Abstract

Background: Due to global technological advances, psychology professionals have experienced constant changes in their daily routines. The field of career development and vocational psychology is no different. Amplified by the adjustments brought about by the circumstances of the pandemic, there has been an increased demand for and development of various distance intervention methodologies. Methods: This study presents a systematic review of distance career interventions, focusing on (1) rationale, (2) groups of the population, (3) structure, (4) evaluation, and (5) outcomes and recommendations. Eleven keywords, three databases, and five eligibility criteria were defined. Results: Sixteen articles were collected for analysis. The results showed a predominance of (1) career construction theory and social cognitive theory rationales, (2) a sample of university students, (3) group career intervention, (4) pre- and post-test evaluation systems, and (5) effects in different dimensions and recommendations about intervention research design. Conclusions: Although there has been an increase in the number of publications in recent years, few studies evaluate distance career interventions. There are also few studies with different target populations. In this sense, indications for future interventions and studies are given, as well as the implications of these studies for practice.

1. Introduction

With technological advancements on a global scale, there have been continuous changes in the daily routines of psychology professionals [1]. As a result, there was a need to adapt the psychological interventions carried out by these professionals in their various fields of expertise [2]. The field of career development and vocational psychology is no exception. Reinforced by the changes demanded by the pandemic context, the demand for and development of different distance intervention practices has increased [3,4]. Career interventions are referred to in the literature as a broad set of activities designed to enrich personal and professional growth by helping people explore, generate, and execute various decisions relevant to their careers [5]. These interventions encompass a set of aids designed to help individuals overcome the challenges encountered in defining their career paths [5,6,7]. The use of technology in interventions is not a novel phenomenon, but the way it is used is changing and growing. Since the 1960s, the relationship between technologies and career interventions has evolved, characterized by a complex interplay between potential advantages and disadvantages [8]. Distance intervention was initially only used by sending correspondence (e.g., a letter) and then by making telephone calls.

In recent times, career interventions have been incorporating information and communication technologies (ICT), either as a resource (e.g., through the use of a website with information) or as a means through which it has been possible to carry out these interventions (e.g., through the use of videoconferencing platforms) [9].

Distance career interventions are referred to by a variety of terms. In other words, according to the literature, computer-assisted career counseling can take four distinct forms: computer-assisted career guidance systems (CACGS), computerized career assessment, electronic sources of access to career information, and distance or online career counseling [10,11]. In this way, people can access professional counseling guided by psychologists through remote channels, such as cell phones, email, online chat, or video conferencing [12,13,14]. Thus, the types of services listed vary. Therefore, in this article, we will assume that a distance career intervention requires the guidance of a psychologist and a geographic distance between the psychologist and the client. However, the connection is mediated by information and communication technologies, which may be synchronous or asynchronous.

Distance services aim to reach individuals who have traditionally been underserved or who are looking for the convenience of distance assistance. Thus, the use of new technologies as mediators of distance career interventions brings with it advantages and disadvantages. Distance services’ effectiveness requires individuals to have auditory and physical privacy to promote client self-disclosure and maintain confidentiality, raising ethical issues that pose challenges in these new contexts [15]. These services have advantages, such as reducing costs and extending reach to specific populations. They also create new communities of social support, especially beneficial for those affected by geographic distances or mobility restrictions [16,17]. Indeed, the growing importance of distance career intervention is evident, especially in areas with limited access to face-to-face services, where this modality provides accessible and inclusive solutions, allowing more individuals to receive professional support efficiently and without geographical barriers [16,17]. However, disadvantages include challenges in accessing physical media, financial constraints, and possible gaps in an individual’s digital literacy, all of which can hinder access to technology [18,19]. Thus, persistent concerns about its effectiveness and potential benefits also remain a focus of study [8].

Distance career interventions are thus a key point of study. In particular, they can be useful in responding to the needs of developing generations. The emerging characteristics of the Generation Z population, marked by impatience, internet dependency, fragmented thinking, and hyperactivity, have further influenced the landscape of career guidance [20]. Leveraging digital technologies and tools becomes promising for organizing and conducting career guidance, aligning with the psychophysiological characteristics of this generation. Although the recognition of the distance modality is increasing, evidence of its empirical validity is still scarce. However, existing studies show favorable results [21,22]. While a significant portion of the literature on career intervention has concentrated on distance counseling, the diverse nature of these interventions warrants ongoing exploration and consideration.

Study Goals

Some literature reviews contribute significantly to knowledge about career interventions. On the one hand, some systematic reviews focus on the type of technology used in career interventions (e.g., [23]), while others focus on other objectives. This is the case, for example, with the study by Soares et al. [7], who undertook the task of synthesizing the evidence on career interventions aimed at university students from 2000 to 2021, providing a comprehensive overview of this time interval. Other studies also stand out in this panorama. Oliveira et al. [24] conducted a review focused on career interventions delivered between 2010 and 2014, offering valuable insights into developments during this period. Hughes et al. [25] looked at research carried out between 1996 and 2016, providing a broad perspective on career interventions and educational programs. Langher et al. [26] and Whiston et al. [27] contributed meta-analyses, offering a comprehensive quantitative analysis of the effectiveness of career interventions. Kim et al. [28] conducted a scooping review, investigating what is known about technology-based employment interventions for individuals with autism, examining how these interventions have been conducted, and providing valuable insights into this specific area of study. These collective analyses serve a pivotal function in the formation of a comprehensive understanding of practices and progress. However, the above studies take a generic approach to career interventions and some to specific populations. There has been no detailed analysis of the characteristics of online career interventions.

A distant psychological career intervention comprises a rationale and methodology, including implementation processes, target population, and assessment tools used to support the results and recommendations. This systematic literature review aims to synthesize the existing literature on distance career interventions, focusing on five main aspects: (1) rationale, (2) target population, (3) intervention structure, (4) evaluation (timing of evaluation, instruments used), and (5) results and practical recommendations. Based on this objective, this review will consolidate knowledge about distance career interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

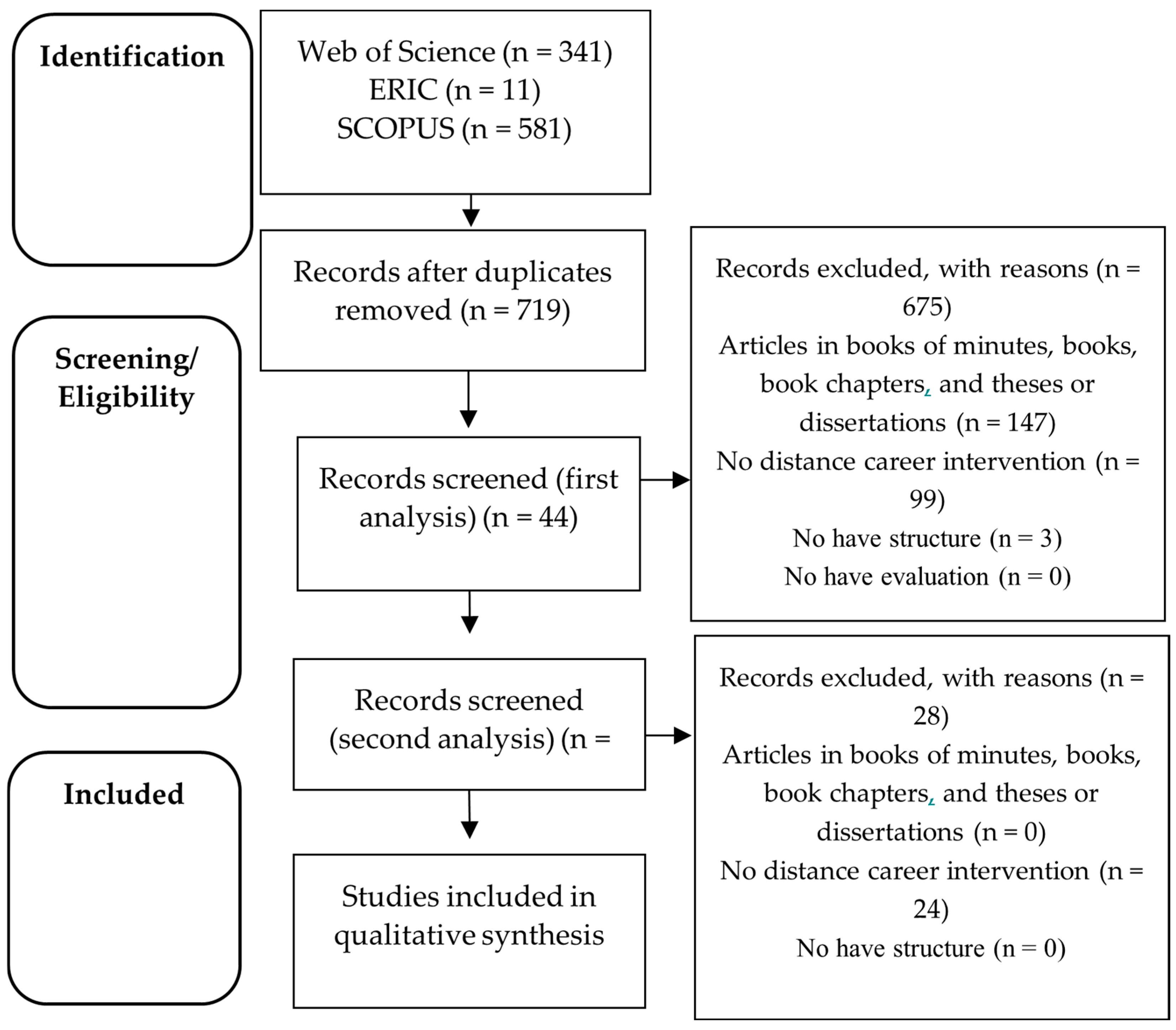

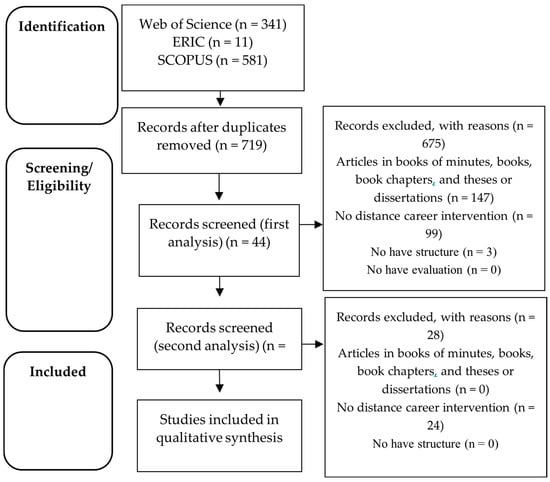

The PRISMA protocol (Figure 1, see Appendix A for more details) [29] was used to carry out this systematic literature review and to answer the following questions: (Q1) “What is the rationale behind distance career interventions?”; (Q2) “What are the groups of the population target of these interventions?”; (Q3) “What is the structure of at-distance career interventions?”; (Q4) “How have at-distance career interventions been evaluated?”; and (Q5) “What outcomes and recommendations have been published?”

Figure 1.

Research and selection process.

2.1. Databases

Three databases were used: two multidisciplinary databases (Web of Science and SCOPUS) and one focused on education themes (ERIC). The survey was conducted between the 6th and the 8th of September 2023.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Five eligibility criteria and eleven keywords were defined to guide the selection of articles. The five eligibility criteria included the year of publications, the description of the distance career interventions, the structure (i.e., number of sessions or frequency), the evaluation, and the outcomes. Specifically, only scientific articles published between 2010 and 2023 and written in any language were considered. Furthermore, the selected scientific articles should include distance career interventions, the structure of these interventions, the evaluation, and the outcomes. The 11 keywords were combined by the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR”: (“Career intervention” OR “Career guidance” OR “Career education” OR “Career counseling” AND Distance OR Online OR Technology OR Internet OR ICT OR Digital OR Platforms”). This combination of keywords was the subject of a full-text search of the articles. Exclusion criteria included articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria and the publication of articles in books of minutes, books, book chapters, theses or dissertations, and articles that did not allow access to the full text.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

First, each article’s title and abstract were analyzed. Our objective was to understand if each study was focused on presenting a career intervention with an evaluation system. Secondly, to minimize biases, two researchers, independently, with knowledge and experience in research in the field of vocational and career development psychology, read each accepted article from the previous step, following the eligibility criteria. Thirdly, only the articles answering those criteria remained for analysis. For both filtering stages, that is, reading the titles and abstracts and reading the articles in full, disagreements were resolved through discussions between the researchers. A third researcher resolved any remaining disagreements. After article selection, the information was organized and summarized according to the following topics: rationale, groups of the population, career intervention structure, evaluation, recommendation, outcomes, and interventions.

2.4. Assessment of Bias

The first jury carried out the initial screening and the first and second juries carried out the inclusion and exclusion criteria and eliminated any doubts that arose. If any doubts remained, a third jury was used. The methodological assessment was carried out using the ROBINS-I bias analysis scale [30].

3. Results

A total of 933 articles were identified through database searches, as described in the data extraction and analysis section. The articles were initially exported to Microsoft Excel to eliminate duplicates. After eliminating duplicates, 719 (77.1%) articles remained. This initial screening, based on title and abstract, assessed whether the articles met the eligibility criteria. In case of doubt, the article went to the second stage of review.

As illustrated in Figure 1, among the 719 non-duplicated articles, the first screening phase identified 147 articles that were books of minutes, books, book chapters, or theses or dissertations. Additionally, 99 articles were excluded as they lacked a career intervention, and 3 articles were excluded as they lacked an intervention structure. The remaining 44 went on to the second screening phase, where the same eligibility criteria were applied to the full article reading. Out of these, 28 articles were excluded. Ultimately, 16 articles [6,22,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] were selected for the systematic literature review (Figure 1).

The majority of the studies were published after 2020, with 50% (n = 8) published between 2015 and 2019. The sources of these studies varied, with 62.5% (n = 10) coming from SCOPUS, 12.5% (n = 2) from Web of Science, and the remaining studies from both sources (25% [n = 4]). The field of the journals in which most of the selected articles were published focused on the psychology and vocational psychology of career development, accounting for 52.9% (n = 9) of the studies. The articles selected come from a diverse range of countries, with 31.3% (n = 5) from Asia, 31.3% (n = 5) from Europe, 31.3% (n = 5) from America, and 6.3% (n = 1) from Africa. Information regarding (Q1) “What are the rationale behind distance career interventions?”, (Q2) “What are the groups of the population target of these interventions?”, and (Q3) “What is the structure of at-distance career interventions?” is presented in Table 1. Information about (Q4) “How have at-distance career interventions been evaluated?” is presented in Table 2, and information about (Q5) “What outcomes and recommendations have been published?” is presented in Table 1. The results regarding each question will be presented in the following section.

Table 1.

Research summary about the rationale, groups of the population, intervention structure, outcomes, and recommendations (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q5).

Table 2.

(Q4) “How have at-distance career interventions been evaluated?”: Part 1.

3.1. Distance Career Intervention Rationale (Q1)

Table 1 presents the information that answers the first research question (Q1) concerning the rationale for career distance interventions. Among the sixteen articles included, one (6.3%) did not provide a detailed account of the theoretical framework underpinning the applied career intervention [38]. Out of the sixteen analyzed articles, ten (62.5%) reported following the career construction theory [22,32,35,36,39,40,41,42,44], and the social cognitive theory was mentioned in five (31.3%) articles [31,33,34,40,43], the trait-factor theory in one article [31] and one article reported following the cognitive information processing (CIP) theory [6].

3.2. Distance Career Intervention Groups of Population (Q2)

Concerning the population groups targeted by the distance career intervention and answering the second research question (Q2), as illustrated in Table 1, ten (62.5%) focused their study on a sample of university students [22,32,35,36,37,39,40,42,43,44], two (12.5%) in primary to high school students [6,37], three (18.8%) in the adult population [31,33,34], and one (6.3%) in the unemployed population.

3.3. Distance Career Intervention Structure (Q3)

To answer the third research question (Q3) concerning the structure of distance career interventions, as mentioned in Table 1, three different modalities of interventions emerged: group career intervention was mentioned in twelve articles (75%) [6,22,31,32,33,35,36,37,39,42,43,44], followed by a combination of individual and group counseling in three articles (18.8%) [38,40,41], and individual career intervention in one article (6.3%) [34]. For the sessions’ numbers and duration, 16 articles provided information. The sessions ranged from 1 [34] to 16 (e.g., [38]), lasting 45 min (e.g., [6]) to 180 min (e.g., [42]) or over 2 weeks [35].

3.4. Distance Career Intervention Evaluation System (Q4)

Table 2 presents some of the information that answers the fourth research question (Q4), giving details of how the interventions were evaluated. The table is divided into five topics, into which one topic is subdivided: (1) pre- and post-testing (n = 14, 87.5%), (2) follow-up (n = 6, 37.5%), (3) control group (n = 11, 68.8%), (4) compare group (n = 4, 25%), and satisfaction evaluation (n = 4, 25%).

Table 3 presents the remaining information that answers the fourth research question (Q4), with which instruments the interventions were evaluated. The table is divided into six topics, which indicate the dimension evaluated by the intervention (1) career decision-making (n = 10, 62.5%) [6,22,31,32,33,35,36,37,39,43], (2) career adaptability (n = 5, 31.3%) [35,40,41,42,44] (3) vision about the future (n = 3, 18.8%) [41,42,44], (4) satisfaction (n = 2, 12.5%) [42,44], (5) other variables (n = 9, 56.3%) [31,32,34,35,36,40,41,42,44], and (6) questionnaires designed for the study purpose (n = 6, 37.5%) [31,34,35,37,38,41]. The following instruments were used to assess career decision-making: Career Decision Scale [45], Career Decision Profile [46], Identity and Career Decision Scale [47], Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form [48], Career Decision-Making Difficulties Questionnaire [49], Self-efficacy questionnaire for career decision-making [50], Vocational Identity Status Assessment [51], and Career Maturity Inventory (CMI)-Form C [52]. The following instruments were used to assess career adaptability: the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale [53], the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale [54], and the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale [55]. The following instruments were used to assess the vision of the future: Design My Future [56], Thoughts about the future [57,58], Propensity for inclusive and sustainable actions for the future [59], Design My Future [60], and Visions About Future [61]. The Satisfaction with Life Scale [62] was used to assess satisfaction.

Table 3.

(Q4) “How have at-distance career interventions been evaluated?”: Part 2.

Several other constructs were also evaluated with the following instruments: the Career Exploratory Behaviors Scale [63], Occupational Alternatives Question [64], the hardiness scale by Kobasa [65], Psychological Capital Questionnaire [66], Career Exploration Survey [67], Self-reflection and Insight Scale [68], Current Perception Scale of Professional Development [69], Self-perceived Employability Scale [70], Ongoing self-reflection [71], Courage [72], Multidimensional Assessment of COVID-19-Related Fears [73], Subjective Risk Intelligence Scale [74], and General Self-efficacy Scale [75,76]. Finally, different authors have opted to develop questionnaires to assess specific issues within the context of the study. For example, satisfaction with current and future career situation [31], exploratory consultation quality [34], exploratory consultation effectiveness [34], satisfaction with intervention [34,38], website assessment scale by the career counseling experts [36], website assessment scale by the computer engineering experts [36], user satisfaction assessment with the career counseling website [36], and social validity [41].

3.5. Distance Career Intervention Evaluation Outcomes and Recommendations (Q5)

The relationship between the evaluation outcomes targeted by the distance career intervention and answering the fifth research question (Q5) can be seen in Table 3. The studies showed positive post-test effects on the dimensions of career adaptability in five (31.3%) studies [35,40,41,42,44], future orientation and propensity to identify inclusive and sustainable actions in the future in three (18.8%) studies [41,42,44], and career exploration in two (12.5%) studies [31,34]. One study (6.3%) showed no differences in the career decision-making dimension [35].

Comparing the intervention group with the control group, eleven (68.8%) studies showed favorable effects on the dimensions of self-efficacy in decision-making and uncertainty [6,22,31,32,33,36,37,39,43,44], two (12.5%) in career adaptability [40,44], one (6.3%) in the propensity to identify inclusive and sustainable actions in the future [41], one (6.3%) in life satisfaction [42], one (6.3%) in career exploration [31], one (6.3%) in psychological capital [32], two (12.5%) in hardiness [32,37], one (6.3%) in fear [44], one (6.3%) in self-reflection and insight [35], one (6.3%) in the ability to consider situations of risk and uncertainty [44], one (6.3%) in courage [42], one (6.3%) in the perception of professional development [40], and one (6.3%) in the perception of employability [40]. One study (6.3%) showed that there were no differences in the life satisfaction dimension [44].

One study (6.3%) found favorable differences at follow-up on the dimensions of career adaptability and perceived employability [40]. Regarding the other dimensions assessed quantitatively and qualitatively through questionnaires created for this purpose, we found favorable effects when comparing the intervention group with the control group in the dimensions of current and future satisfaction with the career in one study (6.3%) [31], in satisfaction with the intervention and the moderator also in one study (6.3%) [34], in satisfaction with the intervention and the psychologist in one study (6.3%) [38] in satisfaction with the intervention and the psychologist in one study (6.3%) [38], evaluation of the websites used in one study (6.3%) [36], and evaluation of the intervention and satisfaction with it in one study (6.3%) [41].

The practical and scientific recommendations referred to in the studies were categorized into three groups in an attempt to answer (Q5) of this study, as illustrated in Table 1. The first group on intervention research design (n = 14, 87.5%) refers to the research design of the intervention and the methodology used in the study of distance career interventions (i.e., research methods, sample selection, instruments, control groups, comparison groups, and data analysis techniques). The second group on intervention guidelines (n = 8, 50%) refers to studies that provide specific guidelines or frameworks for the implementation of distance career interventions (i.e., aspects such as intervention components, strategies, recommended activities, and improvements). The third group on training (n = 1, 6.3%) refers to studies that guide the education or training of the psychologists who will deliver the distance career intervention.

Intervention research design. Regarding the design of intervention research, three (56.3%) articles recommend the expansion of research that evaluates the effectiveness of interventions using more representative samples [35,40,44]. Eleven (68.8%) articles refer to the importance of involving a wider variety of participants, including more men (gender balance), representative samples from different regions and different age groups, from children to the elderly [6,32,33,36,37,38,39,41,42,43,44]. Two (12.5%) articles recommend including samples that involve people with physical disabilities or mental disorders [32,37]. 2 (12.5%) articles recommend the inclusion of different socioeconomic and cultural groups [32,37]. In addition, seven (43.8%) articles recommend the use of longitudinal approaches [6,32,36,37,39,40,44], five (31.3%) recommend the including control or comparison groups [31,40,41,42,44], and three (18.8%) recommend monitoring at different intervals after the intervention [41,42,44]. Three (18.8%) articles suggest that future studies investigate the differences between distance and in-person interventions [6,31,36], and four (25%) the exploration of different methodologies, instruments, and effectiveness indicators [6,40,43,44]. Six (37.5%) articles recommend the inclusion of quantitative and qualitative assessments, the analysis of individual skills, such as reading and writing abilities, as well as physical and personality characteristics [6,32,36,37,40,42].

Intervention guidelines. In this domain, one (6.3%) article recommends the implementation of career intervention interventions by different psychologists [40], and two (12.6%) recommend varying the frequency and duration of interventions [31,43]. Two (12.6%) articles recommend studying other variables that may affect the success of online career intervention [32,37]. One (6.3%) article recommends the inclusion of additional longer face-to-face sessions and longer sessions [33]. On the other hand, one (6.3%) article recommends the continuous improvement of the tools used, along with reducing the amount of text and increasing interactivity [31]. Two (12.6%) articles recommend testing new formats to involve the psychologist, such as creating lists of frequently asked questions and asking clients for stories [31,34], and one (6.3%) also recommends the use of evidence-based approaches and tools that help organize their thoughts [34]. Finally, two (12.6%) recommend assessing the intervention model in different ways, including with a larger number of participants and without individual sessions [35,40].

Training. In this context, one (6.3%) article recommends the inclusion of training programs for psychologists that include adaptations aimed at improving the quality and effectiveness of the course and the training of trainers, as well as investing in the training and constant updating of trainers [43].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This systematic literature review attempted to summarize the evidence regarding distance career interventions. The number of articles that met the inclusion criteria was 16, which were subsequently read and detailed regarding the rationale, intervention structure, evaluation system, intervention outcomes, and recommendations.

Most studies report having at least one theoretical framework for constructing career intervention (Q1). Career construction theory and social cognitive career theory stand out among the theoretical rationales. This result is consistent with the systematic literature review study by Soares et al. [7]. In other words, the theoretical bases chosen to support the interventions, even the distance interventions, are similar. Newer theories, such as life design within career construction theory and social cognitive career theory, are increasingly being used in preference of more traditional approaches.

Concerning the population groups targeted by the interventions, university students seem to predominate (Q2). The observed outcome appears to be contingent upon the fact that career interventions are oriented toward Generation Z. This may be a generation that finds it easier to handle technology. It is also a generation that, given its characteristics [20], will be more likely to use these distance intervention methods. On the other hand, higher education institutions make it easier for them to access the internet. The difficulty of accessing the internet is one of the disadvantages of this type of intervention, which is evident in the literature [18,19].

Regarding the structure of distance interventions (Q3), group career interventions predominate. This result is similar to previous reviews with specific populations [7]. However, the individual intervention modality is also mentioned, as well as the combination of individuals and groups in the same intervention. Especially due to the number and duration of the sessions, the articles are very heterogeneous, so there is no unity on this topic. This shows that the number of sessions and their duration may be related to the approach taken, the population, or the theme in focus.

According to the evaluation of distance interventions (Q4), the majority of studies used pre- and post-test evaluation, as well as the use of a control group. It should also be noted that decision-making is the most evaluated dimension among the studies included, focusing on difficulties in career decision-making, self-efficacy in career decision-making, identity, and maturity. These results may be due to the aforementioned rationale, as these variations are consistent with it. The results of distance interventions mostly support the effectiveness of the interventions, which is in line with previous review studies with specific populations (e.g., [28]). With this information, it is possible to verify the importance of distance career interventions, as well as the continuation of these lines of research despite previous review studies concluding that face-to-face career intervention has higher efficacy results than distance [27]. However, this fact reinforces the importance of studying these interventions and the critical ingredients that can favor their results because these distance interventions have advantages, such as the possibility of reaching different audiences that face-to-face interventions cannot always reach [16,17]. Most of the studies presented recommendations regarding intervention research design. Intervention research design offers a dynamic approach to investigating the impact of specific interventions, highlighting their effectiveness and relevance in practical contexts. Therefore, future interventions must consider whether their sample is representative, which supports the generalization of results. On the other hand, studying specific populations will provide more knowledge to intervene with them. It is suggested that these interventions be evaluated over time, which will make it possible to understand their effects. It is also essential to compare them with control groups and comparison groups with face-to-face intervention to understand the differences and commonalities. Guidelines for interventions provide structured frameworks for the implementation and assessment of intervention strategies, ensuring consistency and efficacy in addressing specific issues or challenges. It would be beneficial to ensure that distance career interventions are conducted by different psychologists and that they can be evaluated. This line of study could contribute to an understanding of the impact that the psychologist himself can have on the effects of the intervention. Conversely, it is crucial to assess various variables and ascertain the efficacy of the interventions for all problems. Training programs for psychologists play a pivotal role in equipping professionals with the necessary skills and knowledge to address a diverse range of psychological issues effectively.

Another fact to reflect on is that most studies focus on the Asian, European, and American continents. This may also be related to the ease of access to the internet.

On the other hand, the results showed that the advantages and disadvantages of this type of intervention are clear. On the one hand, distance interventions facilitate access to different audiences, but on the other hand, many audiences may still have difficulty accessing them. In other words, distance career interventions offer a crucial opportunity to reach disadvantaged populations, such as people in rural areas with reduced mobility or in vulnerable socioeconomic contexts. It is essential to recognize the impact of the digital divide. Unequal access to technologies, especially to quality internet, remains a significant barrier, limiting the reach of these interventions. Therefore, strategies to mitigate the digital divide, such as investing in technological infrastructure and offering digital training, are essential to ensure that the benefits of distance career interventions are effectively accessible to all populations, promoting career counseling in a more inclusive way. It is also important to take ethical issues into account when implementing this type of intervention, and this may not always be possible, preventing its implementation.

It should be noted that this article has focused on a very concise definition of distance career interventions. Even so, with the development of artificial intelligence and all the underlying technologies, this is becoming increasingly a topic of study with an increasing tendency to focus. Although this systematic literature review provides relevant information, there are some limitations to consider. Firstly, the studies focus on publications from only two databases, as no article was selected from ERIC. This resulted from the fact that one of the exclusion criteria was articles in books of minutes, books, book chapters, and theses or dissertations. These topics concern researchers continuing to develop, implement, and evaluate distance career interventions, considering different databases and types of published work. In summary, this research offers significant insights for career counselors and governmental and social organizations seeking to design and implement distance career interventions. In future studies, it would be important to deepen the evidence of the literature produced on the effects of face-to-face career interventions compared to those carried out at a distance, in different geographical and social contexts, considering more vulnerable populations and how public policies can help overcome the barriers associated with difficulties in accessing digital tools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.; M.d.C.T. and A.D.S.; methodology, C.S. and A.D.S.; investigation, C.S.; C.C.; M.d.C.T. and A.D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, C.S.; M.d.C.T. and A.D.S.; supervision, M.d.C.T. and A.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted at the Psychology Research Centre (CIPsi/UM) School of Psychology, University of Minho, supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through the Portuguese State Budget (UIDB/01662/2020) and by the Psychology Association of the University of Minho (APSi-UMinho).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist Item | Location Where Item Is Reported |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Page 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | Page 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | Pages 1–4 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | Pages 3 and 4 |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | Page 4 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists, and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | Pages 4 and 5 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | Page 4 |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Pages 4 and 5 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Pages 4 and 5 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | Pages 4 and 5 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | Pages 4 and 5 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Pages 4 and 5 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | Pages 5 and 6 |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | Pages 4 and 5 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | Pages 4 and 5 | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | Pages 4 and 5 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | Pages 4 and 5 | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | ||

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | ||

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | Page 4 |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | Page 4 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | Pages 5 and 6 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | Pages 5 and 6 | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | Pages 5–15 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | Anexo |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | Appendix |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | ||

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | Pages 4–15 | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | ||

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | Appendix |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | Pages 15–17 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | Pages 15–17 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | Pages 15–17 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | Pages 15–17 | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | ||

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | ||

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | Title page |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | Title page |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | |

| From [77]. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/. | |||

References

- Dores, A.R.; Geraldo, A.; Carvalho, I.P.; Barbosa, F. The Use of New Digital Information and Communication Technologies in Psychological Counseling during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Rodriguez, A.; De La Rosa-Gómez, A. A Perspective on How User-Centered Design Could Improve the Impact of Self-Applied Psychological Interventions in Low- or Middle-Income Countries in Latin America. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 4, 866155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margevica, L.; Smitiņa, A. Self-assessment of the digital skills of career education specialists during the provision of remote services. World J. Educ. Technol. Curr. Issues 2021, 13, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, J.P.; Kettunen, J.; Vuorinen, R. The role of practitioners in helping persons make effective use of information and communication technology in career interventions. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2020, 20, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gati, I.; Levin, N. Making better career decisions. In APA Handbook of Career Intervention, 2nd ed.; Hartung, P.J., Savickas, M.L., Walsh, W.B., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Chen, H.; Ling, H.; Gu, X. An Online Career Intervention for Promoting Chinese High School Students’ Career Readiness. Front. Psychol. 2022, 22, 815076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, J.; Carvalho, C.; Silva, A.D. A systematic review on career interventions for university students: Framework, effectiveness, and outcomes. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2022, 31, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, J.P.; Makela, J.P. Ethical issues associated with information and communication technology in counselling and guidance. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2014, 14, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, J.P.; Osborn, D.S. Using information and communication technology in delivering career interventions. In APA Handbook of Career Intervention, 2nd ed.; Hartung, P.J., Savickas, M.L., Walsh, W.B., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.D.; Ryan Krane, N.E. Four (or five) sessions and a cloud of dust: Old assumptions and new observations about career counseling. In Handbook of Counseling Psychology, 3rd ed.; Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 740–766. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, P.A.; Hitch, J.L. Occupational classification and sources of occupational information. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work; Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 382–413. [Google Scholar]

- Bright, J.E.H. If you go down to the woods today you are in for a big surprise: Seeing the wood for the trees in online delivery of career guidance. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2015, 43, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flederman, P.; Watts, A.G. Career helplines: A resource for career development. In Handbook of Career Development: International Perspectives; Arulmani, G., Bakshi, A.J., Leong, F.T.L., Watts, A.G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.; Vigano, N. Online counseling: A narrative and critical review of the literature. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 69, 994–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baier, A. The Ethical Implications of Social Media: Issues and Recommendations for Clinical Practice. Ethics Behav. 2019, 29, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, F.; Henriques, S.; Cardoso, T.; Barros, D.; Goulão, M.F. E-learning in Higher Education: Academic factors for student permanence. In Climate Literacy and Innovations in Climate Change Education—Distance Learning for Sustainable Development; Azeiteiro, U.M., Leal Filho, W., Aires, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.D.; Pinto, J.C.; Taveira, M.C. Career Self-management: Evaluation of an intervention with culturally diverse samples. In Proceedings of the Atas 5th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 7–9 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barak, A. Ethical and Professional Issues in Career Assessment on the Internet. J. Career Assess. 2003, 11, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorinen, R.; Sampson, J.P. Ethical concerns in the design and use of e-guidance. In Report Prepared for the European Commission as Part of the ICT Policy Support Programme for the “e-Guidance and e-Government Services Project” (CIP ICT PSP 224971); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ostroha, M.; Drushlyak, M.; Shyshenko, I.; Naboka, O.; Proshkin, V.; Semenikhina, O. On the Use of Social Networks in Teachers’ Career Guidance Activities. E-learning 2021, 13, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettunen, J.; Sampson, J.P. Challenges in implementing ICT in career services: Perspectives from career development experts. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2019, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pordelan, N.; Sadeghi, A.; Abedi, M.R.; Kaedi, M. Promoting student career decision-making self-efficacy: An online intervention. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, E.; Raposo, M.; Campos, S. El Uso de Tecnologías en la Orientacíon Profesional: Una Revisíon Sistemática. Rev. Esp. Orientac. Psicopedag. 2022, 33, 40–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.T.; Teixeira, M.A.P.; Dias, A.C.G. Systematic literature review on characteristics of career interventions. Rev. Psicol. IMED 2017, 9, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hughes, D.; Mann, A.; Barnes, S.; Baldauf, B.; McKeown, R. Career Education: International Literature Review. Warwick Institute for Employer Research and Education and Employers Research. 2016. Available online: https://www.educationandemployers.org/research/careers-education-international-literature-review/ (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Langher, V.; Nannini, V.; Caputo, A. What do university or graduate students need to make the cut? A meta-analysis on career intervention effectiveness. J. Educ. Cult. Psychol. Stud. 2018, 17, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiston, S.C.; Li, Y.; Goodrich Mitts, N.; Wright, L. Effectiveness of career choice interventions: A meta-analytic replication and extension. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Crowley, S.; Lee, Y. A Scoping Review of Technology-Based Vocational Interventions for Individuals with Autism. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 2022, 45, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, S. Career HOPES: An Internet-delivered career development intervention. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2010, 23, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pordelan, N.; Sadeghi, A.; Abedi, M.R.; Kaedi, M. How online career counseling changes career development: A life design paradigm. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2018, 23, 2655–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thul-Sigler, A.; Colozzi, E.A. Using Values-Based Webinar Interventions to Facilitate Career-Life Exploration and Planning. Career Dev. Q. 2019, 67, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M.; Stebleton, M.J. Another Story to Tell: Outcomes of a Single Session Narrative Approach, Blended with Technology. Can. J. Career Dev. 2020, 19, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, T.S.; Pereira, M.A. Avaliação dos efeitos do Minha História de Carreira para construção de carreira. Rev. Bras. Orientac. Prof. 2020, 21, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pordelan, N.; Hosseinian, S. Design and development of the online career counselling: A tool for better career decision-making. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 41, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pordelan, N.; Hosseinian, S. Online career counseling success: The role of hardiness and psychological capital. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2021, 21, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serbanescu, L.; Ciuchi, O. Digital counseling and guidance of students—Real and effective support during the pandemic periods. Rev. Cercet. Interv. Soc. 2021, 75, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardi, Z.; Eseadi, C.; Guspriadi, Y. A web-based career counseling intervention for enhancing career decision-making among prospective polytechnic students. Online Submiss. 2022, 12, 682–689. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, L.; Mourão, L.; Pinto, C. Career counseling for college students: Assessment of an online and group intervention. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 140, 103820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, S.; Ginevra, M.C.; Di Maggio, I.; Soresi, S.; Nota, L. In the same boat? An online group career counseling with a group of young adults in the time of COVID-19. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2022, 22, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camussi, E.; Meneghetti, D.; Sbarra, M.L.; Rella, R.; Grigis, P.; Annovazzi, C. What future are you talking about? Efficacy of Life Design Psy-Lab, as career guidance intervention, to support university students’ needs during COVID-19 emergency. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1023738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünder, Ü.; Çavus, M.; Munusturlar, M.; Akdogan, E.; Görkem, S.; Öztürk, E.; Balkan, S.; Banar, M. The Effects of “Transition to Professional Life’’ Course on Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy. Yükseköğretim Derg. 2023, 13, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammitti, A.; Russo, A.; Ginevra, M.C.; Magnano, P. “Imagine Your Career after the COVID-19 Pandemic”: An Online Group Career Counseling Training for University Students. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osipow, S.; Carney, C.; Barak, A. A scale of educational-vocational undecidedness: A typological approach. J. Vocat. Behav. 1976, 9, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.K. Measuring a three-dimensional construct of career indecision among college students: A revision of the Vocational Decision Scale: The Career Decision Profile. J. Couns. Psychol. 1989, 36, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.A.P. Desenvolvimento de carreira em universitários: Construção de um instrumento. In Proceedings of the Anais do III Congresso Brasileiro Psicologia Ciência e Profissão, São Paulo, Brazil, 3–7 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ulaş, Ö.; Yıldırım, İ. The development of career decision-making self-efficacy scale. Turk. PCG-Assoc. 2016, 6, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gati, I.; Krausz, M.; Osipow, S.H. A taxonomy of difficulties in career decision-making. J. Couns. Psychol. 1996, 43, 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, N.E.; Luzzo, D.A. Career Assessment and the Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy Scale. J. Career Assess. 1996, 4, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfeli, E.; Lee, B.; Vondracek, F.; Weigold, I. A multi-dimensional measure of vocational identity status. J. Adolesc. 2011, 34, 853–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savickas, M.; Porfeli, E. Revision of the Career Maturity Inventory: The Adaptability Form. J. Career Assess. 2011, 19, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audibert, A.; Teixeira, M. Career adapt-abilities scale: Evidences of validity in Brazilian university students. Rev. Bras. Orientac. Prof. 2015, 16, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M.; Porfeli, E. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soresi, S.; Nota, L.; Ferrari, L. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale-Italian Form: Psychometric properties and relationships to breadth of interests, quality of life, and perceived barriers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maggio, I.; Ginevra, M.; Nota, L.; Soresi, S. Development and validation of an instrument to assess future orientation and resilience in adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2016, 51, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, S.; Di Maggio, I.; Ginevra, M.C.; Nota, L.; Soresi, S. ‘Looking to the Future and the University in an Inclusive and Sustainable Way’: A Career Intervention for High School Students. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, P.J. The career construction interview. In Career Assessment: Qualitative Approaches; McMahon, M., Watson, M., Eds.; Brill: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Nota, L.; Soresi, S.; Di Maggio, I.; Santilli, S.; Ginevra, M.C. Sustainable Development. In Career Counselling and Career Education; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Santilli, S.; Ginevra, M.C.; Sgaramella, T.M.; Nota, L.; Ferrari, L.; Soresi, S. Design my future: An instrument to assess future orientation and resilience. J. Career Assess. 2017, 25, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginevra, M.C.; Sgaramella, T.M.; Ferrari, L.; Nota, L.; Santilli, S.; Soresi, S. Visions about future: A new scale assessing optimism, pessimism, and hope in adolescents. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2016, 17, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumboltz, J.D.; Thoresen, C.E. The effect of behavioral counseling in group and individual settings on information-seeking behavior. J. Couns. Psychol. 1964, 11, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zener, T.B.; Schnuelle, L. Effects of the Self-Directed Search on high school students. J. Couns. Psychol. 1976, 23, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasel, K.; Besharat, M. Relationship of perfectionism and hardiness to stress-induced physiological responses. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Golparvar, M.; Jafari, M. Prediction of psychological capital through components of spirituality among nurses. Iran. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2013, 1, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Stumpf, S.A.; Colarelli, S.M.; Hartmann, K. Development of the Career Exploration Survey (CES). J. Vocat. Behav. 1983, 22, 191–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaSilveira, A.; DeCastro, T.; Gomes, W. Escala de Autorreflexão e Insight: Nova Medida de Autoconsciência Adaptada e Validada para Adultos Brasileiros. Psico 2012, 43, 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Mourão, L.; Tavares, S.; Sandall, H. Professional development short scale: Measurement invariance, stability, and validity in Brazil and Angola. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 841768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peixoto, A.L.A.; Janissek, J.; Aguiar, C.V.N. Autopercepção de Empregabilidade. In Ferramentas de Diagnóstico para Organizações e Trabalho: Um olhar a Partir da Psicologia; Puente-Palacios, K., Peixoto, A.L.A., Eds.; Artmed Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2015; pp. 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins-Yel, K.G.; Gumbiner, L.M.; Grimes, J.L.; Li, P.J. Advancing social justice training through a difficult dialogue initiative: Reflections from facilitators and participants. J. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 48, 852–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginevra, M.C.; Santilli, S.; Di Maggio, I.; Nota, L.; Soresi, S. Development and validation of visions about future in early adolescence. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2020, 48, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, A.; Starcevic, V.; Giardina, A.; Khazaal, Y.; Billieux, J. Multidimensional Assessment of COVID-19-Related Fears (MAC-RF): A Theory-Based Instrument for the Assessment of Clinically Relevant Fears During Pandemics. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craparo, G.; Magnano, P.; Paolillo, A.; Costantino, V. The Subjective Risk Intelligence Scale. The Development of a NewScale to Measure a New Construct. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 966–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized Self-Efficacy scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A user’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs; Weinman, J., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; NFER-NELSON: Windsor, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nuovo, S.; Magnano, P. Competenze Trasversali e Scelte Formative. Strumenti Per Valutare Metacognizione, Motivazione, Interessi e Abilità Sociali Per la Continuità Tra Livelli Scolastici; Edizioni Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).