment among China’s Rural-Urban Migrant Households. J. Dev. Stud. 2021, 57, 2077–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Brown, D.S.; Zheng, X.; Yang, H. Women’s Off-Farm Work Participation and Son Preference in Rural China. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2022, 41, 899–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S.; Lewis, H.G. On the Interaction between the Quantity and Quality of Children. J. Political Econ. 1973, 81, S279–S288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiner, D.L.; Godwin, J.; Dodge, K.A. Predicting Academic Achievement and Attainment: The Contribution of Early Academic Skills, Attention Difficulties, and Social Competence. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 45, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kao, G.; Hannum, E. Do Mothers in Rural China Practice Gender Equality in Educational Aspirations for Their Children? Comp. Educ. Rev. 2007, 51, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lépine, A.; Strobl, E. The Effect of Women’s Bargaining Power on Child Nutrition in Rural Senegal. World Dev. 2013, 45, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X. Cultural Capital and Gender Differences in Parental Involvement in Children’s Schooling and Higher Education Choice in China. Gend. Educ. 2012, 24, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Migration Willingness | Migration Capacity | |

| Family annual income | −0.0005 | 0.0236 ** |

| (0.0085) | (0.0102) | |

| Number of laborers | 0.0149 | 0.0264 |

| (0.0526) | (0.0554) | |

| Arable land area | 0.0067 | 0.1125 ** |

| (0.0380) | (0.0463) | |

| Father’s education level | 0.0070 | 0.0061 |

| (0.0275) | (0.0301) | |

| Mother’s education level | 0.0471 * | 0.0039 |

| (0.0268) | (0.0281) | |

| Father’s workplace (with rural areas as a reference) | ||

| Urban areas inside the county | 0.1032 | 0.2277 |

| (0.1807) | (0.1965) | |

| Urban areas outside the county | −0.2099 | 0.0054 |

| (0.1649) | (0.1575) | |

| Mother’s workplace (with rural areas as a reference) | ||

| Urban areas inside the county | 1.3566 *** | 0.5936 *** |

| (0.1766) | (0.1852) | |

| Urban areas outside the county | 0.1590 | 0.4299 ** |

| (0.1920) | (0.1993) | |

| Father’s occupation type (with unemployment as a reference) | ||

| Farmer | −0.6196 ** | 0.3743 |

| (0.2560) | (0.2539) | |

| Blue-collar worker | −0.3588 | 0.6857 *** |

| (0.2680) | (0.2482) | |

| White-collar worker | 0.2059 | 0.9972 ** |

| (0.4076) | (0.4309) | |

| Individual business owner | 0.3183 | 0.7449 ** |

| (0.3540) | (0.3551) | |

| Mother’s occupation type (with unemployment as a reference) | ||

| Farmer | −0.2993 | 0.0109 |

| (0.1891) | (0.1953) | |

| Blue-collar worker | 0.1036 | 0.1986 |

| (0.2046) | (0.2174) | |

| White-collar worker | 0.7989 ** | 0.5639 |

| (0.3458) | (0.3790) | |

| Individual business owner | −0.1763 | 0.6627 * |

| (0.3626) | (0.3712) | |

| Father’s annual income | 0.0177 | 0.0475 * |

| (0.0249) | (0.0266) | |

| Mother’s annual income | 0.0624 ** | 0.0190 |

| (0.0282) | (0.0266) | |

| Student’s gender | 0.0042 | −0.1479 |

| (0.1161) | (0.1195) | |

| Student’s age | −0.0815 *** | 0.0083 |

| (0.0238) | (0.0233) | |

| Student’s birth order | −0.1489 ** | 0.0299 |

| (0.0712) | (0.0748) | |

| Student’s learning talent | −0.1318 ** | −0.0938 |

| (0.0565) | (0.0603) | |

| Educational values | 0.0807 | −0.0428 |

| (0.0915) | (0.0909) | |

| Same-group migration rate | 1.4150 *** | |

| (0.2260) | ||

| Regional fixed effects | Controlled | Controlled |

| Constant | −0.3287 | 6.8300 |

| (0.4625) | (11.0000) | |

| Observations | 916 | 916 |

| Wald chi2 | 15.2156 *** | |

| athrho | −0.3182 *** | |

| (0.0816) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, R.; Qiao, H.; Wei, J.; Zheng, F. To Stay or to Migrate: Driving Factors and Formation Mechanisms of Rural Households’ Decisions Regarding Rural–Urban Student Migration in China. Societies 2025, 15, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080226

Wang R, Qiao H, Wei J, Zheng F. To Stay or to Migrate: Driving Factors and Formation Mechanisms of Rural Households’ Decisions Regarding Rural–Urban Student Migration in China. Societies. 2025; 15(8):226. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080226

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ruonan, Hui Qiao, Jinyang Wei, and Fengtian Zheng. 2025. "To Stay or to Migrate: Driving Factors and Formation Mechanisms of Rural Households’ Decisions Regarding Rural–Urban Student Migration in China" Societies 15, no. 8: 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080226

APA StyleWang, R., Qiao, H., Wei, J., & Zheng, F. (2025). To Stay or to Migrate: Driving Factors and Formation Mechanisms of Rural Households’ Decisions Regarding Rural–Urban Student Migration in China. Societies, 15(8), 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080226