Social Factors Associated with Insecurity in Nigerian Society

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Review

2.2. Theoretical Foundations

2.3. Empirical Review

2.3.1. Review of Effects of Insecurity on Economic Growth

2.3.2. Evaluation of Causes of Insecurity in the Society

3. Methodology

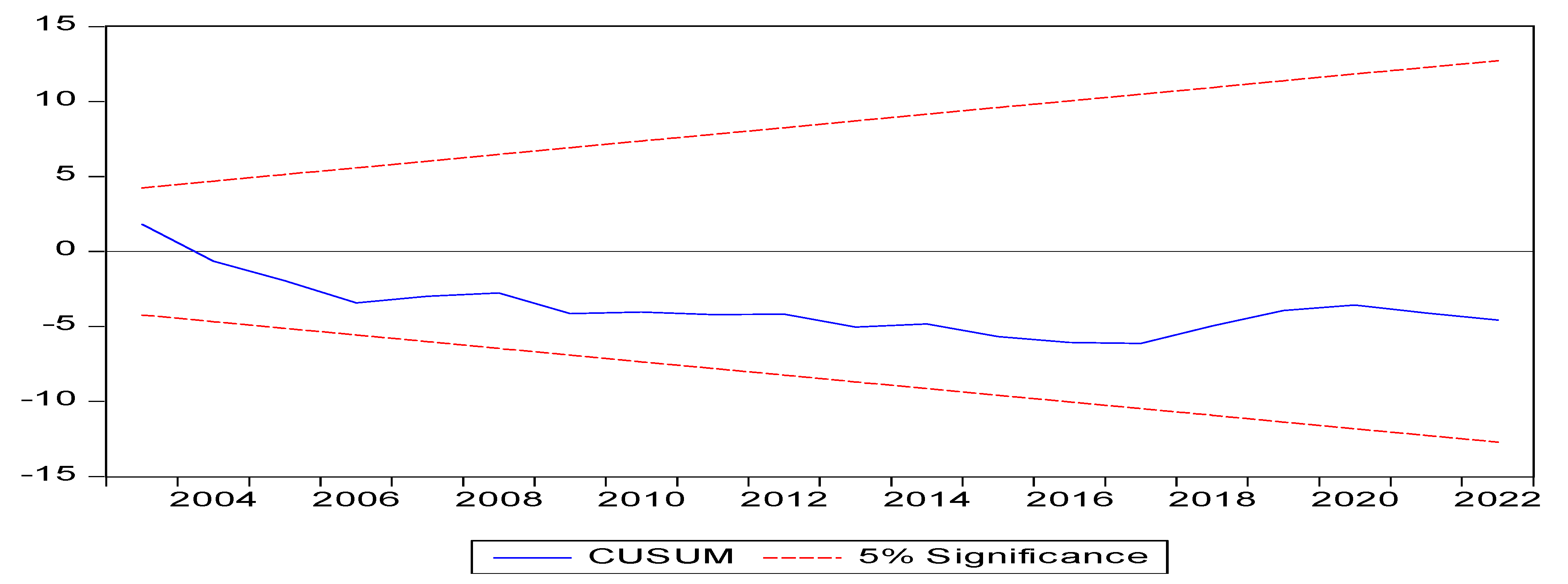

4. Result

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Charas, M.T. Insecurity in Northern Nigeria: Cause, Consequences and Resolutions. Int. J. Peace Confl. Stud. 2015, 2, 23–36. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:195476190 (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Zubairu, N. Rising insecurity in Nigeria: Causes and solution. J. Stud. Soc. Sci. 2020, 19, 1–11. Available online: https://infinitypress.info/index.php/jsss/article/view/1979 (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Udoh, E.W. Insecurity in Nigeria: Political, religious and cultural implications. J. Philos. Cult. Relig. 2015, 5, 1–7. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234694644.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Shavah, E.A. Effect of insecurity on Nigeria’s economic growth. Bingham Univ. J. Account. Bus. 2022, 7, 205–215. Available online: http://35.188.205.12:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/772 (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Nkwatoh, L.S.; Hiikyaa, A.N. Effect of insecurity on economic growth in Nigeria. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2018, 1, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozoigbo, B.I. Insecurity in Nigeria: Genesis, consequences and panacea. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2019, 4, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Terrorism Index. Global Terrorism Index 2022: Sub-Saharan Africa Emerges as Global Epicenter of Terrorism, as Global Deaths Decline. 2022. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-terrorism-index-2022 (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Akinyetun, T.S.; Ebonine, V.C.; Ambrose, I.O. Unknown gunmen and insecurity in Nigeria: Dancing on the brink of state fragility. Secur. Def. Q. 2023, 42, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awojobi, O.N. The socio-economic implications of Boko Haram insurgency in the North East of Nigeria. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. 2014, 11, 144–150. Available online: https://www.issr-journals.org/xplore/ijisr/0011/001/IJISR-14-233-02.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Bilgel, F.; Karahasan, B.C. Thirty Years of Conflict and Economic Growth in Turkey: A Synthetic Control Approach. LSE Europe in Question Discussion Paper Series. LEQS Paper No. 112/2016. 2016. Available online: http://aei.pitt.edu/93636/1/LEQSPaper112.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Blomberg, S.B.; Hess, G.D.; Weerapana, A. Economic conditions and terrorism. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2004, 20, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, O.; Esther, B.; Ifeannyi, A.E. Evaluation of the effect of insecurity on Nigeria Economic growth. Discovery 2022, 58, 235–243. Available online: https://www.discoveryjournals.org/discovery/current_issue/v58/n315/A10.pdf? (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Dauda, M. The Effect of Boko Haram Crisis on Socio-Economic Activities in Yobe State. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Invent. 2014, 1, 251–257. Available online: https://valleyinternational.net/index.php/theijsshi/article/download/24/25/49 (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Fatima, M.; Latif, M.; Chugtai, M.; Nazik, H.; Aslam, S. Terrorism and its Impact on Economic Growth: Evidence from Pakistan and India. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2014, 22, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaibulloev, K.; Sandler, T. The Impact of Terrorism and Conflicts on Growth in Asia. Econ. Politics 2009, 21, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, T.; Enders, W. An economic perspective on transnational terrorism. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2004, 20, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabir, H.; Naeem, A.; Ihtsham, P. Impact of Terrorism on Economic Development in Pakistan. Pak. Bus. Rev. 2015, 2015, 701–722. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271079363_Impact_of_Terrorism_on_Economic_Development_in_Pakistan (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Ndubuisi-Okolo, P.U.; Anigbuogu, T. Insecurity in Nigeria: The implications of Industrialization and sustainable development. Int. J. Res. Bus. Stud. Manag. 2019, 6, 7–16. Available online: https://www.ijrbsm.org/papers/v6-i5/2.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Beland, D. Insecurity, Citizenship, and Globalization: The multiple faces of state protection. Sociol. Theory 2005, 23, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achumba, O.S.; Ighomereho, M.O.M.; Akpor, R. Security Challenges in Nigeria and The Implications for Business Activities and Sustainable Development. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 4, 79–99. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234645825.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Udoh, B.; Prince, A.; Udo, E.; Kelvin-Iioafu, L. Insecurity on Economic and Business Climate; Empirical Evidence from Nigeria. Int. J. Supply Oper. Manag. 2019, 6, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojuade, J.I.; Alayande, E. Insecurity and Nigeria’s socio-economic development: A Survey. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 1, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, E.E.; Duke, O.O.; Ogbinyi, O.J. The implications of food insecurity, poverty and Hunger on Nigeria’s national security. Asian Res. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2017, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduwole, T.A. Youth unemployment and poverty in Nigeria. Int. J. Sociol. Anthropol. Res. 2015, 1, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, U.C.; Onyema, O.A.; Basey, U.S. Poverty and insecurity in Nigeria: An Empirical study. Int. J. Leg. Stud. 2019, 2, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsowon, F.I. Root causes of security challenges in Nigeria and solutions. Int. J. Innov. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Res. 2021, 9, 174–180. Available online: https://seahipaj.org/journals-ci/dec-2021/IJISSHR/full/IJISSHR-D-18-2021.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Tilly, C. Review of Why Men Rebel, by T. R. Gurr. J. Soc. Hist. 1971, 4, 416–420. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3786479 (accessed on 14 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gurr, T.R. Why Men Rebel, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, I.E.; Iredia, O.D.; Wayas, M.M. Effect of insecurity on sustainable national Economic development of Nigeria. Niger. J. Res. Prod. 2022, 25, 1–9. Available online: https://www.globalacademicgroup.com/journals/nigerian%20journal%20of%20research%20and%20production%20/Effect%20of%20Insecurity.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Blomberg, S.B.; Hess, G.D.; Weerapana, A. An Economic Model of Terrorism. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci. 2004, 21, 17–28. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26273516 (accessed on 5 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Bellows, J.; Miguel, E. War and Local Collective Action in Sierra Leone. J. Public Econ. 2009, 93, 1144–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, P.; Hoeffler, A. On the Incidence of Civil War in Africa. J. Confl. Resolut. 2002, 46, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, K.F.; Mckinney, L.A. Disease, war, hunger, and deprivation: A cross-national investigation of the determinants of life expectancy in less-developed and sub-Saharan African nations. Sociol. Perspect. 2012, 55, 421–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdamar, O. Theorizing Terrorist Behaviour: Major Approachesins and their Characteristics. Def. Against Terror. Rev. 2008, 1, 89–101. Available online: http://ozgur.bilkent.edu.tr/download/06Theorizing%20Terrorist%20Behavior%20Major%20Approaches%20and%20Their%20Characteristics.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Krueger, A.B. What Makes a Terrorist: Economics and the Roots of Terrorism (New Edition); Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7t153 (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Onime, B.E. Insecurity and economic growth in Nigeria: A diagnostic review. Eur. Sci. J. 2018, 14, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mukolu, M.O.; Ogodor, B.N. Insurgency and its implication on Nigeria economic Growth. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 7, 492–501. Available online: https://isdsnet.com/ijds-v7n2-06.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Nikšić, R.M.; Dragičević, D.; Barkiđija, S.M. Causality between Terrorism and FDI in Tourism: Evidence from Panel Data. Economies 2019, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, S.; Ricco, J. Shock and awe? Fiscal consequences of terrorism. Empir. Econ. 2020, 58, 723–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrique-de-Lara-Peñate, C.; Gallego, M.S.; Valle, E.V. The economic impact of Global uncertainty and security threats on international tourism. Econ. Model. 2022, 113, 105892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, U.V.; Oladipo, O.; Onugha, C.B. Impact of insecurity on economic activities in Awka Metropolis. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 9, 137–150. Available online: https://journals.aphriapub.com/index.php/SSR/article/view/2052 (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Osberg, L. Economic Insecurity; Discussion Paper from University of New South Wales; Social Policy Research Centre: Sydney, Australia, 1998; Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/wopsprcdp/0088.htm (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of Level relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

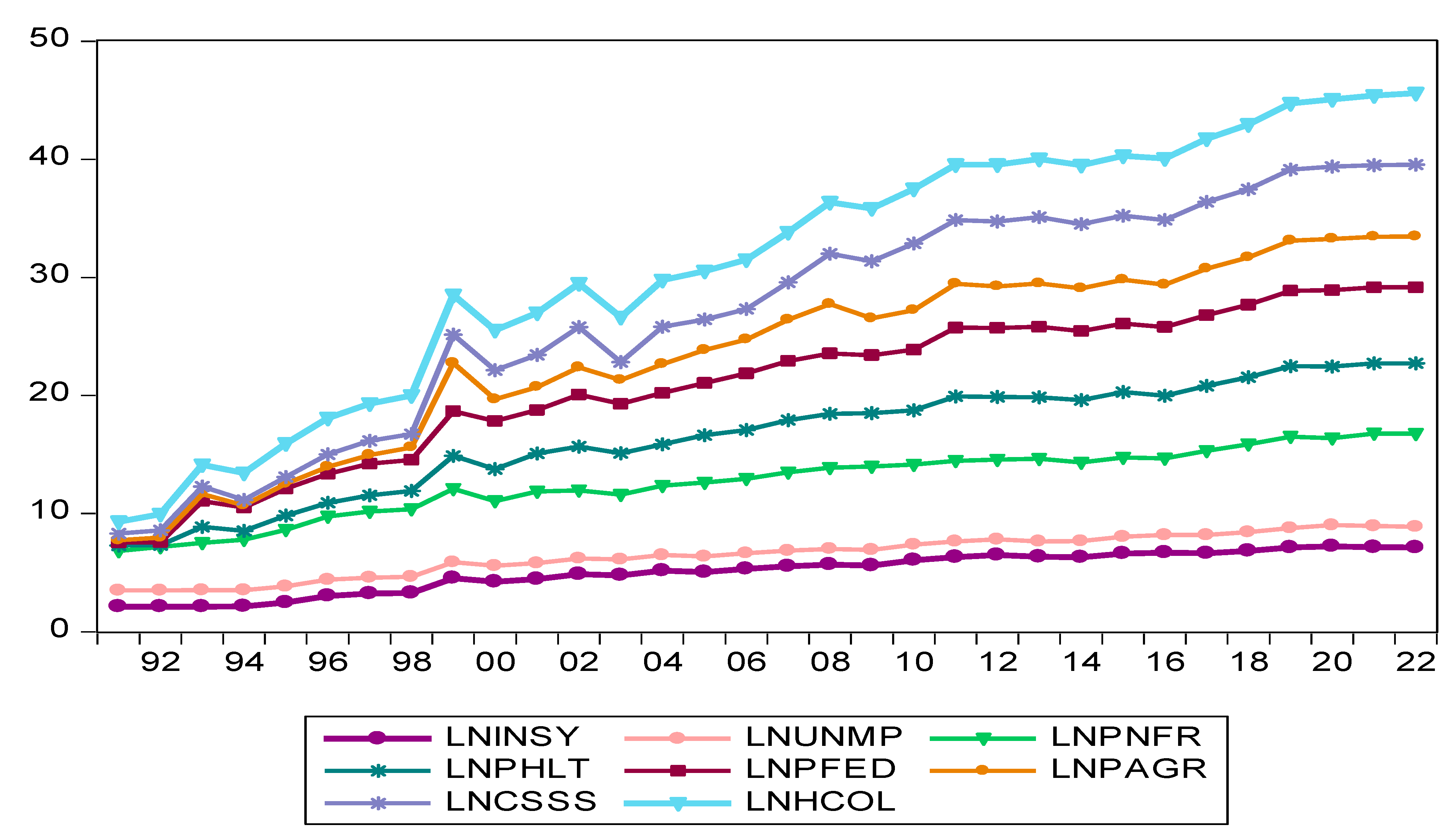

| Variable | Description | Data Measurement | Transformation Type | Data Collection Period | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insecurity | Measured in national currency (Naira) | Natural logarithm | 1991–2022 | CBN Statistical Bulletin https://www.cbn.gov.ng/documents/Statbulletin.asp (accessed on 14 June 2023) | |

| Unemployment Rate | Measured in national currency (Naira) | Natural logarithm | 1991–2022 | CBN Statistical Bulletin https://www.cbn.gov.ng/documents/Statbulletin.asp (accessed on 14 June 2023) | |

| Infrastructure | Measured in local currency (Naira) | Natural logarithm | 1991–2022 | CBN Statistical Bulletin https://www.cbn.gov.ng/documents/Statbulletin.asp (accessed on 14 June 2023) | |

| Healthcare facilities | Measured in domestic currency (Naira) | Natural logarithm | 1991–2022 | CBN Statistical Bulletin https://www.cbn.gov.ng/documents/Statbulletin.asp (accessed on th June 2023) | |

| Funding of Education | Measured in home currency (Naira) | Natural logarithm | 1991–2022 | CBN Statistical Bulletin https://www.cbn.gov.ng/documents/Statbulletin.asp (accessed on 14 June 2023) | |

| Agricultural Development | Measured in local currency (Naira) | Natural logarithm | 1991–2022 | CBN Statistical Bulletin https://www.cbn.gov.ng/documents/Statbulletin.asp (accessed on 14 June 2023) | |

| Community Social Services | Measured in domestic currency (Naira) | Natural logarithm | 1991–2022 | CBN Statistical Bulletin https://www.cbn.gov.ng/documents/Statbulletin.asp (accessed on 14 June 2023) | |

| High Cost of Living | Measured in national currency (Naira) | Natural logarithm | 1991–2022 | CBN Statistical Bulletin https://www.cbn.gov.ng/documents/Statbulletin.asp (accessed on 14 June 2023) |

| INSY | UNMP | PNFR | PHLT | PFED | PAGR | CSSS | HCOL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 5.08 | 1.42 | 6.17 | 3.78 | 4.42 | 2.67 | 3.55 | 4.07 |

| Median | 5.42 | 1.36 | 6.39 | 4.27 | 4.85 | 3.22 | 3.31 | 4.22 |

| Maximum | 7.22 | 1.79 | 7.87 | 6.05 | 6.47 | 4.34 | 6.11 | 6.04 |

| Minimum | 2.12 | 1.31 | 3.33 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.48 | 1.00 |

| Std. Dev. | 1.71 | 0.14 | 1.17 | 1.88 | 1.77 | 1.44 | 2.08 | 1.29 |

| Skewness | −0.53 | 1.66 | −0.77 | −0.54 | −0.83 | −0.56 | −0.17 | −0.60 |

| Kurtosis | 1.98 | 4.37 | 2.99 | 1.93 | 2.81 | 1.82 | 1.45 | 2.78 |

| Jarque-Bera | 2.85 | 17.2 | 3.19 | 3.06 | 3.69 | 3.49 | 3.34 | 2.01 |

| Probability | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.36 |

| Sum | 162 | 45.4 | 197 | 121 | 141 | 85.4 | 113 | 130 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. | 90.2 | 0.63 | 42.9 | 109 | 97.2 | 64.7 | 134 | 51.7 |

| Observations | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| VARIABLE | INSY | UNMP | PNFR | PHLT | PFED | PAGR | CSSS | HCOL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INSY | 1.00 | |||||||

| UNMP | 0.51 | 1.00 | ||||||

| PNFR | 0.74 | 0.50 | 1.00 | |||||

| PHLT | 0.79 | 0.49 | 0.73 | 1.00 | ||||

| PFED | 0.77 | 0.47 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 1.00 | |||

| PAGR | 0.75 | 0.46 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 1.00 | ||

| CSSS | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 1.00 | |

| HCOL | 0.77 | 0.57 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 1.00 |

| Variable | ADF T-Statistic | Critical Value @ 5% | p-Value | Order of Co-integration | PP T-Statistic | Critical Value @ 5% | p-Value | Order of Co-integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNINSY | −5.01 | −2.99 | 0.00 | I(0) | −7.26 | −2.96 | 0.00 | I(1) |

| LNUNMP | −3.52 | −2.99 | 0.02 | I(1) | −3.23 | −2.96 | 0.03 | I(1) |

| LNHCOL | −3.11 | −2.97 | 0.03 | I(1) | −3.27 | −2.96 | 0.02 | I(0) |

| LNPAGR | −4.07 | −2.99 | 0.00 | I(0) | −11.28 | −2.96 | 0.00 | I(1) |

| LNPNFR | 6.68 | −2.96 | 0.00 | I(1) | −6.61 | −2.96 | 0.00 | I(0) |

| LNPHLT | −4.89 | −2.99 | 0.00 | I(0) | −8.82 | −2.96 | 0.00 | I(1) |

| LNPFED | −4.46 | −2.98 | 0.00 | I(0) | −4.08 | −2.96 | 0.00 | I(0) |

| LNCSSS | −8.26 | −2.96 | 0.00 | I(1) | −8.18 | −2.96 | 0.00 | I(1) |

| F-Statistic | Significance | I0 Bound | I1 Bound |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6.02 | 10% | 2.03 | 3.13 |

| 5% | 2.32 | 3.50 | |

| 2.5% | 2.60 | 3.84 | |

| 1% | 2.96 | 4.26 |

| Lag | LogL | LR (Likelihood Ratio) | FPE (Final Predictor Error) | AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) | SC (Schwarz Information Criterion) | HQ (Hannan–Quinn Info Criterion) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 20.44 | NA | 0.026 | −0.829 | −0.455 | −0.709 |

| 1 | 20.72 | 0.402 * | 0.027 * | −0.782 * | −0.361 * | −0.647 * |

| 2 | 20.78 | 0.074 | 0.029 | −0.719 | −0.252 | −0.569 |

| Dependent Variable: LNINSY | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| C | 0.81 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.40 |

| LNINSY(−1) | 0.47 | 0.26 | 1.79 | 0.09 ** |

| LNCSSS(−1) | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.48 | 0.63 |

| LNHCOL(−1) | 0.68 | 0.32 | 2.12 | 0.05 *** |

| LNPAGR(−1) | −0.13 | 0.13 | −0.99 | 0.33 |

| LNPFED(−1) | −0.47 | 0.19 | −2.41 | 0.02 *** |

| LNPHLT(−1) | 0.48 | 0.21 | 2.31 | 0.03 *** |

| LNPNFR(−1) | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.99 | 0.33 |

| LNUNMP(−1) | −0.79 | 0.44 | −1.82 | 0.08 ** |

| Dependent Variable: D(LNINSY) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| C | 0.034002 | 0.080298 | 0.423444 | 0.6765 |

| D(LNINSY(−1)) | 0.375386 | 0.262375 | 1.430726 | 0.1679 |

| D(LNCSSS(−1)) | −0.043067 | 0.080737 | −0.533428 | 0.5996 |

| D(LNHCOL(−1)) | 0.803957 | 0.394329 | 2.038801 | 0.0549 ** |

| D(LNPAGR(−1)) | −0.117793 | 0.096009 | −1.226892 | 0.2341 |

| D(LNPFED(−1)) | −0.661963 | 0.160354 | −4.128144 | 0.0005 *** |

| D(LNPHLT(−1)) | 0.716182 | 0.183187 | 3.909560 | 0.0009 *** |

| D(LNPNFR(−1)) | −0.082304 | 0.170818 | −0.481823 | 0.6352 |

| D(LNUNMP(−1)) | −0.973583 | 1.163512 | −0.836762 | 0.4126 |

| ECM(−1) | −1.039294 | 0.279001 | −3.725053 | 0.0013 *** |

| F-statistic | 0.627 | Prob. F(2,18) | 0.545 |

| Obs*R-squared | 1.953 | Prob. Chi-Square(2) | 0.376 |

| F-statistic | 1.864 | Prob. F(9,20) | 0.118 |

| Obs*R-squared | 13.68 | Prob. Chi-Square(9) | 0.134 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omodero, C.O. Social Factors Associated with Insecurity in Nigerian Society. Societies 2024, 14, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14060074

Omodero CO. Social Factors Associated with Insecurity in Nigerian Society. Societies. 2024; 14(6):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14060074

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmodero, Cordelia Onyinyechi. 2024. "Social Factors Associated with Insecurity in Nigerian Society" Societies 14, no. 6: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14060074

APA StyleOmodero, C. O. (2024). Social Factors Associated with Insecurity in Nigerian Society. Societies, 14(6), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14060074