1. Introduction

1.1. An Overview

The life cycle of women encompasses several pivotal stages, such as education, marriage, family nucleation, motherhood, and work responsibilities [

1,

2]. Each of these critical stages involves various physiological, social, and personal attributes. Considering the contradictions and priorities of these significant stages, women need wise decision-making to achieve a balance. Throughout their lives, women often face a complex and ever-changing relationship between work and family, which is particularly true for women, especially married women [

3,

4,

5]. It is a universal phenomenon and a chronic headache for societies regardless of nation, culture, and discipline [

6,

7]. The strength of this relationship varies depending on cultural, religious, and living standard factors. For women, juggling multiple roles as a wife, mother, and employee can result in inconsistency and imbalance between these responsibilities. Therefore, establishing a balance between work and family obligations is crucial for policymakers and legislators to prioritize. This balance is essential for the stability and productivity of both family and workplace [

8]. Additionally, the transition from college to work often presents a challenge for fresh female engineering graduates [

9].

In conservative societies, there is an ongoing debate regarding the appropriateness of women’s work. This discussion involves economists, sociologists, and religious scholars [

10,

11,

12]. Economists argue that countries experience a loss when well-educated women, who have completed tertiary education, choose to leave their promising careers to focus on family responsibilities. On the other hand, sociologists believe that women’s unpaid work within the family, such as caring for spouses and children, plays a crucial role in national development. Striking a balance and integrating work–family responsibilities is essential for family, nation, and organizational advancements. In contrast, religious scholars advocate for women to stay at home, considering their work as a violation of their modesty [

12]. Furthermore, Yemeni society tends to look down upon dual-earning couples. These conflicting beliefs have a significant impact on women’s opportunities for sustainable careers in conservative societies and create challenges in maintaining a healthy work–family relationship [

12,

13,

14,

15].

To shed light on the social pressures faced by women in the workforce, it is worth noting that both the engineering and medical professions share certain similarities in terms of work conditions. These careers often involve night shifts, irregular and long working hours, and high work pressures [

16,

17,

18]. However, the engineering field is predominantly male-dominated, which exposes women female engineers to additional stress and unhealthy work environments [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Moreover, sociocultural norms tend to be more accepting of women working in medical professions compared to engineering jobs [

16,

18]. In many cases, engineering jobs require women to travel outside the residential areas to industrial complexes, which can cause anxiety for their families. Consequently, the engineering profession becomes an additional source of WFC for female engineers. As a result, organizations and companies may exhibit a preference for hiring male engineers over female engineers due to the nature of the engineering profession, and societal beliefs [

23,

24,

25,

26]. In the conservative Yemeni society, this article holds a particular significance. It aims to explore women’s experiences in the male-dominated engineering field, which is characterized by physically demanding tasks and high work pressures.

1.2. Women’s Education and Work in Yemen

For many years, the underrepresentation of women in employment and education has been a topic of interest for researchers worldwide. However, there is limited knowledge about this in conservative Yemeni society [

12]. To begin, Yemeni legislation ensures the right to education for individuals of all ages, genders, and ethnicities. According to official reports from 2022, the proportion of female students in primary, secondary, public, and private schools in Taiz city (the most populous city in the country) over the past seven years is 50.3% despite the challenges posed by the political crisis. Similarly, female students make up approximately 51.0% of public and private universities in the city. Although the education level in Taiz city is relatively high compared to other cities, the Yemeni education system supports female education. Both male and female students participate in a co-education system implemented in schools and universities, both public and private, regardless of any gender discrimination or societal contempt [

27].

Unemployment rates for Yemeni women are significantly high, potentially reaching 90 percent [

28]. Reports from the United Nations indicated that the ratio of female to male employees in urban areas is below 15%, and this proportion decreases threefold in rural areas [

29,

30,

31]. The education and health sectors are the main government sectors that employ women in Yemen. In Taiz city, the percentage of female teachers in schools is 31%, while at Taiz University it is 36%. This is compared to the global average of 33% of researchers, as reported by UNESCO [

31]. However, there is an unfair distribution of female education, with only 26.8% of rural girls completing lower secondary education compared to 51% of rural males. Poverty plays a significant role in the underrepresentation of girls in education, particularly in rural areas [

28,

32].

The engineering sector deviates from these statistics due to its male-dominated nature, resulting in the lower representation of women [

33,

34]. The enrollment of female students in engineering education is lower compared to other disciplines, possibly due to societal beliefs that reinforce the dominance of men in engineering careers. On average, the percentage of female students in engineering education at Taiz University ranges from 14 to 22% based on official statistics from Taiz University for the period 2005–2022 [

12]. Similarly, statistics indicate that the average female representation in the engineering college at Sana’a University is 22%. The underrepresentation of females in engineering education is not solely attributed to the engineering profession itself but also to societal roles that do not promote females in this field. A survey report revealed that approximately 39% of Yemeni people believe that university education is not necessary for females [

31]. Women face additional social problems in Yemen regarding their education; a recent study indicated that 89% of families do not allow their females to engage online education platforms that allow the sharing of their mobile numbers and other personal characteristics [

34]. However, engineering education equips female engineers with skills and capabilities that enable them to pursue non-traditional job opportunities such as online, office, and computer-related jobs. Females actively participate in online part-time jobs and intermittent work to improve their income [

34].

The Yemeni legislature has established and enacted laws to protect women in the workplace and uphold their rights. Specifically, the Yemeni labor law includes various provisions that address gender discrimination and promote women’s rights in the family, society, and workplace. One notable provision is the recognition of certain benefits for employed lactating women such as the option to have shortened working hours without facing penalties. Furthermore, women are given a sufficient period of paid leave before and after maternity [

32]. The standard maternity paid leave in Yemen is 70 days, with the possibility of an extension. It is important to note that, under Yemeni law, female employees have the right to resign without notice if they experience sexual harassment in the workplace. Women in Yemen have more than legal support—Yemeni society tends to support women in personal and workplace conflicts, including instances of sexual harassment. Women’s claims are generally trusted, and people often rush to their aid in such situations [

12].

Discrimination based on skin color and physical attributes is not widespread in Yemen [

28]. However, there is a notable prevalence of gender-based discrimination in certain career fields, particularly in engineering-related professions. The sustainability of jobs for married females is a factor that can vary due to marriage responsibilities and sociocultural norms. It is important to recognize that the consequences of marriage, such as pregnancy, childbirth, and childcare, often result in frequent absences from work, lower performance, and potentially even opting out of careers.

The understanding of family–work dynamics in Yemen is complex and requires in-depth and systematic studies. In contrast to other societies, Yemeni women face significant societal pressures that often outweigh the pressures related to work and family [

28]. This research investigation aims to measure the intensity of these societal pressures. In Yemeni society, husbands hold the authority to decide whether their wives should pursue employment or not, and this decision is often influenced by religious practices and family expectations. In some cases, husbands may even prevent their wives from pursuing education [

35]. Consequently, women are faced with the difficult choice between a career and marriage, with limited opportunities to strike a balance between the two options.

One major obstacle to female employment in Yemen is the restrictions imposed by families on women’s travel and movement of women. Yemeni women’s job opportunities are typically confined to their immediate geographical area [

12]. Social norms discourage women from seeking employment far from their homes, and those women who defy this norm risk losing social respect and rights. Furthermore, societal practices, often supported by religious scholars, tend to devalue women’s work and encourage them to stay at home. These factors have significantly impacted the representation of women in the workforce.

However, this traditional social role has been partially disrupted within the community, potentially due to the devastating effects of the ongoing war on family finances. Consequently, many families have embraced the concept of dual-earning couples and independent families, where both husbands and wives work outside the home, without a partner solely responsible for household chores [

28,

32]. Currently, numerous families permit their daughters to pursue employment opportunities, both conventional and unconventional, whether in close proximity to their family home or at a distance [

31]. According to the current survey, it is revealed that 51% of employed female engineers held positions that were located far from their hometown.

1.3. Conservative Society Definition

A conservative society is a social system that emphasizes maintaining traditional values, cultural practices, and established institutions, particularly those rooted in religion, family, and community [

36,

37]. In such societies, there is a strong preference for preserving social, political, and moral norms inherited through generations. Change is viewed with resistance and caution, especially when it threatens core values or disrupts social stability [

38].

In many cases, religions shape a conservative society’s moral framework and guiding principles, while religious institutions provide a fertile foundation for laws, social roles, and customs [

39]. Such environments influence political ideologies and direct the behavior of individuals within the community. In a conservative society, the state and religion are often intertwined, with both working together to uphold established norms and preserve societal order.

Conservative societies value traditions and prioritize social hierarchy, authority respect, and community cohesion; roles and responsibilities are clearly defined, and societal values are transmitted through generations. It was identified that Islamic work ethics significantly enhance the connection between job satisfaction and job performance [

40].

Conservative societies tend to be more insular and less receptive to outside influences, with rural areas often being more so compared to urban ones [

8]. Yemeni society, characterized by high poverty rates, a patriarchal culture, husbands’ full authority, a toxic workplace environment, and a closed society, exemplifies this trend of the conservative society [

27,

41]. The ongoing civil war has further isolated Yemen, making it even more challenging for Yemenis to travel abroad and engage with diverse cultures and experiences that permit them to oppose the conservative views they were raised with. As a result, from this point of view, the Yemeni society is described in this study as being thoroughly conservative.

This study aims to examine the balance between the work–family and engineering career for female engineers in Yemeni conservative society, both single and married. It seeks to understand how a country’s economic and political situation impacts women’s work–family relationships and performance. This research primarily focuses on identifying social barriers that hinder women’s employment. To gain insights into the WFC within an engineering environment and a conservative and unstable society, the study will involve employed female engineers, a sample of their husbands, as well as numerous senior and experienced engineers. The research problem will be explored by considering various social, educational, and economic variables that women in Yemen face, while also respecting their privacy and rights.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of the Work–Family Conflict

Work–family conflict is a well-documented global social issue that contiguously impacts the performance of employees, employers, and families [

6,

7]. It possesses warning tension that arises from imbalanced roles between work and family, causing stress, role overload, and a reduced sense of well-being [

42,

43]. Additionally, it has a bidirectional effect, in which work interferes with family roles, and vice versa. The severity and complexity of this interference varies with societal expectations, gender roles, work culture, and family maturity.

The engineering profession is historically considered male-dominated, with minor roles for women [

42,

44]. The problem is more pronounced for female engineer employees engaged in physically demanding, field-based tasks, night shifts, and frequent traveling. Integrating work and family responsibilities can be particularly challenging for women in engineering, as they often encounter obstacles related to career progression, heightened stress levels, and difficulties in balancing professional and domestic duties [

43]. This three-dimensional conflict increases psychological stresses and may, in some cases, lead to suicide among employed women [

45]. Additionally, multiple studies have proved the detrimental effects of WFC on employees’ physical and mental health [

6,

46,

47].

The work of female engineers in traditionally male-dominated fields aligns well with the concept of “solo status” in social psychology. This term describes the behavior of individuals living in a group while belonging to segregated categories based on sex, language, or religion [

8]. Individuals in such groups are susceptible to social identity threats when they are treated as low-status members. Female engineers in the engineering profession exhibit similar behavior patterns.

2.2. Influences of Work–Family Conflicts

Work–family conflict has many internal and external influences; recent studies have shown that internal personal factors of female engineers play a major role in obtaining jobs and balancing work–family relations, compared to external influences [

12,

48]. However, various external factors related to family and societal roles can greatly amplify WFC. These factors include the patriarchal nature of society, responsibilities related to spouses and childcare, as well as household chores [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53].

Marriage, in particular, is seen as a significant milestone in a woman’s life and has far-reaching effects on various aspects such as personal life, future prospects, family dynamics, career progression, and living standards [

54]. Studies have shown that marriage tends to have a greater impact on career disruptions in urban areas compared to rural areas [

3,

54]. Moreover, married women often experience higher rates of absenteeism due to family responsibilities and challenging work environments. The high fertility rate and the demands of childbearing also contribute negatively to job continuity [

12]. It has been also observed that when husbands or family headmen have lower levels of education compared to their female counterparts, it can lead to misunderstandings and mental stress for women, significantly affecting their roles both at work and within the household [

55]. Social traditions play a major role in shaping work–family dynamics for women engineers in conservative societies [

25], making them faced with a double burden: the demanding nature of their profession and the societal expectations of their role within the family.

Needless to mention, the patriarchal culture prevalent in conservative society extends into the workplace, influencing the professional and leadership roles that women can effectively pursue within organizations [

28]. This cultural backdrop often limits the opportunities available to female engineers. Experts note that women in engineering typically face limited career choices, being pressured to either conform to the male-dominated norms of the field or accept less challenging and lower-status tasks [

23]. As a result, many women in engineering careers find themselves concentrated in lower-level positions, face barriers to promotion, and experience higher rates of attrition from the workplace.

WFC has become increasingly prominent, driven, in part, by the growing reliance on modern technologies, such as contemporary workplace structures, social media platforms, and generative AI tools. The use of public social media for work purposes during after-hours work positively affects work engagement but amplifies WFC, ultimately leading to decreased work engagement [

56,

57]. Recent research articles have been directed toward the impact of generative AI tools on work-life balance. The results indicated that AI managerial capabilities and AI infrastructure agility impact work-life balance, thereby empowering employees’ performance in the workplace [

58,

59].

Taken as a whole, social support and good financial conditions are key factors to support work–family relationships and make them peaceful [

60]. These variables can have a positive impact on female engineers, motivating them to pursue leadership roles, achieve a better work–family balance, and ultimately enhance their job satisfaction [

61,

62,

63]. On the other hand, social and family pressures can act as demotivating factors for female engineers, leading them to consider leaving the field of engineering both in terms of education and career [

64].

To effectively address work–family balance, several common policies are crucial for employers. These policies include flexible work schedules, job-sharing arrangements, work-from-home options, on-site childcare facilities, parental leave policies, strong support from managers and supervisors, and family or spousal support [

4,

65]. Without workplace support, women are forced to make difficult decisions in physically demanding careers, often sacrificing their careers for family obligations or opting for less demanding roles, which can hinder career progression and job satisfaction.

2.3. Theoretical Frameworks on Work–Family Conflict

Various theoretical frameworks have investigated the complex phenomenon of WFC for different societies of different features to highlight the collaboration between family and work [

61,

62,

66]. It is well to mention that the engineering field, traditionally dominated by men, often places women in a position where they look isolated from the work environment, their contributions are treated with less promotion, and they may face additional pressure to prove their competence, further exacerbating the effects of the so-called “solo status” in physiology [

6]. These studies have primarily focused on measuring and achieving a balance in WFC. All work–family theories propose different outcomes for the well-being of individuals, families, and organizations (stockholders). These models have contributed to a comprehensive understanding of the nature of WFC and strategies for its management [

61,

67]. However, their applicability and relevance in the context of conservative societies require a critical review, particularly when considering the influence of cultural and structural factors.

The spillover theory suggests a bidirectional relationship between the work and family domains, where influences from one domain can impact the other in terms of happiness or tension [

67]. It posits that the emotions experienced at home can spill over into the workplace, and vice versa. Additionally, the theory proposes that behaviors exhibited at work can directly affect one’s personal life. It assumes that individuals constantly navigate between their family and work roles, and the balance between the two depends on the permeability and exchange of information between the domains [

8]. Case studies conducted in various societies and disciplines have led to refinements and exceptions to the spillover theory, considering community attributes and peculiarities [

48,

49]. The theory aligns well with professions that have demanding, high-stress, and predominantly masculine characteristics such as engineering [

8,

68]. In the same context, the border theory suggests that increasing similarities between the work and family domains can facilitate achieving a better balance between them [

8].

Spillover Theory provides a better approach to describing and resolving WFC, especially for women in conservative societies and the man-dominated engineering profession. In such an environment, the intensity of peaks related to WFC is extremely high for both parties. On one side, the patriarchal culture in the family and social traditions maximize its intensity, and on the other side the extensive pressures on female engineers in the workplace. Therefore, spillover theory is so suitable, since it recommends enhancing permeability and volumetric information exchange between the domains.

Unlike the spillover model, the compensation theory primarily focuses on individuals and their experiences in balancing responsibilities between the family and work domains. According to this theory, deficiencies in the work environment can be compensated for in the family domain, where activities such as rest and weekend enjoyment help alleviate work-related stress experienced during working days. The theory suggests that non-work activities serve as buffers for work dissatisfaction, and vice versa. It assumes that effective communication between the work and family environments is necessary to facilitate successful compensation [

69].

While compensation theory offers an optimistic view of the potential for balance between work and family, it assumes that individuals can actively control how they balance the two domains. this theory may not be fully valid due to the structural limitations women constantly face in balancing work and family. Women, especially in rural or conservative areas, often lack the resources or societal support to compensate for the stressors in either domain. Particularly, female engineers face heavy work duties, promotion ignorance, and limited family time making them unable to balance WFC in either direction due to cultural backgrounds, patriarchal culture, and limited employer support.

In contrast, the segmentation theory posits a complete separation and irreversible relationship between the work and family domains. According to this theory, individuals can effectively perform in the work environment without any influence on the family environment, and vice versa [

67]. The segmentation model assumes no communication between work and non-work roles. This model is particularly applicable to low-level jobs that do not require high skills or experience, where organizational stakeholders have numerous employee alternatives.

This theory is no way working for women in conservative societies and engineering profession, where it is difficult for women to segment these domains. For instance, in engineering careers, women often cannot fully separate the two spheres, as family and work responsibilities overlap. Furthermore, the lack of policies such as flexible work hours and parental leave further complicates the possibility of segmentation.

In conclusion, while the theories provide valuable insights into the dynamics of WFC, each framework has its limitations, particularly when applied to conservative societies and male-dominated professions such as engineering. Given the unique challenges posed by these contexts, including the high levels of stress and societal pressures faced by women in engineering, the Spillover theory appears to be the most suitable for understanding the relationship between work and family. This theory emphasizes the exchange of information between work and family domains, helping to explain how experiences in one area influence the other and how balance can be achieved amidst the challenges presented by these environments.

In-depth studies exploring the relationship between family and work dynamics in male-dominated employment and societies with prevalent misconceptions about women’s employment and leaving their homes are limited. This study aims to in-depth investigate the WFC experienced by female engineers in a Yemeni conservative society through statistical analysis.

The research design involved multiple surveys targeting employed and unemployed female engineer graduates, senior engineers and managers (both male and female), and husbands of female engineers in Yemen. Implementing multiple surveys provides powerful insights for better understanding the dynamics of WFC from different views of family, spouse, society, and employer. This study is unique as it targeted the conservative society of Yemen where a dearth of social studies, especially studies concerning female engineers, who often face multiple forms of discrimination in the workplace and family.

3. Research Hypotheses and Design

Based on the previous discussion, explicit variables have been designed and elucidated. Marital status, spouse support, family financial conditions, marriage responsibilities, social and religious beliefs, job geographical location, working hours, and job nature are investigated as variables affecting female engineer’s job opportunities, continuity in a job, and WFC. Quantitative cross-sectional surveys are designed to validate the goal and questions of this work and interpret the relationship between variables. To validate the hypotheses of this research, the design suggests communicating female engineer graduates, senior engineers and managers, and female engineers’ husbands. The research hypotheses of this study are organized as follows:

H1. The marital status of women in conservative societies is a critical factor influencing their job opportunities and job continuity.

H2. Marriage acts as a job constraint for women in conservative societies, negatively impacting their work performance and job continuity.

H3. The behavior of spouses in conservative societies exacerbates WFC, particularly for women in engineering professions.

H4. Women’s job opportunities in Yemen are limited by geographical location, social norms, and religious beliefs.

H5. The pressures from family to work are greater than the pressures from work to family in conservative societies.

H6. Employed women in conservative societies are less likely to get married compared to unemployed women.

H7. Conservative societies do not accept women working in tough engineering jobs that require fieldwork, frequent travel, and night shifts.

H8. Hard financial conditions of families in conservative societies positively impact work–family balance.

H9. Online and flexible-schedule jobs positively impact work–family balancing for married women in conservative societies.

4. Research Methodology

A quantitative approach was employed to address the research questions. Due to the multiple domains that affect the dynamics of WFC for women in engineering professions in the Yemeni conservative society, three different questionnaires targeted employed and unemployed female engineering graduates (130 respondents), female engineering graduates’ husbands (20 respondents), and senior engineers and managers from various organizations (60 respondents).

Questionnaires were designed and distributed to the respondents from May to July 2023, and the research team applied strict procedures to ensure the correct respondents for each questionnaire. Questionnaires were focused on variables related to conservative societies and their impact on the WFC for women in engineering profession. Furthermore, focused questions were asked to investigate the performance of married female employees in the workplace and the impact of marriage on job opportunities and job continuity. The responses were analyzed to explore the interrelation between different variables, and coherent results were obtained.

Senior engineers and managers were selected as respondents, representing organizations and employers in Yemen. The sample was selected based on the following criteria: (1) they can be of any gender, (2) they have a minimum of 5 years of experience, and (3) they have emerged in managerial positions. These specific characteristics were chosen to ensure consistent and meaningful findings regarding the dynamics of work–family–engineering conflict. The respondents stem from a wide range of sectors such as governmental (23.2%), commercial (19.6%), industrial (39.3%), education (14.3%), and others (3.6%).

This study also communicated with female engineering graduates from Taiz University, Yemen. Specifically, graduates between 2012 and 2023 were considered in the sample. The sample of female engineers was diverse, comprising the following categories: (1) single and married females, (2) employed and unemployed females, (3) fresh and old graduates, and (4) graduates from a wide variety of engineering disciplines. This diversity provided valuable insights into the job opportunities, workplace behavior, and their relationship with their families and husbands, particularly during their employment. The focus of this study is particularly relevant as female engineers often face unique challenges stemming from the male-dominated nature of the engineering profession and the societal expectations placed on them in conservative societies, where husbands dominate wives’ decisions and impose more control upon them.

To explore the WFC faced by female engineers in the Yemeni conservative society, especially by their husbands, we developed a structured questionnaire, consisting of approximately 25 questions. This questionnaire was administered to 20 husbands of female engineers. The questions were designed to assess the level of support provided by husbands in various areas, including engineering education, the engineering profession, job opportunities, job continuity, and balancing work–family responsibilities in the male-dominated engineering profession. This questionnaire was distributed to the targeted respondents with the assistance of married female engineers, who handled it to their husbands.

All questionnaires were carefully designed in the Arabic language using a 5-point Likert scale, and the responses were subsequently translated into English for further analysis. The questionnaires were meticulously prepared and constructed using Google forms and distributed to the respondents through email and social media networks by members of the research team. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS software 23, where the mean and standard deviation were calculated and the relationships between variables were interpreted. The outputs then were organized, presented, and interpreted through diagrams, histograms, figures, and tables.

5. Results

The results of the current study are presented, analyzed, and interpreted in this section. Specifically, the research questions were committed to the three groups targeted at the questionnaires. These questions, along with responses, are organized and presented in the following subsections:

5.1. Husbands Perspectives

Husbands’ support is a significant factor in achieving a successful career. The present study involved consulting husbands of female engineers, including those working domestically and internationally. These husbands were surveyed on many aspects such as education, work, and social issues related to females, serving as a family and society sample.

Table 1 summarizes viewpoints of husbands regarding their roles in work–family balances for their wives in engineering profession, and many social issues related to women in employments, engineering profession, and engineering education. Although husbands constantly support their wives in searching for and obtaining jobs in their fields (µ = 4.13), they show extremist opinions regarding their wives’ jobs that require night shifts, frequent travel, and fieldwork, with almost complete rejection (µ = 1.30). Also, it is evident that most husbands support their wives in pursuing careers within their specific fields of expertise, but more than 50% of them discourage their wives from permanent full-time jobs.

The survey results from the husbands revealed that their views on women’s rights in education and employment were not like their general statements. Despite being part of an educated and sophisticated class in society, their opinions did not align with the broader view of the Yemeni community. Specifically, their responses to the statements “Women should stay at home and should not go for jobs” (µ = 3.11) and “Women should not pursue university education; basic school education is sufficient for them” (µ = 3.15) were inconvenient and not in line with societal norms.

Two more critical social issues were answered from husbands as a society sample. these social issues related to marriage opportunities for employed women in the engineering profession. They almost reject an annoying statement related to marriage opportunities of employed women in Yemeni conservative society (µ = 1.94), which states that “Employed women are not suitable for marriage”. However, their opinion was negative (µ = 2.64) regarding the statement “The engineering profession reduces marriage opportunities for women”.

5.2. Senior Engineers and Managers Prospectives

Senior engineers and managers who had experiences dealing with engineering profession and related employers are crucial to understand the dynamics of WFC in the conservative society of Yemen.

Table 2 represents the results of about 60 senior engineers and managers from different industrial, commercial, and education sectors related to female engineers at job. The analysis focuses on many variables arises in Yemeni conservative society related to female engineers at workplace.

Women face multiple barriers during job hiring. Particularly, women in Yemen face problems in getting a job related to the engineering profession, marital status, and even their dress and appearance. Regarding the discrimination of women in the engineering profession, respondents indicated that employers in Yemen are a part of this discrimination (µ = 3.6). Also, there is apparent discrimination against married women than single ones; respondents agree that they prefer to hire single women than married women (µ = 3.37). In conservative societies, women may lose job opportunities because of their wear and appearance. Women who wear Neqab (a dress covers the whole face of woman) have less chance of obtaining a job (µ = 2.57) and the job chances for beautiful women are higher than others (µ = 2.11). Although managers and senior engineers have downplayed the impact of a woman’s appearance and dress on her chances of getting a job, it is still a significant problem in Yemeni conservative societies.

The responses from senior engineers and managers are compelling, providing insights into the performance of female engineers in the workplace, including their strengths, weaknesses, and the impact on their daily lives. Respondents from different industrial, construction, commercial, and educational sectors expressed negative responses regarding the women’s eligibility of promotion (µ = 2.9) and senior positions (µ = 2.46) in the workplace, despite their high evaluation. Additionally, respondents indicated their opinions regarding several issues related to female engineers in the workplace, reflecting perspectives commonly practiced in Yemeni conservative society. The responses include: (1) women engineers are wrong candidates for additional work (µ = 2.56), (2) they have high absenteeism rates at work (µ = 3.11), (3) they cannot deal with work pressures (µ = 3.47), (4) they fit well for office work than fieldwork (µ = 3.47), and (5) sexual harassment in the workplace poisons work–family relationships (µ = 3.61).

Industrial managers and senior engineers gave a good impression of the performance of female engineers at work. They indicated that the engineering profession is a viable career option for female engineering graduates and their performance at work is better than other disciplines (µ = 3.77). In this regard, respondents agreed that female engineers are professional at computer-related duties at work (µ = 4.72), and their overall evaluation is high (µ = 3.98).

5.3. Female Engineer Graduates’ Perspectives

Work–family–engineering relationships were investigated from the viewpoint of spouses as members of families and from the managers and senior engineers as employers, presenting the viewpoints of female engineers is pivotal in addressing the dynamics of the problem.

Employed female engineers indicated relative support from their husbands regarding searching for a job in their engineering fields (µ = 3.56) as shown in the

Table 3. Their viewpoints regarding difficulties faced by women engineers in work are extremist; they see that husbands completely disagreed with jobs with night shifts and travel requirements (µ = 1.5), and did not support wives’ permanent full-time jobs (µ = 2.23).

Female engineers delivered clear statements regarding many discriminating issues against women in Yemeni conservative society, such as: (1) Employed women are not suitable for marriage (µ = 1.5), (2) Women should stay at home and should not have a job (µ = 2.04), (3) The engineering profession reduces marriage opportunities for women (µ = 1.61), and (4) Women should not pursue university education; basic school education is sufficient for them (µ = 1.07). Also, Female engineers expressed that Yemeni society supports women’s basic, university, and higher education.

The results from these three categories of participants indicated that female engineers possess proficiency in computer skills, information technology, and computer-related administrative programs, and their work performance is rated as good. However, their performance tends to decrease under work pressures or when working overtime. Also, respondents from the three categories unanimously agree that women are unsuitable for jobs that involve long hours, night shifts, or travel outside their geographical areas. The results from these three categories of participants indicate that married female engineers exhibit relatively lower efficiency than their unmarried counterparts. All male respondents, including husbands and senior engineers, agree that women should not be assigned to jobs of night shifts and frequent traveling. Additionally, it is worth noting that some female engineers acknowledged that their engineering specialization has impacted their marriage prospects. Specifically, 35.3% of female engineer participants expressed that, if given the chance, they would choose a different specialization instead of engineering.

All participants responded positively, stating that the engineering profession is well-suited for women. Furthermore, their responses uniformly rejected the offensive notion that “employed female engineers are not suitable for marriage” and expressed disagreement with the discouraging statement that “engineering as a profession reduces marriage prospects for girls”. They also encouraged female engineers, demonstrating that they can successfully navigate engineering education in colleges and thrive in the engineering profession in the workplace.

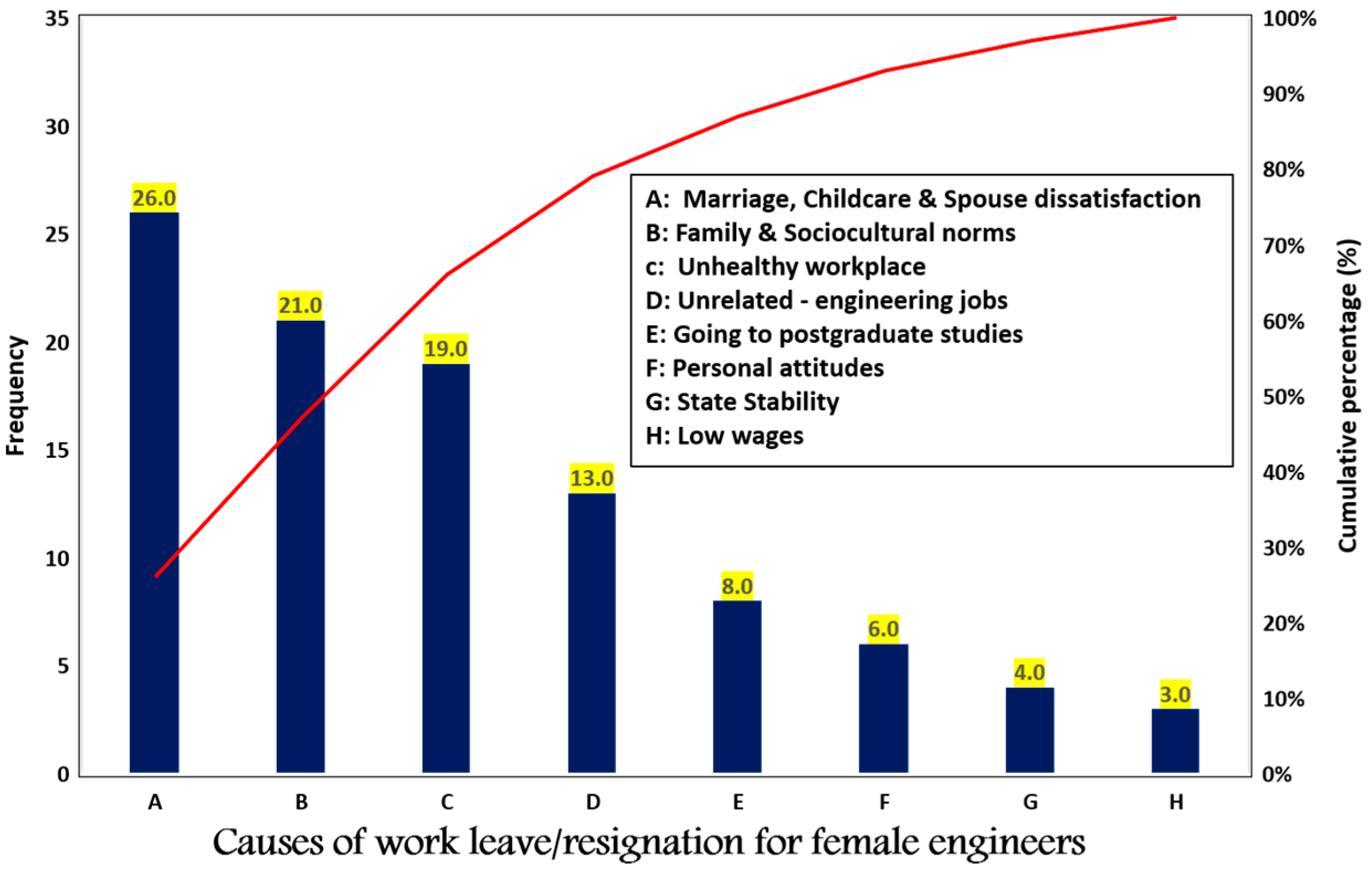

Female engineering respondents (130 responses), both employed and unemployed, married and unmarried, were asked to order the main causes affecting work–family–engineering relationships in the Yemeni conservative society. The answers were then organized and presented in the Pareto chart shown in

Figure 1. The graph provides insights into the primary reasons for work resignation among female engineers in Yemeni society. The graph also deeply expresses marriage as a main variable and its consequences as the leading cause for employed female engineers leaving their jobs.

The analysis of the Pareto Chart (

Figure 1) showed that pressures from family to work are higher than in the other direction in the conservative society of Yemen; marriage and its consequences represent 26%, followed by family responsibilities at 21%. These findings indicate that family and societal pressures on the work domain represent a cumulative score of 50% of the total causes of family–work–engineering conflict in the Yemeni conservative society, which supports the fifth Hypotheses of this research.

The negative effect of marriage on women’s performance in the workplace is extended to their education in college in conservative societies The survey results revealed that married female engineers, both those who married before and during college, had an average overall grade of approximately 4.93% lower than unmarried females. Moreover, unmarried females tended to complete their college studies at a relatively faster pace than their married counterparts. Married women also showed limited response to the development of employability skills and self-efficacy traits, aligning with previous studies in the literature [

12]. These findings undoubtedly confirm that marriage hurts a woman’s job prospects, workplace behavior, and educational performance, supporting the first and second hypotheses of this research.

Additional supportive findings of this survey studies yielded the following insights regarding marriage, work, and female engineer statistics: (1) 68% of female engineer graduates in the last decade in Taiz state are employed in temporary or permanent positions; (2) 52% of employed female engineers are single, while 48% are married; (3) a surprising finding indicates that all employed female engineers in the industrial and construction sectors are unmarried, while married female engineers have left their jobs; and (4) 54% of employed female engineer graduates work in the education and academic sector, with a majority holding temporary positions.

Financial conditions and wage rates of female engineers and their families are important parameters affecting the work–family–engineering relationship.

Figure 2 shows statistics related to the average monthly wages of male and female engineering graduates in Yemen currently. The data presented in

Figure 2 reveal that approximately 21% of male engineers earn more than USD 1000 per month, while no female engineers fall into this category. Similarly, 31.6% of male engineers earn more than USD 500 per month, compared to only 3.5% of female engineers. Consequently, the average monthly wage for female engineers is USD 145.73, whereas male engineers earn an average of USD 557. This indicates that male engineers earn approximately 3.822 times more than their female counterparts.

In addition to the limited promotion of women to senior positions in Yemeni conservative society, the low average wages for women in the workplace further highlight gender discrimination in terms of incentives, wages, and career development for female engineers. Furthermore, the significant income disparity between males and females in Yemen negatively impacts work–family relations. It supports pressures imposed by husbands and families on females to leave their jobs.

Various factors explaining the reasons behind this large disparity of average wages among males and females, which are related to the conservative features of Yemeni society, are described here. One plausible explanation is the greater freedom of movement afforded to males, enabling them to explore better opportunities both within and outside the country. In other words, male engineers are often free from family pressures, sociocultural norms, and geographical limitations imposed on female engineers in conservative societies. In addition, the prevailing belief in male dominance of the engineering profession contributes to increased job opportunities for male engineers. Lastly, the findings of the female engineer questionnaire indicate that marital status does not impact wages. Both married and unmarried employed females receive the same wage rate.

6. Discussion

The relationship between work and family is complex and influenced by differing factors such as societal norms, religious beliefs, economic conditions, familial dynamics, and the nature of work itself. In the conservative Yemeni society, historical and social legacies, religious beliefs, and challenging economic conditions contribute to a unique and intricate discussion of this issue. It is essential to recognize that managing the work–family interface responsibility lies not solely with the employees but is a shared collective responsibility involving the individual employee, their family, society, and the work organization. This discussion explores the relationships between work, family, and engineering in both directions.

6.1. Work-to-Family Disruptions/Enrichments

In most case studies conducted worldwide, it has been observed that the pressures originating from the workplace towards the family tend to be more intense compared to the other direction [

70,

71,

72]. These pressures are prevalent across different locations and can manifest in various forms, such as rigid work schedules, negative control from supervisors, toxic work environments, instances of sexual harassment, night and irregular shifts, sudden changes in attendance, lack of training and promotion opportunities, and field visits, among others. The presence of one or more of these influences can have a detrimental impact on the well-being of employees and their ability to fulfill their family roles effectively. Therefore, it is crucial for organizational decision-makers, including managers and supervisors, to prioritize the work–family balance. This can be achieved by creating a healthy work environment and implementing flexible work schedules [

7,

73,

74]. Work schedule flexibility and control play a significant role in promoting work–family balance and enhancing employee and organizational outcomes. Supervisors should offer schedule control with flexibility in when, where, and how the work is performed [

73]. This necessitates a high level of responsibility from both the employees, who should be willing to accommodate flexibility in attendance and reduced working hours, and the work organization, which should facilitate these arrangements [

75]. The assignment of illegitimate and overwhelming tasks by supervisors or managers to employees is a key factor that negatively contributes to WFC [

76,

77]. On the contrary, a recent study suggests that the use of information exchange and communication technology can have a positive impact on the work–family relationship [

78]. Moreover, the individual characteristics of both employees and supervisors play a fundamental role in influencing the spillover of WFC [

79].

The current political crisis and economic downturn have resulted in a lack of job opportunities and weak official oversight over organizations [

12]. This has led to female engineer employees enduring workplace stresses and toxic environments, regardless of the negative consequences on their lives [

28]. In other words, women have had to maintain a work–family balance due to low family income by enduring more patience with work pressures from individuals and families. Furthermore, employees lack protection from employers regarding unjustified job dismissals or adherence to labor laws. Consequently, employees lose job security and prestige, as employers can dismiss them for insignificant reasons without considering labor laws. The nature of engineering jobs also plays a significant role in excluding women from obtaining sustainable employment [

80]. Employers often advertise job openings exclusively for male engineers, denying female engineers their right to equal job opportunities. Unfortunately, influential individuals in conservative Yemeni society often show contempt for women’s work, resulting in reduced job opportunities, social respect, and marriage prospects for women. This discourages many women from pursuing employment. As a result of these economic hardships, the currency and wages have collapsed. According to survey results (

Figure 2), the average monthly salaries of female engineers are only USD 145, with more than two-thirds earning less than USD 100 per month.

Governmental policies have been implemented to provide legal protection for employees, including specific provisions for female employees. The Yemeni Labor Law has indicated equal opportunities for both men and women in obtaining employment, while also recognizing and addressing the physiological and social differences of women. These policies helped to provide certain privileges and protections for women during and after obtaining a job.

In addition to the general work pressures, the engineering profession is known to impose a higher probability of work pressure on its employees, particularly female engineers. Engineering is a predominantly male-dominated and demanding career that often involves long work hours, unexpected maintenance tasks, night shifts, challenging assignments, fieldwork, and frequent travel [

64,

81,

82]. Furthermore, many industrial companies are located far from residential areas and city centers, requiring daily commuting for employees. These characteristics of the engineering profession are often not well-received by husbands and other male family members when it comes to their female counterparts. As a result, the engineering profession can contribute negatively to WFC and challenges for female engineers, which is in line with Hypothesis H7.

Industrial jobs often require employees to work close to production lines and dynamic machines, which can involve physically demanding tasks and carry a risk of work-related accidents. It is often perceived that female engineers may not be adequately prepared for such environments. Additionally, certain engineering careers may be adapted to harsh outdoor working conditions, leaving little room for flexibility in terms of work relocation. In the context of engineering jobs, women may feel pressured to either conform to masculine workplace behaviors or accept lower positions with diminished expectations. Unfortunately, this can lead to frustration and, in some cases, result in the decision to resign from their positions [

23,

25].

Workplace sexual harassment, bullying, and incivilities are critical social problems in conservative and religious-based communities [

83,

84]. This sensitive issue was confirmed by managers’ responses in the survey, indicating its serious impact on female employees’ job continuity in Yemen. However, the nature of the religious controls imposed on female employees reduces its intensity. Society obliges women to be modest and not engage in discussions outside the framework of their job duties. Furthermore, wearing the hijab for female employees contributes to reducing the possibility of sexual harassment.

Female employees’ responses indicated a noticeable change in their supervisors’ behavior and the organizational dynamics before and after marriage. Employers often struggle to acknowledge and accommodate the dual role of female employees in balancing their family and work responsibilities. Consequently, female employees may experience a loss of appreciation and incentives that they were accustomed to receiving before marriage. These circumstances can contribute to career burnout among female employees.

Finally, online jobs and remote work options contribute to achieving a better work–family balance. Approximately one-third of female engineering graduates engage in temporary online jobs from their homes to supplement their income, which supports hypothesis H9. Single female engineers tend to have more online work opportunities than married females, potentially due to greater mobility freedom and fewer family responsibilities. It is important to note that online tasks and remote work require flexibility in attendance and depend on the organization’s policies and job requirements [

85]. Given that married females often have more family responsibilities, they are well-suited for online and remote work arrangements. Additionally, families residing far from workplaces and low wages pose significant barriers to the employment of married women.

One prevalent barrier to female engineers’ employment is being placed in unrelated roles. The male-dominated nature of many engineering jobs makes this problem more intense, causing a psychological strain of working in non-engineering positions and then magnifying WFC. Placing women in positions unrelated to their educational path results in job insecurity and instability. Furthermore, the continuous exposure to advertisements on social media and web pages promoting postgraduate opportunities, often abroad, motivates many female engineers to leave their jobs and pursue higher education. In this regard, female engineers’ survey findings indicate that 11% of female engineer graduates have enrolled in postgraduate studies.

Female engineers face the challenge of proving their excellence and high performance in their roles despite the physiological and masculine nature of the workplace. They strive to continue their work without interruption. Interestingly, despite the country’s instability, insecurity, and low wages, these factors, as depicted in

Figure 1, do not appear to be significant reasons for female engineers to leave their jobs. This could be attributed to the lack of alternative job opportunities and unfavorable economic conditions, supporting research hypothesis H8.

6.2. Family-to-Work Disruptions/Enrichments

Disruptions from family and society to the workplace will be discussed given the Yemeni conservative society’s determinants. The patriarchal culture of parents, husbands’ full control over their wives, marriage responsibilities, religious beliefs, social traditions, and family income are critical variables affecting women in the workplace.

The logical perspective suggests that families should provide comprehensive support to female employees to enhance their performance in the workplace and contribute to the overall family income and well-being. In other words, family and spousal support play a significant role in balancing work and family responsibilities. However, this claim may become invalid in conservative societies, especially for married females who are exposed to extreme family pressures. Family roles often take precedence over work roles for female employees after marriage, leading to potential disruptions and conflicts between the two parties. Consequently, married women may face fewer job opportunities compared to their single counterparts due to various sociocultural beliefs that restrict married women from pursuing employment. This claim was confirmed by senior engineers’ and managers’ questionnaire responses, which stated that they prefer hiring single women over married ones and that the performance of females decreases after they get married.

Marriage is often cited as one of the primary constraints in this regard. In conservative societies, husbands may express positive theoretical views about women’s work, but when asked if they would allow their wives to pursue employment, they often respond negatively without hesitation. The results inferred from husband’s questionnaire in the present study confirmed this claim and expressed the negative impact of spouse pressures on the WFC.

This study inferred that socio-cultural norms negatively influence the relationship between marriage and the workplace for females. It revealed that the employment of female engineers can reduce their chances of getting married, supporting the 6th hypothesis of this research design. Additionally, married female engineers may face challenges finding job opportunities and may experience higher work resignation rates than single women. A significant proportion of married women engineers who participated in the questionnaire reported that their husbands prevent them from pursuing full-time or part-time employment. Furthermore, 23% of employed female engineers left their jobs immediately after getting married, and many unemployed married women no longer actively seek employment. Husbands often encourage wives to leave permanent employment, particularly in careers that require long working hours and heavy responsibilities, which was indicated clearly by senior engineers’, managers’, and husbands’ responses in the present study. In some cases, women may face restrictions on their freedom of movement, access to services, and participation in the community [

8,

28], without their husband’s prior permission. Additionally, the husband’s family may disapprove of their daughter-in-law’s job and pressure her to resign and prioritize family responsibilities. Not only that, but a recent study also conducted in Yemen for female engineering students indicated that about 89% of their families prevent them from joining online lecture platforms that require presenting identity and mobile numbers [

34].

The prevalence of dual-earning families in Yemen remains relatively low, and such arrangements are often viewed as shameful and unethical [

32]. The prevailing cultural norms in many Yemeni families dictate that the husband should be the primary breadwinner, while the wife’s role is traditionally seen as being within the household.

In conservative societies, women often face significant and painful consequences [

12]. Parents may financially exploit their employed daughters, viewing their monthly salary as a stable source of family income [

32]. Unmarried employed women typically contribute to their family’s living expenses, which is common in low-income families facing severe economic conditions. Aggressive behavior can arise within families, with parents sometimes delaying or even preventing their daughters’ engagement, citing concerns that the husband will rely on his wife’s salary to support his independent family, resulting in the parent’s loss of a permanent source of income. In some cases, families even impose conditions in the marriage contract requiring their married daughters to contribute part or all their salaries to their parents. While this phenomenon is less prevalent in urban areas, it occurs frequently in rural and impoverished societies. Unfortunately, this undesirable situation contributes to a low percentage of married females seeking employment.

Despite being highly educated in their communities, engineering females face negative consequences. Socio-cultural traditions dictate that men often prefer to marry women with lower education levels than themselves. As female engineers attain higher levels of education, their chances of marriage decline [

12]. This behavior can be attributed to men’s desire for guardianship and control, which perpetuates gender discrimination in Yemeni society. The present study supports this claim since 19 out of 20 husbands consulted had an education level equal to or higher than their wives. In conclusion, the impact of marriage on WFC is significant in Yemeni conservative society and aligns well with research hypothesis H2 and findings from other studies in the literature [

3,

49,

51].

Another disruption from the family domain to the work domain is that families in Yemen do not allow their females to look for jobs far from their permanent residency with family. This social belief influences female engineers’ tendency to search for suitable placements, plausibly due to the family’s frequent relocation, arising from the ongoing war in Yemen. In some cases, leaving a job is unintentional due to the family’s relocation to a distant location, and social customs prohibit girls from living outside the family home without a guardian, even for a single night. The ongoing war in Yemen has further increased the frequency of family relocations due to safety concerns and economic hardships, compelling employed women to leave their jobs and join their families. Over time, married women often have multiple children, given the high fertility rate in Yemen (6.00 children per family) [

28,

31,

32], which ultimately poisons work–family relationships, leading employed women to leave their permanent jobs.

Of note, the ongoing war drastically affected the transportation sector in Yemen [

32,

84], and therefore tricky transportation of employees between rural and urban areas is the prevailing case, which is compatible with research hypothesis H4. Survey findings recorded that ~9% of female engineers live in rural areas with low participation in the paid workforce. This percentage is extremely low compared to other countries, such as Malaysia, where 70% of women work full-time jobs [

49]. Of course, most women in rural areas practice unpaid jobs, often in family and agricultural activities [

54], but female engineers who live in rural areas often enroll in school teaching and other unrelated engineering jobs [

12].

This study highlights the need for societal and institutional shifts to alleviate stressors faced by female engineers. Supported by public policies, advocacy for dual-earning couples can help normalize shared family responsibilities. For example, offering employer-sponsored mentorship programs for women in engineering could shift societal attitudes while providing practical solutions for work–family conflict.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

This snapshot survey examined the WFC experienced by female engineering employees in a Yemeni conservative society. The findings of this study revealed that the social traditions prevalent in conservative societies have a significant and negative impact on achieving a balance between family and work responsibilities. Various social issues related to female engineers, such as the relationship between marriage opportunities and the engineering profession, marriage and job opportunities, and the impact of marriage on job continuity and resignation, are well-established in Yemeni society. The prevailing social beliefs strongly discourage female employment in Yemen, particularly for married women. In Yemen, marriage is considered a permanent occupation for women, as dictated by religious laws and social norms. Consequently, husbands hold full authority as guardians over their wives and have the final say in whether they should pursue employment.

Engineering job opportunities in Yemen have eventually decreased due to the political crisis and economic decline. In the predominantly male-dominated engineering profession, managers tend to assign light-duty and office-based roles to female engineers as part of social respect and appreciation for women in Yemen. Consequently, a significant number of female engineering graduates either remain unemployed or find employment in the commercial, public, and education sectors, with only a few entering the industrial sector. It is worth noting that the survey findings indicated that all female engineers working in the industrial and construction sectors are unmarried.

The study findings reveal that female engineers in Yemen earn an average wage of USD 145 per month, which is 3.822 times lower than their male counterparts. Men engineers generally have more freedom of movement and a wide range of job tasks than females. Additionally, male engineers are more likely to accept engineering jobs that involve heavy duties, specific fields, and long hours. The high fertility rate among Yemeni women often leads to frequent leaves and absences from the workplace. Females also face limitations of work pressures, relocations, night shifts, and movement. To promote a better work–family balance, the study suggests that organizations should offer more workplace flexibility, such as flexible attendance and early leave policies, opportunities for remote work, and online task tracking. Low wages also play a significant role in magnifying WFC. It is important to note that sexual harassment is considered a criminal act under Yemeni law and is not prevalent as a societal behavior. However, its impact on female workers in Yemeni conservative society is still present, albeit to a lesser extent.

The study concludes that addressing work–family conflict requires systemic changes at multiple levels. Flexible workplace policies, public awareness campaigns, and professional organizations’ support can empower female engineers and challenge negative cultural norms. This research offers a foundation for long-term societal transformation by creating pathways for policy advocacy and education.

The following recommendations are derived from the research work:

It is essential for society, including families, to recognize and support dual-earning couples to increase their financial income.

Husbands should actively support their wives’ education and career aspirations.

Families should offer more flexibility and freedom to girls’ movement, enabling them to participate in public and private job sectors.

Employed women should effectively balance their professional duties, family responsibilities, and social commitments.

Society should implement policies that alleviate the pressure on women in the workforce while valuing and supporting the concept of dual-earning couples to enhance family income.

Highly educated females should be provided with ample job opportunities to enable their active participation in the economic development of both their families and the country.

Women should not succumb to societal expectations and strive for greater social recognition and respect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.G. and M.A.A.; methodology, A.M.G., L.A. and M.A.A.; software, H.A.A.-n., H.A.H. and S.M.; validation, A.M.G., M.A.A. and S.M.; formal analysis, A.M.G., M.A.A. and S.M.; investigation, M.A.A.; resources, L.A., H.A.A.-n. and H.A.H.; data curation, L.A., H.A.A.-n., M.A.A., H.A.H. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.G. and M.A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.M.G., L.A., H.A.A.-n., M.A.A., H.A.H. and S.M.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, A.M.G. and M.A.A.; project administration, L.A. and H.A.A.-n.; funding acquisition, A.M.G. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Alfaisal University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Before the study, ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Alfaisal University (Approval Code: IRB- 20417, Approval Date: 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Office of Research and Graduate Studies at Alfaisal University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barclay, K.; Carr, R.; Elliot, R.; Hughes, A. Introduction: Gender and Generations: Women and life cycles. Women’s Hist. Rev. 2011, 20, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jeffrey Hill, E.; Jacob, J.I.; Shannon, L.L.; Brennan, R.T.; Blanchard, V.L.; Martinengo, G. Exploring the relationship of workplace flexibility, gender, and life stage to family-to-work conflict, and stress and burnout. Community Work. Fam. 2008, 11, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhate, B.; Hirudayaraj, M.; Dirani, K.; Barhate, R.; Abadi, M. Career disruptions of married women in India: An exploratory investigation. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2021, 24, 401–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khursheed, A.; Mustafa, F.; Arshad, I.; Gill, S. Work-Family Conflict among Married Female Professionals in Pakistan. Manag. Stud. Econ. Syst. (MSES) 2019, 4, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, S. Perceptions of work-family conflict among married female professionals in Hong Kong. Pers. Rev. 2003, 32, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.A. The Work–Family Conflict: Evidence from the Recent Decade and Lines of Future Research. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2021, 42, S4–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajadhyaksha, U.; Korabik, K.; Lero, D.S.; Zugec, L.; Hammer, L.B.; Beham, B. The work-family interface around the world: Implications and recommendations for policy and practice. Organ. Dyn. 2020, 49, 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S. “Doing Men’s Jobs”: A Commentary on Work–Life Balance Issues Among Women in Engineering and Technology. Metamorphosis 2019, 18, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesiek, B.K.; Buswell, N.T.; Nittala, S. Performing at the Boundaries: Narratives of Early Career Engineering Practice. Eng. Stud. 2021, 13, 86–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göksel, I. Female labor force participation in Turkey: The role of conservatism. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2013, 41, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civettini, N.H.; Glass, J. The impact of religious conservatism on men’s work and family involvement. Gend. Soc. 2008, 22, 172–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalnour, H.; Abdulkhaliq, L.; Ghaleb, A.M.; Amrani, M.A.; Alduais, F. Challenges to Female Engineers’ Employment in the Conservative and Unstable Society of Taiz State, Yemen: A Survey Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Alawi, A.I.; Al-Saffar, E.; AlmohammedSaleh, Z.H.; Alotaibi, H.; Al-Alawi, E.I. A study of the effects of work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and work-life balance on Saudi female teachers’ performance in the public education sector with job satisfaction as a moderator. J. Int. Women’s Stud. 2021, 22, 486–503. [Google Scholar]

- Eshak, E.S.; Elkhateeb, A.S.; Abdellatif, O.K.; Hassan, E.E.; Mohamed, E.S.; Ghazawy, E.R.; Emam, S.A.; Mahfouz, E.M. Antecedents of work–family conflict among Egyptian civil workers. J. Public Health 2023, 31, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latief, O.K.A.E.; Eshak, E.S.; Mahfouz, E.M.; Iso, H.; Yatsuya, H.; Sameh, E.M.; Ghazawy, E.R.; Baba, S.; Emam, S.A.; El-Khateeb, A.S.; et al. A comparative study of the work-family conflicts prevalence, their sociodemographic, family, and work attributes, and their relation to the self-reported health status in Japanese and Egyptian civil workers. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.S. Identifying Barriers to Career Progression for Women in Science: Is COVID-19 Creating New Challenges? Trends Parasitol. 2020, 36, 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffenaud, A.; Unruh, L.; Fottler, M.; Liu, A.X.; Andrews, D. A comparative analysis of work–family conflict among staff, managerial, and executive nurses. Nurs. Outlook 2020, 68, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukerman, D.; Leger, K.; Charles, S.T. Work-Family Spillover Stress Predicts Health Outcomes Across Two Decades. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, T.; Far, H.; Gardner, A. Barriers to career advancement for female engineers in Australia’s civil construction industry and recommended solutions. Aust. J. Civil Eng. 2019, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burleson, S.D.; Major, D.A.; Hu, X.; Shryock, K.J. Linking undergraduate professional identity development in engineering to major embeddedness and persistence. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 128, 103590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadaret, M.C.; Hartung, P.J.; Subich, L.M.; Weigold, I.K. Stereotype threat as a barrier to women entering engineering careers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 99, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, L.; Conroy, N.; Barr, W., II. What Late-Career and Retired Women Engineers Tell Us: Gender Challenges in Historical Context. Eng. Stud. 2019, 11, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewsri, N.; Tongthong, T. Professional Development of Female Engineers in the Thai Construction Industry. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 88, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushiva, P.; Joshi, C. Women’s Re-entry after a Career Break: Efficacy of Support Programs. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2020, 39, 849–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozahem, N.A.; Ghanem, C.M.; Hamieh, F.K.; Shoujaa, R.E. Women in engineering: A qualitative investigation of the contextual support and barriers to their career choice. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2019, 74, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Corona, N.; Calleja, A.C.A.; Segovia-Hernández, J.G.; Aristizábal-Marulanda, V. Latin American women in chemical engineering: Challenges and opportunities on process intensification in academia/research. Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 2022, 181, 109161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb, A.M.; Amrani, M.A.; Al Selwi, R.A.M.; Hebah, H.A.; Saeed, M.A.; Mejjaouli, S. Socioeconomic Status as a Predictor of the Academic Achievement of Engineering Students in Taiz State, Yemen. Societies 2024, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Hanafi, I. The Yemeni Civil War’s Impact on The Socio-Cultural Conditions of the People in Yemen. J. Tapis J. Teropong Aspir. Polit. Islam 2023, 19, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Asi, Y.M. Child Marriage and Female Genital Mutilation in the MENA Region; Arab Center Washington DC: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Female Genital Mutilation in the Middle East and North Africa; Report; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Situational Analysis of Women and Girls in the Middle East and North Africa: A Decade Review 2010–2020; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ammar, F.; Patchett, H.; Shamsan, S. A Gendered Crisis: Understanding the Experiences of Yemen’s War; Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies: Sana’a, Yemen, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zaghruri, A.H.; Saeed, M.A.; Amrani, M.A. The Impact of Social Media on the Educational Attainment of Engineering Students under Conflict and Siege Conditions at Taiz City, Yemen. Al-Saeed Univ. J. Appl. Sci. 2024, 7, 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Amrani, M.A.; Al-Tayar, B.; Saeed, M.A.; Ghaleb, M.A.; Hebah, H.A.; Abdalnour, H. Barriers to the Effective Use of Technology in Higher Education Institutions in Yemen: A Case Study of Engineering Colleges. Albaydha Univ. J. 2023, 5, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manea, E. Women’s Rights in the Middle East and North Africa 2010—Yemen; Freedom House: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, M.C.; Brooks, J.S.; Mutohar, A.; Taufiq, I. Principals as socio-religious curators: Progressive and conservative approaches in Islamic schools. J. Educ. Adm. 2020, 58, 677–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edis, T. Modern science and conservative Islam: An uneasy relationship. Sci. Educ. 2009, 18, 885–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubaker, M.; Adam-Bagley, C. Arab Culture and Organisational Context in Work-Life Balance Practice for Men and Women: A Case Study from Gaza, Palestine. Societies 2024, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Alhareth, Y.; Al Alhareth, Y.; Al Dighrir, I. Review of women and society in Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 3, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL Smadi, A.N.; Amaran, S.; Abugabah, A.; Alqudah, N. An examination of the mediating effect of Islamic Work Ethic (IWE) on the relationship between job satisfaction and job performance in Arab work environment. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2023, 23, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraimi, A.A.; Shelke, A. Impact of Job Stress on Job Satisfaction for Nursing Staff: A Survey in Healthcare Services in Yemen; Research Square Platform LLC: Durham, NC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan Priyanka, T.; Akter Mily, M.; Asadujjaman, M.; Arani, M.; Billal, M.M. Impacts of work-family role conflict on job and life satisfaction: A comparative study among doctors, engineers and university teachers. PSU Res. Rev. 2024, 8, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.E.; Costello, S.B.; Chowdhury, S. Achieving gender balance in engineering: Examining the reasons for women’s intent to leave the profession. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 04022035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, R. Work and family identities and engineering identity. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 107, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]