Clinical Practice Guidelines as a Medical Profession Government Technology in Medellín, Colombia

Abstract

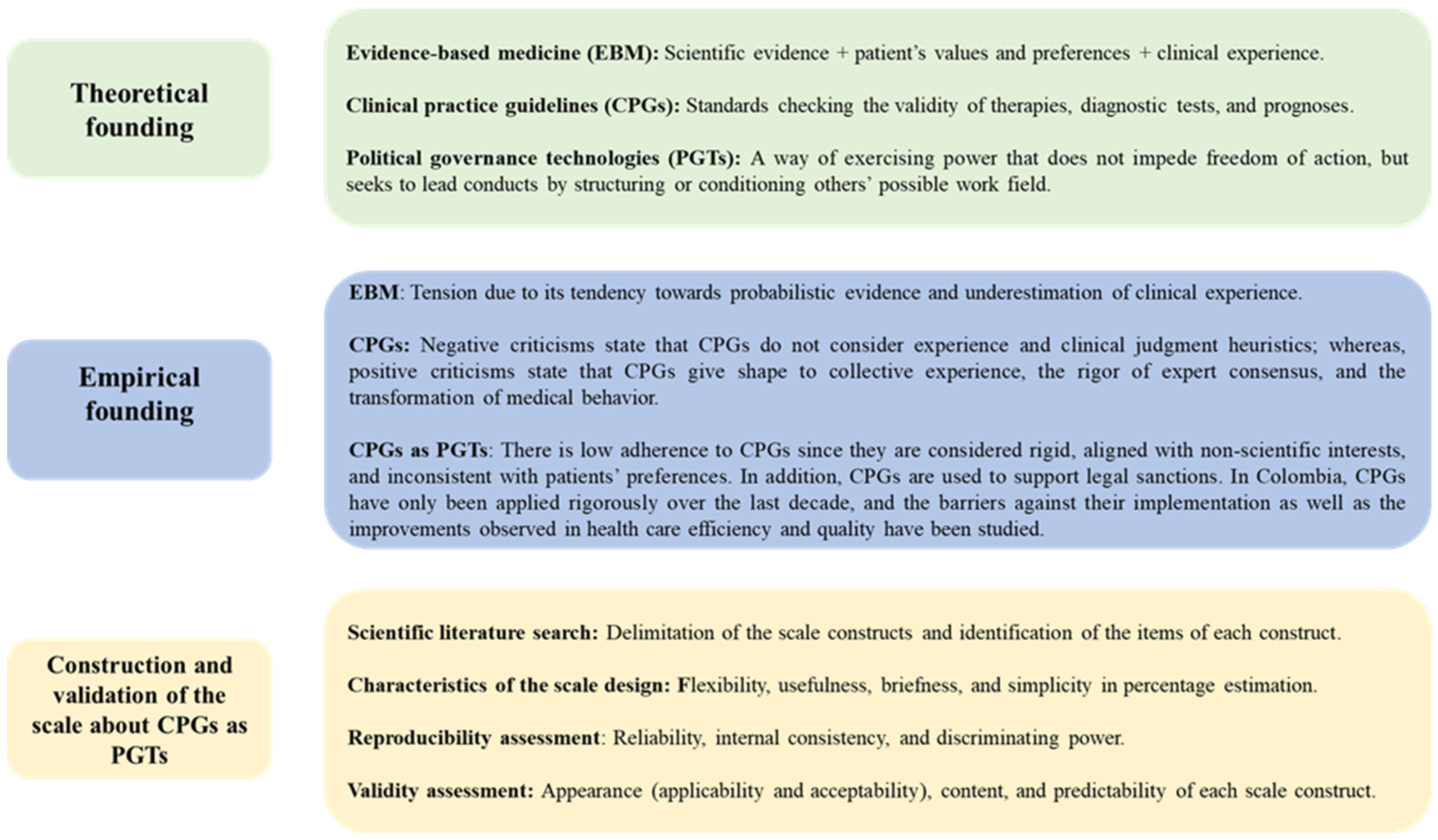

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Type of Study: Cross-Sectional

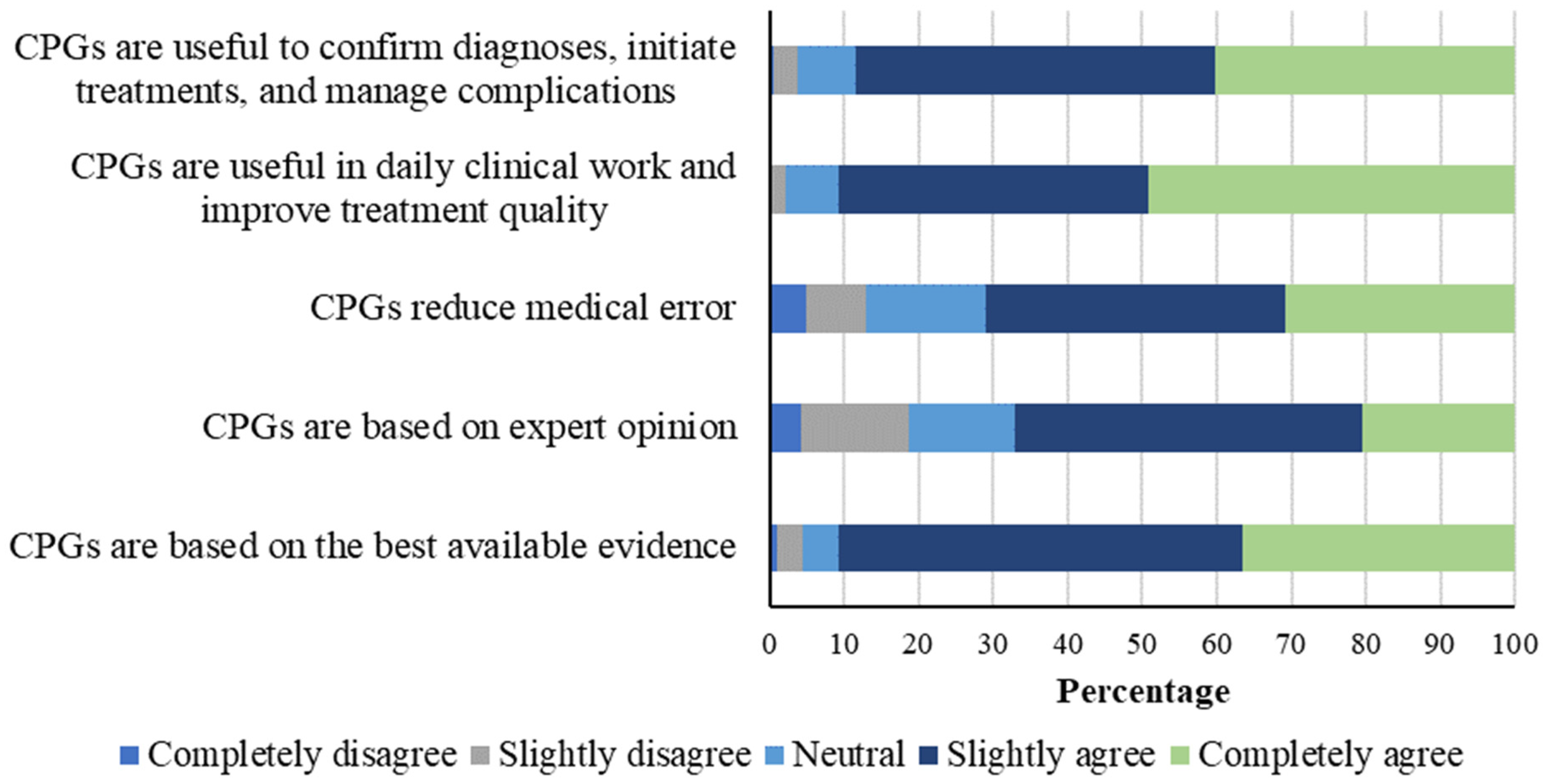

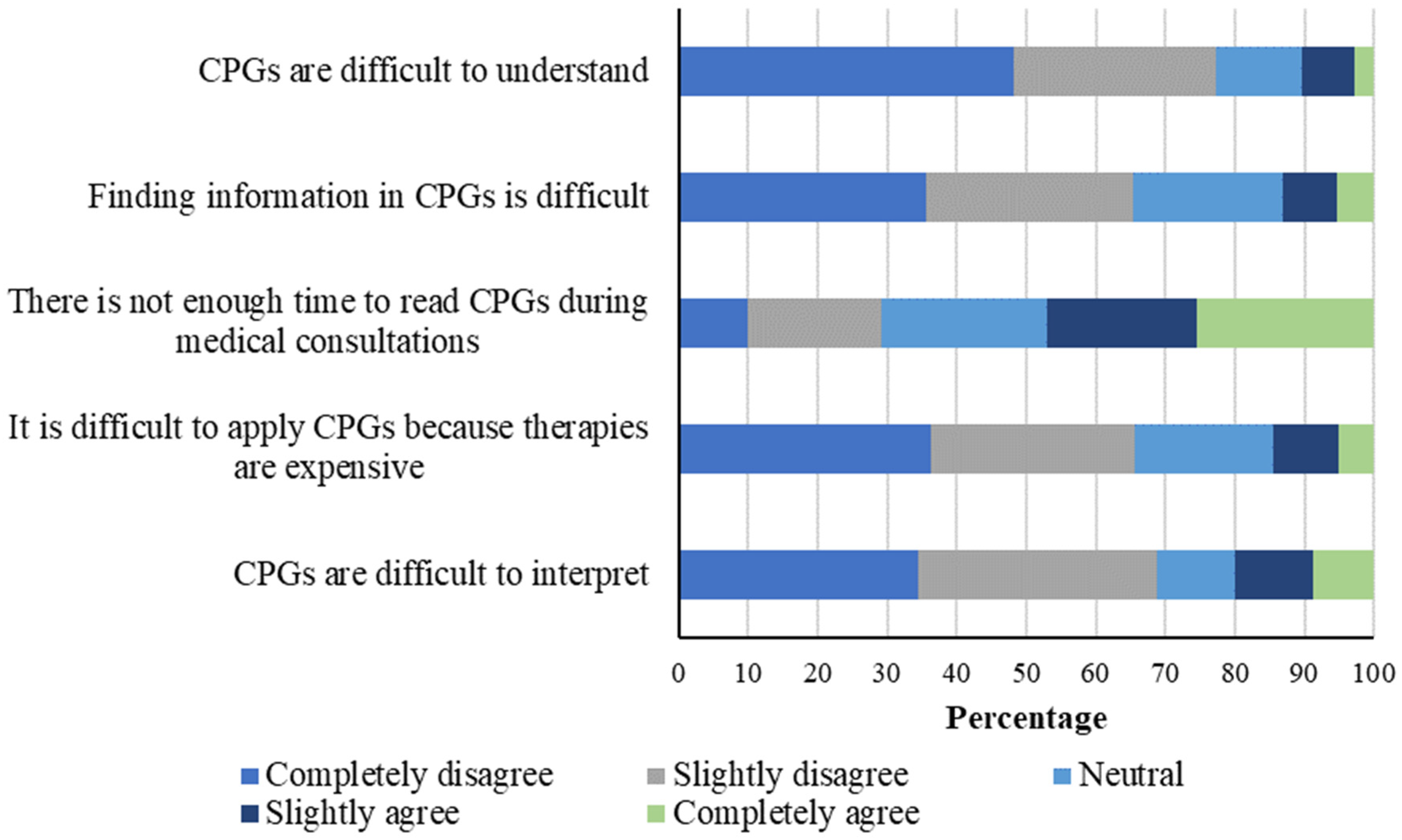

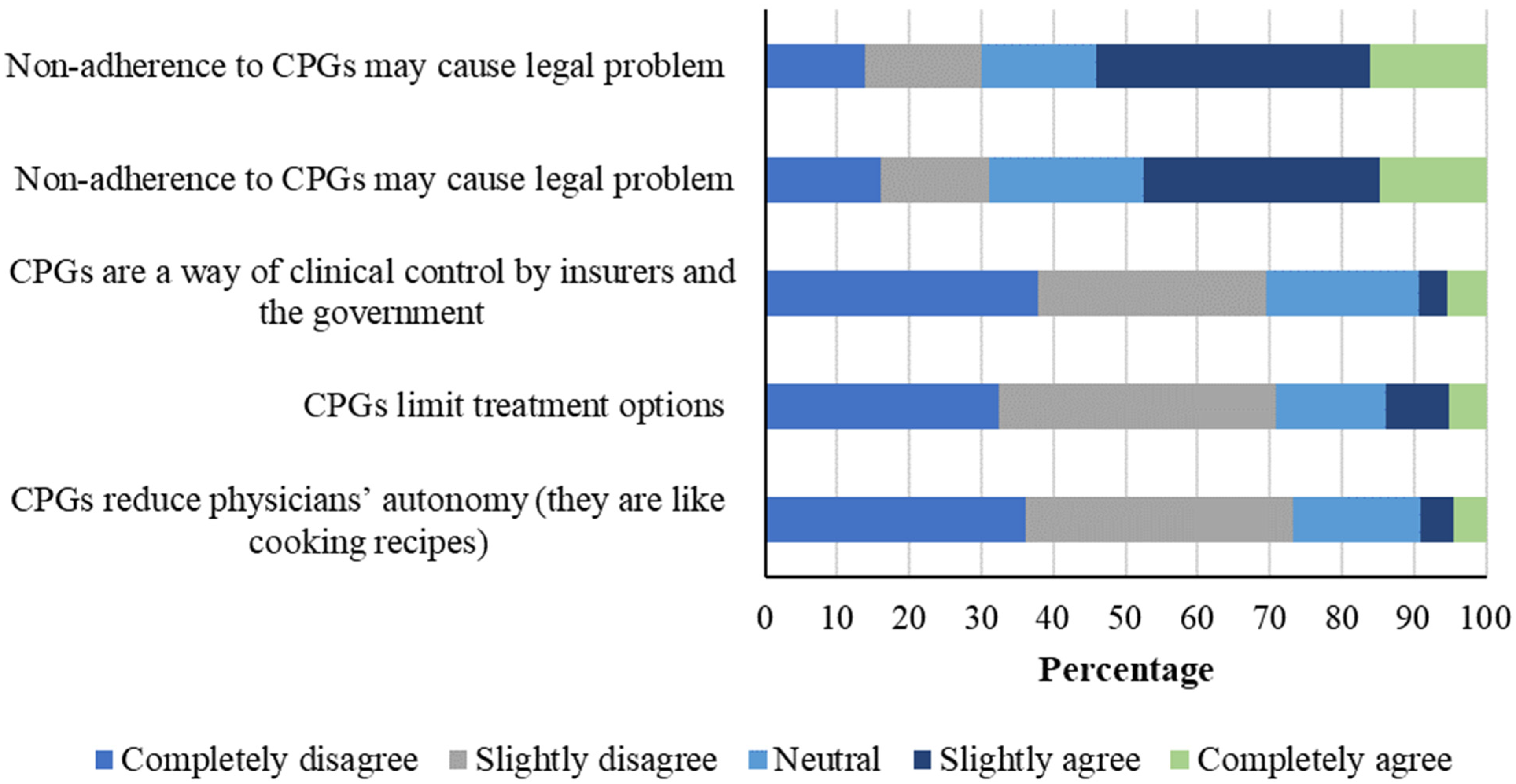

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. General Perception of CPGs

4.2. CPGs Facilitators and Barriers

4.3. Clinical Practice Guidelines and Professional Autonomy

4.4. Effects of CPGs on the Patient–Physician Relationship

4.5. Limitations and Strengths of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sackett, D.L.; Rosenberg, W.M.C.; Gray, J.A.M.; Haynes, R.B.; Richardson, W.S. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996, 312, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montori, V.M.; Guyatt, G.H. What is evidence-based medicine? Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2002, 31, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.; Cairns, J.; Churchill, D.; Cook, D.; Haynes, B.; Hirsh, J.; Irvine, J.; Levine, M.; Levine, M.; Nishikawa, J.; et al. Evidence-Based Medicine: A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA 1992, 268, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykhalovskiy, E.; Weir, L. The problem of evidence-based medicine: Directions for social science. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickersin, K.; Straus, S.E.; Bero, L.A. Evidence based medicine: Increasing, not dictating, choice. BMJ 2007, 334 (Suppl. 1), s10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Berg, M. The Gold Standard. The Challenge of Evidence Based Medicine and Standardization in Health Care; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, M. Turning a Practice into a Science: Reconceptualizing Postwar Medical Practice. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1995, 25, 437–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, M.R. The challenge of evidence in clinical medicine. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2010, 16, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaapen, L. Being ‘evidence-based’ in the absence of evidence: The management of non-evidence in guideline development. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2013, 43, 681–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A.R. Clinical Judgment Revisited: The Distraction of Quantitative Models. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 120, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, R.S.; Wilson, M.C.; Tunis, S.R.; Bass, E.B.; Guyatt, G. Users’ guides to the medical literature. VIII. How to use clinical practice guidelines. A. Are the recommendations valid? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1995, 274, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisz, G.; Cambrosio, A.; Keating, P.; Knaapen, L.; Schlich, T.; Tournay, V.J. The Emergence of Clinical Practice Guidelines. Milbank Q. 2007, 85, 691–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, E.; White, K. Evidence-Based Medicine, the Medical Profesión and Health Policy; Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rodwin, M.A. The Politics of Evidence-Based Medicine. J. Health Politics Policy Law 2001, 26, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D.; Murray, S.J.; Perron, A.; Rail, G. Deconstructing the evidence-based discourse in health sciences: Truth, power and fascism. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2006, 4, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankford, D.M. Scientism and Economism in the Regulation of Health Care. J. Health Politics Policy Law 1994, 19, 773–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D. Clinical sense and clinical science. Soc. Sci. Med. 1977, 11, 599–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D. Clinical autonomy, individual and collective: The problem of changing doctors’ behaviour. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 55, 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M. Whither our art? Clinical wisdom and evidence-based medicine. Med. Health Care Philos. 2002, 5, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykhalovskiy, E. Evidence-Based Medicine: Ambivalent Reading and the Clinical Recontextualization of Science. Health Interdiscip. J. Soc. Study Health Illn. Med. 2003, 7, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, H. Accounting for EBM: Notions of evidence in medicine. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 2633–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derksen, F.; Bensing, J.; Kuiper, S.; van Meerendonk, M.; Lagro-Janssen, A. Empathy: What does it mean for GPs? A qualitative study. Fam. Pract. 2015, 32, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanemaayer, A. The Impossible Clinic. A Critical Sociology of Evidence-Based Medicine; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Congreso de Colombia. Ley 1438. 2023. Available online: www.minsalud.gov.co/Normatividad_Nuevo/LEY%201438%20DE%202011.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social—República de Colombia. Clinical practice guidelines CPGs [Guías de práctica clínica GPC]. Available online: http://gpc.minsalud.gov.co/gpc/SitePages/buscador_gpc.aspx (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Sánchez-Duque, J.; Méndez-Hernández, P.; Mendieta, G.; Rodríguez, J.; Gómez-González, J. Educación en salud basada en la evidencia: Una perspectiva de estudiantes de medicina colombianos. RHCS 2020, 3, 159–160. [Google Scholar]

- Patiño-Lugo, D.F.; Pastor Durango, M.d.P.; Lugo-Agudelo, L.H.; Posada Borrero, A.M.; Ciro Correa, V.; Plata Contreras, J.A.; Vera Giraldo, C.Y.; Aguirre-Acevedo, D.C. Implementation of the clinical practice guideline for individuals with amputations in Colombia: A qualitative study on perceived barriers and facilitators. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Díaz, N.; Duarte Osorio, A.; Gómez Restrepo, C.; Bohórquez Peñaranda, A.P. Implementacion de la guía de práctica clínica para el manejo de adultos con esquizofrenia en Colombia. Rev. Colomb. De Psiquiatr. 2016, 45, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Díaz, O.L.; Esparza-Bohórquez, M.; Jaimes-Valencia, M.L.; Granados-Oliveros, L.M.; Bonilla-Marciales, A.; Medina-Tarazona, C. Experiencia en la implantación y consolidación de las Guías de buenas prácticas de la Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO) en el ámbito clínico y académico en Colombia. Enfermería Clínica 2020, 30, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Moreno, J.H.; Romero Vergara, A.J.; de Alba De Moya, D.D.J.; Jaramillo Rojas, H.J.; Díaz Rojas, C.M.; Ciapponi, A. Evaluación de herramientas de implementación de la Guía de Práctica Clínica de infecciones de transmisión sexual. Rev. Panam. De Salud Pública 2017, 41, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASCOFAME. Facultades Afiliadas. 2023. Available online: https://ascofame.org.co/web/facultades-afiliadas/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Ministerio de Educación Nacional. Bases Consolidadas. 2023. Available online: https://snies.mineducacion.gov.co/portal/ESTADISTICAS/Bases-consolidadas/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Indicadores Básicos de Talento Humano. 2020. Available online: https://www.sispro.gov.co/observatorios/ontalentohumano/Paginas/Observatorio-de-Talento-Humano-en-Salud.aspx (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Hurwitz, B. Clinical Guidelines and the Law. Negligence, Discretion, and the Judgment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, B.; Haines, A. Getting research findings into practice: Barriers and bridges to evidence based clinical practice. BMJ 1998, 317, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taba, P.; Rosenthal, M.; Habicht, J.; Tarien, H.; Mathiesen, M.; Hill, S.; Bero, L. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of clinical practice guidelines: A cross-sectional survey among physicians in Estonia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Li, Z.; Han, F.; Huang, D.; Huang, Q.; Cao, Y.; Weng, H.; Zeng, X.-T.; Wang, X.; Shang, H.-C. Barriers and enablers for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines in China: A mixed-method study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, H.; Hashimoto, H.; Kiuchi, T. The evolving concept of “patient-centeredness” in patient–physician communication research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 96, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Sanchez, P.; Gaitan, H. Guías de práctica clínica en Colombia. Rev. Colomb. De Obstet. Y Ginecol. 2013, 64, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, E.A.; Asch, S.M.; Adams, J.; Keesey, J.; Hicks, J.; DeCristofaro, A.; Kerr, E.A. The Quality of Health Care Delivered to Adults in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2635–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.M.; Dellinger, R.P.; Townsend, S.R.; Linde-Zwirble, W.T.; Marshall, J.C.; Bion, J.; Schorr, C.; Artigas, A.; Ramsay, G.; Beale, R.; et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2010, 36, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldugieman, T.; Alanezi, R.; Alshammari, W.M.G.; Al-Shamary, Y.W.Z.; Alqahtani, M.; Alreshidi, F. Knowledge, attitude and perception toward evidence-based medicine among medical students in Saudi Arabia: Analytic cross-sectional study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, K.; Sedaghati, F. Knowledge, attitude, and practices among Iranian neurologists toward evidence-based medicine. Iran J. Neurol. 2017, 16, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Djulbegovic, B.; Guyatt, G.H. Progress in evidence-based medicine: A quarter century on. Lancet 2017, 390, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, N. Políticas de Vida. Biomedicine, Poder y Subjetividad en el Siglo XXI; Editorial Universitaria: La Plata, Argentina, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Palacio, A.C.A. Editorial. Iatreia. 2017. 29(4-S). Palacio-Acosta CA. Editorial. Iatreia [Internet]. 15 de mayo de 2017 [citado 3 de marzo de 2025]; 29(4-S2). Available online: https://revistas.udea.edu.co/index.php/iatreia/article/view/327830 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Timmermans, S. From Autonomy to Accountability: The role of clinical practice guidelines in professional power. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2005, 48, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M. Problems and promises of the protocol. Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 44, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A. Risk, government and the new public health. In Petersen y Robin Bunton. Foucault, Health and Medicine; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ardila-Sierra, A.; Abadía-Barrero, C. Medical labour under neoliberalism: An ethnographic study in Colombia. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, N.; Miller, P. Political power beyond the State: Problematics of government. Br. J. Sociol. 2010, 61 (Suppl. 1), 271–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendieta Gonzalez, D.; Jaramillo, C.E. El Sistema general de seguridad social en salud en Colombia. Universal, pero ineficiente: A propósito de los veinticinco años de su creación. Rev. Latinoam. Derecho Soc. 2019, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C. El hospital como empresa: Nuevas práticas, nuevos trabajadores. Univ. Psychol. 2007, 6, 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, D. Professionalism, Indeterminacy and the EBM Project. BioSocieties 2007, 2, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Kolker, E.S. Evidence-based medicine and the reconfiguration of medical knowledge. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2004, 45, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hershey, N. The defensive practice of medicine. Myth or reality. Milbank Mem. Fund Q. 1972, 50, 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Mauck, A. The Promises and Pitfalls of Evidence-Based Medicine. Health Aff. 2005, 24, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstein, A.S. On the origins and development of evidence-based medicine and medical decision making. Inflamm. Res. 2004, 53, S184–S189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Légaré, F.; Simmons, M.B.; McNamara, K.; McCaffery, K.; Trevena, L.J.; Hudson, B.; Glasziou, P.P.; del Mar, C.B. Shared decision making: What do clinicians need to know and why should they bother? Med. J. Aust. 2014, 201, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrow, L.; Wartman, S.A.; Brock, D.W. Science, ethics, and the making of clinical decisions. Implications for risk factor intervention. JAMA 1988, 259, 3161–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia Tecnología e Innovación—Colciencias. Guía de Práctica Clínica Para la Prevención, Diagnóstico, Tratamiento y Rehabilitación de la Falla Cardíaca en Población Mayor de 18 años Clasificación B, C y D. Guía Completa. 2016. Guía No. 53. 2023. Available online: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/CA/gpc-rehabilitacion-falla-cardiaca-poblacion-mayor-18-anos-b-c-d.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social—Colciencias Guía de Práctica Clínica. Hipertensión Arterial Primaria (HTA)—2013 Guía No. 18. 2023. Available online: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/INEC/IETS/GPC_Completa_HTA.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Foucault, M. El sujeto y el poder. Rev. Mex. Sociol. 1988, 50, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lambda | Item–Other Domain Correlation | |||||||

| General Perception of CPGs | Item–Domain Correlation | Facilitators and Barriers | Professional Autonomy | Patient–Physician Relationship | ||||

| Based on the best available evidence | 0.657 | 0.523 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.175 ** | 0.220 ** | |||

| Based on experts’ opinion | 0.433 | 0.165 ** | −0.010 | −0.236 ** | −0.113 * | |||

| Reduce medical error | 0.432 | 0.630 ** | 0.238 ** | −0.041 | 0.278 ** | |||

| Useful for clinical work and improve treatment quality | 0.866 | 0.726 ** | 0.323 ** | 0.227 ** | 0.353 ** | |||

| Useful to confirm diagnoses, initiate treatments and manage complications | 0.799 | 0.581 ** | 0.140 * | 0.122 * | 0.219 ** | |||

| % variance | 43.8% | |||||||

| % success of content validity | 100% (5/5) | |||||||

| % success of internal consistency | 80% (4/5) | |||||||

| % success of discriminating power | 100% (15/15) | |||||||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.676 | |||||||

| Facilitators and Barriers | Lambda | Item–Domain Correlation | General Perception | Professional Autonomy | Patient–Physician Relationship | |||

| Their interpretation is difficult | 0.525 | 0.739 ** | 0.244 ** | 0.330 ** | 0.268 ** | |||

| Their interpretation is difficult because treatments are expensive | 0.561 | 0.696 ** | 0.079 | 0.503 ** | 0.363 ** | |||

| There is no time to read CPGs during medical consultations | 0.203 | 0.563 ** | 0.304 ** | 0.104 | 0.373 ** | |||

| Finding information in CPGs is difficult | 0.569 | 0.738 ** | 0.207 ** | 0.329 ** | 0.316 ** | |||

| They are not easily understood | 0.777 | 0.784 ** | 0.223 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.478 ** | |||

| % variance | 52.7% | |||||||

| % success of content validity | 80% (4/5) | |||||||

| % success of internal consistency | 100% (5/5) | |||||||

| % success of discriminating power | 100% (15/15) | |||||||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.780 | |||||||

| Professional Autonomy | Lambda | Item–Domain Correlation | General Perception | Facilitators and Barriers | Patient–Physician Relationship | |||

| CPGs reduce physicians’ autonomy (they are like cook recipes) | 0.803 | 0.623 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.486 ** | 0.517 ** | |||

| CPGs limit treatment options | 0.814 | 0.636 ** | 0.154 ** | 0.382 ** | 0.563 ** | |||

| CPGs are a way of ensuring clinical control by insurance companies and the government | 0.769 | 0.675 ** | 0.192 ** | 0.394 ** | 0.373 ** | |||

| Non-adherence to CPGs may cause labor conflicts | 0.566 | 0.668 ** | −0.142 * | 0.133 * | 0.019 | |||

| Non-adherence to CPGs may cause legal conflicts | 0.545 | 0.615 ** | −0.202 ** | 0.151 ** | 0.067 | |||

| % variance | 50.3% | |||||||

| % success of content validity | 100% (5/5) | |||||||

| % success of internal consistency | 100% (5/5) | |||||||

| % success of discriminating power | 100% (15/15) | |||||||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.778 | |||||||

| Patient–Physician Relationship | Lambda | Item–Domain Correlation | General Perception | Facilitators and Barriers | Autonomy | |||

| Patients do not like it when physicians follow CPGs | 0.734 | 0.688 ** | 0.265 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.283 ** | |||

| CPGs hinder individual patient approach | 0.689 | 0.645 ** | 0.213 ** | 0.500 ** | 0.502 ** | |||

| CPGs address standard patients and do not reflect reality | 0.754 | 0.662 ** | 0.294 ** | 0.483 ** | 0.408 ** | |||

| CPGs are an obstacle against feeling empathy towards patients | 0.695 | 0.736 ** | 0.238 ** | 0.323 ** | 0.191 ** | |||

| Sometimes, it is difficult to align CPGs with patients’ preferences | 0.779 | 0.764 ** | 0.124 * | 0.294 ** | 0.236 ** | |||

| % variance | 53.4% | |||||||

| % success of content validity | 100% (5/5) | |||||||

| % success of internal consistency | 100% (5/5) | |||||||

| % success of discriminating power | 100% (15/15) | |||||||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.786 | |||||||

| Rho Correlation Coefficients Between Constructs | General Perception | Facilitators and Barriers | Professional Autonomy | Patient–Physician Relationship | ||||

| General perception | 1 | 0.347 ** | 0.074 | 0.330 ** | ||||

| Facilitators and barriers | 0.347 ** | 1 | 0.436 ** | 0.477 ** | ||||

| Professional autonomy | 0.074 | 0.436 ** | 1 | 0.416 ** | ||||

| Patient–physician relationship | 0.330 ** | 0.477 ** | 0.416 ** | 1 | ||||

| n | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Women | 136 | 43.7 (38.3–49.3) |

| Men | 175 | 56.3 (50.7–61.7) |

| Age group | ||

| 20 to 40 years | 195 | 62.7 (57.2–67.9) |

| >40 years | 116 | 37.3 (32.1–42.8) |

| General or specialized physician | ||

| General physician | 235 | 75.6 (70.6–80.1) |

| Specialized physician | 76 | 24.4 (19.9–29.4) |

| Work experience (years) | ||

| One year | 51 | 16.4 (12.6–20.8) |

| Two to ten years | 105 | 33.8 (28.7–39.1) |

| More than ten years | 155 | 49.8 (44.3–55.4) |

| CPGs use | ||

| Never or seldom | 47 | 15.1 (11.5–19.4) |

| Always or almost always | 264 | 84.9 (80.6–88.5) |

| Number of CPGs known | ||

| One to two | 21 | 6.8 (4.4–9.9) |

| Three to four | 58 | 18.6 (14.6–23.3) |

| More than four | 229 | 73.6 (68.5–78.3) |

| None | 3 | 1.0 (0.3–2.6) |

| General Perception | Facilitators and Barriers | Professional Autonomy | Patient–Physician Relationship | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 70.0 (60.0–75.0) | 65.0 (50.0–80.0) | 60.0 (50.0–75.0) | 65,0 (50,0–80,0) |

| Men | 75.0 (65.0–80.0) | 72.5 (55.0–85.0) | 60.0 (50.0–70.0) | 65.0 (60.0–80.0) |

| p-value | <0.001 ** | 0.035 ** | 0.875 | 0.338 |

| Age group | ||||

| 20–40 years | 70.0 (60.0–80.0) | 65.0 (50.0–80.0) | 60.0 (50.0–75.0) | 65.0 (55.0–75.0) |

| >40 years | 75 (65.0–80.0) | 70.0 (60.0–82.5) | 60.0 (50.0–75.0) | 70.0 (55.0–85.0) |

| p-value | 0.105 | 0.032 ** | 0.728 | 0.017 ** |

| General or specialized physician | ||||

| General physician | 70.0 (60.0–80.0) | 70.0 (55.0–80.0) | 60.0 (50.0–75.0) | 65.0 (55.0–80.0) |

| Specialized physician | 75.0 (65.0–80.0) | 70.0 (60.0–85.0) | 60.0 (50.0–75.0) | 67.5 (57.5–90.0) |

| p-value | 0.071 | 0.092 | 0.575 | 0.297 |

| Work experience (years) | ||||

| One year | 70.0 (60.0–80.0) | 62.5 (45.0–75.0) | 60.0 (52.5–77.5) | 65.0 (50.0–75.0) |

| Two to ten years | 70.0 (65.0–75.0) | 70.0 (55.0–85.0) | 60.0 (50.0–75.0) | 65.0 (55.0–75.0) |

| More than ten years | 75.0 (65.0–80.0) | 70.0 (60.0–80.0) | 60.0 (50.0–75.0) | 70.0 (55.0–80.0) |

| p-value | 0.145 | 0.035 ** | 0.737 | 0.420 |

| Frequency of CPGs use in medical practice | ||||

| Always or almost always | 65.0 (60.0–75.0) | 60.0 (45.0–70.0) | 55.0 (50.0–70.0) | 60.0 (45.0–75.0) |

| Seldom or never | 70.0 (65.0–80.0) | 70.0 (55.0–85.0) | 60.0 (50.0–75.0) | 70.0 (55.0–80.0) |

| p-value | 0.008 ** | 0.003 ** | 0.135 | 0.002 ** |

| Number of CPGs known | ||||

| None | 60.0 (60.0–65.0) | 80.0 (75.0–80.0) | 100.0 (90.0–100.0) | 100.0 (65.0–100) |

| One to two | 65.0 (55.0–70.0) | 60.0 (30.0–65.0) | 55.0 (42.5–70.0) | 55.0 (40.0–65.0) |

| Three to four | 65.0 (60.0–80.0) | 60.0 (50.0–72.5) | 65.0 (50.0–75.0) | 55.0 (45.0–75.0) |

| More than four | 75.0 (65.0–80.0) | 70.0 (55.0–85.0) | 60.0 (50.0–75.0) | 70.0 (60.0–85.0) |

| p-value | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | 0.026 ** | <0.001 ** |

| Regression Model | Regression Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Perception of CPGs construct | |

| Sex | 0.140 ** |

| Number of CPGs known | 0.105 ** |

| Facilitators and barriers score | 0.241 ** |

| Autonomy score | −0.161 ** |

| Patient–physician relationship score | 0.242 ** |

| Facilitators and barriers score | |

| Years of experience | 0.098 ** |

| CPGs use | 0.081 ** |

| Perception of CPGs score | 0.191 ** |

| Patient–physician relationship score | 0.306 ** |

| Autonomy score | 0.292 ** |

| Professional autonomy construct | |

| Perception of CPGs score | −0.155 ** |

| Facilitators and barriers score | 0.342 ** |

| Patient–physician relationship score | 0.292 ** |

| Patient–physician relationship construct | |

| Number of CPGs known | 0.191 ** |

| Perception of CPGs score | 0.186 ** |

| Facilitators and barriers score | 0.284 ** |

| Autonomy score | 0.255 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Estrada-Mesa, D.A.; Higuita-Gutiérrez, L.F.; Cardona-Arias, J.A. Clinical Practice Guidelines as a Medical Profession Government Technology in Medellín, Colombia. Societies 2025, 15, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060147

Estrada-Mesa DA, Higuita-Gutiérrez LF, Cardona-Arias JA. Clinical Practice Guidelines as a Medical Profession Government Technology in Medellín, Colombia. Societies. 2025; 15(6):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060147

Chicago/Turabian StyleEstrada-Mesa, Diego Alejandro, Luis Felipe Higuita-Gutiérrez, and Jaiberth Antonio Cardona-Arias. 2025. "Clinical Practice Guidelines as a Medical Profession Government Technology in Medellín, Colombia" Societies 15, no. 6: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060147

APA StyleEstrada-Mesa, D. A., Higuita-Gutiérrez, L. F., & Cardona-Arias, J. A. (2025). Clinical Practice Guidelines as a Medical Profession Government Technology in Medellín, Colombia. Societies, 15(6), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060147