The Culturally Competent Healthcare Professional: The RESPECT Competencies from a Systematic Review of Delphi Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Rationale

1.3. Objective and Research Question

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection of Studies Process

2.4. Data Collection Process

2.5. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

3.1. Studies Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Study Assessment

3.4. Results of Qualitative Synthesis

3.4.1. Knowledge of Diverse Social and Cultural Contexts

3.4.2. Knowledge of Own Culture and Critical Reflection on Own Beliefs and Practices

3.4.3. Explore and Value Patients’ Perspectives

3.4.4. Showing Empathy

3.4.5. Work Together with the Patient

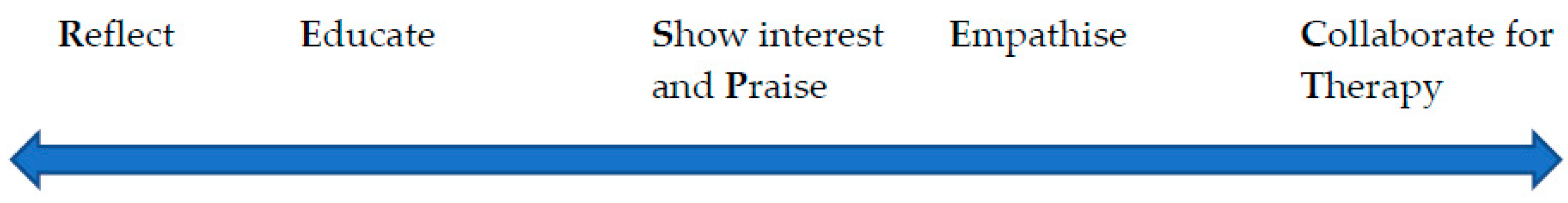

4. Discussion: Core Cultural Competencies and Guidelines

4.1. Reflect

4.2. Educate

4.3. Show Interest and Praise

4.4. Empathise

4.5. Collaborate for Therapy

4.6. Comprehensive Definition of Cultural Competence of Healthcare Professionals

“The set of abilities to continuously learn, appreciate, and reflect on the diverse social and cultural context of their own and their patients’ experiences of health and illness, value and show understanding of their patients’ behaviour, beliefs, ideas, and concerns influenced by culture and society, and work in partnership with their patients to provide culturally congruent care.”

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Curry-Stevens, A.; Reyes, M.-E. Coalition of Communities of Color. Protocol for Culturally Responsive Organizations; Center to Advance Racial Equity, Portland State University: Portland, OR, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, J.R.; Green, A.R.; Carrillo, J.E.; Ananeh-Firempong, O. Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003, 118, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, E.G.; Beach, M.C.; Gary, T.L.; Robinson, K.A.; Gozu, A.; Palacio, A.; Smarth, C.; Jenckes, M.; Feuerstein, C.; Bass, E.B.; et al. A Systematic Review of the Methodological Rigor of Studies Evaluating Cultural Competence Training of Health Professionals. Acad. Med. 2005, 80, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renzaho, A.M.N.; Romios, P.; Crock, C.; Sønderlund, A.L. The effectiveness of cultural competence programs in ethnic minority patient-centered health care—A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2013, 25, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, L.; Horey, D.; Romios, P.; Kis-Rigo, J. Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, S.; Chavan, M. Cultural competence dimensions and outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Health Soc. Care Community 2016, 24, e117–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, E.; White, V.M.; Livingston, P. Does cultural competence training for health professionals impact culturally and linguistically diverse patient outcomes? A systematic review of the literature. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 118, 105500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, D.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Park, S. Effectiveness of cultural competence educational interventions on health professionals and patient outcomes: A systematic review. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 17, e12326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skipworth, A. Systematic Review of the Association between Cultural Competence and the Quality of Care Provided by Health Personnel. 2021. Available online: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1855&context=honorsprojects (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Kleinman, A.; Benson, P. Anthropology in the Clinic: The Problem of Cultural Competency and How to Fix It. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitcomb, M.E. Preparing Doctors for a Multicultural World. Acad. Med. 2003, 78, 547–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Cultural Competence Education for Students in Medicine and Public Health: Report of an Expert Panel. 2012. Available online: https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Cultural%20Competence%20Education.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Carballeira, N. The Live & Learn Model for culturally competent family services. Contin. (Society Soc. Work Adm. Health Care) 1997, 17, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Leininger, M. Culture Care Theory: A Major Contribution to Advance Transcultural Nursing Knowledge and Practices. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2002, 13, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purnell, L. The Purnell Model for Cultural Competence. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2002, 13, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hordijk, R.; Hendrickx, K.; Lanting, K.; Macfarlane, A.; Muntinga, M.; Suurmond, J. Defining a framework for medical teachers’ competencies to teach ethnic and cultural diversity: Results of a European Delphi study. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, S.; Michaëlis, C.; Sørensen, J. Diversity Competence in Healthcare: Experts’ Views on the Most Important Skills in Caring for Migrant and Minority Patients. Societies 2022, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojanen, T.T.; Phukao, D.; Boonmongkon, P.; Rungreangkulkij, S. Defining Mental Health Practitioners’ LGBTIQ Cultural Competence in Thailand. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 2021, 29, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jünger, S.; Payne, S.A.; Brine, J.; Radbruch, L.; Brearley, S.G. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, C.S.; Andreou, P.; Nikitara, M.; Papageorgiou, A. Cultural Competence in Healthcare and Healthcare Education. Societies 2022, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.D. Visions of Culture: An Annotated Reader, 2nd ed.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Systematic Reviews: The PICO Framework. Nayang Technological University. Available online: https://libguides.ntu.edu.sg/c.php?g=936042&p=6768649 (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, L.Z.; Cipriani, A. How to carry out a literature search for a systematic review: A practical guide. BJPsych Adv. 2018, 24, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, E.; Irandoost, M.; Lorestani, H.; Sahabi, J. Identifying the Factors Affecting the Cultural Competence of Doctors and Nurses in Government Organizations in the Health and Medical Sector of Iran. J. Healthc. Manag. 2022, 12, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, D.K. Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2006, 10, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montecinos, J.B.; Grünfelder, T. What if we focus on developing commonalities? Results of an international and interdisciplinary Delphi study on transcultural competence. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2022, 89, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirwe, M.; Gerrish, K.; Keeney, S.; Emami, A. Identifying the core components of cultural competence: Findings from a Delphi study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 2622–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, D.; Kim, H.; Yoo, J.Y.; Lee, J. Agreement on Core Components of an E-Learning Cultural Competence Program for Public Health Workers in South Korea: A Delphi Study. Asian Nurs. Res. 2019, 13, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Mårtensson, L. Development of a cultural awareness scale for occupational therapy students in Latin America: A qualitative Delphi study. Occup. Ther. Int. 2016, 23, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, C.; Lindberg, D.; Morell, I.A.; Gustafsson, L.-K. Swedish experts’ understanding of active aging from a culturally sensitive perspective—A Delphi study of organizational implementation thresholds and ways of development. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 991219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farokhzadian, J.; Nematollahi, M.; Nayeri, N.D.; Faramarzpour, M. Using a model to design, implement, and evaluate a training program for improving cultural competence among undergraduate nursing students: A mixed methods study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, L.M.; Jorm, A.F.; Kanowski, L.G.; Kelly, C.M.; Langlands, R.L. Mental health first aid for Indigenous Australians: Using Delphi consensus studies to develop guidelines for culturally appropriate responses to mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry 2009, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, S.; Papma, J.M.; Berg, E.V.D.; Nielsen, T.R. Cross-cultural neuropsychological assessment in the European Union: A Delphi expert study. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2021, 36, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jervelund, S.S.; Vinther-Jensen, K.; Ryom, K.; Villadsen, S.F.; Hempler, N.F. Recommendations for ethnic equity in health: A Delphi study from Denmark. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 1–8, 14034948211040965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim-Godwin, Y.S.; Alexander, J.W.; Felton, G.; Mackey, M.C.; Kasakoff, A. Prerequisites to providing culturally competent care to Mexican migrant farmworkers: A Delphi study. J. Cult. Divers. 2006, 13, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Costa, D. Diversity and Health: Two Sides of the Same Coin. Ital. Sociol. Rev. 2023, 13, 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, C.W. The Sociological Imagination; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, J.; Kurtz, S.; Draper, J. Skills for Communicating with Patients, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T.M.; Merath, K.; Chen, Q.; Sun, S.; Palmer, E.; Idrees, J.J.; Okunrintemi, V.; Squires, M.; Beal, E.W.; Pawlik, T.M. Association of shared decision-making on patient-reported health outcomes and healthcare utilization. Am. J. Surg. 2018, 216, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion | Delphi studies published in journals or conference proceedings. Delphi studies that clearly had expert panels. Studies that explored experts’ views on the skills or competencies for cultural competence in healthcare and healthcare education, including medicine, psychiatry, nursing, and allied professions including physiotherapy, occupational health, pharmacy, social work, and psychology. Delphi studies that used the terms cultural competence, cultural humility, structural competence, cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity, intercultural communication, and diversity competence. Published from 2000–2022 in English in any country. |

| Exclusion | Studies that did not use the Delphi method. Studies conducted for fields other than medicine, nursing, and other allied healthcare. Published before 2000 and/or in a language other than English. |

| Delphi study (OR Expert Views) AND cultural competence (OR cultural humility OR structural competence OR cultural awareness OR cultural sensitivity OR intercultural communication OR diversity competence) AND health (OR healthcare OR medicine OR nursing OR psychiatry OR allied health OR physiotherapy OR pharmacy OR occupational health OR social work OR psychology OR education) |

| Citation Number | Study | Key Information | Number of Experts | Countries | Experts’ Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | Hordijk, R., Hendrickx, K., Lanting, K., MacFarlane, A., Muntinga, M., & Suurmond, J. (2019). Defining a framework for medical teachers’ competencies to teach ethnic and cultural diversity: results of a European Delphi study. Medical teacher, 41 (1), 68–74. | Aim: To formulate a framework of competencies for diversity teaching in medical education. Consensus level: 75% Delphi rounds: 3 Summary of findings: The competencies for medical teachers, on which experts reached consensus, are: self-reflection, good communication, empathy, awareness of intersectionality, awareness of ethnic backgrounds, knowledge of social determinants of health, ability to reflect with students on the social and cultural context of the patient. | 34 | Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Norway, Spain, Switzerland, the Netherlands, United Kingdom | Medical doctors, Nurses, Social scientists, Educational specialists, and Psychologists, other Public Health Scientists |

| [17] | Ziegler, S., Michaëlis, C., & Sørensen, J. (2022). Diversity competence in healthcare: experts’ views on the most important skills in caring for migrant and minority patients. Societies, 12 (2), 43. | Aim: To explore which knowledge, attitudes and skills are most important to provide good quality of care to diverse populations. Consensus level: 80% Delphi rounds: 2 Summary of findings: Authors ranked the twelve competencies that received the highest scores from experts, and these were: respectfulness, communicating understandably, identifying patient needs, addressing patient needs, self-reflection, non-discrimination, working with interpreters, finding solutions with patients, ability to listen, empathy, avoiding generalisations, open-mindedness. | 31 | Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom | Medicine and Public Health, Nursing and nursing sciences, Psychology, Social and Cultural Sciences |

| [18] | Ojanen, T. T., Phukao, D., Boonmongkon, P., & Rungreangkulkij, S. (2021). Defining Mental Health Practitioners’ LGBTIQ Cultural Competence in Thailand. Journal of Population and Social Studies [JPSS], 29, 158–176. | Aim: To investigate which competencies are important for culturally competent practice for mental health practitioners with LGBTIQ clients in Thailand. Consensus level: Interquartile ranges (IQRs) not higher than 1.5 for consensus and majority agreement Delphi rounds: 2 Summary of findings: Experts reached consensus or agreed on 100 competencies necessary for LGBTIQ cultural competence. Competencies were organised into knowledge and awareness (e.g., addressing needs, accepting gender diversity), skill (e.g., effective communication), and action competencies (e.g., showing respect). | 23 | Thailand | Mental Health Practitioners with experience in working at a LGBTIQ-focused service or have researched LGBTIQ mental health, 11 were practitioners, 12 were clients |

| [26] | Mohammadpour, E., Irandoost, M., Lorestani, H., & Sahabi, J. (2022). Identifying the Factors Affecting the Cultural Competence of Doctors and Nurses in Government Organisations in the Health and Medical Sector of Iran. Journal of healthcare management, 12 (4), 119–128. | Aim: To identify the factors affecting the cultural competence of physicians and nurses of government organisations in the health sector in Iran. Consensus level: Kendall coefficient (./704 in round 2) Delphi rounds: 2 Summary of findings: Experts reached consensus on 26 components of cultural competence, organised into cultural diversity, cultural attitude, cultural desire, cultural humility, humanistic competence, and readiness for education and organisational support. | 10 | Iran | Participants with organisational position at healthcare organisations |

| [27] | Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalisation. Journal of studies in international education, 10 (3), 241–266. | Aim: To identify and assess intercultural competence as a student outcome of internalization. Consensus level: 80% Delphi rounds: 3 Summary of findings: Experts reached consensus on 22 specific components of cultural competence. A few examples are understanding others’ views, cultural self-awareness, cultural empathy, skills to list, and flexibility. | 23 | USA | Intercultural scholars with PhDs in Communication, Political Science, Education, International Relations, Anthropology, Political Science, Psychology, and Business. Most of the participants were cross-cultural trainers and two of them were international education administrators. |

| [28] | Montecinos, J. B., & Grünfelder, T. (2022). What if we focus on developing commonalities? Results of an international and interdisciplinary Delphi study on transcultural competence. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 89, 42–55. | Aim: To rethink the competencies for transcultural competence. Consensus level: Percentage, with no specific threshold Delphi rounds: 3 Summary of findings: Competencies that related to cultural competence were: cultural awareness, open-mindedness, active listening, critical self-reflection, being non-judgmental, respect, creating a “third culture” (not yours or mine), sharing experiences, and flexibility. | 47 | Austria, Canada, Chile, China, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Slovakia, South Africa, Sudan, UK, USA, Zambia. | Experts in anthropology, cultural sciences, economics, psychology, sociology, philosophy, communications, linguistics, cross-cultural trainers and coaches. |

| [29] | Jirwe, M., Gerrish, K., Keeney, S., & Emami, A. (2009). Identifying the core components of cultural competence: findings from a Delphi study. Journal of clinical nursing, 18 (18), 2622–2634. | Aim: To identify the core components of cultural competence from a Swedish perspective. Consensus level: 75% Delphi rounds: 4 Summary of findings: These Components of cultural competencies were grouped into five general categories, namely cultural sensitivity, cultural understanding, cultural encounters, understanding of health, ill-health and healthcare, and social and cultural contexts. | 24 | Sweden | Nurses working in with a multicultural population, Researchers working on research within the field of multiculturalism, Lecturers teaching cultural issues within the nursing curriculum |

| [30] | Chae, D., Kim, H., Yoo, J. Y., & Lee, J. (2019). Agreement on core components of an e-learning cultural competence program for public health workers in South Korea: A delphi study. Asian nursing research, 13 (3), 184–191. | Aim: To seek agreement on the core components of an e-learning cultural competence program for Korean public health workers. Consensus level: 75% Delphi rounds: 2 Summary of findings: Contexts of cultural competencies were grouped into four areas: awareness (e.g., culture, ethnicity, diversity, self-awareness), knowledge (e.g., health-related cultural differences), attitude (e.g., acceptance of migrants’ health beliefs), and skills (e.g., establishing trust, effective communication skills, negotiation). | 16 | South Korea | Nursing professors, Social welfare professors, Education professors, Public administration professor, Anthropology professor |

| [31] | Castro, D., Dahlin-Ivanoff, S., & Mårtensson, L. (2016). Development of a cultural awareness scale for occupational therapy students in Latin America: a qualitative Delphi study. Occupational Therapy International, 23 (2), 196–205. | Aim: To develop a scale to assess cultural competence for Latin American occupational therapy students. Consensus level: not specified Delphi rounds: 4 Summary of findings: Experts reached consensus on items for a cultural awareness scale. The scale had 30 items that largely related to knowledge of cultural, ethnic groups, migration, gender, and social vulnerability. | 11 | Argenitna, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Venezuela | Faculty members of Occupational Therapy Programme in Latin America working in a Spanish-speaking country in the region of Latin America |

| [32] | Johansson, C., Lindberg, D., Morell, I. A., & Gustafsson, L. K. (2022). Swedish experts’ understanding of active aging from a culturally sensitive perspective–a Delphi study of organisational implementation thresholds and ways of development. Frontiers in Sociology, 7. | Aim: To explore Swedish experts’ understanding of active aging from a culturally sensitive perspective. Consensus level: 80% Delphi rounds: 3 Summary of findings: Experts reached consensus on 33 statements of cultural competence. These statements ranged from involving the elderly in decisions about their care to active listening to knowledge of other cultures and self-reflection. | 23 | Sweden | Participants in municipal decision-making positions |

| [33] | Farokhzadian, J., Nematollahi, M., Dehghan Nayeri, N., & Faramarzpour, M. (2022). Using a model to design, implement, and evaluate a training program for improving cultural competence among undergraduate nursing students: a mixed methods study. BMC nursing, 21 (1), 85. | Aim: To design, implement, and evaluate a culturally care-training program to improve cultural competence of undergraduate nursing students. Consensus level: unspecified Delphi rounds: 2 Summary of findings: Examples of the competencies that experts embraced were familiarity with culture and components of cultural diversity, importance of curiosity and empathy, and the use of negotiation and problem solving in decision making shared with patients. | 10 | Iran | Nursing faculty members |

| [34] | Hart, L. M., Jorm, A. F., Kanowski, L. G., Kelly, C. M., & Langlands, R. L. (2009). Mental health first aid for Indigenous Australians: using Delphi consensus studies to develop guidelines for culturally appropriate responses to mental health problems. BMC psychiatry, 9 (1), 1–12. | Aim: To develop guidelines for culturally appropriate responses to mental health problems among Austrian Aborigines or Torres Strait Islanders. Consensus level: 90% Delphi rounds: 3 Summary of findings: Examples of cultural competence statements experts reached consensus on were taking into account the spiritual and cultural context of the patient, learning about the behaviours that are considered signs of suicide in the person’s community, obtaining consent, and collaborating. | 28 | Australia | Participants were Aboriginal people experienced in mental health and worked in various departments such as: Private psychology clinics, Aboriginal medical services, Government health services, Universities, Cultural resource and counseling services, prisons, social services, and drug and alcohol |

| [35] | Franzen, S., Papma, J. M., van den Berg, E., & Nielsen, T. R. (2021). Cross-cultural neuropsychological assessment in the European Union: a Delphi expert study. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 36 (5), 815–830. | Aim: To examine the current state of cross-cultural neuropsychological assessment in EU-15 countries and to provide recommendations for researchers and policymakers. Consensus level: First and third quartiles (Q1–Q3) and medians Delphi rounds: 3 Summary of findings: Cultural competence knowledge and skills: knowledge of patients’ cultural and linguistic background, views, social roles, rules, religion, and traditions, working with formal and information interpreters, being flexible and patient, recognising limitations, reflecting on own culture. | 12 | Denmark, Germany, Belgium, England, Italy, Austria, the Netherlands, France, Spain | Experienced in neuropsychological assessment in patients from minority ethnic groups. |

| [36] | Smith Jervelund, S., Vinther-Jensen, K., Ryom, K., Villadsen, S. F., & Hempler, N. F. (2021). Recommendations for ethnic equity in health: A Delphi study from Denmark. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 14034948211040965. | Aim: To formulate recommendations on both structural and organisational levels to reduce ethnic health inequalities. Consensus level: Scale from 1–5, finalised recommendations and then requested final comments Delphi rounds: 3 Summary of findings: Recommendations made by experts were health policies to reflect patient needs, health promotion in co-creation with people from minority communities, interdisciplinary collaboration, cultural knowledge and awareness to ensure equal access to services, and interpreting assistance. | 9 | Denmark | Decision-makers representing municipalities, regions, the private sector and voluntary organisations. |

| [37] | Kim-Godwin, Y. S., Alexander, J. W., Felton, G., Mackey, M. C., & Kasakoff, A. (2006). Prerequisites to providing culturally competent care to Mexican migrant farmworkers: a Delphi study. Journal of cultural diversity, 13 (1). | Aim: To identify what is necessary to provide culturally competent care to Mexican migrant farmworkers. Consensus level: 80% Delphi rounds: 2 Summary of findings: Cultural competence items were organised into caring (e.g., attitudes) cultural sensitivity (e.g., self-awareness and respect of other cultures), cultural knowledge (e.g., understanding patients’ culture), and cultural skills (e.g., effective communication). | 142 | USA | Nurses |

| Citation Number | Study/CREDES Criteria | Justification | Planning and Process | Definition of Consensus | Information Input | Prevention of Bias | Interpretation and Processing of Results | External Validation | Purpose and Rationale | Expert Panel | Description of the Methods | Procedure | Definition and Attainment of Consensus | Results | Discussion of Limitations | Adequacy of Conclusions | Publication and Dissemination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | Hordijk et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| [17] | Ziegler, Michaëlis and Sørensen | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| [18] | Ojanen et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| [26] | Mohammadpour et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| [27] | Deardorff | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| [28] | Montecinos and Grunfelder | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| [29] | Jirwe et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| [30] | Chae et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| [31] | Castro et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| [32] | Johansson et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| [33] | Farokhzadian et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| [34] | Hart et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| [35] | Franzen et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| [36] | Jervelund et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| [37] | Kim-Godwin et al. | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Constantinou, C.S.; Nikitara, M. The Culturally Competent Healthcare Professional: The RESPECT Competencies from a Systematic Review of Delphi Studies. Societies 2023, 13, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13050127

Constantinou CS, Nikitara M. The Culturally Competent Healthcare Professional: The RESPECT Competencies from a Systematic Review of Delphi Studies. Societies. 2023; 13(5):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13050127

Chicago/Turabian StyleConstantinou, Costas S., and Monica Nikitara. 2023. "The Culturally Competent Healthcare Professional: The RESPECT Competencies from a Systematic Review of Delphi Studies" Societies 13, no. 5: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13050127

APA StyleConstantinou, C. S., & Nikitara, M. (2023). The Culturally Competent Healthcare Professional: The RESPECT Competencies from a Systematic Review of Delphi Studies. Societies, 13(5), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13050127