Abstract

Among children with special needs, those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are more susceptible to school bullying, due to communication challenges. In this study, the severity and types of school bullying, mainly physical, verbal, and social, experienced by children with ASD were identified and assessed from their mothers’ perspectives in Jordan. Additionally, the mothers’ levels of agreement with a set of anti-bullying interventions targeted at preventing bullying or attenuating its adverse consequences on children with ASD were evaluated. The results revealed that verbal and physical bullying were the most common types of school bullying experienced by children with ASD. Furthermore, the frequency of bullying has not been correlated to gender or school type; however, children in primary school experienced a higher frequency of school bullying. The results also revealed a set of proposed anti-bullying interventions that received a high level of agreement from the mothers. These interventions include arranging for various training sessions and programs targeted to children with ASD and their mothers to guide them on handling bullying and assigning specialists at schools to evaluate, monitor, and prevent bullying behaviors and support bullied students. Such interventions are considered promising opportunities for addressing school bullying among children with ASD.

1. Introduction

Bullying is a persistent problem and has attracted significant research in recent years, fueled by technological advancements and the emergence of cyberbullying. Bullying is generally defined as aggressive behavior marked by intentionality, repetition, and a power imbalance between the bullies and the bullied victims [1,2,3,4], and it occurs in various forms: physically, verbally, socially, through property damage, or sexually. Cyberbullying is a recent dimension of bullying that emerged due to advances in digital communication platforms [5].

School bullying is widely recognized as the most prevalent form of bullying and has received significant research attention. However, bullying among adults can occur in various settings, including workplaces, recreation centers, support groups, senior centers, events, and online platforms [6]. The severity of school bullying is evident by its global impact on millions of students, with prevalence rates ranging from 10% to 45%, as reported by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [7]. School bullying creates unhealthy school environments and has severe consequences on students’ academic performance, social skills, and mental health, and can lead to suicidal ideation, self-harm, anxiety, and depression [8].

The negative consequences of school bullying have become more severe for children with special needs, who are often vulnerable to bullying due to challenges in social and emotional communication [9,10]. For instance, children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a condition characterized by limitations in communication and social interaction, face challenges in establishing positive peer relationships and social connections [11,12]. Consequently, they experience more frequent and severe bullying than their peers with intellectual disability or typical development [13]. A recent study found that 46% of a sample of 8-year-old children with ASD in Finland experienced bullying victimization compared to 2% in the sample with no ASD [14].

Bullying against children with ASD takes different forms; for instance, physical, social, verbal, electronic and property-related [4,15,16,17], and its influence on the children is paramount, resulting in school rejection and psychological distress [18]. These consequences amplify the severity of ASD, placing children at elevated risk of bullying victimization. A study conducted in Turkey found that children with ASD are more likely to experience verbal and emotional bullying, with a positive correlation observed between the severity of ASD and bullying incidents [19].

The global recognition of bullying has led to the development of anti-bullying laws. The UNESCO report (2021) emphasizes the importance of equal opportunities for children with disabilities in school activities and representation on management committees [20]. Bullying prevention requires collaboration among various stakeholders, including governmental bodies, educators, medical professionals, parents, the community, schools, and health advisors [21,22]. Therapeutic and preventive strategies include collaborative interventions, student-focused prevention programs, and initiatives promoting self-determination [23,24]. Essentially, parental involvement in bullying prevention programs can significantly reduce the consequences of school bullying by effectively reporting bullying incidences and addressing its consequences at home [25].

For children with ASD, comprehensive, multi-sided approaches are essential to prevent bullying on diverse educational grounds. For example, social skills strategies should target not only children with ASD but also their peers, academic support staff, and school environment [26]. Additionally, research highlights the potential benefits of involving parents in school-related activities; for instance, Zhang and Chen et al. conducted interviews with 16 parents of children with ASD in China and revealed that parents often handle bullying incidents independently and sometimes adopt concerned views regarding their children’s experiences [27]. Moreover, a recent study in Saudi Arabia demonstrated the importance of teacher–parent collaboration to enhance awareness of bullying against students with ASD and training sessions for parents on electronic tools for combating cyberbullying [28].

In Jordan, there is limited information available regarding the prevalence of ASD. However, it is estimated that approximately 10,000 children have been diagnosed with autism, based on a projected rate of 1 in 50 [29,30]. According to reports from the Jordanian Ministry of Education, nearly 339 students with ASD have been integrated into public schools [31]. According to the UNESCO report on school bullying in Arab states (2019), 41.1% of students reported they were bullied at least once in the past month, making the Middle East the region with the third-highest prevalence of bullying in the world. [32]. Al-Raqqad et al. have demonstrated the negative consequences of bullying on students’ academic achievement as per teachers’ perspective in Jordan [31], while Shaheen et al. highlighted the multifaceted factors for bullying among adolescents in Jordan and the need to develop strategies to combat bullying through these factors [33].

In adherence to the guidelines outlined in the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, numerous nations, including the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan as a pioneering advocate in this area, are progressively advancing towards including students with disabilities within mainstream educational and academic settings. To actualize this objective, these countries, with Jordan at the forefront, have formulated educational policies and strategic plans. Consequently, a surge in the enrollment of students with ASD in inclusive schools, particularly in Jordan, has been observed. Despite the prevailing enthusiasm for inclusive education for children with disabilities, concerns persist among educators and parents regarding potential challenges encountered by students due to their conditions. One prevalent issue is school bullying, affecting students both with and without disabilities. Bullying is characterized by an imbalance in physical and mental prowess between the perpetrator and the victim. Students with ASD are particularly vulnerable to peer bullying, due to their struggles with communication, social interaction, and various behavioral complexities. Thus, this study assumes significance as it delves into the prevalence of school bullying against students with ASD. To the best of our knowledge, studies in Jordan that have addressed bullying among students with ASD or explored their mothers’ perspectives on interventions to prevent or mitigate the effects of bullying are limited.

The social vulnerability and the socio-ecological models of bullying are considered the theoretical framework for this study. Social vulnerability theory presents individuals with ASD as more susceptible to bullying, due to their perceived or actual social weaknesses. The socio-ecological model of bullying views bullying as a complex interaction of individual, societal, communicational, and community factors, highlighting the multifaceted nature of bullying experienced by students with ASD.

By applying these theories, our study contributes to the educational field in several ways. First, it provides valuable empirical data on the prevalence and types of bullying faced by students with ASD in Jordan, an underrepresented area in the literature. Second, it highlights the perspectives of mothers, who are highly sensitive to their children’s needs and often first to notice signs of distress, offering unique insights into the challenges faced by children with ASD and making mothers’ insights particularly valuable. Third, this study proposes practical, evidence-based interventions that can be implemented in schools to reduce the negative impact and consequences of bullying for students with ASD. Finally, this study enlightens policymakers on the specific needs and vulnerabilities of students with ASD and develops targeted policies and programs to foster a safer and more inclusive school environment.

More specifically, this study aims to answer the following research questions: what are the frequency and most common types of school bullying experienced by students with ASD in Jordan, as reported by their mothers, and what are the mothers’ perspectives on effective anti-bullying interventions?

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants and Procedures

In this study, data were collected via a survey from 70 mothers of students with ASD using the snowball sampling technique [34]. The survey asked about the frequency of various forms of bullying the children experienced during their time at school across three dimensions: physical bullying and property damage, verbal bullying, and social bullying.

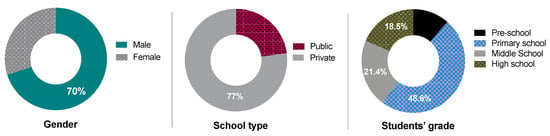

Furthermore, the mothers were asked about their level of agreement with a set of proposed anti-bullying interventions aimed at preventing school bullying or reducing its negative consequences on their children. The participating students attended both public and private schools at different educational stages. The demographic information regarding gender, school type, and students’ grades was gathered and is presented in Section 3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The demographic profile of children with ASD participating in the study.

2.2. Study Tool

The current study utilized a self-developed survey constructed through an extensive literature review [3,4,35,36].

The survey consists of three sections:

- Demographic information regarding the mothers and their children.

- The first domain consists of twenty-eight items divided into three dimensions: (a) direct bullying, consisting of physical and property destruction (11 items), and (b) indirect bullying, covering verbal dimension (9 items) and social dimension (8 items). This part aimed to estimate the frequency and types of school bullying experienced by students with ASD.

- The second domain consists of six proposed anti-bullying interventions aimed at preventing bullying or reducing its adverse effects on children with ASD, along with mothers’ agreement to these interventions (Table S1, Supporting Information).

2.3. Study Tool Validation

2.3.1. Face Validity

To ensure the face validity of the survey, a panel of five experts in special education reviewed the construct, clarity, and scale quality of the study tool, confirming its appropriateness for the research questions.

2.3.2. Construct Validity

The construct validity was assessed by piloting the survey with a group of mothers not included in the study sample to determine the strength and direction of the relationship between individual items and the overall construct of bullying experienced by students with ASD [37]. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between each item within the first (bullying dimensions) or second domain (anti-bullying interventions) and the total score of that domain was calculated. The statistical significance was estimated at an alpha level of less than 0.05.

2.3.3. Cronbach’s Alpha Test

Cronbach’s Alpha test was used to determine the internal consistency or reliability of the survey after it was piloted on a sample of 15 participants (excluded from the study sample) [38].

2.3.4. Correction Standard

The study sample’s vocabulary responses to the first domain (the bullying aspects) were obtained using a four-point Likert scale, with the following degrees of agreement: five or more times, three to four times, one to two times, and never. The scale was then expressed quantitatively, with each of the prior assertions assigned a score based on the following: five or more times = 4, three to four times = 3, one to two times = 2, never = 1, as given in Table 1.

Table 1.

The four-way Likert scale measurement for the first domain.

A four-point Likert scale was also used to obtain the study sample’s responses to the second domain (the anti-bullying initiatives), according to the following degrees of agreement: strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree. Then, this scale was expressed quantitatively, by giving each of the previous statements a score according to the following: strongly agree = 4, agree = 3, disagree = 2, strongly disagree = 1, and this is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Dividing the four-way Likert scale measurement for the second domain.

2.4. Assessing the Frequency and Types of School Bullying Experienced by Children with ASD, and Mothers’ Levels of Agreement with Anti-Bullying Initiatives

Based on the above measurements and degree of approval, the means, SDs, ranks, and significant level were estimated for the first domain, its bullying dimensions, and the individual items for each dimension, to assess the frequency, severity, and type of school bullying the children with ASD had experienced from the mothers’ perspectives. Similarly, the means, SDs, ranks, and significant levels were estimated for the second domain related to the anti-bullying initiatives and its items, to assess mothers’ levels of agreement with the proposed anti-bullying initiatives.

2.5. Assessing the Frequency of School Bullying across Gender, School Type, and Students’ Grades

The study examined the frequency of school bullying experienced by children with ASD, considering gender, school type, and grade to estimate the potential impacts of these variables by comparing the means and determining the significance of statistical differences.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS software, version 26, using the Cronbach alpha test for tool reliability assessment, Pearson correlation coefficient for association measurement, arithmetic means and standard deviations for central tendency and dispersion, and the independent sample t-test and one-way ANOVA for group comparison.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

Figure 1 illustrates the demographics of the children with ASD in terms of gender, school type, and student’ grades.

The demographics of the children with ASD are illustrated in Figure 1 in terms of gender, school type and students’ grades.

3.2. Validation Test Results

3.2.1. Construct Validity

The construct validity, measured by the correlation coefficients, helps determine the strength and direction of the relationship between individual items of each domain in the study tool and the overall bullying experienced by students with ASD. Higher correlation coefficients indicate stronger relationships and provide evidence of the tool’s validity, indicating that the items effectively measure the intended construct.

For the first domain (school bullying aspects), the Pearson correlation coefficients of the items indicate a strong correlation between these individual items and the total score of the domain, confirming good tool validity (Table 3). However, it is worth noting that item number 9 from the verbal bullying dimension and item number 5 from the social bullying dimension revealed a moderate and a weaker positive correlation, respectively. This suggests that these items may align less strongly with the overall domain.

Table 3.

Construct validity of the first domain, school bullying aspects. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

For the second domain (the anti-bullying initiatives), the Pearson correlation coefficients between the individual items within the second domain and the total score demonstrate a strong correlation between the items and the total score of the domain (Table 4). This means that higher scores on these individual items consistently align with higher total scores in their domain. Notably, the statistically significant correlations (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01) further confirm that the items effectively measure the intended aspects of school bullying, providing robust evidence of construct validity.

Table 4.

Construct validity of the second domain, anti-bullying initiatives. ** p < 0.01.

3.2.2. Cronbach’s Alpha Test

The stability coefficients for various domains and aspects of a survey on school bullying and anti-bullying initiatives indicate their internal consistency and reliability. Overall, the results indicate that most domains and dimensions of the study tool exhibit good-to-excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.692 to 0.911. The high reliability of the physical and verbal dimensions and the tool as a whole suggests that the survey items are effective and dependable in measuring the intended aspects of school bullying and anti-bullying initiatives (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the study tool domains and aspects.

3.3. Frequency and Severity of Various Forms of School Bullying

This study estimates the frequency and severity of multiple forms of bullying across three dimensions: physical and property damage, and verbal and social bullying. Each dimension is evaluated through specific bullying behaviors, ranked by their arithmetic mean (a measure of average frequency) and standard deviation (a measure of variability).

3.3.1. Physical Bullying and Property Damage

The dimension of physical bullying and property damage reveals that the most significant form of bullying reported is the taking of property without permission, with a high arithmetic mean of 3.21 and the lowest standard deviation of 0.94, indicating a high frequency and relatively consistent reporting among students. Other significant forms include obstructing and pushing with the intent to cause harm (mean = 3.12, SD = 1.02), and physical forcing to perform unwanted tasks (mean = 3.06, SD = 0.96), both rated high significances. Medium significance items, such as being physically attacked (mean = 2.62, SD = 1.15) and intentional property destruction (mean = 2.92, SD = 1.10), show moderate frequency but with more significant variability. Overall, this dimension has an average mean score of 2.93, indicating a medium level of physical bullying and property damage reported by students (Table 6).

Table 6.

Means and SDs of the various forms of school bullying that student with ASD experienced.

3.3.2. Verbal Bullying

Verbal bullying shows a high overall frequency, with a mean score of 3.05. The most notable behavior in this dimension is using offensive names, which is significantly high (mean = 3.54, SD = 0.84). Other highly prevalent verbal bullying behaviors include making fun of stereotypical behavior (mean = 3.05, SD = 1.01), mocking linguistic delays (mean = 3.14, SD = 1.03), and making fun of the need for support (mean = 3.14, SD = 1.03). These high means reflect a widespread issue, despite variability in how often these behaviors occur. Verbal threats of physical harm (mean = 2.72, SD = 1.07) and offensive comments (mean = 2.95, SD = 1.01) are reported with medium frequency, indicating these forms are also common but less so than the highly frequent behaviors (Table 6).

3.3.3. Social Bullying

The highest-ranked behavior is intentional exclusion from activities (mean = 3.28, SD = 0.79), reflecting a high frequency and consistency among students. Making fun of appearance (mean = 3.18, SD = 1.08) and spreading false rumors (mean = 2.92, SD = 1.14) are also highly reported. Other medium-significance behaviors include ignoring or excluding from friend groups (mean = 2.35, SD = 1.12) and refusal to communicate or play (mean = 2.16, SD = 1.14), which show a lower frequency and higher variability (Table 6).

3.4. Proposed Anti-Bullying Interventions

From a mother’s perspective, the interventions are ranked based on their effectiveness (means, SD).

3.4.1. High-Significance Interventions

One of the most impactful interventions, with a high significance level based on the mothers’ perspective, is the implementation of training programs specifically designed for students with ASD on handling bullying, with an arithmetic mean of 3.44 and a standard deviation of 0.84. The second-ranked intervention, involving the appointment of school employees to monitor and prevent bullying and support affected students, also shows a high significance level, with a mean score of 3.38 and a low standard deviation of 0.83 (Table 7). The third high-significance intervention focuses on training programs for all parents to educate them on parenting strategies that can reduce the incidence of bullying with a mean of 3.20 and an SD of 0.95.

Table 7.

Means and SDs of the significance of the proposed anti-bullying initiatives in schools against children with ADS from mothers’ perspective.

3.4.2. Medium-Significance Interventions

The results revealed that the development and implementation of clear policies regarding bullying rank fourth, with a mean score of 2.76 and SD of 1.06 (Table 7). The fifth-ranked intervention emphasizes the importance of training courses for teachers and school staff to enhance their ability to detect and deal with bullying cases. This recommendation has a mean of 2.74 and an SD of 1.12 (Table 7). Another medium-significance intervention ranked sixth for applying penalties against bullies. This intervention has a mean score of 2.16 and an SD of 1.10 (Table 7).

3.5. The Frequency of School Bullying Dimensions across Gender, School Type, and Students’ Grades

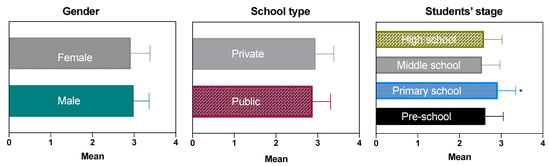

Figure 2 indicates that there are no statistically significant differences between gender or school types in the responses of mothers of children with ASD to dimensions of bullying. However, there are statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between school stages, with students at primary school experiencing more bullying.

Figure 2.

The frequency of school bullying experienced by children with ASD across several aspects. * p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Children with special needs, such as ASD, are considered more vulnerable to aggressive behaviors at school, such as bullying, due to their challenges in communication and with connections. School bullying has a pronounced negative impact on multiple aspects of children’s life, including academic achievement and mental health [10].

School bullying for children with ASD is still overlooked, although this topic has been extensively investigated in recent years globally. In this study, we focus on identifying the frequency and severity of school bullying against children with ASD, a critical category of special needs. We measure the level of school bullying experienced by children in three dimensions, physical, verbal, and social, from the perspective of their mothers.

It is important to indicate here that mothers’ perspectives on the severity and type of bullying their children encounter were chosen as the primary source of evaluation since they are the primary caregivers. Furthermore, mothers are typically more able to observe signs of distress and behavior changes in their children, since they spend more time with them. In the context of ASD, they are most likely more sensitive to their children’s social and emotional communication challenges.

Regarding the bullying aspects, verbal bullying (such as the use of offensive names and making fun of stereotypical behaviors) and physical bullying are considered the most frequent forms of bullying, where the differences in the means are relatively small. However, the standard deviations suggest less variability in these types of bullying than in physical bullying. These results are consistent with a study by Cappadocia et al. [16], which demonstrated that children with ASD experience more frequent verbal and social bullying, and a study revealed that five-year-old children with ASD had experienced various forms of bullying, notably being picked on, excluded, and called names [4]. In alignment with these results, a meta-analysis which included 17 studies of school-aged students with ASD revealed that the prevalence of physical, verbal, and relational school victimization was 33%, 50%, and 31%, respectively [17]. Moreover, a study conducted in Turkey found that children with ASD are more likely to experience verbal and emotional bullying, with a positive correlation observed between the severity of ASD and bullying incidents [19]. The prevalence of verbal bullying can be attributed to its strong correlation with the communication and emotional challenges associated with ASD. Therefore, effective anti-bullying interventions that target peers and focus on the role of educators and empathy-building are paramount, since a deficiency in empathic understanding among peers toward children with ASD intensifies this form of bullying [39].

The impact of school bullying on students’ academic achievement and belonging is significant, and originates from the distraction caused by psychological stress. Students with special needs are particularly vulnerable to adverse effects on academic performance due to bullying, resulting in a decline in overall achievement [39]. Given these findings, developing effective muti-sided strategies to address school bullying is crucial. This includes providing training and support to teachers, increasing awareness of the importance of cooperation between teachers and students’ peers, and creating a supportive school environment.

In this study, we proposed a set of interventions and initiatives to prevent and mitigate the negative impacts of bullying and measured the degree of acceptance among mothers. The results indicated that among the proposed anti-bullying interventions, the implementation of training programs specifically designed for students and parents with ASD on handling bullying and the appointment of school employees dedicated to monitoring and supporting affected students received strong agreement among mothers regarding their effectiveness. Prioritizing such interventions by mothers is expected and justified, because of the strong correlation between these interventions and verbal and social bullying, which often correlate with the communication and social challenges their children face. What makes it painful for children and mothers is that verbal bullying, such as name-calling, directly targets the communication difficulties commonly experienced by children with ASD. Similarly, social bullying, which involves exclusion or manipulation of social relationships, can nourishes feelings of exclusion that are already prevalent in children with ASD. Therefore, mothers may prioritize these measures as they closely align with the unique challenges their children encounter, prompting high awareness and concern towards these specific forms of bullying. Furthermore, these measures confirm the importance of cooperation between teachers, students, and parents, in addition to the management teams, to prevent such abusive behavior towards children with special needs such as ASD. Studies in the literature highlight the importance of therapeutic and preventive solutions and interventions for bullying, such as supportive and collaborative teacher interventions and programs designed to prevent bullying among students that generally focus on increasing children’s emotional and social competence and assertiveness skills [40]. Downes and Cefai found that parent training significantly reduces school bullying and violence, emphasizing the need for collaborative efforts among families, communities, and educators to create a safe and supportive school environment [41]. The overall results highlighted the importance of a multifaceted approach involving policy development, training for students, teachers, and parents, and the appointment of dedicated staff to oversee bullying prevention and intervention. Additionally, enhancing social and emotional competencies is crucial to mitigate the negative impact of bullying on children and youth with ASD [42].

Interestingly, our results revealed no significant difference between males and females in experiencing bullying behaviors, which aligns with the results of a study by Al-Maliki and Sahab, which concluded that there are no statistically significant differences in gender in bullying [15]. Nevertheless, Jaradat et al. found that male students in Jordan experience more bullying in three dimensions (victim, bully, and victim-bully) than females [43]. This outcome can be attributed to traditional norms that prioritize assertiveness, physical strength, and social involvement, which may conflict with the social and emotional interaction and communication associated with ASD [44]. Consequently, males with ASD become targets for bullying.

On the other hand, our results indicated that students at primary school may experience more bullying behavior than students at higher levels of education. This finding can be attributed to the limited social skills younger children have in general, which are critical for peer interactions, rendering them more vulnerable to bullying. In agreement with these results, a study by Chen and Schwartz revealed that elementary students with high-functioning autism face a higher risk of victimization than their typically developing peers [45]. Another research study found that primary and middle school students with autism were at the highest risk of bullying incidences in the United States [46].

5. Limitations of the Study

While this study provides valuable insights into the prevalence and types of bullying experienced by children with ASD in Jordan, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. First, the study relies on mothers’ perspectives, which, while providing rich and detailed insights, may only capture part of the full scope of the bullying experiences from other viewpoints. Second, the sample size is relatively small, and may not fully represent all children with ASD in Jordan. Third, the study focuses on a specific cultural context, and the findings may not be generalizable to other regions or cultures. Additionally, while mothers’ perspectives toward proposed anti-bullying measures provide valuable insights, specific suggestions on interventions might be most effective and add more value.

6. Future Lines of Research

Future studies should explore bullying towards children with ASD from the perspectives of schools, teachers, and peers in Jordan. This multi-faceted approach will offer a more comprehensive understanding of the issue. Additionally, future research should assess the presence and effectiveness of current anti-bullying measures and their contribution to preventing bullying. Including qualitative suggestions from mothers will further enrich the findings by providing insights into their experiences and the challenges to implementation. Investigating these areas is strongly recommended to enhance support and protection for children with ASD in schools.

7. Conclusions

Understanding the prevalence and severity of different bullying aspects towards children with ASD is crucial, given the negative consequences they face. In this study, we examined the frequency and severity of three dimensions of school bullying against children with ASD from the perspectives of 70 mothers of children with ASD in the capital, Amman, Jordan. The results revealed that children with ASD frequently experience verbal and physical bullying followed by social bullying. Additionally, the findings indicated that mothers of children with ASD agree with the set of interventions proposed against bullying. Among these practices, they focused on implementing training programs for students and parents to address and mitigate such abusive behaviors, thereby enhancing the communication skills of these individuals. Furthermore, mothers support the interventions related to appointing specific personnel responsible for monitoring and preventing bullying and supporting bullied students within the school environment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/soc14090157/s1, Table S1: The survey tool used to measure the frequency of bullying experienced by children with ASD and the agreement degree of their mothers to a set of interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.K. and M.A.A.J.; Methodology, E.M.K.; Validation, E.M.K. and M.A.A.J.; Formal analysis, E.M.K.; Investigation, E.M.K. and M.A.A.J.; Resources, E.M.K.; Data curation, E.M.K.; Writing—original draft, E.M.K.; Writing—review & editing, M.A.A.J.; Supervision, E.M.K.; Project administration, E.M.K. and M.A.A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Zarqa University College, Al-Balqa Applied University (approval number: 6523/1/11/2023/6923).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Smith, P.K. Bullying: Definition, Types, Causes, Consequences and Intervention. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2016, 10, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladden, R.M.; Vivolo-Kantor, A.M.; Hamburger, M.E.; Lumpkin, C.D. Bullying Surveillance among Youths: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Education: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus, D. School bullying: Development and some important challenges. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 751–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saigh, B.H.; Bagadood, N.H. Bullying experiences and mothers’ responses to bullying of children with autism spectrum disorder. Discov. Psychol. 2022, 2, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Huang, S.; Evans, R.; Zhang, W. Cyberbullying Among Adolescents and Children: A Comprehensive Review of the Global Situation, Risk Factors, and Preventive Measures. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 634909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, F.; Senin, M.; Nordin, M.N.B.; Hasyim, M. A qualitative study: Impact of bullying on children with special needs. Linguist. Antverp. 2021, 2, 1639–1643. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, D.J.; Todres, J.; Bradshaw, C.P.; Amar, A.F.; Graham, S.; Hatzenbuehler, M.; Masiello, M.; Moreno, M.; Sullivan, R.; Vaillancourt, T.; et al. Bullying Prevention: A Summary of the Report of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Prevention Science 2016, 17, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S.E.; Norman, R.E.; Suetani, S.; Thomas, H.J.; Sly, P.D.; Scott, J.G. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Psychiatry 2017, 7, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, N.A.; Katsiyannis, A.; Rose, C.; Adams, S.E. Disproportionate Bullying Victimization and Perpetration by Disability Status, Race, and Gender: A National Analysis. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2021, 5, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.; Gong, J.; Lyons, G.L.; Hirota, T.; Takahashi, M.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, J.; Leventhal, B.L. Prevalence of and Factors Associated with School Bullying in Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Cross-Cultural Meta-Analysis. Yonsei Med. J. 2020, 61, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M. Systematic Review: Bullying Involvement of Children with and without Chronic Physical Illness and/or Physical/Sensory Disability—A Meta-Analytic Comparison with Healthy/Nondisabled Peers. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2017, 42, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5™, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013; pp. 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zeedyk, S.M.; Rodriguez, G.; Tipton, L.A.; Baker, B.L.; Blacher, J. Bullying of youth with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or typical development: Victim and parent perspectives. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2014, 8, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junttila, M.; Kielinen, M.; Jussila, K.; Joskitt, L.; Mäntymaa, M.; Ebeling, H.; Mattila, M.L. The traits of Autism Spectrum Disorder and bullying victimization in an epidemiological population. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Maliki, W.A.; Sahab; Abdel-Hakim, L. The most common forms of school bullying against students with autism spectrum disorder and their causes from the point of view of their teachers in Jeddah. J. Educ. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 7, 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cappadocia, M.C.; Weiss, J.A.; Pepler, D. Bullying experiences among children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maïano, C.; Normand, C.L.; Salvas, M.C.; Moullec, G.; Aimé, A. Prevalence of School Bullying among Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Autism Res. 2016, 9, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochi, M.; Kawabe, K.; Ochi, S.; Miyama, T.; Horiuchi, F.; Ueno, S.-i. School refusal and bullying in children with autism spectrum disorder. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eroglu, M.; Kilic, B.G. Peer bullying among children with autism spectrum disorder in formal education settings: Data from Turkey. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2020, 75, 101572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Inclusion and Gender Equality—Brief on Inclusion in Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger, H.K. Impact of workplace mistreatment on patient safety risk and nurse-assessed patient outcomes. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2014, 44, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salimi, N.; Karimi-Shahanjarini, A.; Rezapur-Shahkolai, F.; Hamzeh, B.; Roshanaei, G.; Babamiri, M. The Effect of an Anti-Bullying Intervention on Male Students’ Bullying-victimization Behaviors and Social Competence: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Deprived Urban Areas. J. Res. Health Sci. 2019, 19, e00461. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell, D.; Limber, S.P. Law and policy on the concept of bullying at school. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. School Violence and Bullying: Global Status Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Axford, N.; Farrington, D.P.; Clarkson, S.; Bjornstad, G.J.; Wrigley, Z.; Hutchings, J. Involving parents in school-based programmes to prevent and reduce bullying: What effect does it have? J. Child. Serv. 2015, 10, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, N.; Hebron, J. Bullying of children and adolescents with autism spectrum conditions: A ‘state of the field’ review. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, C. “They Just Want Us to Exist as a Trash Can”: Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Their Perspectives to School-Based Bullying Victimization. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2023, 27, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatawi, A. Types of Bullying and its Causes for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Full-Inclusion Programs: Teachers ‘and Parents’ Opinions. Inf. Sci. Lett. 2023, 12, 2505–2519. [Google Scholar]

- Alqhazo, M.T.; Hatamleh, L.S.; Bashtawi, M. Phonological and lexical abilities of Jordanian children with autism. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2020, 9, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyassat, M.; Al-Makahleh, A.; Rahahleh, Z.; Al-Zyoud, N. The Diagnostic Process for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Preliminary Study of Jordanian Parents’ Perspectives. Children 2023, 10, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Raqqad, H.K.; Al-Bourini, E.S.; Al Talahin, F.M.; Aranki, R.M.E. The Impact of School Bullying on Students’ Academic Achievement from Teachers Point of View. Int. Educ. Stud. 2017, 10, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Ending School Bullying: Focus on the Arab States; UNESCO’s Contribution to the Policy Dialogue on Bullying and Learning Organized by the Regional Center for Educational Planning United Arab Emirates, April 2019; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, A.M.; Hammad, S.; Haourani, E.M.; Nassar, O.S. Factors Affecting Jordanian School Adolescents’ Experience of Being Bullied. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 38, e66–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Charles, K. Enhancing the sample diversity of snowball samples: Recommendations from a research project on anti-dam movements in Southeast Asia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisala, M.; Ndhlovu, D.; Mandyata, J.M. Child Protection Measures on Bullying in Special Education Schools. Eur. J. Spec. Educ. Res. 2023, 9, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romera, E.M.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Rodríguez-Barbero, S.; Falla, D. How Do You Think the Victims of Bullying Feel? A Study of Moral Emotions in Primary School. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, M.E.; Smith, G.T. Construct validity: Advances in theory and methodology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 5, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M. The Impact of Bullying in an Inclusive Classroom Among Students of ASD and Peers in Social Development and Academic Performance in UAE. In Proceedings of the BUiD Doctoral Research Conference 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wachs, S.; Bilz, L.; Niproschke, S.; Schubarth, W. Bullying Intervention in Schools: A Multilevel Analysis of Teachers’ Success in Handling Bullying from the Students’ Perspective. J. Early Adolesc. 2018, 39, 642–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, P.; Cefai, C. How to Prevent and Tackle Bullying and School Violence—Evidence and Practices for Strategies for Inclusive and Safe Schools; NESET II; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tipton-Fisler, L.A.; Rodriguez, G.; Zeedyk, S.M.; Blacher, J. Stability of bullying and internalizing problems among adolescents with ASD, ID, or typical development. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 80, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, A.-K.M. Gender Differences in Bullying and Victimization among Early Adolescents in Jordan. PEOPLE Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 3, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- San Martin, A.; Sinaceur, M.; Madi, A.; Tompson, S.; Maddux, W.W.; Kitayama, S. Self-assertive interdependence in Arab culture. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.-Y.; Schwartz, I.S. Bullying and Victimization Experiences of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Elementary Schools. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2012, 27, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J.J.; Lund, E.M.; Zhou, Q.; Kwok, O.M.; Benz, M.R. National prevalence rates of bully victimization among students with disabilities in the United States. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2012, 27, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).