Measuring the Unmeasurable: Decomposing Multidimensional Rural Poverty and Promoting Economic Development in the Poorest Region of Luzon, Philippines

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Anatomy of Poverty and Its Multidimensionality

1.2. Rural Poverty

1.3. Measuring the Unmeasurable through Data Analytics and Econometrics

1.4. Purpose of the Present Study

2. Related Work

2.1. Examining Poverty and Its Causes

2.2. Global Poverty and Macroeconomic Calculations

2.3. The Sustainable Development Goals and Statistics of Poverty

2.4. Combating Poverty

2.5. Theoretical Frameworks

Rowntree’s Minority Group Theory

2.6. The Capability Approach of Amartya Sen

3. Method Used

3.1. Sample and Locale of Study

3.2. Sources of Data

3.3. Design

β6WAS_Water + β7WASF_Toilet + β8TNOHH_Members + β9CO_Typhoon + β10CO_Flood +

β11CO_Drought + β12CO_VolEruption + β13CO_LMSlide + β14DR_Prepared + β15CNA_Elem +

β16CNA_JunHS + β17CNA_SenHS + β18LF_Unmployed + β19Vic_Crime + βni + μ

β6WAS_Water + β7WASF_Toilet + β8TNOHH_Members + β9CO_Typhoon + β10CO_Flood +

β11CO_Drought + β12CO_VolEruption + β13CO_LMSlide + β14DR_Prepared + β15CNA_Elem +

β16CNA_JunHS + β17CNA_SenHS + β18LF_Unmployed + β19Vic_Crime + βni + μ

4. Results and Discussion

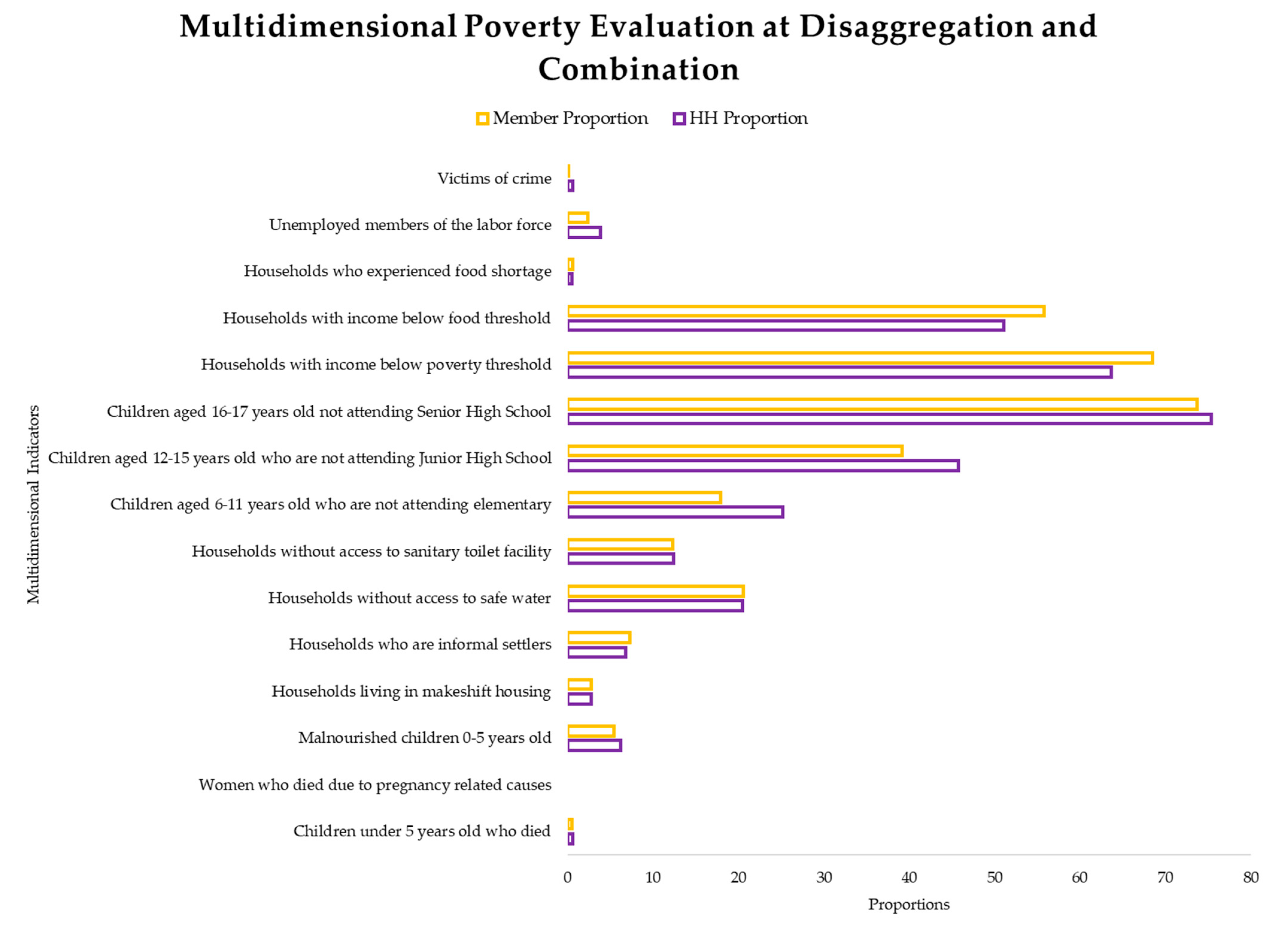

4.1. Multidimensional Poverty Profile

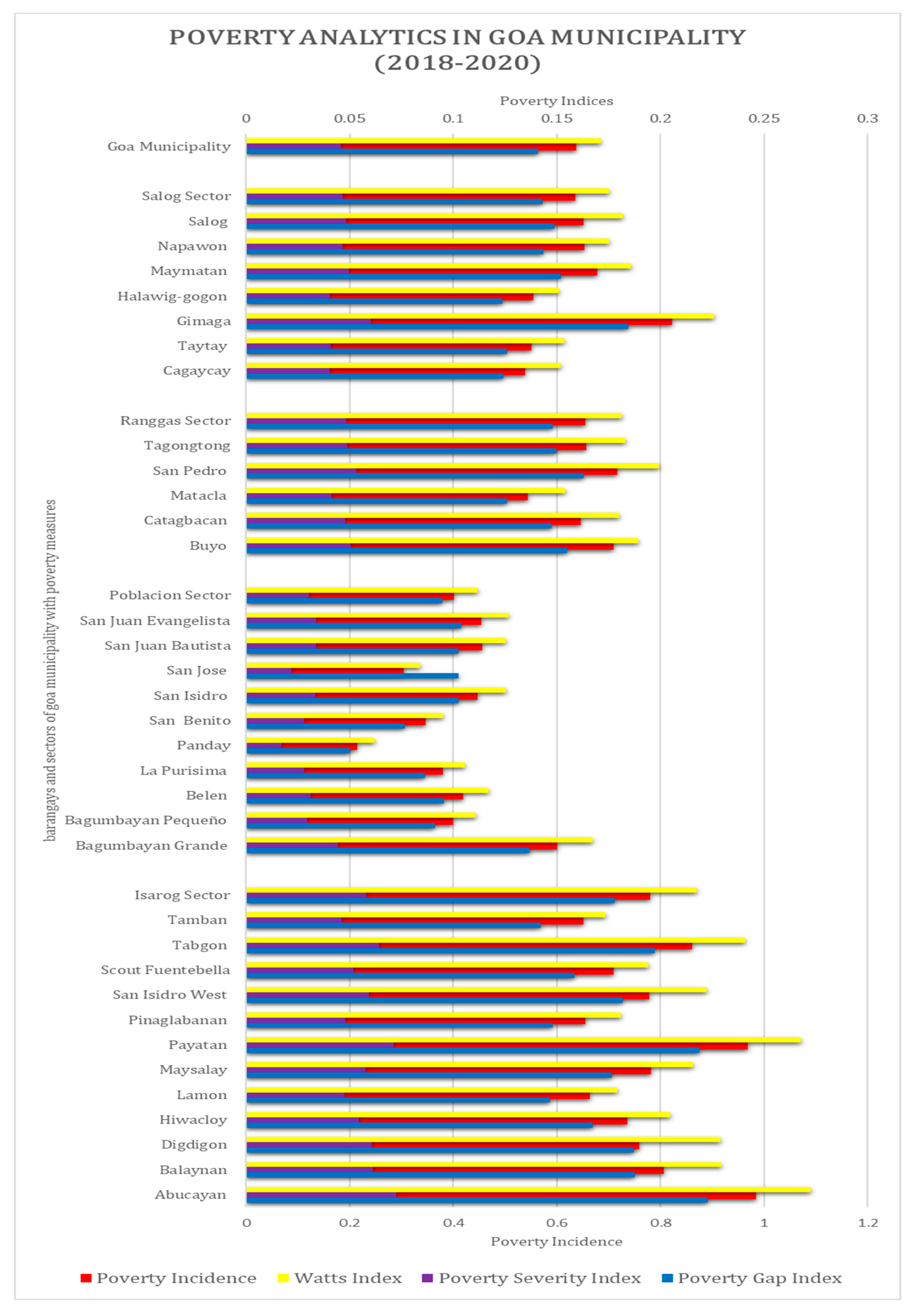

4.2. Multi-Sectoral Poverty Analysis

4.3. Extent of Poverty

4.4. Characterization of Health Dynamics

4.5. Calamity and Disaster Risk Preparedness

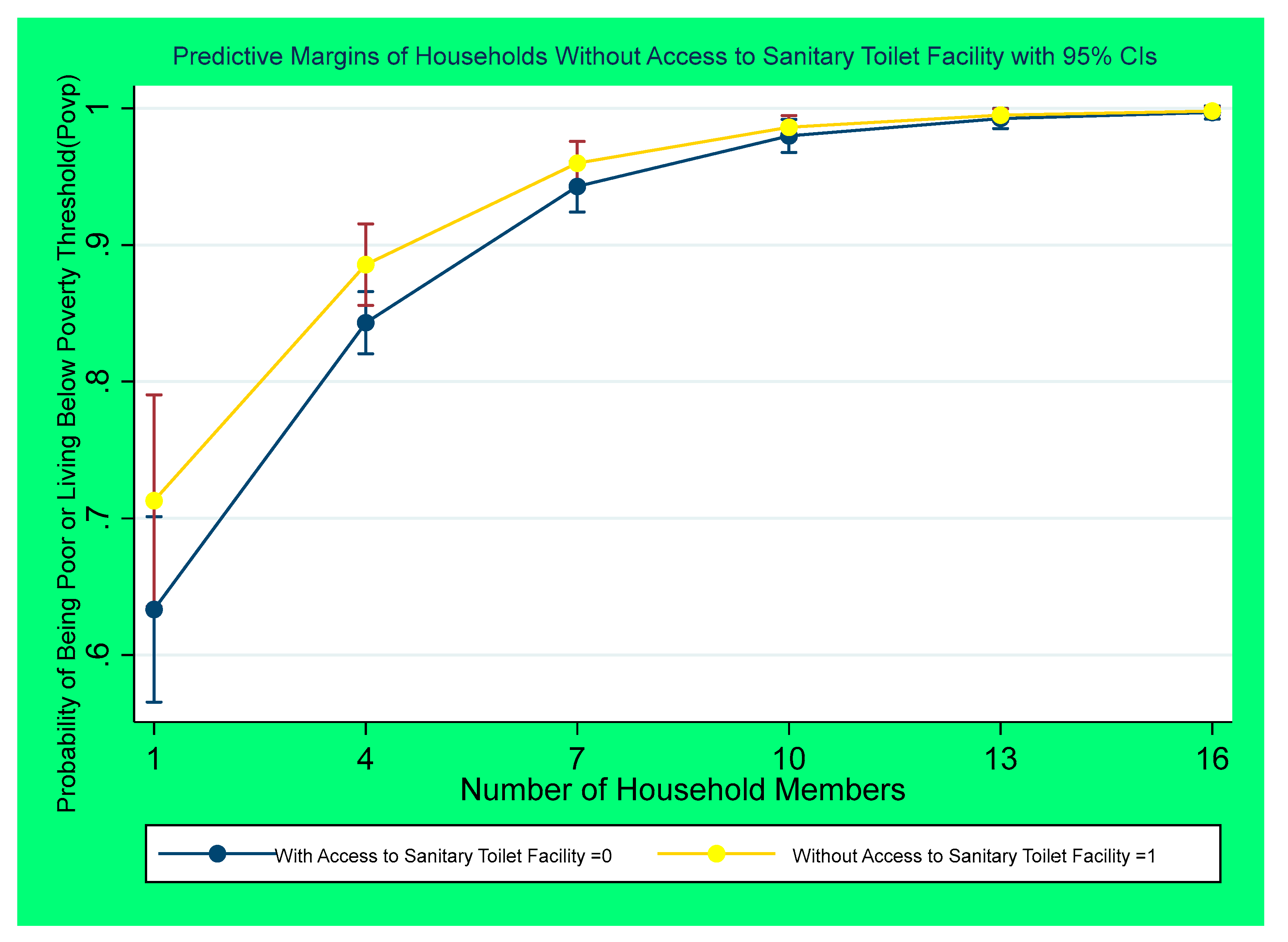

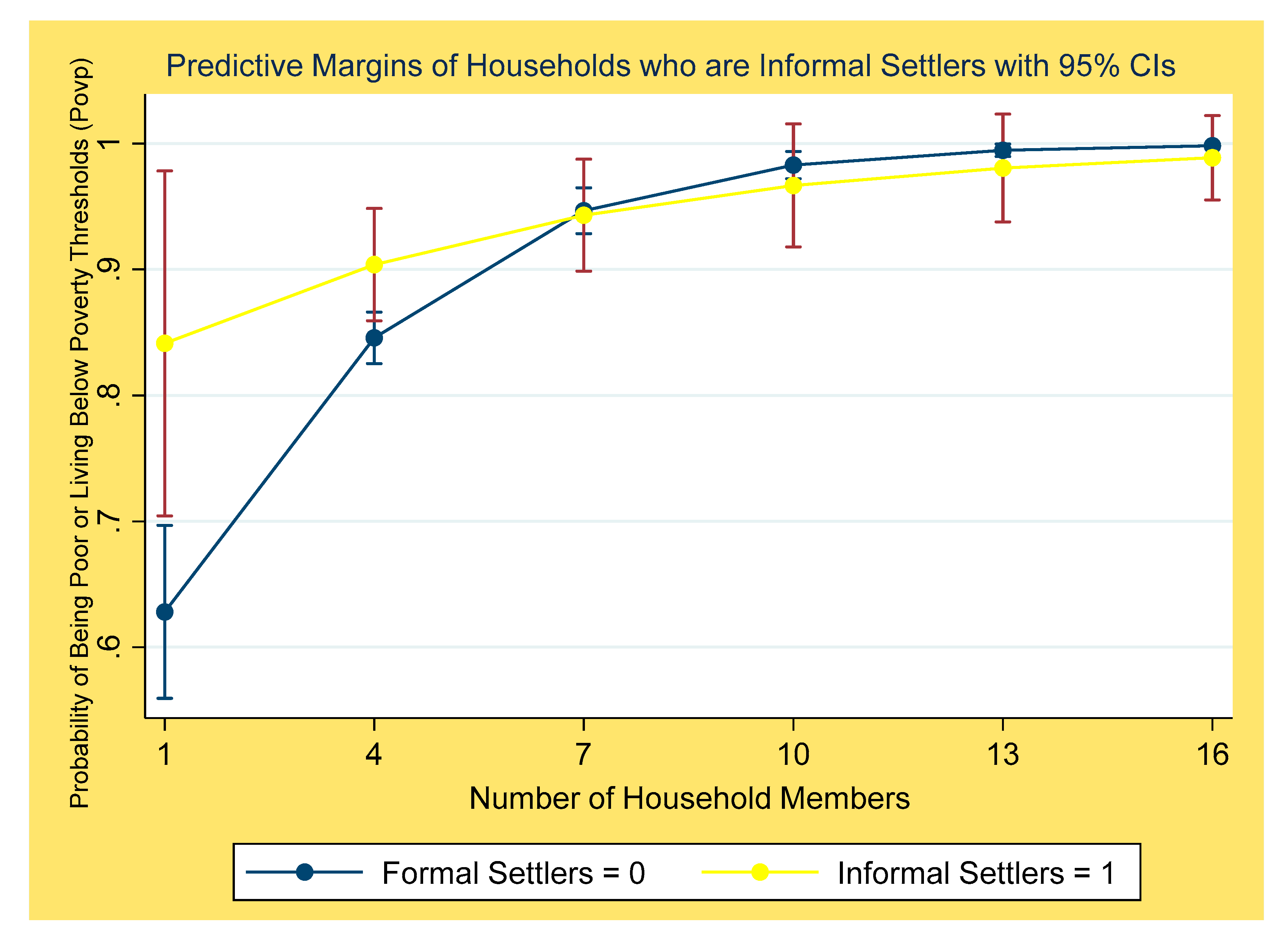

Predictive Analytics and Advanced Econometric Modeling

4.6. Novelty of the Study and Its Contributions to the Rural Community

4.7. Prescriptive Analytics for Economic Policies and Economic Development Infrastructure

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haughton, J.; Khandker, S.R. Handbook on Poverty and Inequality; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Abhijit Banejee, V.; Duflo, E. Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 303. ISBN 978-1-58648-798-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Conceptualizing and Measuring Poverty. Poverty and Inequality; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom (1999). The Globalization and Development Reader: Perspectives on Development and Global Change; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; p. 525. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Issues in the Measurement of Poverty; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1981; pp. 144–166. [Google Scholar]

- Kamruzzaman, P. Understanding extreme poverty in the words of the poor—A Bangladesh case study. J. Poverty 2021, 25, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A. Measuring poverty in a growing world (or measuring growth in a poor world). Rev. Econ. Stat. 2005, 87, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A. Measuring poverty. In Understanding Poverty; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Welfare, freedom and social choice: A reply. Rech. Économiques De Louvain/Louvain Econ. Rev. 1990, 56, 451–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Valuing Freedoms. Sen’s Capability Approach and Poverty Reduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bibi, S. Measuring Poverty in a Multidimensional Perspective: A Review of Literature. 2005. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=850487 (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Foster, J.; Seth, S.; Lokshin, M. A Unifi ed Approach to Measuring Poverty and Inequality; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gnangnon, S.K. Poverty volatility and poverty in developing countries. Econ. Aff. 2021, 41, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Santos, M.E. A Multidimensional Approach: Poverty Measurement & Beyond. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 112, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. Poverty Data Stories. 2019. Available online: https://kidb.adb.org/content/poverty (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Mohanty, S.K.; Vasishtha, G. Contextualizing multidimensional poverty in urban India. Poverty Public Policy 2021, 13, 234–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsay, E.A. Poverty profile and health dynamics of indigenous people. Int. Rev. Soc. Sci. Res. 2022, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsay, E.A. Productivity value chain analysis of cassava in the Philippines. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 892, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsay, E.A.; Rabajante, J.F. Measuring the unmeasurable multidimensional poverty for economic development: Datasets, algorithms, and models from the poorest region of Luzon, Philippines. Data Brief 2024, 110150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsay, E.A.; Rabajante, J.F. When machine learning meets econometrics: Can it build a better measure to predict multidimensional poverty and examine unmeasurable economic conditions? Sci. Talks 2024, 11, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meij, E.; Haartsen, T.; Meijering, L. Enduring rural poverty: Stigma, class practices and social networks in a town in the Groninger Veenkoloniën. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 79, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M.; Larsen, R.J. Measuring the immeasurable. In The Science of Subjective Well-Being; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 141–167. [Google Scholar]

- Gruijters, S.L.; Fleuren, B.P. Measuring the unmeasurable. Hum. Nat. 2018, 29, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabajante, J.F. Insights from early mathematical models of 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease (COVID-19) dynamics. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.05296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Kittur, A.; Youn, H.; Milojević, S.; Leahey, E.; Fiore, S.M.; Ahn, Y.Y. Metrics and mechanisms: Measuring the unmeasurable in the science of science. J. Informetr. 2022, 16, 101290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. Nations. Facing the Challenge of Measuring the Unmeasurable. 2012. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/news/statistics/measuring-the-unmeasurable.html (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- RA11315. Community-Based Monitoring Act of 2018. Available online: https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/2019/04apr/20190417-RA-11315-RRD.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Philippine Statistics Authority. Updated Official Poverty Statistics of the Philippines. Full-Year 2018. Poverty and Human Development Statistics Division of the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). 2018. Available online: https://rsso11.psa.gov.ph/poverty (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Philippine Statistics Authority. Official Poverty Statistics of the Philippines. First Semester of 2021. Poverty and Human Development Statistics Division of the Philippine Statistics Authority. 2021. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/poverty/index (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Philippine Statistics Authority. Official Poverty Statistics of the Philippines. Full-Year 2015. Poverty and Human Development Statistics Division of the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). 2015. Available online: https://www.psa.gov.ph/content/updated-2015-and-2018-full-year-official-poverty-statistics (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Philippine Statistics Authority. Proportion of Poor Filipinos Registered at 21.0 Percent in the First Semester of 2018. 2019. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/content/proportion-poor-filipinos-was-recorded-181-percent-2021 (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2018: The Most Detailed Picture to Date of the World’s Poorest People. Report; Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-912291-12-0. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. Initial progress in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A review of evidence from countries. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1453–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnani, A. Romanticizing the poor. In Fighting Poverty Together: Rethinking Strategies for Business, Governments, and Civil Society to Reduce Poverty; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, C.M.; Mandap, A.E.E.; Quilitis, J.A.; Bancolita, J.E.; Baris, M.A.J.; Leyso, N.L.C.; Calubayan, S.J.I. CBMS Handbook; De La Salle University Publishing House: Manila, Philippines, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, C.; Tabuga, A.; Mina, C.; Asis, R.; Datu, M. Chronic and Transient Poverty; PIDS Discussion Paper Series No. 2010-30; Philippine Institute for Development Studies: Manila, Philippines, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, C.M.; Mandap, A.B.E. Monitoring Child Poverty and Exclusion through the Community-Based Monitoring System (CBMS). DLSU Bus. Econ. Rev. 2019, 32, 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, R. Health and Economic Growth; World Health Organization: Geneve, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, D.E.; Canning, D.; Sevilla, J. The effect of health on economic growth: A production function approach. World Dev. 2004, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Well, D.N. Accounting for the effect of health on economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 1265–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Malnutrition. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/malnutrition#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- World Health Organization. DAC Guidelines and Reference Series Poverty and Health. 2003. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264100206-en.pdf?expires=1664436943&i (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- World Health Organization. Undernutrition in the Philippines: Scale, Scope, and Opportunities for Nutrition Policy and Programming. 2021. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/philippines/publication/-key-findings-undernutrition-in-the-philippines (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Bankoff, G. Blame, responsibility and agency: ‘Disaster justice’ and the state in the Philippines. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2018, 1, 363–381. [Google Scholar]

- RA10121. Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act (2009). Available online: https://lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra2010/ra_10121_2010.html (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Datt, G.; Ravallion, M. Growth and redistribution components of changes in poverty measures: A decomposition with applications to Brazil and India in the 1980s. J. Dev. Econ. 1992, 38, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, G.R.; Sumner, A. Who is the world’s poor? A new profile of global multidimensional poverty. World Dev. 2019, 126, 104716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, J.F.; Narito RR, S.; Asor, N.T.; Onsay, E.A. Comprehensive Poverty Evaluation of Rural Communities in the Philippines: Empirical Evidence from Community-Based Monitoring System (CBMS) and Econometric Modeling. Technoarete Transactions on Economics and Business Systems (TTEBS). 2023. Vol-2, Issue-1, e-ISSN: 2583-4649. Available online: https://technoaretepublication.org/economics-and-busniess-system/article/comprehensive-poverty-evaluation.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Anwar, T.; Qureshi, S.K.; Ali, H.; Ahmad, M. Landlessness and rural poverty in Pakistan [with comments]. Pak. Dev. Rev. 2004, 855–874. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, K.; Gaiha, R.; Bresciani, F. The labor productivity gap between the agricultural and nonagricultural sectors, and poverty and inequality reduction in Asia. Asian Dev. Rev. 2019, 36, 112–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizer, A.; Jackson, M.; O’Brien, R.; Persico, C. Poverty and Childhood Health. Spring/Summer. 2017. Available online: https://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/focus/pdfs/foc332f.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Sindzingre, A. The multidimensionality of poverty: An institutionalist perspective. In The Many Dimensions of Poverty; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 52–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, F. The Growth Elasticity of Poverty Reduction: Explaining Heterogeneity Across Countries and Time Periods; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Poverty and Health. 2014. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/health/brief/poverty-health (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- World Bank. Republic of the Philippines Labor Market Review: Employment and Poverty; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, A.; Doan, D.; Newhouse, D.; Nguyen, M.C.; Uematsu, H.; Azevedo, J.P. A new profile of the global poor. World Dev. 2018, 101, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vista, B.M. Exploring the Spatial Patterns and Determinants of Poverty: The Case of Albay and Camarines Sur Provinces in Bicol Region, Philippines. Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, the University of Tsukuba. 2008. Available online: http://giswin.geo.tsukuba.ac.jp/sis/thesis/Vista_Brandon.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Velarde, R.B.; Velarde, R.B. The Philippines’ Targeting System for the Poor: Successes, Lessons, and Ways Forward. World Bank, 2018. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/pt/830621542293177821/pdf/132110-PN-P162701-SPL-Policy-Note-16-Listahanan.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Sachs, J. The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Easterly, W. The big push deja vu: A review of Jeffrey Sachs’s the end of poverty: Economic possibilities for our time. J. Econ. Lit. 2006, 44, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Easterly, W. The ideology of development. Foreign Policy 2007, 161, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, D. Why foreign aid is hurting Africa. Wall Str. J. 2009, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, D. Dead Aid: Why aid is Not Working and How There is a Better Way for Africa; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rowntree, B.S. Poverty: A Study of Town Life; Macmillan: London, UK, 1901; pp. 119–120. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, J.; Greer, J.; Thorbecke, E. A class of decomposable poverty measures. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1984, 52, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobreviñas, A.B. The Community-Based Monitoring System (CBMS): An Investigation of Its Usefulness in Understanding the Relationship between International Migration and Poverty in the Philippines. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sobreviñas, A.B. Examining chronic and transient poverty using the Community-Based Monitoring System (CBMS) Data: The case of the Municipality of Orion. DLSU Bus. Econ. Rev. 2020, 30, 111–112. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, C.M. Community-Based Monitoring System (CBMS): An Overview. In Proceedings of the 2017 PEP Meeting, Nairobi, Kenya, 8–14 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dunga, S.H.; Sekatane, M.B. Determinants of employment status and its relationship to poverty in Bophelong Township. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ray, K.; Sissons, P.; Jones, K.; Vegeris, S. Employment, Pay and Poverty. Evidence and Policy Review; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski, J.J. Employment and Poverty in the Philippines; World Bank, Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/979071488446669580/employment-and-poverty-in-the-philippines (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Siddiqui, F.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Das, J.K. The intertwined relationship between malnutrition and poverty. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, M.R.L.; Valdecanas, C.M.; Reyes, O.L.; Reyes, T.M. The effects of malnutrition on the motor, perceptual, and cognitive functions of Filipino children. Int. Disabil. Stud. 1990, 12, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, W.J. Economic development and the housing problem. Philipp. Stud. 1979, 27, 210–230. [Google Scholar]

| Poverty Indicators | Household | Population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnitude | Proportion | Magnitude | Proportion | ||

| Health and Nutrition | Children under 5 years old who died Total HH with children under 5 years old = 5309 Total population of children under 5 years old = 7378 | 34 | 0.60 | 34 | 0.50 |

| Women who died due to pregnancy-related causes | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Malnourished children 0–5 years old Total number of children 0–5 years old = 5966 Total population of children aged 0–5 years old = 9010 | 369 | 6.20 | 489 | 5.40 | |

| Housing | Households living in makeshift housing | 384 | 2.70 | 1723 | 2.70 |

| Households who are informal settlers | 947 | 6.80 | 4614 | 7.30 | |

| Water and Sanitation | Households without access to safe water | 2869 | 20.50 | 13,018 | 20.60 |

| Households without access to sanitary toilet facilities | 1740 | 12.40 | 7795 | 12.30 | |

| Basic Education | Children aged 6–11 years old who are not attending elementary Total number of HH with children aged 6–11 = 6065 Total population of children aged 6–11 years old = 9867 | 1528 | 25.20 | 1765 | 17.90 |

| Children aged 12–15 years old who are not attending Junior High School Total number of HH with children aged 12–15 years old = 4498 Total population of children aged 12–15 years old = 6277 | 2059 | 45.80 | 2462 | 39.20 | |

| Children aged 16–17 years old not attending Senior High School Total number of HH with children aged 16–17 = 2523 Total population of children aged 16–17 = 2763 | 1903 | 75.40 | 2037 | 73.70 | |

| Income and Livelihood | Households with income below the poverty threshold | 8930 | 63.70 | 43,268 | 68.50 |

| Households with income below the food threshold | 7168 | 51.10 | 35,271 | 55.80 | |

| Households who experienced food shortage | 69 | 0.50 | 375 | 0.60 | |

| Unemployed members of the labor force Total number of HH with members of the labor force = 11,883 Total population of members of the labor force = 18,220 | 451 | 3.80 | 497 | 2.40 | |

| Peace and Order | Victims of crime | 84 | 0.60 | 89 | 0.10 |

| Poverty Outcomes | Isarog Sector | Poblacion Sector | Salog Sector | Ranggas Sector | Goa Municipality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | P | x | p | x | p | x | p | x | p | |

| Children under 5 years old who died | 0.23 | 0.00 | 1.13 | 0.05 | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.94 | 0.27 | 0.98 | 0.05 |

| Women who died due to pregnancy-related causes | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Malnourished children 0–5 years old | 0.78 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 0.03 | 1.89 | 0.00 | 1.29 | 0.00 |

| Households who are informal settlers | 0.62 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 0.04 | 0.90 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.61 | 0.44 | 0.00 |

| Households living in makeshift housing | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.03 |

| Households without access to safe water | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.59 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.00 |

| Households without access to sanitary toilet facilities | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.05 | −0.62 | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.83 | 0.00 |

| Household Members | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

| Children aged 6–11 years old who are not attending elementary | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 0.00 |

| Children aged 12–15 years old who are not attending Junior High School | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.04 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.00 |

| Children aged 16–17 years old not attending Senior High School | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| Unemployed members of the labor force | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.49 | 0.17 | 0.05 |

| Victims of crime | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.93 | 1.37 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.02 |

| Disaster Risk Reduction Preparedness | −0.23 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.56 | 1.00 | −1.36 | 0.00 | −1.58 | 0.00 |

| Calamity Occurrences—Typhoon | 1.79 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 1.43 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.00 |

| Calamity Occurrences—Flood | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.05 | −0.19 | 0.36 | 0.11 | 0.05 |

| Calamity Occurrences—Drought | 3.13 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 1.11 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 2.58 | 0.00 |

| Calamity Occurrences—Volcanic Eruption | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Calamity Occurrences—Landslide/Mudslide | 1.35 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.87 | 0.00 |

| Households who are informal settlers × Household Members | 0.08 | 0.50 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.15 | 0.02 |

| Households living in makeshift housing × Children under 5 years old who died | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| Households without access to safe water × Children under 5 years old who died | 1.02 | 0.03 | 1.68 | 0.03 | 0.97 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.05 |

| Households without access to safe water × Household Members | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Households without access to safe water × Households who are informal settlers | 1.38 | 0.01 | 1.80 | 0.01 | 1.40 | 0.05 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| Households without access to safe water × Households living in makeshift housing | 0.58 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.07 |

| Households without access to sanitary toilet facilities × Households who are informal settlers | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.87 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| Households without access to sanitary toilet facilities × Households living in makeshift housing | 0.12 | 0.89 | 2.71 | 0.67 | 3.23 | 0.03 | 0.95 | 0.18 | 1.21 | 0.33 |

| DRRP × Makeshift Housing | −0.18 | 0.02 | −1.24 | 0.02 | −0.39 | 0.02 | −0.83 | 0.09 | −0.63 | 0.00 |

| DRRP × Child Mortality | −0.20 | 0.12 | −0.08 | 0.20 | −0.21 | 0.20 | −0.32 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.00 |

| DRRP × Total Household Members | −0.25 | 0.00 | −0.38 | 0.00 | -0.57 | 0.44 | −0.89 | 0.22 | −0.27 | 0.02 |

| DRRP × Calamity Occurrences | −0.88 | 0.02 | −0.23 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.39 | −0.45 | 0.00 | −0.66 | 0.00 |

| Constant | −2.22 | 0.00 | −1.00 | 0.00 | −1.32 | 0.00 | −0.32 | 0.15 | 2.31 | 0.00 |

| Poverty Outcomes (v) | Isarog Sector | Poblacion Sector | Salog Sector | Ranggas Sector | Goa Municipality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | P | x | p | x | p | x | P | x | p | |

| Children under 5 years old who died | 0.21 | 0.00 | 1.16 | 0.04 | 0.93 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.27 | 0.82 | 0.02 |

| Women who died due to pregnancy-related causes | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Malnourished children 0–5 years old | 0.76 | 0.04 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.03 | 1.86 | 0.00 | 1.16 | 0.00 |

| Households who are informal settlers | 0.60 | 0.03 | 0.84 | 0.00 | 0.92 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.00 |

| Households living in makeshift housing | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.03 |

| Households without access to safe water | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.00 |

| Households without access to sanitary toilet facilities | 0.72 | 0.00 | 0.83 | 0.00 | −0.60 | 0.04 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.00 |

| Household Members | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.00 |

| Children aged 6–11 years old who are not attending elementary | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.00 |

| Children aged 12–15 years old who are not attending Junior High School | 0.35 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.00 |

| Children aged 16–17 years old not attending Senior High School | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.35 | 0.00 |

| Unemployed members of the labor force | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 0.59 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.05 |

| Victims of crime | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.93 | 1.34 | 0.21 | 0.53 | 0.02 |

| Disaster Risk Reduction Preparedness | −0.25 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.54 | 1.00 | −1.39 | 0.00 | −0.53 | 0.00 |

| Calamity Occurrences—Typhoon | 1.77 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 1.45 | 1.00 | −0.03 | 0.63 | 0.85 | 0.00 |

| Calamity Occurrences—Flood | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.05 | −0.22 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Calamity Occurrences—Drought | 3.11 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 1.13 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 1.10 | 0.00 |

| Calamity Occurrences—Volcanic Eruption | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Calamity Occurrences—Landslide/Mudslide | 1.33 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 1.08 | 1.00 | −0.03 | 0.27 | 0.63 | 0.00 |

| Households who are informal settlers × Household Members | 0.06 | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| Households living in makeshift housing × Children under 5 years old who died | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.00 |

| Households without access to safe water × Children under 5 years old who died | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.71 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 0.05 |

| Households without access to safe water × Household Members | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| Households without access to safe water × Households who are informal settlers | 1.36 | 0.01 | 1.83 | 0.01 | 1.42 | 0.05 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 1.28 | 0.06 |

| Households without access to safe water × Households living in makeshift housing | 0.56 | 0.03 | 0.94 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.07 |

| Households without access to sanitary toilet facilities × Households who are informal settlers | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.99 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.21 | 0.57 | 0.04 |

| Households without access to sanitary toilet facility × Households living in makeshift housing | 0.10 | 0.90 | 2.74 | 0.67 | 3.25 | 0.03 | 0.92 | 0.08 | 1.77 | 0.03 |

| DRRP × Makeshift Housing | −0.20 | 0.00 | −1.21 | 0.02 | −0.37 | 0.02 | −0.86 | 0.09 | −0.68 | 0.00 |

| DRRP × Child Mortality | −0.22 | 0.22 | −0.05 | 0.20 | −0.19 | 0.20 | −0.35 | 0.00 | −0.22 | 0.00 |

| DRRP × Total Household Members | −0.27 | 0.00 | −0.35 | 0.00 | −0.25 | 0.44 | −0.92 | 0.02 | −0.47 | 0.01 |

| DRRP × Calamity Occurrences | −0.80 | 0.02 | −0.20 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.39 | −0.48 | 0.00 | −0.35 | 0.00 |

| Constant | −2.24 | 0.00 | −0.97 | 0.00 | −1.30 | 0.00 | −0.35 | 0.15 | 1.19 | 0.00 |

| Indicators | Policy Mapping | Policy Targeting | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health and Nutrition | Child Mortality |

|

|

| Pregnancy or Maternal Mortality |

|

| |

| Malnutrition of Children |

|

| |

| Housing | Dwellers in Makeshift Housing |

|

|

| Informal Settlers |

| ||

| Water and Sanitation | Access to Safe Drinking Water |

|

|

| Access to sanitary toilet facilities |

|

| |

| Basic Education | Children aged 6–11 years old who are not attending elementary |

|

|

| Children aged 12–15 years old who are not attending Junior High School |

|

| |

| Children aged 16–17 years old not attending Senior High School |

|

| |

| Poverty based on Income Threshold |

|

| |

| Poverty based on Food Threshold |

| ||

| Food Shortage |

|

| |

| Unemployment |

| ||

| Victims of crime |

|

| |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Onsay, E.A.; Rabajante, J.F. Measuring the Unmeasurable: Decomposing Multidimensional Rural Poverty and Promoting Economic Development in the Poorest Region of Luzon, Philippines. Societies 2024, 14, 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14110235

Onsay EA, Rabajante JF. Measuring the Unmeasurable: Decomposing Multidimensional Rural Poverty and Promoting Economic Development in the Poorest Region of Luzon, Philippines. Societies. 2024; 14(11):235. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14110235

Chicago/Turabian StyleOnsay, Emmanuel Azcarraga, and Jomar Fajardo Rabajante. 2024. "Measuring the Unmeasurable: Decomposing Multidimensional Rural Poverty and Promoting Economic Development in the Poorest Region of Luzon, Philippines" Societies 14, no. 11: 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14110235

APA StyleOnsay, E. A., & Rabajante, J. F. (2024). Measuring the Unmeasurable: Decomposing Multidimensional Rural Poverty and Promoting Economic Development in the Poorest Region of Luzon, Philippines. Societies, 14(11), 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14110235