Abstract

Highway construction in China has bolstered Chinese claims of having the longest highways in the world, yet it has led to the involuntary relocation and resettlement of millions of people all over China. This study examines the interplay of power relationships in modernity and ethnic cultures. Using interviews with 201 Zhuang ethnic minority people and participant observations from two years in the Southwest of China, this paper presents findings that show both the positive and negative effects of urbanization and modernization as the consequence of highway expansion. By discussing the removal of a religious Sacred Rock which was in the way of the highway construction, the authors reveal the subtleties of the power interplay of majority–minority relations and the meanings of cultures and rituals in the face of modernity. In the process of modernization, highway construction reconstructs new communities while deconstructing the old one. The authors argue that recognizing the meanings of ethnic cultures as defined by ethnic people themselves is the first step to the reconciliation of social relationships between the majority and minority people in created new communities. To enhance social integration, religion has an important role to play in Chinese society.

1. Introduction

Fighting for ethnic cultural recognition and legitimacy against the rapid pace of China’s modernization is a story that receives little attention in or outside the Chinese border. To what extent an ethnic minority have a voice and make this voice heard in mainstream society demonstrates the fundamental rights of the ethnic community. This ongoing interaction of majority and minority relations goes beyond the borders of China and is continuing in the U.S. and Canada. On 17 July 2016, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in Dakota filed a complaint in the U.S. district court of the District of Columbia against the federal government’s construction and operation of the Dakota Access Pipeline which “threatens the Tribe’s environmental and economic well-being, and would damage and destroy sites of great historic, religious, and cultural significance of the Tribe.” [1].

The U.S. and Canada recognize 562 culturally, ethnically, and linguistically different Native American tribes. The Native American Indians’ civil rights are protected by the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. In its expression of religious freedom, the First Amendment recognizes the Sacred Stones, such as “the Painted Rock—Idols of the Holy Stone”, which have been revered by the Cheyenne and Sioux for hundreds of years [2]. The Native Americans would place offerings in front of the Sacred Stone, praying for good food, safe travels, and a long life. Similarly, some ethnic Chinese groups recognize Sacred Rocks and perform rituals in front of the Sacred Rocks recognized by the native ethnic people. Yet, when highway expansion in the process of modernization penetrates remote regions of China, modernity and traditional customs collide—some Sacred Rocks may be deemed “in the way” of modernization.

Highway construction was an important expression of “high modernity” in the 1950s in the U.S. In 1956, President Eisenhower signed the “Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956” into law, funding 90% of interstate highway construction [3]. In its drive toward modernization, China started its construction of the National Highway Systems in 1986, building its first highway from Beijing to Tianjin. In the 2000s, highway construction reached a higher level across China. By 2019, China was leading the world with the longest expressway, at 149,600 Km [4]. With the rapid construction of highways in China, thousands and millions of people had to be relocated and resettled. Communities are removed, and cultures and traditions are disrupted or abandoned. This paper aims to increase the understanding of the interplay of modernity and ethnic cultures in the process of urbanization and modernization. Using participant observation and on-site interviews with local cadres, residents, and elders, this study sheds light on how highway construction disrupted local cultures and communities. In this process, the authors reveal the power of knowledge and control, the definition of legitimate cultures, and the subjugation of ethnic cultures. In the space below, we will first review the relevant literature on issues related to modernity and resettlement, majority–minority relations, and the meanings of the legitimacy of cultures. Then, we will present our research site and method for the study. Using qualitative methods, we will present our findings extracted from our interviews and participant observations. Finally, we will integrate our findings with the prior literature in the Discussion section.

2. Literature Background

2.1. Modernity and Resettlement

In the article, “People in the Way: Modernity, environment and society on the Arrow Lakes,” [5]. Loo examined the creation of British Columbia through hydroelectric development in post WWII Canada. It is one of the large-scale, state-directed environmental exploitations in which governments “sought to deliver social benefits to particular groups by compelling them to move,” because these groups of people were “in the way” of the government’s endeavor toward modernity. From the perspective of “high modernist planning,” Loo pointed out that “state-sponsored forced migration was simply a more systemic approach to a strategy adopted by generations of people who had to move to better their conditions” [5] (p. 5). While high modernity in Canada and the U.S. happened half a century ago, it is an ongoing process currently in China.

From 1950 to 2000, 40–80 million people had to move and resettle in China because of dam construction; the most well-known resettlement is related to the construction of the Three-Gorge dam [6]. Similarly, for the construction of highways reaching all over the country and beyond, millions of people had to move involuntarily and be resettled. Even though some social science research has shown that highway or dam construction has sped up the process of modernization, diversified migrant workers’ employment, improved some residents’ living conditions, and increased migrant workers’ income overall, other studies, however, found long term negative impacts on local people due to land appropriation, dam building, and highway construction [7,8]. Huang et al., based on their study of the Three-Gorge dam resettlement, revealed that former farmers became landless and homeless, while migrant workers became urban-jobless. By 2017, dam-induced displacement and resettlement had shown negative impacts on employment, income level, and income sources. “Many residents suffered from disruption of livelihood,” and resettlement “reduced life satisfaction” [6] (p. 14).

Presumably, highway construction would bring more convenience in transportation and greater access to urban areas for people living in remote or rural areas. Research findings showed the opposite in some locations. Zhu and Hu [9] found that local people residing in mountainous regions of Yunnan Province reported they felt more segregated after the highway construction because the highways were not accessible to the local people, as there was no exit to their mountainous region. The highway became the “other” entity which created new segregation. Former neighbors became distant and estranged because the local people must travel several kilometers to detour around the newly built expressway to visit a former neighbor whose house may be located just a few hundred yards away on the other side of the highway.

The highway construction from China to Tajikistan is another good example. The road can be both an “enabling” and a “limiting” factor in mobility [10]. A year after the road was completed linking China to Tajikistan in the Eastern Pamirs, the Chinese government required citizens in Tajikistan to obtain a Chinese visa from over 1500 km away in Urumchi, the capital city of Xianjiang, by air to travel across the border to China, which can be as close as only a few miles away by land. In the meantime, Chinese businessmen could drive straight into Tajikistan for any trade or business. Consequently, the road has enabled China’s penetration into Tajikistan, while it has limited the access of the local people in Tajikistan to trade across the Chinese border.

Foucault [11] (p. 252) said, “Space is fundamental in any exercise of power.” Following his well-known books Discipline and Punish and History of Sexuality, Foucault expanded his philosophical analysis to the relationships between space, knowledge, and power. He contends that space is not just natural geographic spaces for people to live and reside, it is power and control over races and cultures [12]. Since the emergence of urban planning in the 18th century, the governmentality of peopled spaces has become a key domain of political power for the “maintenance of order, avoidance of epidemics and revolts, and permitting decent and moral family life” [13]. In the process, knowledge is power. Local knowledges and their “subjugation” result in “an uneven geography” of knowledge about society [12] (p. 12).

From the U.S. government’s take-over of Native American Indian territory to the “state-sponsored forced migration” in British Columbia, power is exercised, whether by force or under the disguise of “social benefit” to the people. In its effort to achieve modernization, elimination of poverty, and environmental protection, the Chinese government is exerting its power and control “for the benefit of the Chinese people.” When modernization or highway construction projects reach minority territory, the power of the Chinese government to deliver “social benefit” is further enacted and demonstrated.

2.2. Resettlement and Minority Relations

In 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court decided to return more than 3 million acres of land in Oklahoma to a Native American Muscogee (Creek) Nation [14]. For centuries, the U.S. government have taken over Native American Indians’ land and properties either by force or by an unfair “market mechanism” to accomplish “nonconsensual alienation of indigenous lands” [15] (p. 72). The land dispute, as shown in the recent U.S. Supreme Court decision, continues today. China is a nation with an 82% Han majority population. Fifty-six other different ethnic minorities make up 18% of China’s population. Among the minority population, the well-known ethnic groups include the Tibetans living in Tibet and the Uyghurs living in the Western part of Xiangjiang, China. In recent decades, the environmental protection movement has called for environmental resettlement to avoid further soil erosion in some areas of Tibet. Tens of thousands of Tibetans have been mobilized to move and resettle in different areas of China.

The process of resettlement carried on “with various degrees of consent and coercion,” in a “complex interplay of interest and power relations” [16] (p. 731). The resettlement of Tibetan people in the Aba autonomous region, in the “Grand Development in West China,” was a good example of the majority and minority relations in China. Tan noted that resettlers in Tibet were given “inadequate right of participation and options in the process of their displacement and resettlement” [17] (p. 631).

Similarly, Gongbo and Foggin [18] revealed that the resettlement was designed by the government with little understanding of local Tibetan people’s lifestyles. Houses were designed by the Han architect with mainstream notions of lifestyles without consideration of animal husbandry. Once resettled, Tibetans could no longer herd animals or live the life they used to. Furthermore, insufficient consultation and interaction with local people led to “insufficient community ownership and cultural awareness”. While the Chinese central government probably started with the noble goal of “delivering the social benefit” of alleviating poverty in the ecological resettlement project, in the end, the government fell short of reaching its goal. Tibetan people lost their way of life and their sense of stability and community because they had limited education and little agricultural experience. Once resettled, they became low-wage construction workers or unstable, low-wage employees.

Bai [19], in his study of the resettlement process of Yunan Wa ethnic people, documented the mismatch of modernity and ethnic cultures and customs. For “better”-quality living conditions, the local government decided to uniformly use brick and mortar in replace of the local thatched cottages for relocated residents. However, during the June to October rainy season in this area, the poorly constructed brick-and-mortar houses could not withstand the sustained rainy season. Water leakage was a problem in every house. The Wa ethnic minority people lived in misery due to the constant struggle against mold in everything, spoiled food, and wet clothing inside the house.

Decker [20] studied the dislocation of the Li ethnic minority in Hainan Island, China. Using site visits and interviews, Decker noted that resettlement was “engineered through local government and party agencies which excluded participation of an independent civil society” [20] (p. 128). In the process of the resettlement, “houses were assigned on the basis of the size of a nuclear family” with little consideration of kinship and friendship networks in the traditional village [20] (p. 136). Consequently, there were “weakened kinship ties and numerous social pathologies such as alcohol abuse and depression” [20] (p. 128).

In their study of environmental resettlement in Inner Mongolia, Rogers and Wang used field trips and interviews to understand the context and impacts of resettlement on Mongolian people [21]. To reduce sand and dust storms, which originated in Inner Mongolia and swept all the way to Beijing, the Chinese government initiated the environmental resettlement of 650,000 people from inner Mongolia to other regions of China to reach the “ecological objective of returning 6 million Chinese acre of agricultural land and 2 million Chinese acre of pastoral land ‘to nature’” [21] (p. 46). Resettlers experienced a degree of “social disarticulation.” Many missed their old village, the fluid social relations, and the place where they felt a sense of belonging because the “place attachment” gave them a sense of “daily and ongoing security” in their lives, “fostering and sustaining a group’s identity” [21] (p. 59). Some scholars have pointed out that the existing resettlement policies often emphasized moving people and providing “hardware”, such as monetary compensation, houses, roads, and schools, but neglected facilitating software—the social integration of settlers with locals [22,23].

2.3. Modernity and Cultures

Fei [24] criticized the prevailing tendency in China to treat any “traditional culture” as the “enemy” of modernization. In the push to alleviate poverty, to increase environmental protections, and to generate greater resources, environmental resettlement and dam or highway construction-related resettlements have subjugated the survival of some ethnic cultural heritages. Urbanization is a key factor that assimilates minorities into the majority culture. Some scholars argue that minority cultures that are not adaptive to China’s urbanization are bound to be left behind or abandoned [25,26]. Others contend, rather, that it is the majority power that absorbed the minority culture into the process of modernization—the minorities barely had any choice [27,28].

Different perceptions of knowledge and cultures co-exist not just inside China. In Iceland, for instance, highway construction was “scuppered” in 2015 because of the fear of disturbing the “huldufolk”, or hidden people of the elves, who “stand for living in harmony with nature” [29,30]. In 2016, Iceland construction workers had to unearth a rock that they accidentally buried to appease angry elves [31]. In both cases, though, these fictional or fairy-like elves were believed to be true or real people by the locals. The knowledges held between the locals and the government or construction companies were negotiated, and road construction had to halt or re-route.

Durkheim emphasized the important role of rituals and religions in The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Shared beliefs and values create a collective consciousness which binds people together. When people share common history and religious rituals together, they are more likely to share greater levels of social integration and harmony. “Religion is something essentially social…social life depends upon its material foundation and bears its mark…” [32] (p. 92). In the process of modernization and urbanization, traditional and religious symbols and practices in China are often seen as “feudal and backward” customs deserving reformation and abandonment.

Bai [19] noted that the practice of geomancy or fengshui in the construction of new thatched homes among the Yunan Wa ethnic group in Southwest China was an important part of community cultural ritual. Neighbors used to help each other to build a new house. On the day of house completion, all community members would sit around an outdoor bonfire and sing folk songs and share community legends and folk stories. Every 5–6 years, each family would rebuild their thatched cottage with the help of the community—all people shared the event and the collective history and memory together. When involuntary resettlement happened, this ritual was abandoned. The Wa people were assigned to live in modern brick houses designed and built by the government and the majority architects, not by the ethnic community. After the Wa people moved in, these modern houses never stopped leaking in rainy reasons. Whether it was due to the poor-quality brick-and-mortar houses or the abandonment of fengshui, the ethnic Wa people and the majority Han people in China, of course, would offer completely different explanations.

Li told the story of “ancestors moving into the city” in resettlement. Ancestor worship is an important part of Confucian as well as Chinese Muslim cultural practice [33]. When the whole Zhang village had to be relocated, their ancestors’ tombs had to be moved. While the living residents were moving to the “Yang” residential site, the villagers perceived the new site of the ancestors’ tombs to be the “Ying” residence of their ancestors. The older villagers said, “When we move to a city surrounded by sky-scrappers, our ancestors will be moved to a public cemetery, just like our living quarters, surrounded by strangers.” These religious sentiments could have been treated as “backward” or traditional ideas and been dismissed. However, when community members were united, they made their voices heard. In the Zhang village, their concerns for their ancestral tomb’s relocation were respected.

The revival of a Muslim Mosque is another example of renewed recognition for the protection of ethnic and religious heritage in the process of China’s urbanization. Zhou [34] noted that the collective efforts of organization, protection, and resistance saved a community with individual houses and temples which dated back to the Ming (1400–1600 AD) and Qing (1650–1900) dynasty. The mosque near Wuhan City, Hubei Province, named Majiazhuang Mosque, was originally built at the end of the Qing dynasty. It was destroyed by the Japanese during WWII in 1938. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Mosque was rebuilt, only to be destroyed again during the Cultural Revolution. Upon repeated requests from Muslim residents, the government decided to rehabilitate the local Muslim Culture Activity Center and rename it the “Majiazhuang Village Mosque.”

The previous literature has provided evidence that China’s rapid processes of modernization and environmental resettlement have brought both positive and negative effects into the lives of local people and resettlers. There have been more studies on the material well-being and impact of dam or highway construction. Rarely do scholars pay attention to ethnic cultures and symbols or to the meanings and importance of these symbols to the ethnic people themselves. This study adds to the literature by presenting the images, voices, and sentiments from one ethnic group—the Zhuang people themselves—to demonstrate the interplay of power, space, and cultures in the push toward modernization and highway expansion in China.

3. Research Method and Study Site

3.1. Sample Site

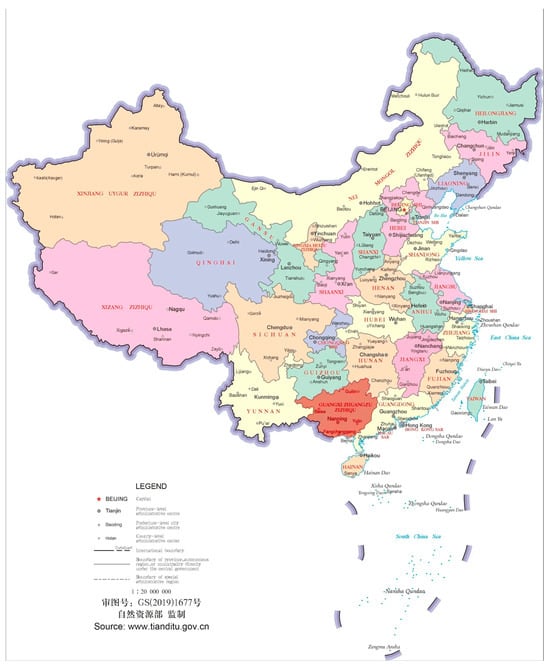

The site for this study is in Huang village, M County, Guangxi Zhuang Ethnic Autonomous Region, which is like a Province in terms of its administrative function. Guangxi is in Southwest China, bordering Vietnam (see its location in the map of China below in Figure 1). The geographic size of Guangxi covers 237.6 square km, like the size of Colorado in the U.S. M County is in the central west part of the province. Huang village is in central east M County. M County had a total population of 574,400 people in 2019 and 81.42% of its population was registered as “rural” residents. Among the rural residents, 18.5% migrated to urban areas to make a living. M County is a region with many ethnic residents. The Zhuang ethnic group is the majority in terms of population in this County, followed by Han people (the national majority) and Yao people. There are also 11 other ethnic peoples, including Miao, Tong, Sui, Yi, Li, Tujia, and more. Each ethnic group uses their own language for communication among themselves, but they all use Mandarin when communicating outside their ethnic group.

Figure 1.

The location of Guangxi Zhuang Ethnic Autonomous Region (in dark red color) in the map of China. Other colors are only meant to differentiate provincial boundaries.

Huang village, where the sample is drawn from at the time of the highway con-struction, is in the central east of M County. It is 120 km from Nanning City, the capital of Guangxi. The village occupies a space of 36 square km in size. It is in the subtropical zone, with 1660 mm of rainfall per year. Rice, corn, sugarcane, peanuts, soybeans, and longan (dragon eye, like lychee) are major agricultural products in the region. The Farmer’s Market opens twice a week.

There were 3450 residents in 900 family households in Huang village. Zhuang ethnic people were 95% of its population at the time of the study. There were 2616.25 Chinese acres (mu) of arable land (1 acre = 6.07 mu, roughly 431 acres) and 636.47 Chinese mu (or 104 acres) were used for growing rice. Additionally, 1979.78 mu (326 acres) were dry land for other agricultural production. Based on the 2015 M County Civic Economic Development Report in 2015, on average, local farmers in the county had an annual income of 6664 RMB and an average annual expenditure of 6225 RMB—this was shown to be a 12.53% increase from the past year.

Setting the general goal of building highways through Guangxi to reach the port of the South China Sea, the Chinese central government started an inter-provincial highway in the 1990s. By 2020, highway construction had reached 5590 km in Guangxi Province. Highway G75 is just one of these projects. The construction of Highway G75 affected 201 families and 1005 people in the Huang village. Among them, 116 families were uniformly arranged and resettled by the government. Eighty-five families accepted resettlement compensation and moved and relocated by themselves. A total of 580 people were resettled by the government, and 415 people were relocated by themselves. In the process of highway construction, 266.21 Chinese mu (43.86 acres) of arable land was taken, 142 of which used to be used for rice production, and 124.21 for other agricultural production. The standard compensation for each Chinese mu of arable land was 36,010 RBM (roughly USD 5142).

3.2. The Ethnic Cultures and Religions

Even though the people living in mainland China are commonly known as the “Chinese” to people outside China, there are 56 ethnic groups among the Chinese people. The Han are the majority, accounting for 82% of the total population in China. Fifty-five other ethnic minority groups make up the remaining 18% of the Chinese total population. Among the ethnic minority groups, the Zhuang ethnic minority has the largest population. According to the sixth Chinese national census in 2010, there were a total of 16,926,381 Zhuang people listed, occupying 12.7% of China’s total population in that year. In Guangxi Province, where this study is performed, the Han majority people account for 62.86% of the population, while the Zhuang people account for 37% of its population. Zhuang ethnic people mainly reside in Southern China, including in Guangdong, Yunnan, Guizhou, and Guangxi Provinces. In Guangxi Province, the Zhuang people live near Vietnam. There are language, custom, and cultural similarities between the Zhuang ethnic people in China and several ethnic groups in Vietnam.

The Zhuang ethnic people have their own language. Over a third (35.52%) of the people in Guangxi Province speak the Zhuang language, ranking as the third most frequently used language after Mandarin. The Zhuang language shares similarities with languages in Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam. Outside China, people refer to the Zhuang language as “the Northern Thai” language. The Zhuang language has both written and spoken components. The written language can be traced to the Shang (1600 BC to 1000 BC) and Warring States (475 BC to 221 BC). After the first Emperor Qin unified China, Mandarin became a national language, and the written form of Zhuang faded from the mainstream. However, the actual practice and use of the Zhuang language continued in the Tang and Song dynasties. Its written language is a combination of pictogram, ideogram, and phonogram.

The Zhuang people in Guangxi Province reside in mountainous regions. Their livelihood relies on the production of rice and other agricultural products. Nature worship is part of their religious beliefs. Behind the sun, rain, and thunder, the Zhuang people believe there are sacred forces dominating their lives. In addition, they also practice ancestry worship. They believe that the souls of their ancestors remain alive, protecting their posterity.

Women play a central role in religious practices. Shamans are all female. There is no male shaman. Marriage is matrilocal. After the marriage ceremony, according to their custom, the bride usually returns to her natal village to reside. She only pays visits to her groom’s family. Pre-marital unions at ages 15 to 16 are a common practice in Zhuang customs. Once this union results in pregnancy, then a marriage is complete. Brides remain in their own natal family.

3.3. The Sacred Rock

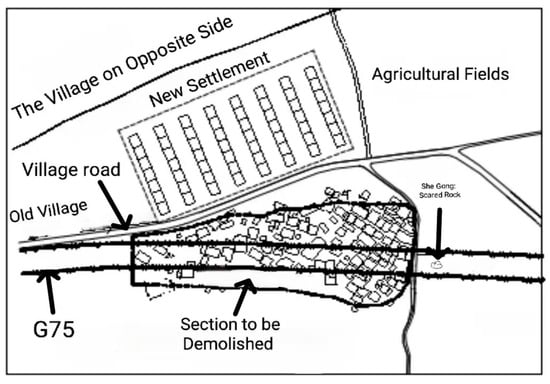

In Huang village, 98% of the residents are of the Zhuang ethnicity. The Zhuang residents in the village have four designated Sacred Rocks, located in the four corners of the village. The Sacred Rock that was in the southeast corner of the village happened to be “in the way” of the G75 Highway (See Figure 2 for its image). To push the highway forward, the local government believed that it had to be removed by explosives. According to the villager Mr. Huang, this Sacred Rock has been designated “Sacred” for over 200 years by villagers. The name of the Sacred Rock is “She Gong”; its literal translation is “Community Deity”. In Zhuang culture, a rock that is shaped straight upright or like a human body is often selected as a community deity [35]. It is believed to protect the Zhuang people in the village by driving away demons. On major memorial days, such as Cleansing Day on February 7 in the Lunar calendar, when people go to visit their deceased relatives; March 3, when villagers celebrate the coming of the spring; and every Chinese New Year, when villagers celebrate the renewal of life, all villagers would bring sacrificial goods to pray for protection from the Sacred Rocks. Sacred Rocks are believed to provide good fengshui or geomancy for the villagers.

Figure 2.

Sacred Rock image.

The importance of these Sacred Rocks for villagers is evident. At the time of the highway construction, the villagers organized a committee to try to save the Sacred Rock by negotiating with the government and highway construction companies. But both the government and construction companies insisted that the G75 could not be re-routed. The reason was that the Sacred Rock recognized by the local people was not recognized by the Chinese government, dominated by the Han people. Only government-identified cultural heritage sites may avoid being removed by explosives. For instance, one ancient tree, dating back to the Ming dynasty (prior to the 1640s) was considered a cultural heritage site. In that case, the highway was re-routed to avoid cutting down or removing the tree. The Sacred Rock, though sacred for the local Zhuang people, was not recognized as cultural heritage by the government or majority culture. Worshiping a rock was considered “superstitious” by the highway engineers and local government officials. Superstitious practices were not encouraged; some were suppressed or persecuted, such as Falungong [36]. Relocating the Sacred Rock was considered by the villagers, but no practical proposal for its relocation was brought up. With little financial resources and no support from the local government, the Zhuang people had no concrete resolution to save or relocate the Sacred Rock. All they could accomplish was to negotiate monetary compensation. In the end, the villagers were compensated 200,000 RMB (roughly USD 3000) for the Sacred Rock. The Sacred Rock was eliminated using explosives.

3.4. The Study Procedure

The first author of this study conducted field research from October of 2012 to May of 2016. From fall of 2013 to October of 2015, the senior researcher lived on-site every day, conducting face-to-face interviews and participating in local village activities. Access to the population was obtained from a family relative who was married into the Zhuang ethnic community. As an extended family member, the interviewer was trusted. Interviews included all 201 families who had to relocate because of Highway G75’s construction. At least one member of each family was included in the interviews. Sometimes, several members participated in the study, but one key informant was selected. Below is the table of the sample characteristics of the study participants (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n = 201).

Among the interviewed 201 participants, 112 (56%) were male and 89 were female. The age range of the informants included half (51.9%) under age 45. Roughly a quarter (25.7%) of the interviewees were between ages 46 and 60 and over one-fifth (22.4%) of the interviewees were 61 and over. Nearly a quarter of the informants (24.1%) in the village had no formal education. Roughly a third (31.8%) had elementary school (1–6 years) education. Over a third (35.8) received a junior high school education. Only 8% (or 16) of the participants had high school or higher education. Among them, only eight people received college education. Most families (74.6%) in the Zhuang village had more than two children. Most families lived in extended-family households. Twenty interviewees (10%) lived in a skipped-generation family, i.e., the adult children were migrant laborers while the grandparents were taking care of the grandchildren without the parents present.

Prior to the highway construction, over half (55.6%) reported to be agricultural farmers. Eighteen percent raised animals for a living and eleven participants (5.6%) reported working in forestry. After the highway construction, farming, animal husbandry, and forestry were all reduced. Migrant workers dramatically increased from 17% to 46.77% among the 201 families.

3.5. Data Collection

Field research allows researchers to “develop a deeper and fuller understanding” of an event or process. It defies simple quantification and recognizes “nuances of attitude and behavior that may escape researchers using other methods” [37]. Using field research by participant observation and intensive interviews were most appropriate for this study because the goal of the research was to understand the meanings of cultural symbols to ethnic communities and the impact of highway construction and resettlement on these communities. Data for this paper was collected from intensive interviews and participant observations. Intensive interviews lasted from 30 min to over 2 h. They were tape-recorded and later transcribed into Chinese verbatim. The Chinese transcription accounted for over 230,000 Chinese characters, over 200 pages in length. Most interviews were conducted in Chinese Mandarin because most Zhuang people speak Mandarin. When an interviewee was over 60, an interpreter was hired to translate from the Zhuang language to Mandarin because older Zhuang people generally did not receive formal education and they did not speak much Mandarin, or only a few words. The interview guide was approved by Hohai University, China. Ethical approval was obtained from Hohai University in 2014 (2014B09714). Participants’ confidentiality was ensured by creating case numbers and pseudonyms. Oral consent was obtained before each interview started. Anonymity was strictly enforced to protect the identity and safety of the ethnic minority group. To ensure confidentiality, we used pseudonyms not just for interviewees, but for the village and the county. Data is in Chinese and can be made available upon request.

3.6. Data Analysis

After reviewing the interviews verbatim, we started word-for-word coding. We tried to ground our coding on the verbatim Chinese. Using grounded theory as our guiding principle [38], we grounded our understanding of the impact of highway construction by identifying various concepts as the first step. With reoccurring concepts, we started to generate categories in the second level of abstraction. Then, we developed themes. For this paper, we focus on the three reoccurring themes of livelihood, culture, and social integration as the core study findings related to the impact of Highway G75’s construction.

4. Findings

Huang village is in the valley of the mountainous regions of Guangxi. There is limited arable land for rice, corn, and other products. With the highway cutting across the center of the village, taking most of the arable land, residents had to be relocated from their former dwellings to rice paddies or corn fields. The livelihood of the villagers was dramatically ruptured and reduced. A former farmer accounted the following:

“Before the highway construction, we grew rice, sweet potato, soybean, lotus roots, and tapioca, all for our own consumption. But we were self-sufficient. In some areas, if a family had fewer mu (Chinese acre) of land, they might have grown corn. Most families would raise a water buffalo or two for ploughing. There was little machinery used here because of the mountainous and rocky landscape. Water buffaloes are important; they are important for ploughing the land. Some families raised horse and sheep”.(Mr. Mo, age 52)

Another farmer shared the same concern for the lack of self-sufficient arable land. Mr. Lan said:

“We used to have enough to eat. At least we didn’t have to worry about food. Now we don’t. We must purchase food. Food prices are expensive. We cannot afford it. We try to compensate our cost of living by doing a little small business on the side, but you cannot depend on it. Earnings from businesses cannot fundamentally solve our problem. To some extent, we are now not as good as before we relocated.”

Interestingly, the New Communist Party Secretary of the village had a very positive view of post relocation status. He said:

“Currently, we have 15 farming machinery to help with ploughing, planting, and harvesting. The speed of the farming work has much improved. Agricultural machinery significantly enhances our farming operations. Every spring, when the temperature is still low, especially in the rainy season, the farming machinery has helped improve our efficiency and shortened the time needed for spring ploughing and summer harvesting and re-planting. Thus, the farming jobs are done with machinery, freeing up lots of farming hands. Now, these free laborers can go out to work as migrant workers, making more income”.(Mr. Huang A., 42, the New Party Secretary)

Contrary to this optimistic view of modern farming with machinery, local ethnic Zhuang farmers depicted quite a different prospect. Another Mr. Huang (everyone in the village shared the surname of Huang), said,

“There are more mountains, few trees, very little arable land. Modern machinery does not help much. Mostly, we rely on manpower. Even though there are machines, such as tractors, we can only use them for transportation purposes. Every family would raise water buffalo, because they are useful and strong; very helpful with intensive labor”.(Mr. Huang B., 43, male, local farmer)

After highway construction, farming was significantly reduced. Many former agricultural farmers had to change to a different occupation, such as animal husbandry or forestry. Eventually, some people started planting trees in the mountains and selling wood or processing wood. A wood processing factory is expanding in scale. Raising animals is another new business. A new entrepreneur became quite successful in raising animals. He said:

“My father started to open wasteland 10 years ago. We traded our arable land with other families to raise animals. We raised sheep, cows, pigs, dogs, chicken, ducks, geese, and silkworm. We also have 300 Chinese acres of fruit trees, and 100 acres of sugar cane. I studied animal husbandry at the university… Whatever makes good money, we will do it”.(Mr. Yin, 35, Huang village accountant)

Exploring tourism is another venue that generates new income. A young female immigrant from Jiangxi Province, a Han person, has become an entrepreneur in developing local tourism. She said that her tourist company headquarters was in Guangxi Province, and her main goal right now was to attract investors.

“We are promoting a stock-share approach to invite local farmers and villagers to participate in local tourism. We hope we will gain support from the government, and our tourist company is responsible for raising the funds. Villagers could be share-holders. Once the principle is paid off, all villages could have a share of the local tourist industry”.(Ms. Lee, 30, Deputy Manager of Nongla Tourism Cooperation)

From the mainstream perspective, as presented by the Communist Party Secretary, highway construction has brought in new development and modernization with new machinery for agricultural labor. There is more machinery and more access to the outside world. Thus, there is a surplus of labor. Yet, from local ethnic villagers’ perspectives, machines were not useful because the arable land was small in scale; only water buffalos were practical for small areas of rice paddies. Villagers lost their self-sufficiency after highway construction. They had to rely on employment in cities as migrant laborers to make a living. The standard of living was not higher after the highway construction. Income insecurity increased and reliable livelihood reduced.

4.1. Changing Social Relations

Another major change after the highway construction is the changing social life and neighborhood in the community. With the highway cut across the village, the relocation of 201 families created the resettlement of a different neighborhood. Even though this resettlement is still among the people within the same village, the neighborhood has changed (see Figure 3). The Chinese government and highway companies designated the new neighborhood by a “fair” and random draw of dice coded with numbers. This “fair” and random draw of neighbors divided kinship and familiar social networks. Strangers became next-door neighbors. New buildings were constructed closely together in rows. Neighboring relations were becoming indifferent and quarrelsome. Some quarrels may have arisen due to property disputes; others due to estranged social relations.

Figure 3.

Geographic mapping of G75 Highway in the old and new village.

In the family of Jiang, for instance, the elderly father had two sons. Before Highway G75 was built, he had already divided his land between his two sons. Both were happy with their share. However, the highway construction cut across the land of the first son, so he received government compensation, but the second son did not because his land was not on the route of the highway. The second son felt it was unfair. He insisted that the land had to be re-divided by the father so he would receive equal monetary compensation from the government. The village cadre had to intervene in the matter several times before the family dispute was finally settled.

The resettlement by random assignment of housing had ruptured the original familial and neighboring relationships. Mr. Huang C., a 28-year-old farmer, described this change:

“Prior to the Highway construction, our houses were built as family compounds. Older and younger generational families in the extended family generally lived together in the same or neighboring extended family house-compound. When one family had a problem, the whole extended family would come up with a solution to solve the problem. Now, the housing assignment is based on a random selection. It has totally changed the traditional living arrangements. There are no more close connections with neighbors and extended families. House visits are unlikely to be with your current neighbors, but rather with relatives or former neighbors who are now living in a different location of the village.”

Social cohesion was also declining. Mutual respect was declining, and conflict resolution was no longer led by village elders or local cadres. Instead, court orders or lawsuits became more frequent. Mr. Lan, a 54-year-old agricultural mechanic, described this change as follows:

“Before, when there was a disagreement or dispute, the respected elders or older members in the extended family would come out to reconcile. Disputes were usually settled internally. Now, things have changed. Elders’ words are no longer heard or consulted. Usually, administrative officials would have to intervene at the initial stage. When the dispute escalates, usually the police or local court must intervene.”

Disintegration happens at various levels, among family members, between neighbors, and among villagers. Most disputes are related to monetary, land, or housing issues. The former relational ties, emotional connections, or blood ties have weakened or even appeared to matter less in the face of material interests and monetary benefits. Furthermore, what used to hold each other together was no longer there—their shared identity, culture, and religion.

4.2. The Loss of Religion and Culture

As discussed earlier, the village used to have four Sacred Rocks which held up the spirits of the village. During important holidays, villagers would go to temples or these Sacred Rock sites to worship ancestors or to pray for protection from the deities. In the process of the highway construction, one very Sacred Rock was eliminated by explosives. Villagers were displaced. Now, there are few occasions of togetherness.

Ms. Huang C., 53, recalled the days when villagers were together, sharing a sense of community by celebrating festivities together:

“In the days when I was young, every family was busy making Chinese cookies with gluten rice to sacrifice to the deities. The atmosphere of festivities was very strong. Everyone in the village used to gather to share meals together during festivals. In those days, money was not as important. Today, most young people have left the village to make money. Few are left behind to plough the land. There is no festivity to celebrate…”

Mr. Lan, a local village leader, shared a very similar sentiment with the following words:

“In the village, there used to be a local temple and Sacred Rock. The local temple was our collective worship site. In major worship days, the villagers would invite a Taoist master to select an auspicious day for the sacrificial ceremony. All villagers would prepare cooked chicken and cakes, burn paper money, wear ecclesiastical robes, and recite Scriptures. Before the Highway construction, we used to have a formal Sacrificial Ceremony once every three years…Now, villages may privately pray and perform a sacrificial ceremony at home.”

Another village elder echoed Mr. Lan’s sentiment. Mr. Huang D., at age 67, recounted the different attitudes of young people toward old customs:

“Nowadays, only older people like us still remember special holidays. Many traditional festivals have disappeared. Young people have gone to cities to work as migrant workers. The customs of ancestors are not something young people care about. They care more about fresh and new things in cities. We know the traditions and customs, but we no longer have much strength. We must let go…”

With few shared cultural activities, reduced social connection, and increased difficulty gathering for religious activities, villagers are experiencing a clear rupture of their culture because of the highway construction. One of the villagers murmured, looking aimlessly toward the future, that “Though the Sacred Rock is no longer there, our faith remains. In the future, we hope to find a different Sacred Rock to transcend our spirit so villagers will have a Sacred Object to Worship for sacrificial ceremonies.” Having four Sacred Rocks to hold up the four corners of the village seemed to have an important symbolic meaning for balance and peace to the villagers. Now that one Sacred Rock had been destroyed, the spirit of the people seems to be missing, displaced, and ruptured.

As shown, cultural practices, religious rituals, and social connections are all disrupted as a result of highway construction. Monetary compensation for villagers is a one lump sum, which may not even cover one year of expenditure and/or the reconstruction of half of a different house. Indeed, highway construction brought about changes in the diversification of employment and modernization of machinery and brought increasing levels of migration. How do the local villagers view these social changes? What do these social changes mean to them?

5. Discussion

The findings in this study echo many prior studies in terms of both the positive and negative impacts of modernization, in general, and highway construction, in particular, on the local people. Like the findings shown in other studies [6,7], occupational types in this Zhuang ethnic village have become diversified—from farmers to animal husbandry, forest and wood plant workers, and migrant factory or road construction workers. More people from the village have become urban by working as migrant workers (17% to 47%). Household income appears to be higher, since more people are working as migrant workers and earning a wage. Are people better off now compared to before the highway construction?

5.1. Modernity and Well-Being

From the perspectives of the Zhuang ethnic people, there is an increased sense of insecurity in livelihood. Although they did not earn much before, they did not need much cash. They grew their own rice, corn, and vegetables, and they raised their own chickens and pigs for their own food. Their livelihood was stable. Findings in this study lend support to Huang et al.’s study findings [6] that highway expansion created the disruption of livelihoods and that resettlement “reduced life satisfaction” of the local people. More machinery was available, yet land was appropriated for highway construction, so the originally small pieces of land which were plowed by water buffalos became further divided and minimized. What significance does modern machinery have when there is little land to plow anyway?!

5.2. The Legitimacy of Cultures

In the process of modernization, sometimes “people are in the way,” like in the case of the hydroelectric project in British Columbia, so they must be relocated. In the case of G75, Sacred Rock was in the way. It had to be eliminated by explosives. Even though the Sacred Rock was important for the religious rituals of the Zhuang people, it was not viewed as legitimate by the Han people because it was not written in the Han dynastic history of the past five hundred years. “Space is fundamental in any exercise of power” [11] (p. 252). Knowledge is power. The majority defines what makes legitimate cultural heritage. As Foucault puts it, local knowledges and their “subjugation” result in “an uneven geography.” [12] To remove anything in the way of highway construction, the majority and its government, in the push for highway expansion and modernization, ultimately monopolized power to define the legitimacy of space. The religious symbol of the Sacred Rock, important to the Zhuang ethnic people, was merely treated as “feudal” and “backward”, and to be rid of in the process of modernization.

Not all minority “supernatural” knowledges were dismissed by governments in the push for modernity. Examples in Canada and Iceland demonstrated the recognition and acceptance of local knowledge, be they “fairy tale elves” or hidden people. Highway constructions were halted; accidentally buried Sacred Rocks were uncovered. As shown, space, knowledge, and power are connected; they can be negotiated and shared. This process of negotiation and knowledge-sharing about spaces is an ongoing process, happening today in the U.S., as recently as the Supreme Court case in 2020 in Oklahoma [14]; in China; and in other regions of the world.

5.3. Religion and Social Cohesion

As Durkheim said, “Religion is something essentially social.” Religious rituals provide social connectivity, increase social cohesion, and, consequently, reduce social friction. In the Zhuang village, people used to celebrate festivities together and perform rituals together in front of the Sacred Rocks. When one of their Sacred Rocks is eliminated by explosives, what is wiped out is their collective memory, history, and social cohesion. As shown in this study, after relocation, neighbors, or even family members, are far more likely to quarrel for material or monetary matters. This decreased social cohesion is also documented in earlier studies of resettlement [21,22,23]. In his recent speech, President Xi Jingping encourages the preservation of ethnic cultures in the process of modernization and the alleviation of poverty. Yet, it is also important to recognize that the meanings and symbols of cultures must be defined by different ethnic people themselves; what is deemed important to one group may not mean anything to another. Yet, respecting the cultural symbols and rituals defined by ethnic people themselves is the first step to allow ethnic minorities to reclaim their own collective identity, memory, and history. The journey that Native American Indians traveled for the last 400 years for their freedom to self-determination and religious expression is still an ongoing battle today. Same is the battle of the Chinese ethnic minorities for their self-determination and freedom of religious expression.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J.Z. and H.-X.Z.; methodology, H.J.Z.; software, H.-X.Z.; validation, H.-X.Z.; formal analysis, H.J.Z. and H.-X.Z.; investigation, H.-X.Z.; resources, H.-X.Z.; data curation, H.-X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.J.Z. and H.-X.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.J.Z., H.-X.Z. and A.T.; funding acquisition, H.-X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This search, titled, “Social Conflict and Rural Organization and Management” is funded by Humanity and Social Science Research Foundation, Ministry of Education, China, in 2016. Funding # 16YJA840018.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, and the research protocol, titled, “Villages in migration and change—An analysis of migrants’ social adaptation after highway construction” was approved on 2014-9-30 by the Ethics Committee of Public Administration Institute, Hohai University, Nanjing, China.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants were fully informed about the purpose of the study and ensured that their anonymity was assured. Verbal informed consent was obtained by asking each participant the question: “Are you willing to participate in this study?” After the participant answered “Yes”, the researcher followed up by saying, “Do you understand that you are free to withdraw from this participation at any time?” The participant needed to understand and say “Yes” before the research started.

Data Availability Statement

Data is in Chinese and can be made available by directly contacting the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Moniz, M. Treading on Sacred Ground: Are Native American Sacred Cites Protected by the Freedom of Religion? 2017. Available online: https://www.freedomforuminstitute.org/first-amendment-center/topics/freedom-of-religion/free-exercise-clause-overview/treading-on-sacred-ground-are-native-american-sacred-sites-protected-by-the-freedom-of-religion/ (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Welch, A.B. Oral History of the Dakota Tribes 1800’s-1945—As Told to Colonel A.B. Welch, the First White man Adopted by the Sioux Nation. 2011/2012. Available online: https://www.welchdakotapapers.com/2011/12/sacred-stones-and-holy-places/#chapter-ii (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Smith, J.E. Eisenhower in War and Peace; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/aboutus/our-research-commitment (accessed on 11 August 2020).

- Loo, T. People in the way: Modernity, environment, and society on the Arrow Lakes. BC Stud. Vanc. Issue 2004, 142/143, 161–196. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Lin, W.; Li, S.; Ning, Y. Social impacts of dam-induced displacement and resettlement: A comparative case study in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Huang, S.-S. Relocation stress, coping, and sense of control among resettlers resulting from China’s Three Gorges Dam project. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 104, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G. The Economic Source of Ethnic Minority People’s Resentment—A Case Study of Liangshan Prefecture of Sichuan Province. Beijing Cult. Rev. 2014, 3, 38–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Hu, W. Roads, Settlements and Spatial Justice: An Anthropological Study of the Dali-Lijiang Highway and Its Node, Jiuhe. Open Times 2019, 6, 167–181. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mostowlansky, T. The road not taken enabling and limiting mobility in the Easter Pamirs. Int. Q. Asian Stud. 2014, 45, 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Space, Knowledge, and Power. In The Foucault Reader; Paul, R., Ed.; Pantheon: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 239–256. [Google Scholar]

- Elden, S.; Crampton, J. Space, Knowledge and Power: Foucault and Geography. Progressivegeography.com/Crampton-Elden-2007-Introduction. Available online: https://progressivegeographies.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/crampton-elden-2007-introduction.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Foucault, M. “Space Knowledge and Power” Interview by Paul Rabinow in Skyline (March 1982). Rizzoli Communications, Inc. Available online: https://foucault.info/documents/foucault.spaceKnowledgePower/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Tropiano, D. Professor Examines Court Ruling That Returned 3M Acres to Native American Nation: New Book Explains History Behind, Impact of ‘Bombshell’ Case. Arizona State University News, 24 January 2023. Available online: https://news.asu.edu/20230123-arizona-impact-professor-examines-court-ruling-returned-3-million-acres-native-american (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Geisler, C. Disowned by the ownership society: How native Americans lost their land. Rural. Sociol. 2014, 79, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipnis, A. Constructing commonality: Standardization and modernization in Chinese Nation-building. J. Asian Stud. 2012, 71, 731–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Qian, W.Y. Environmental migration and sustainable development in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River. Popul. Environ. 2006, 25, 613–636, Cited: p.631. [Google Scholar]

- Gongbo, F. Resettlement as development and progress? Eight years on: Review of emerging social and development impacts of an ‘Ecological resettlement’ project in Tibet Autonomous Region, China. Nomadic Peoples 2012, 16, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.-H. Why State-Sponsored Housing Schemes Fail--The Significance of Broadening Policy Studies in Ethnic Communities. J. Beifang Univ. Natl. 2014, 117, 40–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Decker, J.F. Gender and geographic impact of resettlement on Li Minority community, Hainan Island, China. Himal. Cent. Asian Stud. 2002, 6, 125–142, Cited, p. 128 and 136. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S.; Wang, M. Environmental resettlement and social dis/re-articulation in Inner Mongolia, China. Popul. Environ. 2006, 28, 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.H. Study on ecological poverty, ecological resettlement and social integration in Western China. Inn. Mong. Soc. Sci. 2004, 25, 128–133. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.Q.; Xie, J.; Li, Z.Y. On adaptation and amalgamation of Three Gorge external resettlement: An actual interview in Chongming County of Shanghai. Northwest Popul. 2005, 6, 16–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fei, X.T. Self Reflections on ‘Cultural Consciousness’. J. Theor. Ref. 2003, 9, 31–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, R.; Guang, K. Nationality issues in the perspective of Nation-building. Acad. Mon. 2015, 47, 169–176. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.F. A brief discussion on Han-descendant complex of Cen Yuying. Study Guangxi Ethnicity. 2008, 1, 85–101. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, X.L. On the development of Western China from an Anthropological Perspective. Ethno-Natl. Stud. 1997, 6, 29–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K. Integration among conflicts—On three cultural formations and their inter-relations. J. Guizhou Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 1998, 5, 19–25. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- In Iceland. Respect the Elves-or Else. The Guardian. 25 March 2015. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/mar/25/iceland-construction-respect-elves-or-else (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Eveleth, R. 1-15-2014. Napal Icelanders Protect a Road that Would Disturb Fairies. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/icelanders-protest-road-would-disturb-fairies-180949359/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Iceland Construction Workers Unearth Rock to Appease Angry Elves. Available online: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/iceland-construction-workers-unearth-rock-to-appease-angry-elves/HIRTRHVPCLNILJMBXCJQYR25PY/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Durkheim, E. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. In Social Theory—The multicultural and Classic Readings, 3rd ed.; Lemart, C., Ed.; Swain, J.W., Translator; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Westview. Cited p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. Ancestors Immigrant to City: The Cultural Logic of Demolition of Grave in A Village Nearby Wuhan City. China Agric. Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2015, 32, 61–69. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J. The Study on Hakka Community’ s Traditional Construction and Cultural Resistance—Taking the Affair of Protecting the Ancestral Temple as the Example. China Agric. Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2010, 27, 120–127. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wei, N. The exploratory explanation for the social functions of Zhuang Ethnic minority ‘She Gong’. J. Naning Polytech. 2015, 6, 86–88. [Google Scholar]

- Communist China Vs Falun Gong. Available online: https://www.worldatlas.com/politics/communist-china-vs-the-falun-gong.html (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Babbie, E. The Practice of Social Research, 11th ed.; Thomson Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 286–287. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).