A Review About the Effects of Digital Competences on Professional Recognition; The Mediating Role of Social Media and Structural Social Capital

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background

2.1. From Digital Competences to Digital Capital

2.2. Social Capital and Professional Recognition

2.3. Digital Competences for Improving Social Capital Through Professional Recognition

3. Research Questions

- RQ1: What are the most commonly mobilized theoretical frameworks for analyzing how digital competences are transformed into social capital and professional recognition?

- RQ2: In what ways do digital competences shape processes of social and professional recognition?

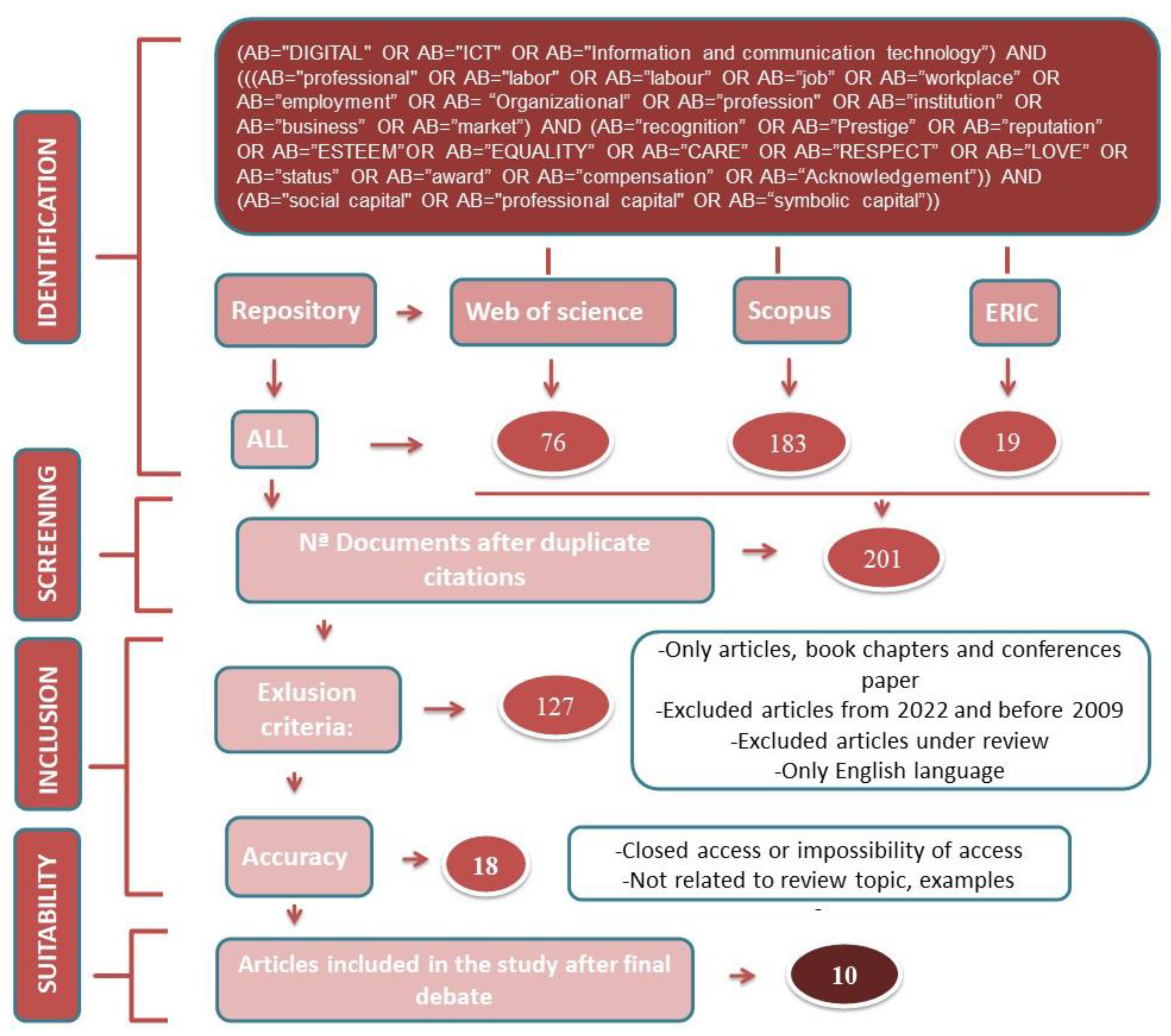

4. Methodology

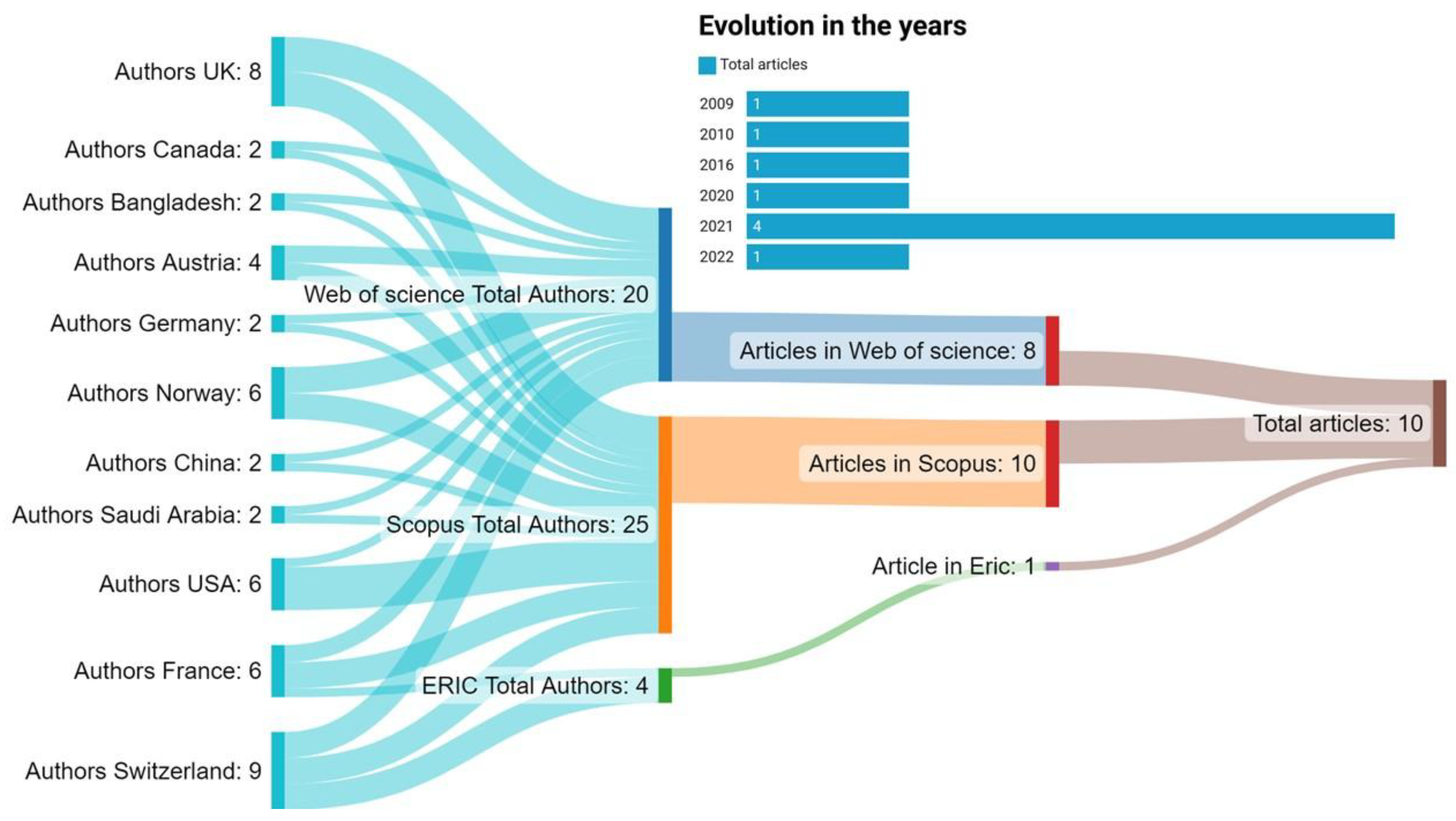

4.1. Identification and Screening

- Web of Science (WOS): Recognized as one of the most authoritative and comprehensive platforms for scholarly literature, Web of Science indexes a wide array of peer-reviewed journals through its Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Science Citation Index (SCI).

- Scopus: Scopus is an internationally renowned bibliographic database, comparable in scope and rigor to the SCI.

- ERIC (Education Resources Information Center): ERIC stands as a leading specialized database in the field of education. It is distinguished by its broad coverage of scholarly and professional resources, including peer-reviewed journal articles, research reports, conference proceedings, policy briefs, and doctoral dissertations.

4.2. Inclusion and Eligibility Criteria

4.3. Coding and Grouping

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. RQ1: What Are the Most Commonly Mobilized Theoretical Frameworks for Analyzing How Digital Competences Are Transformed into Social Capital and Professional Recognition?

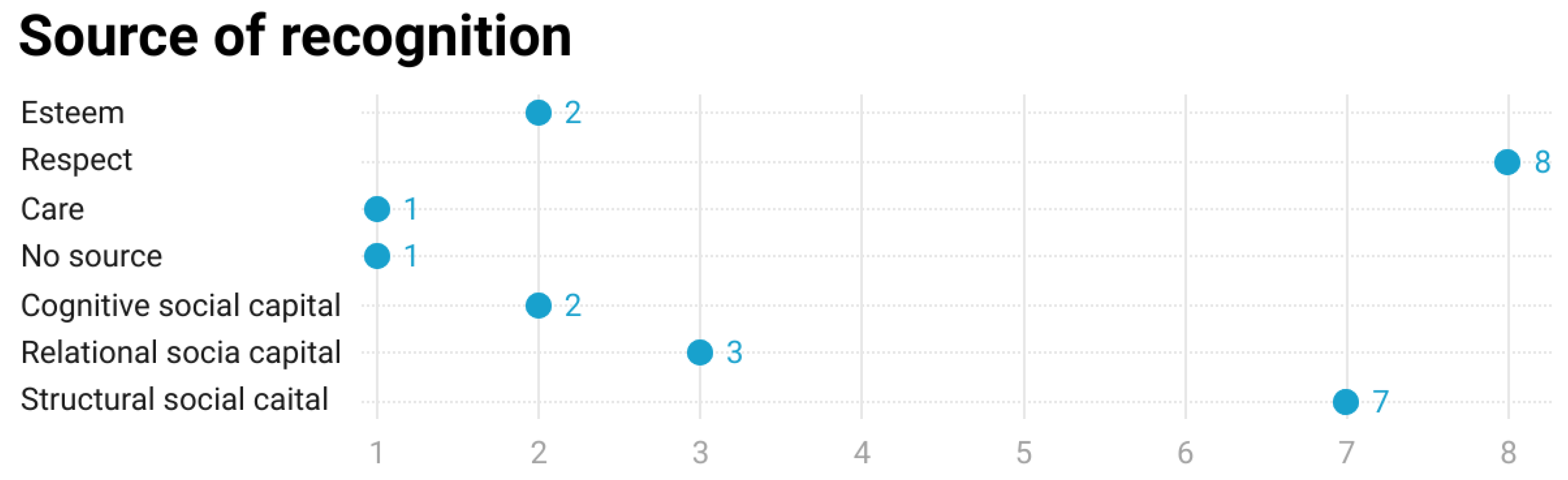

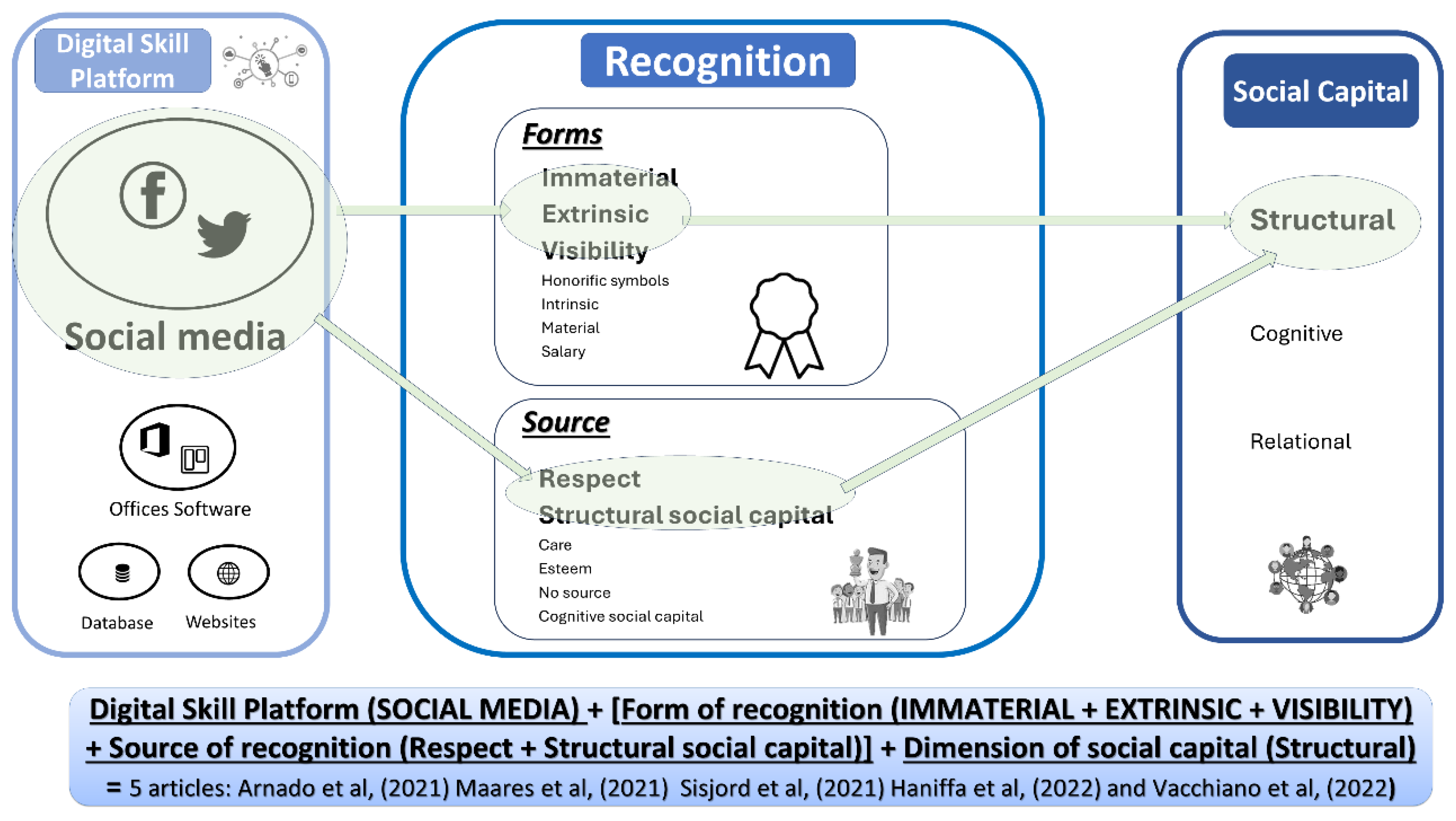

5.2. RQ2: In What Ways Do Digital Competences Shape Processes of Social and Professional Recognition?

6. Conclusions

6.1. Principal Results to Our Two Research Questions

6.2. A Contemporary Reappraisal of Recognition in the Era of Digital Social Networks: Intersections with Structural Social Capital

6.3. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Coding Scheme Used

| Research and year (1.R) | Ganley and Lampe (2009), Gayen et al. (2010)… (For more details about the coding of the rest of the journals, click on the link in the note of this table titled general matrix) |

| BIBLIOMETRIC DATA | |

| Repository (2.R) | WOS (1) |

| SCOPUS (2) | |

| ERIC (3) | |

| Document types (2.DT) | Articles (1) |

| Conference paper (2) | |

| Book chapter (3) | |

| Journal (2.J) | Decision Support Systems, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy… (For more details about the coding of the rest of the journals, click on the link in the note of this table titled general matrix) |

| Country of authorship (2.AN) | USA (1) |

| Canada (2) | |

| UK (3) | |

| Bangladesh (4) | |

| France (5) | |

| Austria (6) | |

| Germany (7) | |

| Norway (8) | |

| China (9) | |

| Saudi Arabia (10) | |

| Switzerland (11) | |

| OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY (3.0) | Deep qualitative response, click on the link in the note of this table titled deepening table (IT) |

| SAMPLE AND STUDY FOCUS AREA | |

| Sample (4.S) | Deep qualitative response, click on the link in the note of this table titled deepening table (IT) |

| Focus group according to Von Schrader, Shaw, and Colella (2024) (4.FG) | Institution (1) |

| Company (2) | |

| Supervisor (3) | |

| Employee (4) | |

| People looking for work (5) | |

| General, several groups at the same time (6) | |

| Type of work area (4.TW) | Education (1) |

| Healthcare (2) | |

| Technology (3) | |

| Business (4) | |

| General, several type of work area at the same time (5) | |

| Famous artist (6) | |

| Journalism (7) | |

| Sports (8) | |

| Scientific (9) | |

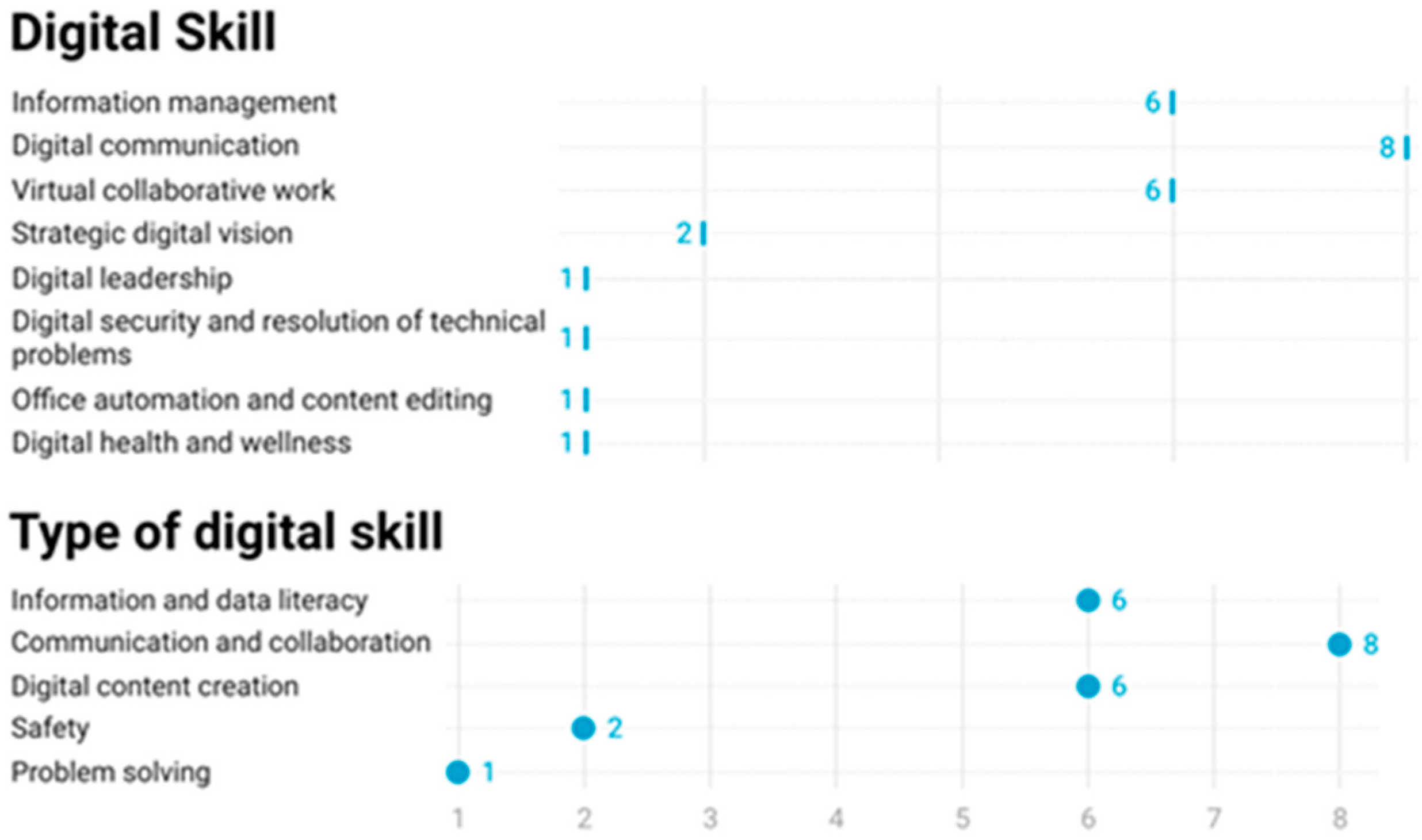

| TYPES OF DIGITAL SKILLS AND INVOLVED PLATFORMS | |

| Digital skill according to World Bank (2019), Banga and te Velde (2019) and Segrera-Aarellana et al. (2020). (5.DS) | Information management (1) |

| Digital communication (2) | |

| Virtual collaborative work (3) | |

| Strategic digital vision (4) | |

| Digital leadership (5) | |

| Digital security and technical resolution (6) | |

| Office automation and content editing (7) | |

| Digital health and wellness (8) | |

| Unspecified (9) | |

| All of them (10) | |

| Type of digital skill according to Vuorikari et al. (2022) (5.TD) | Information and data literacy (1) |

| Communication and collaboration (2) | |

| Digital content creation (3) | |

| Safety (4) | |

| Problem solving (5) | |

| Unspecified (6) | |

| All of them (7) | |

| Tool or platform for the development of digital skills (5.TP) | Twitter (1) |

| Blogs (2) | |

| Trello (3) | |

| SlashDot (4) | |

| UK Data Service (5) | |

| IRMA (6) | |

| Unspecified (Media platforms) (7) | |

| Social media (8) | |

| News websites (9) | |

| e-commerce (10) | |

| Offices Software (11) | |

| Leisure (12) | |

| frequency (13) | |

| Google Meet (14) | |

| Zoom (15) | |

| Facebook (16) | |

| Social network in general (17) | |

| Google scholar (18) | |

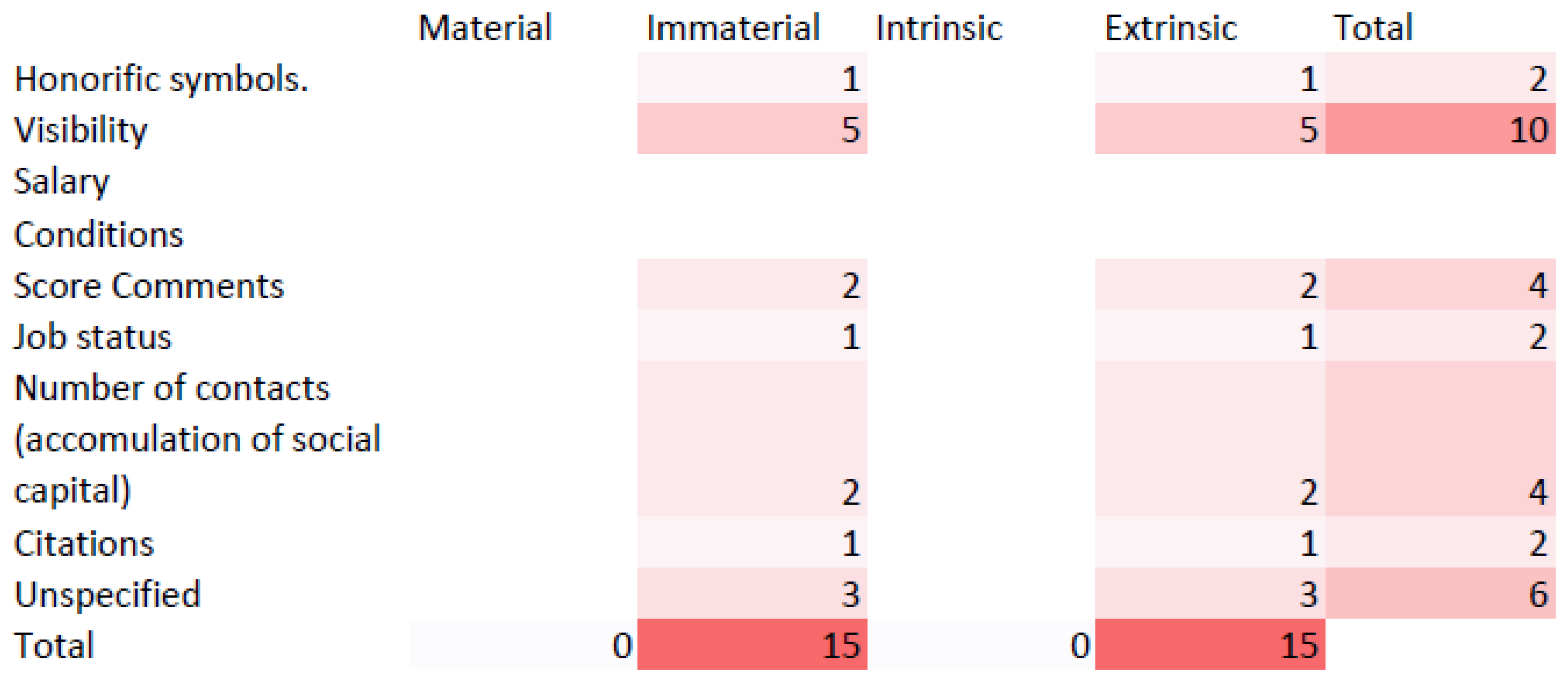

| PROFESSIONAL RECOGNITION | |

| Theorical framework professional recognition (6.TF) | Deep qualitative response, click on the link in the note of this table titled deepening table (IT) |

| Forms of recognition according to Brillet et al. (2013) and Onge et al. (2011) (6.FR) | Material (1) |

| Immaterial (2) | |

| Intrinsic (3) | |

| Extrinsic (4) | |

| Honorific symbols (5) | |

| Visibility (6) | |

| Salary (7) | |

| Conditions (8) | |

| Score Comments (9) | |

| Job status (10) | |

| Number of contacts (accumulation of social capital) (11) | |

| Citations (12) | |

| Source of recognition according to Honeth (1990) | Esteem (1) |

| Respect (2) | |

| Care (3) | |

| No source (4) | |

| Cognitive social capital (5) | |

| Social Capital Relations (6) | |

| Structural social capital (7) | |

| Tool to collect the data (6.TD) | Deep qualitative response, click on the link in the note of this table titled deepening table (IT) |

| Data collection method (5.DM) | Deep qualitative response, click on the link in the note of this table titled deepening table (IT) |

| SOCIAL CAPITAL | |

| Theoretical framework social capital (7.TF) | Deep qualitative response, click on the link in the note of this table titled deepening table (IT) |

| Dimensions of social capital (7.DS) | Structural (1) |

| Cognitive (2) | |

| Relational (3) | |

| Tool to collect the data (7.TD) | Deep qualitative response, click on the link in the note of this table titled deepening table (IT) |

| Data collection method (7.DM) | Deep qualitative response, click on the link in the note of this table titled deepening table (IT) |

| Finds (8.F) | Deep qualitative response, click on the link in the note of this table titled deepening table (IT) |

| Current and future trends (9.FT) | Deep qualitative response, click on the link in the note of this table titled deepening table (IT) |

| OTHERS | |

| Try to increase economic capital according to Bourdieu (OT.1) | Yes (1) |

| No (2) | |

| Informal situations are used (OT.2) | Yes (1) |

| No (2) | |

| Notes: Full analysis at the following links (open access). General matrix: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1V3B0Te8jI8U3h-piIXgY6jCSkpXfOLJW/view?usp=sharing (20 March 2025) https://drive.google.com/file/d/1XOvAlPK6cHMiEGxbfl3rq1aZ7IX6wEVX/view?usp=sharing (20 March 2025). | |

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Topic and focus of study | Digital competences contribute to social capital through professional recognition | Not provide substantial evidence or primarily focus on other aspects of digital competences, such as personal well-being or recreational technology use. |

| Language | English or Spanish | - |

| Publication period | January 2009–December 2022 | Articles excluded 2022 onward and those before 20009 |

| Type of publication | Articles, book chapters, and conference communications | Books, posters, workshop documents, editorials, and reports. |

| Publication status | Peer-reviewed articles | Non-peer-reviewed and in-press articles |

| Other | Accessible | Inaccessible, and literature reviews |

References

- Carretero, S.; Vuorikari, R.; Punie, Y. DigComp 2.1. The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens. With Eight Proficiency Levels and Examples of Use; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmans, M.; Lub, X.; Orlowski, M.; Nguyen, T. Developing the digital transformation skills framework: A systematic literature review approach. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304127. [Google Scholar]

- Peiró, J.M.; Martínez-Tur, V. ‘Digitalized’ Competences. A Crucial Challenge beyond Digital Skills. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2022, 38, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laar, E.A.; Van Deursen, A.J.; Van Dijk, M.G.; De Haan, J. The relation between 21st-Century skills and digital skills: A systematic literature review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Report: The Changing Nature of Work. 2019. Available online: https://www.bancomundial.org/es/publication/wdr2019 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- UNESCO. A Global Framework of Reference on Digital Literacy Skills for Indicator. 2018. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/en/news/unesco-launches-global-framework-digital-literacy-skills (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Ruziev, M.; Yu, U. The impact of digitalization on the labor market and the development of professional competences. Univ. Knowl. Soc. J. 2024, 3, 336–337. Available online: https://s-lib.com/en/issues/uik_2024_03_a8/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Helsper, E.J.; Eynon, R. Distinct skill pathways to digital engagement. Eur. J. Commun. 2013, 28, 696–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. Handb. Theory Res. Sociol. Educ. 1986, 241, 258. [Google Scholar]

- Calderon Gomez, D. The third digital divide and Bourdieu: Bidirectional conversion of economic, cultural, and social capital to (and from) digital capital among young people in Madrid. New Media Soc. 2021, 23, 2534–2553. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H.; Purushotma, R.; Weigel, M.; Clinton, K.; Robinson, A.J. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van Deursen, A.J.; Helsper, E.J.; Eynon, R. Measuring Digital Skills. From Digital Skills to Tangible Outcomes Project Report; University of Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, D.J. Perception and the Fall from Eden; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, N. La Civilisation des Moeurs; Calmann-Lévy: Paris, France, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, L.A. Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-Machine Communication; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Keen, C.; France, A. Capital gains in a digital society: Exploring how familial habitus shapes digital dispositions and outcomes in three families from Aotearoa New Zealand. New Media Soc. 2022, 14, 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaç, A.; Emine, O. How digital reading differs from traditional reading: An action research. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2019, 15, 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ragnedda, M. Conceptualizing digital capital. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 2366–2375. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiu, M.L.; Ragnedda, M. Digital capital and online activities: An empirical analysis of the second level of digital divide. First Monday 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lybeck, R.; Koiranen, I.; Koivula, A. From digital divide to digital capital: The role of education and digital skills in social media participation. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 2024, 23, 1657–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Costa, C.S. The Role of AI in the Digital Skill Development of Employees in SMEs. Master’s Thesis, University of Vaasa, Vaasa, Finland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Van Deursen, A.J.A.M.; Helsper, E.J. The third-level digital divide: Who benefits most from being online? Commun. Inf. Technol. Annu. 2015, 10, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangrazio, L. Reconceptualising critical digital literacy. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2016, 37, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A. Digital Competence in Practice: An Analysis of Frameworks; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, A. Cultural Capital, Cultural Knowledge and Ability. Sociol. Res. Online 2017, 12, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthauer, L.; Kauffeld, S. The role of social networks for careers. Gr. Interakt. Organ. Z. Angew. Organ. 2018, 49, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn, A.; Beetham, H.; McGill, L. Digital Literacy as a Catalyst for Change: A Report on the Digital Literacies in Higher Education; JISC: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, C.; Hubert, K.; Paul, L. Technology and Social Interaction: The Emergence of ‘Workplace Studies; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Keele University: Newcastle, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Douglas, G.; Altman, J.T.; Mulrow, C.; Peter, C.; Gøtzsche, J.; Ioannidis, P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.A.; Liberati, J.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, A.D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, E.M.; Winter, D.; Escalona, M.J.; Thomaschewski, J. Key Challenges in Agile Requirements Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Banga, K.; Velde, D.W. Preparing Developing Countries for the Future of Work: Understanding Skills-Ecosystem in a Digital Era. 2019. Available online: https://pathwayscommission.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-11/preparing_developing_countries.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Brillet, F.; Coutelle, P.; Hulin, A. Proposition d’une mesure de la reconnaissance: Une approche par la justice perçue. Rev. De Gest. Des Ressour. Hum. 2013, 89, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Honneth, A. Teoría Crítica; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Nahapiet, J.; Sumantra, G. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schrader, S.; Shaw, L.; Colella, A. Perceptions of federal workplace attributes: Interactions among disability, sex, and military experience. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2024, 34, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vlies, R. OECD Digital strategies in education across OECD countries: Exploring education policies on digital technologies. OECD Educ. Work. Pap. 2020, 226, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, R.S. Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Le capital stock: Notes provisoires. Actes De La Rech. En Sci. Soc. 1980, 31, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democr. 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- St-Onge, M.P.; Roberts, L.A.; Chen, J.; Kelleman, M.; O’Keeffe, M.; RoyChoudhury, A.; Jones, P.J. Short sleep duration increases energy intakes but does not change energy expenditure in normal-weight individuals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renger, D.; Renger, S.; Miché, M.; Simon, B. A social recognition approach to autonomy: The role of equality-based respect. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claridge, T. Dimensions of Social Capital. 2018. Available online: https://www.socialcapitalresearch.com/category/dimensions/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Spence, M. Job Market Signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen, A. Interpersonal recognition: A response to value or a precondition of personhood? Inquiry 2002, 45, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, P.M. Recognizing the limitations of the political theory of recognition: Axel Honneth, Nancy Fraser and social work. Br. J. Soc. Work 2010, 40, 1517–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N.; Mahadi, N. Mutual Recognition Respect Between Leaders and Followers: Its Relationship to Follower Job Performance and Well-Being. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricoeur, P. Becoming capable, being recognized. Esprit 2005, 7, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Maak, T. Responsible Leadership, Stakeholder Engagement, and the Emergence of Social Capital. J. Bus. Ethics. 2007, 74, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, R.; Hudaib, M.; Nawaz, T. El valor del capital social para el éxito de las IPO de SPAC. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2022, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisjord, M.K.; Fasting, K.; Sand, T.S. Gendered pathways to elite coaching reflecting the accumulation of capitals. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021, 26, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacchiano, M.; Hollstein, B.; Settersten, R.A., Jr.; Spini, D. Networked lives: Probing the influence of social networks on the life course. Adv. Life Course Res. 2024, 59, 100590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arando, S.; Gago, M.; Freundlich, F.; Ugarte, L. Capital social y cooperativismo. Projectics/Proyéctica/Projectique 2012, 1112, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maares, P.; Banjac, S.; Hanusch, F. The labour of visual authenticity on social media: Exploring producers’ and audiences’ perceptions on Instagram. Poet. J. Empir. Res. Cult. Media Arts 2021, 84, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, E.C.; Robert, J.; Sparrow, J.; Wee, J.; Dudas, P.; Slattery, M.J. A digital fluency framework to support 21st-century skills. Change Mag. High. Learn. 2021, 53, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Topic and focus of study | Digital skills contribute to social capital through professional recognition | Not provide substantial evidence or primarily focus on other aspects of digital skills, such as personal well-being or recreational technology use. |

| Language | English or Spanish | - |

| Publication period | January 2009–December 2022 | Articles excluded 2022 onward and those before 20009 |

| Type of publication | Articles, book chapters, and conference communicat | Books, posters, workshop documents, editorials, and reports. |

| Publication status | Peer-reviewed articles | Non-peer-reviewed and in-press articles |

| Other | Accessible | Inaccessible, and literature reviews |

| Item | Assessment Criteria | Score | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| QA1 | Were the objectives of the research clearly stated? | −1 | The objectives were not described |

| 0 | The objectives were partially but unclearly described | ||

| 1 | Yes, the objectives were well described and clear | ||

| QA2 | Does the article include a detailed description of the proposed solution or approach? | −1 | No, details were missing |

| 0 | Partially, if you wish to use the approach or solution, you must read the references | ||

| 1 | Yes, the approach can be used based on the presented details | ||

| QA3 | Is the proposed solution or approach valid? | −1 | No |

| 0 | It was partially validated in a laboratory, or only portions of the proposal were validated | ||

| 1 | Yes, by a case study | ||

| QA4 | Does the article present an opinion or viewpoint? | −1 | Yes |

| 0 | Partially because the corresponding work was explained, and the work was set into a specific context | ||

| 1 | No, the paper was based on research | ||

| QA5 | Has the study been cited in other scientific publications? | −1 | No, no one cited the study |

| 0 | Partially. Between one and five scientific papers cited the study | ||

| 1 | Yes, more than five scientific papers cited the study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De la Hoz-Ruiz, J.; Chaker, R.; Fernández-Terol, L.; Olmo-Extremera, M. A Review About the Effects of Digital Competences on Professional Recognition; The Mediating Role of Social Media and Structural Social Capital. Societies 2025, 15, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070194

De la Hoz-Ruiz J, Chaker R, Fernández-Terol L, Olmo-Extremera M. A Review About the Effects of Digital Competences on Professional Recognition; The Mediating Role of Social Media and Structural Social Capital. Societies. 2025; 15(7):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070194

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe la Hoz-Ruiz, Javier, Rawad Chaker, Lucía Fernández-Terol, and Marta Olmo-Extremera. 2025. "A Review About the Effects of Digital Competences on Professional Recognition; The Mediating Role of Social Media and Structural Social Capital" Societies 15, no. 7: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070194

APA StyleDe la Hoz-Ruiz, J., Chaker, R., Fernández-Terol, L., & Olmo-Extremera, M. (2025). A Review About the Effects of Digital Competences on Professional Recognition; The Mediating Role of Social Media and Structural Social Capital. Societies, 15(7), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070194