A Gendered Lens on Mediation and Market Governance: Experiences of Women Market Vendors in Papua New Guinea

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Few cities in the Pacific have supportive policy frameworks for informal economic activities despite their prevalence and persistence. Where policies exist, they are often punitive and top-down, restricting people’s agency and innovation; and even when policies are supportive of the informal sector, such as in Papua New Guinea (PNG), markets can remain precarious and without services.”

2. Background

2.1. Women and Informal Markets

“The informal economy has been considered as a possible fallback position for women who are excluded from paid employment. It is often the only source of income for women in the developing world, especially in those areas where cultural norms bar them from work outside the home or where, because of conflict with household responsibilities, they cannot undertake regular employee working hours.”[11] (p. 10)

2.2. Women and Informal Economic Activities in Papua New Guinea and the Pacific

“…most respondents in the community markets we studied felt secure because of kin and community relationships within the market, and between the markets and the adjacent community. Low-level security concerns still exist with respect to drinking, bullying and theft, but the stronger the links between the local community and the market, the better these issues are managed”[4] (p. 2)

“People are prepared to invest a major, and at times astonishing, quantity of their time and capital in these everyday forms, functions, and regulatory processes in order to stretim hevi [in Tok Pisin (PNG’s most widely used language): solve problems] and create gutpela sindaun [good, liveable places].”[6] (p. 4)

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Women Vendors’ Motivations and Challenges of Safe and Unsafe Market Spaces

“I have two boys, I want their future to be better, and not like mine, who struggle to sell betelnut to meet my needs every day. I want them to stay in school and work hard at it so they can find good jobs and think about their siblings and have better future. That’s why I am at the market.”(female participant) [30]

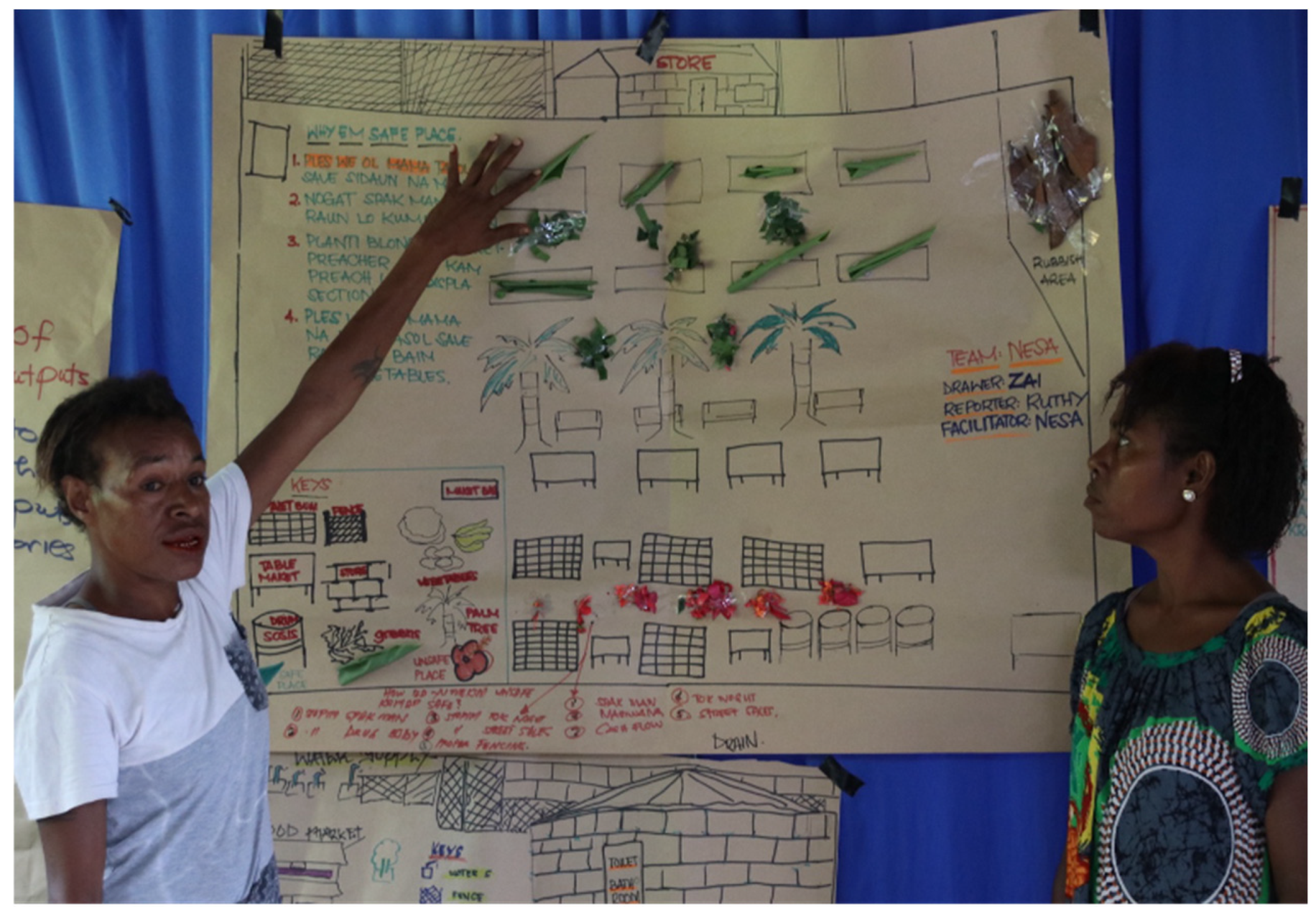

“…this is the map of Awagasi market, which we drew […] The red colour on the map represents unsafe spaces. We want consumption of alcohol in the market to stop.”(female participant) [30]

“When the drunkard people come to the market, they go straight to betelnut section and incite a quarrel with table market vendors, and grab their betelnut and smoke, and that is when fights occur.”(male participant) [30]

“Waste disposal places are unsafe, and we indicated it with red and when we walk past the rubbish place, we block our noses to prevent breathing in the bad odour from decomposition of the market waste.”(male participant) [30]

4.2. Innovations in Market Governance and Leadership

“…women’s leadership inside the market is important. Mothers know their roles because they play bigger roles to take care of their own homes and they work hard at the market.”(male participant) [32]

“Sometimes their husbands get angry with them, but mothers work hard to earn money to put food on the table. So, such conflict exists but mothers know their rights to protect themselves. We talk about gender equality, violence against women; we need women leadership to address these issues.”(male participant) [32]

“The male leaders respect us women leaders; we women leaders also respect the male leaders, so we hold the same positions inside our Awagasi community.”(female participant) [33]

“Settlement community here must be responsible for Awagasi market; we must feel that it is a place where we earn for our living, and our mothers use this place to earn in income, so we must feel responsible of this market. When problems occur, we must solve them and if they escalate, we must seek help from the police to solve the problems.”(female participant) [34]

“Our work as women leader involves looking after the needs of women, in particular younger women; we work closely with the male leaders to ensure that we have a peaceful community.”(female participant) [33]

4.3. Women Vendors’ Strategies in Conflict Management

“If there is a conflict, we bring both parties together to sit with us and for us to assess the situation. We often find that we need to resolve issues the PNG way, to say sorry, it can mean a lot.”(female participant) [33]

“…sometimes when problems happen at the market, when they say let us solve the problem, we, the table mothers, market mothers and betelnut sellers, think about our market and contribute money ourselves.”(female participant) [33]

“Community leaders help quickly and stop people from hitting and quarrelling with one another. One thing is that the landowner of the market quickly stands against this, so the male youths get afraid of him. So, when problems start and he gets up and stands in the middle, fighting with another goes down quickly.”(female participant) [33]

“When we see that there is an issue in a family, we women leaders come together and discuss how we can help to resolve the issue. It is not enough just for me as female leader to do something, I must get the other leaders involved, so that we can collectively address the issue.”(female participant) [33]

“We would like the government to collaborate with us to address mothers’ and young women’s safety. I think the government, NGO and all of us should partner because this safety is our responsibility.”(female participant) [34]

5. Discussion

5.1. Activating Social Relationships and Social Bonds

“In the absence of effective or responsive state institutions, local activists and social innovators, many of them women, are driving violence prevention and resolution efforts. They leverage their social networks and insider knowledge to foster sustainable changes and can reach populations that conventionally designed programs often miss.”[36] (p. 13)

“…‘co-produce’ authority and regulation by enrolling the support of residents and by impacting and working together with fellow recognized ethnic and other leaders. In doing so, albeit with highly uneven effectiveness in relation to gender and violence, they can help produce, combine, and protect some of the rich but precarious capital that is produced and accumulates in urban settlements.”(p. 5)

5.2. Women Taking Charge of Market Spaces

5.3. Men’s Roles in Supporting Women’s Safety

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barbara, J.; Baker, K. Addressing collective action problems in Melanesia: The Northern Islands Market Vendors’ Association in Vanuatu. Dev. Pract. 2020, 30, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.; Walsh, K.; Frosch, M. Engendering informality statistics: Gaps and opportunities: Working paper to support revision of the standards for statistics on informality. In ILO Working Paper 2022; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Underhill-Sem, Y.; Cox, E.; Lacey, A.; Szamier, M. Changing market culture in the Pacific: Assembling a conceptual framework from diverse knowledge and experiences. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2014, 55, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, M.; Ride, A. Markets Matter: ANU-UN Women Project on Honiara’s Informal Markets in Solomon Islands. In Brief 2018/9; ANU Department of Pacific Affairs: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hedditch, S.N. Economic Opportunities for Women in the Pacific; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, D.; Porter, D. Safety and Security at the Edges of the State: Local Regulation in Papua New Guinea’s Urban Settlements; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F. The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Polman, N.; Slee, B.; Kluvánková, T.; Dijkshoorn-Dekker, M.W.C.; Nijnik, M.; Gežík, V.; Soma, K. Classification of Social Innovations for Marginalized Rural Areas. In SIMRA Project Report; SIMRA: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, R.; Fink, M.; Lang, R.; Maresch, D. Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Rural Europe; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkki, S.; Torre, C.D.; Fransala, J.; Živojinović, I.; Ludvig, A.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Melnykovych, M.; Sfeir, P.R.; Arbia, L.; Bengoumi, M.; et al. Reconstructive social innovation cycles in women-led initiatives in rural areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, S.; Schmidt, D. Global Employment Trends for Women, 2004; International Labour Office: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, J. Informal Women Workers in the Global South: Policies and Practices for the Formalisation of Women’s Employment in Developing Economies; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Panneer, S.; Acharya, S.; Sivakami, N. Health, Safety and Well-Being of Workers in the Informal Sector in India Lessons for Emerging Economies, 1st ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney, M.N. Sharing what can be sold: Women Haus Maket vendors in Port Moresby’s settlements. Oceania 2019, 89, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chant, S. Cities through a “gender lens”: A golden “urban age” for women in the global South? Environ. Urban. 2013, 25, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopel, E. The Informal Economy in Papua New Guinea: Scoping Review of Literature and Areas for Further Research; Issues Paper; The National Research Institute: Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 2017; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Olutayo, M.S.A. Women and Conflict Management in Selected Market Places in Southwestern Nigeria. Afr. Dev. 2014, 39, 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Hukula, F. Morality and a Mosbi Market. Oceania 2019, 89, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopel, E.; Au, R.; Iwong, L.; Tukne, C. Innovation in the Informal Economy: Lessons from Case Studies in Selected Areas of Three Provinces in Papua New Guinea; Discussion Paper; The National Research Institute: Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 2021; Volume 186. [Google Scholar]

- PNG Department for Community Development. National Informal Economy Policy 2011–2015; Department for Community Development and the Institute of National Affairs: Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. Making Port Moresby Safer for Women and Girls: A Scoping Study; United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women): Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Georgeou, N.; Hawksley, C.; Monks, J.; Ride, A.; Ki’i, M.; Barrett, L. Food Security in Solomon Islands: A Survey of Honiara Central Market: Preliminary Report; HADRI, Western Sydney University: Penrith, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liki, A. Travelling Daughters: Experiences of Melanesian-Samoan Women. Development 2009, 52, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnegie, M.; McKinnon, K.; Gibson, K. Creating community-based indicators of gender equity: A methodology. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2019, 60, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, S. The Interview as Method: Doing Feminist Research; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mertova, P. Using Narrative Inquiry as a Research Method: An Introduction to Critical Event Narrative Analysis in Research, Training and Professional Practice, 2nd ed.; Webster, L., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Finley, S. Arts-based research. In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gutsche, R.E. News place-making: Applying ‘mental mapping’ to explore the journalistic interpretive community. Vis. Commun. 2014, 13, 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.H.M.; Chiang, V.C.L.; Leung, D. Hermeneutic phenomenological analysis: The ‘possibility’ beyond ‘actuality’ in thematic analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1757–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creative Mapping Workshop Lae with market vendors and stakeholders. Facilitated by Wilma Langa, March 2020.

- World Bank Group. Papua New Guinea: Sanitation, Water Supply and Hygiene in Urban Informal Settlements. In Papua New Guinea; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Interview Hiob Awagasi; Lae. Interviewer: Wilma Langa, March 2020: Lae.

- Focus Group Lae with Women Market Vendors. Facilitated by Wilma Langa, March 2020.

- Focus Group Lae with Men Market Vendors. Facilitated by Wilma Langa, March 2020.

- Bukari, S.; KBukari, N.; Ametefe, R. Market women’s informal peacebuilding efforts in Ekumfi-Narkwa, Ghana. Can. J. Afr. Stud./Rev. Can. Études Afr. 2022, 56, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abay, N.A.; Kuehnast, K.; Peake, G.; Demian, M. Addressing Gendered Violence in Papua New Guinea: Opportunities and Options; Special Report; United States Institute of Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, D.; Porter, D.; Hukula, F. ‘Come and See the System in Place’ Mediation Capabilities in Papua New Guinea’s Urban Settlements; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, M.; Sharp, T.L.M. Marketplaces and Morality in Papua New Guinea: Place, Personhood and Exchange. Oceania 2019, 89, 126–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, M. Involving Men in Efforts to End Violence Against Women. Men Masculinities 2011, 14, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, P. Men’s matters: Changing masculine identities in Papua New Guinea. In Gender Violence and Human Rights: Seeking Justice in Fiji, Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu; Birsack, A., Jolly, M., Macintyre, M., Eds.; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2016; pp. 127–158. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Langa, W.; Kauli, J.; Thomas, V. A Gendered Lens on Mediation and Market Governance: Experiences of Women Market Vendors in Papua New Guinea. Societies 2024, 14, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14080155

Langa W, Kauli J, Thomas V. A Gendered Lens on Mediation and Market Governance: Experiences of Women Market Vendors in Papua New Guinea. Societies. 2024; 14(8):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14080155

Chicago/Turabian StyleLanga, Wilma, Jackie Kauli, and Verena Thomas. 2024. "A Gendered Lens on Mediation and Market Governance: Experiences of Women Market Vendors in Papua New Guinea" Societies 14, no. 8: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14080155

APA StyleLanga, W., Kauli, J., & Thomas, V. (2024). A Gendered Lens on Mediation and Market Governance: Experiences of Women Market Vendors in Papua New Guinea. Societies, 14(8), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14080155