Abstract

Background: The transition to adulthood is especially critical for young people who have been in the child protection system, as they face significant challenges in areas such as education, mental health, employment, and economics. Methods: This qualitative study examines the perceptions of 20 young adults from Spain who have exited the child protection system regarding their transition to adulthood. Structured interviews were conducted, transcribed, and analyzed using IRAMuTeQ software to identify thematic patterns. Results: The young adults reported inadequate preparation and a need for ongoing support, and they faced challenges in areas such as housing, employment, financial education, and mental health. They emphasized the importance of social and emotional support networks for successful adaptation. The results reveal a deficit in training programs and structural support, suggesting the need for a review of existing Spanish policies. Conclusions: Social educators play a crucial role in facilitating the transition to adulthood for young people who have been in protective systems in Spain, providing emotional support and resources to aid in their integration and autonomy. Effective coordination between institutional actors and Spanish society is vital to ensure a successful transition to adulthood.

1. Introduction

The transition to adulthood is a complex and crucial process for all young people, marked by profound societal changes and transformations in recent decades [1]. Initially understood through education and followed by entry into the labor market, this transition facilitates a successful passage into adulthood [2,3]. However, it poses particularly challenging hurdles for youth leaving the child welfare system, who often face this transition without the necessary ongoing support, quickly assuming multiple responsibilities without adequate preparation for this new phase [4,5]. Residential care often fails to provide adequate opportunities to acquire essential skills for transitioning into adulthood [6], with significant deficiencies in this preparation [7].

This study aims to investigate the specific challenges faced by young adults who have exited the child protection system in Spain and to explore their perceptions of the transition to adulthood. By focusing on this population, we address the gap in understanding the unique obstacles encountered by these individuals as they navigate the transition to independence. The research problem centers on identifying the key areas of difficulty and support needs during this period. The central research question guiding this study is as follows: “What are the main challenges and support needs experienced by young adults from Spain who have exited the child protection system as they transition to adulthood?”.

To address this question, the study employs a qualitative approach using structured interviews with a sample of 20 young Spanish adults who have recently exited the child protection system. The methodological framework includes thematic analysis using IRAMuTeQ software (version 0.7 alpha 2) to identify and interpret key patterns in the data. This study aims to provide insights into the areas where these individuals face significant challenges and to suggest improvements in support systems from the perspective of social education.

2. Literature and Context

2.1. Implications of the Transition to Adulthood for Formerly Fostered Youth

From a broader perspective, youth who have been in child protection systems face significant challenges as they transition to adulthood, characterized by the sudden assumption of roles and responsibilities related to autonomy, often without significant support figures [8,9]. This group shares the common traits of having been minors at social risk; residing in foster care centers under administrative guardianship; and having experienced psychological or physical abuse, which leaves them more vulnerable than their peers [10]. The transition to emancipation involves drastic changes in various aspects of their lives. Upon reaching legal adulthood, these young people find themselves in a situation of social vulnerability, lacking sufficient guarantees to live independently [11]. Consequently, they must navigate financial management, decision making, emotional control, and adapting to new homes and legal support networks within a very limited timeframe. This process can be overwhelming, exacerbated by their lack of prior experience in autonomous decision making and assumption of adult responsibilities [12,13].

In addition to practical challenges, emancipated youth often experience significant emotional vulnerability [13]. Fear, uncertainty, and confusion are common emotions due to the lack of stable support networks and the absence of adult role models to guide them during this critical stage of their lives [14]. This situation can contribute to the development of mental health issues such as anxiety and depression, compounded by the emotional burden and stress inherent in the transition [10]. The lack of support during the transition of emancipated youth to adulthood represents a crucial factor negatively impacting their mental health and well-being. These young people face considerable difficulties, including housing instability, unemployment, and limitations in accessing basic services such as health care and education [15,16,17]. An alarming proportion of emancipated youth experience psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress [10,18]. These disorders are exacerbated by chronic stress stemming from the lack of emotional and structural support during the transition to adulthood. Uncertainty about housing, economic insecurity, and the absence of consistent support figures contribute to an emotionally unstable environment, increasing the vulnerability of these youth to mental health problems [19]. Moreover, adverse childhood and adolescent experiences such as abandonment, abuse, or neglect can leave profound psychological scars that persist into adulthood, especially in the absence of adequate psychosocial support interventions [13,14]. Psychosocial interventions play a crucial role in mitigating these adverse effects. By addressing both the psychological and social dimensions of their experiences, these interventions can enhance coping mechanisms, increase self-esteem, and foster resilience among youth exiting the care system [13,14,20]. Resilience is closely linked to the psychological well-being of these youth [21,22,23]. Moreover, greater resilience correlates with lower levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, as these indicators decrease in the face of resilience processes, thereby promoting well-being [24,25]. Therefore, it is crucial to implement specific interventions that adequately support these youth during their emancipation process.

2.2. Implications of the Transition to Adulthood in Europe: The Case of Spain

The transition to adulthood has evolved significantly in recent decades. Today, this transition is characterized by its diversity and a divergence from a uniform process of emancipation [26,27]. In Western societies, there is a general trend towards a prolonged transition to adulthood, resulting in extended dependence on family support [28]. Young people in Spain, along with those in Italy, are more likely to spend most of their youth living with their families [29], in contrast to countries such as Sweden, France, the Netherlands, and Germany, where the average age of leaving the parental home is earlier [30]. All these countries have protective systems that include residential placements for the care of minors [31,32]. In recent years, there has been a shift in mindset with the primary goal of supporting and guiding youth in care towards achieving autonomy [33].

In Spain, most young people experience the transition to adulthood within the family context, making it a slow, gradual process with supportive structures [34]. However, those in residential care are often required to undergo this process much more quickly [35]. Spain has one of the lowest rates of emancipation in Europe, at 16.75%, meaning that approximately 17 out of every 100 young people aged 16 to 29 live outside their family home [36]. This situation is particularly problematic because, while some youth can rely on family support and remain in the family home until nearly 30 years old [37], others must face society independently as soon as they turn 18 [38]. Migrant youth, mainly from Morocco, face additional challenges such as schooling, language barriers, and difficulties accessing the labor market [39,40]. It is during residential care that factors promoting social inclusion must be developed. Law 26/2015 (art. 22bis) [41] stipulates that public entities must offer independent living preparation programs in the two years preceding adulthood. This is a significant issue for these youth, who must leave the care system upon reaching adulthood (18 years old in Spain) [42]. The crucial transition to adulthood occurs in a rapid and forced manner. Therefore, the exit from residential care should be conducted through a planned intervention that includes the participation of the youth themselves [43].

2.3. Social–Educational Work with Formerly Fostered Youth: Implications for Social Education

Social education, alongside other social disciplines, plays an essential role in supporting youth transitioning from foster care to emancipation. From the age of 15, professionals in this field focus on preparing these youth for independent living, teaching autonomy skills, and providing necessary tools for successful integration outside the protection system [14,44]. Additionally, educators offer emotional support [8]. During this preparation, the Individual Educational Project (IEP) is used to establish specific goals, such as decision making, social skills development, and fostering responsibility [8,14]. In addition to teaching practical skills, it is crucial to address the emotional aspects of these youth during the transition. Many of them experience significant emotional vulnerabilities due to the lack of ongoing support and the disruption of stable reference figures [13,14]. The IEP should include a comprehensive emancipation plan that incorporates support relationship planning, community connections, education, and life skills development [45]. These processes must be flexible and tailored to the needs of each at-risk youth [46,47]. Regarding programs and policies designed to support these youth, there is a need to implement effective strategies addressing both their practical and emotional needs. Emphasis is placed on integrated programs that combine vocational training, psychological support, and community support networks to improve emancipation outcomes [13].

2.4. Social Representations for Enhancing Social Reality

According to the theory of social representations, communication enables members of a society to understand, create, and transform a dynamic reality, to which they attempt to assign certain regularities [48]. This theory posits that a social representation allows individuals to prioritize, select, and retain significant aspects of ideological discourse based on their interactions with the environment. These representations have a distinctive structure and contribute to the construction of a compact explanatory and evaluative model of the environment, which influences the individual. This process of reconstructing and reproducing reality provides meaning and operational guidance for social life, including behavioral scripts, attitudes, and ideologies [49]. Through cognitive frameworks shaped by social interactions, individuals form their own unique mental representations. Consequently, they create social representations that function as structured systems of knowledge, each with its own logic and language, reflecting not just subjective opinions but the actual reality of a phenomenon [50].

To understand social reality and how individuals experience it, it is essential to inquire about their personal experiences. Therefore, this study is grounded in exploring the perceptions and reflections of young people who have been in residential care centers in Spain, aiming to gain firsthand insight into their transition to adulthood. It seeks to understand how they have faced this reality, what they have lacked, what resources and strategies they need to improve their situation, and how socio-educational interventions can be developed and implemented to enhance their integration into society.

3. Materials and Methods

A qualitative and exploratory research study was conducted; this methodology is suitable for delving into the details of a new, specific, or open reality, highlighting its defining elements and providing crucial information for social improvement [51]. In this study, individual interviews were employed as the primary method for data collection. The interviews were conducted with young individuals who had been in the care of the child protection system during their minor years. This methodology was chosen to explore in depth the personal experiences and perceptions of these youths regarding their transition to adulthood and the challenges they faced.

The theory of social representations was employed, which explores how groups construct and share knowledge and meanings about a shared topic of interest. This theory is based on the notion that social representations emerge from collective practices of generating and disseminating information within a social group [52]. Social representations play a crucial role in the perception and experience of reality among emancipated youth, both during their time under protection and after leaving the care center. Lacroix [53] and Boutanquoi [54] have investigated the transition to adulthood of these young individuals who have exited child welfare. These studies have relied on qualitative approaches to explore social representations among youth in specific foster-care and transition-to-adulthood contexts.

For the analysis of the data obtained from the interviews, lexical analysis using the Reinert method was employed. This approach focuses on organizing discourses through logically structured words, promoting coherence in the collected testimonies [55,56]. Bryman [57] suggests that lexical analysis is a powerful tool for unraveling hidden thematic patterns in qualitative data, enabling a deeper and more nuanced interpretation. Thus, a detailed and qualified interpretation of testimonies was achieved, allowing for a comprehensive observation of the complete experiences and perspectives of emancipated youth.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria with reference number CEIH-2024-09.

3.1. Measure

A structured questionnaire was designed for data collection, comprising sociodemographic questions (age, gender, employment status, educational level) and open-ended textual questions related to the research objectives. These questions included the following: “What has been your experience upon leaving the center?” “What have been the biggest challenges you have faced?” “What have you done to overcome the challenges you encountered?”

3.2. Participants

In the present study, the sample consisted of 20 emancipated youth from Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain. The sample selection was intentional, utilizing the snowball sampling technique, which facilitated the identification and recruitment of relevant participants and ensured a diversity of experiences and perspectives in the data collection process. The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. The gender distribution showed that 45% of the participants were male and 55% were female, with an average age of 20.75 years. Regarding educational background, 15% of the youth had completed basic vocational training, 65% had completed Compulsory Secondary Education or vocational training at a medium level, and 20% had completed high school or university studies. Concerning their employment status, 55% of the participants were currently employed, while the remaining 45% were not working.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample.

3.3. Procedure

The interviews were conducted in person. Before participation, the research objectives were thoroughly explained to the young individuals, and assurances of confidentiality and anonymity regarding their responses were provided. Informed consent was obtained for recording the interviews, which were subsequently transcribed. Each interview lasted approximately 40 min and took place in a calm and confidential environment, with the locations chosen by the interviewees, between 10 April and 15 May 2024.

Subsequently, the textual (open-ended) variables were refined for the analysis of social representations. The final corpus comprised 20 texts, consisting of 351 text segments and totaling 7166 occurrences of 1275 different forms, including 688 hapaxes (words appearing only once). A specific subcorpus was created according to the research objective: to explore the experiences of youth who have been through the protection system, the challenges they faced, and how they addressed these challenges during their transition to adulthood. This subcorpus consisted of 169 text segments with 3431 occurrences of 815 forms.

3.4. Data Analysis

Initially, the samples were characterized through a frequency analysis and distribution of sociodemographic variables using SPSS software (version 25) [58]. This initial step was crucial for understanding the participants’ specific characteristics and accurately contextualizing subsequent findings [59].

To deepen our understanding of the transition experiences of young people leaving the protection system, a series of interrelated analyses were conducted. Firstly, a similarity analysis was performed to identify the most recurrent words and how these words cluster together. This method, guided by Benzécri’s [60] recommendations on multivariate analysis of textual data, provides insight into recurring terms and their organization into meaningful clusters.

Following this, a lexical analysis of the subcorpus was carried out using the Reinert method, which focuses on uncovering social representations. This approach posits that reality is verbally constructed through “lexical worlds”—sets of words that form coherent segments of discourse, reflecting shared social representations on specific topics [61]. The analysis was facilitated using IRAMuTeQ software (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires), version 0.7 Alpha 2, which allowed a detailed exploration of the structure and organization of these lexical worlds [62].

In this comprehensive analysis, both lemmas and full words—including nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs—were examined. Descending Hierarchical Analysis (DHA) and Correspondence Factor Analysis (CFA) were employed to provide a nuanced representation of the data. The CFA accurately mapped the words and the positioning of classes on a Cartesian plane, based on the frequencies and correspondence values of each word in the corpus. This mapping visualized the vocabulary of each class within its semantic context, highlighting the relationships between different classes or social representations [63,64].

The DHA further classified and grouped text segments into classes, identifying the most significant words using the chi-square criterion, with a margin of error below 0.05. The results were visualized through a dendrogram, which illustrated the total percentage of segments included in each class and the richness of lexical relationships within them [64]. A qualitative assessment of each class was then conducted, based on the main words, related text segments, and their corresponding semantic context [65].

These analytical methods—similarity analysis, lexical analysis, and Descending Hierarchical Analysis (DHA)—are interrelated and complementary, collectively contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the complex lexical and semantic patterns in the discourses of youth transitioning out of the protection system. This integrated approach offers a cohesive framework for examining the social representations underlying their experiences.

4. Results

4.1. Similarity Analysis

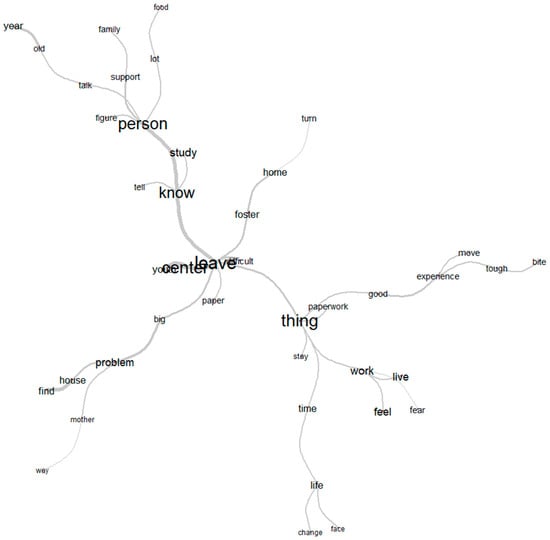

The similarity analysis (Figure 1) reveals a central core composed of the words “leave”, “know”, “person”, and “thing”. These words are connected to a series of subthemes reflecting the most significant experiences and challenges mentioned by the youth. The centrality of these words suggests that they are key concepts in the participants’ narratives.

Figure 1.

Similarity analysis.

The word “leave” is strongly associated with the experience of exiting the protection system. Young individuals frequently mention their “young” age as a significant factor, possibly indicating a lack of preparation due to their youth. Additionally, terms such as “big” and “paper” may refer to the magnitude of change and the bureaucracy involved in the departure process. This association underscores the importance of the moment of departure and the administrative challenges that the youths encounter.

Conversely, the word “know” emphasizes the importance of knowledge and information for these youth. Its connections with “tell” and “study” suggest that education and communication are crucial for understanding and managing their transition.

The word “person” relates to the need for support, both emotional and practical. Associations with “support”, “family”, and “figure” highlight the significance of having supportive figures and family networks for a successful transition.

The word “thing” pertains to concrete and everyday challenges, such as work (“work”) and paperwork (“paperwork”). Its connection with “feel” underscores the emotional impact of these challenges, indicating that practical concerns are intrinsically linked to the emotional well-being of young individuals. Issues related to housing and the role of family, especially the mother, also emerge as significant challenges. Additionally, feelings of “fear” and experiences of “life” emphasize the need for support in mental and emotional health.

The importance of support networks, including family and home, is critical for the adaptation and resilience of these young individuals. Key terms such as “support”, “family”, and “home” indicate that a strong support system can significantly impact the transition to adulthood.

The similarity analysis highlights several critical aspects of the transition process for emancipated youth. Recurring themes include a lack of preparation and ongoing support, with significant challenges in housing, employment, and mental health. Social and emotional support networks are crucial for their successful adaptation.

4.2. Factorial Analysis

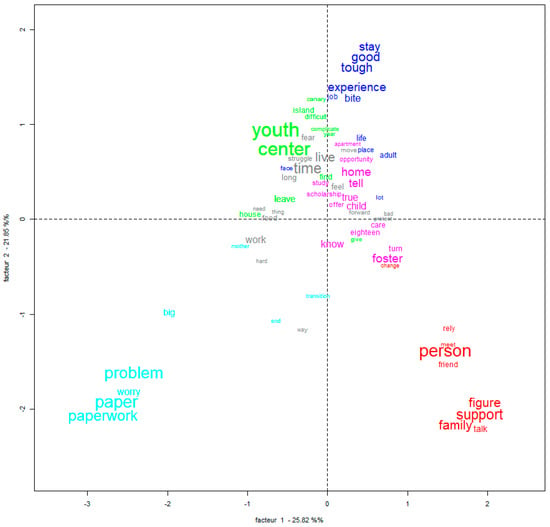

The factorial analysis (Figure 2) facilitates the visualization of word co-occurrence patterns within the corpus. Each cluster of words depicted in the figure is distinguished by different colors, each representing specific themes. The proximity between words illustrates thematic relationships, aiding in the comprehension and organization of ideas.

Figure 2.

Factorial analysis.

The blue cluster, positioned in the upper right quadrant, encompasses the words “stay”, “good”, “tough”, and “experience”. This cluster reflects experiences of persistence and resilience. The words “stay” and “good” suggest positivity and stability, while “tough” and “experience” indicate that, despite challenges, young individuals manage to endure. This cluster highlights their capacity to face and overcome adversities, emphasizing the significance of resilience during their transition.

The green cluster, located centrally, includes the words “youth”, “center”, “live”, “time”, “fear”, and “island”. This cluster focuses on the daily life and emotions of youth both within and outside protection centers. “Youth” and “center” refer to their time in the system, whereas “live” and “time” reflect their adjustment to life post-exit. The terms “fear” and “island” suggest feelings of isolation and concerns they experience. This cluster underscores the emotional and temporal aspects of transitioning from institutional care to independent living.

The purple cluster, situated to the right of center, comprises the words “home”, “tell”, “foster”, “child”, and “know”. This cluster highlights family interactions and the requisite knowledge for transition. “Home” and “foster” denote the family and foster care environment, while “tell” and “know” emphasize the importance of communication and information. The word “child” reflects a focus on youth and the need for guidance. This cluster underscores the importance of continuity and family support in achieving autonomy.

The red cluster, located in the lower right quadrant, includes the words “person”, “support”, “family”, “figure”, and “talk”. This cluster emphasizes the significance of personal relationships and social support. “Person”, “support”, and “family” highlight the role of support figures and familial networks, while “figure” and “talk” point to the necessity of communication and the presence of mentors or significant individuals. This cluster demonstrates that emotional and social support are crucial for a successful transition to adulthood.

The light blue cluster, found in the lower left quadrant, contains the words “problem”, “paper”, and “paperwork”. This cluster underscores the bureaucratic and practical challenges faced by young individuals. The terms “problem”, “paper”, and “paperwork” indicate that administrative hurdles are significant obstacles in their transition. This group highlights the need to streamline bureaucratic processes and provide administrative support to aid the integration of young people into society.

Factor 1 can be interpreted as an axis of positive versus negative experiences. Clusters on the right side (blue and red) reflect more positive and supportive aspects, while clusters on the left side (light blue and some words from the green) indicate challenges and negative experiences.

Factor 2 represents the continuity versus discontinuity of experiences. Clusters in the upper part (blue and some words from the green) suggest greater continuity and stability, whereas clusters in the lower part (light blue and purple) reflect abrupt transitions and challenges in adaptation.

This factor can also be interpreted in terms of support versus autonomy. Clusters on the right (red and purple) signify greater reliance on social and familial support, while clusters on the left (light blue and some words from the green) reflect a greater need for autonomy and facing challenges independently.

The factorial analysis reveals that the transition from care to adulthood involves a series of practical, emotional, and bureaucratic challenges. Themes of resilience and the capacity to endure adversity are prevalent, alongside the critical role of social and familial support networks. Administrative difficulties and the necessity for guidance and knowledge are significant obstacles that need addressing to facilitate a successful transition.

4.3. Descending Hierarchical Classification on the Subcorpus of Experiences, Challenges, and Coping Strategies of Young People Who Have Gone through the Protection System

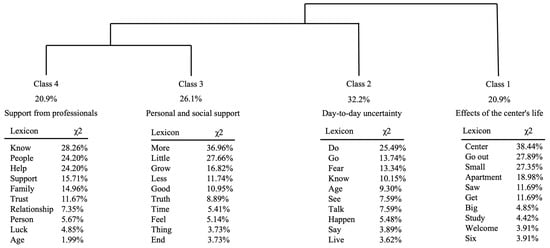

The Descending Hierarchical Analysis (DHA) of the experiences of young people leaving the protection system has identified four distinct classes. These classes reflect their experiences both within the center and the challenges and coping strategies encountered after leaving it. The dendrogram (Figure 3) provides a structured overview of how these themes are grouped based on their similarity.

Figure 3.

Dendrogram of the descending hierarchical classification of the departure process and coping with life outside the center, including words whose relationship criterion with the class (X2) was significant (p < 0.005).

The first dimension encompasses Class 1, which addresses historical aspects related to the time spent in the protection center. The second dimension includes Classes 2, 3, and 4, focusing on experiences after leaving the center. Specifically, Classes 3 and 4 reflect emotional and personal aspects, while Class 2 deals with operational issues, and Class 1 pertains to the consequences of life in the center.

Class 1, titled “Effects of the center’s life” (20.9% of text segments), centers on the immediate challenges and direct repercussions faced by young people after exiting the center. This class highlights difficulties in securing housing and employment, which are exacerbated by factors such as racism and a lack of resources. A representative quote from this class is as follows: “The biggest problems I had were related to housing when I left the youth center. I was looking for a place to live, but because of racism, I had a lot of trouble finding a rental” (112.35%). Another illustrative quote is as follows: “Mainly it was finding a house because when I left the center, I found myself on the street. So, I had to also find a job to make money, besides finding a place to sleep” (67.84%). Additionally, economic issues are mentioned, as in the following quote: “Of my seven siblings, six of us were in the youth center and we were all promised a stipend” (69.71%).

The second class, titled “Day-to-Day Uncertainty” (32.2% of text segments), reflects the confusion and disorientation experienced by young people as they navigate daily tasks without the institutional support to which they were accustomed. Quotes from this class reveal a lack of knowledge and practical skills. Examples include the following: “Doing this is like this when you turn eighteen; I had to handle the registration and didn’t even know how to visit the doctor” (64.02%). “Go to the bank and they should inform you when you leave. I didn’t know what to do, what do I do?” (29.38%). “I had to deal with paperwork, schedule appointments, and go to immigration to sort it out” (39.23%). They also speak of fear in this new situation, as illustrated by quotes such as the following: “Overcoming fear and feeling secure in doing things, being reliable at work, not missing” (38.83%).

The third class, labeled “Personal and Social Support” (26.1% of text segments), focuses on the emotional responses and personal strategies employed by young individuals to adapt to their new circumstances. This category includes statements such as the following: “In this specific situation, I felt somewhat isolated, which I consider to be a significant challenge” (81.46%); “I have faced difficulties in dealing with more adverse circumstances, which has required me to be more resilient” (67.27%); “At that age, you have to mature a bit more quickly, but yes, that’s the truth” (73.53%).

The fourth class, referred to as “Professional Support” (20.9% of text segments), encompasses contributions related to professional assistance and guidance. This class includes observations such as the following: “At this stage, I did not have the opportunity to establish significant interpersonal relationships, which impacted my level of trust and comfort” (63.33%); “I received notable support and guidance in making relevant decisions, which alleviated the feeling of loneliness that I might have otherwise experienced” (22.91%); “I experienced psychological problems and had a period of anxiety caused by a lack of support” (62.96%); “I was lucky because if it hadn’t been for the help this man gave us, I can’t say what might have happened to me” (32.76%).

5. Discussion

The objective of the present study was to explore the perceptions and reflections of young Spanish individuals who have exited the child protection system, with the aim of identifying the primary challenges they face in their transition to adulthood and gaining a deeper understanding of the realities they encounter upon leaving the system. The central research question was as follows: “What are the main challenges and support needs experienced by young adults from Spain who have exited the child protection system as they transition to adulthood?”.

5.1. Similarity Analysis

The similarity analysis of narratives from emancipated Spanish youths reveals several critical aspects that shape their transition to adulthood. The core words “leave”, “know”, “person”, and “thing” highlight key elements in the participants’ experiences, indicating the significance of leaving the protection system, the need for knowledge, the importance of personal support, and the challenges of everyday life. This analysis underscores the complexity of the transition process, suggesting that while some youths are concerned with the logistics and emotional impact of leaving the system, others focus on acquiring the necessary knowledge and support to navigate their new realities. For this reason, Villa [66] emphasizes the need for pre-transition preparation programs and structured post-emancipation support to ensure a successful transition for Spanish youth who have exited child protection centers.

The findings suggest that the transition from care is often accompanied by a sense of unpreparedness, as indicated by the frequent mention of “young” in association with “leave”. This aligns with existing literature that highlights the abrupt nature of transitions for youths in care, who often lack the gradual preparation enjoyed by their peers in more traditional family settings [35]. Bureaucratic challenges, evidenced by words such as “big” and “paper”, further complicate this process, indicating the need for more efficient administrative support. Although this preparation varies for everyone, most argue that, in general, they are not fully prepared [67], as it should be remembered that this population has experienced significant deficits in their development [68].

Additionally, the analysis highlights the critical role of support networks. The emphasis on words such as “person”, “support”, “family”, and “figure” reflects the importance of having stable and supportive relationships during this transition. This finding is consistent with the broader literature, which emphasizes the role of social capital and emotional support in mitigating the challenges faced by emancipated youths [34]. The emotional and practical dimensions captured by the word “thing” underscore the intertwined nature of practical challenges and emotional well-being, emphasizing the need for holistic support systems that address both aspects simultaneously. Emotional support and personal coping strategies emerge as crucial factors for adaptation. Resilience and the ability to face adversity are strongly influenced by the quality of social and family support networks. Bravo and Del Valle [69] emphasize that these youths exhibit high resilience and adaptability in adverse situations. Consequently, programs aimed at this group should foster these strengths, building self-confidence and coping skills to overcome obstacles and achieve a successful transition to adulthood [70]. Other Spanish studies highlight a lack of social support when these young people exit the child protection system [71,72], noting their scarcity of adult role models outside the institution, with social support often provided by other youths previously known within the protection system. Therefore, it is crucial to prioritize the development of a supportive social network, including both adults and peers, in programs designed to prepare these young Spaniards for adulthood [72,73].

5.2. Factorial Analysis

The factorial analysis provides a deeper understanding of the thematic clusters that shape the experiences of these Spanish youths. The identified clusters, such as “resilience and persistence”, “daily life and emotions”, “family and foster dynamics”, and “bureaucratic challenges”, offer a nuanced view of the various dimensions of the transition process. The analysis suggests that positive and supportive experiences (as seen in the blue and red clusters) are associated with greater resilience and emotional stability, while challenges and negative experiences (light blue clusters and some words from the green) are linked with difficulties in achieving autonomy and stability.

This analysis aligns with the conceptual framework of resilience, which posits that supportive relationships and positive experiences can buffer the negative impacts of adversity [33]. In the study by González et al. [74], it was found that social support networks positively impacted participants’ resilience dispositions. Having significant individuals across various contexts aids in overcoming risks and fosters a positive outlook on life, including goal setting [75]. Furthermore, resilience has positive effects on behavior, as it helps mitigate the impact of risk factors [74]. The clusters highlighting family interactions and bureaucratic challenges underscore the importance of continuity and the need for effective communication and information. The focus on bureaucratic obstacles suggests a critical area for policy intervention, as simplifying these processes could significantly ease the transition for these youths.

5.3. Descending Hierarchical Classification

The Descending Hierarchical Analysis (DHA) further categorizes the experiences of emancipated youths into four distinct classes, providing a structured view of the challenges and coping strategies they employ. The differentiation between experiences within the protection system and those encountered post-exit reveals a clear division in the nature of the challenges faced.

Class 1, “Effects of Life in the Center”, highlights the immediate challenges related to housing and employment, exacerbated by factors such as racism and lack of resources. This finding suggests that Spanish youths leaving care are often ill prepared for the realities of independent living, facing significant barriers to securing stable housing and employment. This aligns with the broader literature on youths in care, which frequently identifies housing stability as a critical challenge [42]. It is important to note that not living with family at age 18 can lead to stigma in Spanish society, which remains largely unaware of the realities faced by these youths [68]. Therefore, labor market insertion represents a major concern for this group due to insufficient training and work experience. Goig and Martínez [76] highlight the importance of vocational training and supported employment policies to increase job opportunities for these youths. Implementing training programs that provide practical skills and technical knowledge, as well as promoting policies that incentivize companies to hire young people leaving the care system, is crucial for facilitating their integration and professional development [77]. Moreover, academic training is pivotal for transitioning into active life and achieving stability and advancement in the job market [78]. Enhanced supervision and education can promote well-being, job security, and financial stability among these youths [79].

Class 2, “Day-to-Day Uncertainty”, reflects the confusion and disorientation experienced by these youths as they navigate daily tasks without the institutional support they were accustomed to. This lack of practical knowledge and skills underscores the need for comprehensive life skills training before youths leave care, as well as ongoing support to aid in their adaptation to independent life. In the realm of social relationships and adult support, these youths often lack a strong support network, which exacerbates their situation. They emphasize the importance of forming bonds with mentors and community networks that can offer guidance and emotional support [80]. These connections are essential for young Spanish people to develop stable and trusting relationships, helping them feel accompanied and supported on their path to autonomy [81]. Strengthening social bonds and developing support networks are crucial to ensuring the success of these youths’ emancipation [82]. To expand this support network, it is essential to work on social and emotional skills [69].

Class 3, “Personal and Social Support”, emphasizes the emotional responses and coping strategies employed by the youths, highlighting the importance of resilience and emotional support networks. This class suggests that while some youths are able to develop adaptive strategies, others may struggle without adequate emotional and social support, underscoring the need for targeted interventions to enhance these capabilities. Youths exiting the care system face numerous mental health challenges stemming from abandonment or abuse experienced throughout their lives. These difficulties significantly impact their successful transition into adulthood. The Federation of Entities with Assisted Projects and Housing (FEPA) [9] emphasizes the need for mental health programs that provide continuous emotional support after these young individuals leave the protection system. It is essential that these programs are accessible and designed to address specific traumas and emotional needs of young people leaving foster care, helping them develop emotional stability to cope with the challenges of adulthood [83]. The study by Campos et al. [84] found that for these Spanish youths, having someone who is genuinely interested in them significantly improves their well-being, regardless of the nature of the relationship, as the quality of the relationship is more important. It is known that Spanish youths who have exited the child protection system seek individuals who show a genuine interest in their lives, listen to them, and provide support [68].

Class 4, “Professional Support”, highlights the role of professional guidance in facilitating a smoother transition. This class underscores the variability in the quality and availability of professional support, suggesting that more consistent and accessible support services could significantly improve outcomes for these youths. From the perspective of social education, understanding these challenges is crucial for designing strategies and programs that facilitate their integration and autonomy [3]. These professionals play a crucial role in creating recreational spaces and intergenerational environments that contribute to the establishment of a supportive social network for these Spanish youths [72].

Economics is another critical area for the independence of Spanish youths leaving the foster care system. The lack of resources and financial management training places them in a vulnerable position. Ballester and Oliver [82] highlight the importance of providing economic support and financial management training to promote the autonomy of these youths through scholarship programs or emergency funds designated for this purpose. It is essential to teach them to effectively manage their finances, thereby equipping them with the skills necessary to handle their money and plan their economic future independently of their families [82].

From the standpoint of social education, continuous support and necessary resources provided by social educators are essential for facilitating the integration and autonomy of this group during their transition process. These professionals play a fundamental role in creating secure environments for these young people, developing social skills, and fostering resilience to face adult life [85]. As noted by Ochotorena [85], the support provided by social educators not only facilitates access to various services and resources but also offers crucial emotional and motivational support, making these youths feel valued and confident in their abilities to build a better future. Lemon et al. [86] emphasize that the emancipation of these youths can be more successful when a strong supportive relationship is established between professionals and the youths. However, these relationships must be based on effective support, including mentoring programs [45].

It is important to monitor youths leaving the protection system and provide long-term follow-up, coordinated with other institutions and agents [14,82]. Nevertheless, one must consider the risk factors associated with institutionalization, such as the instability and turnover of adult references due to staff changes, lack of training, or precarious contracts [87,88]. This should be taken into account when working with these young people.

Finally, it is pertinent to highlight perspectives and contributions from other studies that reinforce these conclusions, such as the research by Courtney et al. [89] and Stein [10], who have extensively analyzed the transitions of youths leaving foster care into adulthood and emphasized the importance of comprehensive policies to support them through this process. More importantly, it is crucial to consider the particular context of Spain, where emancipation increasingly occurs at later ages, yet these youths begin their adulthood at 18 years old outside the protection system [42,90].

Based on the above, the following are highlighted as the primary challenges and support needs experienced by Spanish youths who have been in child protection centers: lack of preparation for independent living; insufficient social and emotional support both within and outside the center; access to housing, education, and employment; economic sustenance; and interpersonal relationship difficulties. Given this context, it is essential to design socio-educational policies that facilitate a smoother transition to adulthood for these Spanish youths.

6. Conclusions

This study underscores the critical need for a comprehensive approach that includes pre-transition preparation, post-transition support, and targeted policy interventions to enhance the well-being of Spanish youth exiting the child protection system. The findings highlight the importance of developing robust social and emotional support networks and strengthening resilience to ensure a successful transition to adulthood. Specifically, there is an urgent need for policies and programs that facilitate access to housing, employment, and mental health services, tailored to the unique challenges faced by these young individuals in Spain.

The role of social education specifically and socio-educational intervention in general is fundamental in this context, as it helps create supportive environments, fosters essential social skills, and promotes resilience. These strategies ensure that young adults feel valued and empowered to navigate their adult lives with confidence and autonomy.

However, this study has certain limitations. The sample size of interviewed individuals was relatively small, and the research was conducted in only one autonomous community in Spain. These factors may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should expand the sample size and explore experiences across multiple regions to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and support needs of young people transitioning from the protection system throughout Spain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A.R., M.B.S. and P.M.A.; data curation, P.A.R.; formal analysis, P.M.A. and P.A.R.; methodology, P.A.R. and M.B.S.; writing—original draft, P.M.A.; writing—review and editing, P.A.R. and P.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria with reference number CEIH-2024-09.

Informed Consent Statement

The authors declare that the respondents expressed their written informed consent to the survey.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rivera-Vargas, P.; Ferrante, L.; Herrera, G. Pedagogías del Conflicto para la Emancipación. Tensionando los Conocimientos Regulados y el Sentido Común en la Escuela. Rev. Int. Educ. Just. Soc. 2022, 11, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Bataller, S. Modos emergentes de transición a la vida adulta en el umbral del siglo XXI: Aproximación sucesiva, precariedad y desestructuración. Rev. Esp. Investig. Sociol. 1996, 75, 294–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, L. La transición a la Vida Adulta de los Jóvenes Extutelados. Estudio del Programa de Emancipación de la “Fundación de Solidaridad Amaranta”. 2019; pp. 1–71. Available online: http://dspace.uib.es/xmlui/handle/11201/150656 (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Courtney, M.E.; Hook, J.L. The potential educational benefits of extending foster care to young adults: Findings from a natural experiment. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 72, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melkman, E.P.; Benbenishty, R. Social support networks of care leavers: Mediating between childhood adversity and adult functioning. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 86, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.M.; Wojciak, A.S.; Cooley, M.E. The experience with independent living services for youth in care and those formerly in care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 84, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comasòlivas, A.; Sala, J.; Marzo, T. Los recursos residenciales para la transición hacia la vida adulta de los jóvenes tutelados en Cataluña. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. 2018, 31, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEPA (Federación de Entidades con Proyectos y Pisos Asistidos). Federation of Entities with Assisted Projects and Housing. La Emancipación de Jóvenes Tutelados y Extutelados en España; Federación de Entidades con Proyectos y Pisos Asistidos: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Volume 5, pp. 27–31. Available online: https://www.fepa18.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Mapa_emancipacion_FEPA.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Stein, M. Young People Leaving Care: Supporting Pathways to Adulthood; Jessica Kingsley Publishing: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, F.; Carrió, M. Construcció del Servei per a Joves Extutelats a les Illes Balears. In Anuari Joventut Illes Balears; Biblioteca general de Les Illes Balears: Illes Balears, Spain, 2018; pp. 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bàrbara, M. ¿Quién me ayuda a hacerme mayor? El acompañamiento socioducativo en la emancipación de los jóvenes extutelados. Educ. Soc. Rev. Interv. Socioeduc. 2009, 42, 61–72. Available online: http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3053571 (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Brady, B.; Dolan, P.; McGregor, C. Mentoring for Young People in Care and Leaving Care; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zamora, S.; Ferrer, V. Los jóvenes extutelados y su proceso de transición hacia la autonomía: Una investigación polifónica para la mejora. Rev. Educ. Soc. 2013, 17, 30. Available online: https://eduso.net/res/revista/17/miscelanea/los-jovenes-extutelados-y-su-proceso-de-transicion-hacia-la-autonomia-una-investigacion-polifonica-para-la-mejora (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Verulava, T.; Jorbenadze, R.; Bedianashvili, G.; Dangadze, B. Challenges faced by youth aging out of foster care: Homelessness, education and employment. Euromentor J. Stud. Educ. 2020, 11, 104–116. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R. The state of research on undergraduate Youth Formerly in Foster Care: A systematic review of the literature. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2019, 14, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, M.E.; Dworsky, A. Early outcomes for young adults transitioning from out-of-home care in the USA. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2006, 11, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Cohen, P.; Johnson, J.G.; Salzinger, S. A longitudinal analysis of risk factors for child maltreatment: Findings of a 17-year prospective study of officially recorded and self-reported child abuse and neglect. Child Abus. Negl. 1998, 22, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greeson, J. Foster Youth and the Transition to Adulthood: The theoretical and conceptual basis for natural mentoring. Emerg. Adulthood 2013, 1, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Esterri, J.; De-Juanas, A.; Goig-Martínez, R. Bienestar psicológico y resiliencia en jóvenes en riesgo social: Revisión sistemática. Vis. Rev. 2022, 12, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copolov, C.; Knowles, A.; Meyer, D. Exploring the predictors and mediators of personal wellbeing for young Hazaras with refugee backgrounds in Australia. Aust. J. Psychol. 2018, 70, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.; Said, G. Working with unaccompanied asylum-seeking young people: Cultural considerations and acceptability of a cognitive behavioural group approach. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2019, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Ziaian, T.; de Anstiss, H.; Baak, M. Ecologies of Resilience for Australian High School Students from Refugee Backgrounds: Quantitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.; Butler, C.; Cooper, K. Gender minority stress in trans and gender diverse adolescents and young people. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1182–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, A.R.; Zhou, C.; Bradford, M.C.; Salsman, J.M.; Sexton, K.; O’daffer, A.; Yi-Frazier, J.P. Assessment of the Promoting Resilience in Stress Management Intervention for Adolescent and Young Adult Survivors of Cancer at 2 Years: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2136039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Singly, F. Las formas de terminar y de no terminar la juventud. Rev. Estud. Juv. 2005, 71, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Requena, M. Familia, convivencia y dependencia entre los jóvenes españoles. Panor. Soc. 2006, 3, 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Höger, I.; Sjöblom, Y. Procedures when young people leave care: Views of 111 Swedish social services managers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 2452–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manacorda, M.; Moretti, E. Why do most Italian young men live with their parents? Intergenerational transfers and household structure. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2006, 4, 800–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Mínguez, A. The late transition to adulthood in Spain in a comparative perspective: The incidence of structural factors. Young Nord. J. Youth Res. 2012, 20, 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Artamonova, A.; Guerreiro, M.D.; Höjer, I. Time and context shaping the transition from out-of-home care to adulthood in Portugal. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 115, 105105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S.; Gabriel, T.; Bombach, C. Narratives on leaving care in Switzerland: Biographies and discourses in the 20th century. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2021, 26, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, A. Insights into structurally identical experiences of residential care alumni: The paradox of becoming autonomous in a residential care facility. Int. J. Child Youth Fam. Stud. 2018, 9, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montserrat, C.; Baena, M. Evaluación del proceso de emancipación de los jóvenes en acogimiento residencial o familiar. In Jóvenes que Construyen Futuros: De la Exclusión a la Inclusión Social; Ballester, L., Caride, J.A., Melendro, M., Montserrat, C., Eds.; Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2016; pp. 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, M. Young people aging out of care: The poverty of theory. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2006, 28, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio de la Emancipación. La Emancipación Juvenil en España. 2024. Available online: https://www.observatorioemancipacion.org/la-emancipacion-juvenil-en-espana-datos-generales/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Del Valle, J. Spain. In Young People’s Transitions from Care to Adulthood: International Research and Practice; Stein, M., Munro, E.R., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 2008; pp. 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, S. Foster care youth and the development of autonomy. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 32, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Salvador, I.; Muyor Rodríguez, J.; López San Luis, R. La emancipación de los jóvenes desde los centros de protección de menores: La visión profesional. OBETS. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2021, 16, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Belmonte, J.; López Meneses, E.; Vázquez Cano, E.; Fuentes Cabrera, A. Avanzando hacia la inclusión intercultural: Percepciones de los menores extranjeros no acompañados de centros educativos españoles. Rev. Nac. Int. Educ. Inclusiva 2019, 12, 331–350. Available online: http://revistaeducacioninclusiva.es/index.php/REI/article/view/482 (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Gobierno de España. Boletín Oficial del Estado. Ley 26/2015, de 28 de Julio, de Modificación del Sistema de Protección a la Infancia y a la Adolescencia. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 180, de 29 de Julio de 2015. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2015/BOE-A-2015-8470-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- López, M.; Santos, I.; Bravo, A.; Del Valle, J.F. El proceso de transición a la vida adulta de jóvenes acogidos en el sistema de protección infantil. Anales Psicol. 2013, 29, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncoso, C.; Verde-Diego, C. Transición a la vida adulta de jóvenes tutelados en el sistema de protección. Una revisión sistemática (2015–2021). Trab. Soc. Glob. Glob. Soc. Work 2022, 12, 26–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevillano, L.; Sanz, M. Percepciones de los profesionales sobre el acompañamiento socioeducativo en los recursos de transición a la vida adulta: Un análisis comparativo entre Andalucía y Cataluña. Rev. Esp. Educ. Comp. 2022, 41, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naccarato, T.; DeLorenzo, E. Transitional youth services: Practice implications from a systematic review. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2008, 25, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, M.E.; Valentine, E.J.; Skemer, M. Experimental evaluation of transitional living services for system-involved youth: Implications for policy and practice. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 96, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Santos, I.; Bravo, A.; del Valle, J.F. The process of transition to adulthood for youth in the childcare system. An. De Psicol. 2013, 29, 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovici, S. Psicología Social II; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, T.A. Ideología: Una Aproximación Multidisciplinaria; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, M.; Herrera, M. La representación social de los valores en el ámbito educativo. Investig. Y Postgrado 2007, 22, 261–305. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Introducing Research Methodology: A Beginner’s Guide to Doing a Research Project, 7th ed.; Sage: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovici, S. La Psicología de Las Minorías Activas; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, I. Passage à l’âge adulte des jeunes sortant de l’Aide sociale à l’enfance. Fiches Repères Obs. Jeun. Sport Vie Assoc. Éduc. Pop. 2020, 51, 1–2. Available online: https://injep.fr/publication/passage-a-lage-adulte-des-jeunes-sortant-de-laide-sociale-a-lenfance/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Boutanquoi, M. Compréhension des pratiques et représentations sociales: Le champ de la protection de l’enfance. Rev. Int. Educ. Fam. 2008, 24, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alba, M. El método ALCESTE y su aplicación al estudio de las representaciones sociales del espacio urbano: El caso de la ciudad de México. Papers Soc. Represent. 2004, 13, 1.1–1.20. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, E. El análisis crítico del discurso en el escenario educativo. Zona Próxima 2016, 25, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics para Windows; versión 25.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; Sage: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Benzécri, J.P. L’analyse des Données; Perse: Dunod, Scotland, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Reinert, M. Une méthode de classification descendante hiérarchique: Application à l’analyse lexicale par contexte. Cah. De L’analyse Des Données 1983, 8, 187–198. Available online: http://www.numdam.org/item/CAD_1983__8_2_187_0/ (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Grigsby, E. Analyzing Politics: An Introduction to Political Science; Cengage Advantage Books; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- López, P.; Fachelli, S. Análisis Factorial. In Metodología de la Investigación Social Cuantitativa; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Bellaterra, Spain, 2016; pp. 5–134. Available online: http://ddd.uab.cat/record/142928 (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Camargo, B.V.; Justo, A.M. IRAMUTEQ: Um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Rev. Temas Em Psicol. 2013, 21, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenacre, M.J. Correspondence Analysis in Practice, 2nd ed.; Chapman & Hall/CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, A. Jóvenes extutelados: El reto de Emanciparse hoy en día. Debats Catalunya Social. Propues. Desde El Terc. Sect. 2015, 41, 1–36. Available online: https://www.fepa18.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Dossier-41_ESP_ene2015_DEF.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Cuenca, M.E.; Campos, G.; Goig, R.M. El tránsito a la vida adulta de los jóvenes en acogimiento residencial: El rol de la familia. Educación XXI 2018, 21, 321–343. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/706/70653466015.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2024). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Campos, G. Transición a la Vida Adulta de los Jóvenes Acogidos en Residencias de Protección. Programa de Doctorado en Desarrollo, Aprendizaje y Educación. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma Madrid, Facultad de Psicología, Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, A.; Del Valle, J.F. Las redes de apoyo social de los adolescentes acogidos en residencias de protección. Un análisis comparativo con población normativa. Psicothema 2003, 15, 136–142. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Juanas, A.; García-Castilla, F.J.; Galán-Casado, D.; Díaz-Esterri, J. Time management of young people in social difficulties: Proposals for improvement in their life trajectories. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Esterri, J.; Goig-Martínez, R.; De-Juanas, A. Espacios intergeneracionales de ocio y redes de apoyo social en jóvenes egresados del sistema de protección. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2021, 13, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morese, R.; Palermo, S.; Defedele, M.; Nervo, J.; Borraccinno, A. Vulnerability and social exclusion: Risk in adolescence and old age. In The New Form of Social Exclusion; Morese, R., Palermo, S., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- González, S.; Gaxiola, J.; Valenzuela, E. Apoyo social y resiliencia: Predictores de bienestar psicológico en adolescentes con suceso de vida estresante. Psicol. Salud 2018, 28, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaxiola, J.C.; Frías, A.M.; Hurtado, A.M.F.; Salcido, N.L.C.; Figueroa, F.M. Validación del Inventario de Resiliencia (IRES) en una población del noroeste de México. Enseñanza E Investig. En Psicol. 2011, 16, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Goig, R.; Martínez, I. La transición a la vida adulta de los jóvenes extutelados. Una mirada hacia la dimensión “vida residencial”. Bordón Rev. Esp. Pedagog. 2019, 71, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Y.; Gabrielli, J.; Tunno, A.; Hambrick, E. Strategies for longitudinal Research with youth in foster care: A demonstration of methods, barriers, and innovations. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jariot, M.; Sala, J.; Arnau, L. Jóvenes tutelados y transición a la vida independiente: Indicadores de éxito. REOP-Rev. Esp. Orient. Psicopedag. 2015, 26, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häggman-Laitila, A.; Salokekkilä, P.; Karki, S. Transition to adult life of young people leaving foster care: A qualitative systematic review. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 95, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raithel, J.; Yates, M.; Dworsky, A.; Schretzman, M.; Welshimer, W. Partnering to leverage multiple data sources: Preliminary findings from a supportive housing impact study. Child Welf. 2015, 94, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois, D.L.; Silverthorn, N. Natural mentoring relationships and adolescent health: Evidence from a national study. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, L.; Oliver, J.L. Emancipació Dels Joves Extutelats: Situación Actual i Reptes de Futur; Anuari de l’Educació de les Illes Balears: Fundació Guillem Cifre de Colonya: Illes Balears, Spain, 2016; pp. 281–295. [Google Scholar]

- Pecora, P.; Williams, J.; Kessler, R.; Hiripi, E.; O´Brien, K.; Emerson, J.; Herrick, M.; Torres, D. Assessing the educational achievements of adults who were formerly placed in family foster care. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2006, 11, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, G.; Goig, R.; Cuenca, E. La importancia de la red de apoyo social para la emancipación de jóvenes en acogimiento residencial. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 18, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochotorena, J. La intervención psicosocial en protección infantil en España: Evolución y perspectivas. Pap. Psicol. 2009, 30, 4–12. Available online: https://www.papelesdelpsicologo.es/pdf/1651.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Lemon, K.; Hines, A.M.; Merdinger, J. From foster care to young adulthood: The role of independent living programs in supporting successful transitions. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2005, 27, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groinig, M.; Sting, S. Educational pathways in and out of child and youth care. The importance of orientation frameworks that guide care leavers’ actions along their educational pathway. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 101, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, L.E.; Alonso, E.; Feliciano, L. Trayectorias laborales y competencias de empleabilidad de jóvenes nacionales e inmigrantes en riesgo de exclusión social. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2018, 29, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, M.; Dworsky, A.; Lee, J.; Raap, M. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 23 and 24. Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago 2010. Available online: https://www.chapinhall.org/wp-content/uploads/Midwest-Eval-Outcomes-at-Age-23-and-24.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Sala-Roca, J.; Villalba, A.; Jariot, M.; Arnau, L. Socialization process and social support networks of out-of-care youngsters. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).