Abstract

The failure of the democratic movement during 2014–2020 prompted tens of thousands of Hongkongers (~40,000) to reluctantly leave their hometown and migrate to Taiwan to seek a freer future. Taiwan’s cultural similarity to Hong Kong, together with Taiwan’s democracy and geographic proximity, are commonly recognized as pull factors of migration. However, the intensifying cross-strait tensions since late 2021 have witnessed Taipei tighten its approval of Hongkongers’ applications for permanent residency mainly in fear of the infiltration of Chinese agents. Based on mixed-methods in-depth interviews (N = 15) and an online survey (N = 147) with Hong Kong migrants, this paper reveals their complex experience in adapting to the Taiwan way of life, becoming frustrated by Taipei’s attitudinal change, and contemplating onward migration. The findings reveal underlying cultural differences between Hong Kong and Taiwanese societies—manifesting as a cultural conflict—amid fears of an encroaching communist China.

1. Introduction

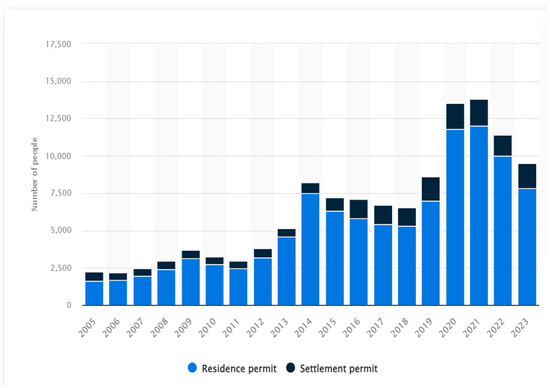

Taiwan is a self-governed island with a population of more than 23 million ethnic Chinese. Geographically, Taiwan is adjacent to Hong Kong. The two places share the same time zone and are separated by only about 1.5 h flying time. Economically, Hong Kong, a well-known Asian financial hub, has outperformed Taiwan in many aspects. For example, in 2023, Hong Kong—with a population of about 7 million ethnic Chinese—has a GDP per capita of USD 51,608 compared to Taiwan’s USD 32,687, and the GDP per capita of Hong Kong was on average over 40 percent higher than that of Taiwan during 2014–2023. From 2005 to 2013, the average annual number of Hongkongers applying for immigrant status in Taiwan (in terms of the number of “residence permits” granted) was 2640 (this figure is a proxy as it includes a negligibly small number of migrants from Macau; see https://www.statista.com/statistics/1087016/taiwan-number-of-immigrants-from-hong-kong-and-macau/; last accessed on 6 September 2024). It is commonly believed that the Taiwan-bound migration before 2014 was mainly driven by Taiwan’s geographic proximity and cultural similarity (e.g., weather, food, language, etc.) to Hong Kong, and Hongkongers could take advantage of the lower cost of living and slower pace of life due to Taiwan’s relatively less economic vibrancy [1,2]. However, from 2014 to 2022, the annual average number of Hongkongers applying for migration to Taiwan surged nearly triple to 7504 (see the trend in Figure 1), most of whom were believed to appeal to another feature of Taiwan—democracy.

Figure 1.

Taiwan Government Granting Residence Permits and Citizenship (“settlement permits”) to Hongkongers, 2005–2023 (source: Statista.com (see https://www.statista.com/statistics/1087016/taiwan-number-of-immigrants-from-hong-kong-and-macau/; last accessed on 6 September 2024)).

The surge in migration can be traced back to 2014 when the civil disobedience movement of Occupy Central broke out in Hong Kong. Also known as the Umbrella Movement, the event called for hundreds of thousands of protestors to block roads in the city’s financial district in an attempt to paralyze its activities and pressure the Chinese government to offer Hong Kong genuine democracy, characterized by free and fair elections, rather than a system where candidates are limited to those endorsed by Beijing.

Taking place between 26 September and 15 December, the social movement ended in failure with police clearance [3]. However, Hongkongers’ unresolved demand for freedom and universal suffrage was re-ignited five years later when the government proposed to amend its extradition law. Had the legislature passed the amendment bill on 12 June 2019, Hongkongers feared that any dissent against Beijing would constitute a legitimate cause for being extradited to the mainland and subjected to its flawed legal system. Fighting for the autonomy, democracy, and the rule of law once promised by Beijing, from June 2019, 1–2 million Hongkongers became involved in street protests. The movement turned out to be a more massive and violent extension of the Umbrella Movement [4]. The tension between the protestors and the government remained in early 2020, but the size of rallies and protests dwindled partly due to the increasingly violent police suppression and partly due to the COVID-19 crisis outbreak. Considering the protests in Hong Kong as a national threat, Beijing announced on 21 May 2020, the promulgation of the National Security Law (NSL) in Hong Kong. The NSL, which is supposed to sanction crimes of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces, is widely considered by the Western media to be Beijing’s political weapon to suppress political dissidents and jeopardize the freedom of Hong Kong [5]. In the face of Beijing’s complete takeover, many Hongkongers decided to express their disapproval using their feet. Days after the content of the NSL was released in May 2020, big data revealed that Internet keyword searches related to “migration” surged fourfold, and the number of inquiries to migration consultants increased tenfold [6]. Three months later, an online survey found that over three-fourths (76%) of the respondents (N = 2580) expressed a desire to emigrate after the NSL became effective at 11 p.m. on 30 June [7]. In this survey, the most popular destination for relocation was Taiwan (32%), followed by the United Kingdom (23%). One forecast suggested that total emigration from Hong Kong due to the promulgation of NSL would eventually reach 1.2 million people, or 16 percent of the population [8]. (The majority will actually leave for the UK because in January 2021, the British government offered citizens of its former colony an easy emigration pathway, and within two years, over 140,000 Hongkongers had been granted entry into the UK.)

To the Taiwan government led by Tsai Ing-wen during 2016–2024 (in January 2024, Lai Ching-te won the presidency of Taiwan and assumed leadership in late March. Lai is a member of the Democratic Progressive Party, the same political party as his predecessor, Tsai Ing-wen), the surge of immigrants from Hong Kong after the social movement in 2019 meant more than simply an immigrant influx. Hong Kong’s 2019 movement has arguably played the role of game-changer in Taiwan’s presidential election in January 2020. The fact was that since 2018, the incumbent president Tsai and her political party had received low public support after the party’s failure in local elections. In a major speech to “Taiwanese compatriots” in early 2019, Xi Jinping—leader of communist China—called for the “One Country, Two Systems” way of unification akin to Hong Kong, and asserted that Beijing would not “promise to renounce the use of [military] force” to realize the unification [9,10]. Tsai immediately rejected Xi’s call. As the social movement in Hong Kong broke out in mid-2019, the slogans of “Today Hong Kong, Tomorrow Taiwan” and “Standing with Hong Kong” permeated Tsai’s presidential election campaign [10]. Months later, Tsai won her second term with 57 percent of the vote in a record-high turnout presidential election (75%). With this background, Tsai’s government set up a special office in July 2020 to take care of the livelihood of some 100 young Hongkongers who were involved in the 2019 protests and found sanctuary in Taiwan [10]. With signs of sympathy expressed by the Tsai administration, since 2014, Hongkongers have been applying for Taiwan-bound migration, with the number of applicants surging from 5858 in 2019 to 11,173 in 2021. We estimate that about 40,000 Hongkongers have actually taken action to move to Taiwan since 2014. (The figure is only an estimate as no official figure can be found. We assume that among the total number of 67,538 migration applicants during 2014–2022, only a slight majority (60%) actually took up the option of migration. And, among these 40,523 migrants, the majority migrated in the second half of 2021 when there were spells of free travel between Hong Kong and Taiwan amid the attack of COVID-19 pandemic during 2020–2022. These assumptions are generally in alignment with the narratives of the informants interviewed in the present study. Our estimation also takes into account a report that suggests that more than 27,000—including entrepreneurs, professionals, and students, as well as activists—came to Taiwan on temporary visas during 2019–2021 [11].) Most were investor immigrants who were asked to invest at least NTD 6 million (~USD 200,000) to run a local business. Three years later, they could apply for permanent residency. The approval of Hongkongers’ applications for the “settlement permit” was said to be a simple straightforward formality. However, it began to change abruptly approaching the end of 2021 when the vast majority of applications were reported to have been held up by Taipei, with applicants being told to supply extra documents and wait for further months or even another year, pending further inquiries.

Evidently, this unforeseen change was caused by simmering cross-strait tensions. Taiwan, which is merely 128 km away from mainland China, has indeed never escaped from the threat of Beijing’s military takeover since the Kuomintang government of the Republic of China and their supporters—about 1.5 million people—fled to Taiwan in 1949. The exile was the result of the civil war that broke out in China in 1945, with the Chinese Communist Party claiming sovereignty over the mainland and renaming the country the People’s Republic of China. Although Tsai’s administration claims that Taiwan has never been part of the People’s Republic of China, Beijing proclaims that Taiwan is, has been, and should be under its sovereignty. With this historical background, several crises had broken out in the Taiwan Strait (for example, after Taiwan announced its plans to hold its first democratic presidential elections in 1995, Beijing flexed its military muscle with months of military drills, including firing missiles 35 miles from Taiwan’s ports [12].) The most recent and relevant to the present study was the crisis of August 2022. At that time, in order to protest against the visit of U.S. House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan that—from the view of Beijing—symbolized the US’s recognition of Taiwan’s independent sovereignty, Beijing launched large-scale military exercises following the visit. With the increasing military threat, Taiwan officials openly expressed that the influx of Hong Kong immigrants could mean the infiltration of Chinese agents that would jeopardize Taiwan’s national security [13]. Such fears were not purely irrational phobias to the populace of Taiwan. The quintessential example was Xie Xizhang who had presented himself as a Hong Kong businessman on visits to Taiwan before he stood accused in 2021 of helping Beijing recruit spies from Taiwan’s military leaders [14].

Other reasons in relation to the sudden rise in the threshold for Hongkongers to settle include the malpractice of some investor migrants faking the operation records of their businesses, and the xenophobic attitude of local Taiwanese in witnessing so many Hong Kong immigrants residing on the island within a short timeframe [15,16]. For example, in April 2022, Chiu Chui-cheng, Deputy Minister of the Mainland Affairs Council of Taiwan, pointed out the problematic situation surrounding applications for residency and settlement by Hong Kong migrants. He noted that some immigration companies engage in fraudulent practices, with many Hongkongers exploiting loopholes by presenting themselves as “genuine immigrants” while participating in fake investments [17]. This means that after obtaining residency qualifications, these individuals often withdraw their investments or even return to live in Hong Kong, with reports indicating that the withdrawal rate has reached approximately 90%. In response, the Taiwan authorities strengthened its review process as early as the beginning of 2020. This included extending the required investment operation period in Taiwan from one year to three years and introducing new conditions, such as the necessity to employ two or more Taiwanese staff and to maintain a physical office space.

Against this backdrop, more than ten thousand Hongkongers have seen their applications for permanent residency stalled by Taipei. This paper aims to capture their views and actions to take in their citizenship quests amid intensifying cross-strait tension. Based on mixed-methods in-depth interviews (N = 15) and an online survey (N = 147) with Hong Kong migrants, the findings aim to explore the actors’ complex experience in adapting to the Taiwan way of life, becoming frustrated by Taipei’s attitudinal change, and contemplating onward migration. It is not the main purpose of the present study, however, to generalize the findings from this non-random sampled study to all Hong Kong migrants in Taiwan. Rather, our goal is to unravel, based on the qualitative narratives and statistical patterns expressed by the informants, the hidden cultural differences between Hong Kong and Taiwan societies—which have ostensibly become cultural conflict—in the face of political uncertainties.

Before proceeding, it is essential to establish the academic and theoretical significance of examining the emotional experiences of Hong Kong migrants in relation to state authorities within the context of migration studies. The following Section will explore key theories and concepts that underpin this investigation.

2. Emotional Reactions of Hong Kong Immigrants Toward State Authorities

To conceptualize Hongkongers’ migration to Taiwan is not a straightforward task. The migrants certainly exhibit certain features of “voluntary migrants” whose migration decision is made by an individual’s free will and initiative against choices with explicit costs and benefits calculable to the actor [18,19,20]. More specifically, they resemble what are known as “lifestyle migrants” who choose to relocate to another place with a better work-life balance, a higher degree of freedom, and with more interesting leisure activities [21]. However, the Hongkongers in question also entail some features of a political diaspora who belong to the category of “forced migration” in the literature. “Forced migrants”, according to Mooney, refer to those who are unwillingly “uprooted from their homes and property, separated from their community and often severed from family support networks, and cut off from their resource base” because of “armed conflict, internal strife, and communal tensions” [22]. However, in the context of Hong Kong, the forcefulness of the political repression behind the emigration drive is not strong. As reconfirmed in our fieldwork and literature search, the political threats that most migrants face—except for a couple hundred of those who were deeply involved in the 2019 protests—are not imminent. Beijing has also issued reassurances that Hong Kong’s way of life would be maintained and its firmer control over the territory would not adversely affect the vast majority of people who abided by the law (in May 2020, Beijing argued that the implementation of the NSL was to “protect the vast majority of the Hong Kong people who abide by law. This meets the fundamental interests of Hong Kong society.” [23]). Likely to stay unharmed by the vibrant economy, what made so many Hongkongers choose to move to a new place in Taiwan, the UK, or elsewhere? Here, we find it makes sense to term Hong Kong migrants as “reluctant migrants”.

In the literature, “reluctant migration” has only been elusively defined as being positioned somewhere between being “voluntary” and “forced”. It generally refers to a form of migration in which people are not forced to move; indeed, they would have preferred to stay should there be no unfavorable situation at their current location [19,20,24]. The most widely quoted example of reluctant migration refers to the massive exodus of Cubans—fearing the Fidel Castro-led communist government—who legally and illegally entered the US following the 1959 Cuban revolution. Other uses of the concept of “reluctant migration” have been ambiguously mixed with “environmental migration”, which is nature-forced (e.g., Louisiana residents relocating elsewhere following Hurricane Katrina [19]), or overlapped with “economic migration”, which is nature-voluntary (e.g., people moving out of agriculture and into industry associated with rural-to-urban population transfers in India [25], Italy [26], and Mexico [24]). (One should note that some scholars have recently expressed their dissatisfaction over the rigid, dichotomized, voluntary–forced migration typology. For example, Bakewell argues that the conceptual boundaries between forced and voluntary migration are “inherently blurred and questions their analytical value” [27]. Erda and Oeppen suggest voluntary and forced migration as a “continuum of experience, not a dichotomy” [28]. Piguet complains that the dichotomized terminology has failed to characterize emerging modes of migration, such as temporary migration [29]. In one way or another, these scholars deem that the voluntary–forced conceptual duo is problematic mainly because of the political impacts (e.g., levels of compensation, services provided, etc.) on the migrants per se due to different labeling. Here, this paper possesses the objective of elucidating the concept of “reluctant migration”, which carries certain meaningful, theorized links with voluntary and forced migration.)

To avoid the abovementioned conceptual confusion, we suggest that “reluctant migration” is defined as a form of migration in which the move is mainly triggered by people’s cultural drive to maintain their original way of life. To them, the indigenous mode of living is poised to erode due to certain imminent political and/or economic changes. While these changes do not bring about severe resource deprivation, looming political prosecution, or threats to life, they arouse a strong emotion of fear among actors about the long-term well-being and sustainability of themselves and their families. Therefore, unlike voluntary migrants, reluctant migrants’ cost–benefit evaluations are not necessarily “rational” in the sense that they attend less to the short-to-mid-term economic and well-being damage incurred in the migration. And, unlike forced migrants, the reluctant actors possess more complicated feelings about their native place and the identity they attach to it, as to “return home” is indeed always feasible both in the present and future.

One should note that migration due to the fear of losing one’s accustomed way of life is a déjà vu phenomenon in Hong Kong. It happened several decades ago when the city was transiting toward the change of sovereignty from neo-liberal Britain to communist China in 1997. From the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, an outbound migration wave was formed that carried away hundreds of thousands of Hongkongers who feared the forthcoming communist regime. Sussman estimates that emigration due to Hongkonger’s fear of 1997 was 800,000 (~13% of the population) with the vast majority (over 80%) leaving for Canada, Australia, or the US [30]. Many emigrants, however, steadily returned with newly acquired foreign citizenship as they felt that the handover brought about no calamitous change to Hongkonger’s original way of life. Sussman estimates the number of post-handover re-migrants to be “500,000, that is, 83% of those who migrated and nearly 7% of the total population of Hong Kong” [30]. Whether the massive return of Hong Kong emigrants will repeat itself is unknown. However, what we endeavor to argue here is that Hongkongers who decided to start new lives in other places since 2014—including those in Taiwan—are more appropriately conceptualized as reluctant migrants. Their move is driven mainly by the fear of losing their original way of life, rather than the pursuit of higher economic returns, or the avoidance of immediate political repression.

So said, the migration of reluctant Hongkongers is not primarily driven by economic motivations or immediate threats of persecution. Given the feasibility of return, these migrants are also appropriately characterized as “transnationals” rather than traditional emigrants [31]. Unlike the conventional view of migrants seeking a new “home”, transnationals are seen as individuals who cultivate networks, connections, and activities across multiple contexts [32]. This conceptual shift places the construction of belonging and emotional ties to both the country of origin and destination at the center of migration studies. The current focus on Hong Kong migrants’ negative emotions (e.g., disappointment) toward the Taiwan authorities is thus not merely an ad hoc study in a specific context; it represents an important concern regarding the affective turn in migration studies since the 1990s. Unlike the traditional image of the migrant, the “success” of migration is not defined solely by economic incentives and instrumental rationalities or by identity integration with locals. Rather, it is more concerned with the actors’ emotional attachments and sense of belonging [33]. The feelings of uncertainty and even betrayal by the Taiwan government, particularly in light of tightened policies on permanent residency approval, clearly evoke an emotional response that prompts these actors to question fundamentally the validity of their migration decision.

In addition to its alignment with the growing literature on emotional transnationalism, the present research echoes studies on migrants’ mistrust of local state officials, which results in varied responses based on the Exit, Voice, Loyalty, and Neglect model [34]. It also enriches previous studies on local residents’ resentment toward migrants due to increasing numbers [35] and perceived threats to the cultural identity of locals [36]. Furthermore, this investigation contributes to the emerging body of research on anti-migrant sentiment in Western developed countries [37,38,39].

3. Data and Methods

Our findings are mainly based on an empirical study using a mixed method of qualitative and quantitative approaches. Since not much is known about Hong Kong migrants’ experience of the sudden attitudinal change of the Taiwan authorities since late 2021, we began with a series of loosely semi-structured, face-to-face in-depth interviews via Zoom with a sample of 15 Hongkongers living in Taiwan. All recruitment and interview procedures were conducted between June and November 2022. All interviews were conducted by the first author. All the interviewees migrated through the investment scheme and were living in more economically vibrant northern parts of Taiwan, including Taipei, New Taipei City, and Taoyuan. The guiding questions of the interview included “What were the factors that made you decide to leave Hong Kong and come to Taiwan?”, “What are the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ things you and your family members have experienced after relocating to Taiwan?”, “Do you agree that the Taiwan government has changed/tightened their way to approve Hongkongers’ applications for permanent residency? If their reply was positive (which all interviewees’ replies actually were), what are your opinions?”. Although the number of interviewees invited to participate in this study was small, the range of the informants involved was relatively diverse. Their ages ranged from 25 to 49 years. There was a fair balance in gender among the informants (female = 6, male = 9). At the time of the interview, the informants had been living in Taiwan for between 14 and 37 months (see Table 1). All these reflect our effort to take into account a mix of potentially different perspectives on the research subject.

Table 1.

The Profile of the Interviewees.

After the interviews, their narratives were transcribed and subjected to thematic analysis. The two authors individually went through all the interview transcripts, identified the themes, and, if needed, debated between themselves on the articulation of the themes. Consequently, the contents of the narratives were summarized and arranged under three main themes: (i) Taiwan’s versus Hong Kong’s way of life, (ii) the rule-of-man versus rule-of-law, and (iii) to stay versus to leave. We believe that these themes are the most relevant and accurate representations of the complex, emotion-related experiences expressed by the informants.

Apart from the thematic analysis, the interview transcripts also contributed to the construction of part of the questionnaire that was used to capture the collective patterns of Hong Kong migrants in Taiwan. The most constructed were the answer options of two questions used in the survey. The first question was “To what extent do you agree that raising the threshold for Hong Kong migrants to settle in Taiwan is reasonable?” For those who chose “strongly agree/agree” out of the five-point Likert options, they were asked to indicate the reason(s) behind them. Informed by the interviews, the answer options included the following: it is reasonable as it (i) blocks entries of Chinese agents; (ii) reflects some bad past examples of Hong Kong immigrants who either left Taiwan, or closed down their business, shortly after obtaining permanent residency; and (iii) rejects those applications in which the Hongkongers fake business operation records. The second question—which is meant to be analogous to the first one—stated “To what extent do you agree that raising the threshold for Hong Kong migrants to settle in Taiwan is unreasonable?” For those who chose “strongly agree/agree”, they were asked to indicate their reason(s) behind which included the following: it is unreasonable as it (i) delays in the applications that have already fulfilled all stipulated requirements; (ii) reflects the Taiwan authorities’ mistrust of Hongkongers as a whole based on political grounds; (iii) is akin to forfeiting Hongkongers’ right to leave Taiwan, or close down their business after obtaining Taiwan citizenship; and (iv) suggests that the Taiwan authorities only want to take Hongkongers as a means to do business without the intention to grant them citizenship in return.

The survey was posted to two Facebook groups mainly consisting of Hong Kong migrants in Taiwan. Each group was composed of around 150 Facebook accounts. The questionnaire was an anonymous one, which welcomed participation only to those Hongkongers who had migrated to Taiwan through the investment/professional scheme since 2014. The survey was open from January to April 2023. The questionnaire contained 14 questions. Apart from the two key questions mentioned just before, and several questions on demographic information and current migration status of the respondents, other questions included the following: (i) “To what extent are you confident in obtaining permanent residency after the period of stay as stipulated by the Taiwan authorities?”; (ii) “How probable that you leave Taiwan now without obtaining the permanent residency?”; (iii) “How probable that you will leave Taiwan when you fail to obtain the permanent residency in the next round of application?”; and (iv) “If you are to leave Taiwan, most likely, what is your next destination?” By the time the survey was closed, 147 responses were obtained. One should note that the samples were biased toward those who migrated via the investment scheme (85.7%) and had not yet obtained the “settlement permit” (91.8%). The selected profile of the respondents is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The Selected Profile of the Respondents.

Our analysis and interpretation of the interviewees’ narratives in the forthcoming Sections will be presented under three themes. When appropriate, these qualitative findings will be supplemented by the survey data.

4. Findings

4.1. Taiwan’s Versus Hong Kong’s Way of Life

In Taiwan, it is very important to tell stories [of good people]. […] It is a must that the readers feel that the [author’s] intention is good and the feeling is genuine. Even if you are involved in a car accident, a story like having a pregnant woman onboard can get someone out of legal responsibility. It can never happen in Hong Kong. (Donald)

The 15 participants were obtained from snowball sampling that was conducted across six months in 2022. During this period, more and more news about Hong Kong migrants’ unsuccessful applications for permanent residency appeared on the Internet and social media. This news possessed explicit negative impacts on the mood of the informants when describing their post-migration lives in Taiwan. It means that, as the fieldwork journey transpired, the informants tended to highlight more the difficulties they encountered—rather than joy—in adapting to the Taiwan way of life. In particular, those who were interviewed near the end of the fieldwork period usually took proactive moves to pinpoint some commonly rosy features of Taiwanese society that many Hongkongers misconceived. For example, both Kaleb and Lennon said that the cost of living in Taiwan was lower than Hong Kong only for modest consumption, such as the fast food sold in street stores. For upmarket consumption, such as having a proper dinner in a decent restaurant, the cost equaled or was even higher than in Hong Kong. Hilary and Mandy both suggested that it was erroneous to eulogize Taiwan’s healthcare system, which had been portrayed widely as good and inexpensive in the media. They elaborated that the service would be good only to those who used it frequently. Since the service required all actors to pay a monthly fee (~NTD 2000) regardless of the level of consumption, those who were in sound health and seldom used the service were actually disadvantaged. They unanimously rebuked the common conception among Hongkongers that Taiwan’s healthcare service was inexpensive, or even “free”. To the two informants, the service was equivalent to purchasing a medical insurance package akin to what some did in Hong Kong. Moreover, Donald, Gigi, and Nancy hinted that the Taiwanese were far less politically sympathetic to Hongkongers than many Hongkongers had thought.

Having said that, all the informants did mention some everyday life examples of how their lives in Taiwan had aligned with their general positive preconceptions of Taiwan before migration. For example, the lower cost of living in Taiwan was usually interpreted as enjoying cheaper rent and more spacious homes than in Hong Kong. The geographical proximity was commonly understood as having no time difference with relatives and friends in Hong Kong, which made real-time video chats a convenient way to maintain relationships in their hometown. The cultural similarity was often translated in terms of having similar weather, food, and language. All these constituted the enhancing elements for the informants seeking their new lives in Taiwan. Among their narratives on livelihood, the cultural dimension was emphasized with the articulations usually revolving around two popular qualities of living in Taiwan, namely: low-stress living and the “human touch”. More importantly, these two qualities were usually seen as a mixed blessing such that the informants usually cherished them, but at the same time, found them at odds with their accustomed way of life in Hong Kong.

The low-stress living was typically translated as “slow-living” (manhuo) or “balanced” (pingheng) living during the interviews. For example, the informants expressed huge joy in having more opportunities to explore the natural environment, and more quality time with their spouse and kids, when compared with the competitive and fast-paced living in Hong Kong. These positive experiences apart, the low-stress living in Taiwan possessed its downside. Since all the informants were to operate their own businesses, they needed to deal frequently with a wide range of local people, including builders, bankers, accountants, and government officials. The low-stress-living was often interpreted by the informants as sluggishness and inefficiency in the Taiwan way of doing business. The most commonly heard issues came from the informants’ experiences with banks, for example,

I spend like more than two hours doing one thing in the bank. […] They seem to be able to do only one task a day. For the same thing, I need only two hours to complete in Hong Kong. But, here, it normally takes weeks. (Clark)

I don’t know whether my experience is unique or not. Every time—I mean every time—I spent like hours doing something in the bank. And, when I was in my car driving away, the bank called me and said that they had missed something and requested me very politely to return. (Bowie)

For one informant who told his builder what to do with his café that was opening very soon, the builder was surprised to say “Why do you Hongkongers do so many tasks at the same time, and drive the progress so hurriedly? Why not take more time?” Many informants said that the Taiwanese simply did not understand what Hongkongers meant by agility, flexibility, and efficiency, which led to more achievements and higher economic returns.

The term “human touch” (renqingweir, literally, the “flavor of human feelings”) refers to a quality of humanity that involves the courtesy, caring, and generosity that people exhibit in treating others. It is a popular discourse bred among Hongkongers to describe the Taiwanese populace as kind-hearted people, whereas Hongkongers deem themselves to be ruder, meaner, and more calculative in interpersonal relationships. During the interviews, all informants expressed different degrees of appreciation of the “human touch” that they had experienced when interacting with the Taiwanese, and could at least quote one first-hand experience in support of their positive feelings. For example:

I was asking my landlord where I could rent a car for sightseeing. He then lent me his Mercedes to drive all over Taiwan for two weeks. It was a real [pleasant] surprise! (Isaac)

When I first came [to Taiwan], I was busy doing business. One of my neighbors unexpectedly sent us lunch they just made. I was so moved! (Freda)

While “human touch” is a positive cultural quality, it also means that people’s judgment on things is largely hinged upon their feelings about the intention of that specific person, rather than the general principles stipulated in objective terms, or even laws. The verbatim quote at the head of this Section represented an example suggesting how “good intentions” could avoid legal sanction after a car accident. Another example involved the political election in Taiwan:

In Taiwan, a person who has been legally charged with corruption and is about to go to jail can win a legislature election! They [i.e., the voters] all know that the candidate did commit the offense and will surely go to jail. … The Taiwanese will support that kind of politician if they can offer touching stories. (Jason)

The informants generally make sense of the Taiwanese “human touch” in terms of their moral priority of emotion; then, reason, then, law (qing li fa) that guides their everyday life. What this means is that the Taiwanese usually make a strong appeal to the subjective emotion, they possess about (the intention of) specific people or specific things in guiding their attitude and action toward these people/things. Making a moral judgment on a person’s behavior or the nature of a phenomenon in terms of reasons or law is considered less important. Most informants admitted that Hong Kong’s way of doing things was exactly the opposite. They unanimously concurred that Hong Kong society appeals to law first, then reason, and lastly, emotion (fa li qing). The informants agreed that they had endeavored to appeal to the Taiwanese officials who regularly scrutinized their business in terms of the “human touch”. For example, even Manson believed that he had carried out everything right in operating his business according to the laws and regulations, and he admitted he would pay extra effort to impress the officials with the “human touch” in his written reports; he said:

I need to tell good stories, like working very hard till 2:00 am every day. … I need to show my love and passion for the Taiwanese and living in Taiwan because I am afraid that my application [for permanent residency] may not be approved. (Manson)

Understandably, Hongkongers who had been living in a fast-paced international financial hub would experience cultural shock in relocating to a laid-back island where interpersonal relationships are highly emphasized. From the narratives, such cultural differences did constitute some inconveniences to the Hong Kong migrants who had been looking forward to reconstructing their accustomed way of life in Taiwan that they feared losing in their home city. These inconveniences were said to be, to a great extent, bearable and could be overcome as time passed. However, when such inconveniences became obstacles for the informants to obtain permanent residency, what was originally deemed to be a cultural difference became a cultural conflict.

4.2. The Rule-of-Man Versus Rule-of-Law

The Taiwanese utterly do not understand Hongkongers. Most Hongkongers are not interested in infiltrating Taiwan. Anywhere people can earn money and have freedom are the key [migration] targets for us. (Kaleb)

In the survey, nearly 87.8 percent of respondents considered the government’s raising the threshold for Hong Kong migrants to settle in Taiwan unreasonable. However, 16.3 percent found it reasonable with 12.2 percent holding a mixed view such that they deemed the change both unreasonable and reasonable—for different reasons. When the dataset excluded 15 cases who reported either oneself, or his/her family members having obtained permanent residency, the proportion deeming the change unreasonable rose further to 90.9 percent, and those who deemed it reasonable and mixed dropped slightly to 13.6 percent and 11.3 percent, respectively. Among those who were yet able to obtain the settlement permit, two-thirds (65.9%) reported being “unconfident/completely unconfident” in eventually acquiring citizenship, whereas 11.4 percent reported the prospect as “half-half”. Only 22.7 percent expressed that they were “confident/completely confident” in their application. For those who found the situation unreasonable in the whole dataset, almost all (95.3%) supported their view by indicating that they had already fulfilled all stipulated requirements; 58.2 percent saw it as a reflection of the Taiwan authorities’ mistrust of Hongkongers as a whole based on political grounds; 55.8 percent deemed the change as akin to forfeiting Hongkongers’ right to leave Taiwan, or to close down their business after obtaining Taiwan citizenship; and 51.2 percent suggested that the Taiwan authorities only wanted to use Hongkongers as a means to do business without the intention to grant them citizenship in return. All these clearly reflect that the vast majority of the respondents found the raising of the approval threshold unreasonable on the grounds that they had already fulfilled all stipulated requirements for acquiring permanent residency.

The collective negative sentiment against the change based on the survey findings echoed the qualitative data. Except for three who had obtained permanent residency, all informants (12 out of 15) registered strong negative feelings, if not simply anger, toward the sudden tightening of the approval process. These informants expressed similar stories of how they had followed everything stated in “black and white” (baizhiheizi) in accordance with the relevant laws and regulations; however, they were told to supply documents that required the applicant to wait months or even a year—a typical example was the tax return proof for the next financial year. To the informants, to supply the document itself was never the bone of contention. What was problematic was that the officials offered no explanation such as what the applicants had done wrong, or something deviating from what had been stipulated. One of the interviewees who saw her approval delayed paid extra efforts to ask the Taiwanese official the reasons behind the delay, but it ultimately proved fruitless; she said:

I asked if there was something wrong with my business? They said ‘no’. I asked was it because I had been working in a public organization in Hong Kong before, and I am now welcomed on political grounds? They said that it was not necessarily the case. And, then I kept asking, and their reply was still the same. My case does not have a problem. So, after that, I increasingly believe that there was no reason [in my case]. They [i.e., the Taiwanese government] just changes their attitude. [So,] [t]hey just said no to all [applications]. (Gigi)

In one “delayed” case, the interviewee (Nancy) expressed that the Taiwanese official simply found fault in her application and accused her of not hiring two “fulltime” Taiwanese staff required. However, Nancy defended that she had complied with what had been stipulated as to hire “two Taiwanese staff” (liangming Taiwanji zhiyuan) in her company. But the official insisted that those two staff members had to be “fulltime” while the applicants only hired them part-time. Nancy argued that the term “staff” (zhiyuan) could be legally defined as “part-time” “half-time”, or “fulltime” even in Taiwan. She further lamented that if “fulltime” was the key, why was it not stated in “black and white” in the document in the first place? In the interview, she added that her case was not unique as she heard someone encountering the same problem on the Internet.

Feeling that they had fulfilled all stipulated requirements, the informants commonly described the Taiwan government very negatively as “moving the goalposts” (banlongmen), or “the same as the mainland” (gen dalu yiyang)”, which meant that the government took the liberty to change the criteria or rules of the immigration scheme while the Hongkongers were still in the middle of the migration process. Seeing many Hongkongers’ applications being held up unreasonably, the informants described their predicament as akin to prisoners suffering from “prolonged period of imprisonment” (jiajian). The use of discourse reflected the informants’ view that the Taiwanese government paid little respect to the rule of law. In fact, throughout the interviews, the informants often used the discourse of “rule-of-law” (fazhi)—which was commonly accepted as the core value of Hong Kong—in contrast against the “rule-of-man” (renzhi) to characterize what they had experienced not only with the Taiwanese officials, but also the Taiwan populace as well. On the lack of the spirit of “rule-of-law” in Taiwan society, Hilary was particularly furious about her landlord who simply disregarded the tenancy agreement of her office signed by both parties; she explained:

The Taiwanese do not find the ‘rule-of-law” very important. When I wanted an earlier termination of the tenancy of my office according to the contract terms, my landlord asked said that it was not possible. I said: ‘What!? I just did things based on the contract!” He said: ‘The contract is just for reference only.’ I was driven crazy! (Hilary)

While the informants generally considered the tightening of Hongkongers’ citizenship applications as a sign of disrespect of the “rule-of-law”, did they share the worries expressed by the Taiwan government about Hong Kong migrants? Among the 24 respondents (16.3%) who “agreed/strongly agreed” that the tightening was reasonable in the survey, the vast majority (N = 21) agreed that the move was to inhibit infiltration of Chinese agents, and reflected past examples of Hong Kong immigrants who either left Taiwan or closed down their business, shortly after obtaining permanent residency. Eighteen out of these twenty-four also agreed that the change was to reject those applications in which the Hongkongers enacted inappropriate business operations. During the interviews, all informants explicitly recognized at least one of the mentioned worries expressed by the Taiwan government. However, they believed that the Taiwan government should have paid more attention to formulating the immigration schemes in the first place; for example, those eligible for Taiwan citizenship should not be born in mainland China, or one needed to continue his/her business in Taiwan for a certain number of years after obtaining permanent residency. The authorities could also revise the laws and regulations for future Hong Kong migrants. But, to the disappointment of most informants, the Taiwan government adopted a delaying strategy indiscriminately to all current applicants—which they considered was a breach of the rule of law.

While the informants generally shared the worries of Taiwan society on Hong Kong migrants, they generally considered them overstatements. One of the ways they addressed the issue was to appeal to the apolitical disposition of Hong Kong migrants. On this point, what Kaleb said about agent infiltration at the head of this Section was the most quintessential. Regarding the accusations of Hong Kong migrants’ inappropriate business operations, Isaac’s response was also typical among the informants. He expressed that the problems mainly originated from the lack of thoughtfulness in formulating the investment immigration scheme rather than the bad intentions of the actors; he said:

It is you [i.e., the Taiwanese government] who set the rules of the game, and it was you who approved them [i.e., applications which had involved those inappropriate business operations]. The situation had nothing to do with the people involved. If the rules [and their loopholes] were set as such, why would not people [i.e., take advantage] in accordance with them? Why the people are to blame? It is outrageous! (Isaac)

4.3. To Stay Versus To Leave

Yes, I can still stay in Taiwan even if I am not granted permanent residency. They will not force me to leave. But, it’s not easy to find a normal job [like a Taiwan citizen] as long as I am on investment visa. […] But, running a [profit-making] business these days is very difficult, not to mention that the Taiwanese government imposes many restrictions on foreign companies. Then, how can I run a money-losing business forever without being able to find a job? (Jason)

Among the survey respondents who had not obtained permanent residency either for themselves or their family members, 80.0 percent expressed various degrees of inclination to leave Taiwan “now”, i.e., at the time they filled out the questionnaire (60.0% “probable/highly probable”; 20.0% “half-half”). Their will to leave Taiwan was found to be more determined should they find their application for permanent residency rejected in the forthcoming round of assessment (72.3% “probable/highly probable”; 11.1% “half-half”). The good majority (71.1%) reported the UK as their target of onward migration, followed by “back to Hong Kong” (13.3%), and “no idea” (8.9%). The remaining 6.7 percent stated either “Canada” or “Australia”.

The strongest push factor expressed by the interviewees that drove them to leave Taiwan was resources. What Jason said as cited at the head of this Section was a typical and succinct illustration of this factor. In short, the unexpected extension of running a money-losing business beyond three years was likely to bring one’s finances eventually to the point of collapse.

The next most mentioned push factor was the sentiment of betrayal and deception by the Taiwanese government. It was common to hear the informants use the terms such as “deceit” (shoupian), “fury” (fennu), and Taiwan being “the same as the mainland” to describe their negative feelings about the Taiwanese government. These sentiments were at odds with the migrants’ fear of communist China that drove them to resettle in Taiwan in the first place; for example, Olivia said:

To stay away from those problematic politics [imposed by China] constituted a key reason of migration. Now, I am forced to face the same kind of problems here. It is totally defeating the original purpose of emigration. (Olivia)

Similar to the survey findings, among the 10 interviewees who indicated the intention of onward migration, seven said the UK was their first, if not the only destination. The most commonly mentioned reasons included that the UK was a country where the people respected the rule of law, and the government was likely to keep its word and truly welcome Hongkongers.

Another push factor involved those informants with children. While the adults migrated for a green pasture for the children, it turned out that their children were held up in Taiwan without a proper identity. This was something that all parent informants whose applications were delayed (N = 6) found totally unbearable. These informants had a high opinion of the education system of the UK, which made it a desirable target of onward migration.

Among the 12 interviewees who had not obtained permanent residency, two (both were unmarried and without children) indicated explicitly their willingness to stay in Taiwan. Gigi admitted that she has “nowhere to go”; she said:

Hong Kong was used to be a really excellent place. I thought Taiwan could be another Hong Kong. But, now, such a view is impossible. I still struggle about where to go? I shall not return to Hong Kong unless I absolutely run out of options. I am really unwilling to return. I don’t like the UK. My friends ask me to go to Canada. I may go to Canada. But nothing is set yet. (Gigi)

To Hilary, she was asked to supply extra documents three times for her citizenship application. Seeing no hope that it would come through, she decided not to maintain her money-losing business and gave up waiting for the result. Instead, she applied for jobs at a number of international companies in Taiwan. Given her engineering background, she eventually obtained a job so that her stay in Taiwan became financially sustainable. But she said that her case was rare as it required the company to do lots of work to get her a work visa, and pay her at least double the amount of salary normally entitled by local Taiwanese. Having said that, she said she could not apply for permanent residency even after working for a period of time, say, five years. She explained that the Taiwanese government only gave citizenship to those who had received education before to allow people who were on work visas to apply for citizenship after five years. But, still, she chose to stay; she explained:

My parents who have migrated to the UK ask me to go there. But, I do not like the UK. I want to live in Taiwan. (Hilary)

5. Conclusions: Cultural Similarity Misunderstood

Whatever the Taiwanese government says is just an excuse. They just do not want to see so many Hongkongers come. […] I was so shocked to see this 180-degree change. […] I do, however, learn one thing from this. We [i.e., Hongkongers] were all along brought up in the British system. We believe in what is written in “black and white”. In Taiwan, the meaning of texts is very vague. And, different officials just interpret the texts as they wish. To Hongkongers, it is absolutely amazing! In the English [i.e., Western] world, you write what you mean. It is a cultural difference that we [i.e., Hongkongers] have not noticed before. (Jason)

The stories of Hong Kong migrants in Taiwan reflect a seldom-seen phenomenon of a group of reluctant migrants who were poised to enact onward migration due to the cultural differences the actors experienced in their first destination of migration. In the literature, the most relevant one is perhaps the case of North Korean immigrants—who fled the repressive regime and settled in South Korea—and took action to onward migrate to Australia with an explicit will to attain a more Westernized and internationalized habitus [40]. The key difference is that Hong Kong migrants in Taiwan—as we attempt to argue—are more accurately described as “reluctant” rather than “forced” migrants. They are not pressed to leave their home city in the face of imminent political sanction. They are also unlike many voluntary migrants who migrate for an economic upgrade. Instead, most Hong Kong migrants in Taiwan are mainly driven by the fear that the complete communist takeover would eventually radically change their original way of life. The geographical proximity of Taiwan, its freedom and democracy, and the cultural similarity—as the Hongkongers commonly perceive in the first place—have made Taiwan a popular place of emigration. However, the narratives of the post-migration experiences of the informants, which were supplemented by the survey data, have pointed to the cultural differences between Hong Kong and Taiwan society. Such cultural difference becomes a cultural conflict when it comes to the sudden holding up of Hong Kong migrants’ requests for permanent residency.

What has gone wrong? The Hong Kong migrants find their citizenship approval being delayed unreasonably as they have undertaken everything stipulated in the laws and regulations. However, the Taiwan authorities consider their change reasonable due to their fear of infiltration of Chinese agents as well as Hongkongers’ inappropriate business operations. To put such discrepant views in another way, we would like to reference a recent unpublished scholarly research report on the Taiwanese populace’s perception of Hong Kong migrants. Mainly consisting of local Taiwanese, the research team recommended that the Taiwan authorities should “revise [the pertinent laws and regulations] to provide both the civil servants and people from Hong Kong and Macau with sufficiently clear standards [for obtaining permanent residence] to follow” [16]. However, regarding the Hong Kong migrants covered in the present study, they generally deem that the current “standards” have been “sufficiently clear”. The problem is just that the Taiwan authorities have added in factors outside these “standards”. What is important to Hongkongers is not to revise the current laws and regulations that will serve future migration applicants, rather they are deeply concerned about those who are currently in Taiwan and have followed the current rules and regulations. Seemingly, the two societies have talked past each other without a meeting point. The moot question is, while both societies share the same political fear factor of Beijing’s takeover, and the same political aspiration for democracy, why are their stances on Hong Kong migrants’ current situation discrepant and conflictual? Here, we argue that the key to such a response pattern rests upon the different “cultural schemas” of the two societies.

One should be reminded that the term “cultural schema” is borrowed from William Sewell Jr.’s tripartite definition of “structures”, which are, according to him, “composed simultaneously of cultural schemas, distributions of resources, and modes of power” [41]. Thanks to these three conceptually distinct elements that operate interlocking in special contexts, “consistent streams of social practice” are reproduced (1996:842). In simpler terms, cultural schemas, distributions of resources, and modes of power refer to the cultural, economic, and political dimensions, respectively, which are inherent in the constitution of social structures. In this conceptual trio, “cultural schemas” are by nature to “provide actors with meanings, motivations, and recipes for social action” [41]. (Sewell continues: “Resources provide them (differentially) with the means and stakes of action. Modes of power regulate action—by specifying what schemas are legitimate, by determining which persons and groups have access to which resources, and by adjudicating conflicts that arise in the course of action. We can speak of structures when sets of cultural schemas, distributions of resources, and modes of power combine in an interlocking and mutually sustaining fashion to reproduce consistent streams of social practice” [41].) Back to the context of this study, the informants’ narratives have offered important hints for us to identify the key differences in the cultural schemas of the two societies.

During the interviews, the informants expressed the Janus-faced nature of human touch in Taiwanese society. This everyday logic, which entails caring, courtesy, and kindness in interpersonal interactions, is commonly considered by Hongkongers as a cultural virtue. However, when it comes to situations where the informants attempt to stand firm on their quests for citizenship and take reference from what is exactly stipulated in laws and regulations, they usually find that the Taiwanese respond defensively and consider Hongkongers unreasonable. As a result, the Hongkonger’s cogent appeal to what is stated in “black and white”—which is motivated by the cultural schema of the rule of law—is usually deemed in Taiwan society as impolite and unkind—as opposed to the cultural schema of the “human touch”.

Most Hong Kong migrants choose to migrate to Taiwan to rebuild their accustomed way of life they fear losing in Hong Kong. However, the informants realized that the Hong Kong way of life—often articulated as having a high degree of agility, flexibility, and internationalization—was difficult to take root in the soil of Taiwan—where its cultural schemas emphasized humbleness, the status quo, and the moral–emotional judgment. Such cultural differences become unbearable to both societies when it comes to the Hongkongers’ quests for permanent residency. Those who see their applications delayed without being given an explanation find the Taiwan authorities unfaithful and defying outright the value of the rule of law. But, on the other hand, the Taiwanese authorities seem to urge Hongkongers to express more empathy for the worries of Taiwanese society in the face of Beijing’s political threat and the influx of tens of thousands of Hong Kong immigrants. The cultural predisposition of the rule of law to inform social practice in one society, and that of human touch in another, constitutes the key difference in the cultural schemas, and by association, cultural conflicts between the two societies.

Then, what is the cost of such a misunderstanding of cultural similarity? To the Hong Kong migrants who feel deeply frustrated and who contemplate onward migration, the cost is huge—both financially and psychologically. But how about Taiwan? The Taiwan government may lose support from millions of pro-democratically minded Hongkongers. Taiwanese society may lose tens of thousands of Hong Kong immigrants—for now and in the foreseeable future—who bring with them money, knowledge, and an internationalized worldview to the self-governed island. But, do these losses matter to the Taiwanese populace? Will these losses matter in a big way to the complexion of the cross-strait tensions? Our conjecture is that they do not.

6. Recommendations

To address the disappointment felt by Hong Kong migrants regarding the changing attitudes of Taiwanese authorities toward permanent residency approval, several recommendations are proposed.

First, differential treatment should be considered for previous versus future applications. For those who applied previously under more lenient policies and invested significant resources through business or property investments, more transparency and leniency are warranted. To alleviate security concerns, the government could subject approved applicants to regular checks for national security threats. Regarding future applications, while it is reasonable for Taiwan to tighten immigration policies, it is essential to explicitly communicate these national security concerns to potential applicants. Second, more direct communication is needed regarding unacceptable versus acceptable reasons for migration or length of residency. Vague accusations of using business or investment solely to obtain permanent residency breed distrust and uncertainty. Well-defined guidelines would provide clarity for compliance. Finally, greater assistance and outreach from Taiwanese authorities and local NGOs could help address the emotional frustrations of Hong Kong migrants during this transition. While security must be balanced with humanitarian concerns, unchecked negative emotions within this community could potentially affect social cohesion over time. Open dialogue and assistance in integrating successfully could benefit both migrants and the wider Taiwanese society.

7. Limitations

We acknowledge certain limitations of the study due to the relatively small sample size. However, as mentioned earlier, the sample was not intended to be statistically representative or allow a broad generalization of all Hong Kong migrants in Taiwan. Rather, our goal was to qualitatively explore and unravel emerging cultural tensions between Hong Kong and Taiwan through in-depth participant narratives and survey responses. Despite the small sample, important themes and patterns did emerge that provide a foundation for future large-scale research. In addition, the mixed-methods approach allowed us to triangulate qualitative and quantitative data to gain a deeper contextual understanding not possible through surveys alone. While the experiences captured may not be fully generalizable, the nuanced qualitative interview data help illuminate the psychological dimensions of migration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-C.H.; Methodology, W.-C.H.; Formal analysis, W.-C.H.; Investigation, W.-C.H.; Data curation, K.K.-w.F.; Writing – original draft, W.-C.H. and K.K.-w.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by Departmental Ethical Review Committee, Department of Social and Behavioural Sciences, City University of Hong Kong, Approval Code: SSBSSU2 (Li Wai Yin, 56457768), Approval Date: 25 April 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Daily News. Taiwan Wins for Sceneries and Human Touch. 25 November 2013. Available online: http://mays2.weebly.com/9679-214882877125104282072015426032312272766522320-390802622321644201542477321619215602434120154.html (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- TVBS. In Love with Leisure Southern Taiwan. 11 November 2013. Available online: https://news.tvbs.com.tw/life/510234 (accessed on 4 February 2023).

- Ho, W.-C.; Tran, E. Hong Kong-China Relations over Three Decades of Change: From Apprehension to Integration to Clashes. China: Int. J. 2019, 17, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.C.; Hung, C.M. Youth political agency in Hong Kong’s 2019 antiauthoritarian protests. HAU J. Ethnogr. Theory 2020, 10, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, G.; Lam, C.W. Hong Kong National Security Law: What Is It and Is It Worrying? BBC. 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-52765838 (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Mak, H.Y. 港版國安法:移民查詢單日急升十倍 [Hong Kong National Security Law: INQUIRIES about Immigration Surge Tenfold in A Single Day] HK01. 22 May 2020. Available online: https://www.hk01.com/社會新聞/476612/港版國安法-移民查詢單日急升十倍-年輕人將首期作資本?utm_source=01webshare&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=non_native (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- The Stand News. Fearing the National Security Law, Hongkongers Say Farewell to their Home City. 1 October 2020. Available online: https://globalvoices.org/2020/10/01/fearing-the-national-security-law-hongkongers-say-farewell-to-their-home-city/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Yuen, V. The Population Exodus that will Change Hong Kong Forever. East Asia Forum. 25 August 2021. Available online: https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2021/08/25/the-population-exodus-that-will-change-hong-kong-forever/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- People.CN. Xi Jinping: Speech at the 40th Anniversary of the Release of the Letter to Taiwan Compatriots. 2 January 2019. Available online: http://cpc.people.com.cn/BIG5/n1/2019/0102/c64094-30499664.html (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Wu, J. The Hong Kong-Taiwan Nexus in the Shadow of China. Asia-Pacifc J. Jpn. Focus 2022, 20, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, L.; Chen, A. Taiwan Offered Hope after They Fled Hong Kong. Now, They’re Leaving Again. The Washington Post. 31 May 2022. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/05/31/taiwan-hong-kong-immigration-china/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Beazley, J. China-Taiwan Tensions: How Worried Should We Be about Military Conflict The Guardian. 4 August 2022. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/aug/04/china-taiwan-tensions-how-worried-should-we-be-about-military-conflict (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Yip, H. Why Taiwan’s Welcome Mat for Hongkongers Is Wearing Thin; Hong Kong Free Press: Hong Kong, China, 2022; Available online: https://hongkongfp.com/2022/06/26/why-taiwans-welcome-mat-for-hongkongers-is-wearing-thin/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Lee, Y.; Lague, D. Chinese Spies Have Penetrated Taiwan’s Military Reuters. 20 December 2022. 2021. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/taiwan-china-espionage/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Chiu, A. The Politics of Hong Kong Migration in the UK and Taiwan. Taiwan Insight. 18 October 2021. Available online: https://taiwaninsight.org/2021/10/18/the-politics-of-hong-kong-migration-in-the-uk-and-taiwan/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Liu, C.; Fung, K.; Lin, A. 國人對港澳居民移民態度調查報告 [Survey on public attitudes towards migrants from Hong Kong and Macau]; (Unpublished report); Taiwan-Hong Kong economic and cultural cooperation Council: Taiwan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Q. Strengthened Security Reviews Significantly Weaken the Willingness of Hong Kong Residents to Migrate to Taiwan. Voice of America Chinese. 2022. Available online: https://www.voacantonese.com/a/hk-macau-residents-face-difficulty-in-becoming-taiwan-citizens-20221117/6838499.html (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Ottonelli, V.; Torresi, T. When is Migration Voluntary? Int. Migr. Rev. 2013, 47, 783–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P. Forced, Reluctant, and Voluntary Migration. Thought Co. 21 January 2020. Available online: https://www.thoughtco.com/voluntary-migration-definition-1435455#:~:text=People%20either%20are%20made%20to,choose%20to%20migrate%20(voluntary) (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Karadeniz, C.; Okvuran, A. Engagement with Migration through Museums in Turkey. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2022, 37, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.; O’reilly, K. Migration and the Search for a Better Way of Life: A Critical Exploration of Lifestyle Migration. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 57, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, E.D. Principles of Protection for Internally Displaced Persons. Int. Migr. 2000, 38, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economic Times. China Seeks India’s Support for Its New Draconian Law to Crackdown on Hong Kong Protestors. 23 May 2020. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/china-seeks-indias-support-for-its-new-draconian-law-to-crackdown-on-hong-kong-protestors/articleshow/75892948.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Delgado, K.Z. The Past and Future of Migration, Poverty, and Small-Scale Agriculture in Mexico. Senior Thesis, Claremont McKenna College, Claremont, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hackenberg, R.; Wilson, C.R. Reluctant Emigrants: The Role of Migration in Papago Indian Adaptation. Hum. Organ. 1972, 31, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.F. The Reluctant Migrants: Migration from the Italian Veneto to Central Massachusetts; Teneo Press: Amherst, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bakewell, O. Unsettling the boundaries between forced and voluntary migration. In Handbook on the Politics and Governance of Migration; Carmel, E., Lenner, K., Paul, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2021; pp. 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Erdal, M.B.; Oeppen, C. Forced to Leave? The Discursive and Analytical Significance of Describing Migration as Forced and Voluntary. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2018, 4, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piguet, E. Theories of Voluntary and Forced Migration. In Routledge Handbook of Environmental Displacement and Migration; McLeman, R., Gemenneeds, F., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New Work, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, N.M. Return Migration and Identity: A Global Phenomenon, a Hong Kong Case; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, N.G.; Basch, L.; Blanc-Szanton, C. Transnationalism: A new analytic framework for understanding migration. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1992, 645, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, B. Refugees and asylum seekers’ emotions in migration studies. RIEM. Rev. Int. De Estud. Migr. 2021, 11, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccagni, P.; Baldassar, L. Emotions on the move: Mapping the emergent field of emotion and migration. Emot. Space Soc. 2015, 16, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierenbeck, I.; Spehar, A.; Naseef, T. Newly arrived migrants meet street-level bureaucrats in Jordan, Sweden, and Turkey: Client perceptions of satisfaction–dissatisfaction and response strategies. Migr. Stud. 2023, 11, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, K. Dissatisfaction with immigration grows. People Place 2008, 16, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- De Haas, H. The migration and development pendulum: A critical view on research and policy. Int. Migr. 2012, 50, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce, D.K. US citizens’ current attitudes toward immigrants and immigration: A study from the general social survey. Soc. Sci. Q. 2018, 99, 1467–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaaty, L.; Steele, L.G. Explaining attitudes toward refugees and immigrants in Europe. Political Stud. 2022, 70, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, K.R. Anti-immigrant sentiment and opposition to democracy in Europe. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2021, 19, 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Dalton, B.; Willis, J. The onward migration of North Korean refugees to Australia: In search of cosmopolitan habitus. Cosmop. Civ. Soc. Interdiscip. J. 2017, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, W.H. Historical events as transformations of structures: Inventing revolution at the Bastille. Theory Soc. 1996, 25, 841–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).