Integrating Human Values Theory and Self-Determination Theory: Parental Influences on Preschoolers’ Sustained Sport Participation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Relationship Between Values and Behavior

2.1.1. Sport Values: Definition and Conceptualization

- Personal-oriented terminal values: Parents believe that sports help children gain personal growth and health, including enhancing physical fitness and boosting self-confidence.

- Social-oriented terminal values: Parents perceive sports as a means to foster social recognition, including building friendships, attaining competitive honors, and developing teamwork abilities.

- Competence instrumental values: Parents encourage children to cultivate effort, discipline, and a competitive spirit through sports to achieve higher athletic performance or personal accomplishments.

- Moral instrumental values: Parents view sports as an important vehicle for nurturing honesty, fair play, and respect for others.

2.1.2. Studies on the Relationship Between Values and Behavior

2.2. The Relationship Between Personal Values and Self-Determination Theory

2.2.1. Self-Determination Theory: Definition and Conceptualization

2.2.2. The Relationship Between Parental Sport Values and Self-Determination Theory

2.3. Definition and Conceptualization of Continued Participation Intention

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Objects and Data Collection

3.2. Analysis Methods and Data Analysis for Validity and Reliability

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Distribution of the Sample

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Overall Model Fit

4.4. Path Coefficient Significance Testing

5. Discussion

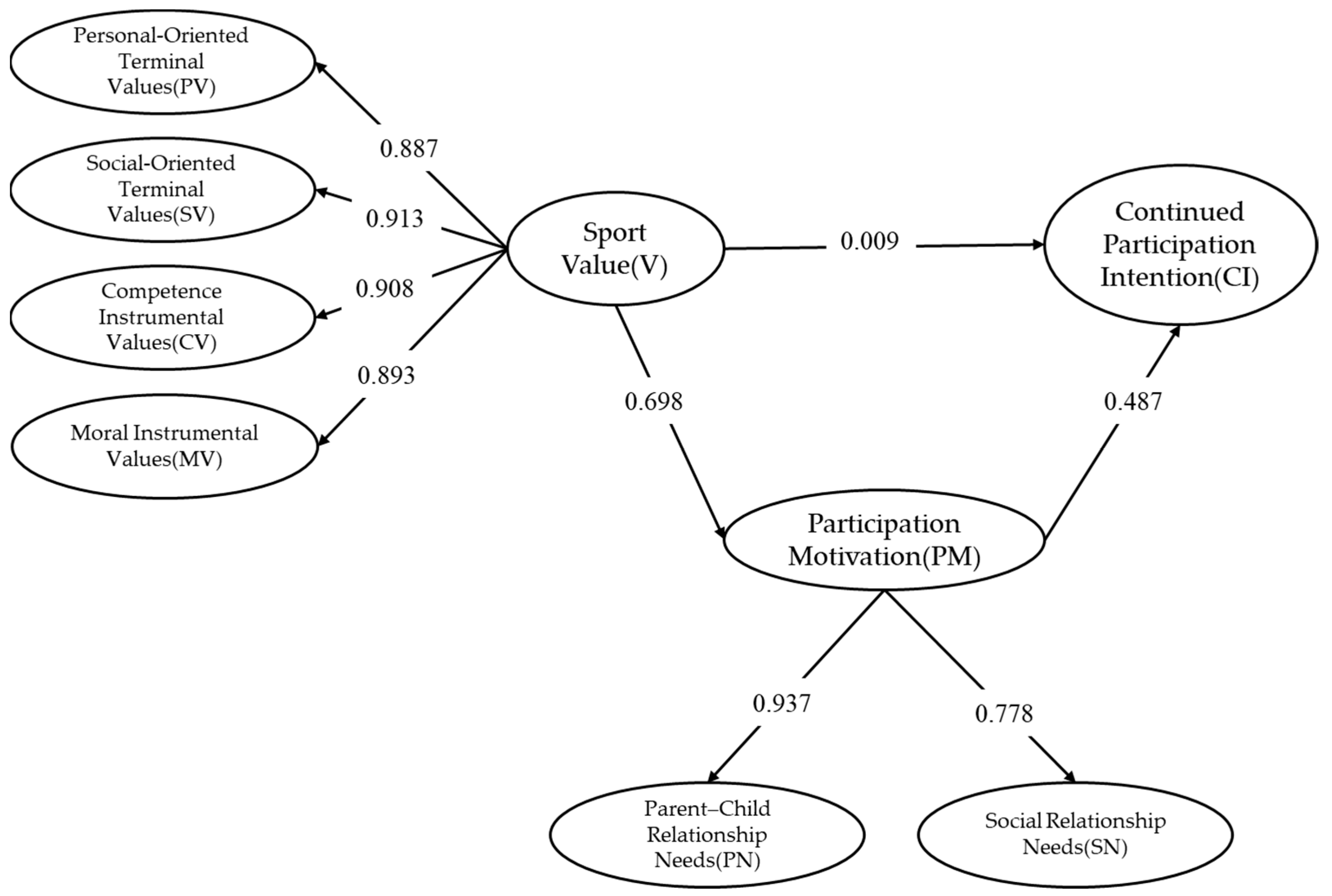

5.1. Results of Hypothesis Testing

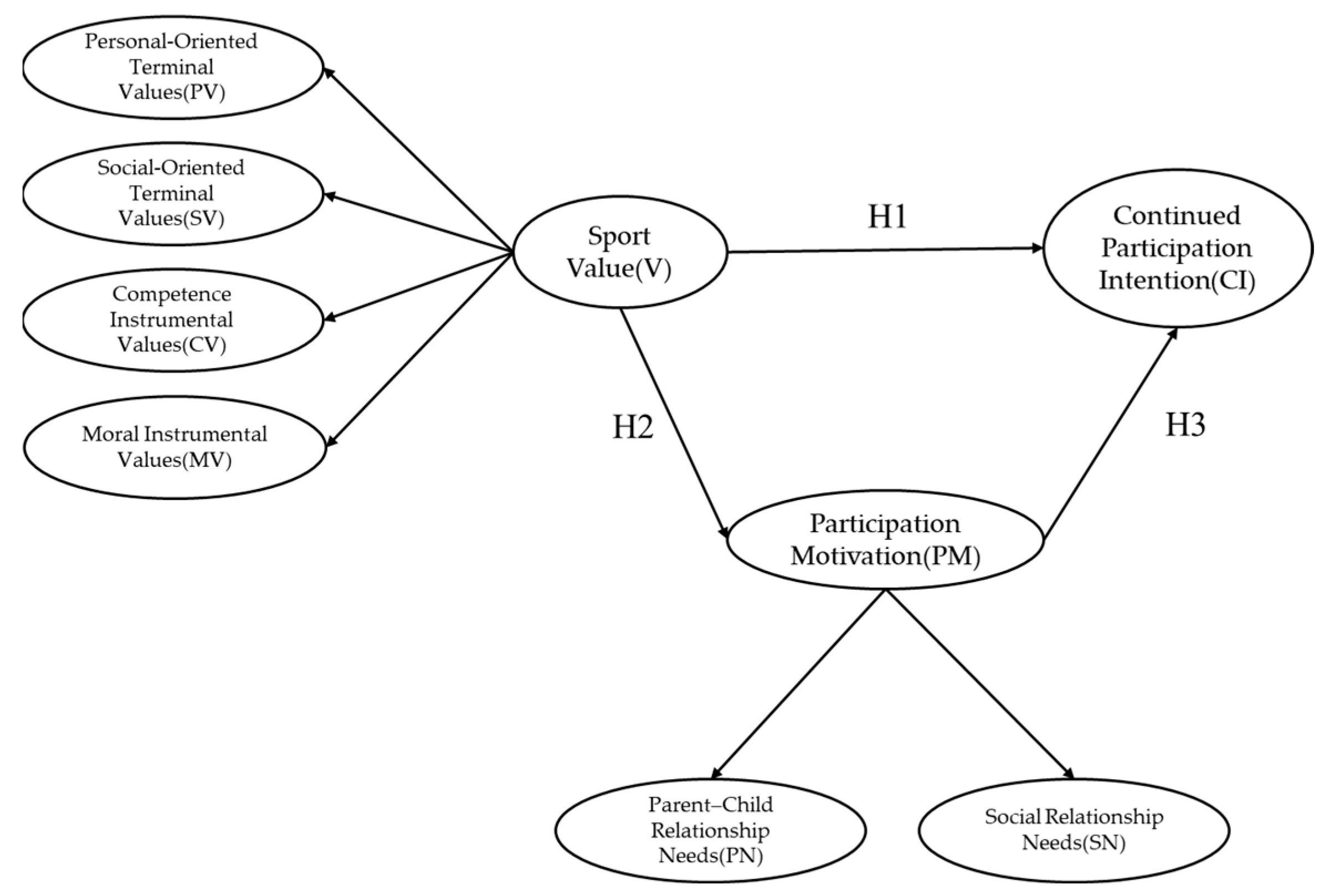

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Parents’ sport values have a significant positive effect on continued participation intention.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Parents’ sport values have a significant positive effect on participation motivation.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Participation motivation has a significant positive effect on continued participation intention.

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.3. Research Limitations

5.4. Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barrera, N.; Omolaoye, T.S.; Du Plessis, S.S. A contemporary view on global fertility, infertility, and assisted reproductive techniques. In Fertility, Pregnancy, and Wellness; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. Transition to below replacement fertility and policy response in Taiwan. Jpn. J. Popul. 2009, 7, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.-I.; Yang, S.-Y. From successful family planning to the lowest of low fertility levels: Taiwan’s dilemma. Asian Soc. Work Policy Rev. 2009, 3, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.C.; Chiang, Y.M.; Shih, Y.H.; Juan, C.Y.; Liu, Y.Y. The influence of the low birthrate on Taiwan’s preschool enrollment and strategies implemented to cope with this influence. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Lett. 2025, 13, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.P.; Wei, S. Child care friendly policies and integration of ECEC in Taiwan. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 2011, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues-Montanari, S. Clinical and psychological effects of excessive screen time on children. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2017, 53, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Eccles, J.S. Parental influences on youth involvement in sports. In Developmental Sport and Exercise Psychology: A Lifespan Perspective; Weiss, M.R., Ed.; Fitness Information Technology: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2004; pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Mercê, C.; Branco, M.; Catela, D.; Lopes, F.; Cordovil, R. Learning to cycle: From training wheels to balance bike. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blommenstein, B.; van der Kamp, J. Mastering balance: The use of balance bicycles promotes the development of independent cycling. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 40, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, A.; Mahoney, J.L. A longitudinal comparison of parent and child influence on sports participation. J. Youth Dev. 2013, 8, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Eccles, J.S. Family socialization, gender, and sport motivation and involvement. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2005, 27, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, G.D.O.; Santos, W.S.D.; Biermann, M.C.; Farias, M.G.; Plutarco, L.W. Influence of values and parenting styles perceived by children in the value transmission. Psicol. Teor. Pesqui. 2022, 38, e38318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-J.; Min, H. Influence of parents’ parenting values and beliefs on preschoolers’ problem behaviors. Korean J. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 15, 541–549. Available online: http://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/ArticleFullRecord.jsp?cn=HSGHBS_2006_v15n4_541 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Killoren, S.E.; Wheeler, L.A.; Updegraff, K.A.; McHale, S.M.; Umaña-Taylor, A.J. Associations among Mexican-origin youth’s sibling relationships, familism and positive values, and adjustment problems. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Teques, P.; Calmeiro, L.; Silva, C.; Borrego, C. The relationship between parents’ motivational profiles and their children’s motivation and enjoyment in sports. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 35, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidun, R.; Awang, M.M.; Ahmad, A.R.; Ahmad, A. Parent involvement in children learning to academic excellence. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Development and Multi-Ethnic Society, Medan, Indonesia, 10–11 October 2019; Redwhite Press: Medan, Indonesia, 2019; pp. 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick, W.S. Mothers’ motivation for involvement in their children’s schooling: Mechanisms and outcomes. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grolnick, W.S.; Ryan, R.M. Parent styles associated with children’s self-regulation and competence in school. J. Educ. Psychol. 1989, 81, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, F.; Ratelle, C.F.; Chanal, J. Optimal learning in optimal contexts: The role of self-determination in education. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Whitehead, J.; Ntoumanis, N. Development of the attitudes to moral decision-making in youth sport questionnaire (AMDYSQ). Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 369–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gano-Overway, L.A. Exploring the connections between caring and social behaviors in physical education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2013, 84, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haycock, D.; Smith, A. A family affair? Exploring the influence of childhood sport socialisation on young adults’ leisure-sport careers in north-west England. Leis. Stud. 2014, 33, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaf, D.; Wagnsson, S.; Skoog, T.; Glatz, T.; Özdemir, M. The interplay between parental behaviors and adolescents’ sports-related values in understanding adolescents’ dropout of organized sports activities. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2023, 68, 102448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danioni, F.; Barni, D.; Rosnati, R. Transmitting sport values: The importance of parental involvement in children’s sport activity. Eur. J. Psychol. 2017, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Chee, C.S.; Norjali Wazir, M.R.W.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; Wang, T. The role of parents in the motivation of young athletes: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1291711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Quested, E.; Reeve, J.; Cheon, S.H. Need supportive communication: Implications for motivation in sport, exercise, and physical activity. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 39, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joussemet, M.; Landry, R.; Koestner, R. A self-determination theory perspective on parenting. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolnick, W.S.; Pomerantz, E.M. Issues and challenges in studying parental control: Toward a new conceptualization. Child Dev. Perspect. 2009, 3, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, N. The personal meaning of participation: Enduring involvement. J. Leis. Res. 1989, 21, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koronios, K.; Kriemadis, T. An exploration of motives, constraints and future participation intention in sport and exercise events. Sport Bus. Manag. 2018, 8, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-J. Influence of intrinsic motivation and sport confidence for participation continuance intention on sports for all participant. Korean Soc. Sport Sci. 2022, 20, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.H. The relationships between participation motivation and continuous participation intention: Mediating effect of sports commitment among university futsal club participants. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C. Child–Parent Relationship Scale; University of Virginia: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard, A.B. Parent–Child Relationship Inventory (PCRI); Western Psychological Services: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona, C.E.; Russell, D.W. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. In Advances in Personal Relationships; Duck, S., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1987; Volume 1, pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason, I.G.; Levine, H.M.; Basham, R.B.; Sarason, B.R. Assessing social support: The Social Support Questionnaire. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.; Choi, C.; Park, S.U. Relationship between sports policy, policy satisfaction, and participation intention during COVID-19 in Korea. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231219537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ali, F. Partial least squares-structural equation modeling in hospitality and tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2018, 9, 238–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, A.H.; Rahman, I.A. Analysis of cost overrun factors for small scale construction projects in Malaysia using PLS-SEM method. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2013, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; D’Ambra, J.; Ray, P. An evaluation of PLS based complex models: The roles of power analysis, predictive relevance and GoF index. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, K.-R.; Paek, B.-J.; Yi, H.-T.; Huh, J.-H. Relationships between golf range users’ participation motivation, satisfaction, and exercise adherence intention. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2017, 11, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, Y.C. Motivations toward exercise participation: Active persons with multiple sclerosis have greater self-directed and self-capable motivations. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 102, 1232–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sejdija, S.; Maggio, A.B.R. Exploration of motivation to be physically active among overweight adolescents in Switzerland. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J. Development and initial validation of the group exercise motivation scale and associated factors in an Asian population. J. Sports Sci. 2025, 42, 2572–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dimension | Item | Original Sample | S.E. | T Statistics | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal- Oriented Terminal Values | PV1 | 0.750 | 0.033 | 22.779 | 0.876 | 0.587 |

| PV2 | 0.782 | 0.031 | 25.242 | |||

| PV3 | 0.794 | 0.026 | 30.402 | |||

| PV4 | 0.770 | 0.029 | 26.878 | |||

| PV5 | 0.733 | 0.041 | 17.960 | |||

| Social- Oriented Terminal Values | SV1 | 0.843 | 0.017 | 49.186 | 0.910 | 0.668 |

| SV2 | 0.826 | 0.022 | 38.235 | |||

| SV3 | 0.807 | 0.021 | 37.565 | |||

| SV4 | 0.844 | 0.017 | 49.432 | |||

| SV5 | 0.730 | 0.030 | 25.368 | |||

| Competence Instrumental Values | CV1 | 0.811 | 0.023 | 35.671 | 0.893 | 0.624 |

| CV2 | 0.781 | 0.029 | 25.928 | |||

| CV3 | 0.771 | 0.033 | 23.532 | |||

| CV4 | 0.804 | 0.024 | 32.925 | |||

| CV5 | 0.782 | 0.027 | 29.208 | |||

| Moral Instrumental Values | MV1 | 0.869 | 0.013 | 66.545 | 0.892 | 0.674 |

| MV2 | 0.833 | 0.018 | 46.853 | |||

| MV3 | 0.721 | 0.039 | 18.494 | |||

| MV4 | 0.852 | 0.017 | 49.255 | |||

| Parent– Child Relationship Needs | PN1 | 0.838 | 0.018 | 46.234 | 0.912 | 0.674 |

| PN2 | 0.820 | 0.025 | 33.269 | |||

| PN3 | 0.832 | 0.023 | 36.340 | |||

| PN4 | 0.815 | 0.020 | 41.313 | |||

| PN5 | 0.801 | 0.026 | 31.275 | |||

| Social Relationship Needs | SN1 | 0.887 | 0.010 | 85.156 | 0.883 | 0.716 |

| SN2 | 0.898 | 0.012 | 66.843 | |||

| SN3 | 0.745 | 0.037 | 20.286 | |||

| Continued Participation Intention | CI1 | 0.828 | 0.020 | 42.348 | 0.903 | 0.700 |

| CI2 | 0.734 | 0.031 | 23.964 | |||

| CI3 | 0.891 | 0.015 | 61.331 | |||

| CI4 | 0.883 | 0.013 | 68.560 |

| 1.V | 2.PM | 3.CI | |

| 1.V | 0.718 | ||

| 2.PM | 0.698 | 0.728 | |

| 3.CI | 0.350 | 0.494 | 0.836 |

| Dimension | AVE | Composite Reliability | R2 | Cronbach’s Alpha | GOF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents’ Sport Values | 0.516 | 0.953 | - | 0.947 | 0.466 |

| Participation Motivation | 0.531 | 0.899 | 0.487 | 0.869 | |

| Continued Participation Intention | 0.700 | 0.903 | 0.241 | 0.855 |

| Hypothesis | Effects | t | p | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Sport Value → Continued Participation Intention | 0.153 | 0.879 | Non-significant |

| H2 | Sport Value → Participation Motivation | 19.478 | 0.000 | Significant |

| H3 | Participation Motivation → Continued Participation Intention | 8.132 | 0.000 | Significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, C.-W.; Huang, Y.-J.; Chen, K.-H.; Chen, M.-K. Integrating Human Values Theory and Self-Determination Theory: Parental Influences on Preschoolers’ Sustained Sport Participation. Societies 2025, 15, 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070199

Lin C-W, Huang Y-J, Chen K-H, Chen M-K. Integrating Human Values Theory and Self-Determination Theory: Parental Influences on Preschoolers’ Sustained Sport Participation. Societies. 2025; 15(7):199. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070199

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Chih-Wei, You-Jie Huang, Kai-Hsiu Chen, and Ming-Kuo Chen. 2025. "Integrating Human Values Theory and Self-Determination Theory: Parental Influences on Preschoolers’ Sustained Sport Participation" Societies 15, no. 7: 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070199

APA StyleLin, C.-W., Huang, Y.-J., Chen, K.-H., & Chen, M.-K. (2025). Integrating Human Values Theory and Self-Determination Theory: Parental Influences on Preschoolers’ Sustained Sport Participation. Societies, 15(7), 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070199