1. Introduction

Since 2012, twenty-four states have legalized adult-use recreational cannabis. To varying degrees, state laws allow for the production, distribution, retail sale, and on-site consumption of cannabis in licensed businesses [

1].

1 In addition, recreational cannabis is decriminalized in the District of Columbia and the territory of Guam. Although legislative provisions vary across these jurisdictions, they have the combined effect of decriminalizing recreational cannabis for 54% of the U.S. population. A recent trend in cannabis decriminalization is that states have placed greater emphasis on incorporating social equity goals with the legalization of recreational cannabis. Prior to this shift in policy emphasis, cannabis legalization was more focused on curbing law enforcement costs, creating regulatory frameworks for medical uses of cannabis, and developing cannabis markets as a source of new tax revenue [

2]. New York and other states that recently passed legislation to legalize recreational cannabis exemplify the increased focus on cannabis legalization as a tool to promote social and economic equity. A defining feature of New York’s 2021 Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act (MRTA) was its social and economic equity provisions [

3]. The provisions set aside at least half of the state’s recreational cannabis dispensary licenses for members of communities disproportionally impacted by punitive drug laws and provided business assistance to equity applicants. In addition, the Act earmarked revenue for taxes on recreational cannabis for projects and programs that directly benefit black and brown communities disproportionally impacted by the war on drugs.

The growing emphasis on linking social equity goals with the legalization of recreational cannabis should be viewed against the backdrop of the stigmatization of both marijuana in society and the entrepreneurs who are the expected beneficiaries of social equity provisions. Understanding how states have approached the creation and implementation of these types of business set-asides provides insights into the degree to which social and economic equity programs can achieve their goals. This is the case when a nexus exists between a highly stigmatized industry and a group of entrepreneurs, as well as in economic sectors that are more mainstream.

At its core, this article asks if, under their current structure and implementation, recreational cannabis laws achieve social equity goals. More specifically, differentiation in the social equity provisions of state laws governing business set-asides for recreational cannabis dispensaries is examined. The methods for this analysis are two-pronged. First, content analysis of public policy documents is used to examine social equity provisions in state and local cannabis laws applicable to large U.S. cities (2020 population > 600,000). Second, spatial analysis is used to gain insights into how the geography of cannabis businesses furthers or hampers the core social and economic equity goals of the law. The findings from the analysis are used to generate recommendations to strengthen the social and economic equity outcomes from the implementation of recreational cannabis policy nationally.

2. Literature Review

2.1. From Social Stigma to Social Equity?

The social stigma associated with marijuana was engrained in the 1930s when the film

Reefer Madness was released [

3]. Stereotypes about race, criminality, and illicit drug use have framed discussions of marijuana reform historically and contemporaneously [

4,

5,

6]. At the federal level, laws like the 1937 Marijuana Tax Act were passed to restrict the cultivation, possession, and distribution of cannabis in the United States. Restrictions on cannabis production were enhanced when marijuana was listed as a Schedule I drug in the 1970 Controlled Substance Act, identifying it, along with other drugs like heroin and LSD, as a substance with no medical value, a high potential for abuse, and addictive. As a Schedule I drug, marijuana was prioritized by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and other law enforcement agencies and is subject to some of the heaviest criminal penalties connected to federal drug enforcement.

The ubiquitousness of social stigmatization, and the codification of these stigmas in law, reduces public acceptance of cannabis businesses in a legalized and regulated context [

7]. Consequently, cannabis businesses are included in a subset of establishments associated with social dysfunction and vice. After legalization, local land use and zoning ordinances have been applied to cannabis businesses in a similar manner to methadone clinics, homeless shelters, strip clubs, liquor stores, and other unwanted land uses [

8]. Restrictive land use regulations have produced an uneven geography where cannabis businesses end up clustering in economically disenfranchised black and brown communities [

9,

10]. Spatial inequality associated with local land use regulations and the siting of cannabis businesses has been documented in the empirical literature [

4,

7,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Retailer density is an important factor to track since it has been correlated with increased alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use. Marijuana use in low-income, underserved neighborhoods tends to increase with retail density [

7,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Studies have found that proximity to alcohol retail locations correlates with increased alcohol abuse [

21,

22,

23]. Similarly, it has been found that the higher density of tobacco retailers in low-income neighborhoods and the marketing of low-price tobacco products increase the use of tobacco products by youth [

24].

The stigmatization of marijuana has carried over with its legalization. Rather than mainstreaming cannabis businesses, the taboo nature of recreational marijuana has been woven into economic development strategies associated with its legalization. This is most visible when examining strategies for economic development that follow the drug tourism model [

25]. The tolerance of the marijuana economy in Amsterdam exemplifies this centrality of social stigma in the drug tourism model. Under this model, the use and sale of recreational marijuana are confined to limited geographic areas where other vice businesses are found. For example, in Amsterdam, marijuana sales and consumption are confined to the city’s “red light” district where prostitution and other sex tourism businesses cluster. Jamaica provides another example where marijuana’s social stigma is wedded to drug tourism. There, travelers can take ganja tours where they learn about Rastafarian culture while visiting cannabis plantations. Within the framework of drug tourism, cannabis is marketed as a tolerated, off-the-beaten-path, and taboo experience wherein thrill seekers can partake. Even in the United States, where the drug tourism model is not as aggressively pursued, the stigmatization of recreational cannabis still shapes its regulation and land use policies after legalization [

26,

27].

2.2. The Nexus between a Stigmatized Industry and Stigmatized Entrepreneurs

It is important to analyze social equity policies related to recreational cannabis in the context of the stigmatized industry in which they are embedded. Marijuana is a product that carries a social stigma, whether it is sold illicitly or in a regulated and legal framework. This stigma was one of the drivers behind aggressive law enforcement during the war on drugs in black and brown communities. For decades, policies related to the war on drugs led to higher rates of incarceration and longer prison sentences for African Americans and Hispanics [

28,

29]. In response to this outcome, there has been increased advocacy for the adoption of social equity policies to promote restorative justice. One of the social equity provisions tied to recreational cannabis legalization involves vacating sentences of people convicted of marijuana offenses. In addition to these provisions, social equity measures have been put in place to provide prior offenders and members of communities adversely impacted by the war on drugs with opportunities to operate businesses in the cannabis industry. Although these opportunities mirror the framework and intention of traditional set-aside programs for minority-owned and women-owned business enterprises (MWBEs), social equity policies linked to cannabis legalization are hampered by a double stigma associated with the marijuana industry and the entrepreneurs who are prioritized for assistance in policy discourse, formerly incarcerated black and brown men. This nexus between a stigmatized industry and stigmatized entrepreneurs has been a central concern of scholars [

17,

28,

29].

Past research on the use of set-aside programs for MWBEs has identified three core issues that limit their ability to promote business development among the entrepreneurs they target. First, set-aside programs for MWBEs have been criticized for lacking investment in the administrative infrastructure necessary to implement them effectively [

30]. This critique focuses on the lack of precision in determining which weighting factors are used when awarding contracts to MWBEs, the lack of tracking success and failure rates for MWBEs that participate in set-aside programs, and the presence of barriers entrepreneurs face in accessing information and assistance in navigating the application process for set aside programs. Second, set-aside programs for MWBEs have been criticized for having overinclusive and vague eligibility categories [

31]. Expanding the pool of possible applicants for set-asides results in the crowding out of the core population of entrepreneurs targeted for assistance (i.e., African Americans, Hispanics, Asian Americans, and Native Americans). Finally, set-aside programs have been criticized for skewing the selection of entrepreneurs who receive contracts toward larger and better-resourced firms [

32,

33]. This has the effect of stifling the impact of MWBE programs to assist new start-up businesses and reducing the impact that set-aside programs have on small businesses.

The general critiques of set-aside programs for MWBEs are elevated in the context of social equity policies linked to cannabis legalization. This is because black and brown entrepreneurs face added obstacles due to the double stigma associated with the marijuana industry and the prioritization of ex-offenders and members of communities adversely impacted by the war on drugs for assistance. These characteristics of social equity policies linked to cannabis legalization make this analysis a critical case study. This analysis will provide insights into how states have designed social equity policies, and the degree to which they reproduce obstacles to successful set-aside programs for MWBEs. The findings from the analysis are used to generate recommendations to strengthen the social and economic equity outcomes from the implementation of recreational cannabis policy nationally and to inform other set-aside programs for MWBE programs.

3. Methodology

This article examines the structure and implementation of social equity provisions in recreational cannabis laws. The analysis was national in scope, examining the provisions for social equity in large U.S. cities in states where recreational cannabis is legal. The methods for this analysis were two-pronged. First, content analysis of public policy documents was used to examine social equity provisions in state and local cannabis laws applicable to large U.S. cities (2020 population > 600,000). Second, spatial analysis of a subset of cities was used to gain insights into how the geography of cannabis businesses furthers or hampers the core social and economic equity goals of local laws.

For the first part of the analysis, large U.S. cities (2020 population > 600,000) were identified in the twenty-four states that had legalized recreational cannabis use between 2012 and 2023. This cutoff point was selected to limit the analysis to larger core cities where a critical mass of businesses could be identified and where local governments were most likely to have the capacity to share data on cannabis policy. These two criteria were used to ensure that enough recreational cannabis dispensaries were available to analyze in a defined urban geography and that local governments had the capacity to document their licensing practices and share data in digital formats needed for the analysis. Our methodology was also informed by prior research [

4] indicating that although social equity policies are adopted at the state level, decisions about their implementation are delegated to local government. State laws allow local jurisdictions to opt out of licensing recreational cannabis dispensaries, and many smaller jurisdictions exercise this option or only approve a small number of licenses, leaving larger population centers as the primary locations where this type of business clusters.

After applying the selection criteria, a total of twelve cities were identified in ten states that met the criteria to be included in the analysis. Data were collected for these cities by retrieving information from municipal websites, reviewing state and local enabling legislation, and through direct contact with staff in municipal departments and state agencies responsible for implementing the licensing process for recreational cannabis dispensaries. These data were used to categorize the cities based on three dimensions: (1) the social equity framework used for recreational cannabis businesses, (2) the criteria used to identify social equity entrepreneurs, and (3) the benefits available to social equity entrepreneurs.

In the second part of the analysis equity and non-equity businesses were mapped for a subset of cities (N = 3) using census county division (CCD) boundaries to gain insights into how the geography of cannabis businesses furthers or hampers the core social and economic equity goals of laws. The subset of cities was selected based on the availability of data identifying businesses by their street address and social equity status. These maps identify the location of equity and non-equity recreation cannabis dispensaries. The locations of the businesses were overlayed on maps showing the 2021 area deprivation index (ADI). The ADI ranks neighborhoods by socio-economic disadvantage based on measures of income, education, employment, and housing quality. ADIs are reported on a scale from 1 to 10, where higher scores indicate relative levels of socio-economic deprivation at the census block group level. The ADI data were retrieved at the block group level from the Neighborhood Atlas (

www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu, accessed on 30 March 2024). In addition to examining the location of cannabis dispensaries in relation to ADIs, heatmaps were generated to show where equity and non-equity dispensaries clustered.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Social Equity Policies

Social equity policies vary across states where recreational cannabis has been legalized. For this analysis, large U.S. cities (2020 population > 600,000) were identified in the twenty-four states that legalized recreational cannabis use between 2012 and 2023. This cutoff point was selected to limit the analysis to larger core cities where a critical mass of businesses could be identified, and where local governments were most likely to have the capacity to share data on cannabis policy. A total of twelve cities were identified in ten states that met these criteria to be included in the analysis. Data for the cities are summarized in

Table 1. Social equity policies were examined along three dimensions: (1) the social equity framework used for recreational cannabis businesses, (2) the criteria used to identify social equity entrepreneurs, and (3) the benefits available to social equity entrepreneurs. Cities were grouped based on the stage in the licensing process where social equity was considered. A comparison of these three groups provides insights into the degree to which the structure of social equity policies supports or undermines their reparative justice goals.

4.1.1. Open Application Process for Social Equity Applicants

The largest group of cities (N = 7) identified the social equity status of applicants for cannabis dispensary licenses at the initial stages of the application process. Generally, entrepreneurs were required to have a 51% or greater stake in businesses to be considered equity applicants. This status was taken into consideration when licenses were granted to applicants to varying degrees. Although the requirement for equity entrepreneurs to have a majority stake in businesses was uniform across states, other criteria differed. For example, three of the cities (New York, NY; Los Angeles, CA; and Boston, MA) had policies in place to license equity and non-equity businesses at a minimum of a 1:1 ratio. These policies were designed to provide equity applicants with equal access to the cannabis market. For the other four cities, providing equal access to the cannabis market was not part of the social equity framework.

There were other discrepancies across the cities in terms of the criteria used to identify social equity entrepreneurs. All the cities included reparative justice consideration in their criteria for identifying social equity entrepreneurs. These criteria included identifying entrepreneurs who had prior criminal convictions related to cannabis and who resided in neighborhoods disproportionately impacted by the war on drugs. However, all the cities used additional criteria to classify equity entrepreneurs. The inclusion of additional criteria diluted the reparative justice goals of cannabis policy. This was particularly problematic in the four cities where entrepreneurs were only required to meet one criterion to be classified as an equity business. New York City exemplified this problem since any applicant who met one of seven criteria (including gender, race, disabled veteran status, or residing in a low-income household) would be classified as a social equity applicant.

After being identified as a social equity applicant, there were a range of benefits available to equity entrepreneurs. The main benefits that entrepreneurs in this group received were being prioritized in the application review process and reductions in fees and licensing costs. In addition to these benefits, cities offered applicants technical assistance with the development of business plans, small business workshops, and other training. There were also limited loan and grant programs, which were dependent on annual allocations at the state level.

It is also noteworthy that the consideration of an entrepreneur’s equity status was a relatively recent innovation in the licensing process for recreational cannabis dispensaries. Social equity policies were introduced in Los Angeles and Boston in 2016, while early adopters of recreational cannabis like Seattle and Denver had not adopted restorative justice goals until 2023. In Denver, the social equity program only applied for licenses to deliver cannabis from a dispensary, and these licenses were only granted to equity entrepreneurs for the first four years of the program.

2 There was also variation in how social equity policies were designed and implemented across jurisdictions within individual states. In general, state legislation outlined broad parameters for cannabis legalization, leaving the implementation of policies to the discretion of local jurisdictions [

4,

34,

35]. For instance, three municipalities in California (Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Francisco) were examined in this analysis, and each had a distinct approach to implementing social equity policies. Combined the impacts of social equity policies were lessened both within and between states by the lag in their adoption, the dilution of restorative justice criteria when identifying equity entrepreneurs, the limited use of policies that required a 1:1 ratio of equity and non-equity licenses, and the decentralization of the policy implementation process.

4.1.2. Social Equity Lottery Cities

The second group of cities (N = 3) that identified the social equity status of applicants for cannabis dispensary licenses at the initial stages of the application process introduced an additional innovation. After identifying equity entrepreneurs, a small number of licenses were set aside for this group and awarded by lottery. Although distributing licenses by lottery did not guarantee that equity applicants would have equal access to the cannabis market, there were other benefits to this approach to licensing related to the reparative justice goals of cannabis social equity policies.

The cities (Chicago, Las Vegas, and Phoenix) that used a lottery to award social equity licenses adopted stronger reparative justice criteria to identify social equity entrepreneurs. The criteria focused on entrepreneurs who had prior criminal convictions for related cannabis and who resided in neighborhoods disproportionately impacted by the war on drugs. In addition to identifying a more discrete number of criteria, applicants had to meet most of the criteria to be eligible to enter the lottery. This guaranteed that a nexus would exist between equity entrepreneurs and reparative justice goals. Although the number of licenses awarded through the lottery was smaller (approximately 25–50 in each city since the licensing began), all licensees had access to benefits, including reductions in fees and licensing costs or technical assistance.

4.1.3. Eligibility for Benefits Determined after Licensing

The last group of cities (N = 2) did not identify the social equity status of applicants for cannabis dispensaries during the licensing process. For these cities, equity entrepreneurs were identified after licensing to determine eligibility to participate in social equity programs. Unlike the other two groups of cities, the social equity policy was not designed to provide equity entrepreneurs with priority in the licensing process or lower the bar to enter the cannabis market in other ways during the license application process. In addition, the degree to which social equity policies targeted entrepreneurs to achieve reparative justice varied.

At one end of the spectrum, Chicago and San Francisco emphasized reparative justice criteria when making social equity benefits available to entrepreneurs after licensing. Their criteria focused on entrepreneurs who had prior criminal convictions for related cannabis and who resided in neighborhoods disproportionately impacted by the war on drugs. In contrast, Portland placed less emphasis on reparative justice when identifying social equity businesses after licensing. The lack of emphasis on restorative justice in social equity policy was consistent with other cities that were early adopters of cannabis liberalization laws. Although being an equity entrepreneur was not considered in the application process for a cannabis dispensary license, a similar menu of benefits became available to equity entrepreneurs after receiving a license. Equity entrepreneurs in these cities were eligible for reductions in fees and licensing costs, and they had access to technical assistance and other small business programs.

4.2. Spatial Analysis of Equity and Non-equity Businesses

Equity and non-equity businesses were mapped for the subset of cities (N = 3) to gain insights into how the geography of cannabis businesses furthers or hampers the core social and economic equity goals of laws. The subset of cities was selected based on the availability of data identifying businesses by their street address and social equity status.

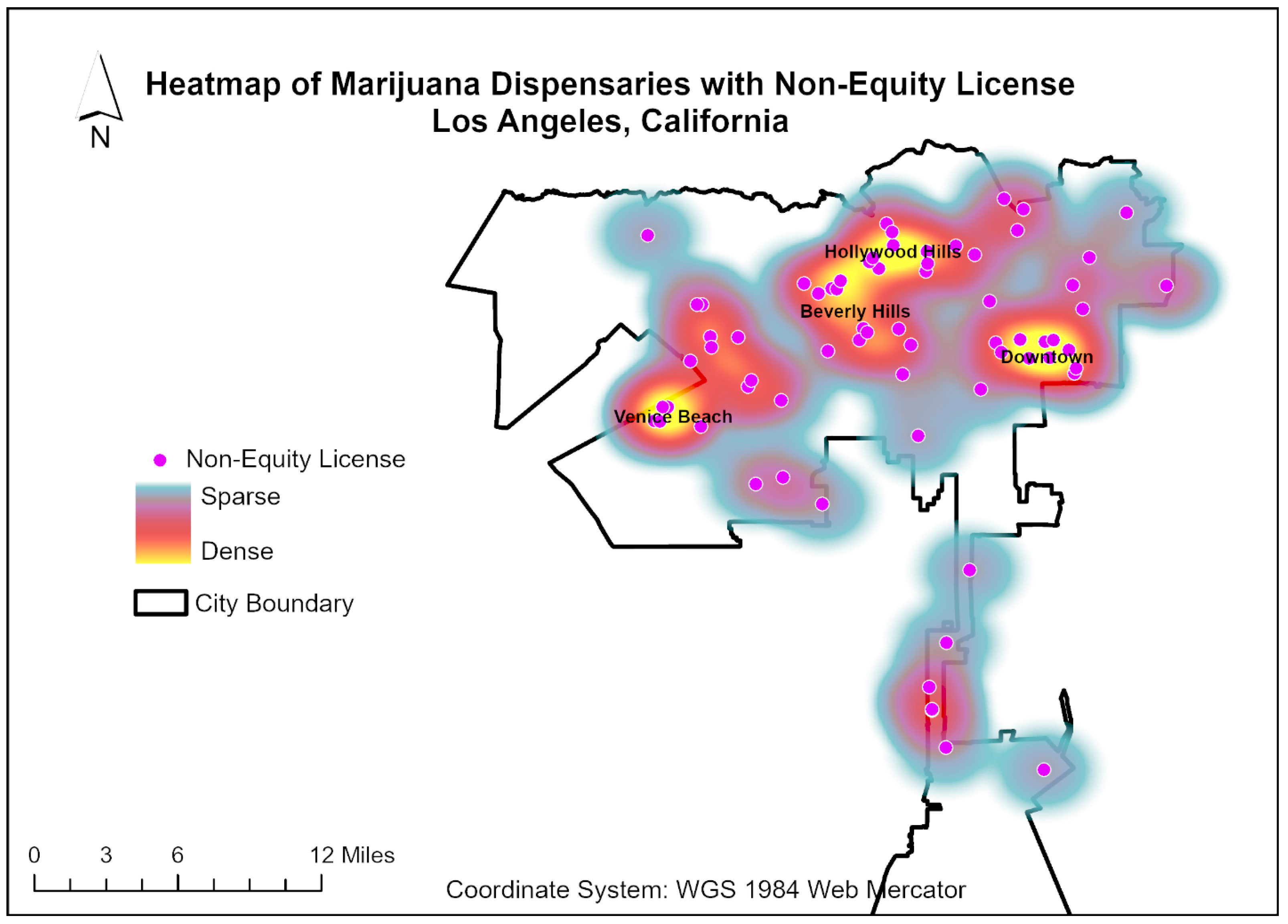

3 For each city, three maps were generated. The first map overlays the location of equity and non-equity recreation cannabis dispensaries on 2021 ADIs at the census block group level. ADIs are reported on a scale from 1 to 10, where higher scores indicate relative levels of socio-economic deprivation. The second and third are heat maps that show the relative density of cannabis dispensaries in census block groups. The second map displays clusters of cannabis dispensaries identified as social equity businesses. The third map displays clusters of cannabis dispensaries that we have not classified as social equity businesses.

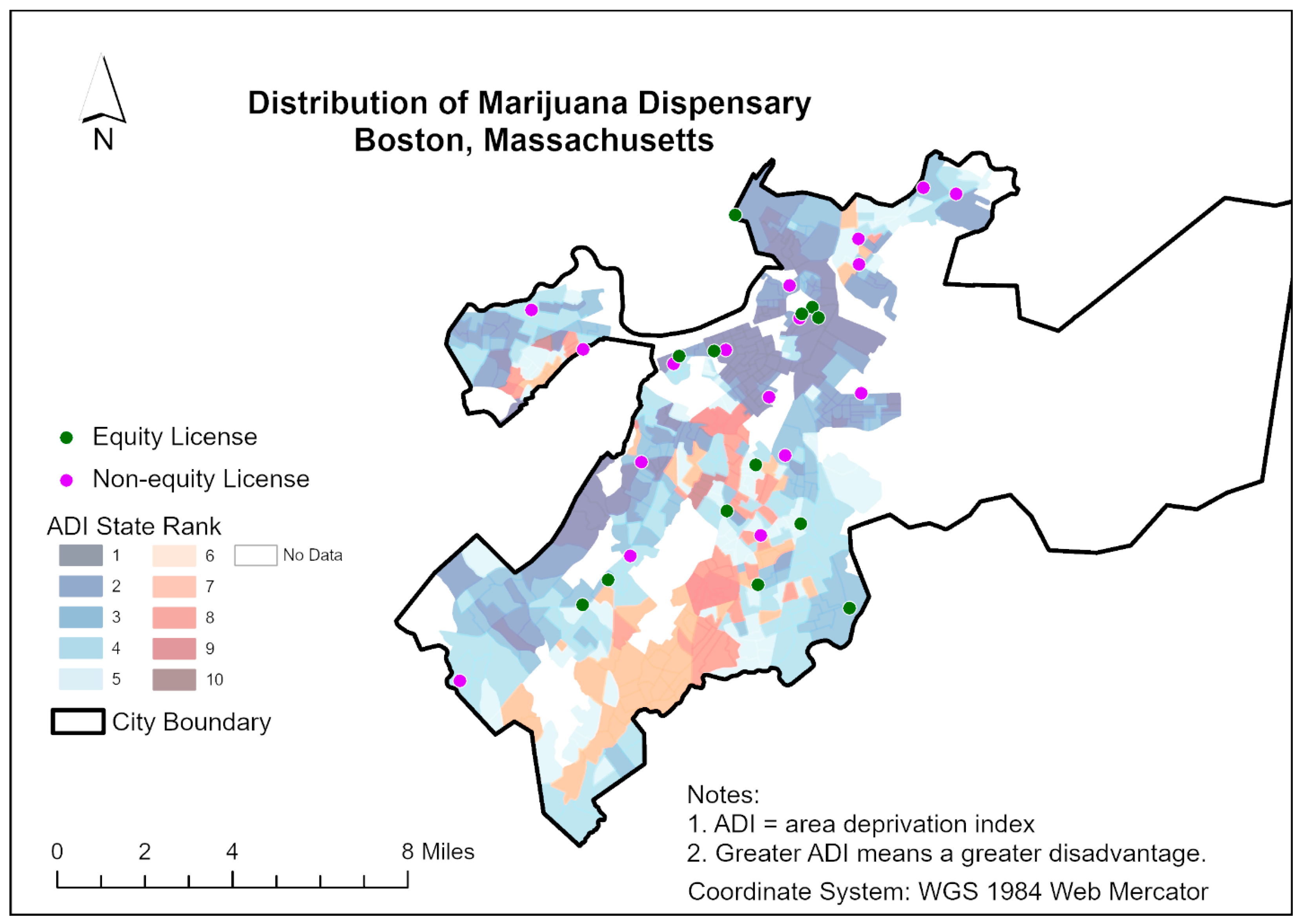

4.2.1. Boston

Maps were generated for the City of Boston based on September 2023 data supplied by the Mayor’s Office of Economic Inclusion. Recreational cannabis was legalized by a ballot measure in 2016 in Massachusetts, and implementation of the law was decentralized to localities. The City of Boston identifies equity entrepreneurs during the licensing process for cannabis dispensaries. To be classified as an equity entrepreneur, applicants must have a majority interest in a business and meet three of the seven criteria used in the screening process (see

Table 1). The City of Boston maintains a list of approved applications and issues licenses to operate cannabis dispensaries on a 1:1 basis. By design, this licensing process is intended to provide equity and non-equity entrepreneurs with similar access to the recreational cannabis market. To further level the playing field, equity applicants receive exclusive access to financial and technical assistance offered by the City’s cannabis equity program.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of cannabis dispensaries in Boston operated by equity (N = 11) and non-equity entrepreneurs (N = 16).

4 The location of dispensaries is overlayed on ADI measurements at the census block group level. The average ADI for the location of dispensaries operated by equity entrepreneurs was 3.36. The average ADI for dispensaries operated by non-equity entrepreneurs was 3.06. Independent sample

t-tests were run comparing neighborhood ADIs for equity and non-equity entrepreneurs, and there were no statistically significant differences (t = 0.561, df = 25,

p = 0.610).

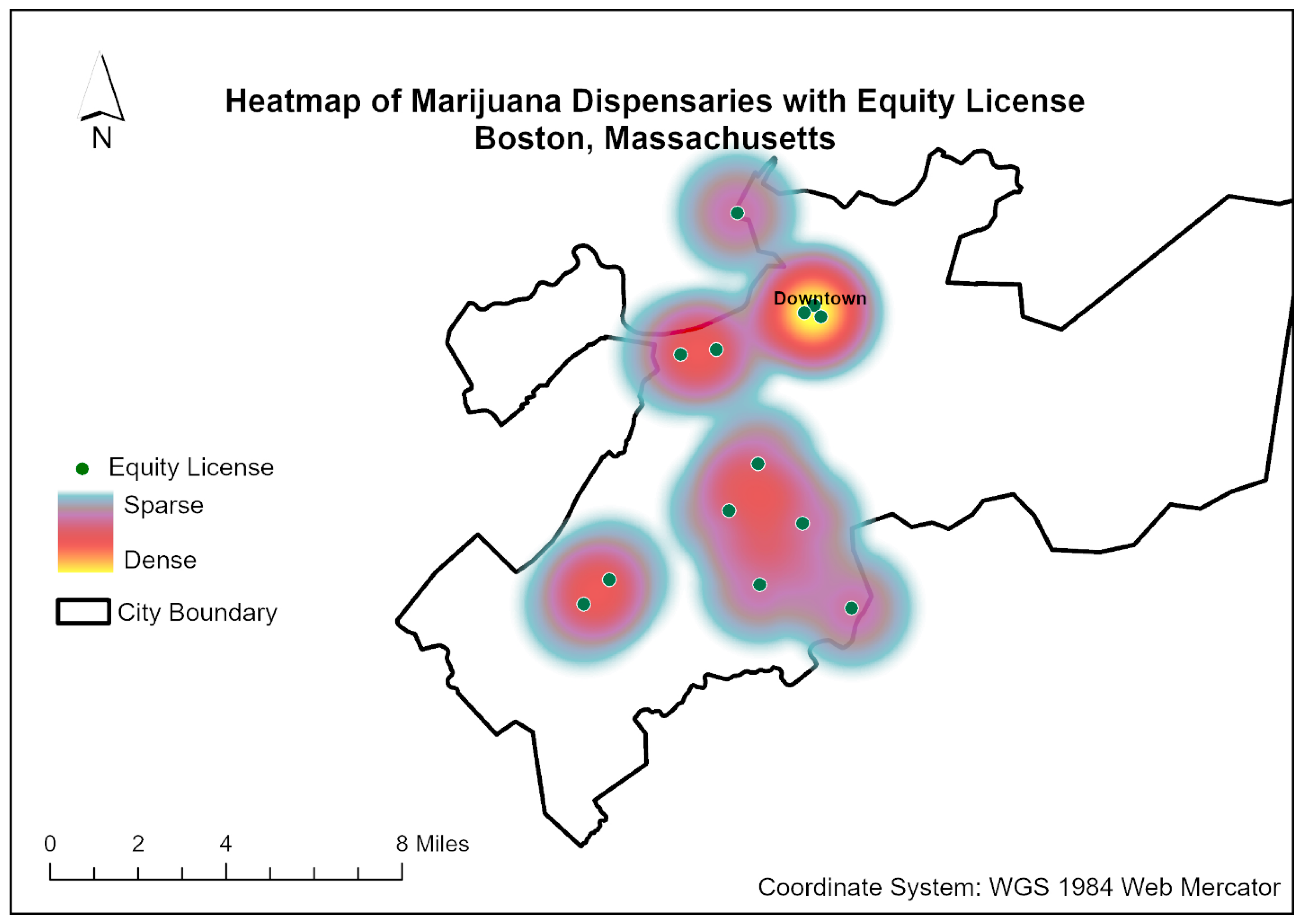

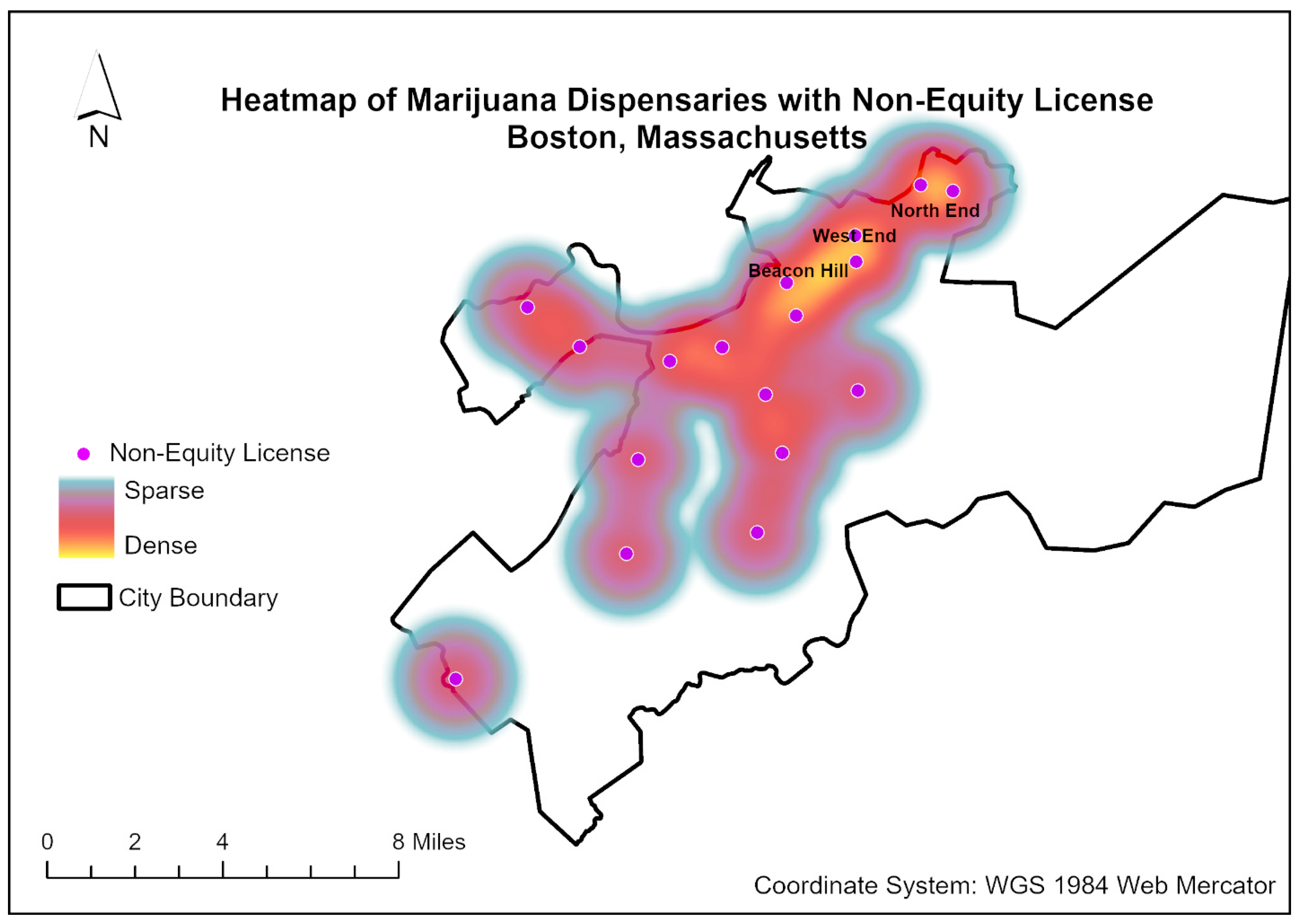

Although the analysis of ADIs showed no significant differences in the location of cannabis dispensaries in terms of the socio-economic makeup of the census block groups they were located in, heatmaps were generated for equity and non-equity businesses to determine if there were other differences identified in the spatial distribution where they clustered.

Figure 2 displays clusters of cannabis dispensaries operated by equity entrepreneurs. This map showed that the densest cluster of dispensaries operated by this type of entrepreneur was in downtown Boston. Equity businesses had access to this heavily trafficked commercial and tourist area in Boston. Other equity businesses were in areas with less commercial traffic and tourism.

Figure 3 displays clusters of cannabis dispensaries operated by non-equity entrepreneurs. This map showed that the densest cluster of dispensaries operated by this type of entrepreneur was in Boston’s high-traffic commercial and tourist areas such as Beacon Hill, the North End, and the West End. Despite similarities in ADI, non-equity businesses had greater access to more heavily trafficked commercial and tourist areas in Boston.

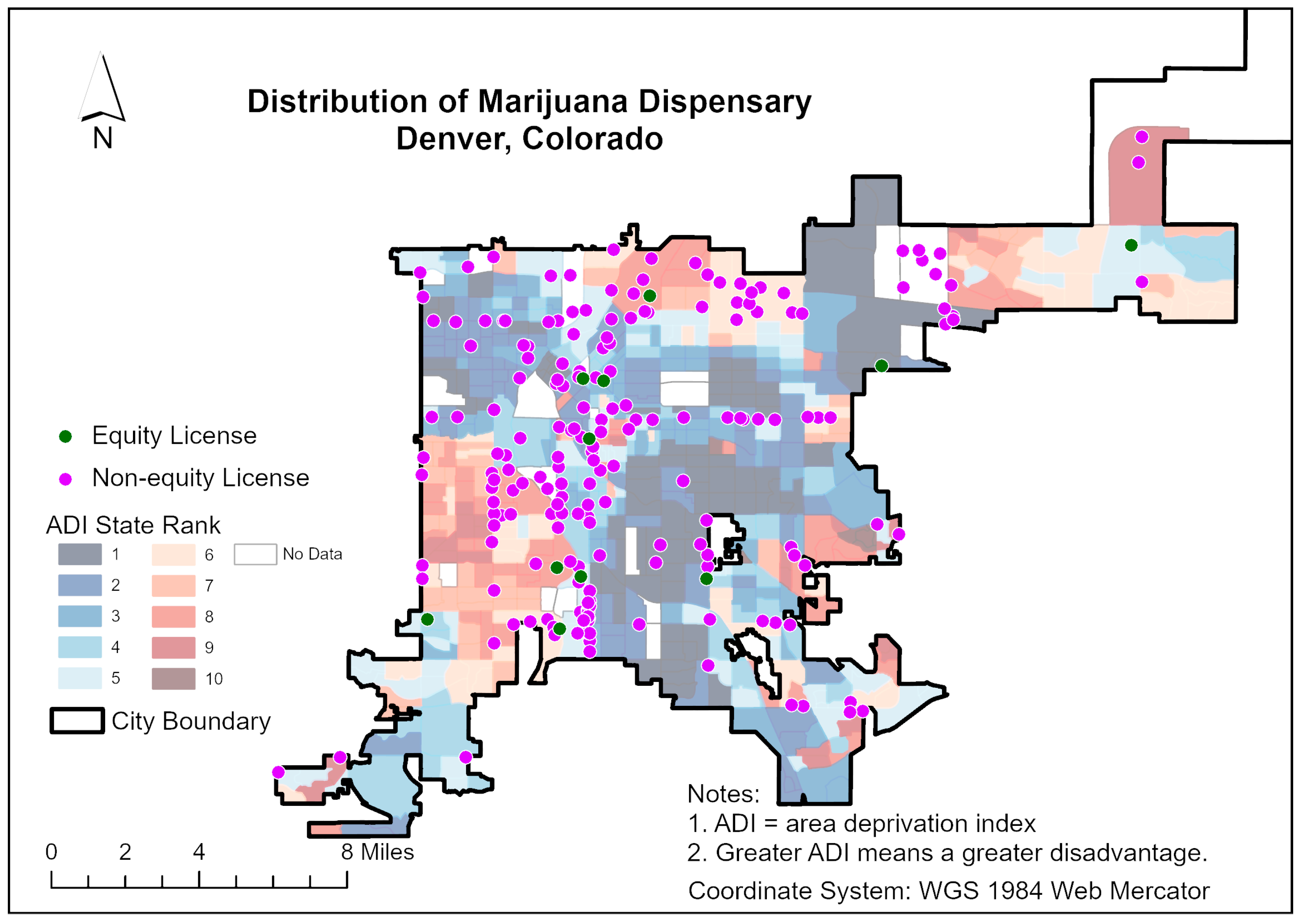

4.2.2. Denver

Maps were generated for the City of Denver based on January 2024 data supplied by the City and County of Denver from the Department of Excise and Licenses. Recreational cannabis was legalized by a ballot measure in 2012 in Colorado; it was one of the first states to legalize recreational marijuana, and implementation of the law was decentralized to localities. Despite being passed in 2012, social equity policies were not incorporated into the City of Denver’s cannabis ordinances until 2023. This was consistent with other early adopters of laws legalizing recreational cannabis in states like Washington and Oregon. Beginning in 2023, Denver took the equity status of entrepreneurs into consideration. The adoption of social equity policies coincided with the City’s addition of a new category of licensing for recreation cannabis, delivery businesses. A central component of Denver’s social equity strategy was to only issue licenses to deliver cannabis to equity applicants for the first four years of the policy’s rollout. To be classified as an equity entrepreneur, applicants must have a majority interest in a business and meet one of the four criteria used in the screening process (see

Table 1). It is notable that the four criteria used to screen applicants align with restorative justice goals. By design, this licensing process is intended to provide equity entrepreneurs with exclusive access to the delivery segment of the recreational cannabis market until 2027 in order to correct a lack of equity considerations in past licensing practices. To further level the playing field, equity applicants are eligible for waivers and reduced fees for business licensing and permitting processes.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of cannabis dispensaries in Denver operated by equity (N = 11) and non-equity entrepreneurs (N = 183). The location of dispensaries is overlayed on ADI measurements at the census block group level. The average ADI for the location of dispensaries operated by equity entrepreneurs was 4.36. The average ADI for dispensaries operated by non-equity entrepreneurs was 4.79. Independent sample t-tests were run comparing neighborhood ADIs for equity and non-equity entrepreneurs, and there were no statistically significant differences (t = −0.606, df = 192,

p = 0.545).

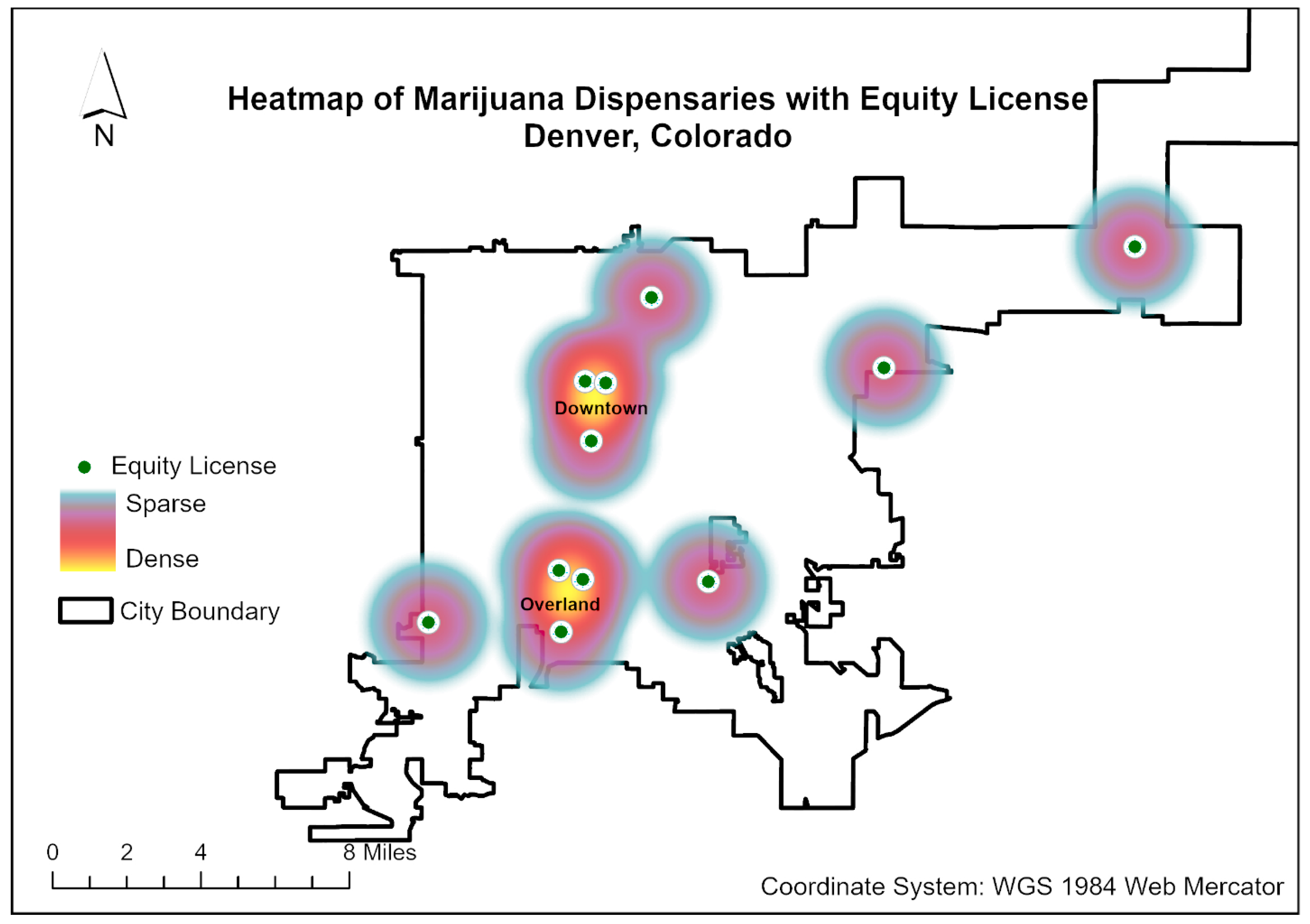

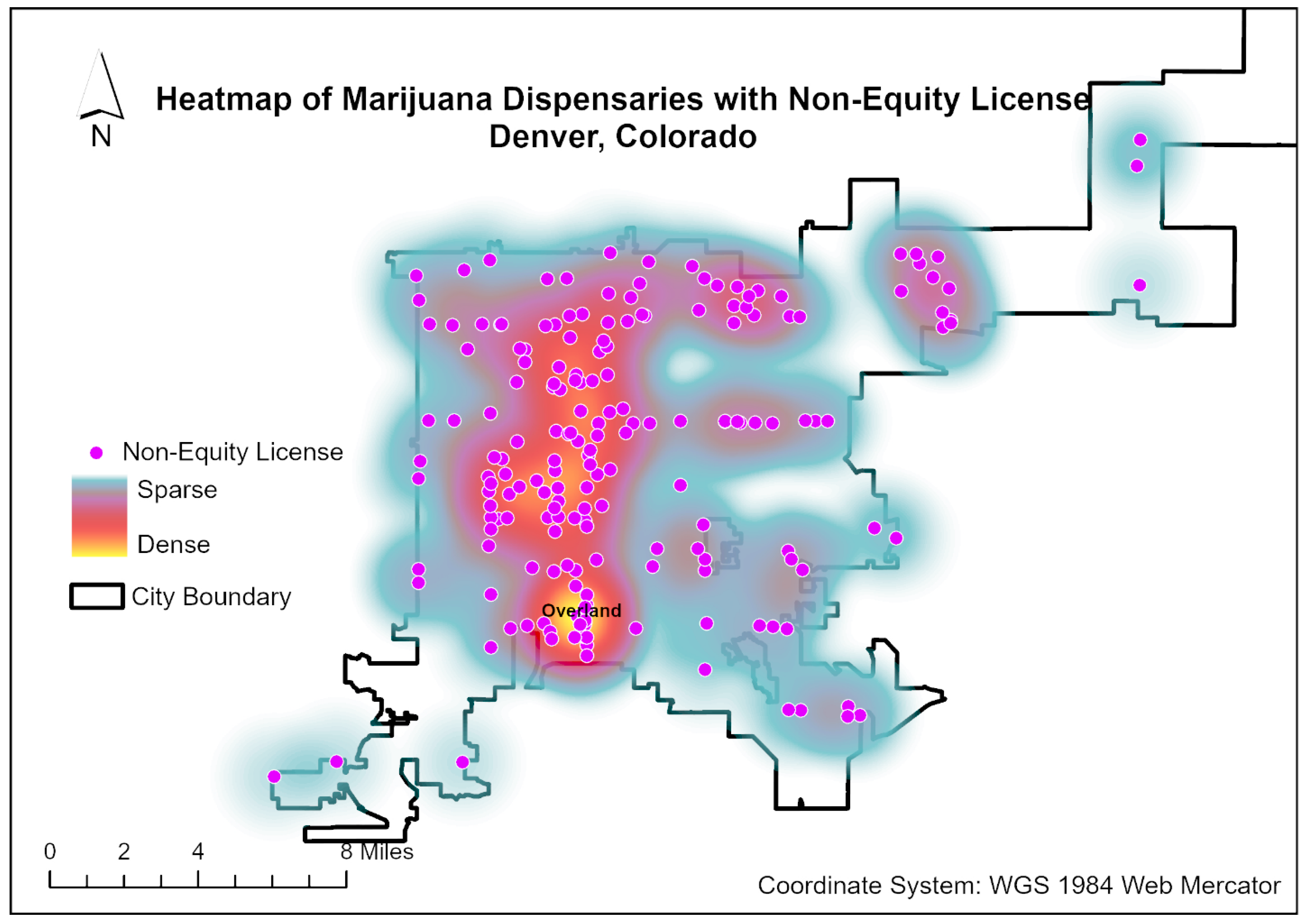

Although the analysis of ADIs showed no significant differences in the location of cannabis dispensaries, heatmaps were generated for equity and non-equity businesses to determine if there were differences in where they clustered.

Figure 5 displays clusters of cannabis dispensaries operated by equity entrepreneurs. This map showed two dense clusters of dispensaries operated by this type of entrepreneur. One was near downtown, and another was in the Ruby Hill/Overland neighborhoods, which are older residential areas that have gentrified. These clusters suggest that Denver’s cannabis dispensaries operated by equity entrepreneurs have access to commercial and tourist areas as well as gentrifying suburbs.

Figure 6 displays clusters of cannabis dispensaries operated by non-equity entrepreneurs. This map showed that the densest cluster of dispensaries operated by this type of entrepreneur was in the Ruby Hill/Overland neighborhoods. It is noteworthy that cannabis dispensaries operated by non-equity entrepreneurs outnumbered those operated by equity entrepreneurs by a 16.6:1 ratio. Non-equity dispensaries were also ubiquitous across Denver. In this context, the heatmaps suggest that the recent adoption of exclusive equity licenses for cannabis delivery represents an effort to give equity entrepreneurs greater access to heavily trafficked commercial and tourist areas. However, these measures are being adopted in a context where there may already be a saturation of non-equity businesses.

4.2.3. Los Angeles

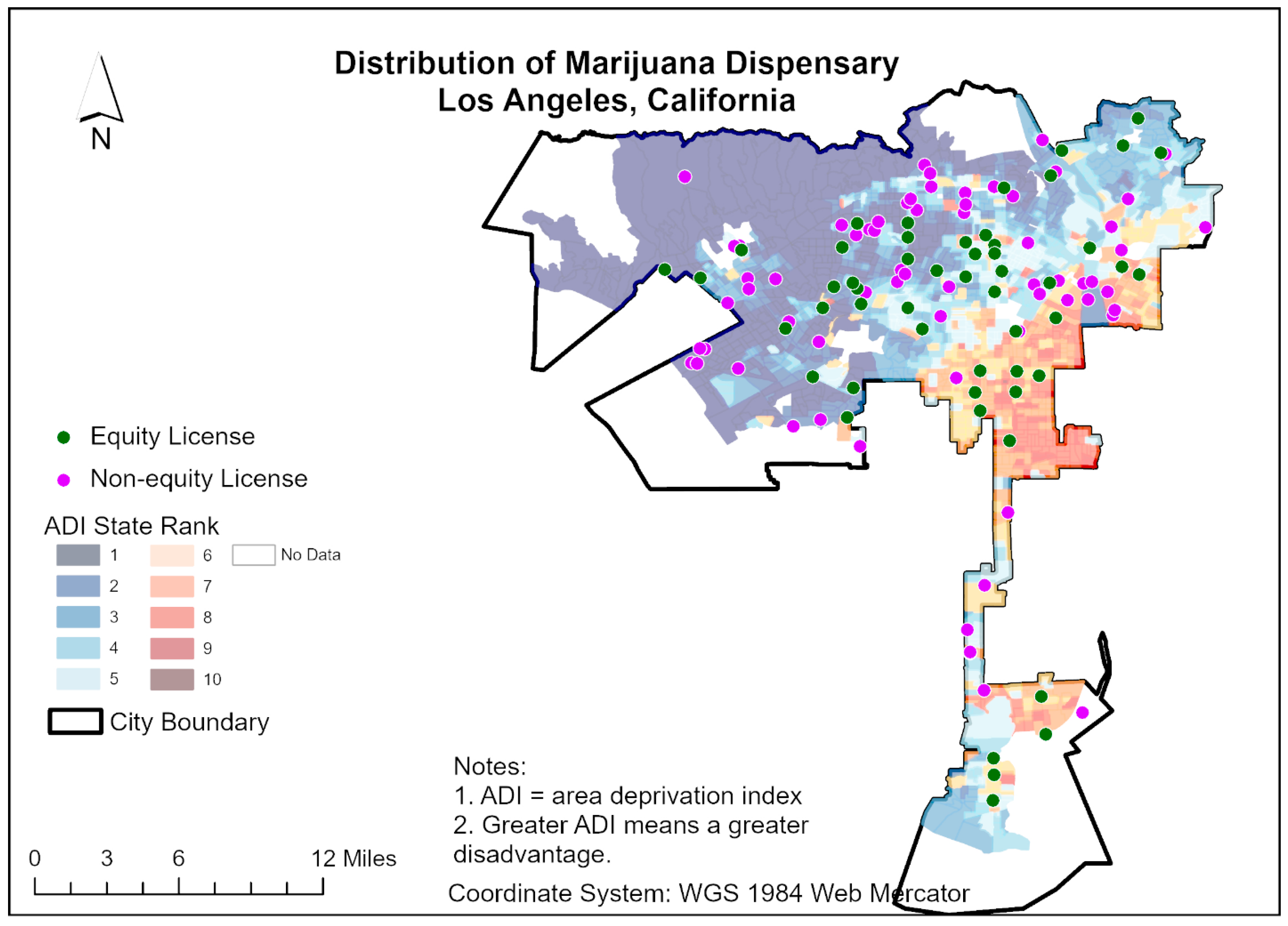

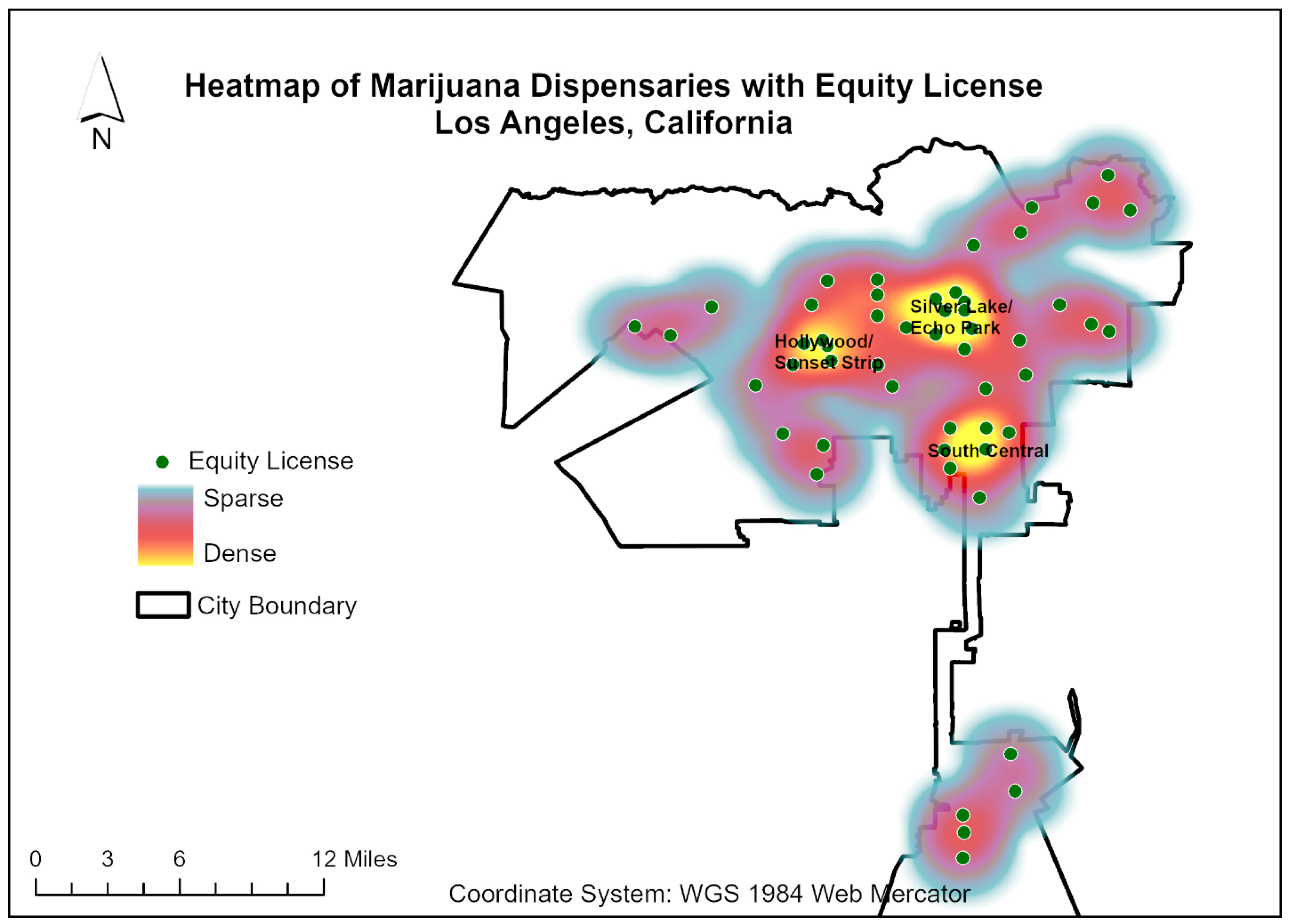

Maps were generated for the City of Los Angeles based on January 2024 data supplied by the City of Los Angeles, Department of Cannabis Regulation. Recreational cannabis was legalized by a ballot measure in 2016 in California, and implementation of the law was decentralized to localities. To be classified as an equity entrepreneur, applicants must have a majority interest in a business and meet one of the three criteria used in the screening process (see

Table 1). It is notable that the three criteria used to screen applicants align with restorative justice goals. To further level the playing field, equity applicants are eligible for waivers and reduced fees for business licensing and permitting, grants and loans, and technical assistance offered through the City’s social equity program.

Figure 7 shows the distribution of cannabis dispensaries in Los Angeles operated by equity (N = 51) and non-equity entrepreneurs (N = 69). The location of dispensaries is overlayed on ADI measurements at the census block group level. The average ADI for the location of dispensaries operated by equity entrepreneurs was 4.35. The average ADI for dispensaries operated by non-equity entrepreneurs was 3.55. Independent sample t-tests were run comparing neighborhood ADIs for equity and non-equity entrepreneurs, and there were no statistically significant differences (t = 1.92, df = 118,

p = 0.057).

Although the analysis of ADIs showed no significant differences in the location of cannabis dispensaries, heatmaps were generated for equity and non-equity businesses to determine if there were differences in where they clustered.

Figure 8 displays clusters of cannabis dispensaries operated by equity entrepreneurs. This map showed three dense clusters of dispensaries operated by this type of entrepreneur. One was near the Vermont-Slauson and Florence neighborhoods in Los Angeles. This area is a predominantly black and Latino area in South Central Los Angeles. It was a focal point of the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Another cluster of equity businesses was in the West Lake, Silver Lake, and Echo Park neighborhoods. These neighborhoods are recently gentrified. The third cluster of equity businesses was in the core part of the Hollywood-Sunset strip area. These clusters suggest that Los Angeles’ cannabis dispensaries operated by equity entrepreneurs have access to a spectrum of commercial and tourist areas, gentrifying neighborhoods, and South Central.

Figure 9 displays clusters of cannabis dispensaries operated by non-equity entrepreneurs in Los Angeles. This map showed three dense clusters of dispensaries operated by this type of entrepreneur. One was centered in downtown Los Angeles and the downtown entertainment district. Another cluster of non-equity businesses was in the more affluent neighborhoods of Hollywood Hills and Beverly Hills. The third cluster of non-equity equity businesses was in the Venice Beach neighborhood. These clusters suggest that Los Angeles’ cannabis dispensaries operated by non-equity entrepreneurs have relatively greater access to commercial and tourist areas and more affluent parts of the city.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

The results from this analysis provide insights into the degree to which the implementation of social equity policies linked to cannabis has promoted restorative justice goals. The analysis focused on social equity measures designed to give people with prior cannabis convictions and members of communities adversely impacted by the war on drugs opportunities to operate recreational cannabis dispensaries. We identified a variety of strategies adopted by municipalities to achieve restorative justice goals. Incrementally, these goals have been incorporated into state laws and local ordinances, and the emphasis on achieving them has become more central over time. This is evident in the growing number of states including social equity policies in legislation legalizing recreational cannabis, and ongoing adaptations of these policies over time as best practices are incorporated. Our conclusions are based on an analysis of large cities, and we acknowledge that inferences and recommendations may not apply to other settings. With this limitation in mind, we offer some preliminary conclusions that provide a foundation for future analysis as additional data become available for analysis.

Our analysis revealed best practices across three dimensions of social equity policies. In terms of the social equity policy framework, we found that localities exhibited greater fidelity to redistributive justice goals when they considered the equity status of entrepreneurs during the licensing process for recreational dispensaries, required applicants to meet multiple criteria to be identified as an equity entrepreneur, and issued licenses for equity businesses on at least a 1:1 ratio with non-equity businesses. In terms of the criteria used to identify equity entrepreneurs, we found that localities that had a more discrete number of criteria focused on prior cannabis convictions and community impacts due to the war on drugs had greater fidelity to restorative justice goals. Finally, in terms of benefits for social justice entrepreneurs, we found that the adoption of more comprehensive packages of benefits indicated that localities had greater fidelity to restorative justice goals.

Our findings from the spatial analysis of recreational dispensary licensing add another dimension to the discussion of restorative justice. In addition to reaching parity in the number of licenses, social equity involves whether entrepreneurs have comparable access to markets. We examined this from two perspectives. First, we examined the degree to which equity and non-equity entrepreneurs had access to business locations in comparable neighborhoods based on socio-economic characteristics. We found that in the three cities where spatial analysis was carried out, all entrepreneurs had access to communities with similar ADIs. However, relative levels of neighborhood wealth and deprivation do not provide full information about the size of markets that businesses have access to. We used heatmaps to identify clusters of equity and non-equity cannabis dispensaries in the three cities examined. Then, we compared the neighborhoods in those clusters. Our findings suggested that non-equity cannabis dispensaries clustered in neighborhoods that had more access to commercial and tourist activity, as well as more affluent customers. For example, non-equity entrepreneurs had more access to Boston’s downtown and tourist market, Los Angeles’ downtown entertainment district, Venice Beach, and affluent consumers in Beverly Hills and the Hollywood Hills. Although Denver’s equity entrepreneurs had exclusive permission to deliver marijuana from a cluster of businesses in the city’s downtown area, they remained at a relative disadvantage in that market due to the predominance of non-equity entrepreneurs in that city. These observations are tentative but suggest that future research should examine market characteristics, access to consumers, and revenue from individual recreational cannabis dispensaries more systematically to determine if disparities exist between equity and non-equity businesses.

Considering these initial findings, we recommend that municipalities continue to amend social equity programs with three goals in mind. First, policies should base the designation of equity entrepreneurs on meeting specific criteria that target people with prior marijuana convictions and who are members of communities disproportionately impacted by the war on drugs. Localities should close loopholes that apply overly broad definitions to criteria for identifying equity entrepreneurs to maintain fidelity to restorative justice goals. Second, localities should focus their policies more on reaching and maintaining at least a 1:1 ratio of cannabis dispensaries operated by equity entrepreneurs and non-equity entrepreneurs. This is particularly needed in cities like Denver, where equity licensing was recently adopted and there are many pre-existing cannabis dispensaries operated by non-equity entrepreneurs. Moving forward, some cities need to be diligent about maintaining an equilibrium between equity and non-equity businesses, while other cities need to impose a moratorium on the licensing of new non-equity businesses until one is reached. Finally, localities need to enhance and better target technical support and other business assistance programs for equity entrepreneurs to ensure that they have greater access to the most desirable locations to operate businesses. In essence, there is a need across all existing social equity programs to assist equity entrepreneurs in opening businesses in neighborhoods where they will have access to large customer bases, tourists, and more affluent consumers. These recommendations build on observations in the literature that highlight the underrepresentation of equity entrepreneurs at all levels of the cannabis industry [

36], the unique challenges they face due to inconsistencies in federal and state regulations [

37,

38], and disparities in equity entrepreneurs’ access to the industry due to insufficient technical assistance and targeted grant and loan programs [

39].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L.P., R.M.S. and L.Y.; methodology, K.L.P., R.M.S. and L.Y.; formal analysis, K.L.P., R.M.S., L.Y., A.R.-V. and S.W.; data curation, K.L.P., A.R.-V. and S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, K.L.P. and R.M.S.; writing—review and editing, K.L.P., R.M.S. and A.R.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a research grant from the Baldy Center for Law & Social Policy at the University at Buffalo.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1. | At the time this article was written, the following states had passed legislation decriminalizing the recreational use of cannabis: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington. |

| 2. | There is ambiguity about the adoption of equity licenses for cannabis delivery businesses in Denver and the overall number of equity entrepreneurs. Our analysis suggested that delivery licenses were granted to entrepreneurs operating existing storefront cannabis dispensaries. Although Denver did not identify equity entrepreneurs prior to the issuance of delivery licenses, at least a partial count can be derived from those who were granted delivery licenses. However, this discrepancy in reporting is an acknowledged limitation in this analysis. |

| 3. | These three cities were the only ones in this study where municipalities maintained records of cannabis dispensaries operated by both equity and non-equity entrepreneurs with street addresses or other locational information that could be mapped and incorporated into the spatial analysis. |

| 4. | Boston issues recreational dispensary licenses on a 1:1 ratio for equity and non-equity entrepreneurs. The disparity between the number of equity (N = 11) and non-equity businesses in Map 1 reflects the closure of some establishments after licensing. |

References

- Hrdinová, J.; Ridgway, D. Mapping Cannabis Social Equity: Understanding How Ohio Compares to Other States’ Post-Legalization Policies to Redress Harms; Ohio State University Drug Enforcement and Policy Center: Columbus, OH, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Neeley, G.W.; Richardson, L.E. Cannabis policy adaptation: Exploring Frameworks of State Policy Characteristics. Public Adm. Q. 2023, 47, 253–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reefer Madness; Directed by Louis J. Gasnier; G&H Productions: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1936.

- Silverman, R.M.; Patterson, K.L.; Williams, S.S. Don’t Fear the Reefer?: The Social Equity and Community Planning Implications of New York’s Recreational Cannabis Law on Underserved Communities. J. Policy Pract. Res. 2023, 4, 150–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, T.M.; Moscowitz, L.; Wan, A. The Marijuana user in US news media: An examination of visual stereotypes of race, culture, criminality and normification. Vis. Commun. 2019, 19, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudak, J. Marijuana: A Short History, 2nd ed.; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Payan, D.D.; Brown, P.; Song, A.V. County-level recreational marijuana policies and local policy changes in Colorado and Washington State (2012–2019). Milbank Q. 2021, 99, 1132–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, A. Zoning, race, and Marijuana: The unintended consequences of proposition 64. Lewis Clark Law Rev. 2019, 23, 939–966. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri, S.; Momsivais, P.; McDonell, M.G.; Amram, O. Availability of licensed cannabis businesses in relation to area deprivation in Washington state: A spatiotemporal analysis of cannabis business presence between 2014 and 2017. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2019, 38, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polson, M. Buttressed and breached: The exurban fortress, cannabis activism, and the drug war’s shifting political geography. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2020, 38, 626–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggess, L.N.; Perez, D.M.; Cope, K.; Root, C.; Stretesky, P.B. Do medical marijuana centers behave like locally undesirable land uses?: Implications for the geography of health and environmental justice. Urban Geogr. 2014, 35, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, C.; Gruenewald, P.J.; Freisthler, B.; Ponicki, W.R.; Remer, L.G. The economic geography of medical marijuana dispensaries in California. Int. J. Drug Policy 2014, 25, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, J.; Ross, E. Planning for marijuana: The cannabis conundrum. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2014, 80, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilley, J.A.; Hitchcock, L.; McGroder, N.; Greto, L.A.; Richardson, S.M. Community-level policy responses to state marijuana legalization in Washington State. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 42, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, G.; Kocak, O.; Kovacs, B. Co-opts or coexist?: A study of medical cannabis dispensaries’ identity-based responses to recreational-use legalization in Colorado and Washington. Organ. Sci. 2018, 29, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, C.; Freisthler, B.; Ponicki, W.R.; Gaidus, A. The impacts of marijuana dispensary density and neighborhood ecology of marijuana abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 154, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilmer, B. How will cannabis legalization affect health, safety, and social equity outcomes?: It largely depends on the 14 Ps. Am. J. Drugs Alcohol 2019, 45, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, R.A.; Rodriquez, A.; Parast, L.; Pedersen, E.R.; Tucker, J.S.; Troxel, W.M.; Kraus, L.; Davis, J.P.; D’Amicom, E.J. Associations between young marijuana outcomes and availability of medical marijuana dispensaries and storefront sinage. Addictions 2019, 114, 2162–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, C.A.; Cowan, B.W.; Rosenman, R.E. Geographical access to recreational marijuana. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2020, 39, 778–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hust, S.J.T.; Willoughby, J.F.; Li, J.; Couto, L. Youth’s proximity to marijuana retailers and advertisements: Factors associated with Washington State adolescents’ intentions to use marijuana. J. Health Commun. 2020, 25, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, K.T.; Galea, S.; Ahern, J.; Tract, M.; Vlahov, D. The built environment and alcohol consumption in urban neighborhoods. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007, 91, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.M.; Simmel, C.; Peterson, N.A. Neighborhood alcohol outlets density and rates of child abuse and neglect: Moderating effects of access to substance abuse services. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.; Law, J.; Cooke, M. Exploring and visualizing the small-area-level socioeconomic factors, alcohol availability and built environment influences of alcohol expenditure for the City of Toronto: A spatial analysis approach. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2019, 39, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, M.L.; Albani, T.; Keller-Hamilton, B.; Lu, B.; Roberts, M.E.; Craigmile, P.F.; Browing, C.; Xi, W.; Ferketich, A.K. Exposures to the tobacco retail environment among adolescent boys in urban and rural environments. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2019, 45, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereria, T.F.P.D. Reflecting on drug tourism and its future challenges. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2020, 10, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.K.; O’Leary, J.; Miller, J. From forbidden fruit to the goose that lays the golden eggs: Marijuana tourism in Colorado. Sage Open 2016, 6, 2158244016679213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doussard, M. The other green job: Legal marijuana and the promise of consumption-driven economic development. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilmer, B.; Caulkins, J.P.; Kilborn, M.; Priest, M.; Warren, K.M. Cannabis legalization and social equity: Some opportunities, puzzles, and tradeo-offs. Boston Univ. Law Rev. 2021, 100, 1003–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, N.N. Lost boys, invisible men: Racialized policy feedback after marijuana legalization. Public Adm. Q. 2023, 47, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Noue, G.R. Who counts?: Determining the availability of minority businesses for public contracting after Croson. Harv. J. Law Public Policy 1998, 21, 793–834. [Google Scholar]

- La Noue, G.R.; Sullivan, J.C. Deconstructing affirmative action categories. Am. Behav. Sci. 1998, 41, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, S.W. Minority procurement: Beyond affirmative action to economic empowerment. Rev. Black Political Econ. 1999, 27, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Noue, G.R. Policies to ensure group equality in public contracting in four countries. Int. J. Divers. Organ. Communities Nations 2009, 8, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, J.; Singu-Eryilmaz, Y. Understanding local control in the wake of state adult-use cannabis liberalization: A content analysis of state statutes. Public Adm. Q. 2023, 47, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.; Goodman, N.; Kavousi, P.; Giamo, T.; Arnold, G.; Plakias, Z. Economic governance in cannabis: The implementation of polycentric governance in Mendocino County. Public Adm. Q. 2023, 47, 300–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doonan, S.M.; Johnson, J.K.; Caislin, F.; Flores, A.; Joshi, S. Racial equity in cannabis policy: Diversity in the Massachusetts adult-use industry at 18-months. Cannabis 2022, 5, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, J.; Bloomberg, S.; Lawarence, G.; Smith, A.J. Regulating Cannabis Interstate Commerce: Perspectives on How the Federal Government Should Respond; The Ohio State University, Moritz College of Law, Drug Enforcement and Policy Center: Columbus, OH, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, K.C.; Thompson, A.J.; Iannacchione, B.M.; Evans, M.K. Crime, law, and legalization: Perceptions of Colorado Marijuana dispensary owners and managers. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 2019, 30, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaskewich, D.M. State licenses for medical marijuana dispensaries: Neighborhood-level determinants of applicant quality in Missouri. J. Cannabis Res. 2024, 6, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).