Abstract

The Norwegian Public Health Act (PHA) mandates municipalities to integrate a systematic, knowledge-based, cross-sectoral approach aimed at levelling the social gradient in health. This study aimed to describe and analyse how the intentions of the PHA are addressed in municipal plans and project-planning documents. A document analysis of municipal plans and project documents extracted from four municipalities in Central Norway was employed and complemented with deductive, qualitative content analysis. Findings indicate awareness of public health work as a whole-of-municipality responsibility. Systematic knowledge-based processes that make use of relevant data in planning and decision-making processes are described across municipality projects and plans. Multisectoral working groups are set up at a project level; however, opportunities for further improvements arise in respect to the anchor of these structures and systematic knowledge-based working procedures in the wider municipal context. Public health process aims (systematic knowledge-based approach, cross-sectoral governance) receive more attention than outcome aims (health equity) in both program documents and municipal plans. Only very rarely does the document hold operationalizations of how to achieve health equity. As such, effort placed on cross-administrative levels and sectors to promote structures for health equity is still needed.

1. Introduction

In the context of public health and health promotion, local authorities and communities play a key role in developing and implementing approaches in line with national and international aims and intentions. Local planning systems appear as important means to ensure that local efforts contribute to the realization of overall policy aims, such as reducing social health inequality. While measures are developed and anchored locally, regional, and national authorities have a significant role in facilitating and supporting local work. In addition to the distribution of material resources, legal and strategic requirements also play a significant role in how public health work is carried out across municipalities [1,2,3].

The Norwegian strategy to reduce social inequalities is expressed in the Public Health Act (PHA), which took effect in 2012 [1,4]. Both the strategy [1] and the PHA [4] emphasize a holistic, broad cross-sectoral approach with an explicit focus on the social gradient and the principle of “proportional universalism”. This is also supported by the Planning and Building Act of 2008, which sought to strengthen cross-sectoral anchoring, promote public health, and counteract health inequalities [5]. The PHA was developed as a top-down strategy at the national level as part of the Norwegian Coordination Reform [6]. The main motivation for the reform was to encourage municipalities to expand local primary health care services to include holistic patient pathways, more prevention, better user co-determination and sustainable development. The PHA is thus explicitly underpinned by the principle of “health in all policies” (HiAP) [1,3,4] and aims to bestow a broad basis for the coordination of public health work both horizontally (across various sectors and actors) and vertically (between authorities at local, regional, and national levels) [3,7]. By recognizing that policies in all sectors influence population health, and vice versa, the act gives Norwegian municipalities, as planning authorities, community developers, and service providers, the main responsibility of safeguarding the overall health and living conditions of the population. Consequently, local planning systems are important means of ensuring that the overall policy aims are being implemented locally [4,5,8,9].

However, despite a clear ambition to reduce social health inequality, evaluations of the Coordination reform suggest that health inequalities were hardly mentioned [2,10]. Studies also indicate a lack of consistency between intentions and implementation in the municipalities′ subsequent work [2,9,11,12,13]. Although the aim of reducing social inequalities in health is often included in general policy recommendations, municipal public health plans have often been characterized by individual, lifestyle-centred approaches initiated by the health sector [9]. Correspondingly, evidence suggests that approaches targeting only the most disadvantaged populations are unlikely to be effective in levelling-up the social gradient in health and may even contribute to an increase in health inequalities [2,9,13]. Fifteen years have passed since the national strategy to reduce social inequalities in health was launched [1]; however, the challenges are still apparent. Health inequalities in Norway are growing, yet less attention is devoted to determining factors such as living conditions, housing, labour market, education, and economic circumstances [14]. This calls for a recognition of factors beyond the domain of the health sector as suggested by the Norwegian Council on Social Inequalities in Health and emphasised in the recent rapid review of inequalities in health and wellbeing in Norway since 2014 [15,16].

Based on a request provided through the Public Health Report of 2015 [17], a ten-year commitment to enhancing municipal public health work was set up in 2017 by the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS) and the Ministry of Health and Care Services to combat social health inequalities. The national initiative—Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities (2017–2027)—aims to contribute to a long-term strengthening of the municipalities′ efforts to promote the population′s health and quality of life, with a particular focus on children and adolescents, mental health, and substance use [18].

1.1. Regional and Local Implementation of Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities

In conjunction with the national program, the local implementation of the Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities in Central Norway put a special emphasis on working methods for knowledge-based cross-sectoral public health work [19]. All thirty-four participating municipalities had to go through a formal application process to become part of the program. Participating municipalities had to apply The Trøndelag Model for Public Health Work as a working method [20,21,22]. The model [20] is strongly committed to the Norwegian Public Health Act [4] and offers a systematic step-by-step working method that integrates and moves beyond sectors and profession-specific approaches when implementing plans into effective public health initiatives. The model provides municipalities with guidelines that adhere to international principles of good governance in public health work, follow key principles for health promotion, and is found useful in different contexts where the aim is to improve practical solutions [20,21,22,23,24].

The context of the Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities offers a unique opportunity to explore local planning and the intentions instructed by the PHA. As such, we pay attention to local planning by describing and analysing if and how the intentions of the PHA [4] are visible in municipal plans and project planning documents. More specifically, we want to explore how the intentions of systematic knowledge-based approaches, cross-sectoral governance (process aims), and health equity (outcome aim) are visible in plans and project documents extracted from four Norwegian municipalities. In doing so, we address the following research questions (RQs):

- RQ1: Are the intentions included in municipal and project plans?

- RQ2: How are the intentions described (operationalized) and anchored in municipal and project plans, and are there differences across municipalities in this regard?

- RQ3: How is the relationship between process (knowledge-based approaches, cross-sectoral governance) and outcome (health equity) described in the documents?

1.2. Municipal Planning

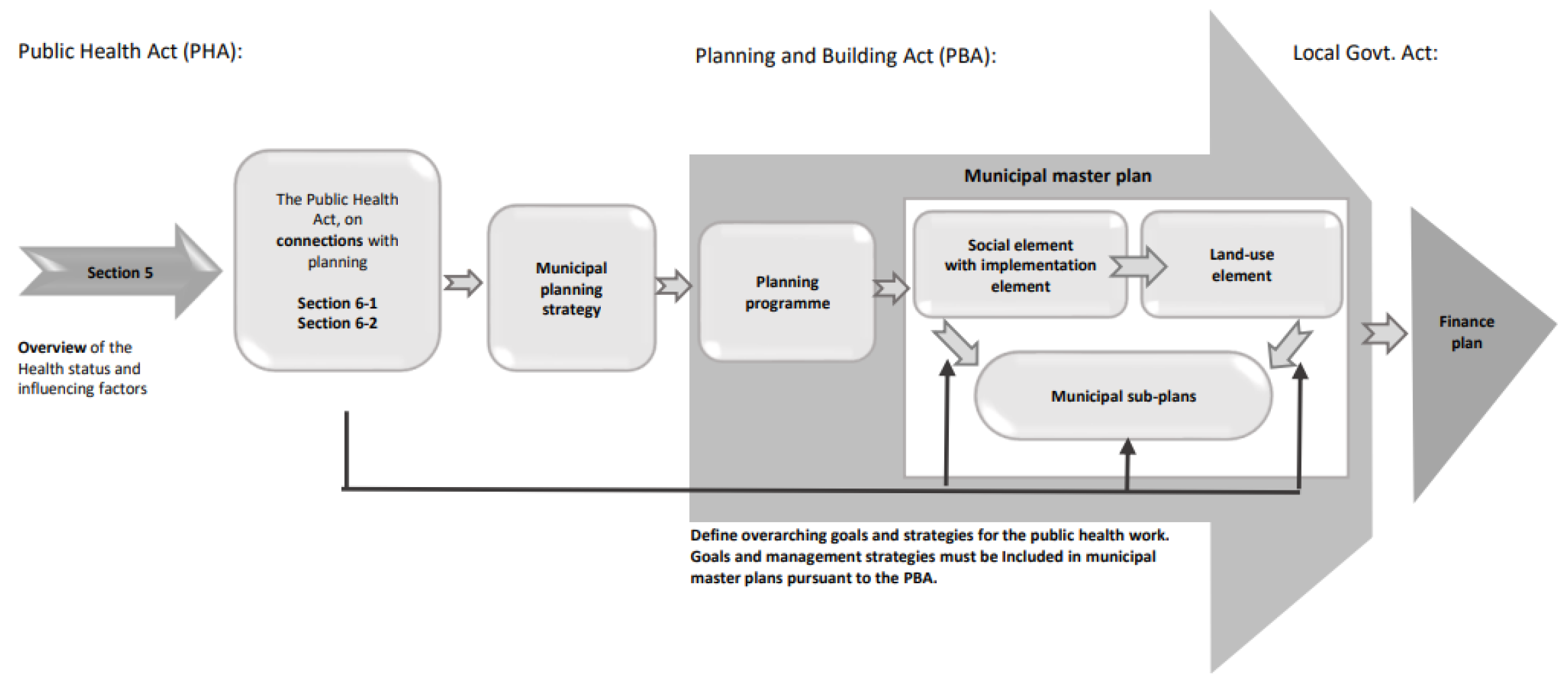

The necessity for collaboration and coherence across government sectors, policy areas, disciplines, and levels to improve public health is evident and can be achieved only by placing efforts into anchoring public health in the municipality’s planning system [19]. Exploring municipalities’ project documents and plans enables a deeper insight into whether and how the intentions of the PHA may have guided the municipalities planning for promoting health and health equity. In the following, we present a brief description of the PHA and its role in the Norwegian plan system (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1.

Model visualizing the municipal plan process and the relatedness between the Public Health Act and the Planning and Building Act (Adapted from [25,26]).

The Plan and Building Act (PBA) [5] is the overall framework for planning in municipalities. Planning eases the sound design of built environments, sound local environments, and sound upbringing and living conditions, as well as promoting public health, counteracting social inequalities in health, and helping prevent crime. Municipalities must prepare a planning strategy at least once in each election period, clarifying the municipality′s strategic choices for the planning period. They must also have a municipal master plan (MMP) that includes a social element with implementation and land-use elements [25]. In addition, the municipalities are free to prepare municipal topical sub-plans. The MMP is based on the municipal planning strategy and should promote municipal, regional, and national goals, interests, and functions. Furthermore, the PHA obliges municipalities to help ensure that health considerations are taken care of by other authorities and businesses. In other words, the municipalities must take care to involve relevant groups in the preparation of the municipal planning strategy (MPS) and MMP, while also ensuring that other actors take account of various considerations about public health work.

Meeting these obligations requires interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral collaboration. As part of the systematic public health work, municipalities are obliged to develop an overview of public health (OPH) as the basis for the municipal planning strategy. In the MMP (social element, land-use element, and municipal sub-plans), the municipality shall also define overarching goals and strategies for public health work that are effective in solving the municipality′s specific public health challenges. This also implies that spatial and project plans should be aligned with overarching documents and aims. Figure 1 illustrates the relationships and emphasizes the internal hierarchy of planning documents.

2. Methodology

To explore how the intentions of the PHA—delegating local responsibility for systematic knowledge-based cross-sectoral governance (process aim) and for improving health equity (outcome aim)—are addressed in municipal plans and project documents, a document analysis design [27] was employed. Municipal plans and project documents were extracted from four municipalities. All included documents had to be developed and published within the period of the Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities and represent juridically committed documents. Data extraction and analyses were conducted by the first, second, and last authors from October 2022 to January 2023. A total of twenty-two documents were included in the analysis:

- 10-year national and regional plan (Central Norway) for Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities 2017–2027 (two documents).

- Applications and municipal project plans related to participation in Program for Public Health work in Municipalities (2017–2027): (eight documents).

- Municipal plans in line with the Norwegian plan system [25,26]: Municipal Planning Strategy (MPS), Municipal Master Plan (MMP) and Municipal Action Plan (MAP) (12 documents).

2.1. Data Sources and Characteristics of Municipalities

The included municipalities (see Table 1 below) had to take part in the regional Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities in Central Norway. Further, they should represent heterogeneity in terms of urban and rural settlements, as well as population size.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the four municipalities from which the included documents are extracted.

2.2. Operationalisation and Analysis

A deductive content analysis of included documents was conducted to address the research questions [29]. Content analysis involves the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and finding themes or patterns, and the data collection method aims to reach data saturation [30]. The analyses were conducted in two distinct steps: first, the frequency and content of central terms across included documents were assessed to gain insights into how the themes are operationalized and applied (RQ1/2); second, we analysed how each of these themes was applied and followed up within each of the included municipalities (RQ2/3). The following is a detailed description of the two steps (operationalization and analyses) conducted to address the research questions:

2.2.1. Step 1

Operationalisation of the Themes for Document Search

For the initial search and the first step of analysis, each of the three themes (systematic knowledge-based approaches, cross-sectoral governance, and health equity) was operationalized according to the PHA [5] to generate search words.

‘Systematic knowledge-based approaches’ was operationalized using the following search words: systematic, system, long-term, knowledge, knowledge-based, knowledgebase, data, anchoring, and anchored.

‘Cross-sectoral governance’ was operationalized using the following search words: cross-sectoral, multi-sectoral, collaboration, and across-, sectors.

‘Health equity’ was operationalized using the following search words: inequality, equality, levelling, gradient, and equity.

To ensure relevance, search words were only included in further analysis if they occurred in the thematic context of health equity, the social gradient in health, or other health-related contexts. In addition, the terms “social sustainability”, “health promotion”, and “public health” were included in the search even though the PHA does not explicitly link these to either of the search terms. These terms were included to find other potential concepts relating to our themes of interest.

Analysis

In this first step of the analysis, we applied a direct content analysis of the three central themes (systematic knowledge-based approaches, cross-sectoral governance, and health equity) across the type of document and municipalities to gain an overall picture of whether terms are applied and how they are operationalized in the planning documents. Documents were coded according to theme, followed by a word search to find the selected themes’ frequency. Then, each term was analysed with respect to (a) explicit operationalization/definitions given in the documents, and (b) the context(s) (line, sentence, or paragraph) in which it clarified the relational aspects of the terms’ content regarding other central terms and concepts. Given the heterogeneity of the content of the included documents, these methods were the most proper for displaying the different results from the four Norwegian municipalities’ included documents.

2.2.2. Step 2

Operationalization

For the next step of the analysis, operationalizations were refined in line with the above-described initial content analysis. Systematic knowledge-based approaches include matters of anchoring and working knowledge-based and were assessed via tracking: how intentions were followed across documents; whether terms and priorities were aligned in the municipal context; and whether and how themes were addressed in plans relevant to enable actions. The development of a local knowledgebase (OPH) and the application of the OPH to define aims and activities were also assessed.

Cross-sectoral work was operationalized as the establishment of cross-sectoral forums and looked at how these were framed and anchored in the municipal context (e.g., closely linked to the Program for public Health Work in Municipalities or established as a regular activity beyond the specific approach). Lastly, in order to analyse how health equity was addressed in municipalities, we assessed (a) whether health equity was established as the main goal, (b) whether this was followed up under prioritization of efforts; (c) whether health equity was operationalized/linked to the social determinants of health, and/or (d) whether it was translated into approach-specific aims (such as levelling-up a deprived target group).

Analysis

In the second step of the analysis, we conducted a contextual content analysis by assessing and analysing how themes (intentions) were followed up and applied within each of the included municipal contexts. Emerging findings and themes were compared across municipalities to assess differences in how the planning documents were utilized across municipalities. A special focus was kept on how processes and process aims are linked to the main aim of increased health equity throughout included documents.

In order to carry this process out, we gathered all documents from each municipality in analytical clusters, representing a specific municipal context. We then defined how the different types of documents contributed to defining the municipal context according to the above-described hierarchy in the planning system (see Section 1.2). This enabled us to phrase expectations about how the documents would inform each other and how they facilitate actions and activities. Next, we tracked how each theme was addressed within each of the municipalities across documents, to gain a coherent picture of how the central themes are addressed and applied in the documents that define aims and approaches for municipalities’ public health work.

Together, these analysis steps supplied an overview of how the various documents emphasized and operationalized the intentions of the PHA. Quotes from the documents (in quotation marks) are used to provide concrete examples of what is claimed.

3. Results

Following the procedure during analysis, we first present an overview of the frequency of the themes of systematic knowledge-based approaches (process aim), cross-sectoral governance (process aim), and health equity (outcome aim) in municipal plans and project documents (Table 2) (RQ1). Secondly, findings on how the intentions are described (operationalized) and anchored in municipal and project plans, and differences across municipalities in this regard, are presented (RQ2). Lastly, the relationship between process (knowledge-based approaches, cross-sectoral governance) and outcome (health equity) aims described in the documents is presented (RQ3).

Table 2.

Frequency of the themes of systematic knowledge-based approach, cross-sectoral governance, and health equity in municipal plans and project documents.

3.1. RQ1: Are the Intentions Included in Municipal and Project Plans?

As shown in Table 2, the intentions of the Public Health Act are included in various manners across municipal plan documents and project plans. Among the three search themes, the Systematic knowledge-based approach is the concept most often referred to across documents, predominantly in project applications and project plans. Cross-sectoral governance is used across municipal and project documents, though more frequently in project applications and project plans compared to municipal plan documents. Health equity is the theme least referred to, both when it comes to project documents and municipal plan documents: it is also treated less consistently across the documents. Only one municipality included a systematic knowledge-based approach, cross-sectoral governance, and health equity as themes across all municipal and project plans.

3.2. RQ2: How Are the Intentions Described (Operationalized) and Anchored in Municipal and Project Plans, and Are There Differences across Municipalities in This Regard?

Systematic knowledge-based and cross-sectoral processes in defining and developing measures and aims are described consistently throughout the included documents. There was variation across the project and plan documents in how they approached the concepts: while plans primarily signalled an ambition to work knowledge-based and systematically, project documents would go further into describing and exemplifying their intended procedures to work systematically. Some of the municipal plans would touch upon the issue from a rather broad angle, showing their efforts to work more systematically and through a knowledge-based approach in general, across domains. Awareness about the importance of knowledge-based approaches was clearly visible, and described as a goal in itself:

“Constant new knowledge and large amounts of information place new demands on employees to keep professionally updated. A goal for all professional practice is that it must be based on the best available knowledge—so-called knowledge-based practice”.

Several of the project documents refer to the Trøndelag Model for Public Health Work [20] in describing their work procedure based on local knowledge when planning their measure. Systematic use of available and relevant data in planning and decision-making processes is described across municipalities’ projects and plans:

“…it has been decided that the knowledge base on public health (the overview document on public health and influencing factors) shall be used as a basis for the formulation of goals and measures at all levels of the municipality’s planning”.

All municipalities have developed a systematic OPH and attention is devoted to determining factors for health equity such as for example living conditions, housing, labour marked and education. However, only very rarely did the documents hold detailed operationalizations of these factors. Moreover, differences occur based on whether general/national and/or local knowledge is utilized. Variations also occur concerning how the OPH is subsequently applied, especially with respect to developing aims and measures in line with local public health challenges.

Likewise, applying cross-sectoral approaches could simultaneously be described as an aim or as an approach: The latter operationalization was more often followed by a more substantial plan for how to facilitate cross-sectoral interaction and collaboration. In some municipalities, documents described the cross-sectoral working processes applied to create the documents as:

“In the preparation of this strategy, the public health profile has been an essential document, together with input from business managers and an appointed cross-sectoral administrative project group”.

Cross-disciplinary working groups were set up in all four municipalities in relation to the Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities. Moreover, in line with guidelines for participation in the Program for Public Health work in Municipalities, documentation shows that the project applications and project plans within the four included municipalities were anchored administratively and politically (considered by the municipal council). However, descriptions of the extent to which these groups were sufficiently anchored in the administrative structure and across sectors responsible for implementing the PHA varied across municipalities.

Achieving better health equity is a pre-defined goal in the PHA, as well as a main goal for the Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities. Document analysis reveals that this term was mostly used when referring directly to the project; however, it was still emphasized as an overall aim or ambition either in the municipality’ plans or the program project or in both.

All four municipalities have public health as one of their prioritized areas for community-development. However, the terminologies of equity, social inequalities, and levelling the social gradient are often not directly used, and are instead referred to as, for example, “including all”, “participation for all”, “inclusive local communities for all”, “all groups of society”, “all children and young people have the opportunity to participate”, in the respective documents. In addition, health equity was referred to as a requirement provided by the PHA and the Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities and was important for the direction taken as regards their project/public health work. Some of the measures selected and described in a municipal plan and project documents are universal and population-oriented, with the intention of levelling the social gradient.

Across the municipalities, reducing social health inequalities and levelling the social gradient in health are described in a more consistent manner in the municipal project plan compared to the MMP. While health equity is established as an aim in the MMPs, the project applications more explicitly address how to improve mental health in children and adolescents, thereby contextualizing the overall aim within the context of the project.

Awareness about a life course approach and how the meaning arenas of daily living (such as child health centres, day-care, schools, and leisure time activities) play in respect to reducing social inequalities are, however, described across the municipal plans:

“Giving children and young people good conditions for growing up will have good effects for decades to come. Child health centres, kindergartens, and schools have a special position in health promotion as they meet all children at an early stage”.

Nevertheless, in only one of the included municipalities did this awareness become clearly visible in subsequent action plan to ensure dedicated resources.

All in all, the findings indicate that process aims (systematic knowledge-based, cross-sectoral approaches) are implemented systematically across all types of documents, while health equity (outcome aim) is treated in a less consistent manner (compare RQ1). Operationalizations of central terms are in line with the intentions of the PHA; however, major variations occur in respect to how these are anchored and are pursued in the local context. The overarching aim of health equity is linked to the social determinants in health and could be operationalized in relation to the context (project), including the specific target group (adolescents) and outcomes (better mental health).

3.3. RQ3: How Is the Relationship between Process (Knowledge-Based Approaches, Cross-Sectoral Governance) and Outcome (Health Equity) Described in the Documents?

In line with the above-described findings, three of the four municipalities describe process aims in more detail than they do outcome aims in both the program documents and municipal plans. Cross-sectoral governance, systematic knowledge-based decision-making, and anchoring of public health initiatives in municipal plans are described as critical for sustainable public health work but rarely linked to health equity explicitly. Among the process aims, cross-sectoral governance (process aim) was particularly framed as a necessary method to resolve and find good solutions to complex health problems.

“The entire project is based on cross-sectoral collaboration and show priority areas to reduce inequalities in basic social conditions. Measures can provide great benefits here because they can have a positive effect on the entire causal chain—they target the ‘causes of the causes’”.

Cross-sectoral governance was thereby described as both an ambition (outcome) and as a prerequisite for achieving the MMP intentions of levelling the social gradient in health (outcome aim), which is related to health equity. Meanwhile, the process aims of systematic and knowledge-based approaches were hardly linked to the main outcome (health equity) in the included documents. Instead, they seem to depend on cross-sectoral collaboration:

“Choosing specific measures on the basis of a broad and complex knowledge base is demanding and requires broad collaboration”.

Thus, process aims are seen as interrelated and equally dependent, which also reflects that they are understood both as approaches as well as desirable outcomes. Meanwhile, the degree to which cross-sectoral knowledge-based procedures (process aim) that ensure new knowledge were fed into plans that are relevant to enable actions on the determinants for health varied across municipalities.

Overall, process aims were often communicated independently from the outcome aim, and systematic knowledge-based processes were not directly tied to the outcome aim of improving health equity; rather, they were treated as an outcome aim. Although the process aims described relate to the intention of levelling the social gradient in health, only rarely did the documents hold detailed information on how the processes could contribute to achieving the overall aim of health equity. In some municipalities, project-specific operationalizations of the main aim were established and linked to process aims, such as involving adolescents in the development of measures to promote mental health in this target group.

4. Discussion

This article casts light unto how national authorities can support local public health work in municipalities through legal and strategic approaches by describing how the intentions of the Norwegian Public Health Act (PHA) can be tracked in municipal and project plans. One of the key features of the PHA is that it places accountability for public health work as a whole-of-government and a whole-of-municipality responsibility rather than a responsibility of the health sector alone [1,2,3,4,5]. Within the context of the National Initiative Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities (2017–2027), this study explored how the intentions of the PHA [4] regarding a systematic knowledge-based approach (process aim), cross-sectoral governance (process aim) and health equity (outcome aim) were addressed in municipal plans and project documents in four Norwegian municipalities in Central Norway. Specifically, we explored how these intentions of the PHA are included, operationalised, and anchored in projects and municipality plans, respectively, and how they can contribute to the development of local governance strategies and structures for systematic and multi-sectoral approaches.

Qualitative findings indicate that systematic cross-sectoral processes are considered a prerequisite for meeting the municipality’s public health challenges. These findings are related to the use of the Trøndelag Model of Public Health Work [20] and supply valuable insights into how project work was structured and expected to improve the context for subsequent systematic knowledge-based approaches in the municipality. Our results reveal awareness of public health work as a whole-of-government and a whole-of-municipality responsibility. The mandatory OPH supplies directions for municipal planning. The use of available and relevant public health data and the application of systematic knowledge-based planning and decision-making processes are described across municipality projects and plans. As such, municipalities acknowledge and ensure that determinants of health form a starting point for knowledge-based public health work. This is in line with earlier research suggesting that good and equitable public health depends on integrating health and its social determinants in all social and welfare developments through cross- and multisectoral actions [11,13,15,16,22].

Cross-disciplinary and cross-sectoral working groups are clearer in relation to specific measures within the Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities compared to the MMPs. This could be due to the explicit demand to describe how they plan to apply a knowledge-based approach and anchor their projects politically within the framework of the program requirements [19] as well as in the Trøndelag Model for Public Health Work [20]. However, the findings imply that municipalities have not yet sufficiently anchored cross-sectoral working processes in the administrative structure and across sectors responsible for implementing the intentions of the PHA [4]. This is in line with earlier findings claiming that there is lack of consistency between intentions and implementation in the municipalities, and that collaboration ties tend to be stronger within than across sectors [3,10,11,12,31]. This also illustrates how specific projects and approaches can make valuable contributions to fulfil the intentions described in MMPs and the PHA. To ensure that these contributions result in launching municipal systematic public health work, emerging insights and proven structures from the project should be included in later municipal management and planning, as described in the last step (step 7) of the working model applied [20,21,22]. This supports earlier studies showing that cross-sectoral structures that are part of the municipal organisation could ensure that knowledge and experiences are preserved and developed across approaches, and thereby, contribute to organizational learning [31,32,33]. As such, knowledge and emerging structures developed within the frame of the project can be integrated into the overall municipal organisation through bottom-up approaches that might help ease systematic efforts and a sustainable development over time. Due to the time scope of this research, no conclusion can be drawn on whether emerging insights influenced later plans and structures in the included municipalities. However, municipal plans are dynamic documents that are revised every four years. Following up this research by comparing how these issues are addressed in municipal plans after revision might yield valuable insights into whether this aim has been achieved locally.

Overall, there are promising traces of public health being integrated across MMP areas in line with the ambition to combat social inequalities in health, provided by the Norwegian council on Social Inequalities in Health and the recent review of inequalities in health and wellbeing in Norway [15,16]. In addition, prescribed procedural intentions by the PHA do provide the municipalities and counties with a useful foundation for systematic and long-term public health work across the sectors, based on the municipalities′ own planning and administration systems. However, how the prescribed procedural obligations of the PHA are applied in plan and project documents and where and how they became visible throughout analysis varied across municipalities; yet, this information was independent of municipal characteristics. Results also suggest that overall project plans are anchored in municipal plans and described in relation to ambitions and procedures that lie in municipal plans. This indicates that the specific project work is aligned with other municipal public health efforts and can contribute to achieving overarching goals, such as reducing social inequality in health.

Health equity is emphasised as an overall aim or ambition either in the municipalities plans or the program project or in both. However, only rarely would the documents contain operationalizations to achieve the health equity goal. Operationalizations were more often found in MAP than in the underlying MPS and MMP. This is in line with the respective roles included in documents related to municipal planning: while MPS and MMP define overall approaches and aims, action plans more closely relate to implementation processes that require knowledge about how to achieve these aims locally. However, the findings indicate that planning documents can be applied for different purposes across municipalities. This is also highlighted by cross-municipality variations in respect to tracing the concept of ‘health equity’ across levels of municipal plans (from the MPS over the MMP to the MAP). On the one hand, being able to trace the concept might indicate anchoring and systemic approaches. However, this might illustrate variations in the use of planning documents across municipalities. For example, one of the included municipalities developed a specific ‘public health plan’ with a detailed operationalization of the concept. However, while this plan was anchored politically, it did not stand for any legal plan requirements and was, therefore, not included in the analysis. This clearly illustrates that even if we can obtain some interesting insights by comparing how planning documents are anchored and used across municipalities, it is difficult to obtain a coherent picture of what is going on in the specific municipality solely based on plan document analysis.

In the documents linked to the project itself, health equity was most often addressed through the establishment of project-specific aims linked to addressing mental health in adolescents. This might be understood as a ‘translation’ or project-specific operationalization of ‘reducing health inequities’ by targeting a vulnerable group and resolving specific challenges based in social inequality. This could contribute to the establishment of a mutual understanding and make it easier to define sector- and level-specific responsibilities and aims. However, not linking these efforts to the overarching goal of health equity might increase the risk of unintended side-effects and adverse consequences (for example, lowering the priority of other vulnerable groups). Eventually, this might even contribute to fragmentation and represent a major challenge for multi-sectoral, systematic approaches.

Overall, the emerging picture suggests that MMPs describe overall aims and link these to recommended strategies, whereas project plans hold more detailed information about how the intentions of the PHA can be fulfilled. These findings might point towards the different purposes and periods of the included documents. Municipal plans describe long-term developments and ambitions, while project plans are more linked to specific challenges, target groups and time periods and represent hands-on working documents. This might be an important distinction in understanding what the plans describe and what knowledge is necessary for realising the purpose of the plan. Simultaneously, these findings illustrate the interdependency between municipal and project plans. On the one hand, municipal plans guide project aims for processes and outcomes. On the other hand, the ambition expressed in municipal plans is often realised through approaches and projects. Together, these approaches form the systematic processes that are workable to achieve social health equity, and thereby realise the overarching goal. A greater awareness of the use of the different purposes and contexts in which plans are applied might help to clarify how municipalities can plan for health equity in the long-term while developing and implementing short-term approaches targeting complex challenges, settings, or target groups.

Methodological Limitations

The insights described above are derived from a document analysis with the aim of obtaining a coherent picture of how central aims are followed up in local planning systems and structure local efforts. Inclusion (and exclusion) of documents thereby emerges as an important possible limitation. This also became visible in the context of this study: included documents were limited to overarching municipal plans (MPS; MMP; MAP) and project plans linked to participation in a specific project. This increased comparability across municipalities and enabled insights into the how existing plans correspond and guide the work of a specific project. However, including, for example, sector-specific plans or thematic plans developed only in specific municipalities might have yielded a more detailed picture about how intentions are followed up and how work with the specific project influenced subsequent working methods and planning documents to ensure a coherent development.

Content analysis does not move forward in a linear fashion, and there are no simple guidelines for data analysis: each inquiry is distinctive, and the results depend on the skills, insights, analytic abilities, and style of the investigator. The fact that there is no simple, ‘right’ way of doing it, and that we had to judge what variations were most appropriate for our problems, might be considered a limitation. In addition, we found that the inter-connected nature of these intentions yielded some obstacles in terms of the operationalization of search words. As such, search words used might be considered a limitation, as other search words might have provided other results. Using ‘systematic knowledge-based’ as search words, which is a quite a broad overall theme, might influence the frequency of use, and should, therefore, be treated with caution. However, complementary searches to search for other potential other themes relating to all three intentions of interest (systematic knowledge-based, cross-sectoral, health equity), as well as finding the context in which the words are used, might limit potential problems. Excessive interpretation on the part of the researchers might also be considered a risk to successful analysis. However, this applies to all qualitative methods of analysis.

Even so, content analysis is extremely well-suited to analysing the multifaceted phenomena of public health planning. An advantage of the method is that the large volume of textual data and different textual sources could be dealt with and used in corroborating the knowledge on how intentions of the PHA [4] in Norway are visible in municipal plans and project planning documents. A clear definition of how the themes were coded also makes it replicable, which, in turn, will help with interrater reliability. Municipalities were selected using previously described criteria, with a view of being representative for municipalities in Central Norway taking part in the Program for Public Health Work in municipalities. However, it should be considered that the municipal plan process, even though it is regulated by law, varies across the included municipalities in terms of working processes, extent and priorities. Thus, the findings should be handled cautiously when considering generalisability to other municipalities or areas in Norway.

5. Conclusions

The present study reveals consciousness in municipality plans and documents about public health work as a whole-of-government and a whole-of-municipality responsibility.

The findings indicate that municipalities acknowledge and ensure that determinants of health form the starting point for knowledge-based public health work. In line with the intentions of the PHA, systematic knowledge-based processes in planning and decision-making processes are described across municipalities. However, variations occurred in respect to how intentions were operationalized across type of document and across municipalities. Beneficial structures and working procedures towards health equity are identified in the context of Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities project applications and plans. However, opportunities for further improvement arise in respect to anchor these structures and systematic knowledge-based working procedures in the wider municipal context. Further, improvements might be made in respect to a more systematic use of the local knowledge base (OPH) to determine challenges, as well as to define local aims and procedures. More explicit operationalizations of how processes contribute to achieve desirable outcomes can increase efforts placed in applying systematic processes.

Finally, effort placed on across-administrative levels and sectors to promote health and equity is still needed. A more conscious application of the planning documents and establishing cross-sectoral procedures that ensure new knowledge is being fed back into the municipal plans and organization might improve municipalities’ ability for systematic multi-sectoral approaches.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, M.L., S.H., K.S.A., R.M., E.H., J.T.V., E.R.S., B.E.V.A. and M.S.; methodology, M.L., S.H., K.S.A., R.M., E.H. and J.T.V.; formal analyses, M.L. and S.H.; resources, M.L.; data curation, M.L., S.H. and E.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L., S.H., K.S.A., R.M., E.H., J.T.V., E.R.S., B.E.V.A. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.L., S.H., K.S.A., R.M., E.H., J.T.V., M.S., B.E.V.A. and E.R.S.; project administration, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Norges Forskningsråd (Research Council Norway) no. 302705.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and assessed by Norwegian Centre for Research Data no. 768337.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the municipalities taking part in Program for Public Health Work in municipalities (2017–2027) in Central Norway for supplying requested documents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ministry of Health and Care Services. The Norwegian Strategy to Reduce Social Inequalities in Health 2007; Report No. 20 (2006–2007) to the Storting; Ministry of Health and Care Services: Oslo, Norway, 2007; Available online: http://www.regjeringen.no (accessed on 19 November 2022).

- van der Wel, K.A.; Dahl, E.; Bergsli, H. The Norwegian policy to reduce health inequalities: Key challenges. Nord. Welf. Res. 2016, 1, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, E.; van der Wel, K.A. Nordic Health Inequalities: Patterns, trends and policies. In Health Inequalities: Critical Perspectives; Smith, K.E., Bambra, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Care Services. Norwegian Public Health Act; Ministry of Health and Care Services: Oslo, Norway, 2011; Available online: http://www.regjeringen.no (accessed on 19 November 2022).

- Ministry of Local Government and Modernization. Norwegian Planning and Building Act; Ministry of Local Government and Modernization: Oslo, Norway, 2008; Available online: http://www.regjeringen.no (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Ministry of Health and Care Services. The Coordination Reform—Proper Treatment—At the Right Place and Right Time; Report No. 47 (2008–2009) to the Storting; Ministry of Health and Care Services: Oslo, Norway, 2009; Available online: http://www.regjeringen.no (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Ministry of Health and Care Services. Folkehelsemeldingen—Mestring og Muligheter; Report no. 19 (2014–2015) to the Storting; Ministry of Health and Care Services: Oslo, Norway, 2015; Available online: http://www.regjeringen.no (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Ministry of Local Government and Modernization. The Local Government Act; Ministry of Local Government and Modernization: Oslo, Norway, 1992; Available online: http://www.regjeringen.no (accessed on 19 November 2022).

- Fosse, E.; Helgesen, M.K. Policies to Address the Social Determinants of Health in the Nordic Countries; Nordic Welfare Centre: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019; Available online: https://nordicwelfare.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Rapport_Policies_SocialDeterminants_final.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Dahl, E.; Bergsli, H.; van der Wel, K.A. Sosial Ulikhet i Helse. En Norsk Kunnskapsoversikt; Oslo and Akershus University College: Oslo, Norway, 2014; Available online: http://www.hioa.no/helseulikhet (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Fosse, E.; Helgesen, M.K. How can local governments level the social gradient in health among families with children? The case of Norway. Int. J. Child Youth Fam. Stud. 2015, 6, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, S.; Torp, S.; Helgesen, M.; Fosse, E. Promoting health by addressing living conditions in Norwegian municipalities. Health Promot. Int. 2016, 32, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosse, E.; Sherriff, N.; Helgesen, M. Leveling the Social Gradient in Health at the Local Level: Applying the Gradient Equity Lens to Norwegian Local Public Health Policy. Int. J. Health Serv. 2019, 49, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, E.; Elstad, J.I. Sosial Ulikhet Tar Liv; Rapport Nasjonalforeningen for Folkehelsen 9/2022; ETN Grafisk: Oslo, Norway, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Arntzen, A.; Bøe, T.; Dahl, E.; Drange, N.; Eikemo, T.A.; Elstad, I.; Fosse, E.; Krokstad, S.; Syse, A.; Sletten, M.A.; et al. 29 recommendations to combat social inequalities in health. The Norwegian Council on Social Inequalities in Health. Scand. J. Public Health 2019, 47, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldblatt, P.; Castedo, A.; Allen, J.; Lionello, L.; Bell, R.; Marmot, M.; von Heimburg, D.; Ness, O. Rapid Review of Inequalities in Health and Wellbeing in Norway Since 2014; Report 3/2023; Institute of Health Equity, UCL Educational Media: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Auditor General of Norway. Riksrevisjonens Undersøkelse av Offentlig Folkehelsearbeid; Dokument 3:11 (2014–2015); Fagbokforlaget: Bergen, Norway, 2015; Available online: http://www.riksrevisjonen.no (accessed on 1 July 2022)ISBN 978-82-8229-322-8.

- Program for Public Health Work in Municipalities. Available online: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/tema/folkehelsearbeid-i-kommunen/program-for-folkehelsearbeid-i-kommunene (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Program for Public Health Work in Trøndelag. Available online: https://www.trondelagfylke.no/programmet (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Lillefjell, M.; Magnus, E.; Knudtsen, M.S.; Wist, G.; Horghagen, S.; Espnes, G.A.; Maass, R.E.K.; Anthun, K.S. Governance for Public Health and Health Equity—The Tröndelag Model for Public Health Work. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 46 (Suppl. S22), 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillefjell, M.; Anthun, S.S.; Maass, R.E.K.; Innstrand, S.T.; Espnes, G.A. A Salutogenic, Participatory and Settings-Based Model of Research for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions: The Trøndelag Model for Public Health Work. In Global Handbook of Health Promotion Research; Innstrand, S.T., Potvin, L., Jourdan, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 13 May 2022; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lillefjell, M.; Maass, R.E.K. Involvement and Multi-Sectoral Collaboration: Applying Principles of Health Promotion during the Implementation of Local Policies and Measures—A Case Study. Societies 2022, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO The Helsinki statement on health in all policies. In Proceedings of the 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion, Helsinki, Finland, 10–14 June 2013. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506908 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). The Shanghai declaration on health promotion. In Proceedings of the 9th Global Conference on Health Promotion, Shanghai, China, 15–31 October 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-PND-17.8 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health. Available online: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/veiledere/systematisk-folkehelsearbeid (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Norwegian Planning and Building Act. 2008. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/planning-building-act/id570450/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Bowen, G.A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Norway. Sentralitetsindeksen. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/_attachment/413602?_ts=17085d29f50 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyngäs, H.; Kaakinen, P. Deductive Content Analysis. In The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research; Kyngäs, H., Mikkonen, K., Kääriäinen, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P.M.; Torney, D.; Ylä-Anttila, T. Governing a multilevel and cross-sectoral climate policy implementation network. Environ. Policy Gov. 2021, 31, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Stone, M.M. The design and implementation of cross-sector collaborations: Propositions from the literature. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C.; Stone, M.M. Designing and Implementing Cross-Sector Collaborations: Needed and Challenging. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).