1. Introduction

Researching playfully? Playing as a research method? In the first moment, this sounds contradicting, but in recent years more and more methods have incorporated creative or playful elements (e.g., role games) to enrich qualitative research outputs [

1,

2]. Helen Kara [

3] termed the beginning of the 21st century “a dynamic and exciting time for research methods” [

3] (p. 3), softening methodological boundaries and opening new margins for creativity in research [

4,

5].

Researching vulnerable people requires an openness towards methodological modifications and innovations as the diversity of this particular group calls for high methodological flexibility, especially with regard to accessing and recruiting them, as well as the collection of data [

6]. People in vulnerable conditions are often suffering from structural disadvantages (e.g., with regard to communication and/or mobility) and individual constraints (e.g., cognitive and/or language skills) limiting or even impeding their opportunities to participate in research projects [

6,

7,

8].

Along with Jo Aldridge and other advocates of creative and participatory research (e.g., David Gauntlett, Helen Kara), we share the position that relying solely on established methods of social inquiry (such as interviews, group discussions etc.) [

9,

10] is neither inviting to vulnerable people to participate in research, nor is it appropriate with regard to the expected outcomes. Conducting research with established methods runs the risk of reproducing inherent power structures [

11], which impede open communication [

8], and being reductive by fixing and limiting meaning [

3] (p. 8). Especially with regard to vulnerable groups, there should be a higher interest in unveiling their specific stocks of knowledge and experiences—always taking into consideration the individual abilities of “abstract reasoning, memory performance and verbal contribution” [

6] (p. 3). This applies particularly if we follow the idea of transformative research, which is not primarily focused on the production of systems knowledge [

12], but rather on the production of target and transformation knowledge, which empowers people, and especially vulnerable groups, to develop visions and become co-creators of social change themselves.

In this article, we argue that LEGO® Serious Play® addresses the aforementioned shortcomings of traditional research methods by dissolving power structures, opening minds by hands-on experiences and offering space for narrations and visions. Although LEGO® Serious Play® seems to be a low-threshold method due to its playful character, there are some limitations that should be taken into consideration before working with it in the field.

2. LEGO® Serious Play® in Practice and Research

LEGO

® Serious Play

® is an innovative tool to develop joint ideas, visions, and scenarios and to reflect on them. It can be perceived as a method for change management using LEGO

® bricks as a medium or common language and play as an “enabler”, but “both the LEGO

® and the Play serve the ultimate purpose of a Serious outcome” [

13] (p. 4). However, we argue that by “using game elements in non-game contexts” [

14] (p. 2) LEGO

® Serious Play

® fits in recent discourses on gamification [

14,

15,

16], but it cannot be subsumed in the field of serious games, which generally are fully fledged games and—although pursuing a serious purpose—always have an inherent entertainment dimension [

17]. LEGO

® Serious Play

® rather capitalizes on the experiences arising from play situations, such as captivation, exploration and expression, and fellowship and humor [

18]. The method is based on the creation of symbolic representations, which emanate in a non-judgmental setting of play [

19] (p. 134) where all participants and all ideas are appreciated equally [

11].

Initially developed as an innovative tool to make strategic business development processes in the LEGO

® company itself more effective, LEGO

® Serious Play

® has meanwhile become an established method to improve the consulting purposes in enterprises throughout the world [

20]. In recent times, it has also been used for other purposes, such as research on tourism [

21,

22], intercultural studies [

23], higher education [

11], social care [

24], technology use in refugee camps [

25], and teaching (for example, with international nursing students [

26,

27]). In general, LEGO

® Serious Play

® works in all contexts that are shaped by communication and social interaction [

13], and thus also in research.

Although in the last two decades plenty of work was published on LEGO

® Serious Play

®, most of these publications are dedicated to concrete applications—especially in business and organizational contexts—while others are rather focussing on the theoretical and conceptual aspects [

1]. In view of the potential conceptual intersections between LEGO

® Serious Play

® and qualitative research methods (e.g., the relevance of storytelling, narrations, and visual communication [

28]), it is interesting to assert that the potential of LEGO

® Serious Play

® as an instrument for data collection in qualitative research has not been reflected comprehensively until now.

We argue that the application of LEGO

® Serious Play

® blends into the debate on methodological innovations, claimed amongst others by supporters of the non-representational theory [

29] and advocates of co-creative research [

3,

30]). Already in the early 2000s, Gauntlett [

19] pleaded in his book “Creative Explorations” for leaving the worn-out paths of technocratic research towards approaches “which allow participants to spend time applying their playful or creative attention to the act of making something symbolic or metaphorical, and the reflecting on it” [

19] (p. 3). He argued that conventional qualitative research is not able to sufficiently uncover “the unconscious” which inevitably leads to the limited explanatory power of the obtained data. Furthermore, Bettmann and Roslon [

31] appealed to be more creative in the development of research designs by methodological adjustments to individual research contexts. With regard to migration studies, Aldridge pleads to develop and apply “bespoke“ methods [

6] (p. 18) that are highly reflexive concerning the individual contexts of migrants and which are based on narrative techniques to explicitly focus on the migrants as the narrators of “their” stories giving them a voice to overcome a “culture of silence” [

32] (p. 214). Thus, experiences and views can be shared and reflected on in a new way that cannot be caught by verbal and conventional research methods [

33].

In addition, Law and Urry [

34] asserted that the classic methods of the social sciences are not any more suitable to capture the complexity of the present social world. A change of perspectives is needed in qualitative research to meet the requirements of new social complexities [

30]. These complexities require not only methodological adjustments, but a revision of (social) science in general [

19,

35]. Research should become more meaningful and relevant for society by unfolding its transformative character. Following this idea, research should not only produce analytical knowledge about structures and processes (systems knowledge), but knowledge to design and organize change (target knowledge and transformation knowledge) [

12].

In this sense, LEGO

® Serious Play

® can serve as a tool for the co-production of knowledge. It offers the opportunity to capture momentum, to stick to the present and to venture into being speculative, but not to be wedded to the past. Used as a tool for development purposes, it lays the groundwork for ambiguity and the evolution of the status quo [

36]. By connecting the brain and hands and expressing thoughts by building something, LEGO

® Serious Play

® helps to make the unconscious visible and traceable—either as systems knowledge or even as target or transformation knowledge. The following article will therefore try to outline these particular intersections and disclose the possibilities and limitations of LEGO

® Serious Play

® for qualitative research purposes.

3. The LEGO® Serious Play® Experience

LEGO

® Serious Play

® is a game-based method that uses the merits of play for serious purposes. Game-based methods create interrelations between playful self-fulfillments and social realities which Heimlich calls “central moments of reality experience” [

37] (p. 18).

Basically, LEGO

® Serious Play

® builds on the principal considerations of play theories, imagination theories, and constructionism theory [

38]. Framed by the assumption that play always serves a certain purpose and is “limited in time and space, structured by rules, conventions, or agreements among the players, uncoerced by authority figures, and drawing on elements of fantasy and creative imagination” ([

39], as cited in [

19] p. 134), participants in LEGO

® Serious Play

® processes are animated to go beyond the visible world by using metaphorical or symbolic expressions for their thoughts. By building individual three-dimensional models with LEGO

® bricks (in response to specific facilitator’s questions) and the subsequent explanation as storytelling, participants are driven to use metaphors in order to transform abstract or intangible concepts which they have in their minds into concrete and generally comprehensible ideas and artifacts.

The strictly focused hands-on-the-model concentration during the building and storytelling action displaces the participants into a state of flow, which is characterized by a high level of involvement, concentration, and altered perception of time. The Dutch educational technologist Wim Westera summarizes the effect of being in a flow as follows: “If such states were achieved in schools, the students would not want to leave the school by the end of the day, but continue their work. They would not even hear the school bell ring” [

40] (p. 1). Mihaly Czikszentmihaly [

41] is seen as the founder of the flow theory, identifying the impact that flow experiences have on creativity. Together with Moneta, Czikszentmihaly detects three motivational systems, so-called teleonomies, represented by the flow theory: the genetic teleonomy (like eating), the cultural teleonomy (e.g., social and/or economic success), and the teleonomy of the self as a basis for individual decision-making. [

42] This last teleonomy is the one triggering the flow in LEGO

® Serious Play

® and is the basis of the LEGO

® Serious Play

® experience. Moneta and Czikszentmihaly [

42] further distinguished four dimensions of the flow: (1) concentration, (2) wish to perform the activity, (3) involvement, and (4) happiness. These dimensions of flow are also important for the (positive) experience and the results of a LEGO

® Serious Play

® workshop. Empirical evidence according to Primus and Sonnenburg [

43] shows that in LEGO

® Serious Play

® the group flow of all participants is always associated with the flow of each individual participant. In their study on the creative outputs of LEGO

® Serious Play

®, Zenk et al. [

44] have shown that it is also the state of flow which dissolves existing hierarchies within groups.

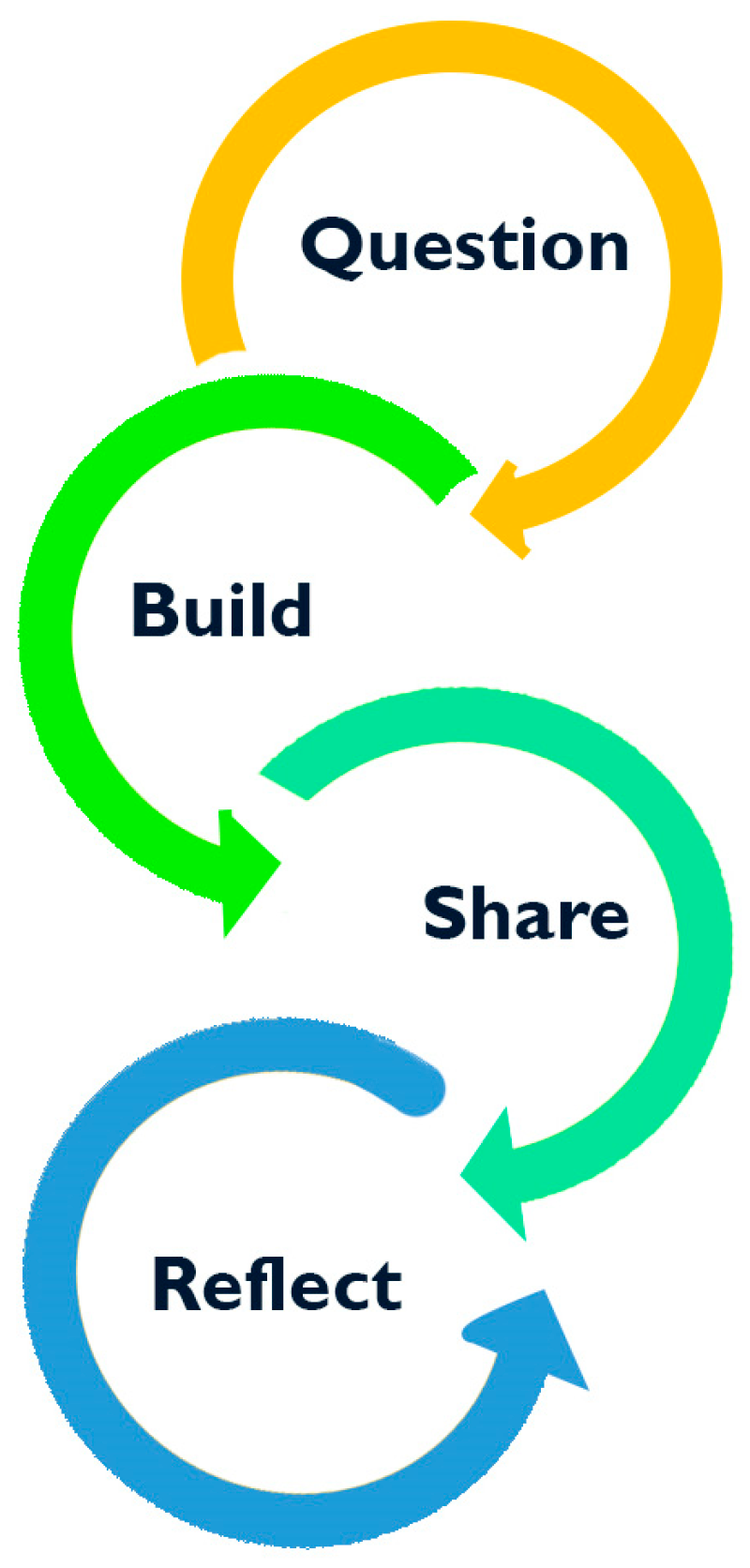

The flow is elicited by the recurrent process in each sequence of a LEGO

® Serious Play

® workshop (

Figure 1): Every sequence starts with a specific question that triggers the individual thinking processes. The answer to this question is built with bricks within a very limited time slot (just a few minutes). This timebox is often perceived as being stressful; however, it is necessary to put the participants into a state of flow. After the building has been finished, every participant starts sharing his/her thoughts expressed in the model. Reflecting on the story with the whole group offers the possibility for further inquiries and capturing the message behind it.

The combination of construction and storytelling offers opportunities to “express ideas or thoughts, which might not otherwise be able to put into words” [

19] (p. 152). However, storytelling is more than just a reproduction of facts, it also expresses emotions, moods, reflections, and interpretations [

45] (p. 30). At this point, it intersects with the considerations of imagination theory, which not only reveal a status quo of the world, but “enables us to make sense of it and to see new possibilities and opportunities” (descriptive imagination), or “allows us to see what isn’t there” (creative imagination), or even “negates, defames, contradicts and even destroys the sense of progress that comes from descriptions and creativity” [

39] (p. 14). It does not surprise that storytelling and construction constitute the most important assets in LEGO

® Serious Play

® processes. They are encouraging imaginations and creativity to unveil tacit and implicit stocks of knowledge, experiences, and ideas, and thus, create a participatory and immersive experience. Malafouris calls this nexus of “thinking through and working with materials” ‘creative thinging’ [

46] (p. 145).

The results created in LEGO® Serious Play® processes have explanatory as well as transformative power as they build upon individual knowledge and experiences on the one side, and on group consent on the other. Visions developed within LEGO® Serious Play® processes, for example, are characterized by a high degree of support from all group members because everyone identifies himself/herself with the ideas incorporated in the vision. This experience enhances self-efficacy and especially empowers vulnerable people who suffer from being overlooked, ignored, or marginalized.

The synthesis of all the facets of serious play—playful self-fulfillment, imagination and creativity, flow experience, and social interaction– shape the particular LEGO

® Serious Play

® experience, which leads to a multitude of insights and ideas, a high level of commitment with regard to the perspective results and decisions, and last but not least, to a higher degree of social bonding within the team. Or, as Fearne puts it, “LEGO

® Serious Play

® is a different way to think and a different way to have conversation” [

13] (p. 30).

4. Researching Vulnerable Groups with LEGO® Serious Play®

Compared to other methods in qualitative research, like group discussions or focus groups, LEGO

® Serious Play

® is especially distinctive regarding the level of participation and the expected outcomes. As Zenk et al. [

44] have shown, LEGO

® Serious Play

® processes are highly inclusive as all participants are actively involved in sharing their knowledge, opinions, and ideas. Based on the assumption that “the answers are ‘already in the room’, [LEGO

® Serious Play

®] invites participants to ‘think with their hands’ to build their understandings. Every member of the team participates, and everyone has a voice” [

47].

While McGonigal [

48] pleads to reconsider the negative connotations widely associated with games as being “timewasters”, this article argues that game-based approaches like LEGO

® Serious Play

® can be a proper supplement for qualitative research, especially with regard to vulnerable or hard-to-access groups.

Vulnerabilities can be as diverse as the understanding of what it is. In a very broad sense, people can define themselves as being vulnerable or not and if so, which vulnerabilities they perceive. In the literature, the definitions range from the individual level to the policy level. In the field of migration, Brown et al. [

49] even call it a “buzzword”, which is self-explanatory. Vulnerabilities can be the “consequence of a particular situation or as the product of a structural system” [

50,

51,

52]. Vulnerabilities have been seen in their embeddedness as well as in context (history, life circle, institutional, and geopolitical) and very often in combination with different, multi-layered, and dynamic factors [

50]. Moreover, vulnerabilities are temporal. They can be perceived from the past, present, or also from the images of their future, which are influenced by the past and present and play an especially important role in the age of transition into adulthood [

50,

53]. The work of Gilodi et al. [

53] defines four types of vulnerabilities: innate vulnerability (natural condition of a person/group [

43]), situational vulnerability (e.g., experiences, living situation, and exposed situation), experiential vulnerability (individual interpretation of situations and/or conditions of being vulnerable) [

54], and structural vulnerability [

55,

56]. Moreover, the intersectionality and individual interpretations as well as subjectivity of/towards different vulnerabilities increases the complexity of the concept. In the context of migration issues, vulnerabilities can be perceived in very different ways, but concretely cover difficulties with language learning, as well as cultural (e.g., racist, religious), educational (e.g., non-recognition of qualification), professional, subsistence-related (e.g., housing), bureaucratic, safety-related, psychological (e.g., identity conflicts), and gender-related difficulties [

57]. Misusing the concept of vulnerability or instrumentalising it can also lead to discrimination, stigmatization, patronization, disempowerment, oppression, fostering through social control, exclusion, and labelling [

53].

To reduce the focus on vulnerabilities or even to foster existing ones, a LEGO

® Serious Play

® workshop should begin with finding a common language ground and a way to communicate. An important requirement for working with vulnerable groups is to find common understandings by explaining and expressing the ideas built with LEGO

® bricks. Vulnerable groups need to feel that they are in a safe space and that whatever they will be built is valued. With regard to the diversity of vulnerabilities and the related risks of harm, LEGO

® Serious Play

® should be carefully applied, after serious consideration, as a method for researching vulnerable groups. Especially, the process of storytelling can have undesirable effects, such as triggering traumatic experiences. This makes it impossible to define exactly for whom this method is applicable and for whom it is not. Thus, ethical requirements are to be thought through even more before organizing a LEGO

® Serious Play

® workshop. The aim of ethical considerations is not just to prevent vulnerable persons from further risks of harm, but also to avoid an aggravation of their existing vulnerabilities [

6]. For art-based events and participatory research, Pietrusińska, Winogrodzka and Trąbka [

58,

59] recommend to not only include “procedural ethics” (like ethical approval of an institution), but “ethics in practice” with a deeper ethical self-reflection that leads to improved empowerment and decreases patronization, exclusion or disempowerment. Which groups might be able to work together? Which age groups, which migrant background, which vulnerabilities, etc.? The more diverse the group is, the better the results will be, but the more the facilitator must make sure that each participant is a part of the building process. Depending on the felt vulnerabilities (less language skills might be one), a single person or a smaller group might dominate the others as they feel more comfortable speaking the language or they are more self-convinced. Therefore, it is also important that the vulnerable participants do not experience any of the potential misuse of labelling them as a vulnerable group, or by discriminating, stigmatizing, patronizing, disempowering, oppressing, fostering through social control, excluding, or by putting the label that is used for defining the group into the forefront. In fact, LEGO

® Serious Play

® is a method that through the playful approach tries to overcome all these challenges by empowering each participant through the individual and joint components of the method. The facilitator, as well as the participants, need to be open to the opinions and ideas of others, empathetic, committed, and willing to leave their comfort zone [

58]. Especially for arts-based and creative research methods ethical considerations should also include the recording, handling, and processing of visual material that will be produced within the process of documentation [

60]. However, facilitators of workshops should already have potential risks in mind at the stage of preparing the workshop concept. Finally, not all risks are fully predictable. However, facilitators should be able to anticipate potential risks, and thus, be prepared to intervene properly. For facilitators this can be very challenging, as the worst case of intervention can mean offering some kind of psychological support.

5. Assets and Drawbacks of LEGO® Serious Play®

As outlined in the introduction of this article, the different application fields of LEGO® Serious Play® are quite well documented. However, its usability within research contexts has been touched upon very rarely, by David Gauntlett at the most. This blind spot notwithstanding, this article argues that due to its innovative and inspiring nature LEGO® Serious Play® offers definite possibilities to be applied in research contexts. It is not self-explanatory to assign it to the range of qualitative research methods as it does not correspond to the basic criteria of quantitative research, such as the level of standardization or the intention of the research. Basically, LEGO® Serious Play® is used in a group context. Hence, all the empirical evidence about this method is based on group experiences. However, in principle, it can also partly be used for individual investigation.

The applicability of LEGO® Serious Play® for qualitative research will be discussed along three levels: the process, the methodology, and the target group.

5.1. Process

Research does not start with the gathering of data, but much earlier with a formulation of one (or more) research question(s) and the modelling of the research design. Already at this early point of the research process, the main asset of LEGO

® Serious Play

® is the ability to generate a wide range of ideas that facilitates the sketching of the field of investigation and the delimitation of the crucial research question(s). Typically, at this stage of developing a research design, language-based methods (e.g., brainstorming and mind mapping) are applied. It is not to question their usability, but “language is not necessarily the best way to explain how a number of elements coexist and are linked together” [

19] (p. 183).

Building individual identities as representational or symbolic objects for abstract concepts (e.g., “What means poverty to me?”) unveils more than just semantics. It also includes interpretations, reflections, experiences, and assessments, which in the end are more meaningful than just keywords. Metaphors are the building of a bridge between the thoughts and bricks as they downsize abstract or intangible concepts to comprehensible images. The factor of “time” also becomes relevant here as the short time slots for reflection, which are inherent in the given time boxes for building, may enhance the quality of the data [

19].

This is also true for the process of data gathering. Herein, LEGO

® Serious Play

® may be a suitable alternative for narration-based methods, such as interviews. Gauntlett points, in this context, to the inexperience many people have in transferring their thoughts about personal or social matters into the kind of talk that you would share with a researcher” [

19] (p. 182). Under certain circumstances, even an integration of LEGO

® Serious Play

® into a qualitative interview design is imaginable, e.g., as a narration stimulus in biographical narrative interviews. Furthermore, it can be integrated into group discussions to open the minds for the process. As group discussions often run the risk of being dominated by the opinions of just a few [

61], LEGO

® Serious Play

® gives a voice to everyone and thus offers the opportunity to integrate all participants [

44].

For the process of analysis, it is crucial to consider all steps of the LEGO® Serious Play® process. When comparing different groups, it is important that the concept of the workshop is identical to make the results comparable even though LEGO® Serious Play® is always dependent on the individual flows and personal biographies of the persons participating and of the interaction and understanding between the different participants in a workshop.

5.2. Methodology

LEGO

® Serious Play

® processes consist of different stages, which can be passed through either separately or combined [

40,

48]. The level of the “individual identity” represents individual thoughts and ideas while “joint identities” express a common sense or joint ideas of a group. The third level, the so-called landscape, introduces the possible effects of particular elements in the ecosystem on the joint model, and thus contributes to a higher awareness of the influences and possible interdependencies in the given system. Individual identities reveal insights into subjectivities; like other qualitative methods of social inquiry, they help to produce knowledge about systems, whereas joint identities and landscapes are meaningful with regard to generating targets and visions or transformative knowledge. Depending on the scientific objectives, a workshop design can only foresee the level of building of an individual identity or proceed with joint identities and landscapes.

As has been mentioned above, LEGO

® Serious Play

® is predominantly used in a group context. Due to its playful character, McCusker [

11] sees a large potential in this method to especially be applied in heterogeneous groups. However, LEGO

® Serious Play

® works best with a manageable number of participants as every participant has an opportunity for storytelling. Depending on the number of participants and levels realised in a workshop, LEGO

® Serious Play

® can be very time-consuming [

11]. A particular challenge for the facilitator is to keep up the attention and concentration of all participants to follow the stories that serve as sources for inspiration during the course of the process. Furthermore, McCusker [

11] and Wengel [

21] refer to the high costs related to this method: LEGO

® itself sells customised kits for different workshop levels, ranging from small “exploration kits” and larger “starter kits” for individual models, up to “identity and landscape sets” for joint models. Their usage is not mandatory, but favourable [

11]. However, Wengel [

21] shows that it is also possible to work with self-made LEGO

® kits. With regard to the diversity aspects which are of high relevance, for instance in migration studies, this is even strongly recommended as the customised sets do not consider different skin colours. Closely connected to the question of working material availability is the question of its bulkiness [

21]: LEGO

® Serious Play

® workshops require large rooms with large tables (

Figure 2a) offering enough space for storing the bricks as well as building (and presenting) the models (

Figure 2b). Working with LEGO

® Serious Play

® definitely requires sound preparation, not only from a conceptional perspective, but also with regard to organisational aspects.

Another potential shortcoming, which has to be mentioned in this context, is the documentation of results, which appears to be rather complex as is true for many visual methods. The moderators are fully absorbed by facilitating the workshop and flow, which prevents them from making any type of documentation. Wengel [

21] advises to strictly separate the roles of facilitators, also with regard to their involvement as being participants. As there is neither a mandatory instruction nor a scientifically validated concept for the documentation of LEGO

® Serious Play

® processes, it is highly recommended to use videography in order to capture all visual and verbal contributions. However, it always has to be taken into consideration that recordings are also filtered as they are not capable of taping everything, for example the atmospheres within a group, or the flow experience of each individual [

30].

5.3. Target Group

The inclusive nature of LEGO

® Serious Play

® has already been mentioned several times before. Basically, LEGO

® Serious Play

® has the potential “to establish dialogue and break social and cultural boundaries” [

62] (p. 389) as its playful character and the fundamental appreciation of diverse opinions appear motivating and inspiring to different target groups. This makes it especially valuable for researching vulnerable groups, e.g., migrants, but also people with learning disabilities, or persons whose vulnerabilities have arisen from sudden changes in life circumstances, such as the loss of employment or income.

Elementary preconditions for successful work with LEGO

® Serious Play

® are (1.) a certain openness towards the “tool” LEGO bricks and (2.) a certain level of language ability. Experiences with different target groups show that in some cases people are sceptical [

11,

21] or do not feel comfortable with the construction process. They already express some kind of resistance in the skills building phase, which serves as a means to become familiar with the material and the method. In this case, the workshop facilitator should try to motivate warily, but without exerting pressure. The possibility of leaving the process should always be given, as in other research methods. The second precondition, the language ability, refers to a lesser extent to the faculty of speech, but rather to linguistic proficiency. Especially when researching migrants using LEGO

® Serious Play

® the linguistic proficiency may be an obstacle as a low level of language skill reduces the potential of storytelling. This can become even more challenging when groups consist of people with different languages and translation becomes impossible.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to disclose the possibilities and limitations of LEGO

® Serious Play

® for qualitative research purposes, especially with regard to vulnerable groups. We have shown that LEGO

® Serious Play

® can definitely be used as methodological enrichment particularly for participatory research [

19,

34], and thus, also for the generation of transformative knowledge [

12]. It fills a methodological gap that has been discussed in social research for more than two decades. However, its utilization should always be well-reflected and adapted to the specific research context as it is definitely not a one-fits-all solution.

Compared to other methods in qualitative research, LEGO® Serious Play® is especially distinctive regarding the level of participation and the expected outcomes. As all participants are actively involved in sharing their knowledge, opinions and ideas in a creative manner, LEGO® Serious Play® processes are highly inclusive. Through its playful character, LEGO® Serious Play® is particularly attractive for groups, which are hard to access with conventional research methods (e.g., youth, migrants).

However, LEGO

® Serious Play

® processes can only be successful if the participants are able to open themselves towards this special method. Then, it unveils its capacity to give deep insights into interpretations, reflections, experiences, and assessments, which in the end are more meaningful than just keywords documented on a sheet of paper. However, it always has to be considered that now everyone can open himself or herself towards this method. Some might perceive this playful approach as childish, while others simply cannot overcome a mental “barrier” to express their ideas by building with bricks. Experiences from different workshops show that people can be really blocked when being invited to start building their models. In these cases, McCusker [

11] recommends starting with skills buildings as easy icebreakers for reluctant participants.

Hence, the application of LEGO® Serious Play® requires comprehensive considerations with regard to the addressed target groups, organizational questions, and also ethical issues. This becomes especially important with regard to language skills which are of basic importance for the storytelling, and consequently, for the successful utilization of LEGO® Serious Play®. Interestingly, the participants do not have to be experienced with LEGO®, which often is perceived as a necessary prerequisite by the participants of the workshops. However, observations from workshops conducted within the H2020 project also show that people without experience get into the flow of “thinging”, expressing their thoughts metaphorically with models of bricks. Another point for consideration that can be of tremendous relevance, especially when working with vulnerable groups, refers to ethical issues. The strength of LEGO® Serious Play® to open minds playfully, and thus, to unveil a broader range of information can bear the risk of unintentionally triggering certain, sometimes traumatic, experiences. Therefore, it is important to decide at an early stage of the research process if LEGO® Serious Play® is the appropriate method for investigating the chosen group, and if so, what provisions have to be made to minimize the risks of harm and to intervene in case of undesired reactions.

Finally, the question of documentation also has to be considered as this can be perceived as real pain point of the method for valid and reliable research. As LEGO® Serious Play® is highly interactive when used in a group context, the documentation of results is very challenging because all phases (including the warm-up and all the steps of individual modelling) and all elements of a session (e.g., description of models, storytelling, and reflections) should be recorded properly to minimize the loss of information.

All aspects considered, working with LEGO® Serious Play® requires—as with all methods in quantitative and qualitative research—a sophisticated and thorough preparation considering different contingencies, which might affect the process of inquiry. Then, it can unfold its potential of being a suitable and serious, as well as innovative, instrument for qualitative research, which is especially valuable for the generation of knowledge serving as basis for social change.