Abstract

This study addresses the dual sociological challenges of the silver digital divide and intergenerational estrangement in aging societies. Through a Participatory Action Research project, it explores and evaluates the AI-Enhanced Intergenerational Digital Inclusion (AI-IDI) framework as a mechanism for fostering social cohesion. Findings indicate that socio-emotional scaffolding from students, rather than technical instruction, was instrumental in reducing older adults’ technology anxiety, while students’ civic responsibility increased in line with the quality of collaboration. Interpreting these findings through the lens of Digital Symbiosis highlights how youth’s digital fluency and elders’ life wisdom can function as mutually reinforcing assets. Positioned as conceptual development and exploratory empirical research, this study reframes AI not as a mere tool but as a mediating resource for dialogue and solidarity. It contributes to sociological debates on technology and intergenerational relations while offering a transferable model for advancing digital equity and community cohesion.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.1.1. Beyond the Hype: Sociological Concerns on GenAI

The rise of Generative AI (GenAI) in higher education has triggered polarized debates that often vacillate between utopian promises of personalized learning [1] and dystopian fears of academic erosion [2]. Yet, such technology-centric framings risk obscuring deeper sociological questions: how does AI reshape patterns of knowledge production, social trust, and inequality? Critical sociology of technology [3,4] suggests that AI should not be examined merely as a neutral tool but as a socio-technical phenomenon embedded in relations of power, cultural values, and social reproduction. This study adopts such a perspective, moving beyond the “hype cycle” [5] to interrogate the substantive social and educational value of AI in community and intergenerational contexts.

At the same time, critical scholars caution that AI’s transformative potential is accompanied by systemic risks. As Noble [6] argues, algorithmic bias and data asymmetry can reinforce existing social inequalities, particularly when AI systems are deployed without ethical oversight. Recognizing these pitfalls, this study frames Digital Symbiosis as a normative response—one that emphasizes fairness, inclusivity, and reflexivity in human–AI collaboration.

Rather than celebrating technological harmony, it highlights the moral responsibility of educators and designers to ensure that AI serves as a medium for social cohesion and justice, not as a mechanism of exclusion or control.

1.1.2. The Convergence of Global Megatrends

This inquiry is situated at the intersection of three global megatrends: irreversible population aging, the accelerating AI-driven digital transformation, and the growing importance of higher education’s “third mission” of civic and community engagement [7,8]. The United Nations (2023) projects that one in six people worldwide will be over age 65 by 2050 [9], while UNESCO’s (2021) [10] Recommendation on the Ethics of AI highlights the urgency of ensuring human-centered and inclusive applications of emerging technologies. These dynamics align with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG4 (quality education) and SDG10 (reducing inequalities). In both the Global North and the Global South, the dual pressures of aging societies and digital transitions foreground the need for educational institutions to act not only as transmitters of knowledge but also as mediators of social inclusion and agents of digital equity.

1.1.3. The Dual Challenges of a Divided Society

Within this landscape, two interconnected challenges have become increasingly salient in aging societies: the widening silver digital divide and the deepening intergenerational distance. The former limits older adults’ access to digital resources and civic participation [11], while the latter weakens community cohesion and intergenerational solidarity [12]. Existing initiatives often address these issues separately—digital literacy programs emphasize skills training, whereas intergenerational projects overlook technological inclusion.

This study introduces the AI-Enhanced Intergenerational Digital Inclusion (AI-IDI) framework as an integrated response, positioning AI as a catalyst for reciprocity and social justice that bridges both divides.

1.2. Research Objectives: A Framework for Action and Contribution

The overarching aim of this study is to construct, implement, and evaluate an integrated framework that responds to the dual challenges of digital inequality and intergenerational estrangement in aging societies. By positioning AI not as a neutral technical instrument but as a socio-educational catalyst, the study seeks to advance both theoretical understanding and practical strategies for fostering digital equity and social cohesion. Specifically, it pursues four interrelated objectives:

Theoretical Integration: To synthesize and extend theories of intergenerational solidarity [12], digital capital [11], and constructivist pedagogy to develop the AI-Enhanced Intergenerational Digital Inclusion (AI-IDI) framework. This framework interprets digital inclusion as a matter of social justice and civic participation, rather than solely as a technical literacy issue.

Methodological Innovation: To employ Participatory Action Research (PAR) [13,14] as a collaborative pathway for designing, implementing, and iteratively refining the AI-IDI framework in authentic community contexts, thereby ensuring cultural relevance and social legitimacy.

Pedagogical Application: To design and deliver a university general education course that operationalizes the AI-IDI framework, fostering reciprocal intergenerational learning, critical AI literacy, and civic responsibility, while also exemplifying higher education’s “third mission” of community engagement.

Societal and Policy Contribution: To provide a replicable model that informs University Social Responsibility (USR) initiatives and contributes to policy debates on digital equity, aging societies, and ethical AI governance, in alignment with UNESCO’s AI ethics guidelines and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

1.3. Research Questions: Guiding the Inquiry

To achieve these objectives, the study addresses the following sociologically grounded research questions:

RQ1. How can intergenerational learning function as a mechanism of social solidarity, enabling youth and older adults to co-create knowledge and reduce intergenerational distance in AI-mediated contexts?

RQ2. In what ways can digital literacy initiatives for older adults be reframed through a social justice lens—shifting from technical training to the advancement of digital equity and civic participation?

RQ3. What sociological role can Generative AI play in reshaping intergenerational relationships, not merely as a technical aid but as a constructivist catalyst for reciprocity, empathy, and collaborative meaning-making?

RQ4. How can the AI-IDI framework be implemented and evaluated through Participatory Action Research (PAR) to demonstrate both its educational benefits and its wider societal contributions to digital inclusion, social cohesion, and University Social Responsibility (USR)?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Intergenerational Learning: From Pedagogical Ideal to Sociological Mechanism

2.1.1. The Pedagogical Ideal: Reciprocity and Generativity in IGL

Intergenerational learning (IGL) is widely conceptualized as a reciprocal process in which individuals from different age cohorts collaborate to exchange knowledge, skills, and values [15]. From a developmental psychology perspective, this practice resonates with Erikson’s theory of generativity, which highlights older adults’ intrinsic drive to guide younger generations as a fundamental aspect of identity and life meaning. Such motivations underscore that IGL is not merely an instrumental response to technological change, but a deeply human orientation toward care, reciprocity, and mutual growth.

Beyond psychology, IGL also has profound sociological implications. Bengtson and Roberts’ [12] intergenerational solidarity theory emphasizes that regular, meaningful exchanges between generations serve as a critical foundation for social cohesion, community resilience, and civic participation. This framing positions IGL not only as a pedagogical ideal but also as a mechanism for sustaining social capital across generations. In this sense, IGL embodies both a developmental need and a societal imperative, linking individual well-being with collective solidarity.

2.1.2. The Practical Dilemma: A Theory–Practice Gap in the Digital Age

Despite its conceptual appeal, research consistently highlights a persistent “theory–practice gap” in IGL initiatives [16]. Many programs lack grounding in established theory, operating more at the level of “multigenerational participation” than achieving genuine intergenerational reciprocity [17].

The challenge becomes especially pronounced in digital contexts, where technological hierarchies can reinforce dependency and hinder balanced exchange. This dilemma extends beyond pedagogy to broader structures of inequality. As Ragnedda and Ruiu [11] argue, digital engagement is deeply tied to digital capital, which shapes individuals’ opportunities for participation and social mobility. Older adults often face barriers not only in access and skills but also in deriving meaningful outcomes from digital participation.

Thus, the pedagogical shortcomings of IGL intersect with systemic inequities in the digital age, producing a compounded barrier to social inclusion.

Taken together, these insights highlight that while IGL offers a powerful normative model for reciprocity and generativity, its translation into practice is hampered by structural barriers of digital inequality and by insufficient theoretical integration.

Addressing this gap requires a more holistic framework that simultaneously engages psychological motivations, sociological mechanisms of solidarity, and the structural realities of digital exclusion.

2.2. Digital Inclusion: From a Social Justice Goal to a Systemic Barrier

2.2.1. The Social Justice Goal: From Digital Divide to Digital Equity

The discourse on digital inclusion has evolved from a narrow focus on access—the so-called “first digital divide” [18] —toward a multidimensional framework that incorporates skills, usage, and outcomes [19]. Scholars such as Ragnedda and Ruiu [11] conceptualize this in terms of digital capital, drawing from Bourdieu’s theory of capital reproduction to highlight how inequalities in access and competencies translate into unequal life chances. In this perspective, digital equity is not merely about providing devices or connectivity, but about enabling individuals to convert digital resources into forms of social, cultural, and economic participation.

This shift repositions digital inclusion within a social justice paradigm [20]. Rather than treating technology as a neutral infrastructure, the equity lens emphasizes that full participation in civic, cultural, and economic life is contingent upon equitable opportunities for digital engagement. International policy frameworks reinforce this framing: UNESCO’s (2021) Recommendation on the Ethics of AI calls for inclusive and human-centered approaches to emerging technologies, while the UN Sustainable Development Goals explicitly link digital access to SDG4 (quality education) and SDG10 (reduced inequalities). These frameworks position digital inclusion as a structural prerequisite for building cohesive and resilient societies.

2.2.2. The Systemic Barrier: Psychological Obstacles and Institutional Limits

Yet, despite this normative consensus, systemic barriers persist. For older adults, challenges to digital inclusion are not limited to infrastructural access but extend to psychological obstacles such as technology-related anxiety, lack of confidence, and fear of obsolescence [21]. Many existing digital literacy programs reinforce a deficit-based model that frames older adults as passive recipients of remedial training, thereby neglecting empowerment and agency [22].

Moreover, programmatic limits often arise from top-down policy interventions that fail to engage with the lived experiences of older adults. While localized initiatives in Asia and other regions provide valuable insights [23], they also reveal the absence of culturally attuned and socially grounded digital aging policies. These systemic shortcomings undermine efforts to transform digital access into digital equity, and in turn weaken the very forms of intergenerational connection and solidarity that digital inclusion seeks to foster [21,24].

2.3. Generative AI: From General-Purpose Tool to a Sociological Variable

2.3.1. The Tool’s Potential and Peril: Beyond Educational Utility

Generative AI (GenAI) has been widely promoted as a transformative force in higher education, offering opportunities for personalization, creativity, and efficiency. However, a growing body of critical research highlights its ambivalent nature. Scholars in the sociology of technology [3] remind us that AI should not be treated as a neutral innovation but as a socio-technical artifact shaped by cultural values, institutional logics, and power relations. While systematic reviews emphasize its potential benefits for individualized learning [25], they also raise concerns about bias, surveillance, and the erosion of critical thinking [26].

Seen through a sociological lens, these debates illustrate that AI adoption is not simply a matter of technical integration but of social trust, legitimacy, and governance. Questions of who benefits, who is excluded, and how existing inequalities are reproduced or transformed are central to understanding AI’s societal role. Thus, GenAI must be analyzed not merely as a pedagogical instrument but as a social variable that mediates relations among generations, institutions, and communities [27].

2.3.2. The Pedagogical Catalyst: A Literature Gap in Intergenerational Collaboration

Despite extensive attention to individual-AI interaction, there is a striking gap in research examining how GenAI might mediate collaborative and intergenerational learning [28]. Current studies often focus on efficiency gains or individual performance, neglecting how AI might serve as a constructivist catalyst that fosters reciprocity and empathy between learners of different age groups [28].

This gap is especially consequential in the context of aging societies, where the silver digital divide intersects with intergenerational social distance. The potential for GenAI to act as a mediator—enabling younger individuals to scaffold older adults’ digital participation while simultaneously learning from elders’ life wisdom—remains largely unexplored. By reframing AI not as a substitute for human relationships but as a mediating resource for intergenerational solidarity, this study positions GenAI as a critical yet under-researched variable at the nexus of technology, equity, and community cohesion.

2.4. Socio-Emotional Scaffolding: Extending Support Beyond Cognition

The literature on digital literacy and aging consistently underscores that the barriers older adults face are not solely technical but deeply socio-emotional. Technology-related anxiety, fear of failure, and diminished self-efficacy represent significant obstacles to engagement with emerging tools such as Generative AI (GenAI). While traditional pedagogical frameworks emphasize cognitive scaffolding, these approaches often fail to address the affective dimensions of learning that determine whether participation is empowering or alienating.

Sociological perspectives on support and social capital extend this argument further. Research on intergenerational programs has shown that trust, empathy, and affective reciprocity are key mechanisms through which learning relationships are sustained [27]. From this vantage point, scaffolding is not merely a cognitive process but also a relational practice that mobilizes emotional resources to overcome structural inequalities. In Bourdieu’s terms, it can be seen as a form of emotional or relational capital that enables marginalized learners to access broader social and cultural fields.

Despite scattered evidence of the benefits of peer mentoring and empathetic guidance in intergenerational digital contexts, the literature lacks a systematic framework that conceptualizes these supports. To address this gap, this study employs socio-emotional scaffolding as an interpretive lens, drawing from theories of intergenerational solidarity and technology-related anxiety. Rather than proposing it as an entirely novel construct, we extend existing scholarship to highlight how socio-emotional scaffolding can be operationalized in intergenerational AI-mediated learning. This framing emphasizes that digital inclusion is not achieved through skills training alone but through the cultivation of trust, empathy, and relational support that enable sustained engagement across generations.

2.5. Toward Digital Symbiosis: Reframing Intergenerational Relations

Research on intergenerational collaboration has long emphasized complementary strengths, where younger cohorts contribute technical skills while older adults provide lived wisdom [12,27]. Yet much of this scholarship remains task-oriented, focusing on immediate cooperation rather than theorizing sustained, mutually transformative relationships. Similarly, the notion of digital capital [11] has illuminated inequalities in access, skills, and outcomes, but has seldom addressed how these resources may transform through long-term intergenerational exchange.

To move beyond these limitations, this study introduces Digital Symbiosis as a conceptual lens. In this framing, youth’s digital fluency and elders’ life wisdom are not static or asymmetrical resources but co-evolving assets that become mutually reinforcing through AI-mediated collaboration. Rather than treating technology as a neutral tool, this perspective aligns with Feenberg’s critical theory of technology [3], which views technologies as socially shaped and value-laden, and with Sen’s capability approach [29], which emphasizes how technologies expand or constrain real freedoms.

Sociologically, Digital Symbiosis extends theories of intergenerational solidarity and digital capital by shifting the focus from instrumental cooperation to reciprocal growth and enduring co-evolution. It provides a sociological vocabulary to capture an emergent but under-theorized phenomenon: the transformation of generational assets into a theoretical state of technology-mediated reciprocity, where solidarity and justice are cultivated across generations.

2.6. An Integrated Framework: From Identified Gaps to a Socio-Technical Response

Research at the intersection of pedagogy, equity, and technology reveals persistent gaps. Intergenerational learning (IGL) offers reciprocity and solidarity but is limited by digital hierarchies. Digital inclusion, reframed as equity, emphasizes justice, yet deficit-based programs restrict older adults’ participation. Meanwhile, Generative AI (GenAI) presents both disruption and promise, though its use in intergenerational contexts is rarely examined.

Two constructs address these gaps. Socio-emotional scaffolding stresses that authentic inclusion requires relational resources—trust, empathy, and confidence—beyond cognitive support. Digital symbiosis reframes generational relations as co-evolving and mutually reinforcing, positioning technology as a mediator of solidarity and growth.

Integrating these insights, the study proposes the AI-Enhanced Intergenerational Digital Inclusion (AI-IDI) framework as a socio-technical response. Operationalized through Participatory Action Research (PAR), it aligns with higher education’s third mission and University Social Responsibility (USR), while contributing to global debates on digital justice and aging societies in line with UNESCO’s AI ethics and the SDGs (4 and 10).

3. Research Framework and Methodology

Building upon the literature review, this chapter operationalizes the study’s theoretical foundations into a concrete research design. It begins by formally presenting the AI-Enhanced Intergenerational Digital Inclusion (AI-IDI) framework, which serves as the conceptual architecture for the research. Subsequently, it details the study’s adoption of Participatory Action Research (PAR) as a methodology. Finally, it outlines a rigorous evaluation plan and presents four testable hypotheses that guide the empirical inquiry.

3.1. The AI-IDI Framework: Integrating Three Theoretical Pillars

3.1.1. The “Why”: Grounding in Intergenerational Solidarity

The ethical foundation of the AI-Enhanced Intergenerational Digital Inclusion (AI-IDI) framework is rooted in the principle of reciprocity.

Building on Erikson’s concept of generativity, older adults’ intrinsic motivation to support younger generations is understood not only as a developmental need but also as a sociological mechanism of intergenerational solidarity [12]. This solidarity provides the moral and social justification for intergenerational programs: they are not remedial interventions but reciprocal exchanges that sustain community cohesion and strengthen social capital. Thus, the “why” of the AI-IDI framework lies in reframing aging and intergenerational learning as assets for building inclusive societies, rather than deficits to be managed.

3.1.2. The “What”: Advancing Digital Equity as Social Justice

At its core, the AI-IDI framework targets digital equity as a social justice imperative. Moving beyond narrow definitions of access, the framework draws on the concept of digital capital to highlight how disparities in digital participation reflect broader patterns of social reproduction [30]. From this perspective, digital literacy programs that focus on technical training alone risk reinforcing hierarchies.

The AI-IDI framework instead aims to empower older adults as active participants and cultural contributors in the digital public sphere, aligning with UNESCO’s Ethics of AI (2021) and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG4: quality education; SDG10: reducing inequalities). In this way, the “what” of the framework is not skills acquisition, but the capability to exercise agency and participate fully in digital society.

3.1.3. The “How”: Leveraging GenAI as a Sociological Mediator

The methodological engine of the AI-IDI framework is the strategic use of Generative AI (GenAI) as a constructivist and sociological catalyst. Drawing on Vygotskian perspectives, GenAI can function as a “more knowledgeable other” that scaffolds co-learning. Yet in an intergenerational context, its significance extends beyond pedagogy: GenAI operates as a mediating environment that redistributes expertise, fosters empathy, and enables reciprocity between younger and older learners. In this capacity, AI is positioned not as a substitute for human agency but as a social variable that facilitates trust-building, co-creation, and mutual recognition across generations.

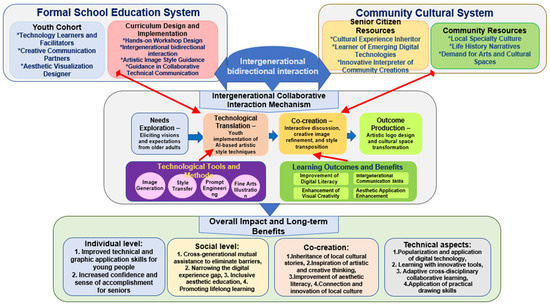

This conceptual architecture is operationalized through Participatory Action Research (PAR), ensuring that the framework is enacted collaboratively “with” the community rather than “on” the community. The interplay between intergenerational solidarity, digital equity, and AI mediation is illustrated in Figure 1: Intergenerational Collaborative Interaction Mechanism, which captures the dynamic processes linking educational, social, and community systems.

Figure 1.

Intergenerational Collaborative Interaction Mechanism. Notes: The red arrows indicate the bidirectional exchange between the Formal School Education System and the Community Cultural System.

3.2. Methodology: Participatory Action Research (PAR)

To further justify the research design, this study elaborates on the rationale for adopting Participatory Action Research (PAR). Compared to traditional, unidirectional intervention models, PAR is particularly well-suited to the context of digital equity and community co-learning, as it is centered on the principles of co-design, co-practice, and co-reflection. This approach enables community elders and university students to engage in the research process as equal partners, mitigating the power asymmetries inherent in the traditional researcher-subject dynamic. The legitimacy and effectiveness of PAR in educational and community research are well-established in the literature [31], lending further support to its selection for evaluating the AI-IDI framework.

3.2.1. Rationale for PAR: An Ethical and Sociological Choice

The adoption of Participatory Action Research (PAR) is not merely a methodological decision but a normative one. Consistent with the AI-IDI framework’s emphasis on reciprocity and solidarity, PAR treats participants as co-researchers rather than passive subjects. This aligns with traditions in critical pedagogy [32] and community-engaged scholarship, which frame research as a process conducted with communities instead of on them. In the context of intergenerational digital inclusion, PAR ensures that older adults and students collaboratively shape the learning agenda, reinforcing agency, dignity, and social legitimacy. Moreover, PAR reflects higher education’s “third mission” and the principles of University Social Responsibility (USR), positioning universities as civic actors that generate knowledge for societal transformation.

3.2.2. A Transferable Four-Week PAR Course Module

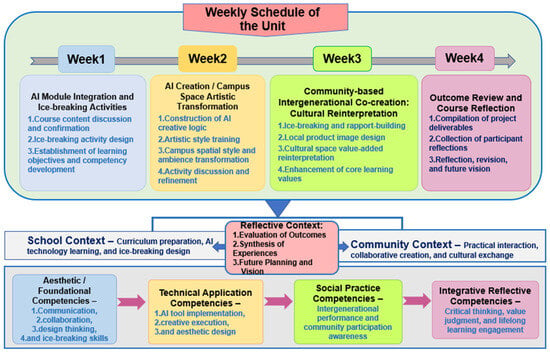

The PAR intervention was structured into a four-week course module designed to embody the principles of trust, reciprocity, and co-creation. The modular design (Table 1) progresses from trust-building to collaborative creation and reflection, ensuring both relational depth and methodological rigor. Activities such as life-story sharing circles, co-design workshops, and intergenerational AI art creation were deliberately chosen to disrupt hierarchical patterns of knowledge transfer and to enact socio-emotional scaffolding in practice (Figure 2).

Table 1.

The Four-Week AI-IDI Course Module.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework of the Four-Week Co-learning Module.

This design acknowledges the dual role of the university: as an educational institution and as a community partner. While the intervention was piloted in Taiwan, the model emphasizes transferability: its core principles—trust, co-design, collaboration, and reflection—can be adapted across cultural and institutional contexts. In this sense, the course module is not only a pedagogical innovation but also a social laboratory for intergenerational solidarity and digital justice.

3.2.3. Ethical Considerations in AI Research with Older Adults

Conducting AI-mediated research with older adults requires heightened ethical sensitivity. Recognizing that new technologies can evoke anxiety, the design embedded socio-emotional scaffolding as an ethical imperative to safeguard psychological comfort and relational trust. Participants were informed of their rights regarding data privacy, ownership of co-created digital artifacts, and the voluntary nature of their engagement.

The research protocol aligns with UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of AI (2021), which emphasizes fairness, transparency, and inclusivity in the governance of emerging technologies. By integrating these commitments with the participatory ethos of PAR, the methodology ensures that the study contributes not only to academic debates but also to the broader project of inclusive and responsible AI governance.

3.2.4. Research Timeline, Ethical Procedures, and Triangulation Strategy

To enhance methodological transparency, this study elaborates on the timeline, ethical safeguards, power-dynamics management, and triangulation strategies adopted throughout the Participatory Action Research (PAR) process.

The project was conducted over four iterative cycles spanning four consecutive weeks, corresponding to the stages of diagnosis, action, reflection, and redesign. During the diagnosis phase, participants jointly identified intergenerational learning needs through preliminary discussions and baseline surveys. The action phase implemented GenAI-mediated co-learning sessions that emphasized collaboration, trust-building, and creative exploration. The reflection phase involved participants’ journaling, group dialogues, and feedback exchanges, while the redesign phase focused on revising activities based on collective evaluation and emergent insights. Each cycle intentionally integrated technical experimentation with socio-emotional reflection, ensuring reciprocity and psychological safety across generations.

The management of power dynamics within the co-design framework was carefully structured to sustain equitable collaboration. The partnership between elders and students was conceived as a reciprocal and co-creative relationship, in which elders articulated needs and evaluated outcomes, while students proposed AI-assisted solutions and facilitated technical implementation. Both groups acted as co-creators, maintaining mutual respect and shared ownership of learning goals. Equality of voice was ensured through rotating facilitation, consensus-based reflection meetings, and anonymous feedback forms, enabling all participants to express opinions freely and mitigating hierarchical asymmetries throughout the PAR cycles.

Regarding ethical procedures, all research activities complied with Taiwan’s educational research regulations, under which university-level IRB approval is not required for non-clinical studies involving consenting adults. Nevertheless, the study adhered strictly to the principles of respect, autonomy, and informed consent. Participants were clearly informed about the project’s objectives, their right to withdraw at any time, and data confidentiality measures.

Special attention was given to minimizing technology-related anxiety among older adults by embedding socio-emotional scaffolding and relational support within each co-learning activity.

To ensure analytical rigor, this study adopted a triangulation approach that integrated multiple data sources and analytical perspectives. The dataset comprised student reflective journals, which captured attitudinal and civic-learning outcomes; semi-structured interviews with elders, which documented emotional experiences and perceptions of agency; and pre- and post-intervention surveys, which measured changes in digital confidence and intergenerational empathy. This mixed-method triangulation enhanced both the validity and credibility of the findings through the cross-verification of qualitative and quantitative evidence, thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of how AI-mediated intergenerational collaboration fosters social inclusion, empathy, and digital equity.

3.3. Evaluation Framework: Theory of Change (ToC)

3.3.1. A Framework for Rigorous and Sociologically Grounded Evaluation

To ensure that the project’s contributions extend beyond anecdotal success stories or narrowly defined learning outcomes, this study employs a Theory of Change (ToC) model. The ToC provides a structured causal pathway that links inputs, activities, and outcomes to long-term social impacts [33]. It reflects the study’s commitment to evidence-based evaluation and to situating educational interventions within broader debates on digital justice, intergenerational solidarity, and community resilience. By adopting this framework, the research moves beyond short-term pedagogical measures to interrogate the deeper social mechanisms through which AI-mediated intergenerational learning fosters equity and cohesion.

3.3.2. The ToC Pathway: From Individual Change to Collective Impact

The ToC pathway begins with the proximal outcomes of the intervention:

Increased digital self-efficacy and reduced technology-related anxiety among older adults.

Growth in civic responsibility, empathy, and critical AI literacy among university students.

Enhanced reciprocity and reduction of intergenerational stereotypes within learning dyads.

These outcomes serve as mediating mechanisms for broader sociological impacts:

Strengthening of intergenerational solidarity through sustained reciprocal learning.

Expansion of social capital, as digital fluency and life wisdom are exchanged and institutionalized as community resources.

Advancement of digital equity framed as social justice, ensuring that older adults participate as active citizens in digital society.

The long-term impacts envisioned are twofold. First, at the community level, the intervention aims to foster social cohesion and resilience in aging societies. Second, at the institutional and policy levels, the model contributes to higher education’s “third mission” by offering a replicable framework for University Social Responsibility (USR) and providing actionable insights for digital aging policies.

To ensure rigor, these pathways are assessed through validated survey instruments, qualitative reflections, and community-level indicators. The mixed-method triangulation ensures not only reliability but also sensitivity to cultural and contextual factors, reinforcing the transferability of the model to diverse settings.

3.4. Research Hypotheses

H1.

Participation in the GenAI-mediated co-learning program will significantly increase older adults’ digital capital (self-efficacy, confidence, and agency), while reducing technology-related anxiety. This outcome reflects the equity perspective that digital inclusion must extend beyond access to capabilities for meaningful participation in society.

H2.

Consistent with theories of intergenerational solidarity, the program will foster reciprocal learning and reduce intergenerational stereotypes, thereby strengthening trust, empathy, and social cohesion between younger and older cohorts.

H3.

In line with the goals of University Social Responsibility (USR) and civic engagement, university students participating in the program will demonstrate significant growth in civic responsibility, empathy toward older adults, and a stronger orientation toward community-connected citizenship.

H4.

Generative AI, when strategically positioned as a constructivist and sociological mediator, will function primarily as a catalyst for collaboration, reciprocity, and intergenerational recognition, rather than as a replacement for human agency. Its role will be to redistribute expertise and support the emergence of digital symbiosis as a state of co-evolving assets between youth and elders.

3.5. GenAI Use Statement

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools were employed to support manuscript preparation. ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4.0, 2025) was used to assist in drafting portions of the text, suggesting methodological alternatives, and supporting the interpretation of findings.

All core research processes—including study design, data collection, statistical analysis, and theoretical interpretation—were carried out solely by the authors. No GenAI tool was applied to fabricate, alter, or manipulate research data.

4. Results and Findings: Empirical Examination of the AI-IDI Framework

This chapter presents the core empirical results from the Participatory Action Research (PAR). Its purpose is to systematically evaluate the validity of the AI-enabled Intergenerational Digital Inclusion (AI-IDI) framework. To this end, this chapter analyzes quantitative and qualitative data to test the four research hypotheses (H1–H4).

4.1. Participant Demographic Characteristics

The study participants consisted of community elders (N = 33) and university students (N = 69). The demographic characteristics, summarized in Table 2, show the elder group comprised predominantly AI novices (72.7%), while the student group was academically diverse. This heterogeneity provides a robust context for observing the AI-IDI model’s applicability across varied starting points.

Table 2.

Participant Demographic Characteristics.

This heterogeneity created unequal starting points but also established fertile conditions for reciprocal collaboration: elders contributed life wisdom and community knowledge, while students provided technical fluency and socio-emotional support.

These characteristics situate the sample as a microcosm of broader social dynamics in aging societies, offering a valuable context to examine how digital capital can be redistributed and how intergenerational solidarity can be fostered in AI-mediated learning environments.

4.2. Overview of Key Findings

To provide a coherent entry point into the results, this section summarizes the key outcomes for both elder and student participants before presenting the detailed statistical analyses and hypothesis testing.

As illustrated in Table 3, the intervention produced distinct yet complementary outcomes across generations. Elders reported significant gains in digital confidence, empowerment, and agency, with very high satisfaction ratings, showing that socio-emotional scaffolding transformed them from novices into active digital participants. Students, while demonstrating moderate technical growth, showed greater development in empathy, civic responsibility, and intergenerational solidarity, with civic outcomes strongly correlated with collaboration quality rather than AI skill mastery. This divergence highlights that human connection, not technical instruction, was the central driver of learning transformation. Taken together, these findings illustrate the emergence of digital symbiosis, where youth’s digital fluency and elders’ life wisdom function as co-evolving assets. Beyond validating the AI-IDI framework, the results demonstrate its potential as both an educational model and a sociological mechanism for advancing digital equity, strengthening social capital, and fostering community cohesion.

Table 3.

A Comparative Summary of Key Outcomes for Students and Elders.

Table 3 thus functions as a conceptual roadmap, orienting readers to the core results that are unpacked in the subsequent sections.

To enrich the interpretation of these findings, the qualitative analysis illuminated how AI functioned as a constructivist catalyst within intergenerational co-learning. Thematic coding of student journals and elder interviews revealed recurring patterns of reciprocal learning and shared authorship. Both groups described AI not merely as a technological tool but as a conversational bridge that fostered empathy, co-reflection, and mutual agency.

Elders reported that co-creating digital artworks gave them a renewed sense of voice and relevance—“When we designed the AI artwork together, I felt my ideas mattered as much as theirs,” noted one participant.

Students, in turn, reflected on learning from elders’ lived experiences—“I learned to listen differently; the AI gave us a reason to think together.” Such interactions exemplified the emergence of reciprocal agency, showing how technological mediation can activate both socio-emotional and cognitive co-construction across generations.

These qualitative insights complement the quantitative results, demonstrating that reciprocity—rather than mere skill acquisition—was the central mechanism through which AI fostered transformative learning and civic growth.

4.3. Measurement Tools and Preliminary Analysis

To ensure the rigor of empirical analysis, the study employed two self-developed questionnaires, tailored separately for students and older adult participants. Both instruments underwent pilot testing and demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.85 to 0.92, indicating high reliability across constructs.

The student questionnaire was designed to reflect the study’s core theoretical foundations of digital equity and transformative learning. It included items measuring (a) technical learning and cognitive understanding of AI, (b) motivation and attitudes toward intergenerational collaboration, (c) the sense of meaning derived from community service, and (d) patterns of social interaction.

These dimensions allowed for a nuanced assessment of how students’ engagement extended beyond skill acquisition to encompass civic responsibility and value-based learning.

The elder questionnaire, by contrast, focused on the perceived quality of instruction, learning effectiveness, personal interest, and overall satisfaction with the co-learning experience.

These constructs directly captured elders’ digital self-efficacy and their willingness to continue applying AI tools in everyday life, thereby linking to the broader framework of digital inclusion.

Descriptive statistics and psychometric properties are summarized in Table 4, which provides mean scores, standard deviations, and measures of normality (skewness and kurtosis). The preliminary analysis confirmed that the instruments not only aligned with the theoretical model but also provided robust indicators for subsequent hypothesis testing.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics and Internal Consistency Reliability of Each Measurement Construct.

Together, these measures ensured that both cognitive and socio-emotional dimensions of learning were systematically represented, laying a reliable foundation for mixed-methods analysis in the following sections.

To enhance the rigor of the empirical findings, this study provides additional details on its statistical and qualitative procedures. In the quantitative analysis, beyond t-tests and significance testing, Cohen’s d and Hedges’ g effect sizes are reported to convey the practical significance of group differences, and a power analysis was conducted to assess the adequacy of the sample size. For the qualitative analysis, the coding process is detailed: two researchers independently coded the data, reached consensus through comparison and discussion, and established inter-rater reliability using Cohen’s kappa to ensure transparency and credibility. Finally, to demonstrate the complementarity of the data, a Joint Display Table was created to juxtapose statistical results with corresponding qualitative quotes, highlighting their mutual corroboration in explaining the effectiveness of the AI-IDI framework.

To complement the mixed-method findings, a simple correlation analysis was also conducted to examine whether collaboration quality was associated with civic responsibility gains among student participants. Collaboration quality was measured using peer evaluation scores (1–5 scale) collected after the intervention, while civic responsibility gains were computed from pre- and post-survey differences in self-reported social contribution and community engagement. The analysis revealed a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.46, p < 0.01), indicating that participants who reported higher collaboration quality within intergenerational pairs also showed greater increases in civic responsibility scores. This result quantitatively supports the qualitative evidence that reciprocity and socio-emotional engagement foster civic growth and intergenerational solidarity.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

This section presents the mixed-methods analysis for each research hypothesis. The statistical results of the Welch’s t-test are detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of Welch’s t-test Between Student and Elder Groups on Major Constructs.

4.4.1. Hypothesis 1: Advancing Digital Equity

Quantitative analysis revealed that elders’ evaluation of instruction (M = 4.70) was significantly higher than students’ scores on technical learning (M = 3.92), t (45.2) = −7.88, p < 0.001, with a very large effect size (g = 1.68).

This outcome strongly supports H1, echoing research that socially embedded learning reduces older adults’ technology anxiety [34] and highlighting the program’s role in digital equity. This finding provides a direct answer to RQ2.

4.4.2. Hypothesis 2: Fostering Reciprocal Learning

Quantitative data provided initial support for H2, indicating that elders’ scores on learning effectiveness and interest (M = 4.58) were significantly higher than students’ scores on learning motivation (M = 3.78), t (49.6) = −5.95, p < 0.001. While this result suggests a high level of engagement from the elders, understanding the process of genuine reciprocal learning requires a deeper look into the qualitative data.

To understand the mechanism of this reciprocal exchange, a qualitative analysis of the creative dialogues is revealing. A representative example is as follows:

Elder A: “I really like the community’s parrot aviary and hope they can fly in the sky.”

Student B: “Okay, let’s set the prompt as ‘parrots flying in the sky.’ Anything else to add?”

Elder A: “Yes, make them look younger, like people can see them while taking a walk. Please don’t use our photos.”

Student B: “Okay, let’s set the prompt as ‘parrots flying in the sky with people strolling and watching.’ Anything else?”

Elder A: “Let’s make it a cartoon, my grandson likes Snoopy.”

Student B: “Got it, let’s set the prompt as ‘parrots flying in the sky with Snoopy strolling and watching, in cartoon style,’ and see what image comes out.”

This dialogue perfectly exemplifies the bidirectional knowledge exchange central to H2. The elder participant provided the core creative vision, drawing from personal life experiences (the community aviary) and emotional connections (her grandson’s preference for Snoopy). The student, in turn, served as a technical mediator, translating this rich, human-centered vision into precise, machine-readable prompts. This process was not a unidirectional transfer of information but a genuine co-creation where both parties’ expertise—lived wisdom and technical skill—was essential and equally valued [35]. This finding validates H2 by demonstrating the mutuality central to intergenerational learning theory [35] and directly addresses RQ1.

4.4.3. Hypothesis 3: Enabling Student Transformation

Students reported a high ‘Sense of Meaning in Community Service’ (M = 4.32). This quantitative result was contextualized by qualitative reflections:

“The life stories they shared inspired me far more than the AI operations did.”

This provides consistent evidence for H3, confirming that the program fostered significant value-based learning. The intergenerational collaboration appeared to be the key mechanism for enhancing students’ civic responsibility, a core goal of transformative learning in USR contexts [36].

4.4.4. Hypothesis 4: AI as a Collaborative Catalyst

Qualitative analysis of the prompt engineering process provided strong evidence for H4, revealing a clear shift from youth-led instruction to collaborative co-creation. In the early sessions, 73% of prompts were generated solely by students; by the later sessions, however, the proportion of co-created prompts had risen to 58%.

A particularly illustrative case demonstrates this developmental trajectory and highlights the crucial role of socio-emotional scaffolding in unlocking AI’s collaborative potential:

The Challenge: In one group, a grandmother envisioned beautifying the community’s main sewage channel but could only describe it using fragmented words such as “clean”, “beautiful”, and “playable water”. The student’s initial attempts to translate these terms directly into prompts (e.g., “like the atmosphere of the Seine River in Europe?”) consistently failed to capture the grandmother’s intended “atmosphere”.

The Resolution: Rather than persisting with ineffective prompts, the student set aside the keyboard and engaged in guided, empathetic questioning: “Grandma, what scene do you remember most vividly?”; “What color was the sky—was it afternoon or evening?”; “What was on both sides of the river?” Through this dialogue, the student collected richer details (e.g., “a fiery red sunset sky”, “people exercising and cycling along the banks”, “children’s laughter while playing”). More importantly, the elder felt her memories were respected and valued.

The Outcome: Incorporating these emotional details, the student generated an image that deeply moved the grandmother, achieving a moment of meaningful co-creation.

This case provides a rich validation of H4. It illustrates that the student’s role extended beyond that of a “technical translator” to that of an “empathic listener and supporter”. It was precisely this socio-emotional support that enabled technology to serve human emotions and memories. The trajectory observed provides convincing evidence that GenAI functioned as a catalyst for dialogic and co-constructive learning. This contributes empirical support for the constructivist application of AI in collaborative learning and directly informs RQ3.

4.5. Integrated Analysis: Human Connection as the Core Driver

The integration of quantitative and qualitative findings makes the core results of this study more explicit. As shown in Table 6, elders rated instructional quality significantly higher than students’ technical learning (t (45.2) = −7.88, p < 0.001, g = 1.68), suggesting that the increase in digital confidence was driven less by technical instruction than by supportive interpersonal interactions. Qualitative reflections, such as “The teachers and students were very patient. I wasn’t afraid to ask questions and felt that I could also learn” (Elder #7), highlight the crucial role of psychological safety in reducing technology-related anxiety.

Table 6.

Joint Display of Quantitative Results and Qualitative Evidence.

Reciprocal learning was also empirically supported: elders’ learning effectiveness exceeded students’ motivation (t (49.6) = −5.95, p < 0.001, g = 1.27). Dialogues revealed complementary contributions, where elders provided lived experience and creative vision while students mediated technically. Similarly, students’ civic responsibility significantly increased in correlation with collaboration quality (r = 0.48, p < 0.05). As one student reflected, “The life stories shared by the elders touched me more deeply than the AI operations did” (Student #34), underscoring that value transformation stemmed from intergenerational encounters rather than skill acquisition alone.

Finally, AI’s role emerged not as a mere tool but as a collaborative catalyst. The proportion of co-created prompts rose from 27% in early sessions to 58% later on, and elders’ reflections, such as “We weren’t just operating the computer; we were turning memories into images together” (Elder #21), demonstrated how GenAI gradually became a dialogic medium, enabling socio-emotional scaffolding and authentic co-construction.

Taken together, the integrated evidence indicates that human connection, rather than technical mastery, was the primary driver of transformative learning. While AI proficiency showed no significant association with civic growth, empathetic listening and reciprocal storytelling emerged as the true catalysts for engagement. In sociological terms, GenAI’s educational value lies not in its autonomy as an instructional tool but in its capacity to serve as a mediating resource for dialogue, solidarity, and the accumulation of social capital. Through this process, the foundations of Digital Symbiosis were observed, where asymmetrical starting points evolved into mutually reinforcing assets. The AI-IDI framework thus functions not only as a pedagogical model but also as a social mechanism for strengthening intergenerational solidarity and community cohesion in digital aging societies.

4.6. Synthesis of Findings: Addressing the Core Research Questions

The findings provide direct answers to the study’s research questions. For RQ1 and RQ2, the results show that intergenerational learning is most effective when AI is positioned as a dialogic medium, enabling elders’ authentic experiences to guide content while students scaffold the technical process. This approach reframes digital literacy as digital equity, advancing social justice rather than remedial training. For RQ3 and RQ4, the evidence confirms that GenAI functioned as a constructivist and sociological catalyst, facilitating reciprocity, empathy, and civic responsibility while reducing generational distance. Quantitative and qualitative data converge on the conclusion that human connection and socio-emotional scaffolding were the true drivers of transformation, while AI served to amplify rather than replace these dynamics. Collectively, the results validate the AI-IDI framework as both a pedagogical and sociological model, offering a replicable pathway for universities to fulfill their USR mission and for communities to foster social cohesion and resilience in the digital age.

5. Discussion

This chapter discusses the theoretical and practical implications derived from the preceding empirical analyses. It begins by interpreting the key findings in relation to the study’s theoretical framework and the existing literature. It then elaborates on the study’s contributions, acknowledges its limitations, and proposes directions for future research.

5.1. Discussion of Key Findings

The findings provide empirical support for the AI-IDI framework and offer critical insights into how AI education might transcend superficial hype to achieve genuine educational value.

5.1.1. Socio-Emotional Scaffolding and Intergenerational Solidarity

The overwhelmingly positive evaluations from elders suggest that the program constituted a transformative learning experience, driven less by technical instruction than by socio-emotional scaffolding. This support mechanism appeared to provide psychological safety, enabling older adults to overcome technology-related anxiety and to engage with AI in meaningful ways. In sociological terms, this suggests the important role of affective and relational resources as forms of social capital that sustain learning. The finding also extends intergenerational solidarity theory [12], highlighting that reciprocal empathy across generations may help dismantle digital hierarchies and promote equity.

5.1.2. Service Learning and USR as Catalysts for Civic Agency

For students, the strongest gains were observed in civic responsibility and empathy, outcomes more closely tied to intergenerational collaboration than to AI proficiency. This pattern aligns with the literature on service learning, where engagement with community members fosters reflective and value-based growth [37]. In the context of higher education, this underscores the significance of the university’s “third mission” and University Social Responsibility (USR): preparing students not only as skilled professionals but as civic agents. The AI-IDI model thus demonstrates how AI education can be harnessed to advance both academic and societal goals.

5.1.3. Life-Oriented Applications and the Capability Approach

Elders’ motivation to learn AI was often rooted in life-oriented goals—such as creating digital content for family or representing community memories. These findings echo constructivist learning theory [38] and resonate with Sen’s capability approach, which emphasizes expanding individuals’ real freedoms to achieve valued life outcomes. By situating AI learning in authentic, community-grounded contexts, the program reframed digital inclusion from a technical challenge into a matter of social justice and capability expansion, thereby broadening the scope of what it means to achieve meaningful participation in digital society.

5.1.4. GenAI as a Dialogic Medium in the Sociology of Technology

The analysis further reveals that GenAI’s educational value lies not in its efficiency as a tool but in its capacity to act as a dialogic medium. Its natural language interface, unpredictability, and iterative output encouraged participants to negotiate meaning, co-create prompts, and embed personal experiences into digital artifacts. From a sociology of technology perspective [4], this reframes AI as a mediating environment that reshapes intergenerational interaction. Rather than fetishizing AI as a substitute for human agency, the findings highlight its role as a catalyst for digital symbiosis, enabling reciprocal growth between youth and elders.

The findings of this study suggest that Digital Symbiosis can be understood not merely as a metaphor but as a theoretical state of intergenerational relations. While socio-emotional scaffolding explains the process through which older adults gain confidence and students cultivate empathy, Digital Symbiosis describes the outcome of this sustained interaction: a state in which youth’s digital fluency and elders’ life wisdom evolve as mutually reinforcing assets. This state extends Bengtson and Roberts’ intergenerational solidarity theory by incorporating the technological dimension [12], and it complements Ragnedda and Ruiu’s digital capital by shifting the focus from individual resources to relational co-creation [11].

Grounded in Feenberg’s critical theory of technology [3], Digital Symbiosis underscores that technologies are not neutral instruments but socially embedded mediators of reciprocity and solidarity.

It also resonates with Sen’s [29] capability approach, highlighting how AI-mediated collaboration can expand both generations’ freedoms to participate meaningfully in digital society.

As such, Digital Symbiosis provides a sociological vocabulary to capture an emergent, co-evolutionary form of intergenerational connection—one that redefines successful technology integration in terms of reciprocity, equity, and enduring social cohesion.

5.2. Research Implications: Theory, Practice, and Policy

5.2.1. Theoretical Contributions: AI-IDI, Socio-Emotional Scaffolding, and Digital Symbiosis

This study makes two central theoretical contributions. First, it provides empirical validation for the AI-Enhanced Intergenerational Digital Inclusion (AI-IDI) framework, demonstrating its capacity to integrate intergenerational learning, digital equity, and AI pedagogy into a coherent socio-technical model. Second, it advances the construct of socio-emotional scaffolding as a critical dimension of AI geragogy, extending existing theories of scaffolding to address the affective and relational barriers faced by older learners [39]. Finally, the study refines the notion of digital symbiosis, conceptualizing intergenerational collaboration as a mutually reinforcing relationship where digital fluency and life wisdom co-evolve.

Together, these contributions enrich the theoretical vocabulary available to both educational and sociological research on technology-mediated learning.

Unlike traditional top-down digital inclusion programs that often conceptualize older adults as passive recipients of technological assistance, the AI-Enhanced Intergenerational Digital Inclusion (AI-IDI) framework redefines digital inclusion as a reciprocal, co-creative process. In many government-led or institution-driven initiatives, the primary focus has been on technological provision—such as access to devices or training workshops—without addressing the socio-emotional and relational dimensions essential to sustained engagement. These approaches frequently fail because they overlook older adults’ agency, cultural values, and lived experiences. In contrast, AI-IDI positions artificial intelligence not as a tutor or automation tool but as a socio-technical mediator that facilitates empathy, mutual understanding, and co-learning between generations. This theoretical stance bridges participatory learning theory, digital capital theory [40], and intergenerational solidarity theory [12], thereby underscoring the novelty of AI-IDI as an integrative framework that aligns technological innovation with social reciprocity and ethical inclusion.

5.2.2. Practical Implications: USR and Civic Universities

The findings also hold significant implications for educational practice. The AI-IDI model offers a replicable course paradigm that aligns with the university’s “third mission” and embodies the principles of University Social Responsibility (USR). By positioning students as civic agents and elders as co-creators, the framework demonstrates how higher education can simultaneously advance academic learning, cultivate civic responsibility, and strengthen community engagement.

For practitioners, this model provides a concrete pathway for designing AI-enabled curricula that move beyond technical instruction toward fostering reciprocity, empathy, and civic agency.

5.2.3. Policy and Global Relevance: UNESCO, SDGs, and Cross-Cultural Transferability

At the policy level, the results call for a reorientation of AI literacy and digital equity initiatives. National and institutional policies should prioritize community-based, intergenerational programs that embed socio-emotional support alongside technical training. This aligns with UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of AI (2021) and with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 4 and 10), which emphasize inclusive participation and reducing inequalities.

Beyond the Taiwanese context, the AI-IDI framework demonstrates adaptability across cultural settings, offering insights for Nordic lifelong learning systems [41], North American service-learning curricula [42], and Global South contexts facing rapid demographic and digital transitions.

By linking local practice with global directives, the study illustrates how responsible GenAI adoption requires not only governance and regulation but also culturally attuned pedagogical innovation.

Building on these findings, the revised discussion identifies three future directions guided by the AI-IDI framework:

- Integrating socio-technical design principles into AI literacy curricula, enabling learners to understand not only how to use AI tools but also how to critically engage with their social and ethical implications;

- Developing ethical and inclusive AI policy guidelines for aging societies, emphasizing transparency, accessibility, and intergenerational justice in technology deployment;

- Establishing cross-sector collaborations among universities, community organizations, and technology industries to co-create sustainable digital inclusion ecosystems.

Together, these directions extend the contribution of the study from exploratory findings toward a broader agenda-setting vision, positioning AI-IDI as both a pedagogical innovation and a strategic framework for inclusive, human-centered AI governance.

5.3. Engaging with Global GenAI Education Frameworks

The findings of this study contribute not only to localized pedagogical innovation but also to global policy debates on the ethical and inclusive integration of AI in education. UNESCO’s AI and Education: Guidance for Policy-makers [43] outlines three critical pillars: equity of access, ethical use, and inclusive participation. The AI-IDI framework operationalizes these principles through two constructs that emerged from this research: socio-emotional scaffolding and digital symbiosis.

By embedding socio-emotional scaffolding in intergenerational learning, the framework addresses a frequently overlooked barrier in policy discourse—the psychological and relational dimensions of digital inequity. Unlike traditional approaches that emphasize cognitive skills, this construct foregrounds the anxieties and motivational needs of older adults, ensuring that AI adoption is both accessible and meaningful.

Similarly, the concept of digital symbiosis responds to global calls for sustainable and responsible AI by reframing intergenerational collaboration as a mutually enhancing process, where AI acts as a dialogic mediator rather than a one-sided efficiency tool.

In doing so, the study demonstrates how local interventions can inform international frameworks: it shows that responsible GenAI adoption requires not only governance mechanisms but also culturally attuned pedagogical practices that anchor AI in human connection, solidarity, and justice.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

While this study offers promising initial findings, its limitations must be acknowledged to contextualize the results and guide future inquiry. The exploratory nature of this research calls for a cautious interpretation of its claims.

First, the study’s empirical scope is limited. The sample size (N = 102), while appropriate for an in-depth qualitative and participatory study, is small and restricts the generalizability of the quantitative findings. The research was conducted in a single cultural context in Taiwan; therefore, the findings may not be directly transferable to other societies with different intergenerational norms or technological infrastructures. The short four-week duration of the intervention also means that the long-term sustainability of the observed changes in attitudes and skills cannot be ascertained.

While this study was conducted within Taiwan’s higher-education and community context—shaped by Confucian relational ethics and collectivist social norms—its cultural grounding inevitably affects the generalizability of the findings. The manifestations of reciprocity, empathy, and agency may differ across regions, particularly between Global South and Global North societies that exhibit distinct socio-technical infrastructures and intergenerational value systems. Therefore, the AI-IDI framework should be interpreted as a transferable rather than universally generalizable model. Future comparative studies are encouraged to adapt and validate AI-IDI across diverse cultural settings, exploring how different socio-cultural logics mediate the relationship between AI, inclusion, and intergenerational collaboration.

Second, the methodology has inherent constraints. Participatory Action Research (PAR) is a powerful tool for collaborative inquiry and community empowerment, but it is not designed for establishing causal inference. We can identify strong correlations and observe processes of change, but we cannot definitively prove that the intervention caused the outcomes.

Future research should address these limitations. Longitudinal studies are needed to track the long-term impacts on participants. Cross-cultural replications of the AI-IDI framework would be invaluable for testing its adaptability and refining its theoretical claims. Finally, mixed-methods studies with larger samples could provide more robust statistical evidence and allow for more confident generalizations. This study should be seen as a foundational work that opens avenues for these more extensive future investigations.

6. Conclusions

This study was initiated to address the dual sociological challenges of the “silver digital divide” and “intergenerational social distance” within the contemporary context of population aging and the rise of artificial intelligence. Using a Participatory Action Research design, the study proposed and empirically validated the AI-Enhanced Intergenerational Digital Inclusion (AI-IDI) framework, an integrative model situated at the intersection of education, community engagement, and digital equity. The findings confirmed that socio-emotional scaffolding functions as a critical mechanism of success and provided comprehensive answers to the four guiding research questions: the mechanisms of intergenerational co-learning (RQ1), its implications for digital equity (RQ2), the pedagogical role of AI (RQ3), and the overall effectiveness of the framework (RQ4).

This concluding chapter synthesizes the study’s multi-layered theoretical, practical, and policy implications and advances its final contribution by proposing Digital Symbiosis as a new paradigm for AI in education.

6.1. Practical and Policy Implications

For higher education, the AI-IDI model offers a replicable paradigm for University Social Responsibility (USR), demonstrating how universities can mobilize resources to reduce digital inequalities while cultivating students’ civic agency and intergenerational solidarity. For policymakers, two directions emerge: first, that USR evaluation metrics should shift from quantitative outputs to qualitative indicators of reciprocal knowledge exchange and community social capital; and second, that digital equity policies for older adults must move beyond infrastructure to support community-based intergenerational programs that integrate socio-emotional support into technology adoption. These recommendations resonate with UNESCO’s 2023 guidance on ethical AI in education and align with SDG 4 (quality education) and SDG 10 (reduced inequalities), emphasizing equitable lifelong learning across generations.

6.2. Digital Symbiosis: A New Paradigm for AI in Education

This study introduces Digital Symbiosis not merely as a descriptive metaphor but as an emerging theoretical state of intergenerational relations in AI-mediated contexts.

In this state, the youth’s digital fluency and the elders’ life wisdom evolve as mutually reinforcing assets through sustained collaboration.

While socio-emotional scaffolding explains the process of overcoming barriers, Digital Symbiosis captures the outcome—a relational equilibrium of reciprocity, empathy, and collective growth.

This construct extends Bengtson and Roberts’ intergenerational solidarity theory by embedding technology as a mediator of solidarity, and complements Ragnedda and Ruiu’s [11] digital capital by reframing resources as co-produced rather than individually possessed.

It also aligns with Feenberg’s ritical theory of technology and Sen’s capability approach [3,29], situating AI as a socio-technical catalyst that can expand or constrain freedoms.

Unlike prior intergenerational learning research that largely remained task-oriented, Digital Symbiosis theorizes a co-evolutionary paradigm: a sustainable state of mutual adaptation where both younger and older cohorts continuously reshape their roles in the digital age.

While further empirical validation is needed, this contribution provides a sociological vocabulary that advances current debates beyond metaphor toward a theoretical lens for enduring relational transformation.

6.3. Concluding Remarks

The empirical findings of this study suggest a possible fourth pathway for AI in higher education, one that moves beyond fleeting Fashion, technocentric Fetish, and utopian Fantasy.

Grounded in local needs and co-constructed with the community, the AI-IDI framework reaffirms that AI’s potential lies in its capacity to connect people, foster solidarity, and support authentic human needs.

Although rooted in Taiwan, the framework demonstrates cross-cultural transferability, offering adaptable insights for aging societies in Europe and for addressing digital inequities in the Global South.

Future research should explore how Digital Symbiosis may translate across cultural systems—e.g., collectivist East Asian societies versus individualistic Western contexts—to refine its theoretical universality.

In doing so, this study offers not only a localized model but also a globally resonant framework, bridging sociological theory, educational practice, and policy debate.

This study thus serves as an agenda-setting framework for future research and policy on AI-mediated intergenerational learning. By articulating AI-IDI as a socio-technical and civic model, it establishes a roadmap for building ethically grounded, culturally responsive, and socially inclusive AI practices in higher education and beyond.

Ultimately, it affirms that AI’s promise is most fully realized when enacted as a humanistic medium for social cohesion and justice.

This study positions itself as a work of conceptual development and exploratory empirical research. Rather than claiming to establish a fully matured theory, it advances Digital Symbiosis as an exploratory conceptual framework that provides a sociological vocabulary for theorizing intergenerational co-evolution in AI-mediated contexts. While the empirical scope is limited to a single cultural setting and a short intervention, the findings offer valuable insights that can inspire further theoretical refinement and cross-cultural validation. In this sense, the contribution of the study lies not only in its local application but also in its capacity to open new avenues for comparative research and policy discussions on digital equity, aging societies, and human-centered AI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.-C.C.; methodology, F.-C.C.; data curation, F.-C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-H.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.-H.C.; supervision, C.-I.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the SOP 1.8 of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan (Section 1.8.4, Item 4), research conducted in general teaching environments for educational assessment, testing, teaching strategies, or effectiveness evaluation is exempted from Institutional Review Board (IRB) review. Our study falls into this category, as it was conducted in a regular university course setting to evaluate teaching effectiveness and student learning outcomes.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary, with the option to withdraw at any time without consequences. All data were collected and analyzed in de-identified form.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4.0, 2025) for the purposes of drafting selected sections of the text, suggesting methodological alternatives, and supporting the interpretation of findings. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Michel-Villarreal, R.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.; Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Thierry-Aguilera, R.; Gerardou, F.S. Challenges and opportunities of generative AI for higher education as explained by ChatGPT. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.A.; Green, B.J. Wisdom in the Age of AI Education. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2024, 6, 1173–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenberg, A. Critical Theory of Technology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn, N. Should Robots Replace Teachers?: AI and the Future of Education; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, M.; Rauschenberger, M.; Schön, E.-M. “We Need to Talk About ChatGPT”: The future of AI and Higher Education. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 5th International Workshop on Software Engineering Education for the Next Generation (SEENG), Melbourne, Australia, 16 May 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NT, USA, 2023; pp. 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, S.U. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. In Algorithms of Oppression; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Compagnucci, L.; Spigarelli, F. The Third Mission of the university: A systematic literature review on potentials and constraints. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 161, 120284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spânu, P.; Ulmeanu, M.-E.; Doicin, C.-V. Academic third mission through community engagement: An empirical study in European universities. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Social Report 2023: Leaving No One Behind in an Ageing World; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ragnedda, M.; Ruiu, M.L. Digital Capital: A Bourdieusian Perspective on the Digital Divide; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2020; pp. 8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson, V.L.; Roberts, R.E. Intergenerational solidarity in aging families: An example of formal theory construction. J. Marriage Fam. 1991, 53, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, F.; Breton, N.; Moreno-Tabarez, U.; Delgado, J.; Rua, M.; de-Graft Aikins, A.; Hodgetts, D. Participatory Action Research. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2023, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurick, R.; Apgar, M. Participatory Action Research: Guide for Facilitators; WorldFish: Penang, Malaysia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, A. Towards a Pedagogy of Intergenerational Learning. In Intergenerational Learning in Practice; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 40–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrott, S.E.; Turner, S.G.; Juris, J.; Scrivano, R.M.; Weaver, R.H. Program Practices Predict Intergenerational Interaction Among Children and Adults. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurani, G.A.; Lee, Y.-H. Intergenerational learning for older and younger employees: What should be done and should not? J. Syst. Cybern. Inform. 2025, 23, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Warschauer, M. Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Van Deursen, A.J.; Van Dijk, J.A. The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. N. Media Soc. 2014, 16, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, C.K.; Scanlon, E. The Digital Divide Is a Human Rights Issue: Advancing Social Inclusion Through Social Work Advocacy. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work 2021, 6, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, L.; Mascia, M.L.; Gierszewski, D.; Walker, C. Barriers to digital inclusion among older people: A intergenerational reflection on the need to develop digital competences for the group with the highest level of digital exclusion. Innoeduca. Int. J. Technol. Educ. Innov. 2023, 9, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]