Abstract

The search for the origins of COVID-19 has yielded no conclusive evidence. In the face of this uncertainty, other social and political factors can influence perceptions of virus origins, which in turn can influence policy formation and global efforts to combat future pandemics. Vastly different COVID-19 origin stories may circulate both within the same country but also between different countries. This article examines COVID-19 origins debates as they circulate in China, drawing from a 974-respondent survey conducted in mainland China. Our results show that within China there is a strong belief that COVID-19 originated outside the country, either in the United States or Europe. This contrasts with mainstream media coverage in the United State and Europe, which generally holds that the virus most likely originated in China. Given such global dissonance, moving forward with pandemic prevention reforms is challenging. Yet, even in the face of such diverse beliefs, building support for reform is still possible. As the search for COVID-19 continues, policy reform can be pursued across a plurality of domains, including wet markets, the wildlife trade, cold-chain products, and gain-of-function virology research, all in the interest of preventing the next global pandemic.

1. Introduction

The pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2, causing the disease COVID-19) has yielded widespread public health, economic, and environmental impacts [1,2]. Where and how the virus first emerged, however, remains unclear. Uncertainty over virus origins has instigated not only scientific debate, but also a proliferation of speculative hypotheses in the media and in public discourse [3,4]. These hypotheses can differ drastically according to social and political context, both within and between countries [5,6].

Initially, the first human transmission of COVID-19 was overwhelmingly thought to occur from wildlife sold at the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, China [7]. Consequently, China temporarily shut down all wet markets and banned terrestrial wildlife farming on 26 January 2020, followed by a comprehensive and more permanent ban on February 24. Subsequent investigations, however, have cast doubt on the Huanan market as ground zero for COVID-19′s first human transmission. As early as January 2020, cases with no relation to the market were identified [8,9], a finding further confirmed by the World Health Organization (WHO) investigation report in March 2021 [10]. More recently, studies have reaffirmed the Huanan market as the “unambiguous epicenter” of the virus [11], although not necessarily the site of initial human-to-animal transmission [12]. Continued lack of certainty over virus origins has contributed to the proliferation of alternative origin stories that do not necessarily involve zoonotic transmission.

The most prominent among these alternative origin stories is what has become known as the “lab leak” hypothesis [13,14]. As circulated in the United States and Europe, the lab leak hypothesis posits that COVID-19 was accidentally leaked from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, eventually leading to the outbreak at the Huanan seafood market and across the world [13,15]. The lab leak hypothesis circulates, too, within China, but it posits another chain of events not at all related to the Wuhan Institute. This version indicates the virus may have leaked from Fort Detrick, a biomedical research site located in Maryland that the CDC shut down in August 2019 because of failure to follow safety standards [16]. Soon after this, in October 2019, American military personnel visited Wuhan to attend the Military World Games. It is suspected that these personnel first brought the virus to China [17].

Another hypothesis circulating in China—the “cold chain” (冷链, lěng liàn) hypothesis—also reinforces the possibility that COVID-19 originated overseas. This hypothesis points to evidence that COVID-19 can be transmitted on the surface of frozen or refrigerated meats and thus the real origins of COVID-19 may be far from Wuhan or may even lie outside of China. Indeed, a number of local outbreaks in China have been linked to frozen foods imported from abroad with significant media coverage [18]. Based on these outbreaks, in November 2021 the Chinese government began requiring disinfection of imported frozen goods as a preventative measure [19]. The cold chain hypothesis, similar to the version of the lab leak hypothesis that circulates in China, contributes to the perception that COVID-19 may not have originated in China.

Perceptions of where and how COVID-19 originated affect policy formulation, further impacting efforts to address future pandemics [20,21]. While alignment in public perceptions can lead to coordinated action and improved pandemic preparedness, a lack of consensus and a rise in conspiratorial thinking can lead to the opposite outcome [22]. In both cases, media has a strong role in influencing public opinion, public sentiment, and politicization [9,23]. In the case of the search for COVID-19 origins, heightened politicization exacerbated by mutual distrust may undermine the cooperation and information sharing necessary for a globalized response to prevent future pandemics [24,25].

This article examines perceptions of COVID-19 origins in China, noting some of their obvious differences from origin perceptions widely held in places such as the United States and Europe. Given the proliferation and divisiveness of COVID-19 origin stories within countries such as the United States, we suspected that potentially larger discrepancies may exist between countries. Our work builds on the rapidly emerging literature surrounding the politics of COVID-19 in the age of post-truth, politicization, and conspiratorial thinking [4,22,26]. Through an opinion survey covering 974 respondents across mainland China in June 2021, supplemented by a media review, we find that more than half of total respondents (65%) believe COVID-19 originated not in China, but rather overseas in the United States and Europe, from a variety of sources, including wet markets, wildlife farms, laboratories, and imported frozen foods. Yet, despite this belief, respondents demonstrate strong support for reforms within China across a variety of other domains (wet markets, virology research, and the frozen foods supply chain). Overall, our research finds that although many respondents in China believe COVID-19 originated overseas, there is nonetheless strong support for a range of policy reforms within the country to prevent the outbreak of future pandemics.

2. Methods

This article draws from survey data collected in June 2021 from 974 respondents across mainland China, supplemented by a media review using the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT). The survey consisted of 33 questions covering the origins of COVID-19, the wildlife trade, and different policy responses to guard against future outbreaks. Our media review, which supplements the survey, focuses on coverage of different COVID-19 origin stories in China. Both the survey and the media review are intended to better understand perceptions of virus origins in China and to summarize and introduce these perceptions to English-speaking audiences outside of China that, by and large, have little awareness of how COVID-19 origins are narrated in the most populous country on Earth.

The survey was executed using the Qualtrics online platform with a sample of respondents that match the demographics of mainland China by gender and age (with the exception that all respondents were above 19 and below 80 years old; see Table 1). This quota sampling method has limitations and may potentially introduce new biases in the data collection process, as respondents who do not meet the quota are discarded [27,28,29]. In our case, we used quotas to include male and female respondents of various age groups that are roughly representative of mainland China as a whole (based on China Statistical Yearbook 2020 data).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents (N = 974) across mainland China.

The survey was written in English and translated to Chinese by a member of the research team and verified by another member of the research team. Prior to executing the survey, two pre-tests were conducted in order to ascertain translation clarity and survey validity. The first pre-test was conducted with a convenience sample of 133 respondents (mainly Chinese-speaking academics) in December 2020 and January 2021. The second pre-test consisted of a “soft launch” of 50 respondents from the Qualtrics panel (after which we paused data collection to assess the survey questions and data quality).

Respondents were recruited through the Qualtrics platform, which has experience in China-based sampling [30,31]. The sampling drew from a China-based panel of individuals recruited from diverse sources, such as website intercept recruitment, member referrals, targeted email lists, gaming sites, customer loyalty web portals, permission-based networks, and social media. Although respondents were recruited from diverse sources, they were all part of Qualtrics’ China-based panel. Respondents were all sampled from this single panel. Qualtrics validates panel members’ names, addresses, and dates of birth via third-party verification measures prior to their inclusion in the panel. Panelists are compensated through various mechanisms; they may be airline customers who choose to join in reward for SkyMiles, retail customers who opt to receive points at a retail outlet, or general consumers who participate for cash or gift cards. Panel members are given an email invitation or prompted to participate in a given survey on the respective survey platform.

In addition to quota sampling, other checks were used to filter out respondents who completed the survey without considering the questions at hand. These checks were based on Qualtrics standard quality control measures, including tracking time to completion and excluding respondents taking less than one third the median time to completion (as calculated during the survey soft launch). In addition to this standard protocol, ten additional screeners were added, excluding respondents who answered in an internally contradictory manner. These screening measures were determined based on illogical combinations of responses as a supplemental measure to exclude respondents answering questions arbitrarily without reading the questions beforehand. For example, one such screener excluded respondents who selected that they support a ban on trade in all wild animals, but then also selected that they do not support a ban for trade in a particular species.

Qualtrics sent the survey to a total 3789 respondents (including the soft launch, but not including our pre-tests). Many of these respondents did not qualify or ended up being over quota for the age and gender specifications or were screened out because of speeding through the survey or answering in an internally contradictory manner. A total of 1369 respondents were terminated because they were over quota (i.e., in an age range or gender category that had already met its quota) and a total of 1236 respondents were terminated for targetable attributes (i.e., were younger than 20, older than 79, were not located in China, or were screened out because of the supplemental screeners implemented, including 68 respondents excluded because of speeding through the survey). Qualtrics survey platforms send their surveys to such a broad audience that it is common to have more respondents terminate than complete the survey, as was the case in this survey. This left a remaining sample of 1184 good completes. Excluding the soft launch respondents from our sample, we were left with a total of 974 respondents used for our analysis.

The sample that we analyzed (N = 974) was diverse in terms of occupation (with relatively even representation from the eight primary occupational categories in China), income (with monthly income ranging from under CNY 1000 to over CNY 20,000), and education (ranging from middle school or below to post-graduate degrees, with 74% of respondents having college degrees) (Table 1 and Table 2.) The sample was less diverse in terms of urban versus rural (90.7% of respondents lived in urban areas), which represents a limitation in the sample, since it is not representative of China as a whole on this variable (as of 2020, just over 60% of China’s population lived in urban areas, according to World Bank data).

Table 2.

Occupations of respondents.

Responses were analyzed using STATA (version 15) in two steps. First, we generated descriptive statistics about perceptions concerning COVID-19 origins and support for various policy reforms. Second, we used logistic regression models to analyze the results. We used a multinomial regression model to first determine which demographic characteristics impact the odds of respondents reporting certain beliefs about where COVID-19 originated (compared to a baseline group of respondents that selected China as the believed origin) and we also calculated the percent change of probability of selecting multiple believed origins. In this analysis, the dependent variable was the believed COVID-19 origin region (China, Europe, US, etc., with respondents only able to select one response) and independent variables included the demographic variables of gender, age, education, and income. We then used a binary logistic regression model to determine which demographic characteristics impact the odds of whether participants changed their minds about where they believe COVID-19 originated (compared to a baseline group of respondents that did not change their mind about COVID-19 origins) and the percent change of the probability of changing one’s mind. In this analysis, the dependent variable was whether or not a respondent changed their opinion about COVID-19 origins (yes or no) and the independent variables were the same demographic variables.

Lastly, we performed logistic regression using the believed region of COVID-19 origins (China, Europe, US, etc.) and demographic variables such as the independent variable and the believed source of COVID-19 (wet markets, animal farms, natural causes, laboratories, etc., allowing for more than one response) as the dependent variable to analyze if respondents who believed COVID-19 originated in certain regions had greater odds of support for certain sources. The percent change of the probability of selecting one specific believed origin is also included in our analysis. We used a binary regression model because the dependent variable allowed for more than one selection. Using binomial regression, we cannot draw conclusions on the odds ratio change between different sources due to the variation of independent variables. We can only see the relationship between the independent variables and the odds of choosing one particular source.

Survey data was supplemented by a longitudinal review of COVID-19 origins coverage in Chinese media from the beginning of the outbreak until 10 September 2021. For media analysis, we used GDELT to track media articles concerning the origins of COVID-19 published in the Chinese language within mainland China. The number of articles that contained (1) “virus” and “wild animals”, (2) “virus” and “cold chain”, and (3) “virus” and “laboratory leak” were tracked from 1 November 2019 to 10 September 2021. Using this output, we also identified key moments in the media coverage of COVID-19 origins.

3. Results

3.1. Survey Results

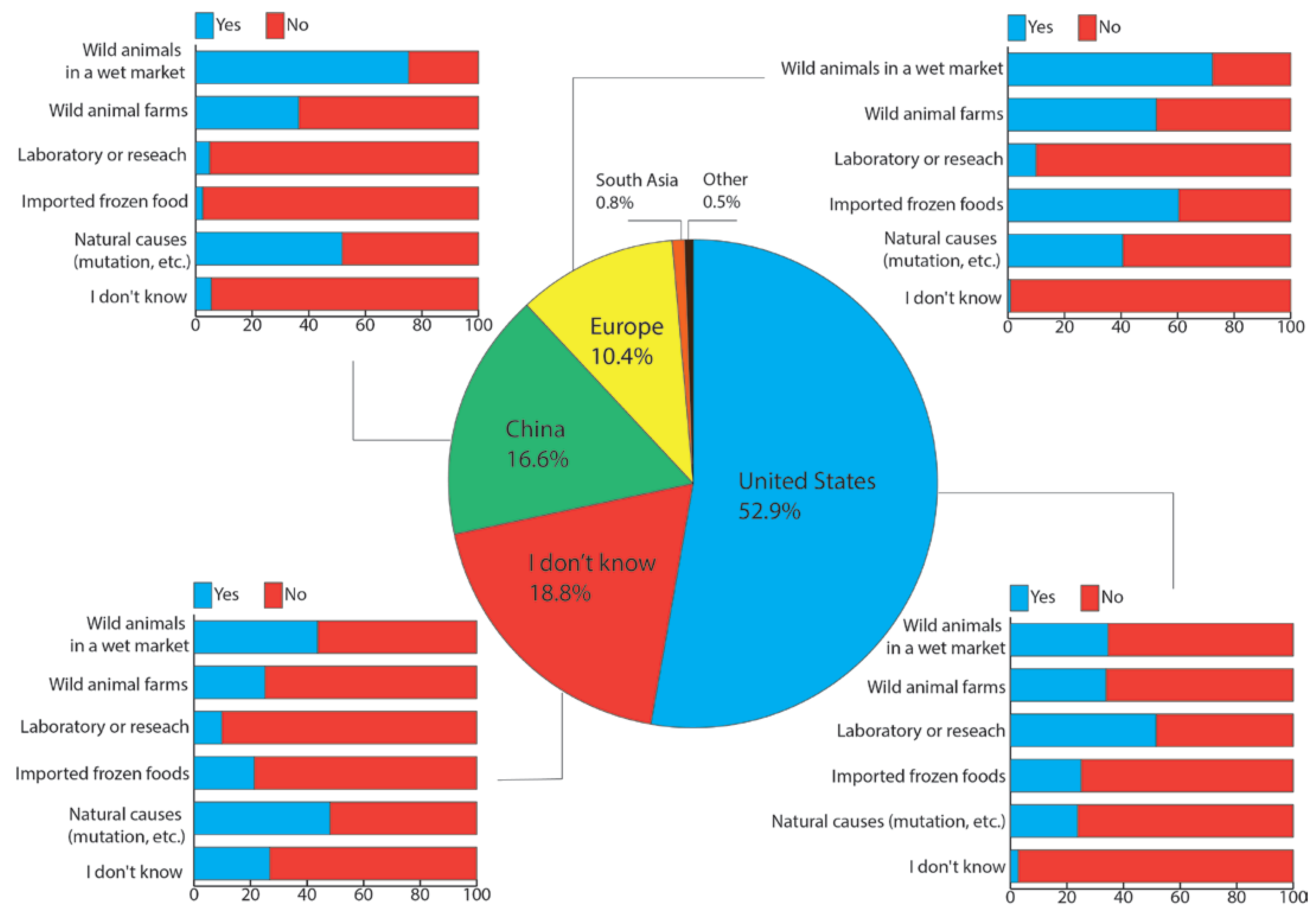

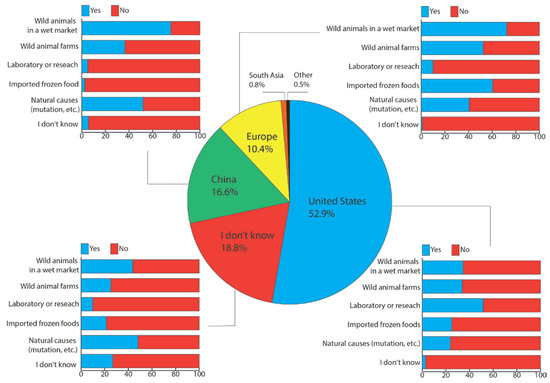

Our findings show that more than half of total respondents (53%) reported that they believe COVID-19 originated in the United States (see Figure 1, pie chart). This is compared to only 17% of respondents who reported they believe the virus originated in China, 19% who reported that they did not know where it originated, and 10% who reported it originated in Europe.

Figure 1.

COVID-19 origins according to survey respondents. The pie chart in the center illustrates responses to the question “Where do you think COVID-19 first emerged?” for all 974 respondents across mainland China. The stacked bar graphs in each corner illustrate responses to the question “Which of the following sources do you think COVID-19 most likely originated from?” for each group of respondents according to their responses for where COVID-19 emerged (those respondents who indicated the virus originated in China: top left; Europe: top right; US: bottom right; I don’t know: bottom left). “Yes” indicates respondents selected the option as a likely source, “No” indicates respondents did not select the option, with multiple selections possible.

In addition to where COVID-19 first emerged, the survey also asked how the virus emerged—whether through laboratories, wet markets, animal farms, natural causes, or imported frozen foods (the “cold chain” hypothesis). Respondents were allowed to select as many sources as they thought applicable, with many respondents selecting more than one. Our findings here point to a diversity of COVID-19 origin stories (Figure 1, bar charts). Perceived origin sources, however, differ according to perceived origin regions. Of those respondents who indicated China as the most likely origin (162), the majority (75.3%) selected wet markets as an origin source. Of those respondents who indicated the United States as the most likely origin (515), the majority (51.1%) selected laboratories as an origin source. When looking at the total sample, 27% of total respondents reported both the United States as the source country and laboratory or research as a likely source, indicating they believe the virus came from a lab in the United States, compared to less than 1% who reported both China and laboratory activities as a likely source.

Those respondents who indicated Europe as the most likely origin (a total of 101) also reported somewhat different likely sources. Of this group, 72.3% selected wild animals in wet markets (despite the fact that, as with the US, few such markets in Europe exist) and 60.4% selected imported frozen foods (likely suggesting that these respondents identified Europe as the initial source of the virus and frozen foods as the vehicle through which it was transmitted into China). Natural causes (40.6%) and laboratory or research (9.9%) were less commonly selected among this group as a likely source.

We ran binary logistic regression models to determine how believed origin region (China, United States, Europe, etc.) influenced the odds of believing that COVID-19 originated from a particular source (wet markets, wild animal farms, laboratories, etc.) (Table 3). We also analyzed the predicted probability changes of reporting initial sources of COVID-19 according to perceived origin locations and demographic characteristics (Table 4). We found that, compared to the baseline group of respondents selecting China as the origin, respondents who select the United States have much greater odds of selecting laboratory or research and imported frozen foods as a likely source, while these respondents have reduced odds of selecting wild animals in a wet market or natural causes. Selecting the United States as the origin region increases the probability of selecting imported frozen foods and laboratory or research as the origin source by 25.4% and 46.2%, respectively, while it decreases the probability of selecting wild animals in a wet market and natural causes as an origin source by 39.1% and 24.5%, respectively.

Table 3.

Odds of reporting initial sources of COVID-19 according to perceived origin regions and demographic characteristics.

Table 4.

Predicted probability changes of reporting initial sources of COVID-19 according to perceived origin locations and demographic characteristics.

Respondents selecting Europe as the origin region demonstrate similar trends. These respondents have greater odds of selecting imported frozen foods than the baseline group (even more than respondents selecting the United States) and greater odds of selecting laboratory or research (although not as great as respondents selecting the United States) compared to the baseline group. They also have slightly greater odds of selecting wild animal farms. Lastly, they also have reduced odds of selecting wild animals in a wet market and natural causes (although the effect is not as large as for respondents selecting the United States). Selecting Europe as the origin region increases the probability of selecting imported frozen foods and laboratory or research as the origin source by 41.3% and 9.2%, respectively, while it decreases the probability of selecting wild animals in a wet market and natural causes as the origin source by 15.6% and 15.0%, respectively.

Within these models, there were numerous significant demographic effects. We found that older respondents (40+) and urban residents have greater odds of selecting imported frozen foods as a source, with the effect intensifying with age. Older respondents (50+) have higher odds of selecting wild animals in a wet market and wild animal farms. Compared to the 20~29 age group, being in the eldest respondents (70+) category increased the probability of perceiving imported frozen foods as an origin source by 62.1%. Male respondents have reduced odds of selecting wet markets and wild animal farms as the source, with a decreased probability of selecting these as an origin source by 8.3% and 12.2%, respectively. Income also has an influence: mid-to-low-income respondents (under CNY 20,000) have increased odds of selecting laboratory or research and increased odds of selecting that they do not know. Being in the income category of CNY 10,000 to 20,000 increases the probability of selecting laboratory or research as an origin source by 15.3%. In contrast, respondents in these income ranges have reduced odds of selecting wild animals in a wet market, wild animal farms, and natural causes. Being in the income category of CNY 1000 to 5000 decreases the probability of selecting wild animal farms as an origin source by 49.5%. Lastly, education has some influence, with respondents with a high school degree or below having increased odds of selecting wild animal farms as a source. Compared to respondents with a college degree, being in these categories increases the probability of selecting wild animal farms as an origin source by 11.0% and 26.9%, respectively.

Next, we used a multinomial logistic regression model to determine the odds of reporting different origin regions (China, United States, Europe, etc.) according to demographic variables (Table 5), along with the predicted probability changes (Table 6). We found that age is a significant factor. Older respondents (60–79) have increased odds of considering Europe an origin (increase in probability by 17.5%), and the eldest respondents (70–79) have decreased odds of considering the United States an origin (decrease in probability by 33.2%). Income also has some influence; mid-income respondents (CNY 5000–20,000) had decreased odds of considering the United States or Europe as the origin. Being in the CNY 10,000 to 20,000 income category (compared to the over CNY 20,000 income group) increases the probability of selecting China as the region origin by 10.0% and Europe by 9.4%. Being in the CNY 5000 to 10,000 income category increases the probability of selecting China as the region origin by 9.2%, while decreasing the probability of selecting the United States by 15.6%.

Table 5.

Odds of reporting different origin locations of COVID-19 according to demographic characteristics.

Table 6.

Predicted probability change of reporting different origin locations of COVID-19 according to demographic characteristics.

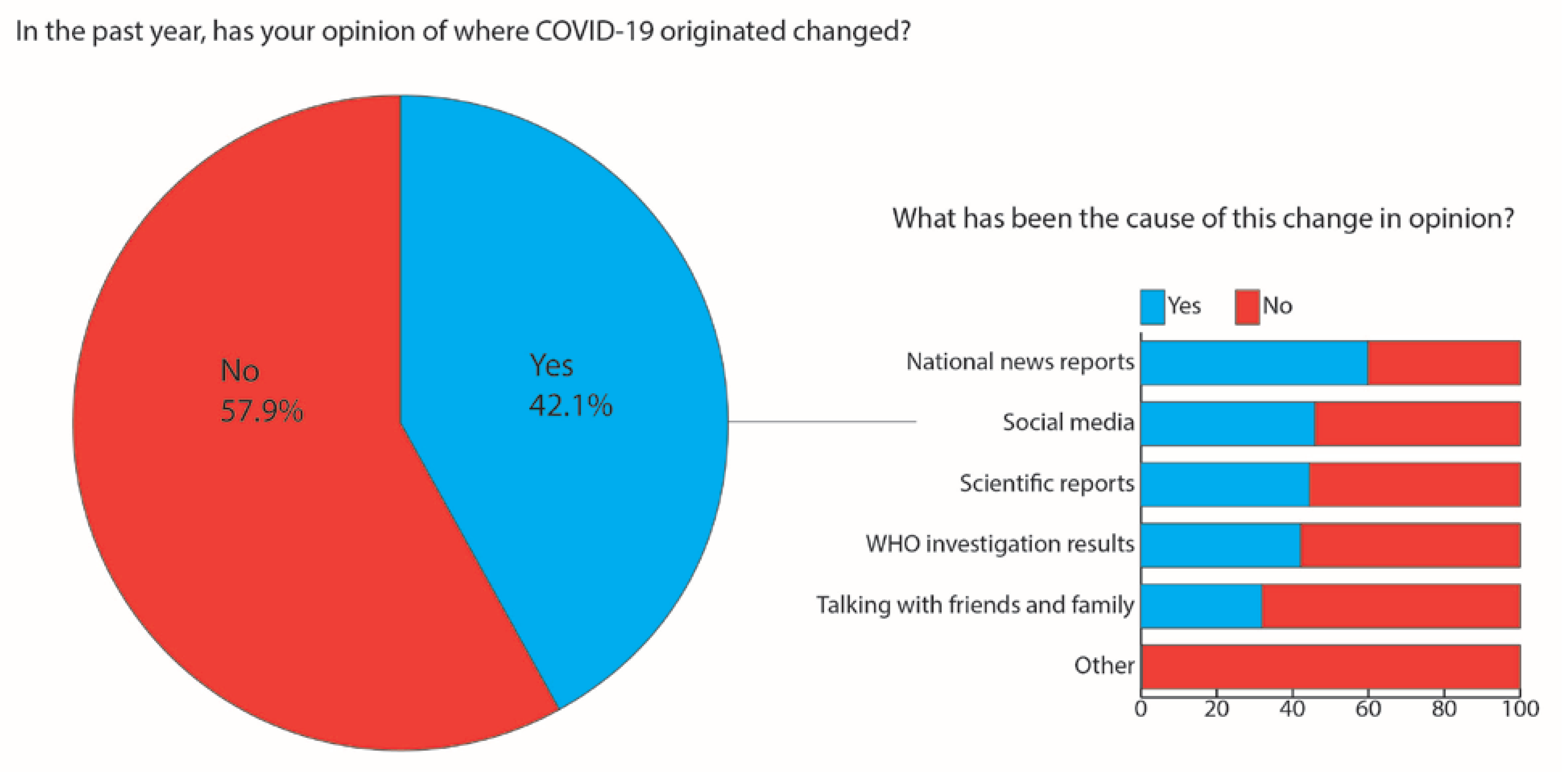

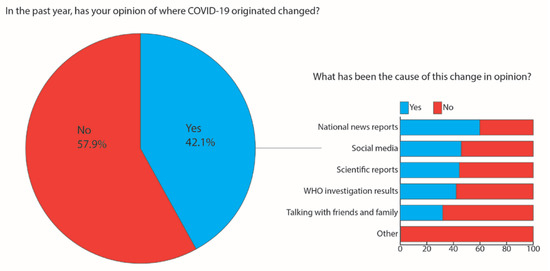

The survey also asked if respondents changed their mind about the origins of COVID-19 within the past year. Approximately 42% of respondents indicated that they had changed their minds, with various sources of information contributing to this opinion change (Figure 2). National news reports were the most frequently cited attributing factor (59.8% of respondents indicating a change in opinion listed this as a contributing factor), followed by social media (45.9%), scientific reports (44.4%), the WHO investigation (42%), talking with friends and family (31.9%), and other unlisted reasons (0.3%).

Figure 2.

Respondents who have changed their minds about COVID-19 origins in the past year reported cause of change in opinion. The pie chart illustrates responses to the question “In the past year, has your opinion of where COVID-19 originated changed?” for all 974 respondents across mainland China. The stacked bar graph illustrates responses to the question “What has been the cause of this change in opinion?” for those respondents who indicated a change of opinion. “Yes” indicates respondents selected that factor as contributing to their opinion change, “No” indicates respondents did not select that factor.

Our final binary logistic regression model was used to determine which demographic characteristics influenced the odds of whether participants changed their minds about where COVID-19 originated (Table 5, last column), along with the predicted probability change (Table 6, last column). We found that male respondents have lower odds of changing their minds about where the virus originated than female respondents; mid-income respondents (CNY 5000–10,000) also have reduced odds of changing their minds than high-income respondents (over CNY 20,000); and respondents with a graduate degree and middle school education or below have reduced odds of changing their mind compared to those with college degrees.

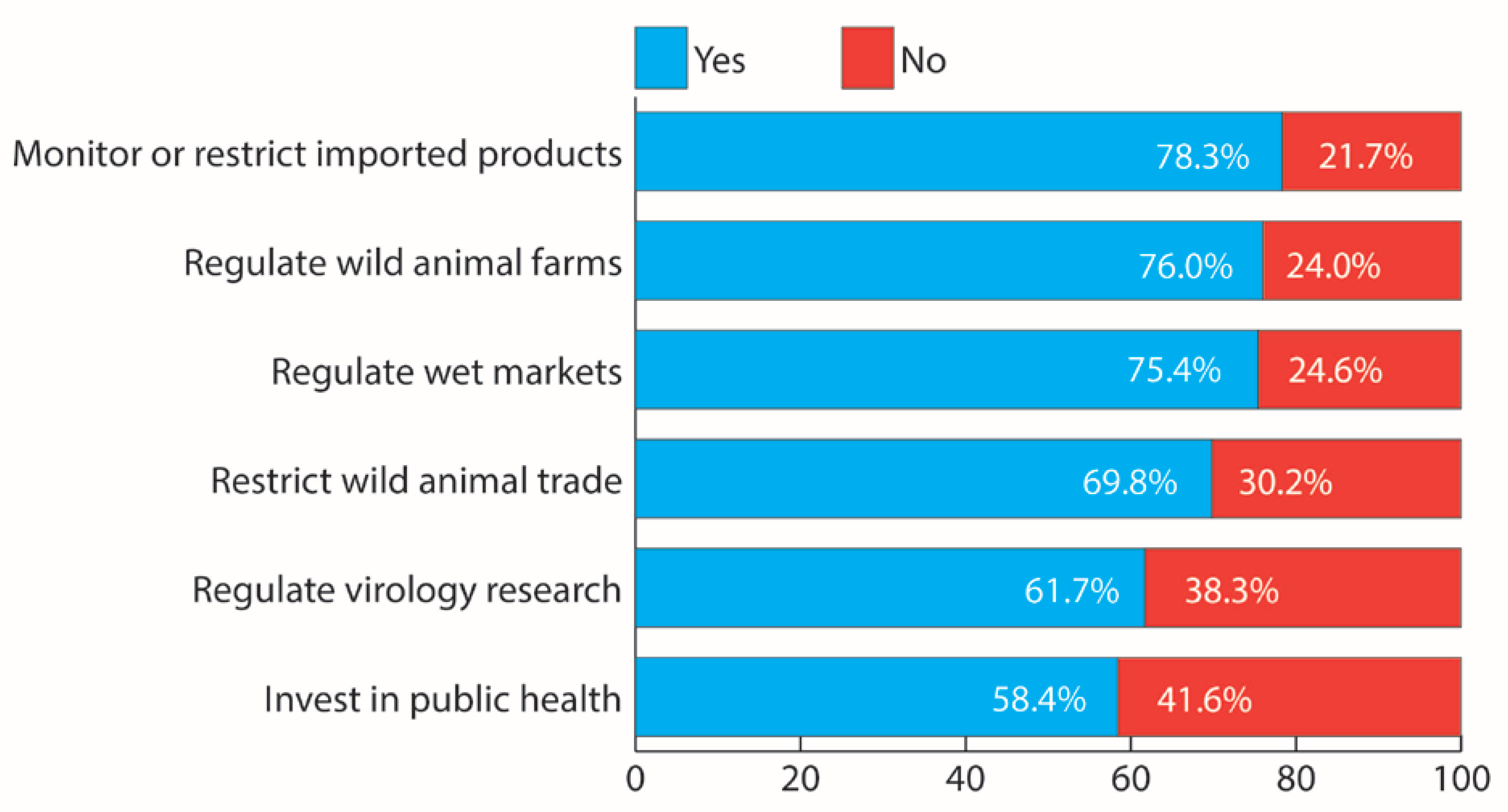

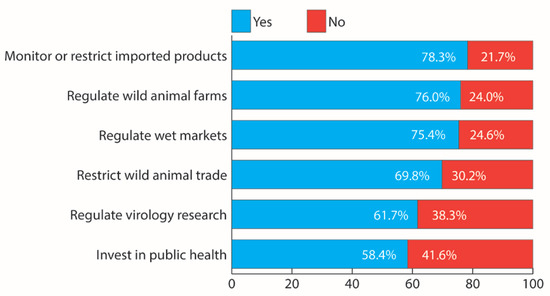

Lastly, the survey asked respondents about measures they thought to be effective in preventing the emergence and spread of infectious diseases such as COVID-19. Again, respondents could select more than one response. The most frequently selected preventative method was monitoring and restricting imported products (78.3%), followed by regulations governing wild animal farms (76.0%), regulations governing wet markets (75.4%), regulations governing the wildlife trade (69.8%), and regulating virology research (61.7%) (Figure 3). Surprisingly, the least selected measure was investments in public health, although this was still selected by more than half of respondents (58.4%).

Figure 3.

Effective ways to prevent the emergence of diseases such as COVID-19, according to survey respondents. “Yes” indicates respondents selected the option as an effective prevention method; “No” indicates respondents did not select the option as an effective prevention method.

Overall, these results show that respondents believe COVID-19 first emerged through a diversity of different pathways, either in China or abroad. Although most report the United States as the initial location where the virus first emerged (52.9%), almost as many (47.1%) report another location or that they do not know. There is thus no overwhelming consensus on COVID-19 origins either in terms of where or how the virus first emerged and respondents generally support a diverse range of policy interventions to prevent the emergence of infectious diseases such as COVID-19.

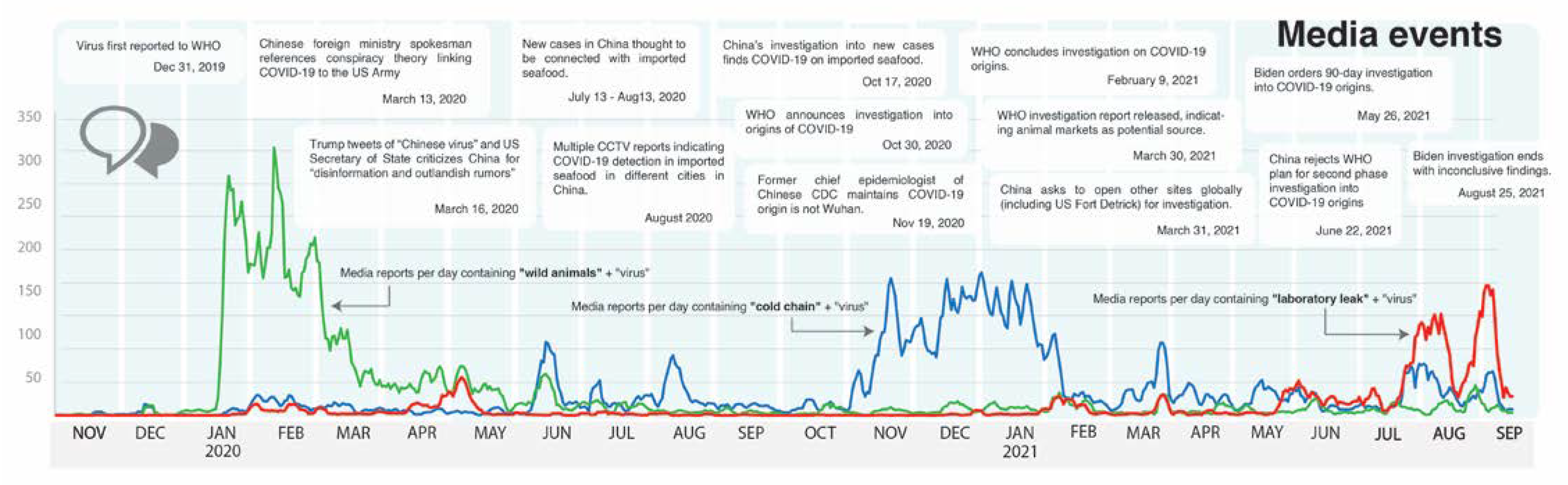

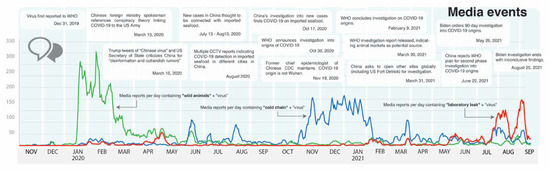

3.2. Media Analysis

Our media analysis provides more context for understanding and interpreting the survey results. The graph at the bottom of Figure 4 demonstrates the frequency of various origin stories in reporting cycles in China since the first detected case in December 2019. The figure illustrates a clear transition from a strong focus on wildlife reporting at the outset of the outbreak to a focus on cold-chain transmission in November 2020 to January 2021, and then transitioning again to a focus on the potential of a lab leak in the summer of 2021.

Figure 4.

Media coverage following the outbreak of COVID-19. Specific media events (top) and number of daily media reports containing the terms “wild animals” + “virus” (green), “cold chain” + “virus” (blue), and “laboratory leak” + “virus” (red) from 1 November 2019 to 10 September 2021.

This trajectory follows certain media events, noted at the top of the figure. Specifically, politicization surrounding the virus began to intensify in March 2020, when US President Trump referred to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus” in a tweet and Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian tweeted that COVID-19 may be linked to the US Army’s participation in the Military World Games held in Wuhan in October 2019 [32]. In the same month, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo shared a heated phone call with a top Chinese diplomat, Yang Jiechi, in which Pompeo criticized Yang for spreading “disinformation and outlandish rumors.” Yang countered that the United States has denigrated China and “aroused the strong indignation of the Chinese people” [33]. Then, in April 2020, for the first time ever, a US state (Missouri) sued the Chinese government over economic losses tied to COVID-19 [34]. With this, the virus became associated with a rise in prejudice and xenophobia [35].

This initial series of political provocations was followed by a number of reports of COVID-19 entering China via frozen imported meats and the head of the Chinese Center for Disease Control, Gao Fu, publicly asserting that COVID-19 existed “long before” it was found in Wuhan [36]. Reports of COVID-19 potentially being present in Europe as early as November 2019 further muddied the waters and fueled hypotheses that the virus first originated outside of Chinese borders [9,37]. Meanwhile, the Biden Administration’s May 26 order for a 90-day intelligence inquiry into the virus origins (including the potential that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was the site of initial human transmission) shifted attention toward the lab leak hypothesis, contributing to a tense political atmosphere. As the investigation concluded in August 2021, yielding no definitive evidence except confirmation that the virus was not “weaponized” and unlikely to be engineered [13], political tensions between the United States and China were at an all-time high.

4. Discussion

These results are quite different from what one would expect regarding perceptions of COVID-19 origins in Western countries. For example, a June 2021 Economist/YouGov poll reported that 58% of 1500 US respondents believe COVID-19 originated from a laboratory in China, with no mention of any other country as a potential origin [38]. In general, conspiracy theories concerning COVID-19 in the United States are prevalent and associated with media exposure [22,39]. Beyond conspiracies, however, most Westerners would nonetheless still likely report China as the origin country—whatever the source—in sharp contrast to our findings for Chinese respondents as reported in Figure 1.

To be clear, what our survey shows—as well as those conducted in the United States and other countries—is perceptions of COVID-19 origins, not any factual information concerning the virus’s true origins. Yet, these perceptions matter in affecting the policy reforms and behavior change needed to prevent pandemics [40,41,42]. They represent the opinions of large swaths of the global population that cannot simply be cast aside. Rather than ignoring these starkly divergent perspectives or dismissing them due to large-scale censorship, policymakers alongside the general public should consider its significance for global pandemic prevention moving forward.

One may be inclined to explain Chinese perceptions in COVID-19 origins and their clear difference from perceptions in Western countries with the acknowledgement that, relative to most Western countries, China engages in censorship and political propaganda at a vast and systematic scale. Why then should we be surprised that Chinese citizens think differently than those in, for example, the United States? However, such censorship does not fully explain the tremendous discrepancy at hand. Looking at COVID-19 origin hypotheses within the United States alone, and the great disparity in how virus origins have been publicly understood and presented in US media, doubts arise over whether Chinese censorship is the only variable at play.

In the United States, perhaps the most illustrative example of the politics of COVID-19 origin stories is the shift in public opinion concerning the lab leak hypothesis in the summer of 2021 [13]. Throughout 2020, this explanation was a fringe theory, banned (some would say “censored”) from Facebook. Then, in mid-2021, with no overwhelming change in evidence, there was a sudden deluge of media reports on the topic, and the Facebook ban was lifted [43]. President Joe Biden ordered the intelligence investigation into the possibility, which concluded with no definitive evidence [44]. What was once marginal then became deemed plausible and worthy of serious consideration by Western accounts. For some, it had become equally likely as the zoonotic transmission explanation or even, according to a vocal minority, significantly more likely [45].

One explanation for this change in US public opinion may be the simple fact that the lab leak hypothesis was initially deeply associated with former President Donald Trump and some of his most extreme followers. Repulsed by Trump’s brand of political extremism, scientists, the media, and much of the general public instead dismissed the hypothesis. With the transition to the Biden administration and the silencing of Trump on social media, however, this strain of inquiry was then subject to new political narratives. The distrust of experts and official accounts, shared by both the left and the right in the United States, resurfaced, at least to a certain extent, in the form of the increased interest in the lab leak hypothesis. This led to Biden’s intelligence investigation and continued media attention, despite many scientists favoring the zoonotic origins explanation (that COVID-19 originated from non-human animals) [46,47].

The rapid turnaround in United States public opinion when it comes to the lab leak hypothesis does not imply that Americans finally embraced a clear-eyed view of COVID-19 origins, whereas before it was distorted. The implication, rather, is that in the face of such extreme uncertainty other social and political factors begin to motivate the virus’s origin stories more than concrete evidence.

The same dynamic holds true in China. Well before the lab leak hypothesis began gaining traction in the United States, the “cold chain” hypothesis was exploding in China. This hypothesis remains largely obscure in Europe and the United States, yet has gained some credence since the WHO investigation findings indicated that it should not be ruled out [10]. The hypothesis has obvious political appeal in China, potentially relieving the entire country from “blame” (not that we should be thinking of COVID-19 origins in this way, but too often that is the rhetoric). Readers outside of China might scoff at the possibility, viewing it as motivated purely by politics rather than evidence, but the reaction has not been the same in China. As our results show, in fact, a large proportion of Chinese citizens maintain that China is not the most likely initial source of the virus and that restricting imported frozen foods is one of the best ways to fight against future pandemics. Paving the way for this thinking, Chinese media selectively reported on speculations that COVID-19 first emerged earlier in other countries (such as Italy and the UK) before emerging in China [48]. This has further induced changes of perception and narratives surrounding virus origination.

China’s particular version of the lab leak hypothesis—in which the virus is said to have originated from Fort Detrick, Maryland and spread via the November 2019 Military World Games in Wuhan—also provides powerful political appeal, raising the possibility that the virus did not originate in China. US Congress did in fact look into the possibility that Wuhan’s Military World Games was a super-spreader event, although not expressly the possibility that the United States was the initial source [49]. China also requested an investigation into US lung injury cases in September 2019, which were connected with e-cigarette usage and may, according to Chinese authorities, relate to COVID-19 [50,51]. At the start of the Beijing Winter Olympics in February 2022, social media declarations of possible renewed attempts at spreading the virus via the games (as was alleged to have occurred at Wuhan’s Military World Games) were on the rise in China, but not covered by official Chinese media.

Despite the lack of definitive proof when it comes to COVID-19 origins, China’s central government is nonetheless pursuing an array of policy reforms to prevent future pandemics (Table 7). These policies include interventions to reform the wildlife trade within the country even though much of popular opinion locates virus origins in the United States. Beyond wildlife reforms, China is also pursuing new sanitation requirements and restrictions on cold-chain imports [52] and new reforms to increase laboratory biosafety in the aftermath of the pandemic [53], including jointly spearheading global biosecurity guidelines, known as the Tianjin Biosecurity Guidelines for Codes of Conduct for Scientists, with Johns Hopkins University.

Table 7.

Major policies established by the Chinese government to prevent the outbreak of future pandemics in various sectors.

Similar reforms need not wait for decisive proof of virus origins in the United States and other countries. Conclusive evidence of a lab leak is not needed to pursue better regulation of “gain-of-function” virology research; reducing the spread of COVID-19 via the cold chain is beneficial regardless of whether the virus emerged inside or outside Chinese borders; and wildlife reforms that China is now aggressively pursuing were long overdue whether or not there was a species jump from bats to humans. Indeed, finding the true origin of COVID-19 does not change the future probability of another virus emerging through these various avenues.

Moreover, changing practices across a variety of domains is possible despite the lack of consensus on virus origins. According to our findings, for example, of those respondents who consumed wildlife on a regular basis before the pandemic (45% of the total sample), the vast majority (89.5%) reported that they were less likely to consume wildlife products after the outbreak. This substantial change in consumption patterns happened despite the widespread belief that the virus originated overseas. On top of this, the vast majority of total respondents indicated support for bans on the sale of bats (85.7%) and pangolins (85.1%) within China, including many who did not report wet markets or animal farms (or even China) as the likely origin of the virus. This shows that practices can be altered and new policies established to mitigate future viral emergence and transmission regardless of definitive proof of origins [54,55].

5. Conclusions

Debates over the origins of COVID-19 are motivated by the laudable goal of preventing future pandemics. For participants on both sides, the ultimate aim is the mitigation of future global health disasters. Is it possible, however, that such heated debates risk exacerbating the problem they aim to solve? Debates over COVID-19 origins exceed the boundaries of our knowledge, spinning out into larger social conflicts over science, the media, and the role of experts, with the unintended consequence that they divide national and international responses to current and future pandemics. Such polemics feed off growing distrust of elites and governmental institutions at home and abroad. They are, in this sense, red herrings: politically explosive and captivating to the public imagination, but liable to exacerbate the mutual distrust and political maneuverings that make responses to pandemics provincial in nature and hamstrung by competing political ideologies and cultural inertia.

How, then, to move forward amid such polarization? Our purpose in recounting these various and conflicting origin stories is not to support or oppose any particular one and not to assert that any are based in fact. Rather, we emphasize that given extreme uncertainty, cultural and political perspectives more than “evidence” (simply because there is such a lack of definitive evidence) begin to impact and sometimes distort public understandings. This is true in countries across the globe.

While it is easy to point to China’s political maneuverings and censorship as the cause of global dissonance, this ignores the dissonance that divides public opinion in many countries, including the United States. In the United States, questioning official narratives as propounded by governmental experts and federal agencies is a national pastime that unites political parties on the left and the right. At its best, such skepticism is a key component of a healthy democracy in which citizens educate themselves and hold their elected representatives accountable. Yet, this skepticism also shapes narratives of COVID-19 origins in the face of inconclusive evidence.

The result, when analyzed at the global level, is the circulation of vastly different narratives of shared global events both within and between countries. Our results show both large-scale discrepancies between origin stories circulating in China compared to what one would expect to find in the United States or Europe, but also finer-grained demographic discrepancies between the uptake of different origin stories within China (low-income households are more likely to support the lab leak hypothesis, for example, while the elderly are less likely to support it). The fact is that our contemporary world is remarkably connected when it comes to the circulation of goods, services, and people, yet starkly divided when it comes to the cultural and political narratives that make meaning of our shared reality.

While previous pandemics—SARS, MERS, Ebola—had clear origins and thus a clear plan of action for prevention efforts, COVID-19 thus far does not. Definitive evidence, however, is not necessary for policy reform and changes in practices now. Pursuing multiple pathways of reform and prevention is preferable to pointing fingers. COVID-19 will not be the last global pandemic. Rather than proffering isolationism, politicization, and ideological polarization, nations must learn from the momentous impacts of the current pandemic and collectively prepare for the next through a plurality of different pathways [56].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.Z., R.C. and J.R.; methodology, A.L.Z., R.C. and J.R.; software, J.R. and X.L.; validation, J.R. and X.L.; formal analysis, A.L.Z., R.C., J.R. and X.L.; investigation, A.L.Z., R.C. and J.R.; resources, R.C.; data curation, J.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.C., J.R. and X.L.; visualization, A.L.Z.; supervision, R.C.; project administration, A.L.Z. and R.C.; funding acquisition R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, grant number [ 2017YFC1503001] and the National Social Science Fund of China, grant number [20ZDA085], and The APC was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Michigan State University’s Institutional Review Board (STUDY00005583).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HEFW1Z.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wenham, C.; Smith, J.; Morgan, R. COVID-19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet 2020, 395, 846–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verschuur, J.; Koks, E.E.; Hall, J.W. Observed impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on global trade. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijaykumar, S.; Jin, Y.; Rogerson, D.; Lu, X.; Sharma, S.; Maughan, A.; Morris, D. How shades of truth and age affect responses to COVID-19 (Mis)information: Randomized survey experiment among WhatsApp users in UK and Brazil. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.; Chiu, C.P.; Zuo, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Hong, Y. Not-so-straightforward links between believing in COVID-19-related conspiracy theories and engaging in disease-preventive behaviours. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworsky, B.N.; Qiaoan, R. The Politics of Blaming: The Narrative Battle between China and the US over COVID-19. J. Chin. Polit. Sci. 2021, 26, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolsen, T.; Palm, R.; Kingsland, J.T. Framing the Origins of COVID-19. Sci. Commun. 2020, 42, 562–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters Staff. Factbox: The Origins of COVID-19. Reuters. 19 January 2021. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-who-china-factbox-idUSKBN29O08P (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Cohen, J. Wuhan Seafood Market May Not Be Source of Novel Virus Spreading Globally. Science. 26 January 2020. Available online: https://www.science.org/news/2020/01/wuhan-seafood-market-may-not-be-source-novel-virus-spreading-globally (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Huang, J.; Cook, G.G.; Xie, Y. Large-scale quantitative evidence of media impact on public opinion toward China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Virus Origin/Origins of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus. 30 March 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/origins-of-the-virus (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Worobey, M.; Levy, J.I.; Serrano, L.M.; Crits-Christoph, A.; Pekar, J.E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Andersen, K.G. The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan was the early epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. Science 2022, 377, abp8715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Liu, W.; Liu, P.; Lei, W.; Jia, Z.; He, X.; Liu, L.-L. Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in the environment and animal samples of the Huanan Seafood Market. Biol. Sci. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxmen, A.; Mallapaty, S. The COVID lab-leak hypothesis: What scientists do and don’t know. Nature 2021, 594, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, G.Y.; Manuel, R. COVID-19 laboratory leak hypothesis: How a few kept the many from considering alternative possibilities. BMJ 2021, 374, n2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Z.L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, J.B. In the Shadow of Biological Warfare: Conspiracy Theories on the Origins of COVID-19 and Enhancing Global Governance of Biosafety as a Matter of Urgency. J. Bioethical Inq. 2020, 17, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, A. The impact of the World Military Games on the COVID-19 pandemic. Irish J. Med. Sci. 2021, 190, 1653–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. Can COVID spread from frozen wildlife? Scientists probe pandemic origins. Nature 2021, 591, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Times. China Requires Disinfection of Imported Cold Chain Food. Global Times. 9 November 2020. Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1206180.shtml (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Fidler, D.P. SARS: Governance and the Globalization of Disease; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- IPBES. Workshop Report on Biodiversity and Pandemics of the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES); IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, K.H. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 263, 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, F.; Awan, T.M.; Syed, J.H.; Kashif, A.; Parveen, M. Sentiments and emotions evoked by news headlines of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya, A.B.; De Lombaerde, P. Regional cooperation is essential to combatting health emergencies in the Global South. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencucha, R.; Bandara, S. Trust, risk, and the challenge of information sharing during a health emergency. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrocal, M.; Kranert, M.; Attolino, P.; Santos, J.A.B.; Santamaria, S.G.; Henaku, N.; Salamurović, A. Constructing collective identities and solidarity in premiers’ early speeches on COVID-19: A global perspective. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.; Mosteller, F. Representative Sampling, I: Non-Scientific Literature. Int. Stat. Rev./Rev. Int. Stat. 1979, 47, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.; Mosteller, F. Representative Sampling, II: Scientific Literature, Excluding Statistics. Int. Stat. Rev./Rev. Int. Stat. 1979, 47, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.; Mosteller, F. Representative Sampling, III: The Current Statistical Literature. Int. Stat. Rev./Rev. Int. Stat. 1979, 47, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolo, J.B. Effects of legalization and wildlife farming on conservation. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 25, e01390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammann, J.; Egolf, A.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Cross-national comparison of the Food Disgust Picture Scale between Switzerland and China using confirmatory factor analysis. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 79, 103756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S. Chinese Spokesman Tweets Claim US Military Brought Virus to Wuhan. South China Morning Post. 13 March 2020. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3075051/chinese-foreign-ministry-spokesman-tweets-claim-us-military (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Elmer, K. Donald Trump Refers to ‘Chinese Virus’ as Washington Asks Beijing to Stop Shifting Blame for COVID-19 to the US. South China Morning Post. 17 March 2020. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3075464/coronavirus-washington-beijing-war-words-continues-chinese (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Wolfe, J. In a First, Missouri Sues China over Coronavirus Economic Losses. Reuters. 21 April 2020. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-china-lawsuit-idUSKCN2232US (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Zeng, G.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z. Prejudice and xenophobia in COVID-19 research manuscripts. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Times. Wuhan’s Huanan Seafood Market a Victim of COVID-19: CDC Director. Global Times. 26 May 2020. Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1189506.shtml (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Albanese, C. COVID-19 Was in Italy in Late November 2019, New Report Shows. Bloomberg. 9 December 2020. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-12-09/covid-19-was-in-italy-in-late-november-2019-new-report-shows (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Jackson, J. Most Americans Now Think COVID Came from Wuhan Lab, New Survey Shows. Newsweek. 2 June 2021. Available online: https://www.newsweek.com/poll-american-covid-lab-1597027 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, K.H. Conspiratorial thinking, selective exposure to conservative media, and response to COVID-19 in the US. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 291, 114480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, J.; Alleaume, C.; Peretti-Watel, P. The French public’s attitudes to a future COVID-19 vaccine: The politicization of a public health issue. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koon, A.D.; Mendenhall, E.; Eich, L.; Adams, A.; Borus, Z.A. A spectrum of (Dis)Belief: Coronavirus frames in a rural midwestern town in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 272, 113743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, M.; Veltri, G.A. Do cognitive styles affect vaccine hesitancy? A dual-process cognitive framework for vaccine hesitancy and the role of risk perceptions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 289, 114403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hern, A. Facebook Lifts Ban on Posts Claiming COVID-19 Was Man-Made. The Guardian. 27 May 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/may/27/facebook-lifts-ban-on-posts-claiming-covid-19-was-man-made (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Nakashima, E.; Abutaleb, Y.; Achenbach, J. Biden Receives Inconclusive Intelligence Report on COVID Origins. Washington Post. 24 August 2021. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/08/24/covid-origins-biden-intelligence-review/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Wade, N. The Origin of COVID: Did People or Nature Open Pandora’s Box at Wuhan—Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The Bulletin. 5 May 2021. Available online: https://thebulletin.org/2021/05/the-origin-of-covid-did-people-or-nature-open-pandoras-box-at-wuhan/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Lytras, S.; Xia, W.; Hughes, J.; Jiang, X.; Robertson, D.L. The animal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2021, 373, 968–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.C.; Goldstein, S.A.; Rasmussen, A.L.; Robertson, D.L.; Crits-Christoph, A.; Wertheim, J.O.; Rambaut, A. The origins of SARS-CoV-2: A critical review. Cell 2021, 184, 4848–4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, X.W. Shi Wei Chong Jian Yidali 2019 Nian Xueyang Geng Duo Yanjiu Faxian Gaixie Xinguan Yiqing Shijian Xian (WHO Re-Examines Italy’s Blood Samples in 2019, More Research Findings Rewrite the Timeline of the COVID-19 Epidemic). CCTV News. 11 June 2021. Available online: http://m.news.cctv.com/2021/06/11/ARTIXDQzQ1ObleoXY0XFCXVy210611.shtml (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Rogin, J. Opinion, Congress is Investigating whether the 2019 Military World Games in Wuhan was a COVID-19 Superspreader event. Washington Post. 23 June 2021. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/06/23/congress-wuhan-military-games-2019-covid/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Global Times. Flu, Vaping or Novel Coronavirus: Experts Suspect the US might have Failed to Identify Causes of Deaths. Global Times. 2 March 2020. Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1181292.shtml (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Fang, D.; Bai Shishi Jiang Daoli. Meiguo da Liugan he Dianzi Yan Beihou de Guiyi Chenmo (Show the Facts and Reason: The Strange Silence behind the U.S. Pandemic and E-Cigarette). Pengpai News. 24 May 2020. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_7544271 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Reuters Staff. China Orders Inspections to Prevent COVID Spread via Cold Chain. Reuters. 3 December 2020. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-china-frozenfood-idUSKBN28D0DY (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Announcement of National Health Commission of China on Enhancing Laboratory Biosafety Monitoring and Management. 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-07/13/content_5526515.htm (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Rizzolo, J.; Zhu, A.L.; Chen, R. Support for wildlife bans and policies in China post COVID-19. Oryx 2023. ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolo, J.; Chen, R.; Zhu, A.L. Attitudes Towards Wildlife Consumption, Health, and Zoonotic Disease in China after the Emergence of COVID-19. EcoHealth. ahead of print.

- Diamond, J. Upheaval: Turning Points for Nations in Crisis; Little, Brown and Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).