Sensory Methodologies and Methods: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

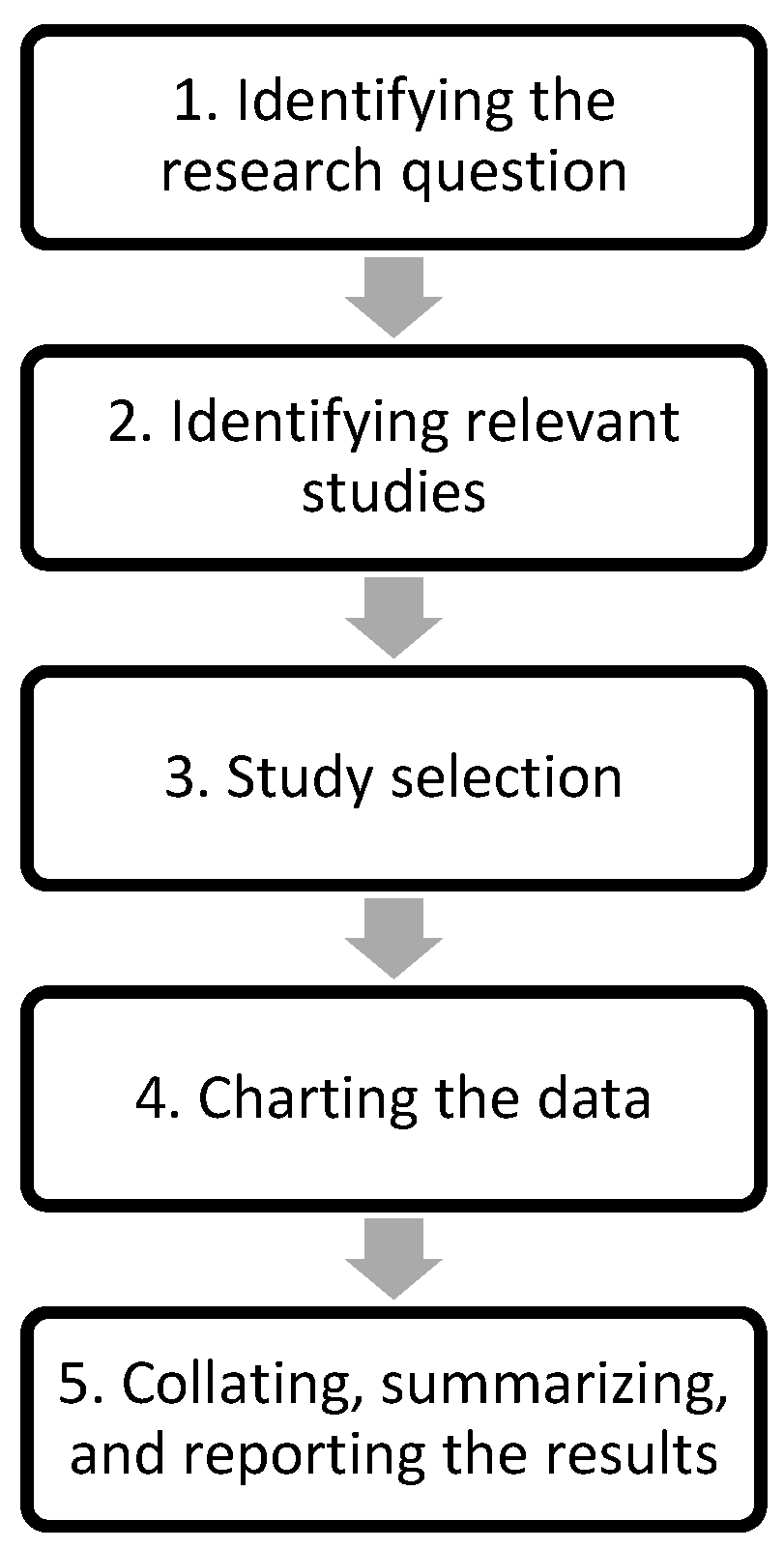

2. Methods

2.1. Identifying the Research Questions

- 1.

- What is the extent and nature of research activities that use multisensory methodologies?

- 2.

- What is the extent and nature of research activities that use multisensory methods?

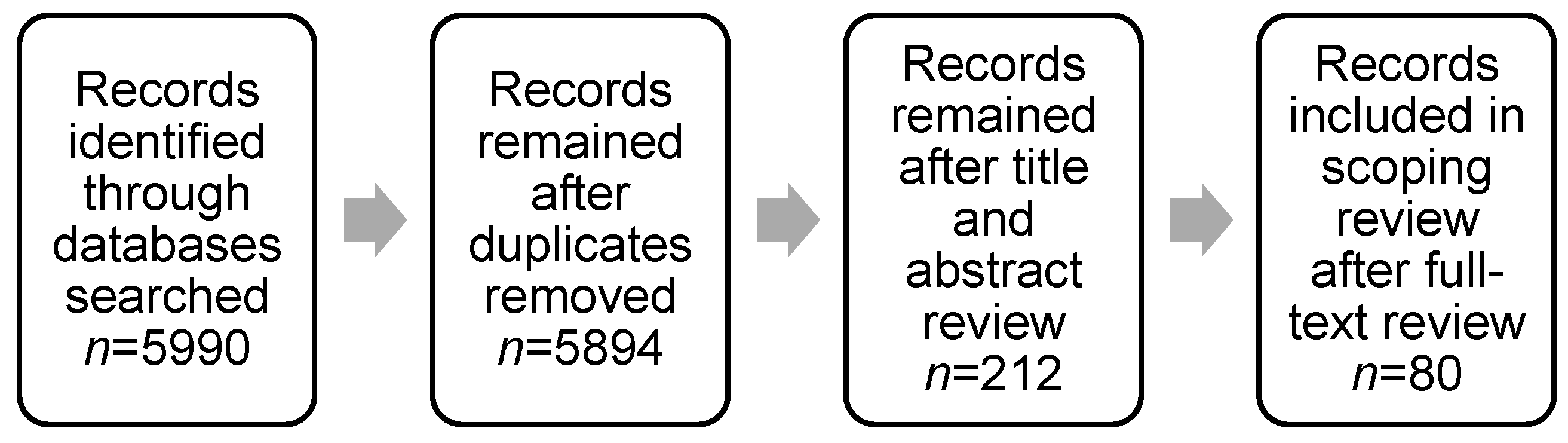

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Charting the Data

2.5. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting Results

3. Results

3.1. Multisensory Methodologies

- 1.

- Ethnographic-based methodologies:(1a) General refers to studies that solely noted “ethnography” [19,27,35,48,56,63,64,66,67,69,71,73,81,87,89,92,93].(1c) Blended sensory ethnography: reflexive sensory ethnography and video ethnography [46]; sensorial autoethnography [72]; sensory and performance-focused ethnography [91]; multispecies ethnography and sensory anthropology [40]; sensory ethnography and video ethnography [50]; and visual and sensory ethnography [28].(1f) Other: ethnomethodologic interaction analysis [14]; rhizomic ethnography [60]; ethnographic case study [61]; autobiographical performance ethnography ** [62]; ethnography and performative discourse analysis [82]; collaborative and multimedia ethnography [90]; passive ethnography [68]; ethnography and transdisciplinary methodology [44]; and ethnomethodology and video ethnography [26].

- 2.

- Phenomenology-based methodologies:(2a) Phenomenology [15].(2b) phenomenology and sensory [83].

- 3.

- Participatory-based methodologies:(3b) Sensory and visual participatory [41].(3c) Arts-based research: participatory action research and arts-based research [42].(3d) Ethnography and participatory: ethno-mimesis and participatory action research [43].

- 4.

- Other methodologies:(4b) Multimodal clinical study [47].(4c) Digital storytelling [17].(4d) Narrative inquiry [24].(4e) Case study [85].(4f) Portraiture methodology [65].(4g) Technoecology [55].

- 5.

3.2. Multisensory Methods

- 1.

- Kinesthetic:(1a) Body movements [30,57]: bodily engagement [46,68,70,81,82,85,87,91]; sensory motor engagement [15]; and engagement with vibrations through mediating objects [47].(1c) Dharma vajras mediated sensory practices, body alignment, and perceptual attunement [67].(1d) Itinerant soliloquies [41].(1f) Thermoception [16].

- 2.

- Mapping:(2a) Body mapping [25].(2d) Participatory mapping [90].

- 3.

- Sound:(3a) Audio-visual material, speculative hermeneutics, and music analysis [33].(3b) Sonic technoecology [55].(3e) Sound diaries [45].(3g) Performance of songs [66].

- 4.

- Smell:(4a) Blind smell association experiment [92].(4c) Smellkit [79].(4d) Smellscapes [38].

- 5.

- Taste:(5a) Cooking and eating [76].(5c) Material esthetic of food [91].(5d) Taste elicitation interviews [27].

- 6.

- Touch:

- 7.

- Visual:(7a) Digital storytelling [17].(7b) Graphic elicitation interviews [41].(7c) Photographs [28,32,39,42,43,49,59,64,71,74,86,90]; photo journals [61]; photo-elicitation interviews [32,53,89]; and pictures [84].

- 8.

- Other:(8a) Active participation in events is the act of being attuned to the senses in an embodied understanding of the topic in active participation of events and sensory engagement [46,70,78,81,82,85,87,91].(8d) Descriptive sensory evaluation [80].(8e) Memory [78].(8f) Nonvisual apprehensions, alternative modes of visual perception, and space [29].(8g) Puppets [24].(8h) Recipes [80].(8i) Seances [93].(8j) Screen recordings of online interactions [60].(8k) Sensory diaries [79].(8l) Texting [72].

3.3. Summary of Methods and Methodologies

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Howes, D.; Architecture of the Senses 2005. Sense of the City Exhibition Catalogue. Available online: https://www.david-howes.com/DH-research-sampler-arch-senses.htm (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Pink, S. Doing Sensory Ethnography; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4462-8759-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sensory Studies 2023. Available online: https://www.sensorystudies.org (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Grittner, A.; Sitter, K.C. The Role of Place in the Lives of Sex Workers: A Sociospatial Analysis of Two International Case Studies. Affilia 2020, 35, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J. Multiple Multi-Sensory Rooms: Myth Busting the Magic; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-367-34185-5. [Google Scholar]

- Howes, D. The Sensory Studies Manifesto: Tracking the Sensorial Revolution in the Arts and Human Sciences; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023; ISBN 978-1-4875-2863-8. [Google Scholar]

- Backman, C.; Demery-Varin, M.; Cho-Young, D.; Crick, M.; Squires, J. Impact of Sensory Interventions on the Quality of Life of Long-Term Care Residents: A Scoping Review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, L.; Passarelli, C.; Shepley, S.E.; Tigno, W. A Scoping Review: Sensory Interventions for Older Adults Living with Dementia. Dementia 2022, 21, 1416–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watling, R.; Hauer, S. Effectiveness of Ayres Sensory Integration® and Sensory-Based Interventions for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 69, 6905180030p1–6905180030p12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, L.; Guerra, N.; Ganz, L.; Ervin, D. Clinical Utility of Multisensory Environments for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74, 7401205060p1–7401205060p12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, I.-G.; Do, J.-H. Multisensory Balance Training for Unsteady Elderly People: A Scoping Review. Technol. Disabil. 2021, 33, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaltonen, T.; Raudaskoski, S. Storyworld Evoked by Hand-Drawn Maps. Soc. Semiot. 2011, 21, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldouby, H. Balancing on Shifting Ground: Migratory Aesthetics and Recuperation of Presence in Ori Gersht’s Video Installation on Reflection. Crossings J. Migr. Cult. 2019, 10, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen-Collinson, J.; Vaittinen, A.; Jennings, G.; Owton, H. Exploring Lived Heat, “Temperature Work,” and Embodiment: Novel Auto/Ethnographic Insights from Physical Cultures. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 2016, 47, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, C.; Gubrium, A. Bodies That Tell: Embodying Teen Pregnancy through Digital Storytelling. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2018, 43, 905–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, C. Video Diaries: Audio-Visual Research Methods and the Elusive Body. Vis. Stud. 2013, 28, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battesti, V.; Puig, N. “The Sound of Society”: A Method for Investigating Sound Perception in Cairo. Senses Soc. 2016, 11, 298–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botticello, J. From Documentation to Dialogue: Exploring New ‘Routes to Knowledge’ through Digital Image Making. Vis. Stud. 2016, 31, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, D.; Cook, N. The Epistemological and Ethical Value of Autophotography for Mobilities Research in Transcultural Contexts. Stud. Soc. Justice 2017, 11, 238–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C. Dance and Choreography as a Method of Inquiry. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2020, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cerulo, K.A. Scents and Sensibility: Olfaction, Sense-Making, and Meaning Attribution. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2018, 83, 361–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clerck, G.A.M. Creative Biographical Responses to Epistemological and Methodological Challenges in Generating a Deaf Life Story Telling Instrument. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2019, 14, 475–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, A.; Smith, L.; Collings, S.; Savage, I.D. Complexity Embodied: Using Body Mapping to Understand Complex Support Needs. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2018, 19, 162–185. [Google Scholar]

- Due, B.L.; Lange, S.B. Troublesome Objects: Unpacking Ocular-Centrism in Urban Environments by Studying Blind Navigation Using Video Ethnography and Ethnomethodology. Sociol. Res. Online 2018, 24, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duruz, J. Tastes of the “Mongrel” City Geographies of Memory, Spice, Hospitality and Forgiveness. Cult. Stud. Rev. 2013, 19, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbensgaard, C.L. Illuminights: A Sensory Study of Illuminated Urban Environments in Copenhagen. Space Cult. 2014, 18, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T. Reconnecting with Darkness: Gloomy Landscapes, Lightless Places. Reconectando Con Oscuridad Paisajes Sombríos Lugares Sin Luz Reconnecter Avec Obscurité Paysages Sombres Lieux Lumière. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2013, 14, 446–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aníbal, G.A. The Quilombola Movement: Sensing Futures in Afroindigenous Amazonia. Ethos 2020, 48, 336–356. [Google Scholar]

- Gieser, T. Sensing and Knowing Noises: An Acoustemology of the Chainsaw. Soc. Anthropol. Soc. 2019, 27, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenough, C. Visual Intimacies: Faith, Sexuality, Photography. Sex. Cult. 2018, 22, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankins, S. Multidimensional Israeliness and Tel Aviv’s Tachanah Merkazit: Hearing Culture in a Polyphonic Transit Hub. City Soc. 2013, 25, 282–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, J. Hearing Things and Dancing Numbers: Embodying Transformation, Topology at Tate Modern. Theory Cult. Soc. 2012, 29, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, S.; Lewis, C. Investigating Everyday Life in a Modernist Public Housing Scheme: The Implications of Residents’ Understandings of Well-Being and Welfare for Social Work. Br. J. Soc. Work 2018, 49, 806–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamstra, P.; Cook, B.; Edensor, T.; Kennedy, D.M. Re-casting Experience and Risk along Rocky Coasts: A Relational Analysis Using Qualitative GIS. Geogr. J. 2019, 185, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, M. Embodiment in Active Sport Tourism: An Autophenomenography of the Tour de France Alpine “Cols”. Sociol. Sport J. 2021, 38, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, K.E.Y. The Sensuous City: Sensory Methodologies in Urban Ethnographic Research. Ethnography 2015, 16, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, D.; Back, L. Fishmongers in a Global Economy: Craft and Social Relations on a London Market. Sociol. Res. Online 2012, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.L. Valuing the Bad and the Ugly: Tasting Agrobiodiversity Among the Indigenous Canela. Food Cult. Soc. 2017, 20, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natali, L.; Acito, G.; Mutti, C.; Anzoise, V. A Visual and Sensory Participatory Methodology to Explore Social Perceptions: A Case Study of the San Vittore Prison in Milan, Italy. Crit. Criminol. 2021, 29, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M. Walking, Well-Being and Community: Racialized Mothers Building Cultural Citizenship Using Participatory Arts and Participatory Action Research. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2018, 41, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M.; Hubbard, P. Walking, Sensing, Belonging: Ethno-Mimesis as Performative Praxis. Vis. Stud. 2010, 25, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J.; O’Neill, M. Walking in the Boboli Gardens in Florence: Toward a Transdisciplinary, Visual, Cultural, and Constellational Analyses of Medieval Sensibilities in the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Qual. Inq. 2022, 28, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, D.; Cachinho, H. The First Impression in the Urban Sonic Experience: Transitions, Attention, and Attunement. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2018, 100, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, L. Filmic Encounters: Multispecies Care and Sacrifice on Island Timor. Aust. J. Anthropol. 2021, 32, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño-Lakatos, G.; Navarret, B.; Lindenmeyer, C.; Genevois, H.; Barbosa-Magalhaes, I.; Corcos, M.; Letranchant, A. Music, Vibrotactile Mediation and Bodily Sensations in Anorexia Nervosa: “It’s like I can Really feel my Heart Beating”. Hum. Technol. 2020, 16, 372–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, S.; Hubbard, P.; O’Neill, M.; Radley, A. Walking across Disciplines: From Ethnography to Arts Practice. Vis. Stud. 2010, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, K.A. Multimodal Mapmaking: Working toward an Entangled Methodology of Place. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 2016, 47, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snake-Beings, E. The Liquid Midden: A Video Ethnography of Urban Discard in Boeng Trabaek Channel, Cambodia. Vis. Anthropol. 2020, 33, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinney, J. A Chance to Catch a Breath: Using Mobile Video Ethnography in Cycling Research. Mobilities 2011, 6, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, A. Arrival Stories: Using Participatory, Embodied, Sensory Ethnography to Explore the Making of an English City for Newly Arrived International Students. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 2015, 46, 544–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabi, E.; Rowsell, J. Towards Sensorial Approaches to Visual Research with Racially Diverse Young Men. Stud. Soc. Justice 2017, 11, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tan, Q.H. Scent-Orship and Scent-Iments on the Scent-Ual: The Relational Geographies of Smoke/Smell between Smokers and Non-Smokers in Singapore. Senses Soc. 2016, 11, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiainen, M. Sonic Technoecology: Voice and Non-Anthropocentric Survival in The Algae Opera. Aust. Fem. Stud. 2017, 32, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnqvist, M.; Holmberg, T. The Sensing Eye: Intimate Vision in Couple Dancing. Ethnography 2021, 14661381211038430, Unpublished work. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themen, K.; Popan, C. Auditory and Visual Sensory Modalities in the Velodrome and the Practice of Becoming a Track Cyclist. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2021, 57, 618–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, T.D. Music and Trance as Methods for Engaging with Suffering. Ethos 2020, 48, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arceño, M.A. Changing [Vitivini] Cultures in Ohio, USA, and Alsace, France: An Ethnographic Study of Terroir and the Taste of Place. Ph.D. Thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, C.J. Investigating the Lived Experience of an After-School Minecraft Club. Ph.D. Thesis, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bartos, A.E. Remembering, Sensing and Caring for Their Worlds: Children’s Environmental Politics in a Rural New Zealand Town. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, M.B. A Socioesthetics of Punk: Theorizing Personal Narrative, History, and Place. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, W. Public Hearings: Sonic Encounters and Social Responsibility in the New York City Subway System. Ph.D. Thesis, New York University, New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Budden, A. Moral Worlds and Therapeutic Quests: A Study of Medical Pluralism and Treatment-Seeking in the Lower Amazon. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, E.D. Multimodal Literacies of Cuban Artists Living in Habana, Cuba: Video Portraitures of Creativity as Action. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carrizo, L. Exiled Nostalgia and Musical Remembrance: Songs of Grief, Joy, and Tragedy among Iraqi Jews. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, R.Y. Mediating the Dharma, Attuning the Sensorium: Technologies of Embodiment and Personhood Among Nonliberal Buddhists in North America. Ph.D. Thesis, New York University, New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y. Politics of Tranquility: Religious Mobilities and Material Engagements of Tibetan Buddhist Nuns in Post-Mao China. Ph.D. Thesis, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Corral Paredes, C. “Being in the Wrong Place at the Wrong Time” Ethnographic Insights Into Experiences of Incarceration and Release From a Mexican Prison. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.A.B. Sense and Queerness: A Poetics of Erotic Delinquency and Belonging in Fortaleza, Brazil. Ph.D. Thesis, New York University, New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fantinato Geo de Siqueira, M. Resonances of Land: Silence, Noise, and Extractivism in the Brazilian Amazon. Ph.D. Thesis, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fiers, J.J. Paradoxes of Power in Competitive Youth Sport: Florida Junior Tennis. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Goldwert, I.C.W. Somatic Hope: Practice, Persuasion & the Body-Self in North American Yoga Therapy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y. Tasting Tea, Tasting China: Tearooms and the Everyday Culture in Dalian. Ph.D. Thesis, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Iwase, M. New Literacies, Japanese Youth, & Global Fast-Food Culture: Exploring Critical Youth Agencies. Master’s Thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, CA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Keleman Saxena, A. Out of the Field and Into the Kitchen: Agrobiodiversity, Food Security, and Food Culture in Cochabamba, Bolivia. Ph.D. Thesis, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kennell, J.L. The Senses and Suffering: Medical Knowledge, Spirit Possession, and Vaccination Programs in Aja. Ph.D. Thesis, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Minkoff, M.F. Making Sense of The Fort: Civically-Engaged Sensory Archaeology at Fort Ward and the Defenses of Washington. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Naidu, P. Sea-Change: Mambai Sensory Practices and Hydrocarbon Exploitation in Timor-Leste. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nkhabutlane, P. An Investigation of Basotho Culinary Practices and Consumer Acceptance of Basotho Traditional Bread. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, B. Sense Work: Inequality and the Labor of Connoisseurship. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pullum, L.B. Faithful/Traitor: Violence, Nationalism, and Performances of Druze Belonging. Ph.D. Thesis, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Quest, M.N. Portside Synaesthetics: Sensing the Politics of Place in Marseille. Ph.D. Thesis, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, R.R. (Re)Ordering and (Dis)Ordering of Street Trade: The Case of Recife, Brazil. Ph.D. Thesis, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson, K. Pimento Cheese and Podcasts: Producing and Consuming Stories about Food in the Contemporary U.S. South. Ph.D. Thesis, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.E. Tensions: Thinking Through Hand Knitting. Master’s Thesis, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schug, S.E. Speaking and Sensing the Self in Authentic Movement: The Search for Authenticity in a 21st Century White Urban Middle-Class Community. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seiler, J.M. Sensing Security Through Contemporary Art and Ethnographic Encounters. Ph.D. Thesis, Ohio University, Athens, OH, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver, M.L. The Making of a Fishing Pueblo: Sustaining Place in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, S.M. What Comes Between Coca and Cocaine: Transformation and Haunting in the Peruvian Amazon. Ph.D. Thesis, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trocchia-Balkits, L.M. A Hipstory of Food, Love, and Chaosmos at the Rainbow Gathering of the Tribes. Ph.D. Thesis, Ohio University, Athens, OH, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa Garzón, A.M. After Flavor: An Ethnographic Study of Science, Industry, and Gastronomy. Ph.D. Thesis, The New School, New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yerby, E. Spectral Bodies of Evidence: The Body as Medium in American Spiritualism. Ph.D. Thesis, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gobo, G. Doing Ethnography; SAGE Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4129-1921-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C.; Adams, T.E.; Bochner, A.P. Autoethnography: An Overview. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2011, 12, 273–290. [Google Scholar]

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | (multi-sensor * OR multisensor * OR multimod * OR sensory OR sensorial OR embodied) AND (research OR method * OR storytelling OR mode * OR ethnography) |

|

| Author(s) | Country | Article Purpose | Participant Characteristics | Discipline | Study Methodology | Methods |

| 1. Ethnographic-Based Methodologies | 2. Phenomenology-Based Methodologies | 3. Participatory-Based Methodologies | 4. Other Methodologies | 5. Not Identified/Clear |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General (ethnography): 18 Sensory:11 Blended Sensory: 6 Autoethnography: 6 Visual: 3 Video: 1 Other: 9 | Phenomenology: 1 Sensory: 1 Ethnography: 5 | Participatory action: 2 Sensory and visual: 1 Arts-based: 1 Ethnography: 1 | Mixed methods: 2 Multimodal clinical study: 1 Digital storytelling: 1 Narrative inquiry: 1 Case study: 1 Portraiture: 1 Technoecology: 1 | 5 |

| Total: 55 | Total: 7 | Total: 5 | Total: 8 | Total: 5 |

| 1. Kinesthetic | 2. Mapping | 3. Sound | 4. Smell | 5. Taste | 6. Touch | 7. Visual | 8. Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42 | 13 | 32 | 7 | 11 | 11 | 45 | 24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sitter, K.C.; Haney, C.-A.; Herrera, A.; Pabia, M.; Schick, F.C.; Squires, S. Sensory Methodologies and Methods: A Scoping Review. Societies 2025, 15, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060160

Sitter KC, Haney C-A, Herrera A, Pabia M, Schick FC, Squires S. Sensory Methodologies and Methods: A Scoping Review. Societies. 2025; 15(6):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060160

Chicago/Turabian StyleSitter, Kathleen C., Carly-Ann Haney, Ana Herrera, Mica Pabia, Fiona C. Schick, and Stacey Squires. 2025. "Sensory Methodologies and Methods: A Scoping Review" Societies 15, no. 6: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060160

APA StyleSitter, K. C., Haney, C.-A., Herrera, A., Pabia, M., Schick, F. C., & Squires, S. (2025). Sensory Methodologies and Methods: A Scoping Review. Societies, 15(6), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060160