Young People’s Construction of Identity in the Context of Southern Europe: Finding Leads for Citizenship Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

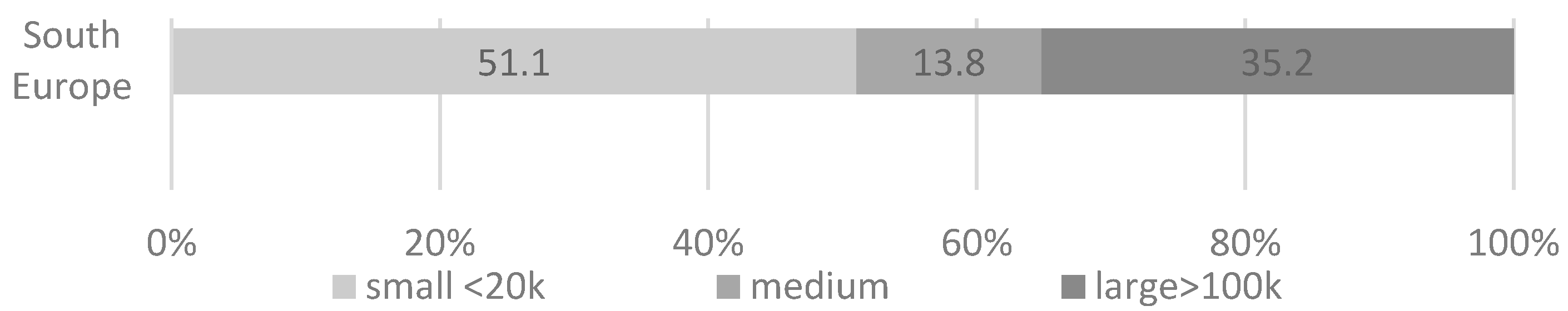

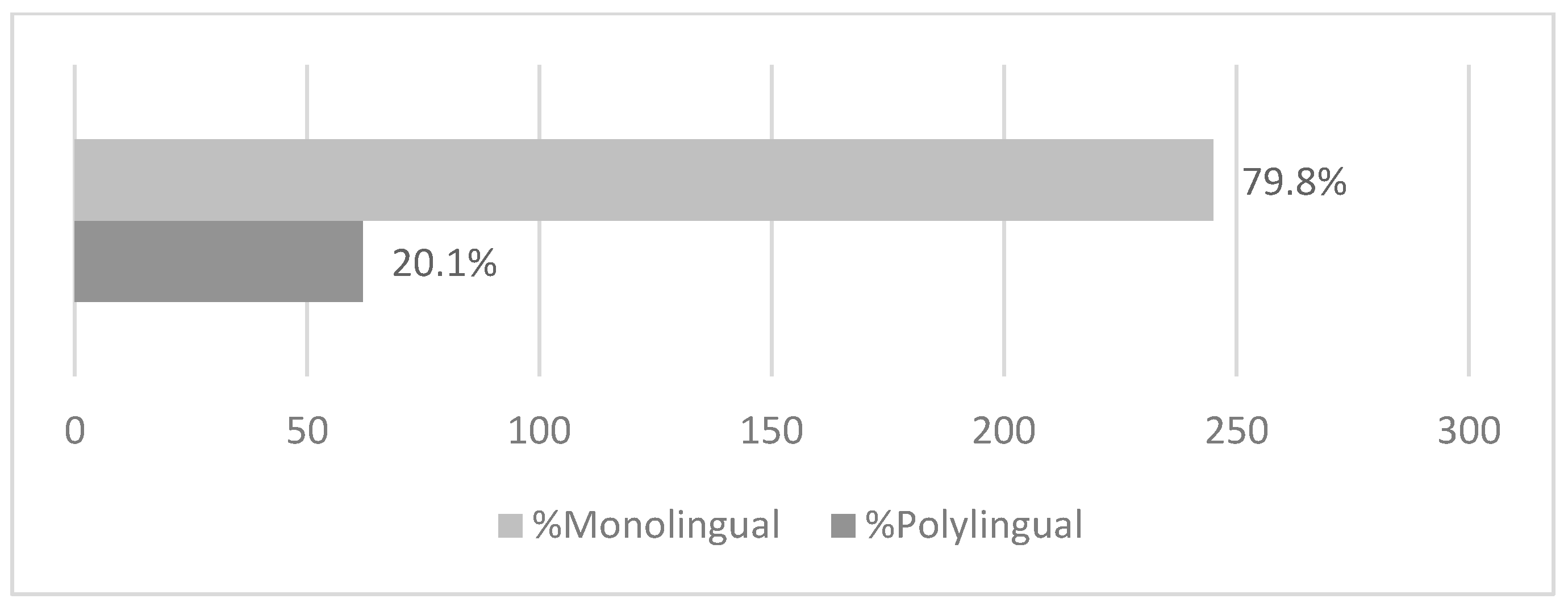

2.1. Data Collection and Participants

2.2. On Data Instruments and Analysis

3. Results

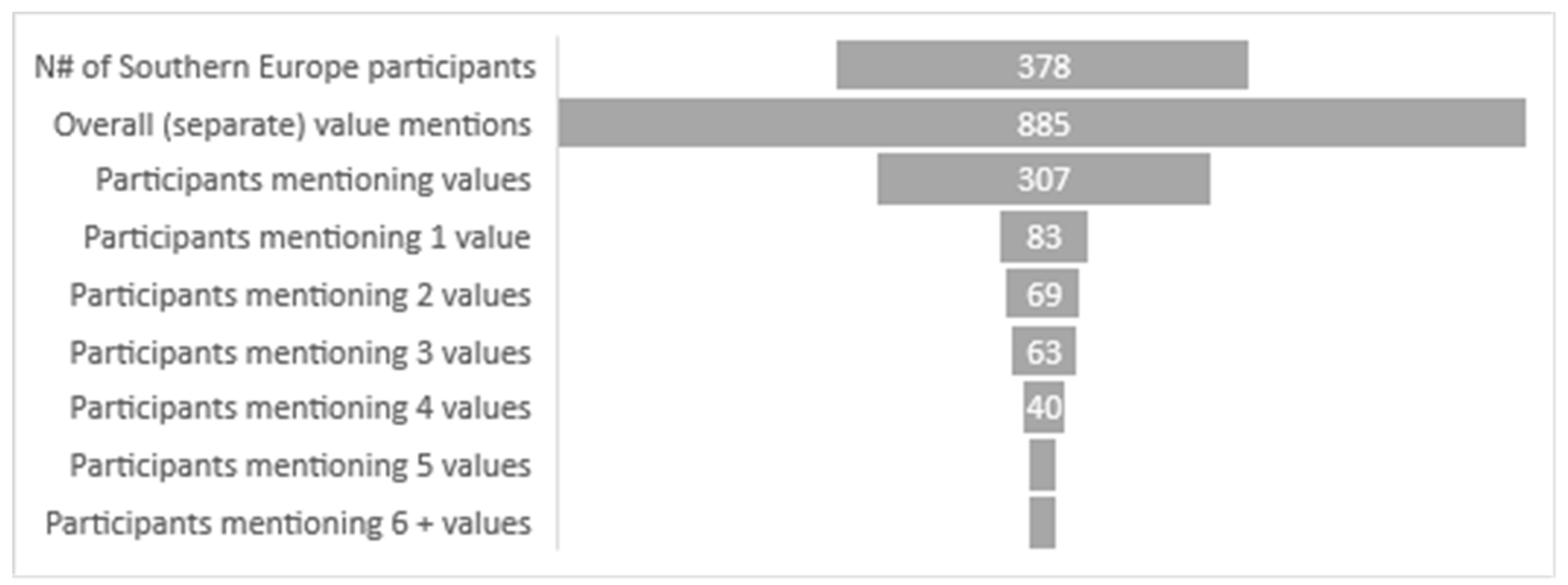

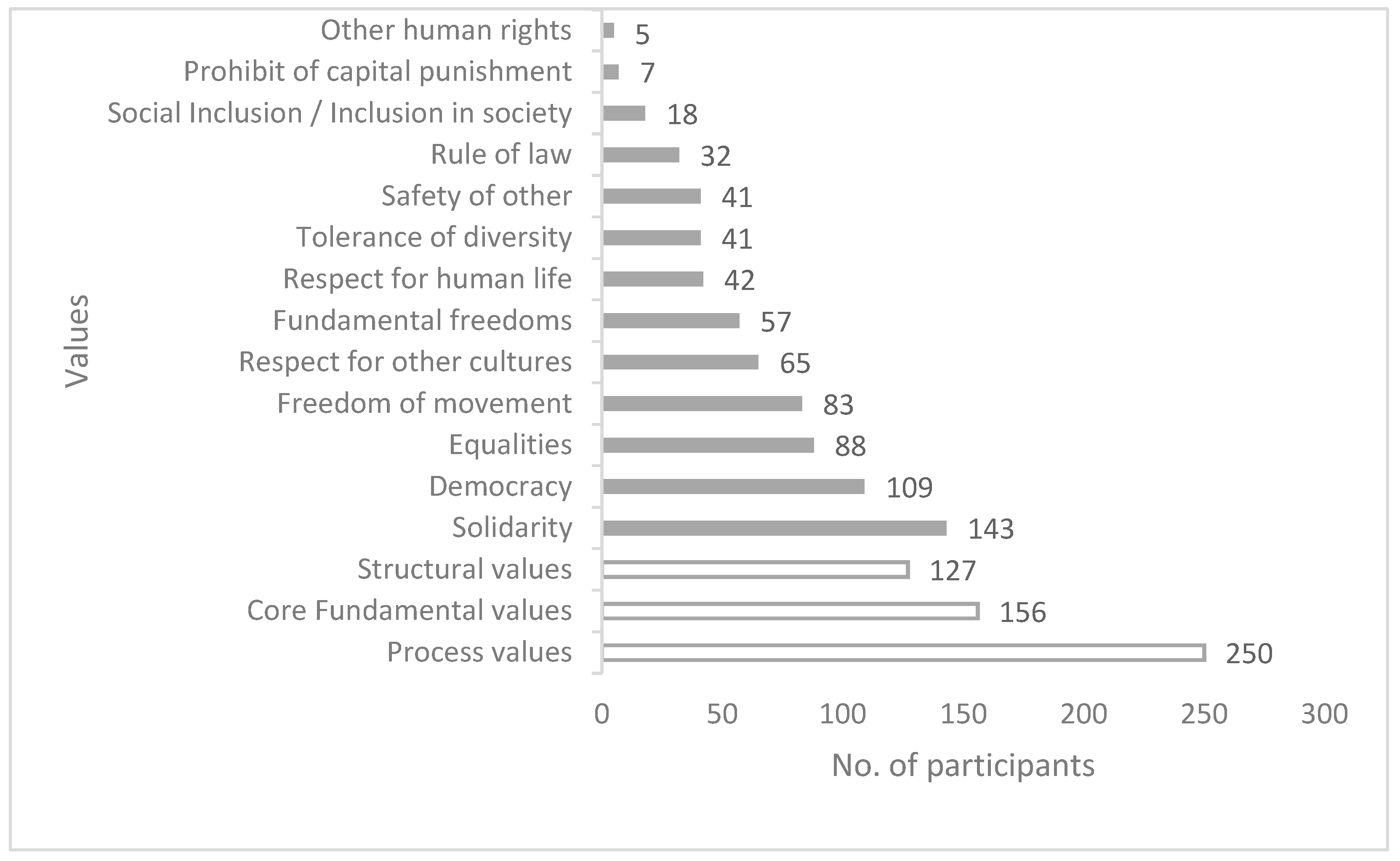

3.1. Exploring the Landscape of Mentions of Values

3.1.1. Process Values

I think it’s important to be proud of the European Union because countries together are more powerful, and can defeat problems together.(F 13, Spain)

(…) one day Italy will be a good country, and the people will live better than now—but if no one now cares about the problems, then the problems will be bigger, and we’ll have nothing.(F 16, Italy)

(…) I think Europe made a mistake—they accepted Cyprus although we are divided, and they didn’t help us re-unite the country.(F 13, Cyprus)

[I would like us to have] [m]ore money; to have more employment centers.(M 16, Portugal)

(…) being European is good because we can travel across Europe (…). I’d like to go to other countries, and try to work there—France, or England.(M 16, Portugal)

I feel more European than Spanish, but I don’t travel a lot, far from Spain—but I think if you have a high level of [education] you would have more opportunities for a job outside of Spain (…).(M 16, Spain)

I think older people in general have more closed minds—for example, the old people look at me with my tattoos and go whaw!—why, why?(F 18, Spain)

[I am pleased about] [f]reedom of speech [in Italy], because in Africa, there isn’t this.(M 13, Italy)

You say young people are not religious—but we are religious—but not so much. Because in the old times, children had to go to the church every day—and now you can do what you want—you are free, but not so free, you have to go only one time if you like (…).(M 14, Portugal)

(…) old people were very religious and stuff like this—and because teenagers now search and have different views, they always complain about us (…). Because at that time women were inferior to men, and because now we are practically the same—it’s all so strange for them to see society like this.(F 15, Cyprus)

(…) I’m a feminist, and it bothers me that a woman receives less than a man at the end of the month, just because she’s a woman. I [think] now it’s only 13% [less] in my country, but it’s not the money, it’s the idea.(F 14, Portugal)

(…) after all, we are leading a good life—considering civil rights, gay people in Italy are not discriminated against. There is democracy. I’m proud of this.(M 17, Italy)

3.1.2. Core Fundamental Values

The refugees aren’t a problem—the problem is that some countries that say that they won’t take the refugees The refugees come here during the war, and when the war finishes, they go back to Syria.(M 14, Spain)

I believe the European Union is more civilized that the rest of the world—and we are not as civilized as the other European nations, based on our everyday behavior.(F 12, Cyprus)

(…) and here, only the Gypsies have free books—and they don’t use it, they throw away the books. A friend of mine, he wants to study, he’s intelligent, but he doesn’t have the money to get books—I don’t think that’s correct—if they want to give the books, it should be to someone who needs them, not to the Gypsies who don’t use them.(M 15, Portugal)

I think maybe we think a little bit in a different way [compared to older generations], maybe because we are born into a society that is more open to the other cultures, so I think that we have had more contact with other cultures and other countries since we were very, very young. I think this is what makes the difference, we can see how other countries work. (…). We should work on our mentality—and it’s very hard for an older person to change their mentality, but it’s easier for young people.(F 16, Italy)

I don’t think Hungary should take the refugees because Germany tells them to—they should take them because (…) they are humans, and they should not take them just because someone tells them to, but because they want to. They should want to take them because of humanity.(F 16, Spain)

(…) when we speak about Europe, yes, we have to speak about a big family, that has to help the different members—and I think sometimes this doesn’t happen—for example, immigrants, the majority of immigrants arrive in Italy, and then the other countries in the European Union don’t help Italy with these immigrants. (…). Maybe if the other countries helped each other, there might be a better situation.(M 17, Italy)

(…) there are a lot of homeless people in Portugal, or who don’t have a job, and the refugees are getting a better chance to get a job than the Portuguese people. I think European countries should help people in their own country.(M 15, Portugal)

(…) I’m Syrian so I know a lot about these things [refugees]. My parents talk to me about these things. (…). Now I’m in an association of Spanish people and (…) teenagers who are helping (…) Syrian families cross Spain. For example, we wait for them at the station, give them directions on how they can get through Spain and go to Germany or wherever they want to go. We should put our hopes in teenagers—we are the ones that are working for a better life for them, more than the government, or whatever.(F 16, Spain)

Personally, I don’t like Gypsies. I get mad when I see them. I live on a farm, and I have them near me, and they are always doing stuff, stealing. They are (…) normal people, they should work too, but they just don’t take the opportunities. They have benefits from the government, but they don’t work. They have the age, the skills to work—they just don’t want to do that, they just steal and they do stuff like that.(M 17, Portugal)

There is a difference [between Turkish and Cypriots] in the way we speak, for example, we speak differently. There is a difference in the way we are treated—if a person goes to the seaside (…) they are looked at differently. And here in Cyprus there is not that restriction. There are cultural differences—distinctive cultural differences between the two, and each group has its own cultural characteristics.(F 15, Cyprus)

Here in Spain, we have a lot of racism. We help people in the streets, but sometimes we are very cruel to people from other nations. I know some people that are very cruel to people from other nations, because they have a different skin color, or some people about the Chinese because of their eyes, and I think that’s a very big fault in Spanish society (…).(M 13, Spain)

In Italy, for example, the LGBT community isn’t recognized by anyone, and I think it’s a problem. If we don’t support each other, how can we change the world?(M 16, Italy)

3.1.3. Structural Values

In Portuguese politics, we let people walk all over us for a really long time. We’ve only had one or two revolutions in all our history, and that was only in the end, after we were really mad at the people who were hurting us (…).(F 17, Portugal)

(…) I have the same political rights as the others, that’s important, because people are [treated] equally (…).(F 19, Italy)

Because in the old times there was a dictator, and he told you what you had to do, and what you had to say, and if you didn’t think that way, I’ll go to your house and kill you. Now we are more free, not exactly free, because we are controlled by the government, (…) [but] we can feel like we want, be like we want to be, not like other people want us to be.(F 17, Spain)

I think they are mixing religion and the state [in Turkey]—that should not be mixed up with the state.(F 16, Cyprus)

(…) we are different countries, but we are subject to common rules, that you have to apply to be European. (…) we are organized and we’ve got common laws.(M 15, Spain)

I don’t think we should say that “We don’t respect the rules, so Italy is not an honest country”. We can say we don’t respect the rules so we can change to be better. I’m very optimistic.(F 16, Italy)

3.2. Exploring the Landscape of Mentions of Values in Each Country

I think that older Portuguese people (…) are more judgmental than younger people. We are OK (…) if a guy wants to wear pink and green and have tattoos, we are totally OK with that—if he wants to, we accept that and we won’t judge him. I think older people judge more.(F 14, Portugal)

It makes me very (…) mad that gay couples can’t adopt babies yet, and now we are about to change that [from 2016 on], and gay people could also only donate blood this year [2015]—that also make me very angry. We need to change; we need to grow up.(F 16, Portugal)

(…) the support of the other countries, in the currency, (…) the trade with the other countries in the European Union, so, some kind of assurance and protection, in case something goes wrong.(M 18, Portugal)

(…) the Spanish people are in a crisis, and can’t pay for their houses, and sometimes live in the street, or can’t pay for the food for their children. Just because the economy is not so good. (…) we are in crisis, and there are people that haven’t got work, jobs, and can’t eat, so it’s a pity.(F 13, Spain)

A lot of people in Catalonia think that Catalonia has to be independent, so they must have a referendum to say what they think—if there are most people that think that, well, Catalonia has to be independent. Because if there are more people that want to leave, they should [a referendum was held the day before this FG took place].(M 14, Spain)

(…) a safe place is anywhere you can say your opinion or your point of view, without anyone being angry with you.(M 12, Spain)

We’re in the European Union, where we are together. We have freedom of thought.(F 13, Italy)

My idea is that if people change their minds, automatically the new politicians should change—it’s up to the voters.(M 16, Italy)

(…) when there were the terrorist attacks in France [reference to Charlie Hebdo attacks, which took place the month before the FG], we all felt European.(M 13, Italy)

When we were about to join the EU, I thought that something would change in the situation in Cyprus, but now something is happening about our political problem, but we don’t see much happening; they haven’t helped us a lot.(M 15, Cyprus)

I don’t think you can separate people because of their views and religion. We are all the same. We need to look at everyone as brothers and sisters, we need to stick together: in the work environment, in the friendship environment, and we should support one another.(F 14, Cyprus)

I’m not really sure if we get it [Turkey enters the EU], we may have more rights. (…). It could be easy for travel into other countries.(F 15, Cyprus)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Value | Aspect | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Human dignity | Respect for other cultures | Migrants |

| Respect for life | Asylum seekers | |

| Respect for the safety of others | Refugees | |

| Prohibition of capital punishment | Race/ethnicity | |

| Prohibition of harsh punishment | Socioeconomics | |

| Gender | ||

| LGBT | ||

| Roma | ||

| Other | ||

| Freedoms | Freedom of movement (work, study, leisure, and family) | |

| Freedom of expression | ||

| Freedom of speech | ||

| Freedom of protest | ||

| Freedom of thought | ||

| Freedom of dress | ||

| Freedom of religion | ||

| Freedom of the media/press | ||

| Democracy | Democracy in general | |

| Free and fair elections | ||

| The formation of political parties | ||

| Freedom to run for elective office | ||

| The separation of political activity from religious beliefs | ||

| The expectation that the elected government will act for and secure the rights of all inhabitants | ||

| The prohibition of dictatorship and dictatorial regimes | ||

| Democracy in general | ||

| Other | ||

| Equality of rights | Gender | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Sexual orientation/LGBT | ||

| Socioeconomics | ||

| Age/ageism | ||

| Religious belief | ||

| Disability | ||

| Rule of law | For laws to be made by an elected body, through a specifically defined public process | |

| For laws to be applicable to all people | ||

| For the judiciary and judges to be independent of political and governmental bodies | ||

| For the law to be accessible to all | ||

| Other | ||

| Human rights in general | Tolerance of diversity | Migrants |

| The right to inclusion in society | Asylum seekers | |

| Tolerance of diversity | Refugees | |

| The right to inclusion in society | Race/ethnicity | |

| Socioeconomics | ||

| Gender | ||

| LGBT | ||

| Roma | ||

| Other | ||

| Solidarity | Social security | |

| Pensions | ||

| Healthcare | ||

| Education | ||

| Accessibility | ||

| Cultural provision | ||

| Public transport | ||

| Community support | ||

| Workers’ rights/unions | ||

| Promotion of peace | ||

| People with a disability | ||

| Environmental protection | ||

| Food/air/water standards | ||

| Sustainable development |

| 1. | The data discussed in this paper were derived from the the Jean Monnet Network CitEdEV—Citizenship Education in the Context of European Values. They were gathered by a single researcher before the inception of the network and sustained the activities developed by Working Group 1 (WG1), of which the authors of this paper are part, which focus on the knowledge and attitudes of young people about civil society, citizenship, and European values. Addressing the data produced in the context of WG1 for the purpose of this publication was agreed among all members. |

| 2. | Within WG1 of the Jean Monnet Network CitEdEV, a small working group was assembled to pilot the analysis. Five researchers, including this paper’s main author, jointly developed an initial coding frame and tested it. After agreement on consistency, all transcripts of the 324 deliberative discussions were coded, including those targeted here. The definition of values was also targeted in the pilot for harmonization. In this sense, we acknowledge a few quotes could sign more than one value. In such cases, agreement was made to opt for the nuclear meaning of the passage. This process obviously encompasses a subjective dimension of analysis, typical of similar qualitative studies. All of the paper’s authors participated in the analysis procedures. In all, each member analyzed around 30 transcripts. |

| 3. | A full reasoning for values classification is available in the full report made by WG1, under the coordination of Tom Loughran and Alistair Ross [Young People’s Understanding of European Values: Enhancing abilities, supporting participation and voice. Report of the Jean Monnet Network Project: Citizenship Education in the Context of European Values (CitEdEV)] (to be published soon). In this document, it is also possible to reach further detail on the context of different values mention by young people and respective analysis. |

| 4. | Although some specificites can be found in the citizenship education curricula from the different southern European countries, in general, the explored themes converge into core areas like human rights, democracy, and sustainability [29]. |

References

- Boehnke, K.; Fuss, D. What part does Europe play in the identity building of young European adults? Perspect. Eur. Politics Soc. 2008, 9, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalise, G. The Narrative Construction of European Identity. Meanings of Europe ‘from below’. Eur. Soc. 2015, 17, 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A. Multiple identities and education for active citizenship. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2007, 55, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A. Controversies and generational differences: Young people’s identities in some European states. Educ. Sci. 2012, 2, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A. Finding Political Identities. In Young People in a Changing Europe; Palgrave: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Viejo, C.; Gómez-López, M.; Ortega-Ruiz, R. Construyendo la Identidad Europea: Una mirada a las actitudes juveniles y al papel de la educación. Psicol. Educ. 2019, 25, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P.; Luckman, T. A Construção Social da Realidade: Tratado de Sociologia do Conhecimento [The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge], 23rd ed.; Editora Vozes: Petrópolis, Brasil, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. A Representação do Eu na Vida Cotidiana [Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life], 7th ed.; Editora Vozes: Petrópolis, Brasil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Landberg, M.; Eckstein, K.; Mikolajczyk, C.; Mejias, S.; Macek, P.; Motti-Stefanidi, F.; Enchikova, E.; Guarino, A.; Rammer, A.; Noack, P. Being both—A European and a national citizen? Comparing young people’s identification with Europe and their home country across eight European countries. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 15, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, H. Identidade: Juventude e Crise [Identity: Youth and Crisis], 2nd ed.; Zahar Editores: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Eder, K. A theory of collective identity. Making sense of the debate on a “European Identity”. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2009, 12, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleknonis, G. The Hidden Interest in a Common European Identity. Societies 2022, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylton, P.; Kisby, B.; Goddard, P. Young People’s Citizen Identities: A Q-Methodological Analysis of English Youth Perceptions of Citizenship in Britain. Societies 2018, 8, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, L. Theorising Identity, Nationality and Citizenship: Implications for European Citizenship Identity. Sociológia 2002, 34, 502–532. [Google Scholar]

- Medrano, J.D.; Gutiérrez, P. Nested identities: National and European identity in Spain. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2001, 24, 753–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavtcheva-Petkova, V. Towards a sociology of the EU: The relationship between socio-economic status and ethnicity and young people’s European knowledge, attitudes and identities. Young 2015, 23, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Cicognani, E.; Mazzoni, D. Cross-border friendships and collective European identity: A longitudinal study. Eur. Union Politics 2019, 20, 649–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A. Young Europeans’ constructions of a Europe of human rights. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2020, 18, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde-Liebenau, J. Raising European citizens? European Identity in European Schools. J. Common Mark. Stud. 2020, 58, 1504–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde-Liebenau, J. EU identity visions and narratives of ‘us’ and ‘them’ in European Schools. Eur. Soc. 2022, 24, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corney, T.; Cooper, T.; Shier, H.; Williamson, H. Youth participation: Adultism, human rights and professional youth work. Child. Soc. 2021, 36, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippou, S. Constructing national and European identities: The case of Greek-Cypriot pupils. Educ. Stud. 2005, 31, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, J.; Leschke, J.; Ortlieb, R.; Seeleib-Kaiser, M.; Villa, P. Comparing youth transitions in Europe: Joblessness, insecurity, institutions, and inequality. In Youth Labor in Transition. Inequalities, Mobility, and Policies in Europe; O’Reilly, J., Leshcke, J., Ortlieb, R., Seeleib-Kaiser, M., Villa, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pigozne, T.; Luka, I.; Surikova, S. Promoting Youth Entrepreneurship and Employability through Non-Formal and Informal Learning: The Latvia Case. CEPS J. 2019, 9, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hällgren, C.; Björk, Å. Young people’s identities in digital worlds. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2023, 40, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fernández, Á. El centroderecha en las transiciones a la democracia en la Europa del Sur: Entre la acomodación y la (re)implantación de culturas políticas europeas (1974–1981). Hist. Y Política 2022, 48, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, H. ‘The pawns that they moved here and there’? Microacts, room for manoeuvre, and everyday agency in the 1974 Cyprus conflict. Eur. Hist. Q. 2022, 52, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Neves, T.; Menezes, I. An Organization of the Theoretical Perspectives in the Field of Civic and Political Participation: Contributions to Citizenship Education. J. Political Sci. Educ. 2017, 13, 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC/EACEA/Eurydice. Citizenship Education at School in Europe—2017. Eurydice Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Country | Portugal | Spain | Italy | Cyprus | Southern Europe Region | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | ||||||

| Participants (No. of young people) | 64 | 122 | 137 | 55 | 378 | |

| No. of deliberative discussions | 11 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 59 | |

| Age range | 14–18 | 11–20 | 12–20 | 12–20 | 11–20 | |

| Sex | Male | 36 | 53 | 69 | 14 | 172 |

| Female | 28 | 69 | 68 | 41 | 206 | |

| Meta-Value | Value |

|---|---|

| Structural values | Democracy |

| Rule of law | |

| Core fundamental values | Tolerance of diversity |

| Respect for other cultures | |

| Respect for life | |

| Safety of others | |

| Inclusion in society | |

| No capital/harsh punishment | |

| Human rights in general | |

| Process values | Freedom of movement |

| Fundamental freedoms | |

| Equalities | |

| Solidarity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Freires, T.; Thomas Dotta, L.; Pereira, F. Young People’s Construction of Identity in the Context of Southern Europe: Finding Leads for Citizenship Education. Societies 2024, 14, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010009

Freires T, Thomas Dotta L, Pereira F. Young People’s Construction of Identity in the Context of Southern Europe: Finding Leads for Citizenship Education. Societies. 2024; 14(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleFreires, Thiago, Leanete Thomas Dotta, and Fátima Pereira. 2024. "Young People’s Construction of Identity in the Context of Southern Europe: Finding Leads for Citizenship Education" Societies 14, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010009

APA StyleFreires, T., Thomas Dotta, L., & Pereira, F. (2024). Young People’s Construction of Identity in the Context of Southern Europe: Finding Leads for Citizenship Education. Societies, 14(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010009