Victims of Child Grooming: An Evaluation in University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background: What Do We Know about Grooming?

1.2. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Being a Victim of Grooming as a Function of Gender

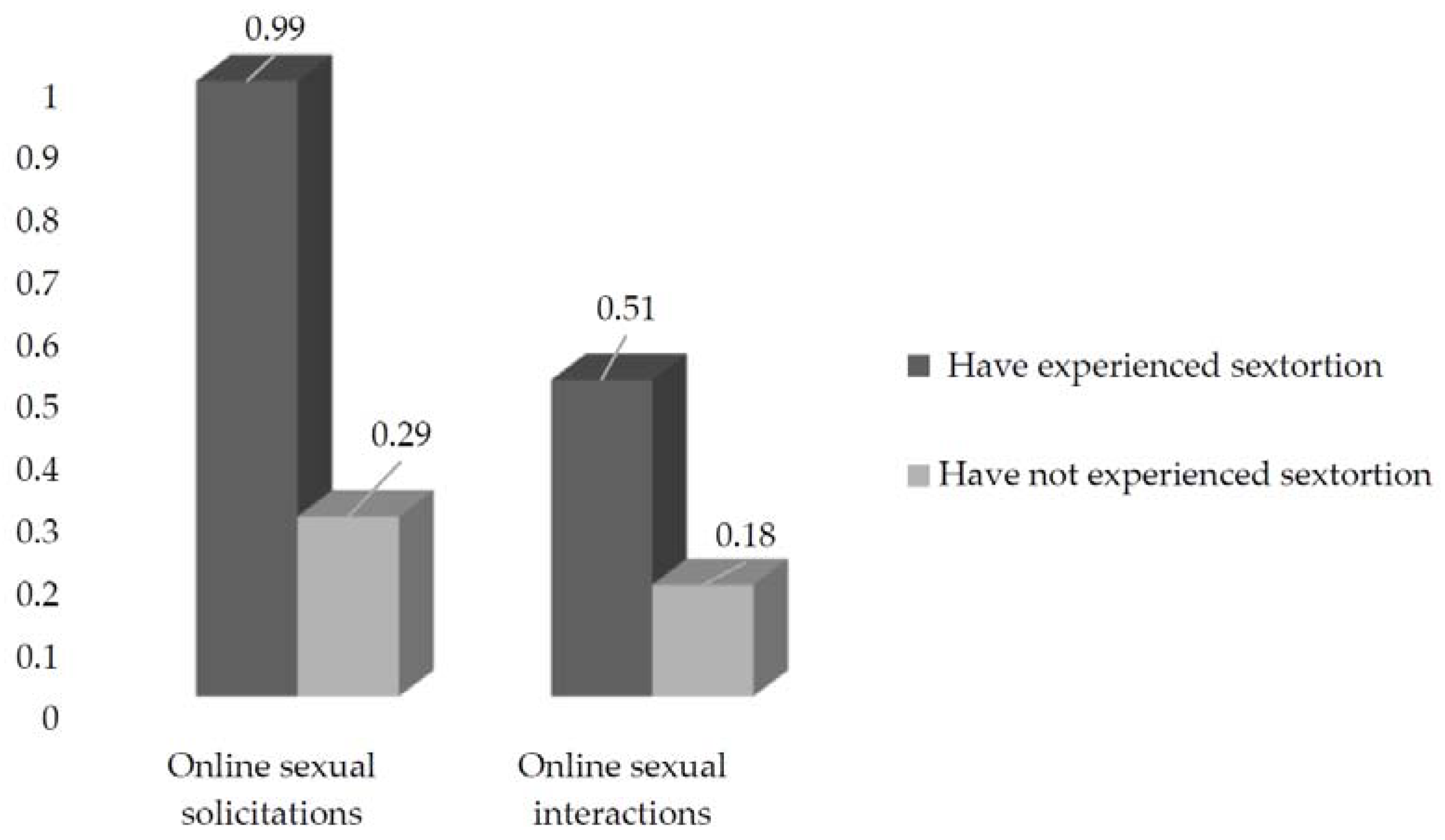

3.3. Co-Occurrence of Being a Victim of Grooming and Extortion

3.4. Analysis of the Relationship between Grooming and Consumption of Pornography

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferragut, M.; Ortiz, M.; Blanca, M.J. Prevalence of child sexual abuse in Spain: A representative sample study. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP19358–NP19377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferragut, M.; Rueda, P.; Cerezo, M.V.; Ortiz, M. What do we know about child sexual abuse? Myths and truths in Spain. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. What Works to Prevent Violence against Children Online? 2022. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/364706/9789240062061-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- United Nations. Convención sobre los Derechos del Niño. 1989. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/crc_SP.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Diario Oficial de las Comunidades Europeas. Carta de los Derechos Fundamentales de la Unión Europea. 2000. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_es.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- United Nations. Directive 2011/93 about the Fight against Child Pornography, Sexual Exploitation, and Other Forms of Sexual Abuse. 2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32011L0093 (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/objetivos-de-desarrollo-sostenible/ (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Save the Children. Ojos que No Quieren Ver: Los Abusos Sexuales a Niños y Niñas en España y los Fallos del Sistema. Available online: https://www.savethechildren.es/publicaciones/ojos-que-no-quieren-ver (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- CESW. Child Sexual Abuse in England and Wales: Year Ending March 2019. Office of National Statistics. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/childsexualabuseinenglandandwales/previousReleases (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Cantón-Cortés, D.; Cortés, M. Consecuencias del abuso sexual infantil: Una revisión de las variables intervinientes. An. Psicol. 2015, 31, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeburúa, E.; Guerricaechevarría, C.; Amor, P.J. Indicaciones terapéuticas para los menores víctimas de abuso sexual. In Abusos Sexuales en la Infancia. Abordaje Psicológico y Jurídico; Lameiras, M., Ed.; Biblioteca Nueva: Madrid, España, 2002; pp. 115–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal-Meneses, L.; Gabelas, J.A.; Marta, C. Las tecnologías de la relación, la información y la comunicación (TRIC) como entorno de integración social. Interface-Comun. Saúde Educ. 2019, 23, e180149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaureguizar, J.; Redondo, I.; Machimbarrena, J.M.; Wachs, S. Risks of “cyber-relationships” in adolescents and young people. J. Youth Adolesc. 2023, 14, 16648714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.; Gottschalk, P. Characteristics of the Internet for criminal child sexual abuse by online groomers. Crim. Justice Stud. 2011, 24, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.J.; Finkelhor, D.; Wolak, J. Risk factors for and impact of online sexual solicitation of youth. JAMA 2001, 285, 3011–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Lu, N.; Wu, D.; Jimenez, D.E.; Milanaik, R.L. Digital sextortion: Internet predators and pediatric interventions. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020, 32, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringenberg, T.R.; Seigfried, K.C.; Rayz, J.M.; Rogers, M.K. A scoping review of child grooming strategies: Pre-and post-internet. Child Abuse Negl. 2022, 123, 105392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I.; Carbonel, E.J.; Salom, M. Victimización infantil sexual online: Online grooming, ciberabuso y ciberacoso sexual. In Delitos Sexuales contra Menores: Abordaje Psicológico, Jurídico y Policial; Lameiras, M., Orts, E., Eds.; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, España, 2014; pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Quayle, E.; Newman, E. An exploratory study of public reports to investigate patterns and themes of requests for sexual images of minors online. Crime Sci. 2016, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, G.M.; Kaylor, L.E.; Jeglic, E.L. Toward a universal definition of child sexual grooming. Deviant Behav. 2021, 43, 926–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, R. A Typology of Child Cybersexploitation and Online Grooming Practices; Cyberspace Research Unit, University of Central Lancashire: Lancashire, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Winters, G.M.; Elizabeth, L.J.; Leah, L.K. Validation of the Sexual Grooming Model of Child Sexual Abusers. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2020, 29, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santisteban, P.; Del Hoyo, J.; Alcázar, M.Á.; Gámez-Guadix, M. Progression, maintenance, and feedback of online child sexual grooming: A qualitative analysis of online predators. Child Abuse Negl. 2018, 80, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broome, L.J.; Izura, C.; Davies, J. A psycho-linguistic profile of online grooming conversations: A comparative study of prison and police staff considerations. Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 109, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joleby, M.; Lunde, C.; Landström, S.; Jonsson, L.S. Offender strategies for engaging children in online sexual activity. Child Abuse Negl. 2021, 120, 105214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour-Smith, S.; Kloess, J.A. A discursive analysis of compliance, resistance and escalation to threats in sexually exploitative interactions between offenders and male children. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 60, 988–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D.; Turner, H.; Colburn, D. Prevalence of online sexual offenses against children in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2234471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.; O’Donohue, W. The construct of grooming in child sexual abuse: Conceptual and measurement issues. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2014, 23, 957–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, S.; Davidson, J.; Bifulco, A.; Gottschalk, P.; Caretti, V.; Pham, T.; Grove-Hills, J.; Turley, C.; Tompkins, C.; Ciulla, S.; et al. European Online Grooming Project—Final Report. 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257941820_European_Online_Grooming_Project_-_Final_Report (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Kopecký, K. Online blackmail of Czech children focused on so-called “sextortion” (analysis of culprit and victim behaviors). Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloess, J.A.; Hamilton, C.E.; Beech, A.R. Offense processes of online sexual grooming and abuse of children via Internet communication platforms. Sex. Abuse 2019, 31, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, G.M.; Elizabeth, L. Jeglic. Stages of Sexual Grooming: Recognizing Potentially Predatory Behaviors of Child Molesters. Deviant Behav. 2017, 38, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Guadix, M.; Martínez, J.; Almendros, C.; Martin, C.; Preedy, V.R. and Patel, V.B. The Multidimensional Online Grooming Questionnaire. In Handbook of Anger, Aggression, and Violence; Martin, C., Preedy, V.R., Patel, V.B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smahel, D.; Machackova, H.; Mascheroni, G.; Dedkova, L.; Staksrud, E.; Ólafsson, K.; Livingstone, S.; Hasebrink, U. EU Kids Online 2020: Survey Results from 19 Countries. 2020. Available online: https://orfee.hepl.ch/handle/20.500.12162/5299 (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Ali, S.; Haykal, H.A.; Youssef, E.Y.M. Child sexual abuse and the internet—A systematic review. Hum. Arenas 2021, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeglic, E.L.; Winters, G.M.; Johnson, B.N. Identification of red flag child sexual grooming behaviors. Child Abuse Negl. 2023, 136, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene-Colozzi, A.; Winters, G.; Blasko, B.; Jeglic, E. Experiences and Perceptions of Online Sexual Solicitation and Grooming of Minors: A Retrospective Report. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2020, 29, 836–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madigan, S.; Villani, V.; Azzopardi, C.; Laut, D.; Smith, T.; Temple, J.R.; Browne, D.; Dimitropoulos, G. The prevalence of unwanted online sexual exposure and solicitation among youth: A meta-analysis. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INTECO. Guía Sobre Adolescencia y Sexting: Qué es y cómo Prevenirlo. Available online: https://goo.gl/lpFJki (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Garmendia, M. Spain. In EU Kids Online: National Perspectivs; En Haddon, L., Livinstone, S., Eu Kids Online Network, Eds.; Brunner-Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; pp. 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Pereda, N.; Guilera, G.; Abad, J. Victimization and polyvictimization of Spanish children and youth: Results from a community sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2014, 38, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacampa, C.; Gómez, M.J. Nuevas tecnologías y victimización sexual de menores por online grooming. Rev. Electrónica De Cienc. Penal Criminol. 2016, 18, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Calvete, E.; Fernández, L.; Royuela, E.; Morea, A.; Larrucea, M.; Machimbarrena, J.M.; González, J.; Orue, I. Moderating factors of the association between being sexually solicited by adults and active online sexual behaviors in adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 124, 106935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Barón, J.; Machimbarrena, J.M.; Calvete, E.; Orue, I.; Pereda, N.; González-Cabrera, J. Epidemiology of online sexual solicitation and interaction of minors with adults: A longitudinal study. Child Abuse Negl. 2022, 131, 105759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Ruido, P.; Rodríguez, Y.; Lameiras, M.; Martínez, R. Sexting through the Spanish adolescent discourse. Saúde Soc. 2018, 27, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Mitchell, K.; Finkelhor, D.; Wolak, J. Internet prevention messages; Are we targeting the right online behaviors? Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gámez-Guadix, M.; De Santisteban, P.; Alcazar, M.Á. The construction and psychometric properties of the questionnaire for online sexual solicitation and interaction of minors with adults. Sex. Abuse 2017, 30, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, A.T.; Landa, B.A. Exploratory study for the development of a video game that contributes to the prevention of grooming. REPED 2021, 2, 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Barón, J.; Machimbarrena, J.M.; Caba, V.; Díaz, A.; Tejero, B.; González, J. Solicitation and sexualized interactions of minors with adults: Prevalence, overlap with other forms of cybervictimization, and relationship with quality of life. Psychosoc. Interv. 2023, 32, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón, A.L.; Navarro, E. Grooming y acoso sexual en línea: El significado y proceso de las vivencias de acoso sexual por medio de ambientes virtuales en adolescentes entre 13 y 15 años que viven en La Gran Área Metropolitana de Costa Rica. Wimblu, Rev. Estud. Psicología UCR 2023, 18, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.; Haddon, L.; Görzig, A.; Ólafsson, K. Full findings. In Risks and Safety on the Internet: The Perspective of European Children; EU Kids Online, LSE: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Y.; Alonso-Ruido, P.; González, A.; Lameiras, M.; Carrera, M.V. Spanish adolescents’ attitudes towards sexting: Validation of a scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Y.; Martínez, R.; Alonso-Ruido, P.; Adá, A.; Carrera, M.V. Intimate partner cyberstalking, sexism, pornography, and sexting in adolescents: New challenges for sex education. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 18, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D.; Turner, H.; Colburn, D. Which dynamics make online child sexual abuse and cyberstalking more emotionally impactful: Perpetrator identity and images? Child Abuse Negl. 2023, 137, 106020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rojas, A.D.; Hernando, Á.; Aguaded, J.I.; García, F.J. Sex and Affective Education at University: Evaluation of the Training of Students. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Ruido, P.; Sande, M.; Regueiro, B. ¿Pornografía al alcance de un clic? Una revisión de la literatura reciente sobre adolescentes españoles. Rev. Estud. Investig. Psicol. Educ. 2022, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiner, E.; Gómez, M.; Cardona, M. Internet and people with intellectual disability: An approach to caregivers’ concerns, prevention strategies and training needs. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2017, 6, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamar, E.; Maimon, D.; Weisburd, D.; Shabat, D. Parental guardianship and online sexual grooming of teenagers: A honeypot experiment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 137, 107386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Ruido, P.; Estévez, I.; Varela-Portela, C.; Regueiro, B. College Students’ Stereotyped Beliefs. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sanmamed, M.; Dans, I.; Muñoz, P.C.; Estévez, I. Adolescence and Digital Privacy. Rev. Mex. Inv. Ed. 2022, 27, 583–603. [Google Scholar]

- González-Sanmamed, M.; Estévez, I.; Souto-Seijo, A.; Muñoz, P.C. Ecologías digitales de aprendizaje y desarrollo profesional del docente universitario. Rev. Comun. 2020, 28, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

| Gender | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boy | Girl | Non-Binary | ||||

| Victim of grooming | Yes | Count | 321 | 73 | 7 | 401 |

| % within being a victim | 80.0% | 18.2% | 1.7% | 100.0% | ||

| % within gender | 14.3% | 7.3% | 17.5% | 12.2% | ||

| % of total | 9.8% | 2.2% | 0.2% | 12.2% | ||

| No | Count | 1924 | 930 | 33 | 2887 | |

| % within being a victim | 66.6% | 32.2% | 1.1% | 100.0% | ||

| % within gender | 85.7% | 92.7% | 82.5% | 87.8% | ||

| % of total | 58.5% | 28.3% | 1.0% | 87.8% | ||

| Total | Count | 2245 | 1003 | 40 | 3288 | |

| % within being a victim | 68.3% | 30.5% | 1.2% | 100.0% | ||

| % within gender | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % of total | 68.3% | 30.5% | 1.2% | 100.0% | ||

| Gender | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Non-Binary | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Yes | 822 | 36.9% | 861 | 87.8% | 25 | 64.1% | 1708 | 52.6% |

| No | 1408 | 63.1% | 120 | 12.2% | 14 | 35.9% | 1542 | 47.4% |

| Total | 2230 | 100.0% | 981 | 100.0% | 39 | 100.0% | 3250 | 100.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alonso-Ruido, P.; Estévez, I.; Regueiro, B.; Varela-Portela, C. Victims of Child Grooming: An Evaluation in University Students. Societies 2024, 14, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010007

Alonso-Ruido P, Estévez I, Regueiro B, Varela-Portela C. Victims of Child Grooming: An Evaluation in University Students. Societies. 2024; 14(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlonso-Ruido, Patricia, Iris Estévez, Bibiana Regueiro, and Cristina Varela-Portela. 2024. "Victims of Child Grooming: An Evaluation in University Students" Societies 14, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010007

APA StyleAlonso-Ruido, P., Estévez, I., Regueiro, B., & Varela-Portela, C. (2024). Victims of Child Grooming: An Evaluation in University Students. Societies, 14(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14010007