Determining the Factors Influencing the Behavioral Intention of Job-Seeking Filipinos to Career Shift and Greener Pasture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection Procedure

3.2. Questionnaire

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Measurement of the Variables

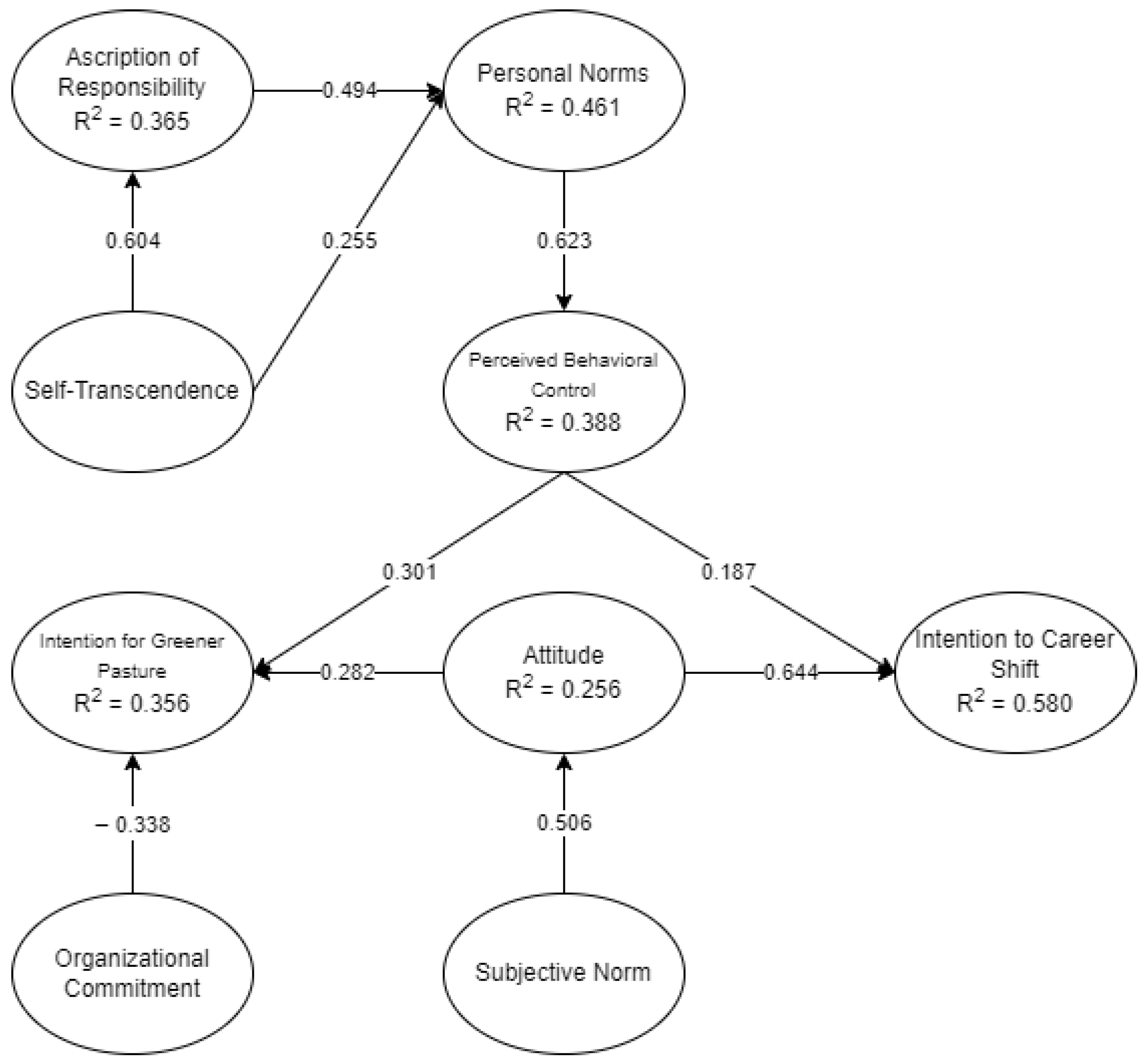

4.2. Model Output

4.3. Reliability and Validity

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical and Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

- The sample size and its diversity might limit the generalizability of findings, suggesting a need for larger, more diverse samples. The percentage-wise output of the data collected represented a sample for generalized insight, but the diversity when it comes to profession, age, and salary may raise other findings. This is because personal beliefs and professional goals may vary even if the collected sample represents those within the telecom, BPO, and government agencies. It is suggested that a longitudinal or experimental investigation to understand personal values and professional goals may be considered.

- The study’s questionnaire in English could benefit from translation into Filipino to accommodate a wider range of respondents, as Wenz et al. [129] examined the effect of language proficiency on survey data quality. Despite the country being diverse in the English language, it is worth noting that older and less educated respondents are more prone to providing lower-quality responses if distributed with these types of questionnaires.

- The questionnaires were distributed through online channels and social media platforms. As Dwivedi et al. [130] stated, one of the drawbacks of social media is that it can lead to the misrepresentation of information. To address this limitation, future research endeavors could adopt a mixed-methods approach, incorporating qualitative interviews or observational research. The use of a cross-sectional strategy in the study restricts its capability to create causal relationships; in addition, subsequent studies might explore longitudinal or experimental designs for a more comprehensive understanding.

- Self-report measures may introduce bias, so complementing them with other data sources such as collective demographic characteristics, statistical analyses with other countries, and even cross-cultural examination could enhance the study’s robustness.

- Additionally, values and career intentions can evolve over time, which this study does not account for, making long-term studies valuable. Recognizing these limitations is valuable for future studies and research to advance and broaden our comprehension of these complex dynamics.

- Lastly, tools to elucidate similarity among measure items, variables, and demographic characteristics may be performed using machine learning and deep learning algorithms [131]. It is suggested that future researchers may consider this analysis as a fuzzy decision-making process [132], or even fuzzy decision-making for prediction [133].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Codes | Constructs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Transcendence | ST1 | I feel that there should be equal opportunities for all | Ghazali et al. [32] |

| ST2 | I have the compassion to care for my family | ||

| ST3 | I have the capability to help my family | ||

| ST4 | I have the capability to help my friends | ||

| Ascription of Responsibility | AR1 | I share responsibility for having a job | Fenitra et al. [78]; Hoeksma et al. [79] |

| AR2 | I sense collective responsibility for societal welfare issues | ||

| AR3 | I play a significant role in addressing societal welfare problems | ||

| AR4 | Individually, people can contribute to job creation | ||

| Personal Norms | PN1 | It is my obligation to find a job | Fenitra et al. [78] |

| PN2 | People like me should find a job | ||

| PN3 | It is my own obligation to secure a job | ||

| PN4 | I would experience guilt if I couldn’t secure a job | ||

| PN5 | Having a job made me think of myself as a responsible human being | ||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC1 | I possess sufficient body strength to have the job I want | Fenitra et al. [78] |

| PBC2 | My time would be convenient working in a job I want | ||

| PBC3 | I have the necessary skills for the job I want | ||

| PBC4 | The career path I will take is my own choice | ||

| Subjective Norm | SN1 | The individuals who hold significance in my life has a job | Fenitra et al. [78]; Ghazali et al. [32] |

| SN2 | My family and friends would disapprove if I do not have a job | ||

| SN3 | People in my social circle believe having a job is important for me | ||

| SN4 | The significant people in my life would prefer me to have a job | ||

| Attitude | AT1 | For me, having a job I like is very beneficial | Fenitra et al. [78]; Hoeksma et al. [79] |

| AT2 | For me, having a job I like is very meaningful | ||

| AT3 | For me, having a job I like is very favorable | ||

| AT4 | For me, having a job I like is very desirable | ||

| Intention to Career Shift | ICS1 | I intend to have a career shift to experience job satisfaction in a role I genuinely enjoy | Fenitra et al. [78]; Ghazali et al. [32] |

| ICS2 | I intend to have a career shift to pursue a job that ignites my passion | ||

| ICS3 | I intend to have a career shift to enhance my financial situation | ||

| ICS4 | I intend to have a career shift to prioritize and achieve a better work–life balance | ||

| Organizational Commitment | OC1 | I feel challenged in my current/previous job | Fenitra et al. [78]; Hoeksma et al. [79] |

| OC2 | I am satisfied with my current/previous job | ||

| OC3 | There are opportunities for growth in my current/previous job | ||

| OC4 | The workplace/environment is beneficial for me | ||

| Intention for Greener Pasture | IGP1 | I intend to have a change in career for higher salary | Fenitra et al. [78]; Ghazali et al. [32] |

| IGP2 | I intend to have a change in career for greater opportunities | ||

| IGP3 | I intend to have a change in career for new challenges | ||

| IGP4 | I intend to have a change in career for a new and improved workplace |

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST1 | Between Groups | 41.388 | 4 | 10.347 | 13.115 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 104.931 | 133 | 0.789 | |||

| Total | 146.319 | 137 | ||||

| ST2 | Between Groups | 43.145 | 4 | 10.786 | 27.970 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 51.289 | 133 | 0.386 | |||

| Total | 94.435 | 137 | ||||

| ST3 | Between Groups | 40.111 | 4 | 10.028 | 33.099 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 40.295 | 133 | 0.303 | |||

| Total | 80.406 | 137 | ||||

| ST4 | Between Groups | 22.897 | 4 | 5.724 | 13.586 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 56.038 | 133 | 0.421 | |||

| Total | 78.935 | 137 | ||||

| AR1 | Between Groups | 28.174 | 4 | 7.043 | 23.234 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 40.319 | 133 | 0.303 | |||

| Total | 68.493 | 137 | ||||

| AR2 | Between Groups | 20.904 | 4 | 5.226 | 13.184 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 52.720 | 133 | 0.396 | |||

| Total | 73.623 | 137 | ||||

| AR3 | Between Groups | 10.903 | 4 | 2.726 | 5.214 | 0.001 |

| Within Groups | 69.531 | 133 | 0.523 | |||

| Total | 80.435 | 137 | ||||

| AR4 | Between Groups | 25.247 | 4 | 6.312 | 15.817 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 53.072 | 133 | 0.399 | |||

| Total | 78.319 | 137 | ||||

| PN1 | Between Groups | 34.315 | 4 | 8.579 | 21.001 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 54.330 | 133 | 0.408 | |||

| Total | 88.645 | 137 | ||||

| PN2 | Between Groups | 25.902 | 4 | 6.476 | 14.678 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 58.677 | 133 | 0.441 | |||

| Total | 84.580 | 137 | ||||

| PN3 | Between Groups | 45.132 | 4 | 11.283 | 27.583 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 54.405 | 133 | 0.409 | |||

| Total | 99.536 | 137 | ||||

| PN4 | Between Groups | 38.727 | 4 | 9.682 | 18.620 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 69.157 | 133 | 0.520 | |||

| Total | 107.884 | 137 | ||||

| PN5 | Between Groups | 62.988 | 4 | 15.747 | 33.682 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 62.179 | 133 | 0.468 | |||

| Total | 125.167 | 137 | ||||

| PBC1 | Between Groups | 42.669 | 4 | 10.667 | 26.285 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 53.976 | 133 | 0.406 | |||

| Total | 96.645 | 137 | ||||

| PBC2 | Between Groups | 37.959 | 4 | 9.490 | 21.278 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 59.316 | 133 | 0.446 | |||

| Total | 97.275 | 137 | ||||

| PBC3 | Between Groups | 33.215 | 4 | 8.304 | 20.761 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 53.198 | 133 | 0.400 | |||

| Total | 86.413 | 137 | ||||

| PBC4 | Between Groups | 39.625 | 4 | 9.906 | 19.954 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 66.027 | 133 | 0.496 | |||

| Total | 105.652 | 137 | ||||

| SN1 | Between Groups | 18.602 | 4 | 4.651 | 7.932 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 77.978 | 133 | 0.586 | |||

| Total | 96.580 | 137 | ||||

| SN2 | Between Groups | 9.876 | 4 | 2.469 | 2.743 | 0.031 |

| Within Groups | 119.726 | 133 | 0.900 | |||

| Total | 129.601 | 137 | ||||

| SN3 | Between Groups | 29.207 | 4 | 7.302 | 13.475 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 72.068 | 133 | 0.542 | |||

| Total | 101.275 | 137 | ||||

| SN4 | Between Groups | 28.227 | 4 | 7.057 | 14.429 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 65.048 | 133 | 0.489 | |||

| Total | 93.275 | 137 | ||||

| AT1 | Between Groups | 56.207 | 4 | 14.052 | 59.807 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 31.249 | 133 | 0.235 | |||

| Total | 87.457 | 137 | ||||

| AT2 | Between Groups | 53.241 | 4 | 13.310 | 58.268 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 30.382 | 133 | 0.228 | |||

| Total | 83.623 | 137 | ||||

| AT3 | Between Groups | 52.496 | 4 | 13.124 | 53.249 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 32.780 | 133 | 0.246 | |||

| Total | 85.275 | 137 | ||||

| AT4 | Between Groups | 50.496 | 4 | 12.624 | 37.224 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 45.105 | 133 | 0.339 | |||

| Total | 95.601 | 137 | ||||

| ICS1 | Between Groups | 43.919 | 4 | 10.980 | 29.705 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 49.161 | 133 | 0.370 | |||

| Total | 93.080 | 137 | ||||

| ICS2 | Between Groups | 42.883 | 4 | 10.721 | 28.691 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 49.697 | 133 | 0.374 | |||

| Total | 92.580 | 137 | ||||

| ICS3 | Between Groups | 19.674 | 4 | 4.919 | 5.506 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 118.818 | 133 | 0.893 | |||

| Total | 138.493 | 137 | ||||

| ICS4 | Between Groups | 39.162 | 4 | 9.790 | 19.728 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 66.005 | 133 | 0.496 | |||

| Total | 105.167 | 137 | ||||

| OC1 | Between Groups | 78.989 | 4 | 19.747 | 31.330 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 83.830 | 133 | 0.630 | |||

| Total | 162.819 | 137 | ||||

| OC2 | Between Groups | 47.419 | 4 | 11.855 | 18.724 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 84.204 | 133 | 0.633 | |||

| Total | 131.623 | 137 | ||||

| OC3 | Between Groups | 74.077 | 4 | 18.519 | 42.689 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 57.698 | 133 | 0.434 | |||

| Total | 131.775 | 137 | ||||

| OC4 | Between Groups | 55.978 | 4 | 13.995 | 23.713 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 78.493 | 133 | 0.590 | |||

| Total | 134.471 | 137 | ||||

| IGP1 | Between Groups | 41.559 | 4 | 10.390 | 18.467 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 74.825 | 133 | 0.563 | |||

| Total | 116.384 | 137 | ||||

| IGP2 | Between Groups | 55.017 | 4 | 13.754 | 33.270 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 54.983 | 133 | 0.413 | |||

| Total | 110.000 | 137 | ||||

| IGP3 | Between Groups | 54.368 | 4 | 13.592 | 33.449 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 54.045 | 133 | 0.406 | |||

| Total | 108.413 | 137 | ||||

| IGP4 | Between Groups | 43.582 | 4 | 10.895 | 16.207 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 89.411 | 133 | 0.672 | |||

| Total | 132.993 | 137 | ||||

| Variable | Code | Mean | StDev | Importance | Initial FL | Final FL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Transcendence | ST1 | 4.203 | 1.030 | 73.6% | 0.698 | - |

| ST2 | 4.478 | 0.827 | 78.0% | 0.900 | 0.909 | |

| ST3 | 4.377 | 0.763 | 62.1% | 0.932 | 0.934 | |

| ST4 | 3.978 | 0.756 | 70.7% | 0.803 | 0.835 | |

| Ascription of Responsibility | AR1 | 4.159 | 0.705 | 86.1% | 0.827 | 0.859 |

| AR2 | 3.754 | 0.730 | 100.0% | 0.790 | 0.758 | |

| AR3 | 3.522 | 0.763 | 79.3% | 0.668 | - | |

| AR4 | 3.797 | 0.753 | 76.2% | 0.748 | 0.771 | |

| Personal Norms | PN1 | 4.051 | 0.801 | 80.5% | 0.795 | 0.793 |

| PN2 | 4.101 | 0.783 | 65.5% | 0.793 | 0.792 | |

| PN3 | 4.058 | 0.849 | 73.3% | 0.924 | 0.924 | |

| PN4 | 3.971 | 0.884 | 80.9% | 0.839 | 0.839 | |

| PN5 | 4.167 | 0.952 | 81.0% | 0.850 | 0.851 | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC1 | 3.949 | 0.837 | 83.3% | 0.898 | 0.898 |

| PBC2 | 3.928 | 0.840 | 93.3% | 0.889 | 0.890 | |

| PBC3 | 4.065 | 0.791 | 81.3% | 0.876 | 0.875 | |

| PBC4 | 4.130 | 0.875 | 64.9% | 0.857 | 0.856 | |

| Subjective Norm | SN1 | 3.768 | 0.837 | 78.0% | 0.598 | - |

| SN2 | 3.312 | 0.969 | 79.5% | 0.547 | - | |

| SN3 | 3.928 | 0.857 | 80.0% | 0.894 | 0.960 | |

| SN4 | 3.928 | 0.822 | 73.8% | 0.916 | 0.967 | |

| Attitude | AT1 | 4.413 | 0.796 | 84.1% | 0.972 | 0.972 |

| AT2 | 4.420 | 0.778 | 81.2% | 0.968 | 0.968 | |

| AT3 | 4.406 | 0.786 | 87.7% | 0.982 | 0.982 | |

| AT4 | 4.355 | 0.832 | 95.0% | 0.947 | 0.947 | |

| Intention to Career Shift | ICS1 | 4.268 | 0.821 | 81.4% | 0.924 | 0.936 |

| ICS2 | 4.232 | 0.819 | 87.2% | 0.945 | 0.950 | |

| ICS3 | 3.493 | 1.002 | 78.5% | 0.501 | - | |

| ICS4 | 4.167 | 0.873 | 86.3% | 0.837 | 0.831 | |

| Organizational Commitment | OC1 | 3.297 | 1.086 | 89.0% | 0.814 | 0.814 |

| OC2 | 3.420 | 0.977 | 82.9% | 0.892 | 0.892 | |

| OC3 | 3.572 | 0.977 | 80.5% | 0.911 | 0.911 | |

| OC4 | 3.514 | 0.987 | 99.4% | 0.859 | 0.859 | |

| Intention for Greener Pasture | IGP1 | 3.862 | 0.918 | 100.0% | 0.844 | 0.844 |

| IGP2 | 4.000 | 0.893 | 98.9% | 0.945 | 0.945 | |

| IGP3 | 4.065 | 0.886 | 76.4% | 0.915 | 0.915 | |

| IGP4 | 3.659 | 0.982 | 86.3% | 0.829 | 0.829 |

| Variable | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 0.977 | 0.983 | 0.935 |

| Ascription of Responsibility | 0.718 | 0.839 | 0.636 |

| Intention to Career Shift | 0.892 | 0.933 | 0.823 |

| Intention for Greener Pasture | 0.906 | 0.935 | 0.782 |

| Organizational Commitment | 0.893 | 0.926 | 0.757 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.903 | 0.932 | 0.774 |

| Personal Norms | 0.897 | 0.924 | 0.708 |

| Subjective Norms | 0.923 | 0.963 | 0.928 |

| Self-Transcendence | 0.874 | 0.922 | 0.799 |

| Fornell-Larcker Criterion | |||||||||

| Variable | AT | AR | ICS | IGP | OC | PBC | PN | SN | ST |

| AT | 0.967 | ||||||||

| AR | 0.594 | 0.797 | |||||||

| ICS | 0.745 | 0.530 | 0.907 | ||||||

| IGP | 0.447 | 0.448 | 0.505 | 0.885 | |||||

| OC | 0.406 | 0.684 | 0.455 | 0.506 | 0.870 | ||||

| PBC | 0.543 | 0.563 | 0.537 | 0.419 | 0.404 | 0.880 | |||

| PN | 0.619 | 0.648 | 0.512 | 0.415 | 0.423 | 0.623 | 0.841 | ||

| SN | 0.506 | 0.481 | 0.535 | 0.552 | 0.634 | 0.419 | 0.622 | 0.963 | |

| ST | 0.652 | 0.604 | 0.613 | 0.423 | 0.504 | 0.490 | 0.554 | 0.372 | 0.894 |

| Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio | |||||||||

| Variable | AT | AR | ICS | IGP | OC | PBC | PN | SN | ST |

| AT | |||||||||

| AR | 0.693 | ||||||||

| ICS | 0.794 | 0.649 | |||||||

| IGP | 0.470 | 0.546 | 0.564 | ||||||

| OC | 0.579 | 0.404 | 0.599 | 0.337 | |||||

| PBC | 0.579 | 0.685 | 0.594 | 0.461 | 0.529 | ||||

| PN | 0.652 | 0.785 | 0.565 | 0.448 | 0.673 | 0.676 | |||

| SN | 0.531 | 0.573 | 0.591 | 0.385 | 0.563 | 0.457 | 0.685 | ||

| ST | 0.695 | 0.736 | 0.687 | 0.473 | 0.639 | 0.548 | 0.611 | 0.541 | 0.000 |

References

- Andersson, M.-L. The meaning of work and Job. Int. J. Value-Based Manag. 1992, 5, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, N.C.; Weiss, R.S. The function and meaning of work and the job. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1955, 20, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Most in-Demand Jobs in the Philippines. 2024. Available online: https://digido.ph/articles/in-demand-jobs-philippines (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Gumasing, M.J.J.; Rendon, E.R.; German, J.D. Sustainable ergonomic workplace: Fostering job satisfaction and productivity among business process outsourcing (BPO) workers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Lutz, S.U. The Health Knowledge Mechanism: Evidence on the link between education and Health Lifestyle in the Philippines. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2018, 20, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, K.; Bjørnnes, A.K.; Lohne, V.; Nortvedt, L. Motivation, education, and expectations: Experiences of philippine immigrant nurses. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 215824402110165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.P. The function and meaning of work and the job: Morse and Weiss (1955) revisited. Acad. Manag. J. 1980, 23, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Population. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/population#:~:text=Our%20growing%20population&text=The%20world’s%20population%20is%20expected,billion%20in%20the%20mid%2D2080s (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Clark, D. Global Employment Rate by Region. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1258882/global-employment-rate-by-region/ (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Balita, C. Philippines: Number of Jobseekers. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1337516/philippines-number-of-jobseekers/ (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Armstrong, M. Infographic: World Population Reaches 8 Billion. Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/28744/world-population-growth-timeline-and-forecast/ (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Lo, K. Latest Labor Force Survey Results Reflect Continued Improvement of PH Jobs Market and Quality of Jobs for Filipinos. Available online: https://www.dof.gov.ph/latest-labor-force-survey-results-reflect-continued-improvement-of-ph-jobs-market-and-quality-of-jobs-for-filipinos/ (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Philippine Statistics Authority Labor Turnover Statistics|Philippine Statistics Authority|Republic of the Philippines. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/labor-turnover-survey (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Ong, A.K. A machine learning ensemble approach for predicting factors affecting STEM students’ future intention to enroll in chemistry-related courses. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meniado, J.C. Second language acquisition: The case of Filipino migrant workers. Adv. Lang. Lit. Stud. 2019, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, A.; Tiongson, E.R. Philippine Migration Journey: Processes and Programs in the Migration life Cycle. 2023. Available online: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/10c897a0730557682d8b1d67a5a65adc-0050062023/original/Philippine-Migration-Experience-and-Cases-FORMATTED.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Ibarra, H. Career Transition and Change. INSEAD. 2004. Available online: https://flora.insead.edu/fichiersti_wp/inseadwp2004/2004-97.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Nicholson, N. A theory of work role transitions. Adm. Sci. Q. 1984, 29, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latack, J.C. Career transitions within organizations: An exploratory study of work, nonwork, and Coping Strategies. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1984, 34, 296–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NLS FAQS. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/nls/questions-and-answers.htm#anch43 (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Pak, K.; Kooij, D.T.A.M.; De Lange, A.H.; Van Veldhoven, M.J.P.M. Human Resource Management and the ability, motivation and opportunity to continue working: A Review of Quantitative Studies. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 29, 336–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garthe, N.; Hasselhorn, H.M. Changes of profession, employer and work tasks in later working life: An empirical overview of staying and leaving. Ageing Soc. 2021, 42, 2393–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhenjing, G.; Chupradit, S.; Ku, K.Y.; Nassani, A.A.; Haffar, M. Impact of employees’ workplace environment on employees’ performance: A multi-mediation model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 890400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, R.C.; Abad-Pinlac, B.; Yao, D.P.; Toribio, F.N.; Josephsson, S.; Sy, M.P. Unraveling the “greener pastures” concept: The phenomenology of internationally educated occupational therapists. OTJR Occup. Ther. J. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inocian, R.; de los Reyes, C.E.; Lasala, G.; Pacaña, G.; Dawa, D. Changing Mobility of Filipino Professionals in Response to K to 12 Implementation in the Philippines. Eur. Sci. J. 2015, 11, 36–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feakes, A.M.; Palmer, E.J.; Petrovski, K.R.; Thomsen, D.A.; Hyams, J.H.; Cake, M.A.; Webster, B.; Barber, S.R. Predicting career sector intent and the theory of planned behaviour: Survey findings from Australian Veterinary Science Students. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Peng, K.Z.; Wu, C. Career proactivity: A bibliometric literature review and a future research agenda. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 72, 144–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgievski, M.J.; Stephan, U.; Laguna, M.; Moriano, J.A. Predicting entrepreneurial career intentions. J. Career Assess. 2017, 26, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maljugić, B.; Ćoćkalo, D.; Bakator, M.; Stanisavljev, S. The role of the Quality Management Process within Society 5.0. Societies 2024, 14, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino, A.; Moreira, A.; Cesário, F.; Pinto-Coelho, M. Adaptation of the work-related quality of life-2 scale (WRQOL-2) among Portuguese workers. Societies 2024, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.M.; Nguyen, B.; Mutum, D.S.; Yap, S.-F. Pro-Environmental behaviours and value-belief-norm theory: Assessing unobserved heterogeneity of two ethnic groups. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Hayat, N.; Mohiuddin, M.; Salameh, A.A.; Ali, M.H.; Zainol, N.R. Modelling the significance of value-belief-norm theory in predicting workplace energy conservation behaviour. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 940595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homocianu, D. Life satisfaction: Insights from the World Values Survey. Societies 2024, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.; Mónico, L.; Pinto, A.; Oliveira, S.; Leite, E. Effects of work–family conflict and facilitation profiles on work engagement. Societies 2024, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udo, G.; Bagchi, K. The role of personal norm in predicting intention for digital piracy. Issues Inf. Syst. 2019, 20, 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Dhali, K.; Al Masud, A.; Hossain, M.A.; Lipy, N.S.; Chaity, N.S. The effects of abusive supervision on the behaviors of employees in an organization. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 8, 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, R.; Hossain, M.A.; Al Masud, A. Job stress and organizational citizenship behavior among university teachers within Bangladesh: Mediating influence of occupational commitment. Management 2020, 24, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, M.; Håkansson, E. Work Life Balance—A Question of Income and Gender? Available online: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1216561/FULLTEXT02.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Yao, K.; Franco, E.P.; Hechanova, M.R. Rewards that Matter: What Motivates the Filipino Employee. Available online: https://archium.ateneo.edu/psychology-faculty-pubs/202/ (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Wong, P.T.; Page, D.; Cheung, T.C. A self-transcendence model of servant leadership. In The Palgrave Handbook of Servant Leadership; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Morillo, H.M.; Capuno, J.J.; Mendoza, A.M. Views and values on family among Filipinos: An empirical exploration. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 41, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, T.Y.; Noh, S.; Lee, J.; Takeuchi, D. Culture and family process: Measures of familism for Filipino and Korean American parents. Fam. Process 2017, 57, 1029–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, Y.; Nicole Bandoquillo, X.; Marie Hernandez, S.; Zyrene Monge, R.; Francis Dominique Tomas, K. Factors affecting perceived work performance among work- from-home filipino workforce: An integration of the job demands-resources theory. Soc. Occup. Ergon. 2022, 65, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Fauzi, M.A.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Kunjuraman, V. Tourists’ intention to visit Green Hotels: Building on the theory of planned behaviour and the value-belief-norm theory. J. Tour. Futures 2022, 10, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenitra, R.M.; Premananto, G.C.; Sedera, R.M.; Abbas, A.; Laila, N. Environmentally responsible behavior and knowledge-belief-norm in the tourism context: The moderating role of types of destinations. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2022, 10, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfman, N.; Cisternas, P.; López-Vázquez, E.; Maza, C.; Oyanedel, J. Understanding attitudes and pro-environmental behaviors in a Chilean community. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14133–14152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bengtsson, M. Cause I’ll feel good! an investigation into the effects of anticipated emotions and personal moral norms on consumer pro-environmental behavior. J. Promot. Manag. 2017, 23, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocirlan, C.E.; Gregory-Smith, D.; Manika, D.; Wells, V. Using values, beliefs, and norms to predict conserving behaviors in organizations. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2020, 17, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A. Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Fostering customers’ pro-environmental behavior at a museum. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 1240–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilagan, J.R.A.; Hechanova, M.R.M.; Co, T.A.C.; Pleyto, V.J.Z. “Bakit Ka Kumakayod?” Developing a Filipino Needs Theory of Motivation. Philipp. J. Psychol. 2014, 47, 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Irabor, I.E.; Okolie, U.C. A review of employees’ job satisfaction and its affect on their retention. Ann. Spiru Haret Univ. Econ. Ser. 2019, 19, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumasing, M.J.J.; Ilo, C.K. The impact of job satisfaction on creating a sustainable workplace: An empirical analysis of organizational commitment and lifestyle behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing: A Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. 2006. Available online: http://people.umass.edu/~aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Zhang, Y.; Moyle, B.D.; Jin, X. Fostering visitors’ pro-environmental behaviour in an urban park. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Valera, M.M.; Meseguer de Pedro, M.; De Cuyper, N.; García-Izquierdo, M.; Soler Sanchez, M.I. Explaining job search behavior in unemployed youngsters beyond perceived employability: The role of Psychological Capital. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooft, E.V. Motivation and self-regulation in job search: A theory of planned job search behavior. In The Oxford Handbook of Job Loss and Job Search; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fisbbein, M. Factors influencing intentions and the intention-behavior relation. Hum. Relat. 1974, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A.; Ling Tan, C.N.; Thurasamy, R.; Ojo, A.O. Evaluating academics’ knowledge sharing intentions in Malaysian public universities. Malays. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2019, 24, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, A.; Demerouti, E.; Ceschi, A.; Sartori, R. Implementing job crafting behaviors: Exploring the effects of a job crafting intervention based on the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2020, 58, 477–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.J.; Garabiles, M.R.; Latkin, C.A. Work life, relationship, and policy determinants of health and well-being among Filipino domestic workers in China: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreg, S.; Katz-Gerro, T. Predicting proenvironmental behavior cross-nationally. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 462–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, P.; Timms, C.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Kalliath, T.; Siu, O.-L.; Sit, C.; Lo, D. Work–life balance: A longitudinal evaluation of a new measure across Australia and New Zealand workers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 2724–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, S.J. Cultural revitalisation. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2008, 3, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Montenegro, L.D.; Nadlifatin, R.; Kurata, Y.B.; Ong, A.K.; Chuenyindee, T. The influence of organizational commitment on the perceived effectiveness of virtual meetings by Filipino professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A structural equation modeling approach. Work 2022, 71, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.Y.; Lee, M.K.; Fairchild, E.M.; Caubet, S.L.; Peters, D.E.; Beliles, G.R.; Matti, L.K. Relationships among organizational values, employee engagement, and patient satisfaction in an Academic Medical Center. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2020, 4, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumban, E. Nearly a Third of PHL Workforce Expecting to Switch Jobs over Next 12 Months—Study. Available online: https://www.bworldonline.com/economy/2023/08/03/537771/nearly-a-third-of-phl-workforce-expecting-to-switch-jobs-over-next-12-months-study/ (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Mohanasundari, S.K.; Sonia, M. The relationship between components of sample size estimate and sample size. Asian J. Nurs. Educ. Res. 2022, 12, 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Carfora, V.; Buscicchio, G.; Catellani, P. Integrating personal and pro-environmental motives to explain Italian women’s purchase of Sustainable Clothing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highlights of the January 2024 Labor Force Survey. Labor Force Survey|Philippine Statistics Authority|Republic of the Philippines. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/labor-force-survey (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- AbouAssi, K.; McGinnis Johnson, J.; Holt, S.B. Job mobility among millennials: Do they stay or do they go? Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2019, 41, 219–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumasing, M.J.J.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Ong, A.K.; Nadlifatin, R. Determination of factors affecting the response efficacy of Filipinos under Typhoon Conson 2021 (jolina): An extended protection motivation theory approach. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 70, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenitra, R.M.; Laila, N.; Premananto, G.C.; Abbas, A.; Sedera, R.M. Explaining littering prevention among park visitors using the theory of planned behavior and Norm Activation Model. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2023, 11, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeksma, D.L.; Gerritzen, M.A.; Lokhorst, A.M.; Poortvliet, P.M. An extended theory of planned behavior to predict consumers’ willingness to buy Mobile Slaughter Unit Meat. Meat Sci. 2017, 128, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kiraz, A.; Canpolat, O.; Özkurt, C.; Taşkın, H. Analysis of the factors affecting the industry 4.0 tendency with the structural equation model and an application. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 150, 106911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampofo, R.T.; Aidoo, E.N. Structural equation modelling of COVID-19 knowledge and attitude as determinants of preventive practices among university students in Ghana. Sci. Afr. 2022, 16, e01182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, Q.N.; Alam, M.M.; Tairan, N. Structural equation modeling for mobile learning acceptance by university students: An empirical study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in Social Sciences and Technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasawa, I.; Tanioka, K.; Yadohisa, H. Clustered sparse structural equation modeling for heterogeneous data. J. Classif. 2023, 40, 588–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, J.D.; Ong, A.K.; Redi, A.A.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Robas, K.P.; Nadlifatin, R.; Chuenyindee, T. Classification modeling of intention to donate for victims of Typhoon odette using Deep Learning Neural Network. Environ. Dev. 2023, 45, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. Using SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 4th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Response to Leslie Hayduk’s review of Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 4th edition. Can. Stud. Popul. 2018, 45, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural Equation Modeling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, H.; Homburg, C. Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and Consumer Research: A Review. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B.; Arthur, M.B. An exploratory study of perceived career change and job attitudes among job changers. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 19, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, Z.; Oon, S.W.; Fikry, A. Consumer attitude: Does it influencing the intention to use mhealth? Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 105, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, L.M.; Judge, T.A. Employee attitudes and job satisfaction. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmen, K.P.H.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Veldhuizen, I.J.T.; Schaalma, H.P. Psychosocial correlates of personal norms. In Psychology of Motivation; Brown, L.V., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan, B.; Afiff, A.Z.; Heruwasto, I. Personal norm and pro-environmental consumer behavior: An application of Norm Activation theory. ASEAN Mark. J. 2021, 13, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolderdijk, J.W.; Steg, L.; Geller, E.S.; Lehman, P.K.; Postmes, T. Comparing the effectiveness of monetary versus moral motives in environmental campaigning. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 3, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, R.; Devine-Wright, P.; Mill, G.A. Interactions between perceived behavioral control and personal-normative motives. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2008, 2, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhai, J. Understanding Waste Management Behavior among university students in China: Environmental knowledge, personal norms, and the theory of planned behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 771723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akitsu, Y.; Ishihara, K.N. An integrated model approach: Exploring the energy literacy and values of lower Secondary students in Japan. Int. J. Educ. Methodol. 2018, 4, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.E.; Tirotto, F.A.; Pagliaro, S.; Fornara, F. Two sides of the same coin: Environmental and health concern pathways toward meat consumption. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 578582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, F.K.; Kaplowitz, M. Explaining energy conservation and environmental citizenship behaviors using the value-belief-norm framework. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2016, 22, 137–159. [Google Scholar]

- Fornara, F.; Pattitoni, P.; Mura, M.; Strazzera, E. Predicting intention to improve household energy efficiency: The role of value-belief-norm theory, normative and informational influence, and specific attitude. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Effects of values, problem awareness, and personal norm on willingness to reduce personal car use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin-Fanning, F.; Ricks, J.M. Attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioral control factors influencing participation in a cooking skills program in rural Central Appalachia. Glob. Health Promot. 2016, 24, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, J.; Krzeski, E.; Harden, S.; Cook, E.; Allen, K.; Estabrooks, P.A. Qualitative application of the theory of planned behavior to understand beverage consumption behaviors among adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1774–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, J.; Wetzels, M. A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model: Investigating subjective norm and moderation effects. Inf. Manag. 2007, 44, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Ham, S.; Yang, I.S.; Choi, J.G. The roles of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control in the formation of consumers’ behavioral intentions to read menu labels in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. Assessing the moderating effect of subjective norm on luxury purchase intention: A study of gen Y consumers in India. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Attitudes, intentions, and behavior: A test of some key hypotheses. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 41, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1992, 55, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, T.; Parreira, P.; Rodrigues, V.; Graveto, J. Organizational commitment and intention to leave of nurses in Portuguese hospitals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A. The relationship among job characteristics organizational commitment and employee turnover intentions. J. Work-Appl. Manag. 2018, 10, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaff, L.A. The Protestant Ethic. In Max Weber in America; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mudrack, P.E. Protestant work-ethic dimensions and work orientations. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1997, 23, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, R. The Protestant work ethic and attitudes towards work. Sci. Bull. 2018, 23, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J.I.M.; Bondy, K.; Schuitema, G. Listen to others or yourself? the role of personal norms on the effectiveness of social norm interventions to change pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 78, 101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, R.; Larsen, S. The relative importance of social and personal norms in explaining intentions to choose eco-friendly travel options. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 18, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, M.; Jeger, M.; Frajman Ivković, A. The role of subjective norms in forming the intention to purchase Green Food. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2015, 28, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Thøgersen, J.; Ruan, Y.; Huang, G. The moderating role of human values in planned behavior: The case of Chinese consumers’ intention to buy organic food. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. An introduction to structural equation modeling. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. Classroom Companion: Business; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, D.M.; Tarvydas, V.M.; Gladding, S.T. 20/20: A vision for the future of counseling: The new consensus definition of Counseling. J. Couns. Dev. 2014, 92, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, M.G. Strategic Human Resource Management and public employee retention. Rev. Econ. Political Sci. 2018, 3, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.; Aman, N.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Shah, S.H. Perceived corporate social responsibility, ethical leadership, and moral reflectiveness impact on pro-environmental behavior among employees of small and Medium Enterprises: A double-mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 967859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koçak, O.; Ak, N.; Erdem, S.S.; Sinan, M.; Younis, M.Z.; Erdoğan, A. The role of family influence and academic satisfaction on career decision-making self-efficacy and happiness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedge, J.; Rineer, J.R. Improving Career Development Opportunities through Rigorous Career Pathways Research; RTI Press: Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wenz, A.; Al Baghal, T.; Gaia, A. Language proficiency among respondents: Implications for data quality in a longitudinal face-to-face survey. J. Surv. Stat. Methodol. 2020, 9, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kelly, G.; Janssen, M.; Rana, N.P.; Slade, E.L.; Clement, M. Social Media: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mohamed, A.A.; Al Mohamed, S.; Zino, M. Application of fuzzy multicriteria decision-making model in selecting pandemic hospital site. Future Bus. J. 2023, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Mohamed, S.A.; Ahmad, M. Solving aggregate production planning problem with uncertainty using fuzzy goal programming. Int. J. Math. Oper. Res. 2022, 25, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeblak, A.; Al Mohamed, A. Use of fuzzy time series to predict the numbers of students enrolled in the Private University of Ebla (case study at the Faculty of Engineering in Aleppo). J. Sci. Comput. Eng. Res. (JSCER) 2021, 2, 184–189. [Google Scholar]

| Item | Type | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Under 25 years old | 12 | 5.700 |

| 25–34 years old | 109 | 51.90 | |

| 35–44 years old | 55 | 26.20 | |

| 45 years old and above | 34 | 16.20 | |

| Gender | Male | 120 | 57.14 |

| Female | 90 | 42.86 | |

| Highest Educational Attainment | Doctorate Degree | 12 | 5.710 |

| Master’s Degree | 71 | 33.81 | |

| Undergraduate | 107 | 50.95 | |

| Vocational Course | 10 | 4.760 | |

| High school Graduate | 9 | 4.290 | |

| Elementary Graduate | 1 | 0.480 | |

| Are you currently employed? | Yes | 205 | 97.62 |

| No | 5 | 2.380 | |

| Previous/current job | BPO, IT, and Business Services | 42 | 20.00 |

| Construction Industry | 8 | 3.810 | |

| E-Commerce Industry | 2 | 0.950 | |

| Food industry | 25 | 11.90 | |

| Manufacturing Industry | 2 | 0.950 | |

| Government agency | 51 | 24.29 | |

| Real Estate Industry | 8 | 3.810 | |

| Retail Industry | 3 | 1.430 | |

| Telecom Industry | 67 | 31.91 | |

| Tourism Industry | 2 | 0.950 | |

| Status of previous/current job | Regular | 26 | 12.38 |

| Part-time | 1 | 0.480 | |

| Contractual | 183 | 87.14 | |

| Monthly income (in PHP) | Less than 15,000 | 39 | 18.57 |

| 15,000–30,000 | 77 | 36.67 | |

| 30,000–45,000 | 44 | 20.95 | |

| 45,000–60,000 | 19 | 9.048 | |

| 60,000–75,000 | 14 | 6.667 | |

| More than 75,000 | 7 | 8.095 | |

| Years of job experience | 1–3 | 42 | 20.00 |

| 4–6 | 59 | 28.10 | |

| 7–9 | 34 | 16.19 | |

| 10–12 | 20 | 9.520 | |

| 12–15 | 19 | 9.050 | |

| 16 and above | 36 | 17.14 | |

| How satisfied are you with your current/previous job? | 1—Not at all satisfied | 5 | 2.380 |

| 2—Slightly satisfied | 21 | 10.00 | |

| 3—Moderately satisfied | 74 | 35.24 | |

| 4—Very satisfied | 78 | 37.14 | |

| 5—Completely satisfied | 32 | 15.24 |

| Hypotheses | Relationship | Β-Values | p-Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ST→AR | 0.604 | <0.001 | Accept |

| 2 | ST→PN | 0.255 | 0.001 | Accept |

| 3 | AR→PN | 0.494 | <0.001 | Accept |

| 4 | PN→PBC | 0.623 | <0.001 | Accept |

| 5 | PBC→IGP | 0.301 | <0.001 | Accept |

| 6 | PBC→ICS | 0.187 | <0.001 | Accept |

| 7 | AT→IGP | 0.282 | <0.001 | Accept |

| 8 | AT→ICS | 0.644 | <0.001 | Accept |

| 9 | SN→AT | 0.506 | <0.001 | Accept |

| 10 | OC→IGP | −0.338 | <0.001 | Accept |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belida, P.R.C.; Ong, A.K.S.; Young, M.N.; German, J.D. Determining the Factors Influencing the Behavioral Intention of Job-Seeking Filipinos to Career Shift and Greener Pasture. Societies 2024, 14, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14080145

Belida PRC, Ong AKS, Young MN, German JD. Determining the Factors Influencing the Behavioral Intention of Job-Seeking Filipinos to Career Shift and Greener Pasture. Societies. 2024; 14(8):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14080145

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelida, Prince Reuben C., Ardvin Kester S. Ong, Michael N. Young, and Josephine D. German. 2024. "Determining the Factors Influencing the Behavioral Intention of Job-Seeking Filipinos to Career Shift and Greener Pasture" Societies 14, no. 8: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14080145

APA StyleBelida, P. R. C., Ong, A. K. S., Young, M. N., & German, J. D. (2024). Determining the Factors Influencing the Behavioral Intention of Job-Seeking Filipinos to Career Shift and Greener Pasture. Societies, 14(8), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14080145