What Do We Know about Age Management Practices in Public and Private Institutions in Scandinavia?—A Public Health Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Dimensions of Age Management

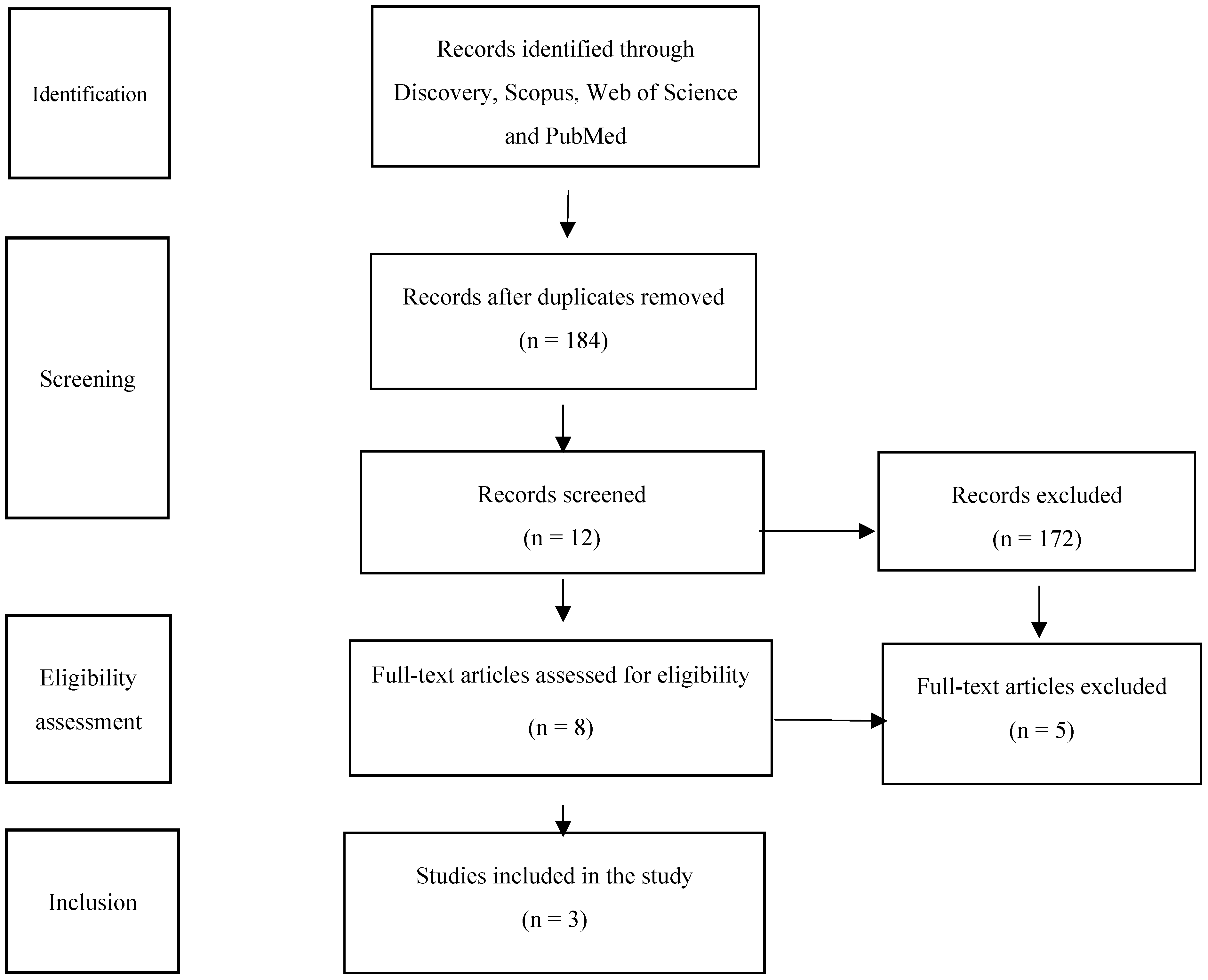

3. Material and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Study Characteristics and Main Findings

4.2. AM Dimensions Addressed in the Reviewed Studies

5. Discussion and Conclusions: Age Management Implications for the Health and Well-Being of Older Workers from a Public Health Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ball, C. The Age and Employment Network Defining Age Management: Information and Discussion Paper; TAEN: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–8. Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/37409352/defining-age-management-taen (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Fabisiak, J.; Prokurat, S. Age management as a tool for the demographic decline in the 21st century: An overview of its characteristics. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2012, 8, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, D.R.C.; Fracasso, N.V.; Costa, R.G.; Rossaneis, M.Â.; Aroni, P.; Haddad, M.D.C.F.L. Age management practices toward workers aged 45 years or older: An integrative literature review. Rev. Bras. Med. Trab. 2020, 18, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A. Combating Age Barriers in Employment—A European Research Report; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions: Dublin, Germany, 1997; Available online: https://edz.bib.uni-mannheim.de/www-edz/pdf/ef/97/ef9718en.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Walker, A. The emergence of age management in Europe. Int. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 10, 685–697. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, D.E.; Sousa-Poza, A. Economic consequences of low fertility in Europe. In FZID Discussion Papers; Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:100-opus-4225 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Kiss, M.; Negreiro, M.; Niestadt, M.; Niijenhuis, C.; Van Lierop, C.; Van der Linde, A. Demographic Outlook for the European Union; EPRS: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; European Parliamentary Research Service; pp. 1–72. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/729461/EPRS_STU(2022)729461_EN.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Ebbinghaus, B.; Gronwald, M. The changing public–private pension mix in Europe: From path dependence to path departure. In The Varieties of Pension Governance: Pension Privatization in Europe; Ebbinghaus, B., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbinghaus, B. Multiple Hidden Risks for Older People: The Looming Pension Crisis Following This Pandemic. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2020, 1–6. Available online: https://bit.ly/3n8oWEo (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Ebbinghaus, B. Inequalities and poverty risks in old age across Europe: The double-edged income effect of pension systems. Soc. Policy Adm. 2021, 55, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, A.C. Aging population and effects on labour market. Procedia Econ. Finance 2012, 1, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyar, S.; Ebeke, C.; Shao, X. The Impact of Workforce Aging on European Productivity; International Monetary Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–29. Available online: http://www.Imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/wp16238.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Villosio, C.; Di Pierro, D.; Giordanengo, A.; Pasqua, P.; Ricciardi, M. Working Conditions of an Ageing Workforce; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions: Dublin, Germany, 2008; pp. 1–84. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Sotomayor, I.; Laka, J.P.; Aguado, R. Workforce Ageing and Labour Productivity in Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuběnka, M.; Slavίček, O. Relationship between level of prosperity and failure prediction. In SGEM-Political Sciences, Law, Finance, Economics and Tourism Conference Proceedings; book 2; STEF92 Technology Ltd.: Sofie, Bulgaria, 2016; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Skowron-Grabowska, B.; Mesjasz-Lech, A. Konkurencyjne uwarunkowania zarządzania zasobami kadrowymi w przedsiębiorstwach w kontekście dostępu do rynku pracy. Przegląd Organ. 2016, 10, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzen-Mitka, S.M.; Skibinski, A. Multifaceted character of the issues of management. Pol. J. Manag. 2016, 16, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addeco, H.R. It’s Time to Manage Age. Overview of Labour Market Practices Affecting Older Workers in Europe 2011. Available online: https://www.age-platform.eu/adecco-white-paper-on-corporate-age-management/ (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Halvorsen, B.E. Senior Citizens: Work and Pensions in the Nordics; Elanders Sverige: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019; pp. 1–86. [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen, B.E. High and rising senior employment in the Nordic countries. Eur. J. Workplace Innov. 2021, 6, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, K.; Östergren, P.O.; Kadefors, R.; Albin, M. Has the participation of older employees in the workforce increased? Study of the total Swedish population regarding exit from working life. Scand. J. Public Health 2016, 44, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health—Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2008. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1 (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Naegele, G.; Bauknecht, J. Mobilizing the potential of active aging in Europe. In National Policy Report Work Package 3-Task Force 2; University of Shefield: Sheffield, UK, 2015; pp. 1–208. Available online: https://www.ffg.tu-dortmund.de/cms/de/Projekte/Abgeschlossene_Projekte/2017/MOPACT_-_Mobilising_the_Potential_of_Active_Ageing_in_Europe/MOPACT_WP3_Task2_2_National_Policy_Report.pdf; (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Scoppeta, A.; Jodar, L.A. Career Management and Age Management; ESF transnational platform: Vienna, Austria, 2019; pp. 1–19. Available online: https://european-social-fund-plus.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-06/Paper_Career%20Management_final_June%202019.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Egdell, V.; Maclean, G.; Raeside, R.; Chen, T. Age management in the workplace: Manager and older worker accounts of policy and practice. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 784–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, T.M.; Kraiger, K.; Henry, K.L. Age-Related Changes on the Effects of Job Characteristics on Job Satisfaction: A Longitudinal Analysis. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2020, 91, 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naegele, G.; Walker, A. Ageing in Employment—A European Code of Good Practice; Eurolink Age: Brussels, Belgium, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff, L.; Franke, A.; Wanka, A. Resonant Retiring? Experiences of Resonance in the Transition to Retirement. Front. Sociol. 2021, 26, 723359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.; Liu, S.; Shultz, K.S. Bridge employment and retirees’ health: A longitudinal study. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, M.; Leidner, D.E. Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.T.S. A literature review on knowledge management in organizations. Res. Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, S.; Shujahat, M.; Hussain, S.; Nawaz, F.; Wang, M.; Ali, M.; Tehseen, S. Knowledge management, organizational commitment, and knowledge-worker performance: The neglected role of knowledge management in the public sector. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2019, 25, 923–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaim, H.; Muhammed, S.; Tarim, M. Relationship between knowledge management processes and performance: Critical role of knowledge utilization in organizations. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 17, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Comite, U.; Yucel, A.G.; Liu, X.; Khan, M.A.; Husain, S.; Oláh, J. Unleashing the importance of TQM and knowledge management for organizational sustainability in the age of circular economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K. Role of leadership in knowledge management: A study. J. Knowl. Manag. 2008, 12, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, M.; Paulsen, J.M. National strategy for supporting school principal’s instructional leadership: A Scandinavian approach. J. Educ. Adm. 2019, 57, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsbergis, P.A. The changing organization of work and the safety and health of working people: A commentary. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 45, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagan, C. Time, money, and the gender order: Work orientations and working-time preferences in Britain. Gend. Work. Organ. 2001, 8, 239–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, L. The effects of working time on productivity and firm performance: A Research synthesis paper. In Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 33; International Labor Organization (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, P.; Song, Y.; Fang, M.; Chen, X. Creating an age-inclusive workplace: The impact of HR practices on employee work engagement. J. Manag. Organ. 2023, 29, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustajab, D.; Bauw, A.; Rasyid, A.; Irawan, A.; Akbar, M.A.; Hamid, M.A. Working from home phenomenon as an effort to prevent COVID-19 attacks and its impacts on work productivity. Int. J. Appl. Bus. 2020, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Sharma, M. Work from home: Benefits and challenges. Manag. Dyn. 2022, 22, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algahtani, A. Are leadership and management different? A review. J. Manag. Policies Pract. 2014, 2, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Răducan, R.; Răducan, R. Leadership and management. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 149, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunnenburg, F.C. Leadership versus management: A key distinction—At least in theory. Int. J. Manag. Bus. Adm. 2011, 14, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bunjak, A.; Bruch, H.; Černe, M. Context is key: The joint roles of transformational and shared leadership and management innovation in predicting employee IT innovation adoption. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 66, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; Van Muijen, J.J.; Koopman, P.L. Transactional versus transformational leadership: An analysis of the MLQ. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1997, 70, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackoff, R.L. Transformational leadership. Strategy Leadersh. 1999, 27, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellazzo, L.; Bruni, E.; Zampieri, R. The role of leadership in a digitalized world: A review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuknor, S.C.; Bhattacharya, S. Inclusive leadership: New age leadership to foster organizational inclusion. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2022, 46, 771–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelloRusso, S.; Miraglia, M.; Borgogni, L. Reducing organizational politics in performance appraisal: The role of coaching leaders for age-diverse employees. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, R.W. An ergonomic approach to the aging workforce utilizing this valuable resource to best advantage by integrating ergonomics, health promotion and employee assistance programs. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2008, 23, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D.; Muscat, D.M. Health promotion glossary 2021. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 36, 1578–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, R.; Warren, N.; Robertson, M.; Faghri, P.; Cherniack, M.; CPH–New Research Team. Workplace health protection and promotion through participatory ergonomics: An integrated approach. Public Health Rep. 2009, 124 (Suppl. 1), 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, H. Compatibility as guiding principle for ergonomics work design and preventive occupational health and safety. Z. Für Arbeitswissenschaft 2022, 76, 243–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faez, E.; Zakerian, S.A.; Azam, K.; Hancock, K.; Rosecrance, J. An assessment of ergonomics climate and its association with self-reported pain, organizational performance, and employee well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punnett, L.; Cherniack, M.; Henning, R.; Morse, T.; Faghri, P.; CPH–New Research Team. A conceptual framework for integrating workplace health promotion and occupational ergonomics programs. Public Health Rep. 2009, 124 (Suppl. 1), 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furunes, T.; Mykletun, R.J. Age Management in Norwegian Hospitality Businesses. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2005, 5, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furunes, T.; Mykletun, R.J.; Solem, P.E. Age management in the public sector in Norway: Exploring managers’ decision latitude. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 1232–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.; Moberg, R. Age management in Danish companies: What, how and how much? Nord. J. Work. Life Stud. 2012, 2, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: PRISMA Statement. J. Clinical. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulders, J.O.; Henkens, K.; Schippers, J. European Top Managers’ Age-Related Workplace Norms and Their Organizations’ Recruitment and Retention Practices Regarding Older Workers. Gerontologist 2017, 57, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, K.; Mulders, J.O.; Henkens, K. The Proactive Shift in Managing an Older Workforce 2009–2017: A Latent Class Analysis of Organizational Policies. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 1515–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomé, M.W.; Borell, J.; Håkansson, C.; Nilsson, K. Attitudes toward elderly workers and perceptions of integrated age management practices. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2020, 26, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Earl, C. Making the case for older workers. Manag. Rev. 2016, 27, 14–28. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24892941 (accessed on 15 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Bogataj, D.; Bogataj, M. Age management transportation workers in global supply chains. IFAC-Pap. Online 2018, 51, 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seid, J.; Neiva, E.R.; Faiad, C.; Murta, S.G. Age diversity management in organization scale: Development and evidence of validity. Psico-USF 2022, 27, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcaletti, F. Age management and sustainable careers for the improvement of the quality of ageing work. Act. Ageing Healthy Living 2014, 203, 134–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bockman, S.; Sirotnik, B. The aging workforce: An expanded definition. Bus. Renaiss. Q. 2008, 3, 129. [Google Scholar]

- Lazazzara, A.; Karpinska, K.; Henkens, K. What factors influence training opportunities for older workers? Three factorial surveys exploring the attitudes of HR professionals. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2154–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, E.M.; Hanley, K.; Jenkins, A.K.; Chan, C. Managing the Ageing Workforce in the East and the West, 1st ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Picchio, M.; Van Ours, J.C. Retaining through Training Even for Older Workers. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2013, 32, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naegele, G.; Walker, A. A Guide to Good Practice in Age Management; Eurofound: Dublin, Ireland, 2006; Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1836145/a-guide-to-good-practice-in-age-management/2578997/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Loretto, W.; Vickerstaff, S.; White, P. The Future for Older Workers: New Perspectives; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, K.E.; Giandrea, M.D.; Quinn, J.F. Is bridge job activity overstated? Work. Ageing Retire. 2018, 4, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Jones, G.R. Understanding and Managing Organizational Behavior, 6th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, K.; Gedikli, C.; Watson, D.; Semkina, A.; Vaughn, O. Job design, employment practices and well-being: A systematic review of intervention studies. Ergonomics 2017, 60, 1177–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskel, J.; Martin, J. Economic Inactivity and the Labour Market Experience of the Long-Term Sick. 2022. Available online: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/people/j.haskel/document/9802/Haskel%20Martin%20sickness%20inactivity%20v2/?Haskel%20Martin%20sickness%20inactivity%20v2.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- European Network for Workplace Health Promotion. The Luxembourg Declaration on Workplace Health Promotion; European Network for Workplace Health Promotion: Perugia, Italy, 1997; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pieper, C.; Schröer, S.; Eilerts, A.L. Evidence of workplace interventions—A systematic review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimani, A.; Aboagye, E.; Kwak, L. The effectiveness of workplace nutrition and physical activity interventions in improving productivity, work performance and workability: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Promoting an Age-Inclusive Workforce: Living, Learning and Earning Longer; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Breij, S.; Huisman, M.; Deeg, D.J.H. Work characteristics and health in older workers: Educational inequalities. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söderbacka, T.; Nyholm, L.; Fagerström, L. Workplace interventions that support older employees’ health and work ability—A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, D.E. Human resource management and employee well-being: Towards a new analytic framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macassa, G.; Tomaselli, G. Socially responsible human resources management and stakeholders’ Health Promotion: A conceptual paper. Southeast. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) and Year | Study | Country | Objective(s) | Sample/Methods | Summary of Findings (Including Age Management Dimensions Addressed in the Study) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Furunes, T.; Mykletun, R.J., 2005 [58] | Age Management in Norwegian Hospitality Businesses, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism | Norway | To investigate how managers direct issues of an ageing workforce and whether this has implications for the hospitality industry | (n = 20) Qualitative interviews | It was more positive to have a balanced workforce consisting of younger and older workers. In the same study, no explicit age barriers regarding recruitment were found, although no manager was planning to recruit older workers. There was a positive complementarity in younger and older workers working together in the industry. Also, the study found that managers who were positive about the complementarity of younger and older workers in the industry were also positive towards older workers. In addition, the study included the age management dimensions of job recruitment, training, development, and work ability promotion. Job recruitment: The recruitment procedures were found to be different for full-time and part-time jobs. For part-time jobs and season employment contracts, e.g., chambermaids and banquette waiters, employees were often recruited through friends or through announcements at local education. Nevertheless, there were no age limits when new employees were recruited. Training, lifelong learning, development, and promotion: None of the organisations included in the study offered training that was fit for older employee needs. However, informants felt that there was no need for diverse training, as all employees performed the same job, also stating that age was not decisive to which training should be offered. Flexible work, promotion and work design were also found to be important by informants. |

| Furunes, T.; Mykletun R. J.; Solem, P.E., 2011 [59] | Age management in the public sector in Norway: exploring managers’ decision latitude. | Norway | To assess the extent to which managers accept responsibility for age management issues, how do they perceive their decision latitude (options and constraints) with regard to age management and how does this perceived decision latitude vary in relation to a range of organisational and managerial variables? | (n = 672) Survey | The results found that the management attitudes were the main predictors as they explained 22% of the variance in decision latitude. In addition, the same study indicated that changing managers’ attitudes and providing access to human and financial resources seemed to the most important criteria that influenced managers’ perceived decision latitude, contributing to the retention of older employees. No specific age dimensions were investigated in the study. |

| Jensen, P.; Moberg, R., 2012 [60] | Age management in Danish companies: what, how and how much? | Denmark | To investigate Danish employers’ behaviour in the area of active aging, which is made topical by demographic aging. In addition, the study aimed to describes age management practices and explains why some companies were more prone to employ age management than others. | (n = 609) Survey | The results further indicated that employers in larger companies were positive to older employees regarding their loyalty, reliability, and social skills. In 47% of companies, the introduction of flexible working hours was the most common AM policy, and 28% had asked an older worker to postpone their retirement for at least 1 year in the past 2 years. No specific age dimensions were investigated in the study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Macassa, G.; Chowdhury, E.H.; Barrena-Martinez, J.; Soares, J. What Do We Know about Age Management Practices in Public and Private Institutions in Scandinavia?—A Public Health Perspective. Societies 2024, 14, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14060085

Macassa G, Chowdhury EH, Barrena-Martinez J, Soares J. What Do We Know about Age Management Practices in Public and Private Institutions in Scandinavia?—A Public Health Perspective. Societies. 2024; 14(6):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14060085

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacassa, Gloria, Ehsanul Huda Chowdhury, Jesus Barrena-Martinez, and Joaquim Soares. 2024. "What Do We Know about Age Management Practices in Public and Private Institutions in Scandinavia?—A Public Health Perspective" Societies 14, no. 6: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14060085

APA StyleMacassa, G., Chowdhury, E. H., Barrena-Martinez, J., & Soares, J. (2024). What Do We Know about Age Management Practices in Public and Private Institutions in Scandinavia?—A Public Health Perspective. Societies, 14(6), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14060085