Abstract

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, digital interactions ceased to be “just another form of communication”; indeed, they became the only means of social interaction, mediated and driven by information and communication technologies (ICTs). Consequently, working in a digital context switched from being a phenomenon to be studied to the primary means of socializing and the primary workspace for researchers. This study explores four different methodologies to question how discursive interactions related to power and newsworthiness may be addressed in digital contexts. The multimodal approach was reviewed through the affordances of critical discourse analysis, issue ownership and salience, morphological discourse analysis, and protest event analysis. It starts by theoretically addressing concepts of multimodality and phenomenology by focusing on the implications of both perspectives. It examines publications and interactions in digital contexts in Ecuador from March 2017 to December 2020 within three political phenomena. The results of the analysis of these publications and interactions suggest that when analyzing political participation and newsworthiness, the virtual becomes a subjective space. Moreover, qualitative research is one of the primary ways to combine multimodality with other forms of discourse analysis. This paper concludes that perceptions, practices, and meanings assigned to social online representations can be better analyzed through multimodality, which tackles the intertwined characteristics of virtual discourses.

1. Introduction

In times of “liquid modernity”—in the Baumanian sense of the term—it is a risky undertaking to approach the analysis of interactions univocally. Moreover, digital interactions comprise a wide variety of forms of communication, including texts, images, and sounds, as well as links to other texts, images, and sounds. What makes the study of digital interactions fascinating—particularly in light of Bauman’s concept of liquid modernity—is the existence of unfamiliar people interacting directly with each other, with all its implications: “The meeting of strangers is an event without a past. More often than not, it is also an event without a future (it is expected to be, hoped to be, free of a future), a story most certainly ‘not to be continued’, a one-off chance, to be consummated in full while it lasts and, on the spot, without delay and without putting the unfinished business off to another occasion” [1] (p. 95).

In light of these findings, with regard to digital interactions, the concepts of multimodality and phenomenology prompt knowledge on this subject to continuously reset and shift when analyzing newsworthy political and social phenomena.

1.1. Key Concepts in Multimodality

Until the linguistic turn, language was studied as an isolated linguistic system, without considering the role of people in shaping language, such as the social functions that they bestow upon language in particular contexts and situations. In 1979, Halliday began considering language a social semiotic system, thus addressing the social nature of communication. It is through language that a human becomes a social being, and the language system is understood as “a system of options and meaning potentials: in summary the idea of meaning as choice” [2] (p. 252).

The social context is described as a multidimensional semiotic space in which semiotic systems—including linguistic systems—as well as social systems operate and communication takes place. This is due to the fact that the social context is a symbolic environment, and symbols operate in a multidimensional space [3]. The three variables that constitute the interdependent axes of the situational context are: a “field” of social processes (what is happening); a “tenor” of social relations (who is involved); and a “mode” of symbolic interaction (how meanings are exchanged) [4,5,6].

The field refers to the “what” of the situation, that is, the nature of the social and semiotic activity as well as the theme or issue relative to the domain of experience to which the activity is related. The tenor concerns who interacts in the situation; in other words, the roles of the interlocutors—institutional, power, closeness and contact, sociometric—as well as the value charge that the actors attribute to the domain.

Finally, there is the mode. The mode is understood as the role that language or another semiotic system plays in the analyzed social situation (constitutive or facilitating); it also deals with the division of tasks between the linguistic system and other semiotic systems. Furthermore, the mode refers to the direction of the text towards the field (i.e., the rhetorical system and the intention), which could be informative, didactic, explanatory, and so on. Moreover, it also refers to the 18orientation of the text towards the tenor: persuasive, exhortatory, controversial, and so on. Finally, the mode refers to an alternation or turn (monological or dialogic), the medium (written or oral), and the channel (phonic or graphic).

Although there are rules and characteristics defined in the semiotic system, the message itself is susceptible to several meanings derived from a selection of words. Furthermore, the message is intonated in a certain way, and it is accompanied by a particular gaze or gestures; such actions have significant potential that transcend the simple use of language. These new ways, or “modes” of interpersonal communication expand the repertoire of possibilities with which we can express ourselves. Moreover, these modes also increase the number of interpretative options available for expressive purposes, meaning that analyzing such phenomena becomes more complex. Introducing visual texts into the social semiotic system paved the way to multimodality [2].

The digital world is a different space that acts as a mediator between the event and the audience. Forms of mass media were characterized by a public communication model (broadcaster–message–public) that resembled the Aristotelian assembly communication model (speaker–speech–audience) [7]. Digital contexts blend or “hybridize” [8] these contemporary modes of symbolic production, and they are not limited to a single medium; rather, they merge with and complement different media, thus promoting the emergence of new differentiated forms that can build physical and virtual realities.

Certain contexts, without necessarily moving completely away from the physical, become digital and emerge within the so-called “non-places” [9]. Non-places lack property; they are spaces designed for public use, and they lack symbolic expressions of identity, relationships, and history. Auge [9] affirms that the moment in which we live is that of “supermodernity”, which is distinct from the postmodern—an era characterized by abundance. A superabundance of events makes it impossible to reflect on time, where everything happens simultaneously; this makes it difficult to be distant from time as it is “overloaded with events that hinder both the present and the recent past” (p. 36).

In “supermodernity”, one lives for a long time, and three or four generations can coexist simultaneously; in practice, this makes it possible to expand the collective, genealogical, and historical memory. A second feature of the excessive nature of supermodernity corresponds with space, “correlative to the shrinking of the planet” (p. 37). It is within these supermodernity digital contexts that life takes place. Non-places are not limited to a reference point located in a space and a time. Non-places allow the flux of people and goods to occur in a different way, thus prompting a different understanding of space and time.

This research builds on this understanding of non-places in order to characterize digital contexts. Non-places label a type of space and place in the virtual world where events are produced and reproduced. They can only be approached through an understanding of the multiplicity of possible ways of being.

In this space, in the virtual sphere, forms of communication are modified, thus allowing for an “oral conversation in a written medium” [10] to take place, or a “third orality” [11]; this enables discussions concerning the way in which facts are clustered and the way that nuances are suppressed in the digital sphere. Moreover, there are fuzzy boundaries when interpreting messages that “jump” from one medium to another: “when an instant message (for example from WhatsApp) is shared on a microblogging platform (such as Twitter) or vice versa, the communicative situation changes and with it its context” [12] (p. 305).

Additionally, conversations generated in the digital sphere can occur asynchronously with diffuse boundaries, which makes it difficult to determine the contexts in which they take place. In other words, in the digital sphere, platforms have been created to allow people to be permanently connected with one another and to facilitate their constant interactions; in fact, the “one-off” conversation no longer exists as it is possible to have a conversation at any time, in any place.

Multimodality occurs when media convergence occurs [13]. In other words, content flows through multiple media platforms (mode), and audiences (tenor) migrate in search of content that echoes their behavior and culture; therefore, all modes of communication and information are constantly reconfigured to adapt to the demands of technology.

Multimodality conditions the methods of data collection and processing. It is concerned with dialogues (virtual conversations) that have diffuse beginnings and endings. Such dialogues are simultaneously generated on various platforms and formats; they combine text, video, and images. Moreover, multimodality could also include interactions with artificial intelligence (AI); however, the study of artificial intelligence is beyond the scope of this research paper.

1.2. Approaches to Phenomena

First, let us focus on phenomenology, which may be understood as the rigorous means by which people examine and perceive the world scientifically before they come to properly understand it. The ways in which we investigate how people experience the world, as well as how they abstract from the world around them, are derived from the work of Husserl [14]. By creating a general understanding of mental processes, Husserl created an operative abstraction. When the mind receives input via stimuli from the world around it or experiences images or sounds, something concrete or abstract occurs. How does the mind respond to tenderness and injustice? Husserl’s study is completely theoretical rather than empirical [15].

The content—concerning what is discussed or what dialogues occur in digital and convergent media—refers to Halliday’s field [5]. In this study, the field is understood as the phenomenon; thus, a phenomenon is understood as any fact, situation, or experience that is highlighted or relevant to users due to factors that answer questions such as what, who, why, and so on. As in any dialogue, the sine qua non for it to exist is that someone talks about it and interacts with it. “Someone”, according to Halliday, refers to the tenor.

Phenomenology refers to a body of knowledge that deals with empirical observations (concerning phenomena).

Husserl believed that the social world was formed before the formation of the self and the world. He also believed that people’s subjectivities were formed before intersubjectivity. The second step requires a phenomenological reduction to be performed. This eliminates the discarding process and leaves only a trace of reality in the mind. This is not the same as the impression received, but rather an impression of reality stored in the subconscious; this is what digital behavior can generate.

A central question in phenomenology is as follows: what is the intention? To answer this question, classical phenomenology uses three methods: (1) the mere description of a past experience; (2) the interpretation of the experience in relation to its context; and (3) the analysis of the type of experience. Over time, these methods have developed via: (4) semantic analysis to determine thought conditions and types of intention; and (5) experiments to confirm or refute aspects of an experience [16]. Regarding communication processes, phenomenology is mainly interested in grounding research through inquiry. Hence, interdisciplinarity is one of the strengths of studies that are based on phenomenology.

Narrative studies report stories, whereas a phenomenological study interrogates the meanings of the experiences of individuals from a phenomenon-based perspective [16]. In this sense, phenomenology does not focus on the mere description of the event but on an interpretation of the event, noting who intervened, what was experienced, and how the event occurred [17]. Phenomena are determined using facts that change over time; hence, the relationships between them are provisional. In other words, phenomena are not subject to stable conditions given that they are events and processes; therefore, when conducting research using a phenomenological lens, the possible variables and the dimensions of the object of analysis are studied. Emphasis is given to changes in and impacts on relationships between actors.

1.3. The Phenomenon of Subjectivity in Social Life

Life is conditioned by the social manner in which relationships or interactions between subjects are structured. The subject relates to themself, but at the same time, it also conveys aspects of the outside world, which are mediated by the objective conditions of the social system to which they belong. The processes of social production and reproduction, the base and the superstructure, comprise social reality, which may be understood as social relations, institutions, and ideas in their entirety. Social reality is formed by both a historical and social being, full of sense and human potential [18].

It is in this sense that the configuration of subjectivity in the presence of the other is necessary; therefore, subjectivity is the result of interactions (an action between, at least, two people, situations, or things). Consequently, the person, situation, or thing—signified by the subject—is placed in their internal world. This allows the individual to think about oneself, act with others, and build a social bond: “the existence of the subject capable of thinking as such is linked to the existence of the other. In the experience of the existence of the neighbor, the subject can become aware of his own existence” [19] (p. 57).

1.4. Newsworthiness of Political and Social Phenomena

A phenomenon refers to an event or fact that impacts the communicative sphere and requires analysis and explanation. By focusing on messages that occur in digital contexts, phenomenology is able to guide the study of the circulation and dissemination of these messages. One approach to the social repercussions of messages is to frame them in terms of their newsworthiness. Journalists generate messages with certain elements that make them suitable for publication/broadcast on a media platform, including opportunity, proximity, prominence, impact, conflict, magnitude, and rarity [20].

From a sociological perspective, qualities that contribute to a message’s newsworthiness can be classified into frequency, surprise (novel, unpredictable, or unique events), proximity, continuity, power of the elite (nations, institutions, and people), spectacle, celebrity, bad news (conflict, crime, material, or personal damage), good news, sex, significance (political, economic, or cultural), relevance (geographical or cultural proximity), authenticity, opportunities, and competition [21]. Changes in media, regarding digitalization, embrace reconfigured approaches to news writing in terms of its value criteria. They suggest that this approach may be divided into three areas: goals, factors, and values. The goals of news writing comprise a set of general objectives that writers strive to achieve, including clarity of expression, brevity, accuracy, and color, among others. In addition, news writing involves selection factors that determine whether a story is published or not, such as commercial pressures, deadlines, and the availability of reporters. These criteria are not necessarily based on value. Finally, news values are recognized criteria that determine the newsworthiness of actors, happenings, and issues. These values include negativity and proximity, among others. By understanding these objectives, factors, and values, writers can create informative, engaging, and impactful news content.

This study classifies newsworthy phenomena into political and social categories for academic purposes because there are evident overlaps between both categories. Political phenomena concern facts related to the regime or political system. Digital citizenship has become a political issue that has changed the ways in which citizens and authorities relate to each other and the ways in which decisions are communicated (both politically and in terms of policies). These phenomena have repercussions for forms of legitimization with regard to democratic political intervention. On the other hand, social phenomena refer to dialogues that are inherent to the networked community. Digital media and social networks are catalysts that reconceptualize and reimagine social relations, political and cultural participation, and so on.

The mode of symbolic interaction (how meanings are exchanged) [6] that is transferred to digital culture creates a particular pattern with which to understand how content is produced, disseminated, and regenerated. It has been suggested that the two substantial characteristics of the Information Society are as follows: the shrinking of distances and the short duration of time spent online [22]. Currently, multi-screen and cross-platform consumption can occur on the same screen at the same time. Millennials are known for using more than one medium at a time. Obtaining information in this way can cause one of the following scenarios: a) information becomes significant as the various content sources complement each other (the so-called meshing), despite being played simultaneously; or b) if a person’s attention is divided, it can make data collection useless as one content source may prove to be more distracting than the other, thus preventing the attainment of useful and efficient information (called “stacking”).

Hence, hybrid content emerges, and contrasting sources are combined to generate a third reality; at the same time, this may also be considered detached autonomous content. Faced with the task of scrutinizing messages from audio, video, and photo mixes (using apps or platforms such as TikTok), content analysis is faced with an interesting challenge: it needs to track the original sources, identify the context (so as to understand the combination (the mashup) of layers), and understand the informative purpose behind the final product.

In addition to the manner in which messages are produced, the relationship between people and the media has also been modified. The former media receiver (or consumer) inhabits two spaces at the same time: producer and consumer. As a result, the concept of “prosumer” arises, which refers to the actual simultaneous performance of three key actions: composing, sharing/participating, and disseminating (emit, share, receive). These actions have been possible since the arrival of digital social networks (social media), which thus combined the media concerning social communication (mass media) [23].

The possibilities surrounding the creation of messages are numerous and are not limited to written texts; there are multiple ways to use technologies, their applications, and devices. Once the content is created, there is a sine qua non condition to share it, and it is due to the mechanisms of social networks that enable information to be immediately disseminated.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is guided by a broad research question: how may discursive interactions, related to power and newsworthiness be addressed in digital contexts? Multimodality allows us to explore what the literature terms “mixed methods and multimethod research” (MMMR) [24]. In other words, different methods and methodologies are used for the collection and analysis of an extensive corpus. For this study, multimodality was the transverse axis that engaged with the analysis of digital interactions using combined discourse analysis methodologies. It has been argued that different methodologies can complement each other, thus providing different interpretations of phenomena, which enables researchers to make the correct choice concerning which method is most appropriate for each situation [25].

Three political phenomena were analyzed: (1) the election of the Mayor of Quito in the first trimester of 2019; (2) the protests in Ecuador during October 2019; and (3) the suspension of the Facebook and Twitter accounts of the former presidents of Ecuador and the United States, respectively. These three political phenomena were addressed, mainly using Twitter’s microblogging platform, although other virtual spaces were also visited in order to analyze how discursive interactions related to power and newsworthiness may be addressed in digital contexts.

2.1. Sample

The first analysis took place when the Mayor of Quito was elected in 2019. The data collection process comprised three periods: from February 5 to 19; from February 20 to March 6; and from March 7 to 21. Four thousand, seven hundred and thirty-four tweets and retweets, posted by the candidates, were collected. These tweets and retweets generated 20,071 replies and 96,260 retweets from third-party accounts.

The final working corpus (n = 3255) only included direct tweets composed by the candidates and not retweets from other accounts. The collected information concerning favorites, replies, and retweets from the candidates was indicative only (Table 1) and considered as a measure of engagement and interaction for qualitative analysis. The data were then classified, processed, and compared to the campaign plans offered by each candidate. Additionally, these variables were contrasted against the official results of the election.

Table 1.

Tweets and retweets per candidate for Quito’s mayoral election in 2019.

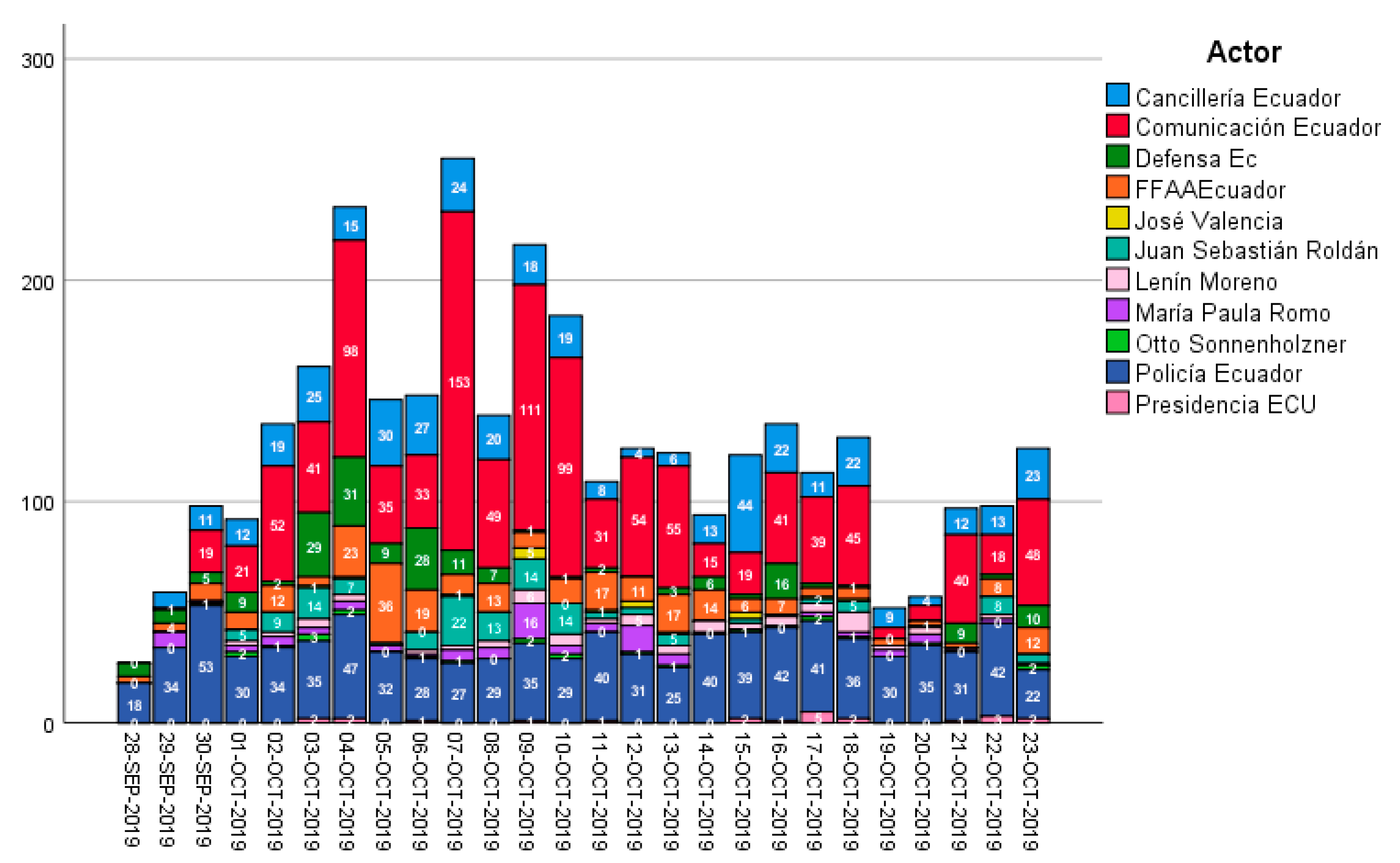

The second study also analyzed interactions on Twitter (Figure 1). A total of 4949 tweets from nine government accounts. The collection started on 28th September (to understand the general strategy) and ended on 23rd October (to allow tracing). The data were collected using the following filters:

Figure 1.

Tweets from each actor during the protests in October 2019.

- -

- filter: retweets from:Presidencia_Ec OR from:ottosonnenh OR from:Lenin OR from:mariapaularomo OR from:DefensaEC OR from:juanseroldan OR from:FFAAECUADOR OR from:PoliciaEcuador OR from:ComunicacionEc

The official information posted on Twitter by government accounts was contrasted in the analysis with posts collected from two independent local media (GK and Wambra) and mainstream media (El Comercio and El Comercio Perú).

The third study analyzed the use of memes, and the idea of a globalized sense of humor, in accordance with the media convergence model. For this analysis, memes and publications on social media, that referred to the candidates’ debates (Trump vs. Biden on 30 September 2020, and Lasso vs. Arauz on 21 March 2021), were selected in April 2021. Due to the scope of this analysis, in terms of the reappropriation of images, two memes were studied, one for each debate. The search terms were: “debate + Lasso + Arauz + meme” and “debate + Biden + Trump + meme”. It is important to underline the characteristics of reappropriation and imitation regarding social media; this allowed us to find these memes in a number of accounts and in repeated situations over time.

2.2. Methods

As previously mentioned, from both a phenomenological and symbolic interactionism perspective, multimodality in digital contexts guides this study. First, phenomenology was considered central to the issues analyzed due to their prominence in the digital sphere. Moreover, this study focused on their newsworthiness [26] and community engagement.

Participants’ use of social media platforms is shaped by the capabilities they offer, which can satisfy customers’ psychological needs and desires. These capabilities, also known as social media affordances, are multifaceted and can support a range of functions. Additionally, these affordances are interdependent, meaning that they can complement each other in a reciprocal manner [27]. Moreover, these affordances may be understood in accordance with their classical definition, wherein they are possibilities for action offered by the environment [28]; whether an affordance solicits action or not “depends on our needs and concerns” [29] (p. 686). In this sense, determining which issues were prominent in digital contexts in terms of engagement from digital audiences grounded the qualitative decisions of the selected topics that were related to the three objects of political analysis.

Then, the study focused on different approaches to critical discourse analysis; these approaches were selected depending on the scope of each particular phenomenon. As this is a methodological paper, its aim is to realize and analyze their affordances thoroughly, considering: (a) Critical Discourse Analysis; (b) Issue Ownership and Salience; (c) Morphological Discourse Analysis; and (d) Protest Event Analysis.

3. Results

Although this study is rooted in multimodality, when assessing the data for analysis, it was clear that this open and broad methodology also provides the opportunity to introduce multiple other methods to the discussion; hence, newsworthy political and social phenomena were subject to a wide variety of methodologies that were able to withstand the multimodal approach. Rather than academics posing controversial questions to assess integrated perspectives (qualitative and quantitative), concerning, for instance, “the traditional separation of qualitative and quantitative approaches that remains in most university curricula” [24] (p. 13), the multimodal approach recognizes the integrality of data; therefore, such a division has purposely not been addressed in this study.

3.1. Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) in the Memetics of Politicians

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) analyzes the power dynamics between the interlocutors of a particular discourse. Although it has been argued that power is not derived from language, this premise can be challenged [30]. CDA seeks to move language from the merely descriptive to the explanatory. In this sense, CDA focuses on the meanings that discourses hold; those hidden and implied meanings contain and account for the ideologies and beliefs of a social group [31].

The CDA approach is multidisciplinary; it draws on the complex and multifaceted interrelationships of power, ideology, and discourse [32]. Thus, the lines that separate theory and its application are thin, as the CDA methodology may be described as being overtly interpretive or hermeneutic [30].

The word “meme” defines a living structure that propagates by imitation, a neologism used to put together genes and mimesis (imitation) [33]. CDA was used to analyze a political issue on Twitter: the candidates’ debate for presidential elections in the United States and in Ecuador: Trump vs. Biden in 2020 and Lasso vs. Arauz in 2021. Both events were actively shared in digital contexts with the use of memes. Memes in social media are an interesting feature for coping with multimodality.

In this study, we refer just to two memes (one for each debate) that are representative of different forms of memes. For the United States, meme 1 compares the American debate to The Star Wars Holiday Special; for Ecuador, meme 2 pictures Dewey, the youngest brother in the series Malcolm in the Middle, which was still aired in 2020. In the tweet’s text, the author says, “if I was the moderator”, urging the moderator to provoke a fight instead of an argument.

CDA explored the background for selecting each meme and its cultural appropriations, perceiving them as direct conversations between citizens and politicians (which is how interactions on social networks should be looked at, as has been argued previously).

Meme 1 was the most difficult to analyze; therefore, it is interesting to bring it up in the discussion on multimodality. A meme does not necessarily contain images since its essence is creating a narrative rather than combining text and images. It relies on the three characteristics of the meme: copy-fidelity, fecundity, and longevity [33]. The meme is a call for action; it is trendy to screenshot a tweet (or any text) and use it as an image. Concerning scope and diffusion, authorship has much work to do. The original text from Mark Hamill, a well-known actor and writer, blames the debate on a frivolous TV show. In the case of meme 2, the Ecuadorian context needs to be explained. Politics is usually related to violence, with a long tradition of public fights at the National Assembly and other public offices that turn into fighting arenas of opposites. The broadcasted debate did not fuel citizens who were expecting, as in past events, more insults, aggressivity, disqualifications, or violent reactions.

A matrix was developed to analyze each meme in four aspects: elements (text, images or gifs, and hashtags), classification (persuasion, action, and public discussion), cultural objects, and scope [34] (Table 2). As suggested by Van Dijk, CDA seeks to explain “the use of language and discourse also in the most extensive terms of structures, processes and social, political, cultural and historical constraints” [35].

Table 2.

Memes and interactions.

Candidate debates should have been the place to develop persuasive memes, as they tend to support ideologies; instead, these memes became popular because they belong to the “public discussion” category, characterized by the use of commonplaces and cultural values. The absence of spaces for public deliberation has caused that when it comes to politics, citizens tend to criticize the marketing strategy (such as the slogans used) rather than the content itself; in that way, memes create a normative world. “New content” (memes used in conversations) tends to imitate old content instead of creating new messages; it is restricted in terms of topics and generates polarized meanings. The analysis allowed us to rethink the forms of diffusion regarding the regulations and values that emerge and are shared in liberal democratic societies.

3.2. CDA Applied to Social Demonstrations and Political Strategies

CDA was also applied to explore how government accounts developed their discourse on social protests and to examine legitimization vs. delegitimization as a construction of power. The protests had as main characters indigenous people from the countryside who traveled to Quito from all the provinces of the Andean region. They claimed that the withdrawal of gasoline subsidies had a negative impact on their communities, primarily due to the transportation of agricultural products. Then, the protests developed into an expression for the recognition of Indigenous communities in the country. Poor interaction and the absence of data led to a climate of misinformation from the very start. That is why the government decided to apply an information strategy that added a component of truthiness by using actual images of the protests in most of their posts.

The 4949 tweets from nine governmental accounts analyzed (see Section 2.1) are considered “allies” for the diffusion of official messages to study the political strategies held during this political crisis.

Building on CDA, four categories of analysis emerge: (a) redistribution vs. recognition; (b) unified political discourses; (c) legitimation vs. delegitimization; and (d) the tone of the discourse (Table 3).

Table 3.

Categories of CDA in official accounts during political demonstrations.

Redistribution vs. recognition. In the days before the arrival of the manifestants to Quito, before 1st October, the main speech from the government was about controlling speculation and their plans to benefit the poor. This can be seen as “redistribution” in terms of an attempt to balance the political and economic structures. In the beginning, the official discourse told us that Indigenous people were not demonstrating, but that political indigenous leaders were forcing them to do so. On the first days of the protest, the Ecuadorian Army posted “The Ecuadorian Army guarantees Democracy #EcuadorCountryOfPeace”, while the presidency claimed “We will not allow war, gangs, assault, and robbery to take over again. A second attempt to attack democracy, against the lives of citizens, they may not come, they may not show up”, @Lenin Moreno. #PeaceRecovers”.

Unified discourses. Most of the posts (73.15%) included text, images, or video. Initially, images were used to frame the protest and show support to President Lenin Moreno. Videos portrayed citizens’ claims against protests, a hindrance to work and development. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs framed protests as contrary to democracy; paradoxically, only a democratic system allows citizens to demonstrate. Tweets naming countries supporting the government had the tone: “Presidents from #PROSUR support the Ecuadorian government: #EcuadorCountryOfPeace #SupportDemocracy”.

Legitimation vs. delegitimization. The concepts of peace and work were used to combat social protest; one such method was to label acts committed during the protests as vandalism (delegitimization). However, when social movements agreed to take part in peace talks, the social protest was legitimized. One of the most powerful speeches was that about the economic costs of the protest, due to the curfew and the stagnation of public services. A government official tweeted: “Due to the protests, we not only stop receiving 108 million dollars, but we also lost 48 million more in repairing the damaged oil wells. Decisions have to be made so that this never happens again.” Protests were randomly legitimized, as the next tweet shows: “One thing is to demonstrate against, they have the right and possibly the duty to do so if they are in opposition, another thing is what is happening.”

Tone of speech. After the protest finished, a new tone of the speech showed up: the encouraging one. This tone is related to a better future. Then, considering that the government’s slogan is linked to planning, this is a coherent strategy. However, the permanent allusion to a better future based on promises is a characteristic of post-truth politics.

CDA suggests that government accounts provide information to Mythopoesis. This refers to the fact that legitimization is a narrative constructed by power whose outcomes reward legitimate actions and punish non-legitimate ones [36]. The government rendered the social actors involved with the protests completely invisible.

3.3. Issue Ownership and Salience in Candidate Public Speeches

Political campaigns must be understood as those that may influence voters’ perceptions of the importance of public policies and the candidate’s ability to deal with them. Each candidate will emphasize their own assets as well as the weaknesses of their opponents; this is known as issue ownership [37]. Conversely, issue salience, or the prominence of certain issues [38], is known as a result of context; it questions how important a certain issue is to voters. This is a fundamental question because an average citizen cannot be interested in all public policies; hence, macro-issues are created to encompass several important aspects of societies.

Issue ownership and salience were used to analyze the public speeches of the candidates in the Quito mayoral election (February 2019). The aim was to compare variations between speeches in terms of the initial promises or issues that were championed at the beginning of the campaign (issue ownership) and how those promises or issues likely changed in accordance with the media or political agenda (issue salience). In terms of political communication, this would reveal the consistency and coherence of the campaign.

Government plans were reviewed in order to determine the main issues in each campaign (property of the issues), which were then classified into 17 categories (Table 4).

Table 4.

Topics in the candidates’ campaign plans.

Candidates’ tweets were then classified in accordance with these same topics. Due to the large number of tweets, the next classification round only included the four candidates who received the highest number of votes; subsequently, it became possible to determine the main topics in digital discourse, of which there were six (Table 5).

Table 5.

Core topics and tweets.

The study created coefficients between work plans and cuts per candidate. At the same time, the media agenda setting was reviewed to check whether the candidate’s positions had changed (prominence of the issues).

For these two variables, a 5-value scale was used to estimate how close the narrative was to the topic in each cut, from “totally agree” on the one pole to “totally disagree” on the other. The resulting coefficient determines how much the narrative is moving away (negative) or closer and even exceeding (positive) the campaign plan. The search was flagged to understand whether tweets could show if plan points were forgotten, reinforced, or even went further as the campaign progressed (Table 6).

Table 6.

Coefficients between work plans and Twitter cuts per candidate.

It was also interesting to relate these coefficients to the results of the elections. Both candidates with the higher numbers show positive coefficients in participatory democracy; however, Yunda, who was elected Major despite the media’s agenda, remained firm in his initial speech, with positive numbers for the most. It is also interesting to see that Montúfar shows negative numbers in all six main topics; in this way, he was less active than his initial plan, with almost 30% dedicated solely to campaign speeches and propaganda. The outcomes determine that the social networks of the candidates were also used to create rivalries between the candidates instead of sharing their government plans or political motivations.

3.4. Morphological Discourse Analysis (MDA) of Candidate Tweets vs. Campaign Proposals

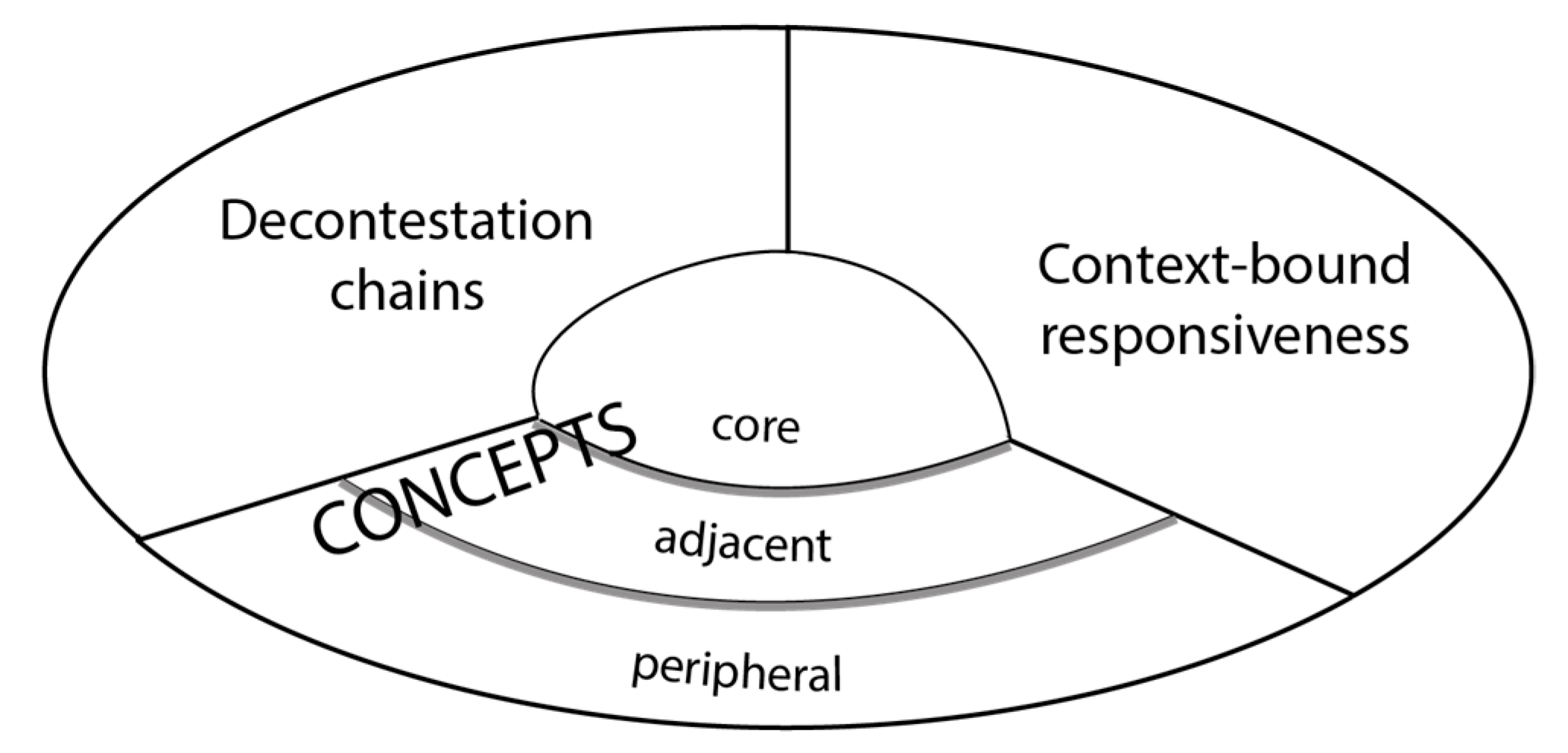

Morphological discourse analysis (MDA) is a variant of critical discourse analysis [39,40,41]. This approach has been used to understand discourse in political contexts, broadly focusing on alternatives to globalization, where ICTs play a fundamental role. Ideologies embrace specific concepts whose meanings are de-contested in political discourses. In this study, MDA was used for the analysis of the dynamics on Twitter with regard to political communication during the mayoral elections in Quito in 2019.

MDA analyzes the concepts in three stages: (1) definition of concepts; (2) “decontestation” chains; and (3) context-bound responsiveness (Figure 2). The first stage classifies the concepts of the discourses as follows: central, adjacent, and peripheral. The second identifies new linguistic forms that are provisionally created to avoid contradictions and minimize tensions caused by controversial terms; for example, regarding the terms “post-modernity” or “neoliberalism”, the prefixes “post” and “neo” modify a concept that was controversial at the time. Finally, the third stage refers to the practical alternatives that take place at a certain time and place; it seeks to reorient public issues in order to achieve positive responses and actions.

Figure 2.

MDA process.

MDA was applied to the data of the first study (n = 3255) that was first categorized following the same path as Section 3.3, resulting in 17 categories (Table 4). Twitter interactions take place in real time; that is, they are synchronous and asynchronous, but they occur within a limited timeframe [42]. For this reason, in this study, temporality worked against our methods.

A second coding cycle through MDA determined three core concepts with higher engagement and interaction: ecology (401 tweets), mobility (340 tweets), and security (264 tweets). Data were collected with the use of the Twitter archiver; months later, when the analysis took place, several tweets, responses, and interactions had already been deleted or removed from the original accounts. Additionally, the last two categories in Table 2—election campaign and others—were added only during the 3rd cut (see Section 2.1), so a number of posts were mistakenly coded: 35.9% ecology, 77% mobility, and 45% security.

The third coding cycle generated sub-themes that were adjacent and peripheral to the three core themes, and those reflected de-contestation chains and context-bound responses influenced by the subjective views of the electorate combined with a psychosocial analysis of subjectivity and social practices (Table 7).

Table 7.

Core, adjacent, and peripheral concepts about ecology, mobility, and security.

MDA is an iterative coding process that allows for the redefinition of core concepts within each category; as a result, new categories arise. Such is the case with the “urban fauna” category, where de-contestation chains were observed, especially with the use of qualifiers; previously, this term would have alluded to impoverished subjects, but now, urban fauna refers to “the voiceless”.

We noticed that one candidate tried to portray himself as an empathetic and understanding person via the links he shared. This was subsequently reaffirmed in his responses, which similarly exuded sensitivity. For instance: “RT [voter]: Do you want to know of a candidate for Mayor of #Quito 100% committed to animal #welfare and the rights of nature!?”. The tweet included a picture of the candidate walking his dogs.

Furthermore, the candidate shared private experiences, making them public: “[candidate @]: Nobody wanted to adopt the black [cat] and he ended up adopting me.” The text is accompanied by a picture of the candidate with a black cat; this was retweeted 59 times and received 348 favorites. One comment from a voter states, “For all those homeless animals. Let’s go [candidate @] to the mayor’s office. I know you will not fail them  ”.

”.

”.

”.The outcomes from digital interactions and how they build a discourse suggest that (1) the social network and the individual cannot be differentiated; and (2) every subject is contextual–epochal, and therefore, subjectivity suggests a moment in which the subject is incorporated into his own socialization process. Even though the main methodology adopted for this analysis is MDA, multimodality in tweets was present, allowing various discursive forms including texts, photos, memes, animated images, videos, emojis (such as the two dogs in the last example), and so on. Urban fauna posts were all provided by images and/or emojis; this could be one of the reasons for their high engagement rates.

3.5. Protest Event Analysis (PEA) of October 2019 Riots in Ecuador

Protest Event Analysis (PEA) is a methodology that allows the construction of “a diachronic relationship between the development of movements and social contexts” [43]. It helps to track the main events during the demonstrations. In other words, PEA provides guidelines with which to trace the chronology of events that arise from protests, using various sources of information and noting how they were framed or discussed; thus, PEA has two significant advantages. The first concerns the generation of chronologies; indeed, it facilitates the coding of events, which is essential given the volume of information involved in the analysis of a protest, where the information is abundant, simultaneous, and systematic. The second, and most important, concerns the assessment of source biases, which allows coding units to be refined and expanded.

PEA was applied to data from the October 2019 protests in Ecuador. It introduced different categories from those in Section 3.2. Using PEA, it was possible to generate a timeline of events, and such events were able to be subsequently coded. PEA analysis also involved comparisons with posts in digital media from official sources, national and international mainstream media and independent media in order to establish study categories (Table 8).

Table 8.

Main events during the October 2019 protests.

The top 10 events were generated from 1 October to 3 November. The idea was to track how government accounts addressed these 10 events in the 4949 tweets collected. The main topics of the tweets were concerned with what was happening in the streets—that is, the public demonstration itself. However, it is striking that some prominent events had little or no representation on government accounts: for instance, event #9, “cacerolazo”, a citizen’s initiative broadly spread in social media, received 0% in official media.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

From the traditional perspective of Halliday’s systemic function theory, where a social semiotic approach provides the tools to identify communicative artifacts and events and how to address them [6,44], we can identify a field; indeed, throughout this project, it has been used to mean a phenomenon. A tenor is defined as the interrelationships and threads that occur with respect to the topic, and that are addressed in digital contexts. Finally, a mode is a symbolic interaction that allows for the exchange of meanings.

The “multi” that characterizes multimodality refers in a broad sense to symbolic interactions that go beyond the text and allocution to encompass photos, videos, and the affordances of online communication, such as links, mentions, reactions, emojis, memes, and various other elements that complement, enhance, and move the communication possibilities forward. The ubiquity of the internet and online communications provides new types of communication spaces, which may be termed as non-places. The name has nothing to do with vacuity, but rather refers to the undefined “place” where such communications happen. Recalling Auge, “If a place can be defined as a place of identity, relational, and historical, a space that cannot be defined neither as an identity space nor as relational nor historical will define a non-place” [9] (p. 83). However, even non-places are impregnated with symbolism and relationships. Therefore, it is feasible to introduce a new type of place that differs from conventional places but still has its own distinctive identity.

Digital political and social newsworthy contexts have been analyzed using four different methodological approaches to discourse: critical discourse analysis (CDA), which was applied to two different events; issue ownership and salience; morphological discourse analysis (MDA); and protest event analysis. The analysis dimensions and their articulation into categories allowed for data interpretation and the assessment of the implications of the outcomes of each method.

It is important to note that recent works engaging in what has been termed “Discourse Analysis” have shifted to “Discourse Studies” so as to provide a broader outlook. The term “Discourse Studies” does not solely refer to the analysis but more broadly to how discourses are conveyed; in some ways, such discourses run “counter to the division of knowledge into specialized disciplines and sub-disciplines” [45]. In other words, a discursive turn correlates with how cultures develop multimodal places and spaces (non-spaces) that make sense of current forms of communication; these are ever-present and not situated in physical space.

This study was launched with the aim of finding “the methodology”—a unique, novel, and revolutionary methodology—for the analysis of newsworthy political and social phenomena; however, it found that there are growing numbers of scholars combining methodologies for data analysis [24]. Such scholars disagree on whether it is necessary to find multiple methodologies with which to interrogate data, in addition to whether it is necessary to adopt a broader outlook when conducting a trans-disciplinary or even post-disciplinary project. In this sense, a unique methodology, structured and fixed, was not found; rather, it was clear that the affordances of each methodology depend on the phenomena and, moreover, on the actual concerns that such phenomena involve. In political communication, the emergence of new phenomena is accompanied by the surpassing of expectations by multimodality. This approach has proven highly effective in narrowing the scope of digital interactions and analyzing them in a clear and concise manner.

Regarding the main objective of this research, “to question how discursive interactions, related to power and newsworthiness, may be addressed in digital contexts”, the numerous fields, tenors, and modes prevent a unique choice from being made. Multi-issues, multi-actions, and multi-modes cause multi-way communications, which are boosted by online ICTs. It is important to stress the fact that online communication is no longer just “a crucial medium of largely text-based communication” [46] (p. 224); indeed, it involves many other modes wherein meaning is shared, as the study of the use of memes to convey political positions shows. This is also clear when analyzing the core concepts of MDA: images, animated gifs, or emojis could accompany a written text, or they could convey meaning by themselves.

This study focuses on discourse studies of political phenomena, as it is a wider mode that encompasses how society communicates. Within discourse studies, the mixed and multi-methods approach [24,25] seems the most relevant to approach such phenomena and delve into the resulting subjective space.

The research provides valuable insights into the complex interplay between virtual communication and political engagement; however, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations that may affect the study’s contributions.

First, the paper primarily focuses on virtual political participation and newsworthiness, which may not fully capture the experiences of individuals who engage in political activities in the physical world. While virtual spaces have expanded the possibilities for political communication, they represent only one part of the broader political landscape. Secondly, the sample used in the study was drawn from a specific geographic location, which may limit the generalizability of the study’s findings to other contexts. The participants in this study were in a specific country, with particular social and cultural factors influencing their political communication. A further comparison may help with this constraint. Furthermore, the study’s multimodal analysis approach may have limitations. While this approach can provide rich insights into the complex nature of political communication, it may overlook certain aspects of communication; for example, non-verbal cues, such as body language or tone of voice, are important elements of communication. Finally, there may be other important elements of political communication that this study did not address, such as the influence of media ownership or the impact of online filter bubbles on political engagement.

In order to comprehensively understand the landscape of digital interactions, it is imperative that future research includes an investigation of the interactions performed by artificial intelligence systems. By doing so, it may be possible to simplify the complexity inherent in digital interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C., J.C.-S., M.L.-P. and A.G.-Q.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.-A.; writing—review and editing, V.Y.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project received funding from the Research Department of Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador under project number PEP QINV0353-IINV522010100.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jewitt, C. Multimodal Methods for Researching Digital Technologies. In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Technology Research; Price, S., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2013; pp. 250–265. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, S. Symbols in a Multidimensional Space. Semiotics 1990, 1990, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.; Matthiessen, C. Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.; McIntosh, A.; Strevens, P. The Linguistic Sciences and Language Teaching; Longman: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M. El Lenguaje como Semiótica Social; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Bogotá, Colombia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sosa Osorio, J.A.; Calderón, C.A. Manual de Teoría de la Comunicación / I- Primeras Explicaciones, 1st ed.; Editorial Universidad del Norte: Barranquilla, Colombia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- García Canclini, N. Culturas Híbridas. Estrategias para Entrar y Salir de la Modernidad; Grijalbo: México, Brazil, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Augé, M. Los "No Lugares", Espacios del Anonimato: Una Antropología de la Sobremodernidad; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yus, F. Ciberpragmática; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lucía, J.M. Elogio del Texto Digital; Fórcola Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara-Plá, M. El contexto de los mensajes en la comunicación digital. In El Español en la Red; Giammatteo, M., Gubitosi, P., Parini, A., Eds.; Vervuert Verlagsgesellschaft: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Convergence Culture. La Cultura de la Convergencia de los Medias de Comunicación; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. La Idea de Fenomenología; Herder: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gros, A.E. Alfred Schutz, un fenomenólogo inusual: Una reconstrucción sistemática de la recepción schutziana de Husserl. Discus. Filosóficas 2016, 17, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, C. Phenomenological Research Methods; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kosik, K. Dialéctica de lo Concreto; Grijalbo: Barcelona, Spain, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- De Gaulejac, V. Lo irreductible social y lo irreductible psíquico. Perf. Latinoam. Rev. Fac. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Sede México 2002, 10, 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, P.J. News and newsworthiness: A commentary. Communications 2006, 31, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nies, T.; D’ heer, E.; Coppens, S.; Van Deursen, D.; Mannens, E.; Paulussen, S.; Van de Walle, R. Bringing Newsworthiness into the 21st Century. In Proceedings of the Web of Linked Entities Workshop in Conjuction with the 11th International Semantic Web Conference (ISWC 2012), Boston, MA, USA, 11–15 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, R. The Information Society: Cyber Dreams and Digital Nightmares; Wiley: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- García-Galera, M.C.; Angharad, V. Prosumidores mediáticos. Cultura participativa de las audiencias y responsabilidad de los medios. Comunicar 2014, 43, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knappertsbusch, F.; Schreier, M.; Burzan, N.; Fielding, N. Innovative Applications and Future Directions in Mixed Methods and Multimethod Social Research. Forum Qual. Soz. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2023, 24, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mingers, J.; Brocklesby, J. Multimethodology: Towards a framework for mixing methodologies. Omega 1997, 25, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caple, H.; Bednarek, M. Rethinking news values: What a discursive approach can tell us about the construction of news discourse and news photography. Journalism 2016, 17, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Benitez, J.; Llorens, J.; Luo, X. Social media-driven customer engagement and movie performance: Theory and empirical evidence. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 145, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohn, N.B. Affordances revisited: Articulating a Merleau-Pontian view. Int. J. Comput. Support. Collab. Learn. 2009, 4, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dings, R. Understanding phenomenological differences in how affordances solicit action: An exploration. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2018, 17, 681–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodak, R.; Meyer, M. Métodos de Análisis Crítico del Discurso; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Raiter, A. Analizar el Uso Lingüístico Es Analizar Ideología. In La caja de Pandora: La Representación del Mundo en los Medios; Raiter, A., Zullo, J., Eds.; La Crujía: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008; pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mullet, D.R. A general critical discourse analysis framework for educational research. J. Adv. Acad. 2018, 29, 116–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkings, R. The Selfish Gene, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Shifman, L. Memes in a Digital Culture; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, T.A. El análisis crítico del discurso. Anthropos 1999, 186, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, T. Legitimation in discourse and communication. Discourse Commun. 2007, 1, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrocik, J.R. Issue Ownership in Presidential Elections, with a 1980 Case Study. Am. J. Political Sci. 1996, 40, 825–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, I. Electoral volatility: Issue effects and basic change in 23 post-war democracies. Elect. Stud. 1982, 1, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeden, M. The Morphological Analysis of Ideology. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies; Freeden, M., Sargent, L.T., Stears, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 115–137. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M.B.; Goodman, J.; Wilson, E.K. Justice Globalism: Ideology, Crises, Policy; Sage: London, UK; Los Angeles, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, D.K. The human development and capabilities approach as a twenty-first century ideology of globalization. Globalizations 2021, 18, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Albacete, G.; Theocharis, Y. Opportunities and Challenges of Analysing Twitter Content: A Comparison of the Occupation Movements in Spain, Greece and the United States. In Analysing Social Media Data and Web Networks; Cantijoch, M., Gibson, R., Ward, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA; Basingstoke, UK, 2014; pp. 119–153. [Google Scholar]

- Fillieule, O.; Jiménez, M. The Methodology of Protest Event Analysis and the Media Politics of Reporting Environmental Protest Events. In Environmental Protest in Western Europe; Rootes, C., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 258–279. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulrahman Almurashi, W. An Introduction to Halliday’s Systemic Functional Linguistics. J. Study Engl. Linguist. 2016, 4, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angermuller, J.; Wodak, R.; Maingueneau, D. The discourse studies reader. In The Discourse Studies Reader; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1–426. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Doing Qualitative Research; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).