Abstract

The use of digital technologies is one of the fundamental resources to favour the inclusion of students with special educational needs. However, recent studies continue to show a lack of use by teachers during the development of their teaching practices, especially in the field of special education. This article aims to analyse the level of digital competence of special education teachers through the perceptions of the school management team in Andalusia (Spain). The information is obtained through interviews with 62 members of school management teams. The results suggest that the low level of training and digital competence of special education teachers is the reason why they do not make use of digital tools in their teaching practice, due to a lack of teacher awareness, as well as the non-existent or insufficient development of training activities that hinder such training. In conclusion, there is a need to improve the professional development of special education teachers in digital competencies, as well as greater institutional involvement through strategic plans that promote such training.

1. Introduction

The teaching profession is in a constant state of flux, where teachers require new competencies to perform their work in a dynamic and complex context. We all know that the qualities of teachers are key to achieving educational goals. At present, international organisations and education systems around the world are designing so-called competence frameworks in response to the new competencies required by teachers in the so-called knowledge and information society.

In this context, digital competence is a requirement of the professional profile of teachers, especially if we consider that the application of technologies requires constant training of teachers. Furthermore, digital competence is key in the design, implementation and evaluation of actions aimed at understanding and improving the education of a generation of students who are digital natives [1]. Likewise, the improvement of digital competencies is identified as a guarantee for the success of teaching quality.

To promote the development of digital competence and educational innovation, at European level, the European Commission has created the European Framework for Digitally Competent Educational Organisations (DigCompOrg) and the European Framework for Digital Competences of Teachers commonly known as DigCompEdu [2]. In the Andalusian context, teacher training is a fundamental element in responding to the new educational challenges posed by society, being the key factor for the development of quality and equity in education. In this sense, the importance of the regulations governing initial and in-service teacher training in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia is clear [3]. Likewise, the Andalusian System of Ongoing Teacher Training highlights that, among the priority lines, training actions and strategies that promote the level of digital competence of teachers in accordance with the European Framework for Digitally Competent Educational Organisations (DigCompOrg), through advice and support to educational centres, should be carried out [4].

On the other hand, the literature shows that the digital proficiency of university teachers fluctuates between “low” [5], “acceptable” [6] or “medium/medium-high” [7]. This contrasts with most of the teachers’ recognition of the potential of information and communication technologies (hereinafter referred to as ICT) and their positive effect on teaching [8]. Studies such as those by García-Ruiz et al. [9] show that the level of digital competence perceived by teachers is lower than that which they possess. On the other hand, in a review of the literature on digital competence, Fernández-Batanero et al. [10] note teachers’ use of ICT for basic activities such as the presentation of visual resources or word processing programmes, followed by Internet access and, to a lesser extent, other more advanced applications such as the creation and editing of digital resources.

However, when it comes to the development of digital competence to support learners with special educational needs (SEN), the literature is more limited. Internationally, many studies highlight the importance of integrating technology to improve the learning of “all” students [11,12], but there are fewer studies that place special emphasis on students with special educational needs due to disabilities [13], even though the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [14] considers ICT as a key tool to promote equity and equal opportunities. The lack of training and knowledge that teachers have regarding the types of technologies that can be used with this group, the possibilities they offer and the function for which they can be used [15,16,17] is also highlighted. This aspect hurts the use of ICTs, hindering access to information and the empowerment of people’s capabilities and, in the case of people with disabilities, helping to alleviate their difficulties or minimising them [18].

In recent years, the study of digital competence and disability reveals that the research topics studied contain three main trends: the interaction of technology with people with disabilities; the relationship of technology with communication in people with disabilities; and the observation of the relationship between e-inclusion and digital competence [19]. In this sense, due to the importance of the integration of technologies to favour the learning of all students in the framework of an inclusive school, and the preceding problematizing context of the scarce use of technologies in special education classrooms, it is necessary to identify how special education teachers are developing their digital teaching competence. The aim of the study is to transform the development of the digital competence of special education teachers, as well as the teachers’ perception of the use of technologies in special education classrooms.

2. Purpose and Research Questions

Starting from the previous context, the aim of the research carried out was to analyse the level of digital competence of special education teachers in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia, considering the perceptions of the members of the management team of the educational centres.

Based on this objective, the following research questions (RQ) are explored:

- RQ1. What are the perspectives of the school management team on the level of digital competence of special education teachers in Andalusia?

- RQ2. Does the ownership of the school condition the level of digital competence of special education teachers as perceived by the school management team?

- RQ3. What are the perspectives of school management teams on the challenges of promoting the digital competence of special education teachers (i.e., what actions and strategies are associated with the promotion and development of digital literacy experiences)?

By answering these research questions, we aim to provide a deeper analysis of the digital competence of special education teachers, as well as to provide empirical evidence on digital teacher training experiences for special education teachers.

3. Method

3.1. Design

To respond to the research objective, a descriptive and comprehensive qualitative methodology was adopted to understand the research problem. Specifically, data were collected through semi-structured interviews.

The qualitative content analysis presented is based on Glaser and Strauss’ Grounded Theory of group and individual opinions [20]. This methodology, used in multiple research projects in the educational context [21,22], follows a coding process according to Charmaz [23] based on a systematic collection and analysis of the data to build a grounded theory on the digital competence of special education teachers.

3.2. Participants

The pool of informants consisted of 62 professionals in the education sector. Their gender distribution was 35 (60%) men and 27 (40%) women. Non-random purposive sampling was used to select the sample [24]. Table 1 provides information on the university teachers interviewed.

Table 1.

Distribution of participants by province and ownership of the school.

As can be seen, it is the school heads from Seville (f = 16, 25.81%) who participated most in the interviews, followed by those from Granada (f = 14, 22.58%) and Malaga (f = 8, 12.9%).

3.3. Instrument

The instrument used for data collection was the structured interview. These were conducted during the months of June–September 2022. The designed interview is semi-structured, combining open, closed, and multiple-choice questions, since, as Grande and Abascal [25] state, we cannot provide the answers of the participants in all the questions. The interview design aims to respond to the purpose of the study, which is to find out the level of digital competence of special education teachers.

After reviewing the specialised scientific literature on the field of study, an interview script was designed and validated through the expert judgement strategy, applying the Delphi method.

Two mechanisms were established for the selection of the experts. Firstly, they had to meet two or more of the following criteria: (a) Teaching related to “special education”, (b) Teaching related to “educational technology”, (c) Having experience in digital teacher training in the framework of an inclusive school, and (d) Having made a scientific publication related to “technology”, “special education” and “teacher training”. Secondly, the “Expert Competence Coefficient” (K-Coefficient) procedure was used for their selection, obtained from the formula: K = 1/2 (Experience Coefficient “Kc” + Argumentation Coefficient “Ka”) [26]. The value of the Coefficient K was higher than 0.8 in the 16 selected, which indicates an excellent degree of acceptance [27].

The experts’ evaluations were carried out anonymously and in successive rounds, to reach a consensus, but with the greatest possible autonomy of the participants (Delphi method). To facilitate the experts’ analysis, a four-point Likert scale has been applied to each question, where 1 is “strongly disagree” and 4 is “strongly agree” regarding the content, importance, and appropriateness of each question. There was also a section for comments at the end of the interview in case the expert wished to make any remarks. Finally, the semi-structured interview script (Table 2), consisting of 13 questions, was as follows:

Table 2.

Interview script.

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis Procedure

An exploratory study was carried out between September and December 2022. To select the sample, the official website of the “Junta de Andalucía” was consulted in order to obtain the database of all the schools in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia.

With this database, contact was attempted by telephone calls with 135 eligible schools, of which only 96 responded to the call, and finally 62 participants completed the telephone interview. Using an interview script designed by the researchers, the call explained the purpose of the study and the voluntary nature of participation in the study, informing participants that they and their school would not be identified in any future communication.

All interviews were conducted with the verbal informed consent of the participants and were audio-recorded for transcription to ensure anonymity and confidentiality, for subsequent qualitative analysis using the computer tool Atlas.Ti version 9.1 [28]. This allowed us to extract representative textual quotes from the participants.

For the analysis of the data, the technique of content analysis was used from a qualitative perspective [29]. The phases followed by the researchers were pre-analysis (by reading the interview transcripts to identify and code common themes); formation of the categorical system; coding; analysis and identification of quotes or fragments linked to the categories (evidence); and interpretation of the data using the computer tool that facilitates qualitative data analysis, Atlas.Ti.

The research process must be governed by criteria of rigour and precision that ensure the reliability and validity of the results. The credibility of the results is based on prior work on the concordance between coders (category system). To this end, we calculated the Fleiss Kappa to determine the value of the concordance between coders (reliability). We obtained a Fleiss Kappa of 0.857 for overall concordance strength. This index, according to the interpretation of Fleiss [30], can be interpreted as excellent, as it is above 0.75. Being at the highest level of agreement, we can conclude that the results are reliable and significant.

The categories selected for the study (Table 3) revolved around: professional profile (sex, province, position, length of service; ownership of the school); concept of special educational needs; digital awareness and training of special education teachers; barriers to digital training; development of training experiences and initiatives with the use of ICT; promotion of training and initiatives with the use of ICT; and priority in training.

Table 3.

Categories, subcategories, codes, and indicators resulting from the interpretative analysis of the interviews.

4. Results

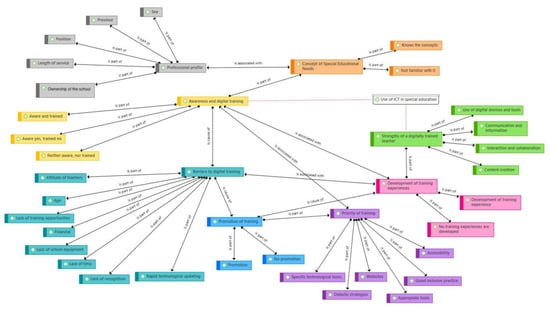

Based on the empirical basis of the informants’ perceptions, the semantic network of the categories and subcategories is presented below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Semantic network of categories and subcategories.

4.1. Characteristics of the Participants

The interview was conducted with a representative sample of 62 education professionals who hold the position of school head in Andalusia.

Table 4 shows the demographics and characteristics of the participants. The participants were mostly male (60%), holding a position as headmaster (46.77%) and with a length of service of 3 to 5 years (46.77%).

Table 4.

Interview script.

4.2. Responses to the Interview Topics

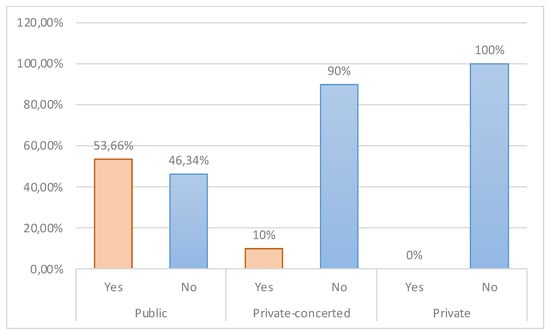

All interview participants were asked about the definition of the concept of students with special educational needs. Among the main results, we found that only 37.1% of the interviewees defined the concept correctly, and 62.9% defined it incorrectly. The incorrect definition of the concept SEN was generalised by the participants in all provinces.

If we analyse the response according to the variable “Ownership of the school”, 80% of those interviewed in public schools know the meaning of the SEN concept. On the other hand, participants from privately owned schools (100%) provided the highest percentage of incorrect answers, as can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Ownership of the school and concept of SEN.

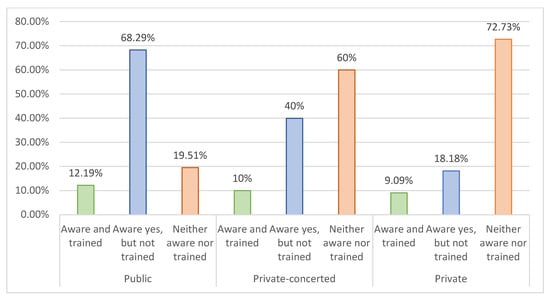

Considering the results, the participants were asked whether they believed that the special education teachers in their schools were aware of and trained in the use of technologies for working with students with special educational needs. In this sense, 54.84% of the respondents acknowledged that special education teachers are aware of, but not trained in the use of technologies for students with special educational needs, compared to 32.26% who stated that teachers are neither trained nor prepared for their implementation. Only 12.9% of the participants consider that special education teachers are trained in digital competences.

The results are similar if we analyse the responses according to the province in which the participants’ schools are located. However, if we analyse the responses according to the school ownership variable (Figure 3), the schools with the highest percentage of responses in the category “neither aware nor prepared” were private schools (72.73%), while public schools had the highest percentage of positive responses in the category “aware and prepared” (12.19%).

Figure 3.

Level of teacher awareness and training according to school ownership.

On the other hand, regardless of the conceptual notions held by the interviewees, the participants had the opportunity to argue the factors or barriers that underpin the low level of awareness and training in digital competences among special education teachers in Andalusia, as shown in Table 5. Among the main reasons mentioned by key informants, the following stand out: the scarce training offered (25%), teachers’ attitude (22%) and economic factors (16%).

Table 5.

Barriers to digital competence.

“In my opinion, teachers are interested in training courses, but I think that there is insufficient training on specific aspects of the use of technology with learners with educational needs.”(INT.32)

“Honestly, I think that teachers are getting more and more tired and stressed, and they don’t have the time or the desire to train.”(INT.53)

“I imagine that one of the barriers is financial, as the development of such specific courses is usually offered by private institutions, and not all teachers are willing to invest in so many courses.”(INT.04)

After finding out the level of awareness and digital training, as well as the barriers to their training, that special education teachers have, it is considered essential to check the degree of development of training experiences on technologies applied to students with special educational needs that are being carried out according to the opinion of those interviewed. In this sense, 72.58% of those interviewed recognise that training experiences focused on the use of technologies for students with educational needs are scarce or non-existent, or that they focus on the general use of technologies without considering the diversity of students, compared to 27.42% who consider the opposite to be true.

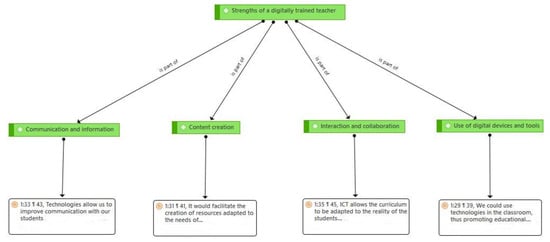

With regard to the development of training experiences depending on the provinces of Andalusia, the data do not vary considerably, since in the provinces of Granada, Malaga and Seville, the participants indicated that no training experiences are developed (75%, 70% and 68.75%, respectively). Likewise, as shown in Figure 4, the interviewees showed that the digital competence of special education teachers presents numerous strengths in educational quality, highlighting, mainly, that the use of technologies as didactic resources in the teaching-learning process depends on their level of digital training (43%) or for the creation of specific materials and contents for students (35%). To a lesser extent, but no less important, their digital training improves communication with students (13%), as well as their interaction and flexibility of teaching students (9%).

Figure 4.

Semantic network with empirical evidence of the category “Strengths of a digitally trained teacher”.

“Teachers feel insecure about using technology in their teaching practice; if they had this acquired competence, technology would be an essential resource in the classroom.”(INT.33)

“Knowing how to use technology appropriately allows teachers to adapt their materials and resources to students with educational needs.”(INT.57)

However, we consider it necessary to know which educational institutions develop the fewest training activities related to the use of technologies for students with educational needs. In this sense, those interviewed from privately owned centres (100%) and those interviewed from privately concerted centres (90%) are the ones who claim that such training experiences are not offered or carried out. However, 39.02% of the participants from the public centres confirm the existence of training activities related to this subject.

“There are training activities related to the use of technology with these pupils, although most of them are not very specific.”(INT.2)

“This type of training is not developed, they are training courses with more general content, although I think it is necessary to develop these training experiences, not only for teachers, but also for the pupils themselves and their families.”(INT.41)

“The offer of training courses is made at the provincial level, but not taking into account the needs of a particular school. Each school can take part in these courses, for its teachers, but most of them are not aimed at the field of special education as they are addressed to all teachers in the school.”(INT.49)

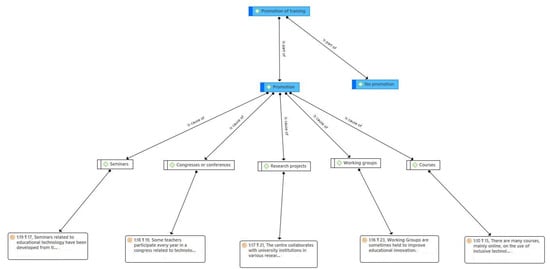

Based on the above context, it is considered necessary to find out whether and how schools facilitate training experiences and how they promote such training. The participants show that 67.74% of the schools try to promote and offer, through different means, training activities for special education teachers, compared to 32.36% who indicate that they do not promote it enough. Among the results, as shown in Figure 5, there is a high tendency towards courses (34%), both face-to-face and virtual, on technologies in special education. Seminars (28%), congresses or conferences (16%), research projects (14%) and working groups (8%) also stand out among the responses.

Figure 5.

Semantic network with empirical evidence of the category “Promotion of training”.

“From the centre, we ask the Teacher Training Centre to offer these courses, either face-to-face or distance, as they are the ones they offer the most in their calls for applications.”(INT.58)

“Yes, if it is promoted. We try, at least here in our centre, to select courses that address the digital inclusion of all students, as well as collaborating in different research projects.”(INT.32)

Once it has been verified that the educational centres in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia ensure that digital training for special education teachers is offered and promoted, the training priorities that should be included in these courses are mentioned. Key informants mention that, as shown in Table 6, it is considered a priority for training activities to address different didactic strategies for carrying out curricular adaptations supported by technology (26%), as well as to learn about different digital tools, devices, and software for these students (22%).

Table 6.

Priorities for digital training.

5. Discussion

Considering the results presented in the previous section, the aim is to answer the research questions posed in the study:

- RQ1. What are the perspectives of the school management team on the level of digital competence of special education teachers in Andalusia?

It is essential that teachers have an adequate level of digital competence; however, the research participants perceive a low level of digital awareness and training of special education teachers in Andalusia, findings that coincide with previous research [13,20]. From this perspective, it has been pointed out that teachers’ digital training is closely linked to the use they make of them in their teaching practice, as this is one of the most influential professional teaching competences in education today [31]. Therefore, if one of the Sustainable Development Goals is to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all students [32], special education teachers must improve their training in digital competences.

This training will enable them to acquire the digital skills needed to develop new methodological strategies that include the use of technologies [33]. In other words, effective outcomes from the use of technology depend on the level of preparation and self-efficacy of educators. However, this requires a prior awareness of the value of integrating technology in special education classrooms, as well as a willingness to use technology to instruct students with special educational needs.

- RQ2. Does the ownership of the school condition the level of digital competence of special education teachers as perceived by the school management team?

The participants in the research indicated that special education teachers are generally aware of the value of technology in education, but not trained in the use of technologies [34]. However, if we analyse the responses according to the variable “Ownership of the school”, we can conclude that, in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia, this variable does condition the level of digital training of special education teachers, which is in line with previous studies [35].

Along these lines, the participants from private schools stand out as those with the highest percentage who consider that their teachers are neither trained nor aware of the use of these technologies. These findings may be since private schools are the schools that offer the fewest training experiences and initiatives for special education teachers related to digital competence. These findings reflect the importance of focusing on the achievement of continuous teacher training, as this is what will make it possible to offer quality education to all students and to achieve an efficient use of technological resources [36].

- RQ3. What are the perspectives of school heads on the challenges of digital competence of special education teachers (i.e., what actions and strategies are associated with the promotion and development of digital training experiences)?

One of the key factors that guarantee the successful implementation of educational technology is the teacher’s own digital competence [37]. However, the reasons for the low level of digital awareness and preparation of special education teachers are related to aspects such as the scarcity of training provision, the attitude of teachers and economic factors.

The rapid updating of technological tools makes the resources available in the classroom obsolete, so that, nowadays, continuous training in digital competences has become a priority requirement for teachers in order to achieve an efficient use of technological tools [38].

Furthermore, the scarcity of specific courses offered by educational institutions or teacher training centres means that teachers must pay for their training through courses, master’s degrees, or congresses, which entail a high financial cost each year. This finding is consistent with those obtained by González et al. [39] and Ramírez et al. [40].

The participants in the research point out the importance of promoting the development of training experiences through courses, seminars, congresses and/or conferences. These training activities should mainly include content related to didactic strategies for carrying out curricular adaptations supported by technology, as well as learning about different digital tools, devices, and software to respond to the educational needs of these students.

The acquisition of digital competence is fundamental, as a digitally competent teacher will be able to integrate technologies into the classroom on a daily basis, respond to the needs of their students and create new content through technology. Therefore, it is necessary for teachers to improve their training in digital competence to make the inclusion of technology in special education classrooms a reality.

6. Conclusions

The use of technology has become a fundamental resource for the education of all learners. However, in the context of special education, experiences are more limited. This lack of digital experiences in special education classrooms is due to the limited technological resources in schools and the lack of training for special education teachers. In this study, participants reported that the main barriers limiting digital competence training, being on the one hand due to limited training experiences, as well as personal issues such as attitude, lack of time or finances.

The findings suggest that schools take measures to reduce the digital divide in the context of special education by (1) improving infrastructure and acquiring digital resources and devices, (2) developing new digital training experiences according to the needs of special education teachers and (3) promoting and rewarding the digital training of schoolteachers.

6.1. Implications for Practice

These findings will have implications for practice. The improvement of digital competence as well as the acquisition of digital resources in the school will serve as significant enablers for the integration of technologies in the special education classroom. Using technologies with these students with educational needs will enable students to achieve their educational goals. Likewise, the findings can be used by the Education Administration for decision-making in the development of training plans for both initial and in-service training of special education teachers.

6.2. Future Lines of Research

As future lines of research, the following are proposed: to carry out studies of good practices in the incorporation of technologies for students with educational needs using information-gathering techniques such as non-participant observation and in-depth interviews; to extend the informants to those responsible for teacher training, special education teachers and parents of students with special educational needs; and to study in depth the specific problems that special education teachers have in incorporating technologies for students with educational needs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.-R. and J.F.-C.; methodology, M.M.-R.; software, M.M.-R. and J.F.-C.; validation, M.M.-R.; formal analysis, M.M.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.-R.; writing—review and editing, M.M.-R.; funding acquisition, M.M.-R. and J.F.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economics and Competitiveness within the State Plan for the Development of Scientific and Technical Research of Excellence 2013–2016 (DIFOTICYD EDU2016 75232-P) and VII PPIT-US of University of Seville.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the fundamental principles of research integrity were respected in accordance with the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Seville.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of a doctoral thesis developed within the framework of the Doctoral Programme in Education at the University of Seville (Spain).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Basantes-Andrade, A.; Cabezas-González, M.; Casillas-Martín, S. Digital Competences Relationship between Gender and Generation of University Professors. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2020, 10, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redecker, C.; Punie, Y. Digital Competence of Educators: DigCompEdu; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; Available online: https://cutt.ly/4N3sw14 (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Consejería de Desarrollo Educativo y Formación Profesional (Junta de Andalucía). Decreto 93/2013, de 27 de agosto, por el que se regula la formación inicial y permanente del profesorado en la Comunidad Autónoma de Andalucía, así como el Sistema Andaluz de Formación Permanente del Profesorado. Boletín Of. Junta Andal. (BOJA) 2013, 170, 1–142. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2013/170/1 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Consejería de Desarrollo Educativo y Formación Profesional (Junta de Andalucía). Resolución de 1 de septiembre de 2022, de la Dirección General de Tecnologías Avanzadas y Transformación Educativa, por la que se determina el desarrollo de las líneas estratégicas de formación del profesorado establecidas en el III Plan Andaluz de Formación Permanente del Profesorado y la elaboración de los proyectos de formación para el curso 2022/2023. Boletín Of. Junta Andal. (BOJA) 2022, 173, 1–5. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2022/173/21 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Alarcón, R.; Pilar Jiménez, E.; Vicente-Yagüe, M.I. Development and validation of the DIGIGLO, a tool for assessing the digital competence of educators. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 2407–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Barzabal, M.L.; Martínez Gimeno, A.; Jaén Martínez, A.; Hermosilla Rodríguez, J.M. La percepción del profesorado de la Universidad Pablo de Olavide sobre su Competencia Digital Docente. Pixel-Bit Rev. Medios Educ. 2022, 63, 35–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebot, M.Á.L.; Cosentino, V.V.; Esteve-Mon, F.M.; Segura, J.A. Diagnostic and educational self-assessment of the digital competence of university teachers. Nord. J. Digit. Lit. 2021, 16, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toktamysov, S.; Berestova, A.; Israfilov, N.; Truntsevsky, Y.; Korzhuev, A. Empowerment or Limitation of the Teachers’ Rights and Abilities in the Prevailing Digital Environment. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. (IJET) 2021, 16, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, R.; Buenestado-Fernández, M.; Ramírez-Montoya, M.S. Assessment of Digital Teaching Competence: Instruments, results and proposals. Systematic literature review. Educación XX1 2023, 26, 273–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Batanero, J.M.; Román-Graván, P.; Montenegro-Rueda, M.; López-Meneses, E.; Fernández-Cerero, J. Digital Teaching Competence in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb, A. Assistive technology in special education and the universal design for learning. TOJET Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2014, 13, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Yelland, N. An Investigation of preservice early childhood teachers’ adoption of ICT in a teaching practicum context in Hong Kong. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 2017, 38, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istenic, A.; Bagon, S. ICT-supported learning for inclusion of people with special needs: Review of seven educational technology journals, 1970–2011. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2013, 45, 202–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4; Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities for All; UNESCO: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–83. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656 (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Morales, P.T.; Llorente Cejudo, M.C. Formación inicial del profesorado en el uso de las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación (TIC) para la educación de personas con discapacidad. Rev. Educ. Digit. 2016, 30, 135–146. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/DER/article/view/317378 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Fernández Batanero, J.M.; Román Graván, P.; Siles Rojas, C. ¿El profesorado de Educación Primaria de Cataluña (España) está formado en TIC y discapacidad? Rev. Educ. Digit. 2020, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Batanero, J.M.; Montenegro Rueda, M.; Fernández Cerero, J.; García Martínez, I. Assistive technology for the inclusion of students with disabilities: A systematic review. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2022, 70, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, G.H.; Tejedor, F.J.; Calvo, M.I. Meta-Análisis sobre el efecto del Software Educativo en estudiantes con Necesidades Educativas Especiales. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2017, 35, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, A.; Vázquez-Cano, E.; Belando, M.R.; López, E. Análisis bibliométrico del impacto de la investigación educativa en diversidad funcional y competencia digital: Web of Science y Scopus. Aula Abierta 2019, 48, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A. Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research; Sociology Press: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Andreu-Andrés, M.A.; Labrador-Piquer, M.J. Formación del profesorado en metodologías y evaluación. Análisis cualitativo. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2011, 9, 236–245. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Batanero, J.M.; Rodríguez-Martín, A. TIC y diversidad funcional: Conocimiento del profesorado. EJIHPE Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2017, 7, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory. A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J. Qualitative Research Design. An Interative Approach, 3rd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Abascal Fernández, E.; Grande Esteban, I. Análisis de Encuestas; Escuela Superior de Gestión Comercial y Maketing (ESIC): Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Batanero, J.M.; Tadeu, P.; Cabero, J. ICT and disability. Design, construction and validation of a diagnostic tool. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2018, 9, 332–350. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Ramírez, M.; Martínez Cepena, M.C. Origin and development of an index of expert competence: The k coefficient. Rev. Latinoam. Metodol. Investig. Soc.—ReLMIS 2020, 19, 40–56. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Bases de la Investigación Cualitativa. Técnicas y Procedimientos para Desarrollar la Teoría Fundamentada; Universidad de Antioquia: Medellín, Colombia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss, J.L. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- López-Gil, M.; Bernal-Bravo, C. El perfil del profesorado en la Sociedad Red: Reflexiones sobre las competencias digitales de los y las estudiantes en Educación de la Universidad de Cádiz. Int. J. Educ. Res. Innov. (IJERI) 2019, 11, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos Torres, D.I. Contribución de la Educación Superior a los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible desde la docencia. Rev. Española Educ. Comp. 2021, 37, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello, I.; Cascales, A. Las TIC y las necesidades específicas de apoyo educativo: Análisis de las competencias tic en los docentes. RIED 2015, 18, 355–383. [Google Scholar]

- Surajundeen, T.B.; Ibironke, E.S.; Aladesusi, G.A. Special Education Teachers’ readiness and self-efficacy in utilization of assistive technologies for instruction in secondary school. Indones. J. Commun. Spec. Needs Educ. 2023, 3, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Batanero, J.M.; Román Graván, P.; El Homrani, M. TIC y discapacidad. Conocimiento del profesorado de educación primaria en Andalucía. Aula Abierta 2017, 46, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegalajar Palomino, M.C. Actitudes del docente de centros de educación especial hacia la inclusión educativa. Enseñanza Teach. Rev. Interuniv. Didáctica 2014, 32, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero-Almenara, J.; Barroso-Osuna, J.; Palacios-Rodríguez, A. Estudio de la competencia digital docente en Ciencias de la Salud. Educ. Médica 2021, 22, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, E.; Sola, T.; Ortega, J.L.; Marín, J.A.; Gómez, G. Teacher training in lifelong learning. The importance of digital competence in the encouragement of teaching innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; De Pablos, J. Factores que dificultan la integración de las TIC en las aulas. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2015, 33, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, E.; Cañedo, I.; Clemente, M. Las actitudes y creencias de los profesores de secundaria sobre el uso del Internet en sus clases. Comunicar 2011, 19, 47–155. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).