Abstract

This article is concerned with equalities nonprofit organizations’ activities to achieve substantive representation in policy-making through a sub-state government. It draws on three strands of the interest representation literature from equalities theory, nonprofit sector studies, and social movements theory. The analytical framework synthesizes these to provide a new approach for examining equalities nonprofit organizations’ policy influencing. Drawing on equalities theorists’ accounts of mainstreaming, and understandings of campaigns from social movement literature, it explores nonprofit organizations’ positioning in relation to government in order to advance equality. This analysis engages with questions raised by nonprofit scholars about nonprofit organizations’ independence from government and their capacity to retain a critical voice. An overarching institutionalist lens enables an examination of the formal and informal facets that shape policy influencing approaches. The research question is: How have equalities organizations engaged with the institution of a nonprofit-government partnership to promote substantive representation in policy? This research uses semi-structured elite interviews to explore key policy actors’ accounts. The case study is the statutory Welsh nonprofit sector–government partnership. Findings suggest the equalities nonprofit organizations involved in this partnership deploy a sophisticated array of action repertoires as part of an interrelated web of nuanced, multi-positioned influencing activities. This agility enables the sector to maintain some capacity to be critical of the state whilst sustaining informal relations with state policy actors.

1. Introduction

This article is concerned with the activities to achieve substantive representation in policy-making that are adopted by equalities organizations in their relationship with a sub-state government. The research question being addressed is: How have equalities organizations engaged with the institution of a nonprofit sector–government partnership to promote substantive representation? It is important to clarify what is meant by equalities organizations since this is not a universally recognized term. It refers to a particular set of nonprofit organizations that can represent the interests of different equalities groups. The use of the plural “equalities” is an established trend in equalities theory reflecting the multiple identity categories and different experiences of “diverse social groups” [1] (p. 2). For example, in the UK context, these categories are often understood to be age, disability, gender reassignment, “race”, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation because these categories are enshrined in legislation as the protected characteristics of the Equality Act (2010). Although it should be noted that there are legislative differences between the four UK nations that can shape understandings of equalities categories. For example, the Welsh Government has brought in the socioeconomic inequality as a duty under the Equality Act (2010). Beyond specific categories, intersectionality theory highlights the multitude of sub-categories that exist within and across identity categories [2,3]. Neither “equality” or “equalities” are ubiquitous terms. In North America, the composite term “diversity and inclusion” has increasing usage [4]. Although diversity has multifarious meanings and paradigms that overlap with representativeness and inclusion in complex and nuanced ways that are beyond the scope of this paper [4], where “diversity and inclusion” is concerned with multiple identities, particularly of underrepresented groups, it is comparable to this paper’s use of “equalities”. For the purposes of clarity, in this study, “equalities organizations” refers to the nonprofit organizations that represent the interests of constituents experiencing inequality due to age, disability, gender, gender identity, “race”, religion, sexual orientation, or socioeconomic factors and any intersections between and within these categories.

It is also helpful to examine the meaning of substantive representation. Pitkin [5] (p. 12) coined the term substantive representation, describing it as linking representation with “the substance of the activity” and an “acting for others”. Substantive representation can be understood as a “process” whereby equalities organizations act to promote equality [6] (p. 151). These organizations may act in multiple ways, but this paper applies this concept to understand how organizations that represent different equalities groups take action to impact on government policies. Saward [7] (pp. 4–5) distinguished his approach from Pitkin’s by focusing on “the representative claim”. Thus, he recognizes the distinction between the claim and claims-making. Here we aim to explore substantive representation by analyzing both equalities organizations’ claims and their claims-making when seeking to influence policy.

The research question was developed through a synthesis of relevant strands of the extant literature on how policy influence is pursued. Given that equalities organizations are nonprofit organizations, it is appropriate to draw on policy influencing accounts from the fields of equality literature and the nonprofit literature. The latter encompasses scholars who are concerned with the nonprofit sector (or not-for-profit), and this might variously be referred to as the voluntary sector, the third sector, or civil society organizations. (There are subtle differences both in these terms’ meanings and political signifiers which are context dependent, and these differences have been examined elsewhere [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], but for the purpose of this article, they can be regarded as belonging to one international field of study.) As shall be detailed, equalities theorists, and particularly feminist scholars, have developed understanding of how government policy-making can be shaped to advance equalities through mainstreaming strategies being adopted within government mechanisms [17,18,19]. In contrast, nonprofit sector scholars have particularly scrutinized the constraints on nonprofit organizations when they develop close relationships with governments [8,20]. A related but distinct third strand of literature that applies to these equalities organizations is that of social movements theory [21]. This paper draws on appropriate aspects of the social movements literature to interpret these organizations’ claims and claims-making. Of particular interest is how these literatures engage with insider–outsider positions [22,23]. Mainstreaming has often been concerned with introducing tools for advancing equalities in internal governance structures [17,18], and social movements have conventionally been conceptualized as exerting influence in more contested ways situated outside of the state [23], though there has been some blurring of these roles [22]. Nonprofit sector scholars have recognized that organizations may occupy insider positions in their relationship with government but have raised concerns about the consequences for maintaining independence [8,20,24]. Nonprofit sector studies have also reconceptualized insider–outsider theory to allow for organizations to occupy multiple positions [13,25] or venues [26,27,28]. This study draws on both mainstreaming and social movements literature alongside these understandings from nonprofit sector studies to consider the positioning of equalities organizations across the insider–outsider spectrum. Thus, a case is made for examining how substantive representation is related to nonprofit organizational positioning with the government and strategic institutional alignment in terms of insiders and outsiders. New institutionalism is concerned with both the formal and informal facets of an institution, focusing on how an institution interacts with its members’ behavior [29,30,31,32,33]. Therefore, a new institutionalist lens enables a consideration of both the formal and informal policy-influencing tools that are used by such interest groups. Since new institutionalism also encourages us to consider how an institution shapes it members, this is compared with nonprofit scholars’ exposition of organizational independence to contribute to our understanding of how equalities organizations activities are shaped by their interactions with government. (Further explanation of these literatures and justification for bringing these strands together is given in the analytical framework detailed in Section 2). The significance of this approach is that it synthesizes key elements of different bodies of knowledge to provide new insights into how equalities nonprofit organizations act to influence policy.

The context of interest to this study is where a government has introduced a governance mechanism through which it enables the nonprofit sector to influence policy. Governance refers to the sharing of responsibility for governing [34] between multiple levels of government and between different sectors, both in the provision of public services and in policy-making [35]. However, it is specifically the involvement of the nonprofit sector in policy-making that is of interest to this paper. The extent that nonprofit organizations are given the opportunity to collaborate with governments varies across the globe [36]. Therefore, the case study selected for this research is of particular interest because it is a formal sub-state nonprofit-government partnership that has been written into legislation within Wales, in the United Kingdom. An underexplored area is to consider how a formal governance mechanism intended to allow these interest groups to shape government policy-making shapes the policy influencing activities of such interest groups. The research question synthesizes these theoretical threads together in the context of this partnership. Semi-structured elite interviews were conducted with policy actors engaged in this case study partnership and discourse analysis was used to interpret these data.

This paper first sets out the analytical framework that underpins this study beginning with making the case for why equalities organizations are a particular genre of nonprofit organizations worthy of study in the context of state policy. It then progresses by examining how the different bodies of literature can be utilized to extend our understanding of how such organizations position themselves in relation to government and governance mechanisms. The case is then made for why this analysis benefits from an institutionalist lens. Details of the case study partnership are provided followed by an overview of the research methods applied in this study. The results are presented, starting with examining policy actors’ accounts of formal policy-influencing in the partnership as a means of promoting substantive representation against the context of mainstreaming theory. It then addresses the nature of informal claims-making of the equalities nonprofit sector. It considers what this tells us about their insider–outsider positioning and the implications in terms of the sector’s ability to take a critical role and hold government to account. Finally, it considers whether collaboration with government might shape the policy influencing activities of these organizations. The subsequent discussion reveals how some aspects of equalities organizations’ formal policy-influencing accord with, but also differ from, that seen in mainstreaming accounts. Furthermore, it will consider the significance of the extensive use of informal tools in conjunction with formal ones to achieve policy influence both within and beyond the Partnership. A third key finding discussed is how nonprofit organizations can offer a critical voice, whilst maintaining close informal relations with government.

2. Analytical Framework

2.1. Equalities Organizations Are a Distinct Form of Interest Group

This study is concerned with a particular set of organizations which are those that seek to represent equalities interest groups in policy-making. Scholarship of interest groups does not tend to recognize equalities interests as a distinct grouping but does recognize certain subpopulations of interest groups such as nonprofit organizations or social movements organizations [37]. Of these, nonprofit scholars have not tended to exclusively consider equalities organizations. Instead, attention has been given to the well documented diversity deficit that exists in the wider nonprofit sector, which highlights the sector’s failings in representation in boards and staff [4,38]. Thus, equalities nonprofit organizations are less well understood, with just a few important exceptions amongst nonprofit sector scholars [39,40].

Turning attention to social movements literature, according to Diani and Della Porta [21] (p. 20), social movements are defined as consisting of actors with a distinct collective identity engaging in collective action of a conflictual nature and linked by dense informal networks. They include the environmental movements, peace movement, solidarity movement, women’s movement, and movements concerned with the rights of discriminated minorities [41,42], although old social movements were traditionally associated with class cleavages, unions, and the labor movements [42]. Clearly, social movements encompass many equalities movements (albeit not all equalities organizations) but also many non-equalities movements. Social movements are conventionally conceptualized as associated with informal networks [21], whilst this study is concerned with formal organizations. As noted in the introduction, literature on social movements usually conceives of them as extra-institutional, thus situated outside of the state [21,23]. Therefore, social movements are not usually understood to operate within government partnership structures. However, there is growing recognition that some social movements are also developing sophisticated insider strategies [22]. Thus, social movements literature intersects with equalities organizations but is distinct.

It is illuminating to consider how the organizations that represent equalities interests align themselves with these terms. This is shaped by context. In the UK, they might collectively identify as “equality organizations”, which is more commonly used in practice than its plural counterpart (equalities organizations). However, they tend to describe the interests that they represent to be those groups associated with the particular social movement with which they are aligned, such as women’s movement, disability movement, “race” equality movement, et cetera [43]. Moreover, in governance settings, this notion of the equalities constituencies that they represent can compete with a second understanding of interest representation, which is to represent nonprofit sector organizational interests, although these competing understandings of representation are seldom acknowledged by policy practitioners [43]. Thus, these organizations do not separate out these fields in the same way that theorists aligned with social movements, equality theory, or nonprofit sector studies have a tendency to do. Therefore, this is a further justification for examining where these literatures intersect.

This study makes the case for a greater equalities focus in the interest group literature concerned with governance, and does so with recognition that such interests are represented by nonprofit organizations which are associated with particular social movements that correspond to these equalities interests. This paper seeks to contribute towards addressing this gap in interest group literature. In order to do this, some consideration must be given to the position of such organizations within a governance mechanism.

2.2. Positioning and Influence

Governance settings that bring together governments and nonprofit organizations raise questions about the positioning of the nonprofit sector. Positioning refers to the decisions organizations make to position themselves to be heard in society [44]. It can be applied to nonprofit sector organizations to understand their strategic decisions in how they position themselves [45]. Insider–outsider theory is the classic exposition of this and has been used widely in social and political science. For example, Grant [46,47] uses it to look at how interest groups seek to influence political decision-making. Insider groups are consulted regularly by government, but outsider groups either “do not wish to” be in such close relationships with government or are “unable to gain recognition” [46] (p. 19). Several interest group theorists have identified a number of divisions on the insider–outsider continuum to create typologies [13,48,49,50]. For example, Malony et al. [48] distinguished between the outsiders that chose to ideologically position themselves outside to maintain critical or adversarial positions and those who want to be included but lack the means. In certain parts of the world, even trying to promote the interests of identity groups can put equalities organizations in conflict with governments which can threaten their existence [51,52], though which equalities groups are vilified by government discourses does vary across the globe [53]. There are also parts of the world where it is very unusual to conceive of having nonprofit sector organizations cooperating with governments in an insider role [36]. When these different positions are available to interest groups, both insider and outsider approaches are recognized for their ability to impact on government policy in different ways [54]. Notably, where insiders influence public officials through formal channels, outsiders use tactics such as mobilizing grassroots activism [22,55]. It is the latter which are usually conceptualized as social movement activities [21,23].

As noted above, Saward [7] builds on Pitkin’s notion of actions in substantive representation by distinguishing between the representative claim and the claims-making activities. A similar distinction is made within social movements literature by Tilly [56] who identified “campaigns”, which he described as “sustained, organized and collective claims”, and “repertoires”, by which he referred to the deployment of a range of political influencing actions [56] (p. 308). “Repertoire” is a useful term because it recognizes the “performance” and conjures up a “stock” of activities from which the key actors select [57] (p. 2). However, the action repertoires of social movements are set apart because they are usually understood to be conflictual in nature and protests are conventionally viewed as their principle activity [21]. Thus, the activities of social movements might include “processions; vigils; rallies; demonstrations; [and] petition drives” [56] (p. 308). In contrast, within the civil society literature, formal governance structures are often seen to place nonprofit sector organizations in an insider position [39]. Yet even where government–nonprofit sector partnerships exist, this does not give all nonprofit organizations an inside role. Nonprofit scholars, particularly in the UK, have noted that where larger organizations are positioned well, are politically articulate, and have the resources to participate in governance, smaller ones are disadvantaged by not having the resources or capacity to engage and remain ignorant of the engagement structures available [39,55,58,59,60,61,62]. For example, Royles (2007) described the tendency for a two-tier civil society to develop in Wales, which has an elite inner circle alongside an excluded outer collection of civil society organizations. Whilst the danger of certain nonprofits being excluded has been substantially explored, gaps remain in the existing literature in terms of those organizations that do participate in understanding the effect on nonprofit sector claims-making of governments’ attempts to create an “Inside Access Model” where selected groups have “easy and frequent access to political decision makers” [63] (p. 135).

Whether interest groups should adopt a conflictual or collaborative approach is strongly debated within nonprofit sector studies. Existing works highlight concerns that the state’s management of the nonprofit sector can threaten the sector’s autonomy and distinctive voice [8,12,14,20,24,25,34,64]. For example, Carmel and Harlock [8] warned that close collaborative relationships with governments would render the nonprofit sector ‘a governable terrain’. Yet, it has also been recognized that the nonprofit sector’s position on the dimensions of conflict or collaboration and political or social spheres is continually being reshaped by “the discourses of institutional actors” [65,66] (p. 16).

Related to this concern around autonomy is whether the sector is able to sustain its critical voice when it has a close collaborative relationship between the nonprofit sector and government. Certain governance models are premised on nonprofit organizations providing critical oversight of the elected representatives [67]. This stems rights back to De Tocqueville’s interpretation of civil society holding the state to account which he considered to be an essential protection against state despotism [15,68]. A particular form of this critical nonprofit sector role has developed in response to public dissatisfaction with state welfare provision and been aided by development of new forms of communication between citizens and the administrative system [69]. The use of governance structures to provide a service-user voice can be traced back to Beresford and Croft [70] and earlier. The scrutiny of the third sector’s critical voice is often examined under the rubric of welfare pluralism; when the nonprofit sector is contracted to deliver services on behalf of the state, this can compromise its independence [12,15,24,34,36,58,62,71,72]. In turn, it may stunt its advocacy role [36,55,64]. This is exacerbated by the impact of austerity where nonprofit sector organizations’ funding dependencies on the state leads to “self-muzzling” and “self-censorship” with muted criticism of government [25] (p. 42) [14] (p. 8) [66]. A gap in knowledge is the extent to which this restriction might occur in other settings, such as a policy-making partnership.

Some insider–outsider typologies are concerned with conflict and collaboration, such as Maloney et al. [48] (described above); others are more concerned with the degree that organizations are contracted to deliver government funded programs, such as Buckingham, who distinguishes between comfortable, compliant, and cautious contractors as insiders or non-contractors as outsiders [13]. Some typologies synthesize these dimensions, such as Young [49], who distinguishes between organizations that are complimentary (delivering state funded programs), supplementary (provides services additional to the state), and adversarial (aiming to influence policies). These typologies are valuable in revealing the complexity and entanglement of different dimensions of insider–outsider, contractor–noncontractor and antagonist–collaborator relationships in institutional settings. They also reveal the gap in understanding interest groups that are engaged in collaboration with governments for the purpose of policy-making.

However, here some insights on insider strategies for pursuing policy change can be gleaned from equalities literature, particularly with respect to mainstreaming theory. Definitions of mainstreaming vary [18,73,74]. Gender mainstreaming can generally be understood as a “systematic incorporation of gender issues” throughout government and other institutions [75]. This has been broadened to equality mainstreaming [73,76,77]. Rees [18] (p. 560) defines mainstreaming as promoting equality through “systematic integration into all systems and structures, into all policies, processes and procedures”. Thus, mainstreaming systematically incorporates diverse equalities perspectives into all levels and all stages [78,79]. Consequently, where equalities claims are found across the policy-making processes, this can reflect a mainstreaming strategy.

As well as extending our knowledge of equalities claims, mainstreaming theory can further understanding of claims-making activities. For example, whilst a full discussion of the literature on mainstreaming is beyond our scope, it is worth noting that mainstreaming literature details the tools prescribed for influencing policy [17,18,19]. In brief, these include monitoring, evaluating, and auditing; use of disaggregated data and equality indicators; equalities budgeting; and impact assessments [17,18,19]. Another mainstreaming tool is “visioning” which involves recognizing how “rules and practices need to be changed” to promote equality [18] (pp. 568–569). An underexplored area is to relate these tools to the action repertoires utilized by equalities organizations’ engagement inside formal governance structures. Succinctly, whilst nonprofit sector studies offer some accounts of insider roles of these interest groups but has hitherto tended to neglect their engagement in formal governance mechanisms for the purpose of policy-making, mainstreaming theory can contribute towards this gap in elucidating how equalities claims can be advanced in these setting through mainstreaming tools.

There has been some recognition amongst nonprofit sector theorists that a limitation of insider–outsider accounts is the assumption that organizations occupy just one position [13]. Hemmings [25] proposed that nonprofit organizations occupy a range of insider–outsider positions. Relatedly, “venue shopping” describes multiple venues being used to influence policy [26], whereby organizations strategically switch institutional venues to achieve policy influence [27,28]. An underexplored area of research is to consider how equalities organizations’ involvement in a formal nonprofit sector–government partnership relates to their institutional positioning with respect to these multiple venues in governance and the implications for equalities being advanced.

2.3. An Institutionalist Lens on Equalities Nonprofits Policy Influencing Activities

Research into substantive representation by the nonprofit sector has been relatively underexplored as a political space [80]. A justification for doing this through an institutional lens is given by Schmidt [81] (p. 305), who maintains that discursive institutionalism allows an analysis of “the power of persuasion” and “the construction and reconstruction of interests” in the political sphere. In order to do this, we need to be clear which institutionalism is being utilized. Here, we are referring to new institutionalism, which is concerned with how institutions interact with members’ behavior and focuses on both informal conventions and formal structures (Lowndes 2008:156) rather than old institutionalism, which compares whole systems of government, and focuses on how internal organizational processes evolve and affect organizational behavior (Lowndes 2008; Peters 2012). This new institutionalist lens on the formal and informal facets of the institution is helpful for this study in scrutinizing both the formal claims and claims-making activities that take place through the formal structures of a governance institution as well as the informal activities that also take place within and around such an institution to achieve policy influence.

There are a number of forms of new institutionalism, and whether these different forms can be amalgamated is contested [33,82,83,84]. Certain institutionalists maintain such an amalgamation can take place, notably those belonging to the fields of discursive institutionalism and feminist institutionalism [32,81,85]. However, without rehearsing these arguments, the forms of institutionalism that are of particular interest to this paper are discursive institutionalism and sociological (also called normative) institutionalism. Discursive institutionalism gives primacy to discourses and ideas which must be understood in their contextual usage [81] (p. 304). Since discursive institutionalists understand discourse as a medium of power and understand institutional change to be achieved through discourses, there is a particular alignment here with understanding how equalities claims can be framed in informal institutional discourses [86]. This is in keeping with this study’s constructionist starting point.

Additionally, sociological (or normative) institutionalism introduces the idea of rules of appropriateness in which the actions and qualities deemed appropriate in institutional contexts are transmitted through socialization [29]. Sociological institutionalists are also constructionists [81]. Thus, informal norms prescribe and proscribe certain behaviors under the logic of appropriateness [29,87]. Understanding how a governance structure might convey a logic of appropriateness that shapes how nonprofits engage in policy-making accords with the aims of this research. This institutionalist perspective on how an institution constrains its members’ behavior is useful for the purpose of this study. It can lead us to examine informal norms which might be imposed on equalities organizations by a governance institution that shapes their policy influencing activities. This bring us back to the concern raised by nonprofit scholars about the extent that such organizations are able to maintain their independence and critical voice. It also raises the question of whether there are other constraints on the sector beyond this.

Having laid out this study’s analytical framework, the details of the case study partnership that has been selected for this research are now presented.

3. The Case Study Partnership

Our case study is the formal, statutory partnership between Welsh Government and the nonprofit sector, which is set out in legislation, specifically, the Government of Wales Act (GOWA) (1998 s114; superseded by GOWA 2006 s74) [88]. It requires the Welsh Government to uphold the interests of the sector and publish a Third Sector Scheme which will outline how the government will consult and assist the sector. As laid out in successive Third Sector Schemes [89,90], the principal structures of this Partnership are the Third Sector Partnership Council (TSPC) and a series of Ministerial Meetings. Jointly, these form a key nexus between ministers and representatives from twenty-five Welsh nonprofit thematic networks. Wales Council for Voluntary Action (WCVA) is the nonprofit sector infrastructure organization that coordinates this partnership [59]. The nonprofit sector–government partnership studied here does not have one overarching name that encompasses all its components; for ease of reference, it is henceforth referred to as “the Partnership”. This term refers collectively to the TSPC, the Ministerial Meetings, and the twenty-five thematic nonprofit networks.

The Welsh statutory partnership was established in 1998. It is an innovation associated with devolution in Wales. This notwithstanding, a partnership approach was part of a wider UK strategy of New Labour and the political discourses of Blair’s Third Way [35,59]. This is reflected in the use of the term “third sector” within the legislation that underpins the partnership and the policy actors’ discourses concerning the partnership. The UK’s Third Way rhetoric was also mirrored by international theorizing about nonprofit sector–government relations [20,36]. Thus, the Welsh partnership should be contextualized against this policy rhetoric of New Labour’s UK Government and the wider global picture of evolving state–nonprofit sector relations. It must also be related to the context of UK devolution and spatial rescaling, which is considered next.

Devolution in Wales was triggered by a referendum in 1997 [91] and was part of a wider shift towards devolution seen in the UK [35]. Blair had presented devolution as one facet of his Third Way [92]. This is in evidence with the creation of the National Assembly of Wales, the Scottish Parliament, and the Northern Ireland Assembly, alongside other steps towards devolution in England [93]. Beyond the UK picture, devolution forms part of a broader process of spatial rescaling of governance that occurred across Europe [94]. It has been described as a “scalar turn” whereby the national scale of governance is challenged by local and regional scales [93]. Therefore, Welsh devolution should be understood in the context of these wider UK and international governance changes.

The present Welsh case study has some features which render it a “revelatory case” [95]. The singular nature of this Partnership is its legal grounding. It put the voluntary sector at the center of Welsh politics [59]. This was noted in the National Assembly when the First Voluntary Scheme was adopted:

There is no similar requirement in England, Scotland, or Northern Ireland… There is no such statutory scheme anywhere else in Europe.[96]

Embedding state–nonprofit sector relations in legislation in this way is a unique governance feature [59,97], making Welsh devolution a key locus to explore contemporary nonprofit sector–government relations.

It is also appropriate to examine how equalities organizations are engaged within the Partnership because Welsh Government made a commitment to promote equality of opportunity in the exercise of devolved functions, including policy-making, under the same successive devolution statutes (Government of Wales Act 1998 s.120; 2006 s.77) [98]. This equalities clause is evidence that devolution provided a critical juncture for the advancement of equalities in Welsh policy-making [98,99]. The sub-state level of this case study is also of interest because devolution provides an opportunity for sub-state analysis of the position of equalities groups in policy-making [74]. Given these pioneering developments, it is appropriate to examine how such a Partnership is being used to advance equalities.

4. Materials and Methods

This qualitative research is underpinned by a constructionist position. Constructionism recognizes that various and multiple meanings develop as a result of social interactions [100] and that social phenomena are in a constant state of construction and reconstruction through continual interaction of social actors [101]. These foundations are appropriate for the present research since it seeks to understand the case study Partnership from participants’ perspectives. As noted above, constructionism provides the epistemological foundation for discursive institutionalism and sociological institutionalism, which jointly comprise the overarching theoretical lens upon which this study draws. Discursive institutionalism sets this understanding of meaning through discourse in an institutional context [81]. Moreover, discursive institutionalists in the sociological institutionalist tradition recognize that the norms which shape behavior are constructed through institutional discourses [81].

Semi-structured elite interviews were utilized for data collection in this study. Ethical approval was requested and secured from the Ethics Committee of Cardiff University’s School of Social Sciences prior to undertaking the research. A purposive sample of policy actors from Welsh Government, WCVA, and equalities nonprofit organizations were selected. Smith [102] has described the criteria through which an interviewee is identified as “elite”, which include the seniority of position in authority but it can also refer to people who influence important decisions, control resources, or have political authority [102]. The selection criteria for interviewees from Welsh Government and WCVA was on the grounds that these individuals had political authority and could influence important decisions and control resources with respect to the Partnership. The intended sample included officials from Welsh Government and WCVA who had direct responsibility for the TSPC or the Ministerial Meetings. Realistic expectations were given to the recruitment of ministers given that this is always constrained by the political implications for politicians [103]. The criterion for elites from the equalities nonprofit sector was those in senior positions in authority (i.e., chief executive, director, senior manager, or policy officer). Interviewees were drawn from organizations within the twenty-five thematic networks that were concerned with equalities.

Overall, the interviewees included 19 from equalities nonprofit sector organizations, 8 from WCVA, 13 from Welsh Government, which included 1 minister, and 1 from the Welsh Parliament, Senedd Cymru. In order to protect the anonymity of individual interviewees, it is important not to detail which equalities organizations the participants were recruited from nor which Ministerial Meetings the officials managed, given the small pool of potential elite interviewees.

The interviews were transcribed. The analytical framework informed the analysis, including the initial coding frame that was used and developed iteratively with the aid of NVivo software. The interview data were analyzed using critical discourse analysis (CDA) which again reflects the discursive institutionalist underpinnings of this study. There are a variety of approaches to CDA [104]. This study follows problem-orientated CDA described by Wodak [105], rather than the prescribed analytical steps developed by linguistic scholars, such as Fairclough [106]. In problem-orientated CDA, the specific research questions are used to identify how these discursive devices and rhetorical and interactional strategies are relevant to the research questions [107]. Thus, the discourse analysis was concerned with policy actors’ accounts of the claims and claims-making activities of the equalities nonprofit sector.

5. Results

5.1. Substantive Representation in the Formal Partnership

5.1.1. Equalities Organizations’ Claims through a Mainstreaming Lens

Welsh Government and WCVA accounts of the nonprofit sector’s equalities claims in the Partnership frequently described how they sought to advance equalities across a breadth of policy areas. It is typified by this official’s account:

The agenda is quite generic. It has to be… But they will provide a perspective on any agenda item that is colored by their particular area that they are representing… Whatever is being discussed more generically, they will say, ‘and then there’s… a racial equality aspect to this… doing the same thing for different equality areas.(Participant 1, Welsh Government)

This epitomizes how the equalities nonprofit sector is seen to bring equalities matters to all policy areas. Interviewees from equalities organizations supported this and gave specific examples of it occurring. For example, this disability organization sought to influence the contents of the Social Services and Well-being (Wales) Act 2014:

Our particular interests were around advocacy, direct payments and charging and then also … what we were lobbying for was for the UNCRPD [United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities] to be on the face of the bill.(Participant 31, Equalities Organization)

Evidently, the Act itself was not specifically a piece of equalities legislation, but this excerpt reveals how the disability sector sought to influence it to benefit disabled people.

Where equalities claims are made in the context of policies that are not exclusively concerned with equalities matters, equalities theorists often make the criticism of “rhetorical entrapment”. This argues that such an approach is less transformative in its promotion of equality because the equalities issues are subsumed by other agendas [18,75,78]. Yet, such a criticism would only apply if this was the only way equalities claims were made. In the present research, interviews showed that nonprofit equalities claims were not limited to the adding of an equalities lens to non-equalities policy. Rather, interviewees also described claims made by equalities organizations that sought to influence equalities policy directly. Furthermore, analysis of these institutional discourses showed that these claims could be targeted at multiple stages in the policy-making process. One example of this was the instigation of new legislation, such as the Violence against Women, Domestic Abuse and Sexual Violence (Wales) Act (2015), which was attributed to “a strong women’s campaign” (Participant 25, Welsh Government). Claims could also target legislative guidance. An example of this are the claims for “LGBT inclusive sex and relationships education” (Participant 29, Equalities Organization), which interviewees felt led to the Welsh Government’s new “Relationships and Sexuality Education in Schools Guidance” [108]. Other accounts alluded to how equalities representatives influenced strategic policy implementation documents. For example, the Welsh Government’s “Tackling Hate Crimes and Incidents: Framework for Action” [109] was linked to hate crime campaigns from equality organizations associated with “race”, religion, disability, and older people (Participant 30 & 31, Equalities Organization). Furthermore, there were accounts of equalities organizations seeking to shape policy implementation directly. For example, the sector sought to influence the nature of health service provision for the trans community:

We were lobbying for a gender identity clinic in Wales. We’ve changed the language… We talk about a gender identity service now… Government had already committed to a clinic… We need more than just a clinic somewhere in Wales.(Participant 29, Equalities Organization)

Thus, in the present study, equalities organizations’ claims were described as targeting policy implementation directly, as well as the breadth of policy development stages illustrated above. This illuminates how equalities organizations advance claims to achieve substantive representation through the Partnership. Existing work tells us that complex policy processes open up multiple points for policy influence [110,111,112]. Collectively, these institutional discourses evidence that claims are made at these multiple stages of policy development and implementation, both with respect to equalities policies and bringing an equalities perspective to other policies. This accords with the definitions of mainstreaming that were detailed above. These claims are therefore evidence of mainstreaming being implemented through the Partnership.

The foregoing finding could also be interpreted as evidence of certain mainstreaming tools. For example, the equalities organizations’ claims accord with the mainstreaming tool of “visioning”, since these organizations were describing “how rules and practices need to be changed” to promote equality [18] (pp. 568–569). The foregoing analysis of claims could also be seen as reflecting a form of “Auditing”, insofar as the nonequalities policies were being assessed for their equalities implications. However, this focus on mainstreaming tools moves us from claims to claims-making activities. Thus far, the claims of equalities organizations have been examined. We shall now consider the formal claims-making activities of equalities organizations in the institution of the Partnership.

5.1.2. Accounts of Formal Claims-Making by Equalities Organizations

Interviewees consistently agreed that the formal policy-influencing activities used in the Partnership straightforwardly consisted of attending the Partnership meetings, as well as participating in the two planning meetings which preceded them. The planning meetings aimed to set agenda items and develop policy briefing papers to present in Partnership meetings. These accounts of formal claims-making differ from formal mainstreaming tools because the former simply document their involvement in the Partnership’s formal processes, whereas mainstreaming accounts specify a range of equalities policy tools.

Some equalities sector interviewees did touch on mechanisms that align with other mainstreaming tools besides those previously mentioned, but not with respect to the Partnership. For example, equalities budgeting is a mainstreaming tool (referenced earlier), and it was raised by some equalities interviewees who described attending the Budget Advisory Group on Equality (BAGE). However, even though the interview questions concerned Partnership policy-influencing, BAGE did not form part of the formal Partnership, and was managed by a different government department. A similar case is found with respect to the mainstreaming tool of equality impact assessments (EIAs), to which many Welsh Government officials made reference. For example:

Every single policy that is developed across the organization [Welsh Government] has to include an Equality Impact [Assessment]… It doesn’t really need to be brought out as a subject. If it was raised at a Cabinet Secretary [Partnership] meeting [by the nonprofit sector saying] ‘Oh we’re concerned that equality was not taken into account.’ All we’d do is say ‘Well, effectively every policy has to have an Equality Impact.’.(Participant 15, Welsh Government)

Thus, many officials made it clear that Welsh Government undertook EIAs. However, this was not considered to be relevant to the Partnership meetings. Similarly, other mainstreaming tools featured in policy actors’ accounts, such as when they described the “Strategic Equality Plan Board” (SEP Board) (Participant 31, Equalities Organization). The role of the SEP Board, according to Welsh legislation [113], is for equalities representatives to assess Government policies and practices against its equalities duties and review the equalities statistics and indicators. Thus, the SEP Board aimed to ensure Government served a monitoring, auditing, and evaluating function as well as drawing on data and equality indicators, which are both mainstreaming tools. However, the SEP Board was also external to the Partnership. Evidently, such mainstreaming tools are in place in Welsh Government, but institutional discourses reveal that they do not form part of the Partnership.

Given that these mainstreaming tools sat outside of the Partnership structure, consideration needs to be made into whether policy actors perceived the Partnership to be a mainstreaming mechanism. When study participants were asked whether equalities mainstreaming was achieved through the Partnership, interviewees were overwhelmingly critical of the concept and described it as detrimental to promoting equality, as shall be shown. This was expressed across equalities organizations, WCVA, and Welsh Government. Many stated a concern about the term itself, as seen here: “I really worry about the word ‘mainstreaming’” (Participant 19, Welsh Government). It was viewed as a policy from the past by this equalities participant: “The danger of mainstreaming is that it gets shoved under a carpet until an official comes along and finds it… you’ve got people in the third sector tearing their hair out and saying, ‘No. We talked about this twenty-five years ago’”(Participant 24, Equalities Organization).

The history of mainstreaming in Welsh Government has been well documented. It includes its emergence in 1999, the formal government commitment to mainstreaming in 2004, and the publication of a revised Welsh Government Mainstreaming Strategy in 2006 [114]. Recently, it was discussed in the Welsh Government commissioned Gender Rapid Review publications that followed a commitment from the First Minister to make Welsh Government a “feminist government” [115,116]. Academic expertise to inform this review about international policy and practice led to a “mainstreaming” resurgence in policy discourses [117]. Despite its re-emergence, the majority of interviewees wholly resisted the term. Mainstreaming was seen to frustrate the advancement of equalities, so their rejection of it needs to be examined.

Mainstreaming was commonly criticized for being “a bit tick-box” (Participant 31, Equalities Organization). This is similar to a mainstreaming critique made by McRobbie [118] (p.155) who referred to it as “a technocratic-managerial strategy”. This is explained by the tendency for some government interviewees to conflate “equality impact assessments” (EIAs) with mainstreaming (Participant 12, Welsh Government). EIAs are just one mainstreaming tool.

Another concern was raised even more frequently which was that “mainstreaming is a code for doing nothing” (Participant 16, Welsh Government). This was explained by one equalities representative:

When people say they are mainstreaming equality… it’s like a thread through the tapestry and very soon that thread is lost, and no one can see it when you hold up the tapestry.(Participant 34, Equalities Organization)

This interviewee saw mainstreaming as removing the equalities focus from equalities issues. Other interviewees from both Welsh Government and equalities organizations offered a similar criticism, as can be seen in this official’s account:

We’ve said it is a cross-cutting issue. It’s embedded in everything we do… it’s so deeply buried in what we do that we never actually think about it.(Participant 16, Welsh Government)

Analysis of how “mainstreaming” was constructed in these accounts revealed it had become synonymous with everyone in government being responsible for achieving equality. This was perceived by policy actors to remove Welsh Government’s focus from equalities matters because “making something the responsibility of all sometimes makes it the responsibility of no-one” (Participant 29, Equalities Organization). Therefore, there is a shift in the meaning of mainstreaming in the institutional discourses away from how it is generally understood in feminist political science. This is “conversion”, whereby an equalities strategy is co-opted and reinterpreted by institutional processes to a new goal [86,119].

The significance of this to our research question is as follows. Policy actors resisted any suggestion that the substantive representation of equalities interests achieved in the Partnership is associated with a mainstreaming strategy. This is notwithstanding the clear evidence of how equalities claims are embedded across the policy-making processes of government. This was because interviewees’ understanding of “mainstreaming” had distorted in practice from how equalities scholars understand the term. The implications of these findings for mainstreaming theory are picked up in the discussion below (Section 6).

This section has recognized the perception of formal claims-making activities as simply attending partnership planning meetings to develop the Partnership’s agenda, but it has also shown that the policy influencing tools of mainstreaming are not perceived to form part of the formal claims-making activities of the Partnership. Thus far, we have considered the claims and the formal claims-making of the equalities organizations. In line with our new institutionalist approach and in order to extend our understanding of substantive representation of equalities interests in the Partnership, attention now turns to informal policy-influencing.

5.2. Informal Policy-Influencing by Equalities Organizations

5.2.1. Accounts of Equalities Organizations’ Informal Claims-Making

Policy actors’ accounts from both Welsh Government and the nonprofit sector detailed the importance of informal relationships to nonprofit sector–government relations. As this official explained: “100-98% of our relationships are informal” (Participant 12, Welsh Government). The policy actors understood these informal relations to take place in the form of communication outside of the formal partnership meetings, as seen here:

[At meetings] smoothing is done, people are thanked for their contribution and things are signed… but the real hard work should be done outside of the meetings… There is a perception… that, in order to get anything done, you’ve got to talk with the Minister to change things. To a certain extent that’s true, but that misses out the role of the civil servants.(Participant 1, Welsh Government)

This excerpt demonstrates that informal communication was important between the nonprofit policy actors and both Government ministers and officials. Moreover, the nature of these informal relations was to have regular, reciprocal contact, as described here: “We have brilliant relationships with the civil servants… we’ll consult with them… seek their advice… use them as critical friends for reports or consultations” (Participant 39, Equalities Organization). This is typical of their accounts of using regular informal contact to build the relationship. Once informal relationships with officials were secured, the nonprofit sector could then become the contact that the official would informally call on for help. For example, they might be asked to help write government publications, as this equalities interviewee explained: “We’ve worked directly with the civil servants producing the… [named policy]” (Participant 41, Equalities Organization). This process of helping an official draft a government document was also described by another equalities representative: “We drafted it and they then put it in more or less as we asked” (Participant 40, Equalities Organization). They also might be consulted at an even earlier stage, as this official elucidated:

As a civil servant, I used to have no qualms at all about picking the phone up… and saying ‘this is something that’s going to be happening, I wondered how you thought that would go down?’… And it’s quite handy to have that knowledge before you irrevocably commit to do something.(Participant 1, Welsh Government)

Thus, according to these institutional discourses, being consulted on policy ideas and authoring sections of government documents is a direct result of these informal relationships. These are themselves important policy-influencing activities, but they also secure future leverage between individuals. As these equalities interviewee explained, it is “mutually beneficial” and “about the reciprocity” (Participant 27, Equalities Organization). One interviewee described how requests for help are “welcomed and returned” (Participant 39, Equalities Organization). This “reciprocity” is central to reinforcing their positioning.

Harnessing the “mutual benefit” as a key to developing informal relationships is a familiar trope in nonprofit literature, e.g., [120]. It has previously been recognized as information being exchanged “for access to policy makers” [121]. However, the present study reveals a more complex mutual exchange of advice and editorial influence on each other’s documents. These informal reciprocities present opportunities for the state to gain expert input into policy-making whilst the equalities nonprofit sector gain policy influence, and this simultaneously reinforces these informal relationships, thereby strengthening the formal partnership. This reflects the complex relationship between the informal and formal facets of the the institution of the Partnership.

Furthermore, policy actors spoke of how these informal relationships were sustained. An example of how to sustain informal relations was described by government officials, who wanted the sector to acknowledge “whether we’re government or whether we’re the third” there was a “common goal” (Participant 20 Welsh Government). As this official described:

We’re all part of the same jigsaw… I think you need people who accept that they are part of delivering for the people of Wales… We’re all part of the same team… doing slightly different bits of the job.(Participant 12, Welsh Government)

This is typical of the institutional discourses from officials, WCVA staff, and some equalities organizations. Therefore, commonality of aims is an important quality for equalities representatives to show in order to develop their informal relationships with government.

The nature of this common goal was variously described as to “support the most vulnerable people in society” (Participant 12, Welsh Government). Another official observed:

Fundamentally the Government… is made up of people who do really… care about inequality, poverty and are committed to trying to do something about it… so it’s about trying to… facilitate them looking through… the equalities lens.(Participant 19 Welsh Government)

Therefore, some officials saw equality and fairness as part of the government’s motive for engaging with the Partnership. The significance of these informal policy influencing activities to promoting substantive representation and this commonality of equalities-themed goals as a means to maintain informal relations will be expanded in the discussion below.

We next consider what these accounts of informal claims-making to achieve substantive representation reveal about the positioning of equalities organizations on the insider–outsider spectrum. As a formally designed nexus between civil society and government, the Partnership might be seen as offering an insider position to participants. We now turn to consider the extent this was reflected in institutional discourses of the nonprofit sector’s positioning.

5.2.2. Positioning and Policy-Influencing Strategies

When asked about claims-making in the Partnership, many policy actors reinterpreted the question to describe their influencing strategies outside of the Partnership. For example:

Can I just say that we, as [a particular equalities strand], have also a separate engagement mechanism with government… If this is all going to be about TSPC it won’t be covered.(Participant 23, Equalities Organization)

This interviewee drew attention to a non-Partnership mechanism. Other policy actors’ accounts of claims-making also went beyond the Partnership’s scope, despite the question’s specific focus, and they would reference any influencing activities that were employed with devolved government. An example of this was in developing informal relationships; equalities interviewees described issuing invitations to either ministers or officials to “get them out of their government building… for day trips” (Participant 27, Equalities Organization). Such activities were outside of the Partnership, as was having informal conversation with ministers at events, which is described here:

I said [to the Minister] we’re working on this and when it’s at a point in time, I want to be able to bring [it] to you’.(Participant 27, Equalities Organization)

This interviewee described later raising this agenda item at a formal meeting, which shows how informal influencing stretched beyond the Partnership but tied in with it.

Interviewees from equalities organizations identified other action repertoires, such as producing “detailed reports” with clear recommendations to government on “what actions need to be taken” (Participant 30, Equalities Organization). These were not restricted to the Partnership. They were used in multiple venues across government and devolved governance more widely, in which equalities organizations would present their publications’ findings in meetings (Participant 40, Equalities Organization). Alternatively, formal “letters” might be a Partnership agenda-raising tactic (Participant 1, Welsh Government) but also used externally as direct communication “to ministers” or “officials” (Participant 23, Equalities Organization) or even to a “committee” in Senedd Cymru (Participant 2, Senedd Cymru). This explains why the equalities nonprofit sector struggled to identify claims or claims-making used solely within the Partnership, as distinct from those undertaken in other policy-influencing venues. The construction of the question did not accord with how they understood policy-influencing activities.

The difficulty key actors had in confining their accounts of substantive representation to the Partnership tells us that the workings of the Partnership need to be understood in their wider governance context. This offers a more comprehensive, sophisticated understanding than is possible from a discrete examination of the Partnership without reference to the wider context. It is in keeping with the argument made by Macmillan and Ellis Paine [122] (p. 19) that a “plural conception of context” can inform our understanding of nonprofit sector strategies in their relations with the state. It led to a significant finding of this study, which is the recognition of the multiple positions that the equalities nonprofit sector held and adopted simultaneously to influence government.

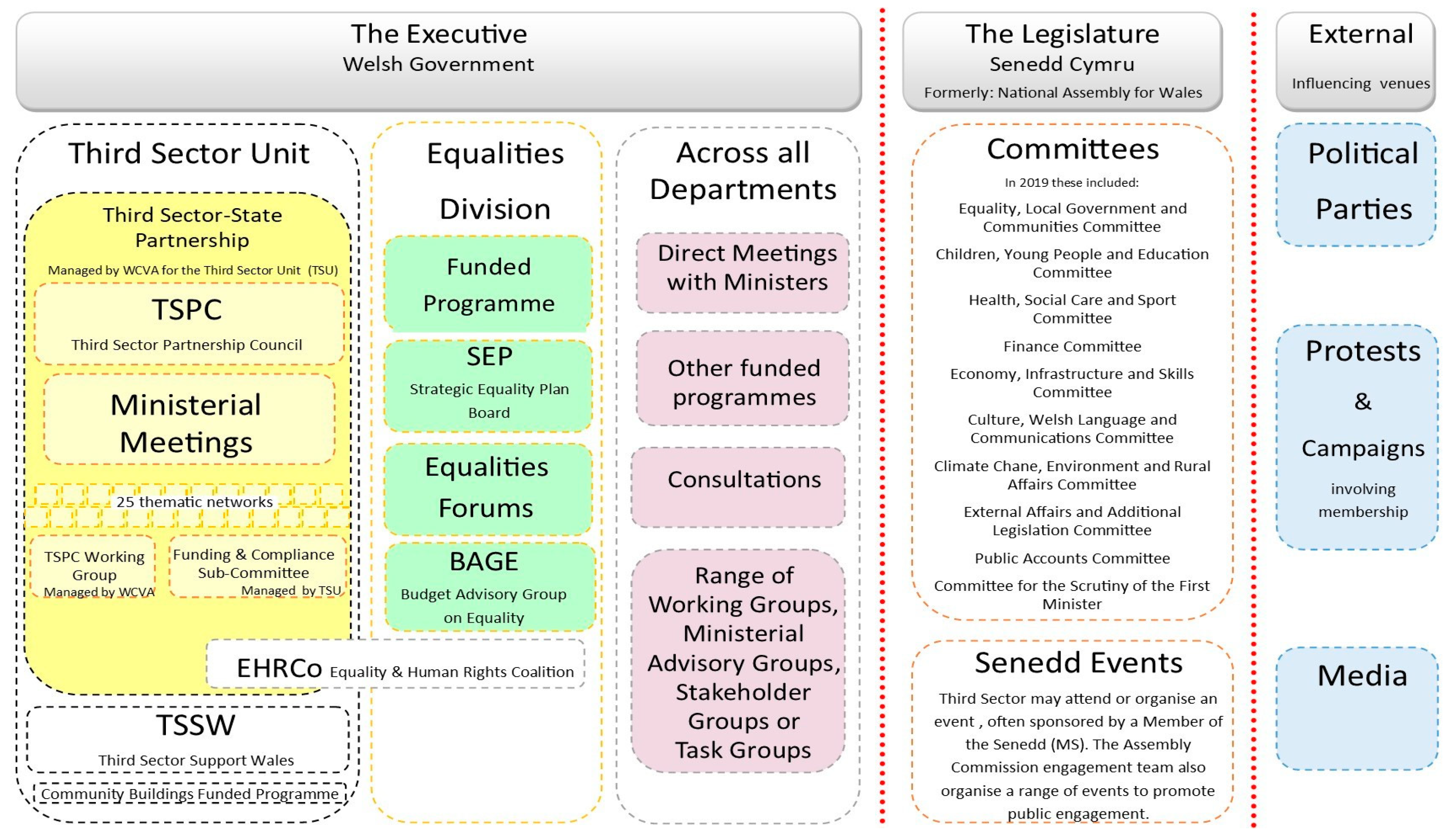

Interviewees’ extensive accounts made it possible to map out the policy-influencing venues used by equalities organizations, as seen in Figure 1. This locates the Partnership (left column, yellow box) within the context of the extensive mechanisms through which the sector engaged with the executive and legislative branches of devolved government. As Figure 1 reveals, the other influencing venues in Welsh Government included its Equalities Division, the sector’s direct meetings with ministers, Welsh Government policy consultation exercises, the funded programs from across Government in which equalities organizations delivered services, and a wide array of working groups or task groups that provided opportunities for other meetings with ministers or officials. All of these were distinct from engaging with the legislature, Senedd Cymru, where equalities interviewees also undertook influencing activities through the various scrutiny “committees” (Participant 37, Equalities Organization) or “events” in the Senedd (Participant 38, Equalities Organization). Notably, prior to 2006, the Partnership had previously sat within the Senedd, or the Assembly as it was then known. These findings suggest that the innovation of having such a formal partnership in place between government and the third sector has led to a collaborative way of working that extends out across the devolved government and well beyond the confines of the Partnership itself.

Figure 1.

Policy-influencing venues in devolved governance accessed by equalities nonprofit sector organizations.

Beyond these formal mechanisms the equalities organizations also detailed other action repertoires (right column). For example, they cited producing their “own manifesto” to coincide with national elections (Participant 36, Equalities Organization). They also described lobbying across political parties and attending “party conferences” to influence political party manifestos (Participant 36, Equalities Organization). Furthermore, outsider strategies such as mobilizing members to protest “on the steps of the Senedd” (Participant 41, Equalities Organization) featured in interviewees’ accounts. Additionally, they spoke of how they used the media, as is described here: “If we think there is no other route that is going to effect change, then we use the media to try and push for change, which can be quite effective” (Participant 40, Equalities Organization). Again, such a strategy was used alongside other insider tactics, as this interviewee explained: “I think that media pressure does help move politicians” (Participant 32, Equalities Organizations). This reveals the breadth of the multiple positions on the insider–outsider spectrum used by equalities organizations. We now consider how these multiple venues are used in order to understand the part the Partnership plays in this.

A useful description of how substantive representation by equalities organizations should be understood was offered by one interviewee, who stated “It’s about chipping away at those policy developments” (Participant 24, Equalities Organization). As another interviewee explained, policy changes “come about, just by years and years of lobbying, engagement, speaking” (Participant 31, Equalities Organization). One participant recalled “I lobbied and lobbied and raised it until people were sick of me” (Participant 34, Equalities Organization). The lobbying literature recognizes the need for relationships to be sustained over time [121], but this finding shows that these multiple venues are fundamental to the process. This notion of “chipping away” through multiple policy-influencing venues is a meta-action repertoire of the equalities nonprofit sector.

Given our research question is concerned with how equalities organizations engaged with the Partnership to promote substantive representation, it is important to explain how the above finding about multiple venues contributes to this. An equalities interviewee described the Partnership as “one tool in the toolbox” (Participant 32, Equalities Organization). One aspect of this “tool” of the Partnership is that it enables equalities organizations to position themselves, which is apparent because positioning strategies underpinned interviewees’ accounts of their action repertoires in the Partnership. Positioning techniques identified in the institutional discourses included taking part in one of the Partnership’s two sub-committees: The working group of the Third Sector Partnership Committee (TSPC), which was managed by WCVA, and the Funding and Compliance Sub-Committee, which was managed by Welsh Government. These are seen in Figure 1 (left column). As this equalities representative explained:

I guess everyone on the working group probably had quite a lot of influence… They are setting the agenda and shaping the mechanisms.(Participant 8, Equalities Organization)

However, some institutional discourses reveal the access to government the Partnership provided to the nonprofit sector stretched beyond the Partnership itself. Thus, the Partnership was useful for equalities organizations to secure positions in other governance settings, as this interviewee described: “I often find myself invited to things, where Government have mini Task and Finish groups … and they’ll think ‘Quick we need a third sector person’” (Participant 27, Equalities Organization). This illustrates how being a Partnership member automatically provides access to other policy-influencing venues. Other equalities interviewees revealed they actively used the Partnership to campaign for the nonprofit sector to access positions in other settings. For example, this equalities interviewee stated:

We tried a number of times to try and get onto the Curriculum Strategic Forum… It took two years through the TSPC…We got onto it… So, through the TSPC… that was successful.(Participant 34, Equalities Organization)

The above illustrates the TSPC element of the Partnership being used in a claim to participate in the wider policy-making machinery of government. Thus, having such a partnership institution in place enabled equalities organizations to develop sophisticated positioning strategies in order to promote substantive representation.

Furthermore, these results show how the Partnership enabled multiple venues to be accessed simultaneously by equalities organizations. In this respect, we are drawing on venue-shopping theory, which proposes organizations are able to strategically switch institutional venues to achieve policy outcomes [26,27]. When this theory is applied to the insider–outsider spectrum, it underlines the choice of venues available to equalities organizations which range across the insider–outsider spectrum (as identified in Figure 1). One example of how this strategic switching of venues can be understood was described by this WCVA interviewee:

So, at the last meeting… we did the paper [about disability concerns related to taxi licensing]. Actually, then three days later it was an item on the BBC Wales news at 6 o’clock. Which was great because the Minister got up and said exactly the same as he had said in the meeting. I think the Minister was comfortable because we had raised it directly with him three days before, so he had had the chance [to develop his response]… That to me is clever work. Rather than just going straight to the public and getting the Minister’s back up… actually doing it directly… and then… doing the public bit, just to make sure the extra bit of pressure is on.(Participant 5, WCVA)

This participant’s account of the nonprofit sector raising the issue in the Partnership meeting prior to it reaching the national media illustrates how the equalities organization deployed their multiple influencing positions. The example above shows the nonprofit sector levering the external media against the executive, whilst maintaining their insider position through the formal mechanism of the Partnership. In turn, this enabled them to be critical whilst sustaining their informal good relations with government. Thus far, we have considered how the equalities organizations engaged with the Partnership to promote substantive representation. We give final consideration to how the institution of the Partnership might shape these equalities organizations’ policy influencing activities.

5.3. Power and Constraints on the Nonprofit Sector’s Substantive Representation

The foregoing analysis suggests that the nonprofit partners were able to sustain their critical voice and that this was enabled by the partnership rather than constrained by it. The equalities organizations’ own accounts supported this, since they maintained that they felt able to be critical of government. As this interviewee from an equalities organization reported “I don’t feel restricted in any way at these meetings” (Participant 29 Equalities Organization). They consistently made statements such as: “if I feel I have to say something I will say it” (Participant 26, Equalities Organization) and “I think that’s what we’re there for” (Participant 33, Equalities Organization). This challenges the critique that nonprofit organizations with a close relationship feel constrained in their ability to be critical of the state.

Notwithstanding this finding, there were many other instances of the nonprofit partners policy claims being constrained by normative expectations within the Partnership institution concerning “behavior that is appropriate” (Participant 6, WCVA). One example is the constraint on raising issues to do with nonprofit sector organizational needs in Partnership meetings. Notably, officials described funding-based claims as a past blight on Partnership business, which had been eradicated, as is revealed here:

There’s been a lot of meetings in the past …whereby the sector is basically asking for more money… Fortunately, we’re not there anymore… We don’t want them to say things in a meeting that’s going to damage them, like ‘Just give us more money’.(Participant 18, Welsh Government)

This notion that funding-based claims would “damage” the nonprofit sector indicates how such claims were discouraged. As this equalities interviewee stated, “asking for money…I think kind of got banned in the end” (Participant 8, Equalities Organization). This certainly stands at odds with the commitment that underpins this Partnership which is found in both the Government of Wales Acts (1998, s114.4; 2006, s74.4,). i.e., to provide and monitor “assistance” to the sector and “consult” them on “matters affecting or of concern to” them. Moreover, this institutional norm was accepted by the nonprofit sector participants, as this equalities representative explained, “We’re not there to make special pleading on behalf of those organizations that we’re employed by” (Participant 24, Equalities Organization). This individual goes on to elaborate how this norm is enforced with new attendees:

I remember going to my first [Partnership meeting] and being shot down for talking about something specific and I think that it’s an important lesson because you’re there as a collective, you know. Special pleading isn’t allowed.(Participant 24, Equalities Organization)

Thus, pursuing individual organizational needs was seen as “feathering their own nests and protecting their own interests” (Participant 11, WCVA). Consequently, the sector was cautioned against raising financial concerns, as this official explained: “They have to be really careful… otherwise they can be seen as whinging… if everyone is just saying ‘You’re not funding us enough,’” (Participant 19, Welsh Government).

Such claims were often portrayed as irritating for Welsh Government ministers with the potential to damage their relationship with the minister. Thus, the onus was on the sector to respond to the willful characters of the ministers since, as this official explained, “Politicians and our cabinet secretaries are their own people. They are a law unto themselves” (Participant 20, Welsh Government). Relatedly, the nonprofit partners were described as needing to be “strategic thinkers” (Participant 12, Welsh Government) and “politically astute” (Participant 1, Welsh Government), as is illuminated by this equalities interviewee:

It is actually a skill … Somebody can be brilliant at the diplomacy in these kind of meetings…. There’s a knack to playing the sides, [and] understanding the politics, with a small p, of Government, and what they are trying to achieve and the egos within that world, and the necessities to get things done.(Participant 27, Equalities Organization)

This excerpt relates responding diplomatically to “the egos” within government to efficacy in terms of “getting things done”. Whilst being compliant with such behavior expectations may expediate their policy influencing in one respect, critical thought should be applied to the notion that it is strategic for the nonprofit sector to accept such constraints on their behavior. The implications of accepting such constraints in a collaborative partnership such as this are expanded on in the discussion below.

6. Discussion

Our institutionalist approach led to this study’s examination of how substantive representation was pursued both through formal and informal claims-making by the equalities nonprofit sector. In the empirical analysis, formal policy-influencing through the Partnership was analyzed with reference to policy-influencing tools described in the mainstreaming literature. This revealed that the Partnership itself exhibited limited use of mainstreaming tools, although there was evidence of their use in Welsh Government outside of the Partnership (Section 5.1.2). A further key finding was wide rejection of mainstreaming as a strategy for advancing equalities by a broad spread of study participants. However, scrutiny of the equalities organizations’ claims revealed that they were made at multiple stages of policy development and were concerned with both equalities policy-making and bringing equalities considerations to broader policy-making agendas. These institutional discourses were consistent with mainstreaming theory and ensuring equalities claims have “systematic integration into all systems and structures, into all policies, processes and procedures” [18] (p. 560). The theoretical contribution this makes is that it demonstrates it is possible to achieve mainstreaming aims without widespread support from some policy actors for mainstreaming or use of mainstreaming tools.

The empirical finding that mainstreaming was largely rejected as an appropriate strategy by interviewees from across government and the nonprofit sector, even by equalities organizations themselves, is worth considering further. Its rejection was shown to be related to a reinterpretation of the meaning of “mainstreaming” by policy actors. The empirical analysis of the informal institutional discourses of interviewees showed that the meaning of mainstreaming had erroneously been redefined in two alternative interpretations: either as simply referring to the use of equality impact assessments (EIAs), or to mean everybody shares the responsibility of pursuing equality. In the case of the former, the conflation of mainstreaming with EIAs led to its rejection on the grounds of it having limited impact. Mainstreaming theorists have explained that mainstreaming is often confused with one or more of its component tools [18], especially EIAs [18,73], so this discourse has previously been recognized. In the case of the second rejection of mainstreaming, policy actors across the sample of interviewees saw mainstreaming as losing the equalities focus in policy work. This second reinterpretation of mainstreaming as the diffused responsibility for equalities has hitherto largely been overlooked in mainstreaming theory. Feminist political scientists have written extensively about the success or failure of mainstreaming strategies to instigate meaningful advancement of equalities [73,75,118,123]. They have also sought to understand why mainstreaming strategies have fallen short of their transformative potential [123]. Thus, this reinterpretation of mainstreaming can contribute to contemporary explanations about reported failures in the efficacy of mainstreaming in institutional settings. Related implications for mainstreaming in practice are discussed in the conclusion.

The institutionalist analysis of this study underlines the significance of informal repertoires in policy-influencing and how they complement the formal institutional practices. The analysis revealed this informal claims-making was extensive in and around the institution of the Partnership. Notably, this was acknowledged and accepted by Welsh Government, WCVA, and the equalities nonprofit sector interviewees. Consequently, policy actors detailed the development and maintenance of informal relationships between the equalities nonprofit sector and Welsh Government officials and ministers. Whilst the mainstreaming literature has developed extensive accounts of formal policy-influencing tools [17,18,19], the theoretical significance of this finding is that there has been less scrutiny of the role of informal strategies. The institutionalist lens of this study enables us to recognize the role of such influencing strategies and informal relationships between the equalities nonprofit sector and government in addition to the formal policy-making processes.

Nonprofit literature has recognized informal relationships between organizational representatives and politicians, but it is commonly seen as covert, involving “lurking in corridors” [124]. For example, Chaney [125] described such informal communication as a “pathology” because it potentially represents a “democratic ill” which is “neither transparent nor accountable” due to it being outside of “the formal political channels”. Much of the literature on informal politics assumes it can “weaken” or “impede” governments [126] and hence is “condemned as arbitrary, unfair or corrupt” [127]. Yet the accounts above demonstrate that these informal strategies were openly cited by both government and nonprofit sector interviewees. They portray informal relations as expected and acceptable rather than underhand. Instead, the literature on influencing strategies resonates with the present case study because it recognizes informal networks as legitimate where the combination of informal channels and formal meetings are viewed as the two halves of lobbying [54].