Digital Habits of Users in the Post-Pandemic Context: A Study on the Transition of Mexican Internet and Media Users from the Monterrey Metropolitan Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

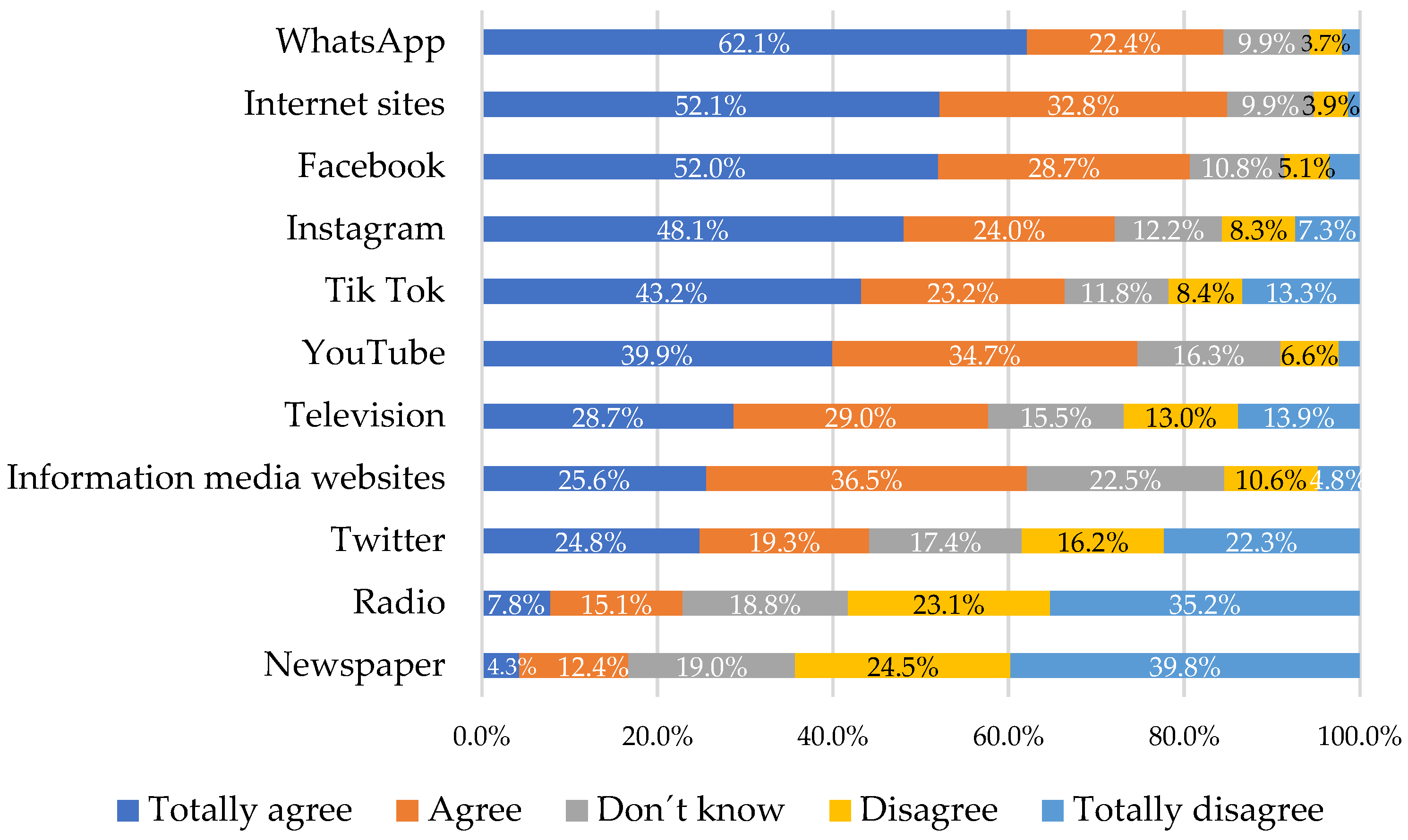

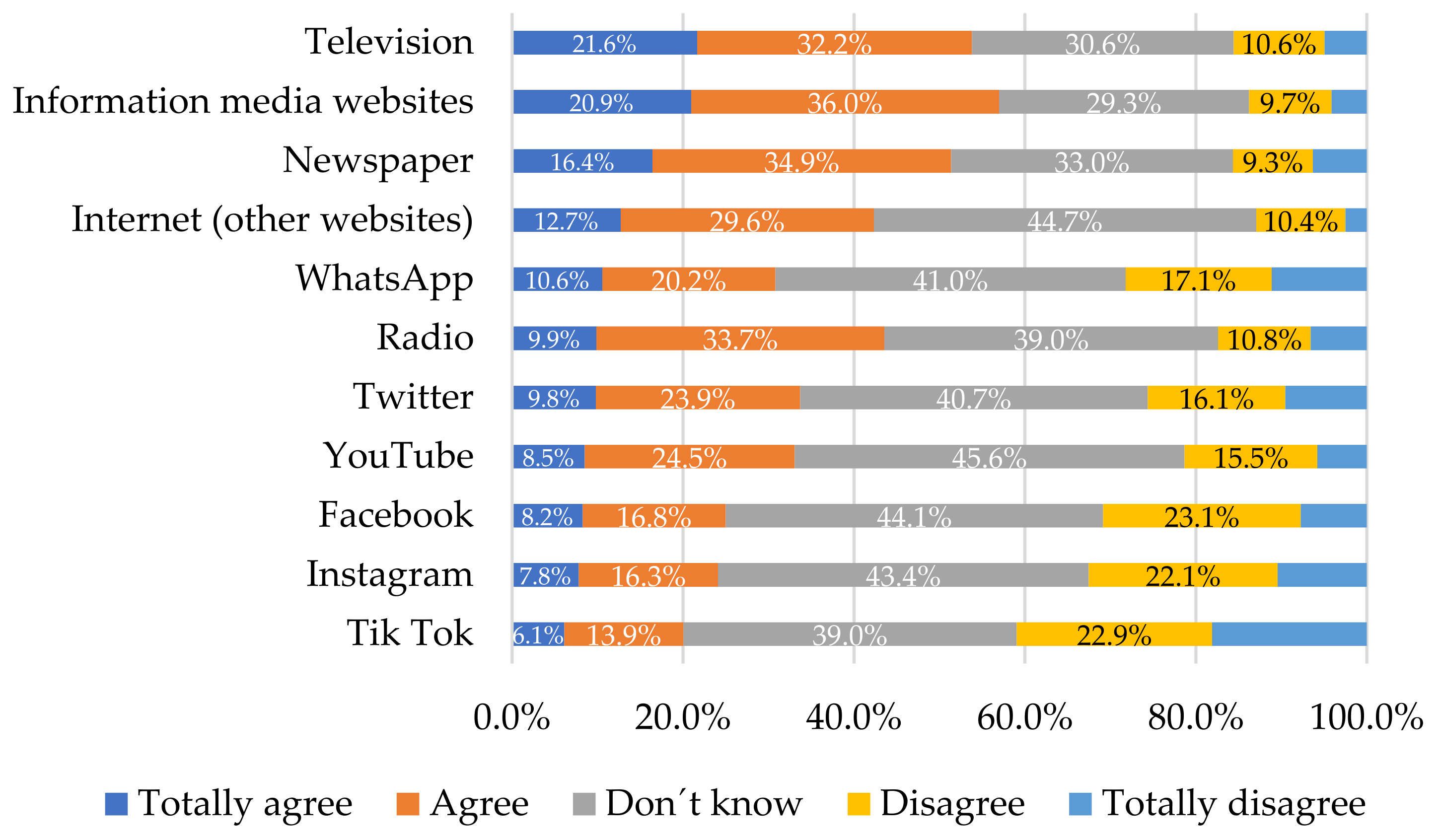

2. Trust and Digital Platforms

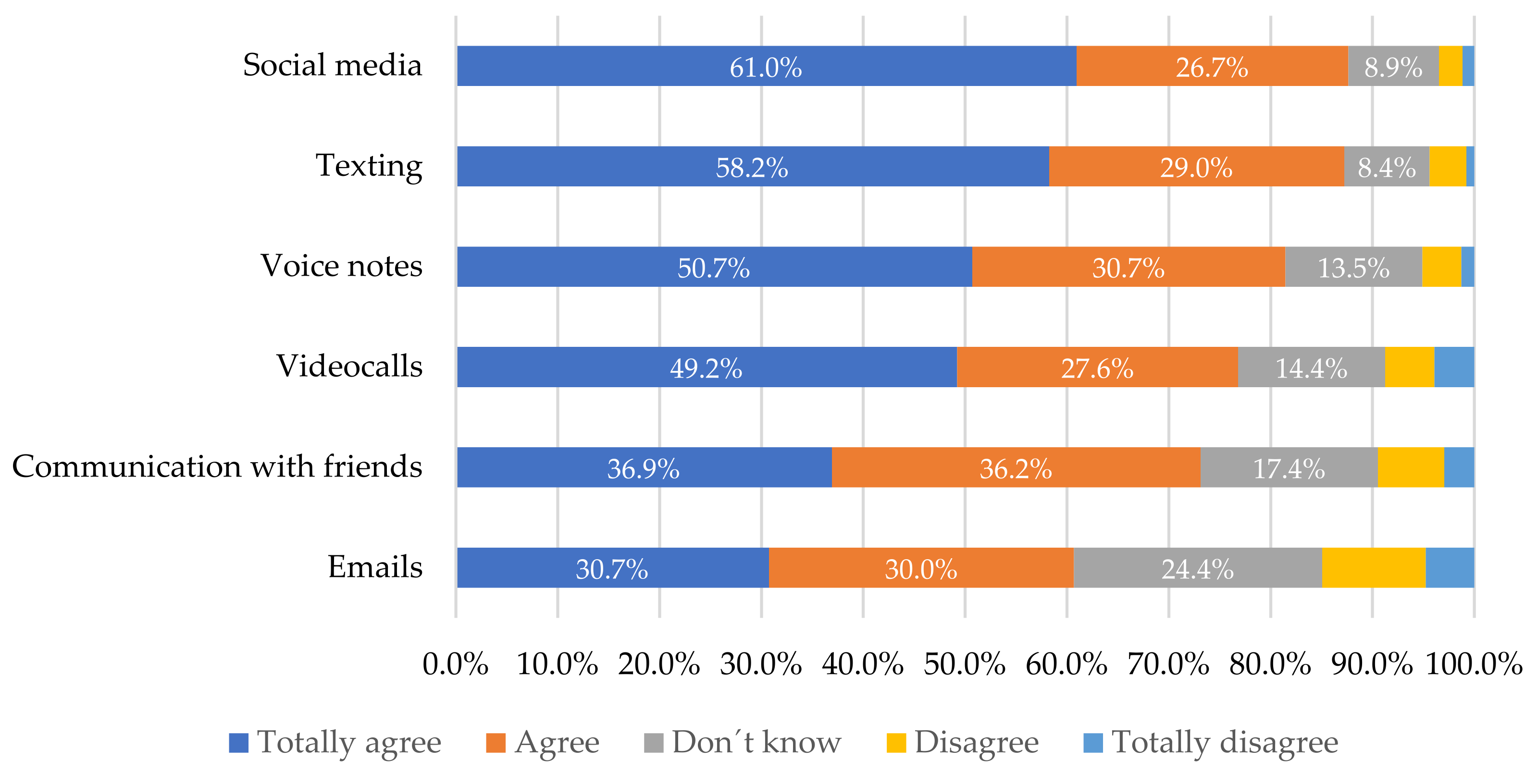

3. Consumption of Social Networks in the Era of COVID-19

4. Digital Entertainment Consumption

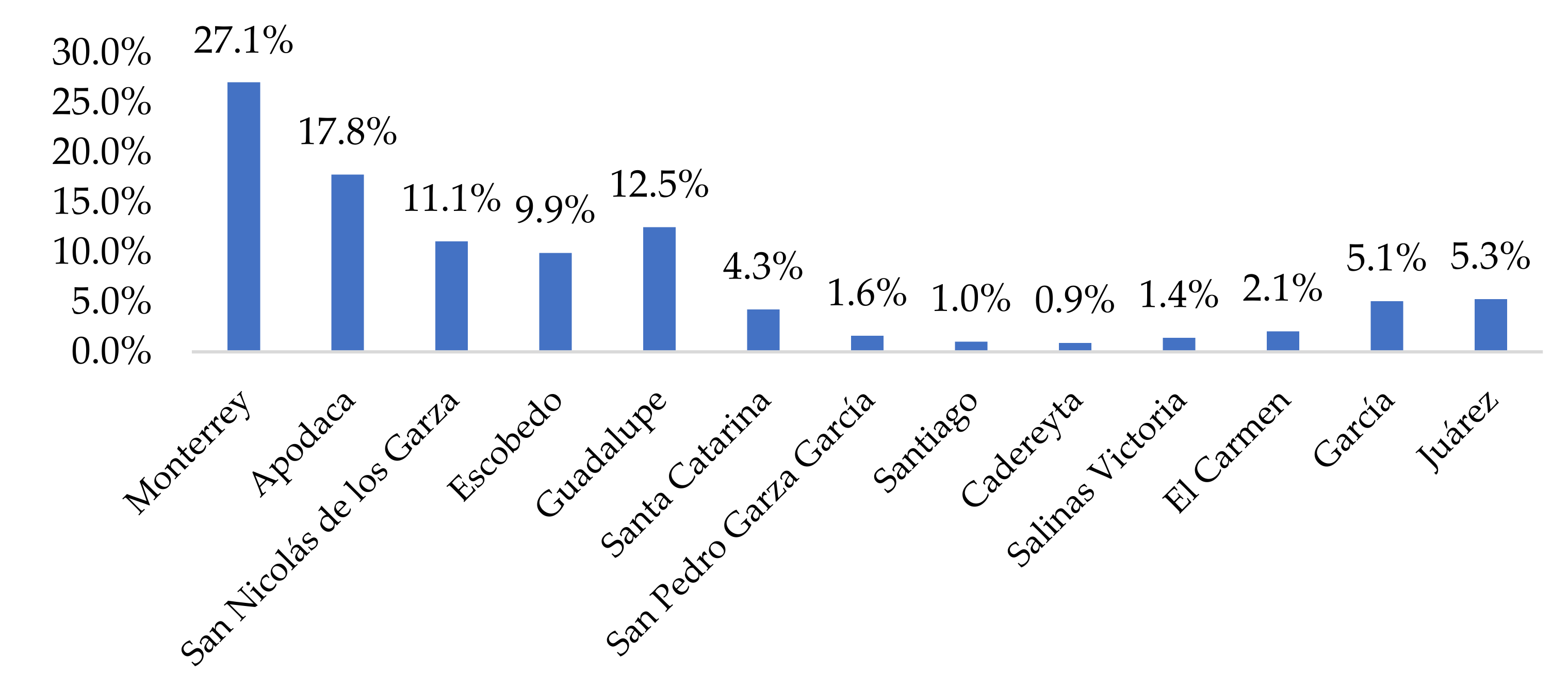

5. Methodology

Justification

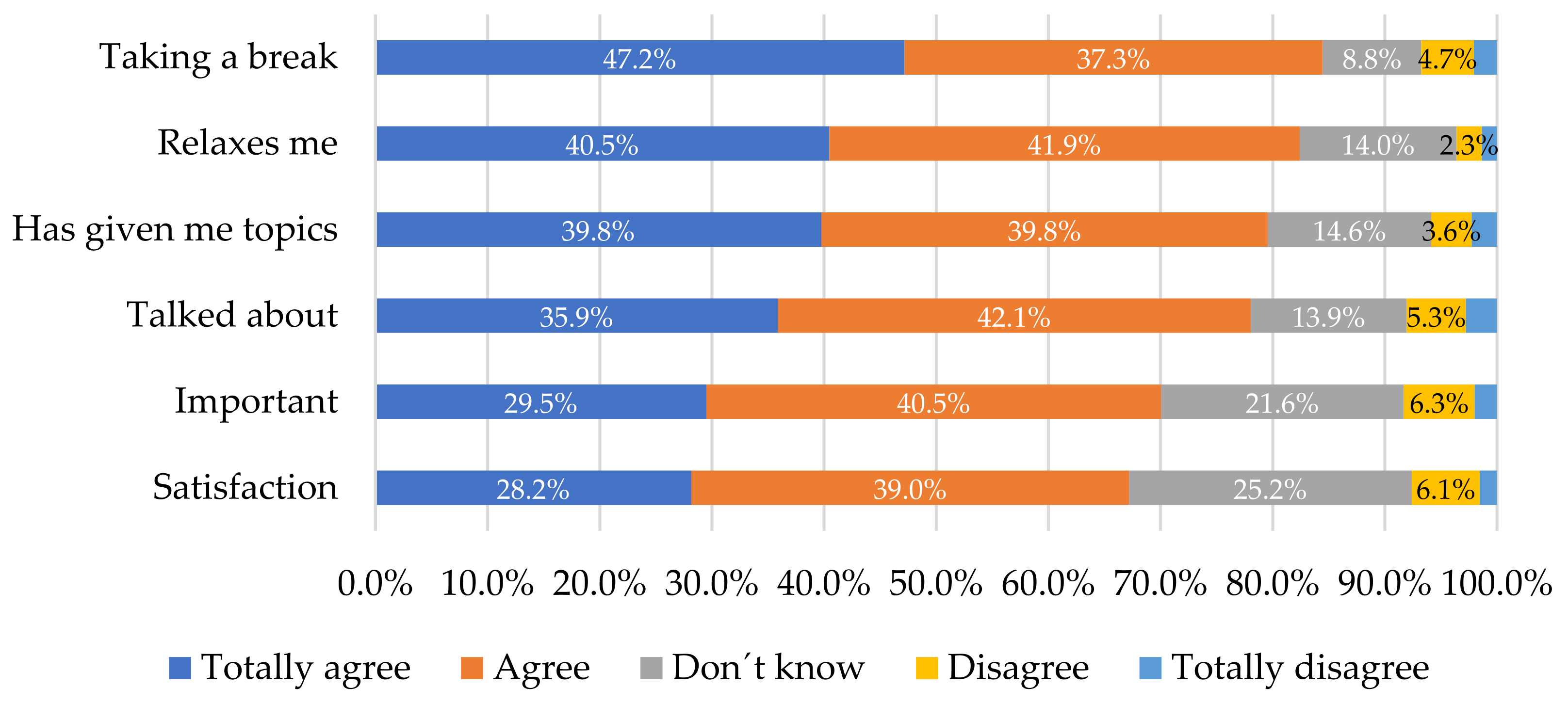

6. Results

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De la Garza, D.; Peña-Ramos, J. Transformaciones en la Vida Social a raíz del Aceleramiento de la Interacción Digital Durante la Coyuntura del Covid-19; Tirant lo Blanch: Mexico City, México, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gerding, T.; Syck, M.; Daniel, D.; Naylor, J.; Kotowski, S.E.; Gillespie, G.L.; Freeman, A.M.; Huston, T.R.; Davis, K.G. An assessment of ergonomic issues in the home offices of university employees sent home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Work 2021, 4, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Watterston, J. The changes we need: Education post COVID-19. J. Educ. Chang. 2021, 1, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Garza, D.; Barredo, D. Trust in Media and Technological Communication Tools During the COVID-19 Pandemic. A Study on Mexican Youth. In Communication and Applied Technologies; López-López, P.C., Barredo, D., Torres-Toukoumidis, Á., De-Santis, A., Avilés, Ó., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 447–457. [Google Scholar]

- Sherchan, W.; Nepal, S.; Paris, C. A survey of trust in social networks. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2013, 4, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, S.; Park, N.; Kee, K.F. Is there social capital in a social network site?: Facebook use and college students′ life satisfaction, trust, and participation. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2009, 4, 875–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, A. A Study on Influence of Trust, Social Identity, Perceived Risk and EWOM on Consumer Decision-Making Process in the Context of Social Network Sites. Master’s Thesis, Business Administration, MBA Programme, Blekinge Tekniska Högskola, Karlskrona, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hajli, N.; Sims, J.; Zadeh, A.H.; Richard, M.O. A social commerce investigation of the role of trust in a social networking site on purchase intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Frutos-Torres, B.; Pastor-Rodríguez, A.; Martín-García, N. Consumo de las plataformas sociales en internet y escepticismo a la publicidad. Prof. De La Inf. 2021, 30, e300204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amal Dabbous, A.; Aoun Baraka, K.; Merhej, S.M. Social Commerce Success: Antecedents of Purchase Intention and the Mediating Role of Trust. J. Internet Commer. 2020, 3, 262–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See-To, E.W.; Ho, K.K. Value co-creation and purchase intention in social network sites: The role of electronic Word-of-Mouth and trust–A theoretical analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I. The social media innovation challenge in the public sector. Inf. Polity 2012, 3–4, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limaye, R.J.; Sauer, M.; Ali, J.; Bernstein, J.; Wahl, B.; Barnhill, A.; Labrique, A. Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 6, e277–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijck, J.; Alinejad, D. Social media and trust in scientific expertise: Debating the Covid-19 pandemic in the Netherlands. Soc. Media+ Soc. 2020, 4, e2056305120981057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, S. COVID-19: How to be careful with trust and expertise on social media. BMJ 2020, 2020, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovari, A. Spreading (dis) trust: Covid-19 misinformation and government intervention in Italy. Media Commun. 2020, 2, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza Mohammadi, M.; Zarafshan, H.; Khayam Bashi, S.; Mohammadi, F.; Khaleghi, A. The Role of Public Trust and Media in the Psychological and Behavioral Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2020, 3, 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Ampon-Wireko, S.; Xu, X.; Quansah, P.E.; Larnyo, E. Media attention and Vaccine Hesitancy: Examining the mediating effects of Fear of COVID-19 and the moderating role of Trust in leadership. PLoS ONE 2021, 2, e0263610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayal, P.; Bharathi, S.V. Reliability and trust perception of users on social media posts related to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2021, 1–4, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melki, J.; Tamim, H.; Hadid, D.; Makki, M.; El Amine, J.; Hitti, E. Mitigating infodemics: The relationship between news exposure and trust and belief in COVID-19 fake news and social media spreading. PLoS ONE 2021, 6, e0252830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, I.; Lucas, N.; Henke, D.; Zigler, C.K. Association between public knowledge about COVID-19, trust in information sources, and adherence to social distancing: Cross-sectional survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 3, e22060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.H.C.; Liu, T.; Leung, D.K.Y.; Zhang, A.Y.; Au, W.S.H.; Kwok, W.W.; Shum, A.K.; Wong, G.H.Y.; Lum, T.Y.S. Consuming information related to COVID-19 on social media among older adults and its association with anxiety, social trust in information, and COVID-safe behaviors: Cross-sectional telephone survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 2, e26570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Galeazzi, A.; Valensise, C.M.; Brugnoli, E.; Schmidt, A.L.; Zola, P.; Zollo, F.; Scala, A. The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, S.F.; Chen, H.; Tisseverasinghe, T.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Butt, Z.A. What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: A scoping review. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e175–e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venegas-Vera, A.V.; Colbert, G.B.; Lerma, E.V. Positive and negative impact of social media in the COVID-19 era. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 4, 561–564. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, K.; Singh, S.K.; Chopra, M.; Kumar, S. Role of social media in the COVID-19 pandemic: A literature review. In Data Mining Approaches for Big Data and Sentiment Analysis in Social Media; Engineering Science Reference: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 91–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A.; Ho, S.; Olusanya, O.; Antonini, M.V.; Lyness, D. The use of social media and online communications in times of pandemic COVID-19. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2021, 3, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drouin, M.; McDaniel, B.T.; Pater, J.; Toscos, T. How parents and their children used social media and technology at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and associations with anxiety. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 11, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J. The relationship between burden caused by coronavirus (Covid-19), addictive social media use, sense of control and anxiety. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Zhou, G. COVID-19 stress and addictive social media use (SMU): Mediating role of active use and social media flow. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 635546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Galán, J.; Martínez-López, J.Á.; Lázaro-Pérez, C.; Sarasola Sánchez-Serrano, J.L. Social networks consumption and addiction in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Educational approach to responsible use. Sustainability 2020, 18, 7737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diepeveen, S.; Pinet, M. User perspectives on digital literacy as a response to misinformation. Dev. Policy Rev. 2022, 40, e12671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgman, A.; Merkley, E.; Loewen, P.J.; Owen, T.; Ruths, D.; Teichmann, L.; Zhilin, O. The causes and consequences of COVID-19 misperceptions: Understanding the role of news and social media. Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinform. Rev. 2020, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldkamp, J. The rise of TikTok: The Evolution of a social media platform during COVID-19. In Digital Responses to Covid-19; Hovestadt, C., Recker, J., Richter, J., Werder, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Olvera, C.; Stebbins, G.T.; Goetz, C.G.; Kompoliti, K. TikTok tics: A pandemic within a pandemic. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2021, 8, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendher, S.; Sharma, A.; Chhibber, P.; Hans, A. Impact of COVID-19 on digital entertainment industry. UGC Care J. 2021, 44, 148–161. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y. The Streaming War during the Covid-19 Pandemic; Arts Management & Technology Laboratory: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nhamo, G.; Dube, K.; Chikodzi, D. Implications of COVID-19 on gaming, leisure and entertainment industry. In Counting the Cost of COVID-19 on the Global Tourism Industry; Nhamo, G., Dube, K., Chikodzi, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 273–295. [Google Scholar]

- Aranyossy, M. Technology Adoption in the Digital Entertainment Industry during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Extended UTAUT2 Model for Online Theater Streaming. Informatics 2022, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindha, D.; Jayaseelan, R.; Kadeswaran, S. Covid-19 Lockdown, entertainment and paid ott video-streaming platforms: A qualitative study of audience preferences. Mass Commun. Int. J. Commun. Stud. 2020, 4, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Hollywood survival strategies in the post-COVID 19 era. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Singharia, K. Consumption of OTT media streaming in COVID-19 lockdown: Insights from PLS analysis. Vision 2021, 1, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryon, C. TV got better: Netflix’s original programming strategies and the on-demand television transition. Media Ind. J. 2015, 2, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, M.L.; Uribe Sandoval, A.C. Netflix original series, global audiences and discourses of streaming success. Crit. Stud. Telev. 2021, 2021, 17496020211037259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havard, C.T. Disney, Netflix, and Amazon oh my! An analysis of streaming brand competition and the impact on the future of consumer entertainment. Find. Sport Hosp. Entertain. Event Manag. 2021, 1, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, A. Streaming Giants Carve New Paths in India: The Rise of Female Production, Content, and Consumption. Stud. World Cine. 2022, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, O. Picturing Diversity: Netflix’s Inclusion Strategy and the Netflix Recommender Algorithm (NRA). Telev. New Media 2022, 2022, 15274764221102864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmar, A.; Raats, T.; Van Audenhove, L. Streaming difference (s): Netflix and the branding of diversity. Crit. Stud. Telev. 2022, 2022, 17496020221129516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M. The Impacts of Service Quality, Perceived Value, and Social Influences on Video Streaming Service Subscription. Int. J. Media Manag. 2022, 2, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavale, S.; Singh, R. Study of perception of college going young adults towards online streaming services. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Res. 2020, 10, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Gruber, J.; Fuchs, J.; Marler, W.; Hunsaker, A.; Hargittai, E. Changes in Digital Communication during the COVID-19 Global Pandemic: Implications for Digital Inequality and Future Research. Soc. Media+ Soc. 2020, 3, 2056305120948255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanov., F.; Mursalov., M.; Rosokhata, A. Consumer Behavior in Digital Era: Impact of COVID-19. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2021, 2, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Garza, D.; Barredo, D. Democracia digital en México: Un estudio sobre la participación de los jóvenes usuarios mexicanos durante las elecciones legislativas federales de 2015. Index Comun. 2017, 1, 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Arana Arrieta, E.; Mimenza Castillo, L.; Narbaiza Amillategi, B. Pandemia, consumo audiovisual y tendencias de futuro en comunicación. Rev. De Comun. Y Salud 2020, 2, 149–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides Almarza, C.; García-Béjar, L. ¿Por qué ven Netflix quienes ven Netflix?: Experiencias de engagement de jóvenes mexicanos frente a quien revolucionó el consumo audiovisual. Rev. De Comun. 2021, 1, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/boletines/2021/OtrTemEcon/ENDUTIH_2020.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2022).

| Use Time | Approximately How Many Hours a Day Do You Dedicate to the Different Contents of Social Networks? | Approximately How Many Hours a Day Do You Spend Browsing the Internet? |

|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 1.7 | 3.5 |

| Between 1 and 2 h | 28.5 | 48.3 |

| Between 3 and 4 h | 42.7 | 27.5 |

| More than 5 h | 27.1 | 20.7 |

| Paired Differences | T | GL | Significance (Bilateral) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Dev. Standard | Average Error | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | |||||

| Inferior | Superior | |||||||

| Television | −0.583 | 1.328 | 0.034 | −0.649 | −0.517 | −17.292 | 1551 | 0.000 |

| News media websites | −0.416 | 1.189 | 0.030 | −0.475 | −0.356 | −13.769 | 1551 | 0.000 |

| Internet | −0.275 | 1.012 | 0.026 | −0.326 | −0.225 | −10.713 | 1551 | 0.000 |

| Radio | −0.051 | 1.077 | 0.027 | −0.105 | 0.003 | −1.862 | 1551 | 0.063 |

| −0.082 | 0.976 | 0.025 | −0.130 | −0.033 | −3.302 | 1551 | 0.001 | |

| YouTube | −0.008 | 1.106 | 0.028 | −0.063 | 0.047 | −0.275 | 1551 | 0.783 |

| 0.115 | 1.078 | 0.027 | 0.062 | 0.169 | 4.215 | 1551 | 0.000 | |

| TikTok | 0.006 | 1.117 | 0.028 | −0.050 | 0.061 | 0.205 | 1551 | 0.838 |

| 0.205 | 1.149 | 0.029 | 0.148 | 0.262 | 7.027 | 1551 | 0.000 | |

| 0.032 | 1.077 | 0.027 | −0.022 | 0.085 | 1.155 | 1551 | 0.248 | |

| Use Time | Approximately How Many Hours a Day Do You Spend on Different Entertainment Content? |

|---|---|

| 0 h | 3.2 |

| Between 1 and 2 h | 47.2 |

| Between 3 and 4 h | 35.2 |

| More than 5 h | 14.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de la Garza Montemayor, D.J.; Ibáñez, D.B.; Brosig Rodríguez, M.E. Digital Habits of Users in the Post-Pandemic Context: A Study on the Transition of Mexican Internet and Media Users from the Monterrey Metropolitan Area. Societies 2023, 13, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13030072

de la Garza Montemayor DJ, Ibáñez DB, Brosig Rodríguez ME. Digital Habits of Users in the Post-Pandemic Context: A Study on the Transition of Mexican Internet and Media Users from the Monterrey Metropolitan Area. Societies. 2023; 13(3):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13030072

Chicago/Turabian Stylede la Garza Montemayor, Daniel Javier, Daniel Barredo Ibáñez, and Mayra Elizabeth Brosig Rodríguez. 2023. "Digital Habits of Users in the Post-Pandemic Context: A Study on the Transition of Mexican Internet and Media Users from the Monterrey Metropolitan Area" Societies 13, no. 3: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13030072

APA Stylede la Garza Montemayor, D. J., Ibáñez, D. B., & Brosig Rodríguez, M. E. (2023). Digital Habits of Users in the Post-Pandemic Context: A Study on the Transition of Mexican Internet and Media Users from the Monterrey Metropolitan Area. Societies, 13(3), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13030072