Institutional Solidarity in The Netherlands: Examining the Role of Dutch Policies in Women with Migration Backgrounds’ Decisions to Leave a Violent Relationship

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“My husband knew that if I leave [him], I might ruin everything, so he blackmailed me: “if you leave, you will lose your papers, it’s me who decides to send you back to your country”, and I was afraid. Because I was new here, I didn’t know the rules of this country, I was afraid to go to the police and tell them I’m living in hell”—Patience

1.1. Domestic Violence, Culture, Gender, and Migration

1.2. Domestic Violence: An Institutional Perspective on Solidarity

1.2.1. Domestic Violence and Institutional Solidarity

“a pattern of behavior in any relationship that is used to gain or maintain power and control over an intimate partner. Abuse is physical, sexual, economic, or psychological actions or threats of actions that influence another person. This includes any behaviors that frighten, intimidate, terrorize, manipulate, hurt, humiliate, blame, injure, or wound someone”.

1.2.2. Discretionary Freedom and Domestic Violence

1.3. The Dutch Policy on Domestic Violence

1.4. Domestic Violence and Immigration Policies

In Case of Domestic Violence

2. Methodology

2.1. Narrative Interviews

2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.3. Participant Observation

3. Results

3.1. Policies on Domestic Violence in Practice

3.1.1. Women

“I am holding this place for another woman with a family who really needs to leave now instead of tomorrow. But the place is occupied because I am here. Whereas I could have also waited for urgency with my mother”—Yasmina

“When I had to go to the other shelter, they said I need to report first. I said: “I can’t report for my safety”, so they said that I will have to go back to Morocco”—Espoir

“…my father told my mother: “I only accept her dead.” Because the honour of the family, it’s in a sinking ship”.—Patience

3.1.2. Social Workers

“… eventually the perpetrator goes back to the house and the wife and children have to leave anyway. What you often see is that it is very acute, that they must leave at once and leave everything behind. So, a restraining order, it’s good that it’s there. It is for a short period, it can be extended if necessary, but it turns out that it is not enough”.—Sofia

“That fear is valid, though. Because even with the first report, you are not immediately placed in a shelter. There is still research to be done”—Cloë

3.2. Implementation of Policy by Professionals

3.2.1. Women

“People came for my infuse and asked why I was always here alone, where my husband was. “I find it weird, why are you so sick? Are your in-laws good with you?” They asked”—Espoir

“And then the nurse, she called me, and she said: “you must take a step for your children. If you won’t, I will go to child custody, and we will take the children”.”—Mary

3.2.2. Social Workers

“Look, most of the women are here because Veilig Thuis told them: “If you don’t leave that man, we will take your children”.”—Mona

3.3. Leaving a Violent Relationship as a Marriage Migrant

Women

“When I was finally allowed to naturalise for my Dutch citizenship, he [told the IND that they had to] stop my residence permit [suggesting to the IND that the relationship was ending]. So, everything then lapsed. It’s been lost violent years.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Is There Enough Institutional Solidarity towards Women?

4.2. Recommendations

4.3. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The term ‘with a migration background’ was introduced to replace the term allochthonous. The term was widely criticized, including by Schinkel [9]. The term would imprison people, including those, who are born in The Netherlands and hold Dutch nationality, in a perpetual otherness. The new term includes both (marriage) migrants and (Dutch) people of migrant origin, without suggesting that the latter are still considered as migrants, and thus does more justice to their actual status. |

| 2 | Veilig Thuis (Safe at Home) [26] is a country-wide organization with expertise in domestic violence, such as intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and child abuse. Survivors and perpetrators can call Veilig Thuis for help. Moreover, the organization advises professionals when they have concerns or suspicions of violence. Next to listening to, among others, survivors of domestic violence, Veilig Thuis will investigate the severity of the situation. In case of a dangerous and urgent situation, especially when there are children present, Veilig Thuis has to start follow-up steps such as bringing the survivor(s) to a safer situation. |

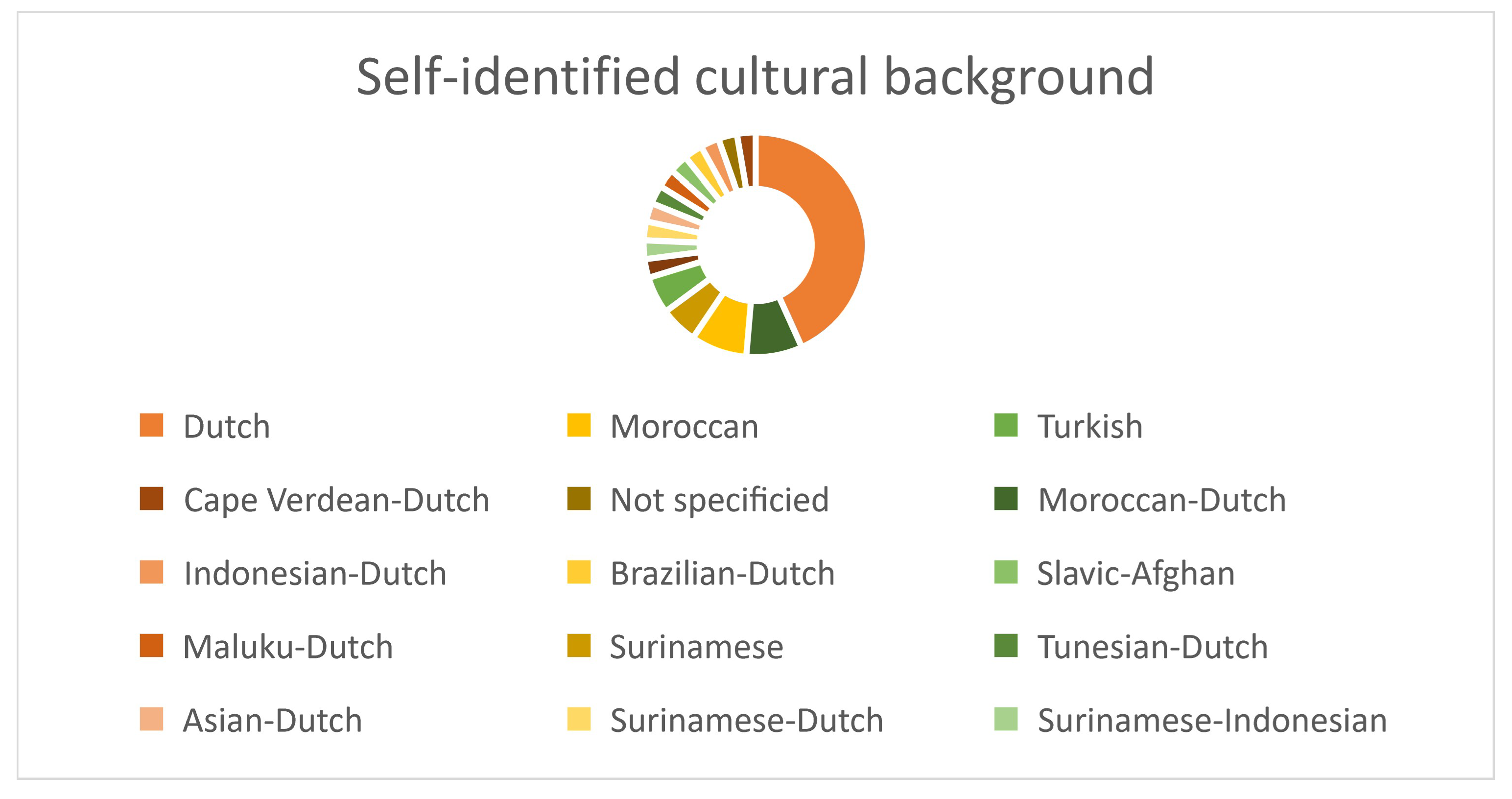

| 3 | We would emphasize that even if the women interviewed here have self-identified the same cultural background, their experiences were far from homogenous, due to the intersections of a range of other factors, including socio-economic status, family structure, and migration histories. Similarly, we recognise that the category of ‘cultural background’, even where self-identified as in this paper, reflects an imperfect categorisation that cannot fully encompass the complexities of individual identity and senses of cultural belonging and hertiage. We use this categorisation here simply as a means to indicate the range of backgrounds of the women we worked with and to foreground their diversity of experience. |

References

- FRA-European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Violence against Women: An EU-Wide Survey: Main Results; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Roggeband, C.M. Over de Grenzen Van de Politiek: Een Vergelijkende Studie Naar de Opkomst en Ontwikkeling Van de Vrouwenbeweging Tegen Seksueel Geweld in Nederland en Spanje; Koninklijke Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Roggeband, C. Shifting policy responses to domestic violence in The Netherlands and Spain (1980–2009). Violence Against Women 2012, 18, 784–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonker, I.E.; Sijbrandij, M.; Wolf, J.R. Toward needs profiles of shelter-based abused women: Latent class approach. Psychol. Women Q. 2012, 36, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, E. He Sees Me as His Possession and Thinks He Can Do What He Wants. Dependent Stay and Partner Violence among Moroccan Marriage Migrant Women in The Netherlands. J. Muslim Minor. Aff. 2021, 41, 522–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, W.; Gelissen, J. Welfare states, solidarity and justice principles: Does the type really matter? Acta Sociol. 2001, 44, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederlands Feminisme en de Strijd Tegen Geweld: Geweld Tegen Vrouwen. Available online: https://atria.nl/nieuws-publicaties/geweld-tegen-vrouwen/nederlands-feminisme-en-de-strijd-tegen-geweld/ (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Methoden: Begrippen: Migratieachtergrond. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/onze-diensten/methoden/begrippen/migratieachtergrond (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- Schinkel, W. Imagined Societies: A Critique of Immigrant Integration in Western Europe; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey, L.A.; Boonzaier, F.; Steinbrenner, S.Y.; Hunter, T. Determinants of intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of prevention and intervention programs. Partn. Abus. 2016, 7, 277–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulhassan, S.; Brumley, K.M. Carrying the burden of a culture: Bargaining with patriarchy and the gendered reputation of Arab American women. J. Fam. Issues 2019, 40, 637–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hart, B.; Verweij, E.; Arbaoui, Y. Heb Geduld: De Betekenis van Het Afhankelijk Verblijfsrecht in Het Dagelijks Leven van Huwelijksmigranten en Hun Partners; Amsterdam Centre for Migration and Refugee Law: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alaggia, R.; Maiter, S.; Jenney, A. In whose words? Struggles and strategies of service providers working with immigrant clients with limited language abilities in the violence against women sector and child protection services. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2017, 22, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur-Prats, A. Family types and intimate partner violence: A historical perspective. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2019, 101, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storer, H.L.; Rodriguez, M.; Franklin, R. “Leaving was a process, not an event”: The lived experience of dating and domestic violence in 140 characters. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP6553–NP6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, A.; Sharma, K. Response and responsibility: Domestic violence and marriage migration in the UK. In Women and Immigration Law; Routledge-Cavendish: London, UK, 2007; pp. 195–215. [Google Scholar]

- Kuskoff, E.; Parsell, C. Striving for gender equality: Representations of gender in “progressive” domestic violence policy. Violence Against Women 2021, 27, 470–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, S.; Powell, A. Domestic Violence: Australian Public Policy; Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2011; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- DeKeseredy, W.S. Bringing feminist sociological analyses of patriarchy back to the forefront of the study of woman abuse. Violence Against Women 2021, 27, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokoloff, N.J.; Dupont, I. Domestic violence at the intersections of race, class, and gender: Challenges and contributions to understanding violence against marginalized women in diverse communities. Violence Against Women 2005, 11, 38–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogat, G.A.; Martinez-Torteya, C.; Levendosky, A.A.; von Eye, A.; Lonstein, J. Intimate partner violence, mental health, and HPA axis functioning. J. Pers. Oriented Res. 2016, 2, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellaard, A.C. Reassembling Violence against Women in Intimate Relationships in The Netherlands: An Ethnographic Analysis of Domestic Violence Policy Assemblages in Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, Radboad University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky, M. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthill, F.; Johnston, L. Home level bureaucracy: Moving beyond the ‘street’ to uncover the ways that place shapes the ways that community public health nurses implement domestic abuse policy. Sociol. Health Illn. 2019, 41, 1426–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veilig Thuis: Hoe Werkt Veilig Thuis? Available online: https://veiligthuis.nl/hoe-werkt-veilig-thuis/ (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Meldcode Huiselijk Geweld en Kindermishandeling. Available online: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/huiselijk-geweld/meldcode (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Allwood, G. Gender-based violence against women in contemporary France: Domestic violence and forced marriage policy since the Istanbul Convention. Mod. Contemp. Fr. 2016, 24, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M. Legal Responses to Domestic Violence; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bargellini, L. Is domestic violence a violation of the right to housing? The Dutch case. Jura Gentium: Riv. Di Filos. Del Dirit. Internazionale E Della Politica Glob. 2021, 18, 134–159. [Google Scholar]

- Alles over Urgentie. Available online: https://suwr.nl/woningzoekende-proces/voor-aanvraag/#kan-ik-urgentie-krijgen (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Voorwaarden. Available online: https://www.urgentie-commissie.nl/voorwaarden (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Urgentieverklaring Voor Woningzoekend. Available online: https://www.regelhulp.nl/onderwerpen/wonen/urgentieverklaring (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Tanha, M.; Beck, C.J.; Figueredo, A.J.; Raghavan, C. Sex differences in intimate partner violence and the use of coercive control as a motivational factor for intimate partner violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2010, 25, 1836–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamberger, L.K.; Larsen, S.E.; Lehrner, A. Coercive control in intimate partner violence. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2017, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterckx, L.; Dagevos, J.; Huijnk, W.; Lisdonk, J.V. Huwelijksmigratie in Nederland; Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wat Zijn de Gevolgen Als ik Niet op Tijd Inburger? Available online: https://www.juridischloket.nl/familie-en-relatie/buitenlandse-partner-of-gezin/te-laat-inburgeren/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Vergaert, E. Responsibility or responsibilization in medical evidencing of domestic violence? The Belgian case analyzed through a care ethical lens. Violence Against Women 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wie Zijn We: Onze Eisen. Available online: https://zelfbeschikkingenverblijfsrecht.nl/ (accessed on 5 August 2023).

| Nationality | Self-Identified Cultural Background | Age | How Long Have They Been Living in The Netherlands? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moroccan | Moroccan | 43 | 2 years and 6 months |

| Moroccan | Moroccan | 27 | 1 year and 6 months |

| Surinamese | Hindu | 46 | 6 years |

| Surinamese | Hindu | 34 | 4 years |

| Iranian | Iranian | 37 | 5 years |

| Pakistani | Pakistani | 27 | 3 years |

| Dutch | Hindu–Dutch | 31 | Since childhood |

| Dutch | Hindu–Dutch | 33 | Born in The Netherlands |

| Dutch | Turkish | 28 | Born in The Netherlands |

| Dutch | Dutch (with Indonesian roots) | 34 | Born in The Netherlands |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roegiers, C.; Saharso, S.; Tonkens, E.; Darling, J. Institutional Solidarity in The Netherlands: Examining the Role of Dutch Policies in Women with Migration Backgrounds’ Decisions to Leave a Violent Relationship. Societies 2023, 13, 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13110243

Roegiers C, Saharso S, Tonkens E, Darling J. Institutional Solidarity in The Netherlands: Examining the Role of Dutch Policies in Women with Migration Backgrounds’ Decisions to Leave a Violent Relationship. Societies. 2023; 13(11):243. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13110243

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoegiers (Mayeux), Chloé, Sawitri Saharso, Evelien Tonkens, and Jonathan Darling. 2023. "Institutional Solidarity in The Netherlands: Examining the Role of Dutch Policies in Women with Migration Backgrounds’ Decisions to Leave a Violent Relationship" Societies 13, no. 11: 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13110243

APA StyleRoegiers, C., Saharso, S., Tonkens, E., & Darling, J. (2023). Institutional Solidarity in The Netherlands: Examining the Role of Dutch Policies in Women with Migration Backgrounds’ Decisions to Leave a Violent Relationship. Societies, 13(11), 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13110243

.jpg)