Abstract

Research has highlighted racial and socioeconomic disparities for families in child welfare, with calls to address inequities through trainings and structural change. However, few measures have been developed to assess the recognition of racial and class biases among child welfare practitioners, one key step in addressing implicit biases and reducing racial disparities. While the Families First Prevention Services Act has prioritized evidence-based practices, it is crucial to ensure that practitioners are culturally responsive. This study developed and piloted the Race and Class Bias in Child Welfare Scale to measure the awareness of implicit and structural biases among child welfare practitioners. The development and validation of the Race and Class Bias in Child Welfare Scale included three parts: (1) scale development; (2) scale piloting using exploratory factor analysis; and (3) scale validation using confirmatory factor analysis. Two main factors were identified that explained 68.05% of the total variance; eight of the nine items loaded onto the two factors. Items on the first factor reflected implicit bias recognition, and items on the second factor reflected structural bias. Preliminary findings suggest that a two-factor scale presents good internal reliability and validity. As the Family First Preservation Services Act continues to prioritize evidence-based practices, it is important to consider the cultural sensitivity and responsiveness of providers administering them.

1. Introduction

Decades of research on racial and class disparities in child welfare have led to calls to advance racial equity and for support for underserved communities through executive orders, agency policy, and movements, such as the upEND movement to abolish the child welfare system []. Indeed, national studies have found that one in two Black children will be referred to child protective services by the time they reach their 18th birthday [], a rate that is 3.1 times higher than White children []. Disproportionate numbers of Black children are also removed from their homes and placed into foster care []. In fact, roughly 23% of children in foster care are Black [], while Black children represent only 14% of the child population in the United States [].

In light of the empirical evidence highlighting disparities across child welfare decision points [], several explanations have emerged. For instance, some scholars recognize the role of structural racism engrained in systems and institutions []. Other scholars argue that families of color disproportionately face other risk factors, such as poverty, that contribute to maltreatment []. Considering the duration of disparities over time and the abundance across county and state child welfare systems, LaBrenz and colleagues conducted a grounded theory study in which a conceptual model emerged that included implicit biases, interpersonal biases, and institutional and structural biases, all of which contributed to disparities in child welfare decision-making []. Based on this model, strategies to address bias and improve equity need to be multifaceted and target biases at multiple levels.

Implicit bias refers to negative attitudes held about a group that may exist outside of an individual’s consciousness []. Implicit biases drive behaviors and decision-making []. Practitioners hold their own implicit biases, which in turn impact interpersonal dynamics when interacting with clients; these may be reinforced explicitly or implicitly by institutional policy and practice. Some potential solutions have been developed to address implicit bias, such as equity trainings, appointment of equity officers, and changes in policies []. However, few measures to date have been developed to assess interpersonal and institutional biases in child welfare. This is a notable gap, as practitioners conduct assessments and make recommendations across the span of a child welfare case, resulting in multiple decision points where biases may impact case outcomes.

In order to change implicit bias, personal reflections on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors are necessary []. Some measures have been developed previously to assess bias among professionals in non-child welfare settings, such as healthcare or education. For example, the Color-Blind Racial Attitudes Scale (CoBRAS) is a widely used tool to assess the awareness of racial privilege, institutional discrimination, and blatant racial issues []. The Implicit Association Test (IAT) is another commonly used tool that measures implicit bias based on the strength of associations an individual makes when classifying categories []. Additionally, tools have been developed to assess how practitioners work with clients. For example, the Multidimensional Cultural Humility Scale (MCHS) assesses whether a practitioner relates well with a client from a different background []. While these tools have been used across professions to measure implicit bias and practice, they do not assess potential biases in the unique judgments child welfare practitioners must make, such as assessing parenting and parent–child interactions. Broader items on existing scales related to healthcare or other systems may not be as indicative of bias and the recognition of bias when making decisions about child maltreatment.

2. Current Study

While there is a clear need to address disproportionality in the child welfare system, the national focus has not been on addressing implicit bias. Rather, the child welfare field has been intensely focused on evidence-based practices to reduce entry into foster care, without focusing on specific racial/ethnic groups. Indeed, the clearinghouses take a color-blind approach when rating interventions. This also aligns with color-blind approaches several child welfare jurisdictions take in their assessment and decision-making processes, some of which have been critiqued and may warrant further research [,]. The passage of the Families First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) requires states to use evidence-based practices as a means to prevent children from entering the child welfare system by providing family support []. The focus on evidence-based practices is problematic in addressing disproportionality and implicit bias for two primary reasons. First, the rigid definition of evidence-based practices results in the exclusion of programs that are community-based and/or appropriate for racial and ethnic minority families [,]. In fact, in Wells and colleagues’ review of evidence-based practices in child welfare, they concluded that several interventions had no mention of their impact on diverse racial/ethnic groups, and among the few that did, studies often reported outcomes by client race/ethnicity instead of evaluating programs that were developed for specific racial, ethnic, or cultural groups []. The color-blind approach has been found in other research to increase discrimination and racism [,].

Additionally, evidence from the medical field suggests that using evidence-based interventions does not reduce implicit bias []. As much of the focus in evidence-based interventions is on fidelity to standardized protocols and procedures, there is less focus on the cultural responsiveness of individuals implementing interventions and how their attitudes, values, and biases may impact service delivery and effectiveness. This is a notable gap, as prior studies have found that worker bias contributes to racial disparities and inequities in the decision-making processes of child welfare professionals [,].

Given the need to recognize implicit bias to address disproportionality and the gap identified in validated measures of racial and class biases in child welfare, the main goal of this study was to develop and pilot a scale to assess racial and class biases among child welfare practitioners. There were three main stages of the study: (1) scale development; (2) scale pilot with exploratory factor analysis; and (3) factor structure validation using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), all of which contributed to the development, pilot, and validation of the Racial Class Bias Scale (RCBS).

3. Method

Data for this study came from a larger mixed methods evaluation of a multi-year, multi-site intervention to increase family engagement and improve permanency outcomes for children and youths in foster care in a large Southern state. The first stage of this study used data from a series of focus groups that were conducted in April 2019 with child welfare practitioners and other stakeholders (e.g., judges, mental health clinicians, researchers) as part of a statewide conference on child welfare and family engagement. The second and third stages of the study used quantitative data from surveys that were administered to child welfare practitioners who registered for at least one training of the intervention that was developed.

3.1. Stage One: Scale Development

The initial scale development was spearheaded by a research team that included three licensed social workers who also held PhDs and had experience in social work research. As part of the launch of the larger project, the research team convened a conference for child welfare stakeholders across the state. The conference was promoted through the lead author’s institutional social media and was sent to the public child welfare agency leadership, as well as other key organizations involved in child welfare, such as Court Appointed Special Advocates and other statewide non-profits that served children or families involved in child welfare. A total of 71 individuals attended the conference and, in the afternoon, were divided into groups of approximately eight to participate in focus groups (n = 9 total) to explore root causes of child welfare involvement. The research team utilized the registration list to ensure diverse representation at each table where focus groups were conducted. For example, at least one public child welfare employee was assigned to each table. In total, stakeholders who participated in focus groups included professionals from the public child welfare agency (n = 9), court-appointed special advocates (n = 11), court representatives (n = 1), child placing agency employees (n = 11), other providers who support foster youths (n = 10), other professionals (n = 23), birth parents (n = 3), foster parents (n = 1), and former foster youths (n = 2). Other professionals included project staff, policy advocates, and private philanthropic groups.

A member of the research team or volunteers (other staff at the lead author’s institution and/or doctoral students) sat at each table to facilitate the focus group and had a list of semi-structured focus group questions to guide discussion. All facilitators attended a one-hour training prior to facilitating the focus group. Focus groups lasted between 45 and 60 min, and extensive notes were taken by the facilitator. After the conference, all facilitators convened and pooled notes. The second author on this paper combined notes and, together with the research team, identified key themes and concepts that emerged.

Based on the root cause analysis and applied thematic analysis of the notes from the focus groups, two main themes were identified: (1) child welfare outcomes are negatively impacted by racial biases, and (2) child welfare outcomes are negatively impacted by class biases. The project team consulted with the project’s funder and technical assistance providers as a form of member checking and confirmed these two root causes as key targets for the larger project’s interventions. Two members of the research team with master’s degrees in social work conducted independent literature reviews of measures for race and class biases in human service professions. The two researchers then met to review each scale to assess the fit with the present study and adaptability for the target population. Two scales were identified as potential measures for the study, although neither included child welfare items: the Multicultural Humility Scale (MCHS) [] and the Color-Blind Racial Attitudes Scale (CoBRAS) []. These scales were presented to the other members of the research team, who identified which items could be used or adapted for the present study. Given the lack of child welfare-specific scales, the research team developed nine additional items specific to racial and class biases in child welfare. Based on the literature review, five items were developed that targeted implicit and interpersonal biases (e.g., aligned more with MCHS), and four items were developed that targeted institutional and structural biases (e.g., more aligned with CoBRAS). These domains align with prior research that identified implicit, interpersonal, institutional, and structural biases that impact decision-making and subsequent disparities in child welfare []. An overview of items used in this study are included in Table 1. Each scale item was measured on a six-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Table 1.

Items included that were related to race and class biases.

3.2. Stage Two: Exploratory Factor Analysis with a Subset of Child Welfare Practitioners

After the initial scale was developed, the second stage of the project consisted of piloting the scale among a sample of child welfare practitioners. Data for stage two of the project came from child welfare practitioners who registered for the Texas Permanency Outcomes Project (TXPOP-PM) Practice Model training. TXPOP-PM training was conducted at three sites in a large Southern state. Site A was at a child placing agency (CPA) in a large, diverse metropolitan city. Site B was at a CPA located along the U.S.–Mexico border. Site C was a privatized child protection agency located in a large geographic region that included several rural counties. Practitioners and leadership at each site, as well as caregivers who fostered children through each CPA and other child welfare stakeholders in the regions, including public child protective service practitioners, participated in the TXPOP-PM. Training was divided into professional trainings (practitioners and leadership) and caregiving trainings (for non-relative and kinship caregivers). All individuals who registered for TXPOP-PM were sent a pre-survey to complete prior to any exposure to the training. The professional pre-survey included subscales from CoBRAS, a subscale from MCHS, measures related to family engagement, and the RC Bias scale. A total of 152 practitioners completed the pre-survey (95.6% response rate). The researchers conducted a principal components factor analysis to explore the structure of the Race Class Bias scale (RCB) among the sample. Varimax rotation was used, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin MSA was conducted to observe the fit of the identified factor structure. All analyses were conducted in Stata SE, version 16.1, and significance was set at p < 0.05.

3.3. Stage Three: Piloting the Scale with Child Welfare Academy Participants

After the exploratory factor analysis, the third and final stage of the study consisted of confirming the structure of the data among a larger sample. Data for the third stage of the study came from a sample of child welfare practitioners and stakeholders who participated in the statewide Child Welfare Academy. As individuals enrolled online, they were asked to complete a pre-survey prior to beginning any of the coursework. A total of n = 380 child welfare stakeholders completed the pre-survey that included the CoBRAS subscales, MCHS subscale, RC Bias measure, and other measures related to family engagement (response rate = 67.14%). A CFA was conducted with a two-factor measurement model (based on the number of components identified in stage two). Model fit was assessed by calculating the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR). All analyses were conducted in Stata, version 16.1, and significance was set at p < 0.05.

4. Results

Results are first presented for the principal components analysis conducted to pilot the measure among professionals who registered for TXPOP-PM and then for the CFA conducted on the sample of professionals who enrolled in the Child Welfare Academy. Table 2 displays sample demographics for stages two and three of the project.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of EFA and CFA samples.

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis: Principal Components Analysis

In the initial pilot of the measure, the scale was administered to n = 152 child welfare practitioners who worked at a child placing agency, implementing a practice model to improve family engagement. As part of the program, practitioners completed a pre-survey. A principal components factor analysis was conducted to identify the underlying structure of the measure. In the initial factor analysis, eight of the nine items loaded onto two factors. Table 3 displays the factor loadings and the KMO. As seen in Table 3, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin MSA was 0.82, indicating adequate sampling. The two-factor solution accounted for 68.05% of the variance. Factor 1 included five items that conceptually represented the recognition of institutional or structural biases. Factor 2 consisted of three items that reflected individual practices of critical humility. One item, “I have my own biases that impact the way I see a case”, did not load onto either of the factors.

Table 3.

ML Varimax items and loadings (n = 152).

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Validation

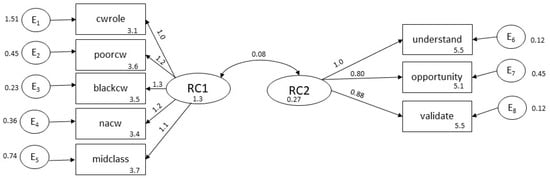

In the next phase of the project, the research team administered the scale to n = 380 practitioners across a large Southern state who enrolled in a Child Welfare Academy to provide training on recognizing and addressing racial and class biases in child welfare. A CFA using a structural equation measurement model was conducted. Figure 1 displays the final CFA model with factor loadings and coefficients. All five items from the EFA significantly loaded onto Factor 1, and all three items from the EFA significantly loaded onto Factor 2. Model fit was adequate, with an RMSEA of 0.06, a CFI of 0.98, and a SRMR of 0.03.

Figure 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the RC Bias Scale. Note: RMSEA = 0.06; CFI = 0.98; SRMR = 0.03.

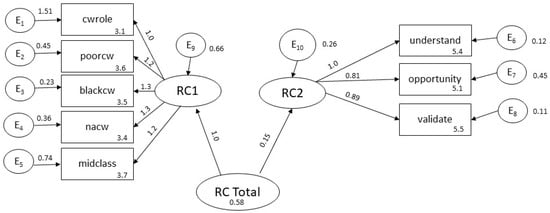

Based on the correlations between the two factors, a higher-order CFA was conducted to test for a higher-factor solution. Figure 2 presents the higher-factor solution, which displayed good model fit (RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.03).

Figure 2.

Higher-factor solution.

4.3. Convergent Validity Testing

In addition, correlations between the RC Bias Scale and CoBRAS were conducted to examine convergent validity. Factor 1 of the RC Bias Scale was significantly correlated with both CoBRAS Factor 1 (r2 = −0.15, p < 0.001) and CoBRAS Factor 3 (r2 = −0.19, p < 0.001), and Factor 2 of the RC Bias Scale was also significantly correlated with both CoBRAS Factor 1 (r2 = −0.68, p < 0.001) and CoBRAS Factor 3 (r2 = −0.36, p < 0.001).

5. Discussion

This study developed and piloted the RC Bias Scale (RCBS) to assess attitudes and the recognition of racial and class biases among child welfare practitioners. Findings suggest the RCBS is a useful tool for assessing child welfare caseworker bias. A principal components analysis refined the measure, and a confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated that the items significantly loaded onto the two scale domains. Additionally, in a supplementary analysis, the RCBS demonstrated strong convergent validity with the COBRAS, suggesting that it accurately assesses implicit bias.

RCBS contains two domains: (1) perceptions of the child welfare system and (2) personal beliefs and behaviors. The first domain contains five questions that relate to a child welfare professional’s perception of the following items: (1) child welfare’s role in perpetuating white supremacy; (2) treatment of the families living in poverty; (3) treatment of Black families; (4) treatment of Native American families; and (5) whether families are all held to middle-class parenting standards. In the initial development of this scale, focus group participants specifically identified root causes of disparate treatment based on class and race. This domain ultimately captured those root causes. The second domain addresses the child welfare professional’s personal beliefs based on three items assessing the importance of: (1) understanding a family’s cultural background; (2) seeking opportunities to learn about differences and create new relationships; and (3) honoring the family’s cultural background. Notably, one item (“I have my own biases that impact the way I see a case”) did not load onto either factor. It is possible that the wording of this particular item resulted in respondents answering it differently than the other items. Indeed, as respondents went through trainings, it is possible that they were more aware of their own implicit biases and were more willing to acknowledge these potential biases. More research is needed to understand how this item might relate to the factors and other items developed on the RCBS.

Given the need to address disproportionality in the child welfare system, understanding caseworker implicit bias is critical. Child welfare workers make critical decisions that impact families for their lifetime []. The RCBS is a measurement tool that specifically looks at bias within the child welfare system rather than broader societal beliefs. Utilizing the RCBS as a measurement tool coupled with diversity and equity trainings could assist in assessing change in a caseworker’s understanding of their biases. Moreover, findings from this study align with other research that has called for addressing implicit biases among practitioners throughout decision-making processes [,]. Tools such as RCBS could be used to assess the understanding of implicit and structural biases among practitioners who implement evidence-based practices in child welfare settings to ensure cultural responsiveness. For example, the RCBS could be used in conjunction with risk assessments and other tools as practitioners investigate cases and make decisions related to substantiation and removals.

6. Limitations

Although this study contributes a novel scale to assess bias among child welfare workers, there are some limitations to note. First, although we piloted the RCBS on two samples of child welfare workers, all individuals who participated agreed to receive TXPOP training. Participation in the Child Welfare Academy was voluntary; participation in the practice model was voluntary for some stakeholders (e.g., public child welfare agency practitioners), but it was required for practitioners at the child placing agencies selected as sites for the intervention. It is possible that there was selection bias in who participated in the trainings that may have also introduced some bias into the results. Furthermore, it is possible that the two samples of workers are not necessarily representative of all child welfare workers in the particular state. Second, all child welfare workers in the two samples worked in the same large state. Although the sample was racially/ethnically diverse, future research could examine the factor structure of the scale among a larger, more geographically diverse sample. Additionally, we only tested internal validity in this initial measurement model of the RCBS. Future research is needed to examine predictive validity. Future research is also needed to examine how scores on the RCBS may change after participation in interventions, such as TXPOP, that target raising the awareness of racial bias. Finally, these trainings were implemented between 2021 and 2023; it is worth noting that there has been an increased focus on addressing implicit and structural biases during these years, and the trainings also occurred during the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and aftermath. As such, contextual factors and social desirability bias related to equity and implicit bias may have impacted findings.

7. Conclusions

The passage of the Families First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) in 2018 initially spurred conversations about the potential for FFPSA to reduce racial equity. Proponents noted that the shift to providing services for families was an avenue for engaging communities in prevention efforts, supporting kinship families, and focusing on the needs of families rather than removing children, all of which have been championed as potential strategies for reducing racial disparities in child welfare []. However, discourse shifted as the policy was implemented, and “evidence-based” interventions were defined. The majority of funding through FFPSA is directed to evidence-based interventions. Child welfare advocates and scholars note that the rigid definition of evidence-based practice results in the exclusion of programs that are community-based and/or appropriate for racial and ethnic minority families [,,]. In fact, the lack of interventions that qualify as evidence-based under FFPSA has resulted in a limited roll-out of programs for families [].

Regardless of whether a caseworker is using an evidence-based practice, implicit bias is present. Evidence-based practices do not eliminate implicit bias. Thus, all professionals still need training and support to understand and address biases []. There is a clear disproportionate number of Black families separated by child welfare interventions, and evidence-based programs will not address that inequity without a deeper understanding of bias. The RCBS is a tool the child welfare field can use to help workers self-reflect and ultimately change behaviors. Furthermore, the RCBS can track awareness of structural biases, which can help identify the readiness and preparedness of practitioners to advocate for economic and concrete supports; this can also include advocacy for larger structural changes to support families historically excluded and/or marginalized by child welfare systems.

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.F., C.A.L., A.W. and L.M.; formal analysis, C.A.L. and A.W.; investigation, A.W.; data curation, C.A.L. and A.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F., C.A.L. and A.W.; writing—review and editing, L.M.; supervision, M.F. and L.M.; project administration, M.F.; funding acquisition, M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was developed from the Texas Permanency Outcomes Project which was funded by the Children’s Bureau, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, under grant #90CO1138.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the institutional review board considering the study to be program evaluation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset presented in this article is not readily available because it is part of an on-going project. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the lead author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the sites involved in the Texas Permanency Outcomes Project as well as child welfare staff who completed surveys.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Children’s Bureau.

References

- Dettlaff, A.J.; Boyd, R. Racial Disproportionality and Disparities in the Child Welfare System: Why Do They Exist, and What Can Be Done to Address Them? Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2020, 692, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, F.; Wakefield, S.; Healy, K.; Wildeman, C. Contact with Child Protective Services is pervasive but unequally distributed by race and ethnicity in large US counties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2106272118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, A.L.; Boamah, D.A.; Warfel, E.T.; Griffiths, A.; Roehm, D. Ending racial disproportionality in child welfare: A systematic review. Child. Soc. 2024, 38, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The AFCARS Report. Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. 2023. Available online: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Kids Count Data Center. Child Population by Race and Ethnicity in United States. Annie E. Casey Foundation. 2022. Available online: https://datacenter.aecf.org/data/tables/103-child-population-by-race-and-ethnicity#detailed/1/any/false/1095,870,573,869,36/68,69,67,12,70,66,71,72/423,424 (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Harris, M.S.; Hackett, W. Decision points in child welfare: An action research model to address disproportionality. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2008, 30, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettlaff, A.J.; Weber, K.; Pendleton, M.; Boyd, R.; Bettencourt, B.; Burton, L. It is not a broken system, it is a system that needs to be broken: The upEND movement to abolish the child welfare system. J. Public Child. Welf. 2020, 14, 500–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, B.; Jones, D.; Chen, J.H.; Font, S. Poverty or Racism? A Re-Analysis of Briggs et al. 2022. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2024, 34, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBrenz, C.A.; Reyes-Quilodran, C.; Padilla-Medina, D.; Arevalo Contreras, M.; Cabrera Piñones, L. Deconstructing bias: The decision-making process among child protective service workers in Chile. Int. Soc. Work. 2023, 66, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forscher, P.S.; Lai, C.K.; Axt, J.R.; Ebersole, C.R.; Herman, M.; Devine, P.G.; Nosek, B.A. A meta-analysis of procedures to change implicit measures. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 117, 522–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brondolo, E.; Kaur, A.; Seavey, R.; Flores, M. Anti-Racism Efforts in Healthcare: A Selective Review From a Social Cognitive Perspective. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2023, 10, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, K.H.; Desdune, J.; Johnson, T.R.; Green, K. Examining a community intervention to help White people understand race and racism and engage in anti-racist behaviours. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 33, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, H.A.; Lilly, R.L.; Duran, G.; Lee, R.M.; Browne, L. Construction and initial validation of the Color-Blind Racial Attitudes Scale (CoBRAS). J. Couns. Psychol. 2000, 47, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Brendl, M.; Cai, H.; Cvencek, D.; Dovidio, J.F.; Friese, M.; Hahn, A.; Hehman, E.; Hofmann, W.; Hughes, S.; et al. Best research practices for using the Implicit Association Test. Behav. Res. Methods 2022, 54, 1161–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, E.; Sperandio, K.R.; Mullen, P.R.; Tuazon, V.E. Development and Initial Testing of the Multidimensional Cultural Humility Scale. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2021, 54, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feely, M.; Bosk, E.A. That which is essential has been made invisible: The need to bring a structural risk perspective to reduce racial disproportionality in child welfare. Race Soc. Prob. 2021, 13, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.F.; Stapleton, L.; Kawakami, A.; Sivaraman, V.; Cheng, Y.; Qing, D.; Perer, A.; Holstein, K.; Wu, Z.S.; Zhu, H. How child welfare workers reduce racial disparities in algorithmic decisions. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human, Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 30 April–5 May 2022; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Family First Prevention Services Act. Public Law 115–123. 2017. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1892 (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Burnson, C. Family First Evidence Standards Risk Worsening Racial Inequities in Child Welfare. Evident Change. 2021. Available online: https://evidentchange.org/blog/family-first-evidence-standards-risk-worsening-racial-inequities-child-welfare/ (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Bonnick, D.; Grutza, J.; Scolnick, K. Family First Act’s Standards Are Not Culturally Inclusive. The Imprint. 2021. Available online: https://imprintnews.org/child-welfare-2/family-first-act-standards-not-culturally-inclusive/53095 (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Wells, S.J.; Merritt, L.M.; Briggs, H.E. Bias, racism and evidence-based practice: The case for more focused development of the child welfare evidence base. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2009, 31, 1160–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaut, V.C.; Thomas, K.M.; Hurd, K.; Romano, C.A. Do Color Blindness and Multiculturalism Remedy or Foster Discrimination and Racism? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 27, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelin, J.R.; Siraj, D.S.; Victor, R.; Kotadia, S.; Maldonado, Y.A. The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognize and Mitigate It. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220 (Suppl. S2), S62–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauritzen, C.; Vis, S.A.; Fossum, S. Factors that determine decision making in child protection investigations: A review of the literature. Child. Fam. Soc. Work. 2018, 23, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.; Sinha, A. Addressing gaps in culturally responsive mental health interventions in the Title IV-E prevention services clearinghouse. Clin. Soc. Work. J. 2023, 52, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.; Riley, N. Five Years on, the Family First Act Has Failed in Its Aims. The Hill. 2023. Available online: https://thehill.com/opinion/civil-rights/3951473-five-years-on-the-family-first-act-has-failed-in-its-aims/ (accessed on 4 June 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).