1. Introduction

The role of women entrepreneurs in the economy is significant and multifaceted [

1]. Women-led businesses have the potential to create jobs, stimulate economic growth, and promote gender equality and diversity [

2], especially in developing nations [

3,

4,

5]. By starting and growing successful businesses, women entrepreneurs can act as drivers of economic development and help to create more inclusive and prosperous communities [

4].

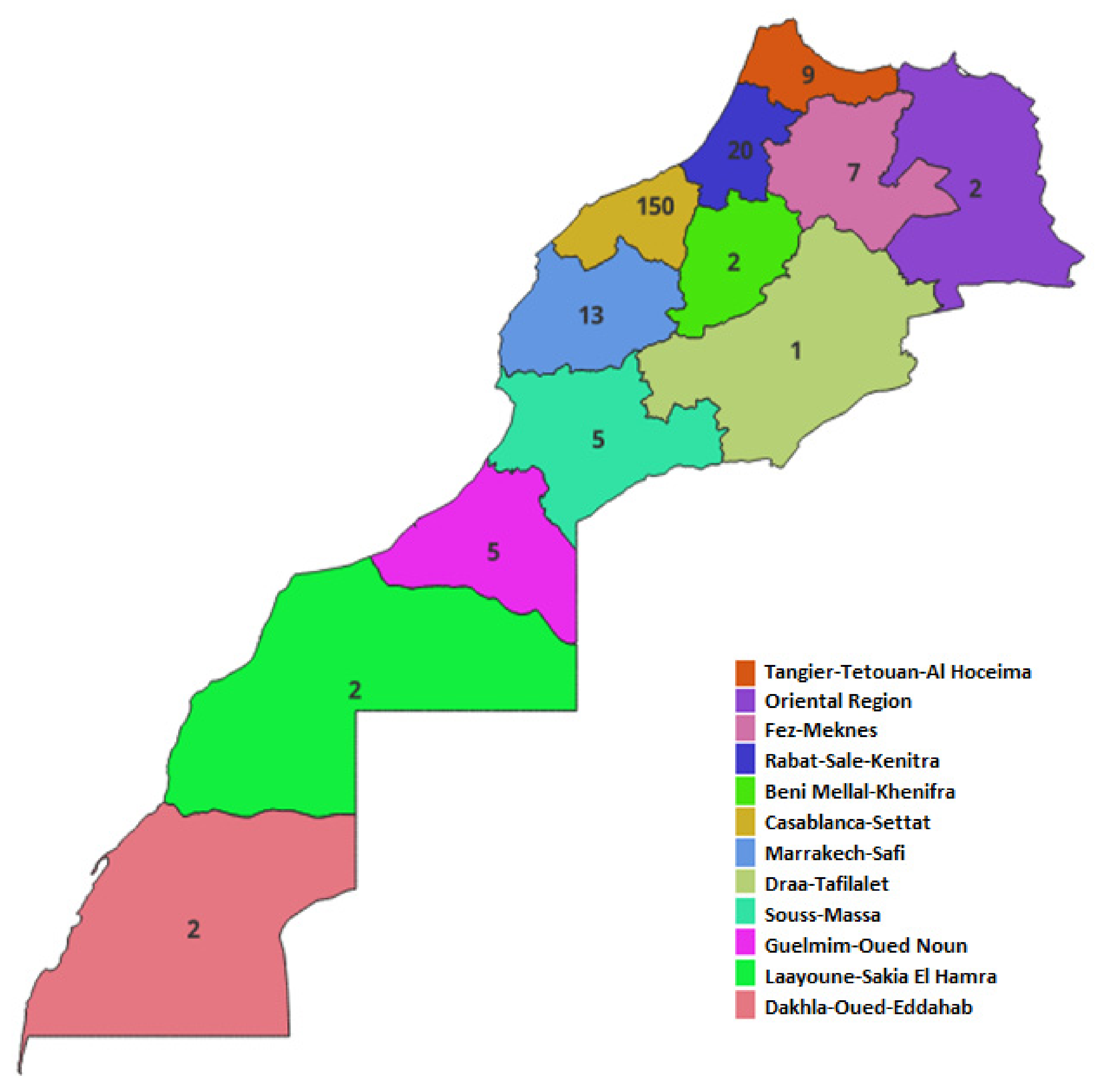

Given the significance of women entrepreneurs in driving economic development, several initiatives have been initiated in Morocco to promote and support female entrepreneurship. The Moroccan government has implemented policies and programs to promote gender equality and support women entrepreneurs. Additionally, there are various NGOs and international organizations working to support women’s empowerment in Morocco through education, training, and access to resources. These include support programs like the START-ELLES program, a collaborative effort between the National Initiative for Human Development (INDH) and Enactus, specifically designed to bolster entrepreneurship, with a focus on rural women. Additionally, there are financing programs such as the Forsa program, which has surpassed its initial goal of funding 10,000 projects by 2023. This success has resulted in the financing of over 5000 projects led by women, constituting 45% of the total beneficiaries.

Despite extensive initiatives to encourage female entrepreneurship in Morocco, the proportion of women entrepreneurs remains modest. The Moroccan observatory for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (OMTPME) report from October 14, 2022, revealed that women lead only 16.2% of active businesses in Morocco [

6]. Given this context, the Association of Moroccan Women Entrepreneurs (AFEM) has continually campaigned since its creation in September 2000 for the re-establishment of laws favorable to women entrepreneurs [

7].

Analyzing the success of female entrepreneurs entails recognizing the impediments that may impede women in their entrepreneurial pursuits [

8]. Prior studies have specifically delved into the diverse challenges confronted by women entrepreneurs, including insufficient access to education and training [

9], relative lack of experience [

10], lack of family and institutional support [

11], and difficulties in securing financial resources [

12].

Entrepreneurship can be especially challenging for women in developing nations due to limited opportunities, resource constraints, and distinctive obstacles such as juggling work and family responsibilities, navigating patriarchal societies, and confronting gender discrimination [

13,

14]. Women entrepreneurs in Arab-Muslim and patriarchal societies may face various challenges, including cultural and societal attitudes that limit opportunities for women in business, lack of access to education and resources, and lack of government support [

15].

As in other developing countries, Moroccan women entrepreneurs face various difficulties in their business endeavors, arising from societal norms that prescribe traditional roles for women [

16,

17]. Although women’s employment is gaining increasing value in the Moroccan society, social representations remain influenced by male supremacy and a strong gender distinction [

18]. Despite the challenges they face, Moroccan women entrepreneurs exhibit remarkable resilience and creativity in overcoming obstacles and establishing successful businesses across various sectors [

19].

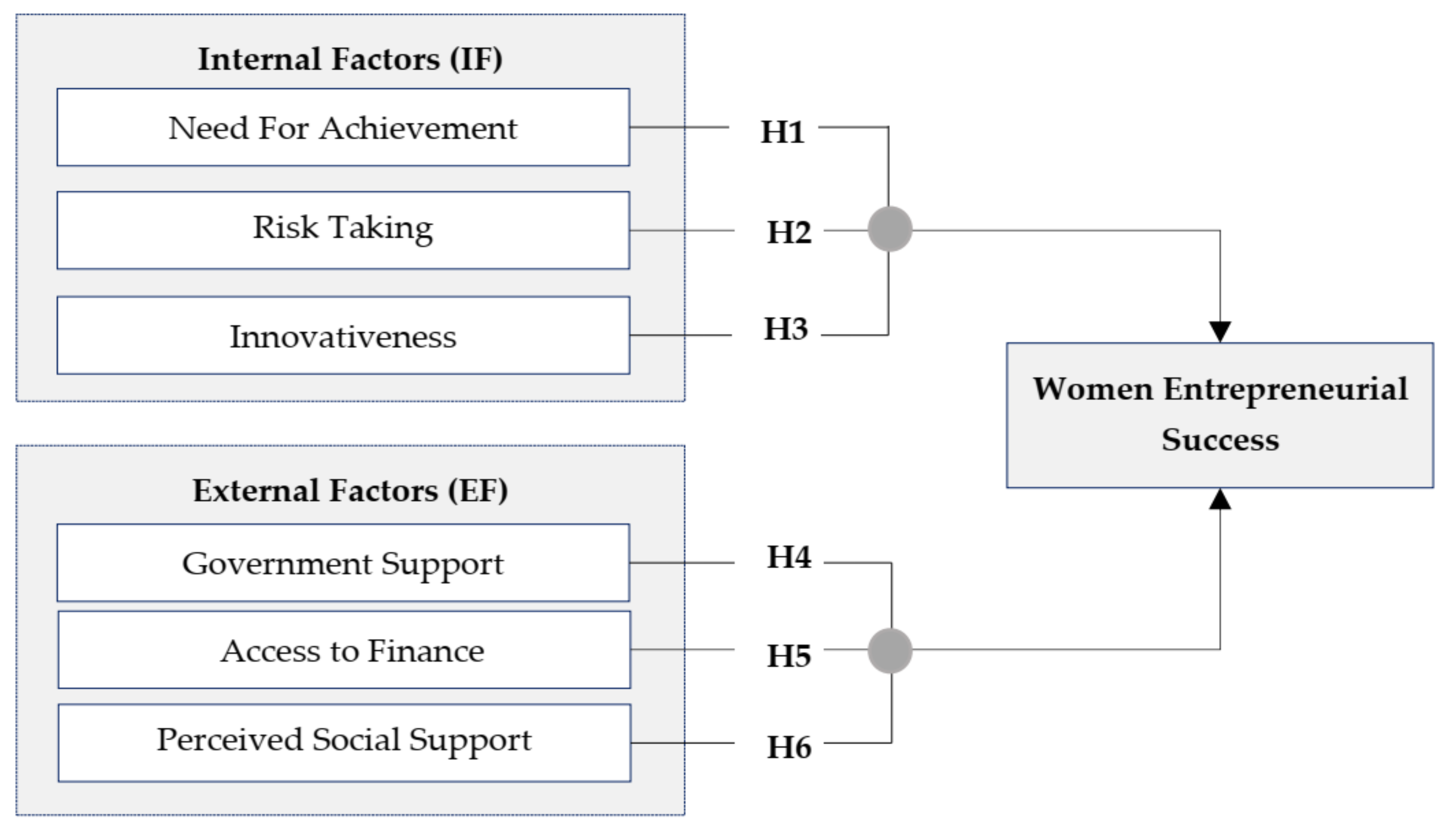

Several earlier studies have been conducted on the determinants of the entrepreneurial success of women in different contexts [

2]. However, there is still a lack of scholarship focusing on the success of female entrepreneurs in a Muslim and patriarchal society. Hence, the current study seeks to address this gap by examining the role of internal and external factors in the entrepreneurial success of Moroccan women. The analysis of entrepreneurial success determinants by focusing on internal and external factors jointly delivers a holistic understanding of challenges and opportunities that women entrepreneurs face. Therefore, the understanding of how internal and external factors interact can lead to more efficient strategies for empowering women entrepreneurs.

For this purpose, the current study seeks to identify factors influencing the entrepreneurial success of Moroccan women by addressing the following questions:

RQ1. Which personal factors lead to Moroccan women achieving entrepreneurial success?

RQ2. How do external factors (i.e., government support, access to finance, and social support) shape Moroccan women’s success in entrepreneurship?

To address these specific research questions, we mobilized the social feminist theory to explore the determinants of women’s entrepreneurial success, focusing on the role of internal and external factors. Furthermore, an online survey approach was adopted, enabling cost-effective data collection from a diverse and geographically dispersed sample of Moroccan women entrepreneurs.

The rest of the paper consists of six sections.

Section 2 contains the literature review.

Section 3 provides the justification for the development of the study model.

Section 4 outlines the materials and methods.

Section 5 reports the results, followed by a discussion of the findings in

Section 6. The final section outlines the key implications of the study and suggests directions for future research.

6. Discussions

Based on social feminist theory, which asserts that women act differently from men, it is essential to consider women’s specific characteristics when identifying the determinants of Moroccan women entrepreneurs’ success.

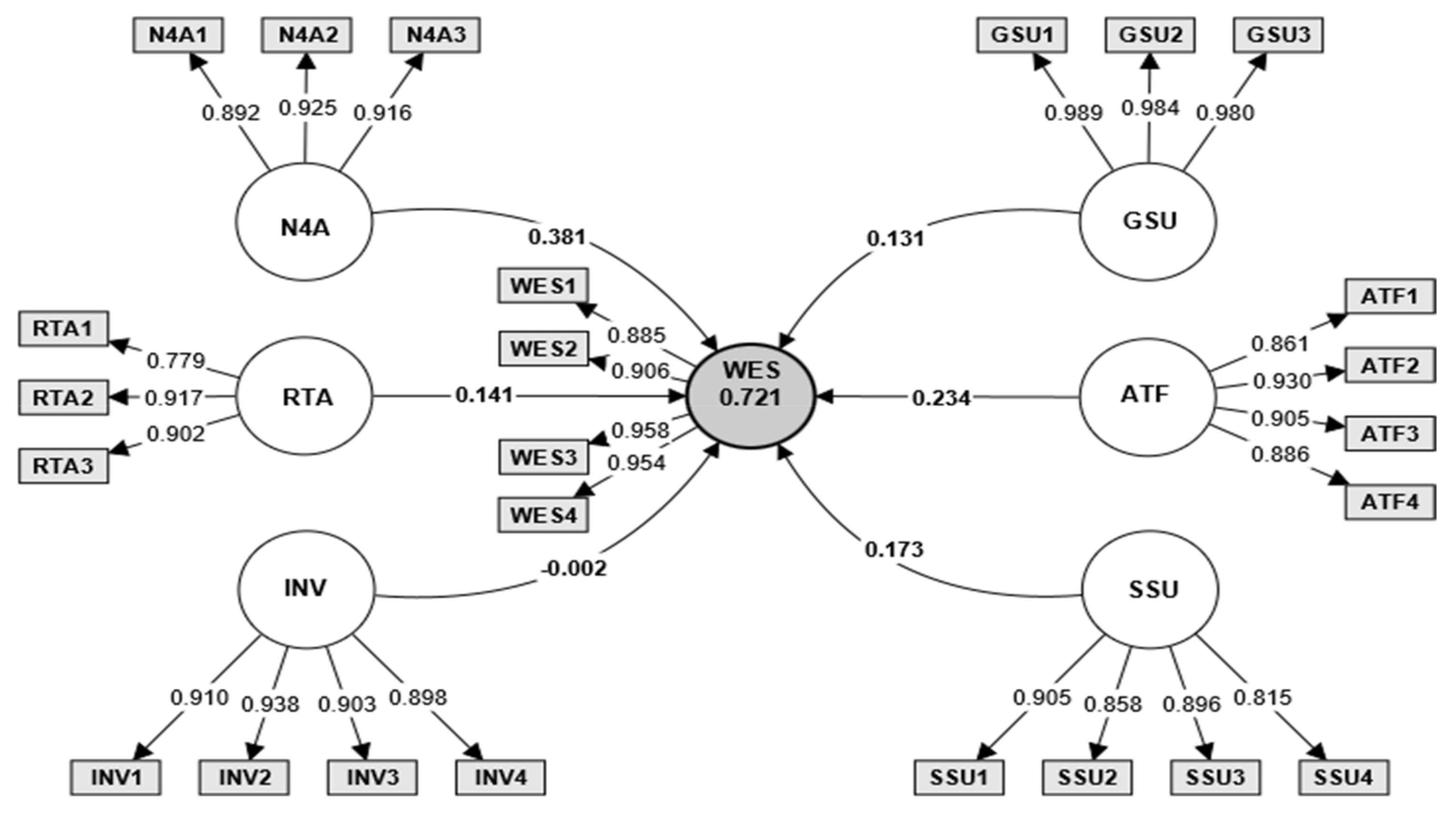

The study findings indicate that Moroccan women’s entrepreneurial success is directly and significantly influenced by internal factors such as the need for achievement and risk-taking, as well as by external factors including government support, access to finance, and social support from family and friends.

Need for achievement was found to be the biggest determinant of Moroccan women’s entrepreneurial success. In other words, the Moroccan women who exhibited a strong drive and aspiration for accomplishing their goals and succeeding in their entrepreneurial endeavors tended to experience greater success in their business ventures. This underscores the importance of intrinsic motivation and a sense of achievement in fostering entrepreneurial success among women in the Moroccan context. This result is supported by earlier empirical studies [

2,

38], which established that female owners of SMEs exhibiting elevated levels of the need for achievement are more prone to achieving success in their ventures.

The current study result indicated that there is a direct, significant, and positive influence of risk-taking on the entrepreneurial success of Moroccan women. This finding aligns with earlier studies [

2,

51], which also affirmed that the increased willingness to take risks plays a crucial role in driving entrepreneurial efforts. Individuals who believe in their ability to foresee success and perceive a minimal chance of failure are more inclined to see potential opportunities in their ideas. Consequently, embracing risk becomes a pivotal factor in determining the success of female entrepreneurs, as taking risks is frequently essential for initiating and expanding a business.

The findings of the present study also indicate a lack of association between innovativeness and entrepreneurial success. This result is in line with the study of Chatterjee et al. [

32] conducted in India among micro-entrepreneurs, who confirmed that innovativeness does not affect the success of women entrepreneurs. These results may be explained through the fact that most of the women entrepreneurs who participated in the current study were mostly involved in traditional and/or well-established businesses, where there is little room for innovation.

This study’s outcomes affirm that government support exerts a direct and positive influence on the success of Moroccan women entrepreneurs. These findings align with prior studies [

33,

34,

55,

56], suggesting that women entrepreneurs who benefit from government assistance programs, encompassing the formulation of policies and legal frameworks, technological initiatives, and incentive systems, are more likely to succeed in their ventures.

The findings also verified that Moroccan women’s entrepreneurial success is positively influenced by access to financial resources. This implies that women entrepreneurs attain superior outcomes in their businesses when they have access to financial resources. In this regard, the present study aligns with prior research conducted by Khalid et al. [

59], Bongomin et al. [

30], Bettoni et al. [

60], Jha and Alam [

62], and Chipfunde et al. [

58], who noted that women entrepreneurs achieve superior business performance when they have access to financial resources, such as loans, credit, and other funding options.

Finally, the findings revealed that social support from family and friends positively influences the entrepreneurial success of Moroccan women. This implies that women-owned businesses thrive and achieve greater success when surrounded by a strong network of support from their families and friends, encompassing moral, financial, and operational support. The findings of the present study align with the research results reported by prior studies [

33,

58,

69]. In the Moroccan context, Constantinidis et al. [

18] argued that family members play a significant role in assisting women to achieve greater entrepreneurial success by providing financial, professional, and moral support.

7. Conclusions

The purpose of the present study is to investigate factors that foster Moroccan women’s entrepreneurial success. For this purpose, a model was developed and validated using the PLS-SEM approach. The findings revealed that both internal factors, such as need for achievement and risk-taking, as well as external factors, including government support, access to finance, and social support from family and friends, were the main factors favoring women’s entrepreneurial success in a patriarchal society and developing country.

7.1. Theoretical Implications

While there are a considerable number of studies related to identifying factors for women’s entrepreneurial success, this subject remains under-explored in patriarchal societies [

76,

77].

From a theoretical perspective, the current study enhances our nuanced comprehension of the factors influencing women’s entrepreneurial success, providing valuable insights for researchers. Hence, the current study adds to the existing literature related to success of women in entrepreneurship, by identifying both internal and external factors that explain the entrepreneurial success of women in a patriarchal society and developing country.

Moreover, the study’s findings reinforce social feminism theory by illustrating how both individual traits and external supports are critical to women entrepreneurs’ success. This underscores the importance of a supportive social context, including government and social backing, as well as access to financial resources.

7.2. Managerial Implications

Besides the theoretical implications, the current study also offers managerial implications for women-owned businesses, as well as guidance for Moroccan policy-makers and financial institutions on what needs to be done to help women entrepreneurs succeed in their business ventures. In particular, the Moroccan government are urged to promote initiatives designed to deconstruct gender stereotypes, as well as to put more effort and resources into programs designed to promote women’s entrepreneurship, through the implementation of programs and policies designed to provide financing and facilities to enable women to have easy access to flexible, low-cost training programs and workshops.

For their part, the families and friends of women entrepreneurs can play an essential role in the success of women entrepreneurs by providing them with the emotional help and support they need and assisting in decision-making. In terms of access to finance, funding organizations, especially banks, also have a role to play in this respect, by offering women entrepreneurs loans at affordable interest rates, with relatively long loan repayment periods.

On the other hand, Moroccan female entrepreneurs are encouraged to share their success stories across various platforms, including social media, with fellow women entrepreneurs to glean insights into best managerial practices. Furthermore, establishing entrepreneurial associations like the association of women entrepreneurs of Morocco (AFEM) is crucial for addressing legal and socio-cultural challenges to promote gender equality and remove barriers that prevent women from starting and growing their own businesses.

7.3. Limitations and Future Studies

As with all studies in the field of women’s entrepreneurship, the current study has its limitations, which open avenues for future studies. The first limitation of this study is its sole focus on a quantitative approach to examine the determinants of women’s entrepreneurial success in Morocco. As such, the quantitative method might not capture the depth and context of women’s experiences, hindering a comprehensive understanding of the factors contributing to their success.

As such, future work can embrace a complementary qualitative approach alongside a quantitative approach to provide a more comprehensive perspective on female entrepreneurial success in Morocco. Conducting in-depth interviews among Moroccan women entrepreneurs can unveil qualitative insights, such as personal motivations, challenges faced, and cultural influences, enriching the overall understanding of the factors influencing their success.

Another limitation associated with this research pertains to the number of variables chosen to elucidate the entrepreneurial success of Moroccan women, specifically, six variables encompassing three internal factors and three external factors. Hence, an enticing direction for future studies involves presenting a more intricate research model by integrating supplementary variables. This includes aspects such as digital literacy skills, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, self-confidence skills, and entrepreneurial mentorship.