Abstract

Using data from the General Social Survey, we investigate whether political views increase the risk of social isolation for Black and White Americans. Our findings reveal an increase in conservative political views differently shaping social isolation patterns for Black and White Americans. For instance, changes in political views from liberal to conservative are associated with reduced risk of social isolation for White Americans, whereas a rise in conservative political views is related to increases in social isolation for Black Americans. Results also demonstrate that these patterns remain after accounting for important covariates such as gender, age, education, occupation, marital status, social class, work status, and religion. We discuss the implications of our findings in the context of social relationships, race, and political polarization in the U.S.

1. Introduction

A large and growing body of literature finds that a lack of social connection can have profound social and economic consequences across varied populations [1]. Specifically, socially isolated individuals are unable to participate fully in economic, social, and cultural life and benefit from social connection within a given society [2]. As a result, social isolation can lead to chronic loneliness and boredom, which exerts detrimental effects on individuals’ physical and mental well-being [3]. Moreover, at the population level, widespread social isolation can lead to general dissatisfaction and social unrest. For example, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, global leaders instituted country-wide lockdowns designed to slow the spread of the novel infectious disease. While some countries observed clear declines in COVID infections, hospitalizations, and deaths tied to these mitigation strategies, scholars also noted increases in poor mental health [4]. Mostly recently, the Chinese government reversed its zero COVID policy, mainly due to the rampant social restlessness tied to lockdowns that caused severe social isolation within the general population [5].

We investigate the role of social isolation through the lens of two important social forces: race and racism and political views. Both social forces were pushed to the forefront during the early onset of COVID pandemic in the U.S. First, reported racialized and xenophobic experiences rose to historically unprecedently levels during this time [6], which, according to scholars was mainly fueled by populism, resurgent exclusionary ethno-nationalism, and retreating internationalism. Concurrently, political attitudes also shaped behaviors throughout the COVID pandemic. During the initial stages of the COVID outbreak, U.S. residents reported stark differences in trust of COVID vaccine efficacy and other policy debates related to vaccine uptake. Political differences in trust also spilled over to the 2020 American Presidential election and added to existing ideological divides between liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans that have been undergirding American’s political rifts for decades [7].

In sociology literature on social isolation, one study asked an important question: how do individuals living in our modern society, where opportunities for making connections with others are ubiquitous, become socially isolated [1]? Such a question begs serious examination of social structures that connect people, especially during our time when social media plays critical roles in making those connections. Parigi and Henson’s timely and painstaking analyses of this topic reveals that social isolations entail two aspects: individuals without connections or individuals with connections that carry little meaning [1]. The latter process is the new face of social isolation.

Examining how race and political views shapes social isolation patterning also allows us to better understand how network structures lead to increased social integration. For instance, social homophily is a powerful mechanism that binds people together [8]. Specifically, social homophily is often based on basic ascriptive features such as gender, race, age, or achieved status such as education, occupation, income, and other derived characteristics such as political viewpoints. While similarity breeds connection, dissimilarity threatens relationship building and social networking, inducing social isolation. In sum, we identify we argue that race and political views are critical elements of social homophily that may play a role in social isolation when combined.

In the following section we provide the definition of social isolation and outline the significance of studying social isolation. We then shift our focus attention to the extant literature on social networking processes and the guiding principle (homophily) for interpersonal associations. We review the literature on social isolation, focusing on dissimilarity, which disproportionately affects certain segments of the population, as opposed to the homophily that undergirds interpersonal associations. We then describe differences in political attitudes across racial groups—paying attention to particular to differences between Black and White Americans. Finally, based on these bodies of literature, we outline our hypotheses.

2. What Is Social Isolation and Why Does It Matter?

Social isolation is defined as lack of interactions with others or the wider community [9]. Social isolation can result from objective physical separation from others and/or subjective feeling of a lack of social relations and companionship. In essence, social isolation is lack of social relationships or interpersonal associations. Using peer network data, scholars have expanded our understanding of social isolation into different types. For instance, Nino, Cai, and Ignatow further distinguished social isolation into three types: socially disinterested (those who are named by others as friends), socially avoidant (those who did not name any friends nor do they receive any friendship nominations from others), and actively social isolated (those who did not name any others as friends) [10]. All forms of social isolation are related to risky behaviors such as drunkenness and cigarette usage among adolescents. While social isolation can lead to a variety of risky behaviors, it is also detrimental to mental and physical health. Studies find social isolation is a precursor of depression, anxiety, adjustment disorder, chronic stress or illness, insomnia, suicide, and dementia [4,11].

3. Interpersonal Association and Social Integration

Peer groups and social networks are formed by a process called interpersonal association. People develop relationships through various mechanisms, such as marriages, kinships, workplaces, churches, sport events, hobby clubs, or any other venues that facilitate interpersonal interactions [8]. However, interpersonal associations develop based on one important principle: homophily. Homophily is the tendency to seek out and develop relationships with people who are similar to themselves. This is the concept of “birds of a feather flock together”, meaning that people are naturally attracted to forming bonds with those who share comparable traits [8]. Scholarship has found that the characteristics that often define similarity among individuals are gender, race, age, education, occupation, income, religion, hobbies, and personal opinions such as political viewpoints.

In the U.S., studies find that the social homophily is a main operating principle that shapes American’s interpersonal associations and social interactions. In the 1980s, social networks in the U.S. mostly comprised the same race, mixed genders, similar education, occupations, and age [12]. More than two decades later, in 2004, personal networks’ makeup did not change much, with respect to networks based on race, class, and gender. Interestingly, however, loneliness has increased since the 1980s, with the average size of personal networks decreasing from 2.94 to 2.08, and the mode of core discussion groups changing from 3 in the 1980s to a staggering 0 in 2004 [13].

Much like the social statuses that are classified as achieved (education, income, and prestige) through personal endeavors and ascribed (gender and race) through birth, homophily may also operate based on achieved and ascribed homophily. In particular, the ascribed social status is conducive to interpersonal associations. For example, interpersonal interactions often take place along ascribed social status dimensions as individuals interact with others of the same racial and gender groups. Meanwhile, similarity in achieved social status is also facilitative to interpersonal associations. Often, social interactions based on ascribed and achieved homophily can be mutually reinforcing. For example, White men have significant advantages in the labor market [14], resulting in higher levels of income and wealth, so the strong social connections between White men can be due to both an ascribed (being White and male) and achieved status (higher income and wealth). Conversely, the varied structural disadvantages women and other historically marginalized groups experience in the labor market may result in lower levels of wealth and income, which may also restrict their interpersonal networking due to their ascribed and achieved statuses.

4. Social Isolation: A Result of Interpersonal Disassociation

Opposite social homophily, social heterogeneity and dissimilarity can be a social force to set people apart, producing interpersonal disassociation and social isolation. Social dissimilarity along ascribed statuses such as gender, race, and age render social interactions and relational formations less common for people that hold these varied social positions and brackets. Likewise, social interactions among people with dissimilarities such as education, income, occupation, and even political viewpoints are far less common than among people with similar characteristics in those dimensions. Consequentially, social separation or distancing is a more common occurrence between people across different spectrums of ascribed and achieved status.

Certainly, social heterogeneity and dissimilarity do not affect different segments of the population in the same way. One large national study documented that being unmarried, male, having low education, and low income are all associated with social isolation [15]. Interestingly, the study also reported that older White Americans are more likely to be socially isolated than Black Americans and Hispanics. Findings from this study highlight important mechanisms for individuals to establish connections and social networks with others. In particular, marriage is an important driver of social connection and a key mechanism to avoid social isolation [16]. Income and education may provide opportunities for social connection via schools and workplaces. Gender gaps in social connections between men and women are well documented, with women being more socially connected than men [17]. However, racial disparities in social connections receive mixed results, whereas some report social connections for White people are more than for minorities, especially in the labor market [14]). Others suggest the opposite effects, i.e., racial and ethnic minorities are more closely knit into social networking with each other than with White people [15].

5. Race, Political View, and Social Isolation

While political politization has existed since the founding of the United States, polarization has increased in the last two decades [18] (chapter 8), with political ideologies of liberal and conservative drifting further way, leaving less room for mutual understanding and tolerance. Fundamentally, political party affiliations are often reflective of fundamental attitudes and beliefs about the role of government in social life [19]. With increased hostility of those who are politically different, one’s political views can be enough to make a person unwelcome in a peer group. When groups are already divided by race, a person who does not fit in with the same political views is marginalized, making it difficult to find social connection.

As an individual’s political viewpoints shape their interpersonal associations, isomorphism reinforces the racial divide and political orientation [19]. Conversely, holding political views that do not align with the predominant views of a racial group can be detrimental to relational construction, especially in the current social environment of political polarization. In the U.S., most Black Americans are Democrats [20], holding liberal political views, whereas most White-Americans are Republicans [21], embracing conservative political views. When the two forces operate in tandem, they create strong relational divides, such as Democratic and liberal Black Americans and Republican and conservative White Americans. Those outside the two defined groups, such as Democratic and liberal White Americans and Republican and conservative Black Americans, are truly outsiders and outcasts, finding their political views very foreign within their own respective racial groups.

The impact of holding minority political positions within a racial group can be forceful and direct. Liberal White Americans and conservative Black Americans find themselves at odds with their own racial groups in terms of their political beliefs, whereas, at the same time, they find it hard to traverse outside of their own racial groups to find like-minded others that share the same political viewpoints. The force of isomorphism is compounded with the ascriptive and achieve statuses combined, producing a narrow field for political minorities within each racial group to be social networking with others. Hence, social isolation results from such combined force of racial and political homophily, producing a divergent path between Whites and Black Americans in terms of how political views influences social connections. A general hypothesis is that impact of political views on social isolation is contingent upon a person’s racial group, which results in the following two hypotheses.

H1: the impact of political view on social isolation is significantly different between White and Black Americans. For White Americans, increases in political views from conservative to liberal are associated with increases in social isolation.

H2: the impact of political views on social isolation is significantly different between White and Black Americans. For Black Americans, increases in political views from conservative to liberal are related to decreases in social isolation.

6. Data and Variables

Data were drawn from the General Social Survey (GSS) 2018 [22]. Conducted by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC), the GSS surveyed US respondents regarding their basic social demographic features, economic conditions, and their opinions on a wide variety of social issues. Since its inception, the GSS employed a rotation design, under which some questionnaire items are asked to the whole sample, whereas others are asked to half of the sample. Such design increases the number of questions being asked by rotating some of the originally permanent questions. The GSS 2018 adopted such rotation design option: NORC asked the entire sample (N = 2348) about their basic social demographic features, and economic status variables. However, for some modular variables, such as loneliness measures in our study, the survey only asked about half of the original sample (N = 1175).

Our dependent variable is social isolation, which is measured with three items: How often in the past 4 weeks have you felt that (A) “you lack companionship?”, (B) “you are isolated from others?”, and (C) “you are left out?” Respondents can choose from “never (coded as 1), rarely (coded as 2), sometimes (coded as 3), often (coded as 4), and very often (coded as 5). Due to the social isolation measure being a composite item from three different questions, we tested the Cronbach alpha of the three items, achieving high value of 0.809 [23]. We thus created a social isolation index by adding the three responses and dividing that by 3, producing an index from low social isolation (computed as 1) to very high level of social isolation (computed as 5).

One of our key independent variables is race, in which GSS has been asking respondents to indicate their racial groups based on a long list of 16 racial categories. In our subsample of GSS 2018, the racial breakdown is White (N = 837), Black or African Americans (N = 191), Hispanics (N = 55), and others (N = 70), which includes a wide range of groups of different Asian origins, American Indians, Pacific Islanders, and all others. We also have a number of missing values in the race variable. We determine that because the Hispanic group (N = 55) and the other group (N = 70) are small in number, and also very heterogenous in background compositions, we therefore deleted these two groups, only focusing on the sample with white and black respondents. The listwise deletion procedure of our regression models with a number of independent variables on the social isolation index further reduces the number of cases to 938, which includes 777 White people and 161 Black people. This sample (N = 938) is our sample of analyses.

Other than race, the other key independent variable in our study is political views, measured with a questionnaire item: “we hear a lot of talk these days about liberals and conservatives. I am going to show you a seven-point scale on which the political views that people might hold are arranged from extremely liberal (coded as 1) to extremely conservative (coded as 7). Where would you place yourself on this scale?” In detail, the political views include extremely liberal (1), liberal (2), slightly liberal (3), moderate (4), slightly conservative (5), conservative (6), and extremely conservative (7). Thus, the higher the value in the responses, the more conservative of the respondent’s political views.

7. Findings

To begin, results from our descriptive analysis provide a bit of an optimistic picture with respect to social isolation. Out of the max of 5 in social isolation, the mode, median, and mean for the index are 1, 1.67, and 1.83, respectively, indicating a low level of social isolation in the general population. The quantiles of the social isolation are 1 (25 percentile), 1.67 (50 percentile), and 2.33 (75 percentile). On American’s political views, the basic statistics are 4 (mode), 4 (median), and 4.13 (mean), with a standard deviation of 1.54. American’s political views are mostly middle of the road, congregating around the “moderate” viewpoints, with a slight favor of conservative.

Before testing our hypotheses, we run several bivariate analyses to better understand relationships between race, political views, and social isolation. First, between White and Black respondents, does racial disparity in political views exist? Consistent with prior research, the results reveal that White Americans () are more politically conservative than Black Americans (), and such differences ( are statistically significant (p < 0.05). Second, do White and Black people differ in their social isolation indexes? Our two sample means comparison reveals that Black Americans () are a bit lonelier than is White Americans (), but the racial difference is not statistically significant.

Third, do racial disparities exist between White and Black Americans in terms of how political views affect social isolation? To examine this, we first run the bivariate correlation between political views and social isolation separately for White and Black respondents. The bivariate correlation coefficients of the two variables for White and Black respondents are −0.129 ** (p < 0.01) and 0.18 * (p < 0.05), respectively, providing preliminary evidence that supports our research hypotheses: the relationships between political view and social isolation are different between the two groups. For White Americans, a lower social isolation level is related to more conservative political views of the respondents. Conversely, for Black Americans, greater social isolation is associated with the more conservative political views.

Although bivariate statistical analysis provides some evidences of correlations between race, political views, and social isolation, they do not tease out the spurious effects due to shared covariance between other independent variables and the social isolation. For a more rigorous test on relationships between race, political views, and social isolation, we run several regression models. Model 1 in Table 1 includes all independent variables on the whole sample. Neither race nor political views have any significant relationship with social isolation. In other independent controls, those who are in their 30s and 40s have higher social isolation than those who are in their 70s. Perhaps those in their 30s and 40s are busy with work career and familial duties that interfere with their social networking. Marital status has significant relationship with social isolation: compared with those who never married, married people have lower social isolation, and those who are separated from their partners have higher social isolation. It appears that marriage provides more social networking opportunities to couples in the relationship. However, compared with those who never married, those who are separated are more isolated, even though those who widowed or divorced are not. Such a finding is a bit surprising that begs for more investigations. Perhaps this is related to the timing of the relationship dissolution. Those who are widowed and divorced have already performed things to compensate for the lack of social networking due to marriage dissolution, whereas separated people have not performed anything to address the issue of social networking deficiency.

Table 1.

Unstandardized coefficients of OLS regression of social isolation scale.

Social isolation appears to be related to social classes; compared with the low class, both working class and middle class have lower social isolation, However, the upper class does not have significantly lower social isolation. Although the impact of social class on social isolation is not 100 percent linear, the result shows that social class has significant effect on social isolation that being in the low social class engenders social isolation risks that may hinder their efforts to achieve upward mobility. Religious belief also has an impact on social isolations. Compared with those without any religious belief, those with beliefs other than being Protestant or Catholics have higher social isolation level. This is another surprising finding that begs for more systemic examinations. Religious beliefs should provide believers with some social congregations where social networking takes place. We were expecting non-believers to have higher social isolation than believers do due to lack of social institutions/congregations.

It was noted that Model 1 reveals that neither race nor political view have any significant relationships with the social isolation index. Such a finding is not completely surprising, as our bivariate statistical analyses revealed that the relationship between political views and social isolation is contradictory between white and black. For White people, the change in political view from liberal to conservative is related to reduction in social isolation, whereas, for Black people, such a change is related to increases in social isolation. Thus, mixing White and Black respondents in the whole model overshadows the true statistical relationship, as the two groups experience contractionary effects.

Consequentially, we run separate models for White and for Black samples. Table 2 shows that for the sample of White respondents, the results are very similar to the whole sample, except that the relationship between political view and social isolation appears to be significant in the white sample only. Each unit of increase in political view from liberal to conservative is associated with decreases in the social isolation of White respondents. For the Black sample, such a relationship is reversed, and the change in political view from liberal to conservation is related to the increases in the social isolation for blacks.

Table 2.

The contradictory effects of political views on social isolation between White and Black people.

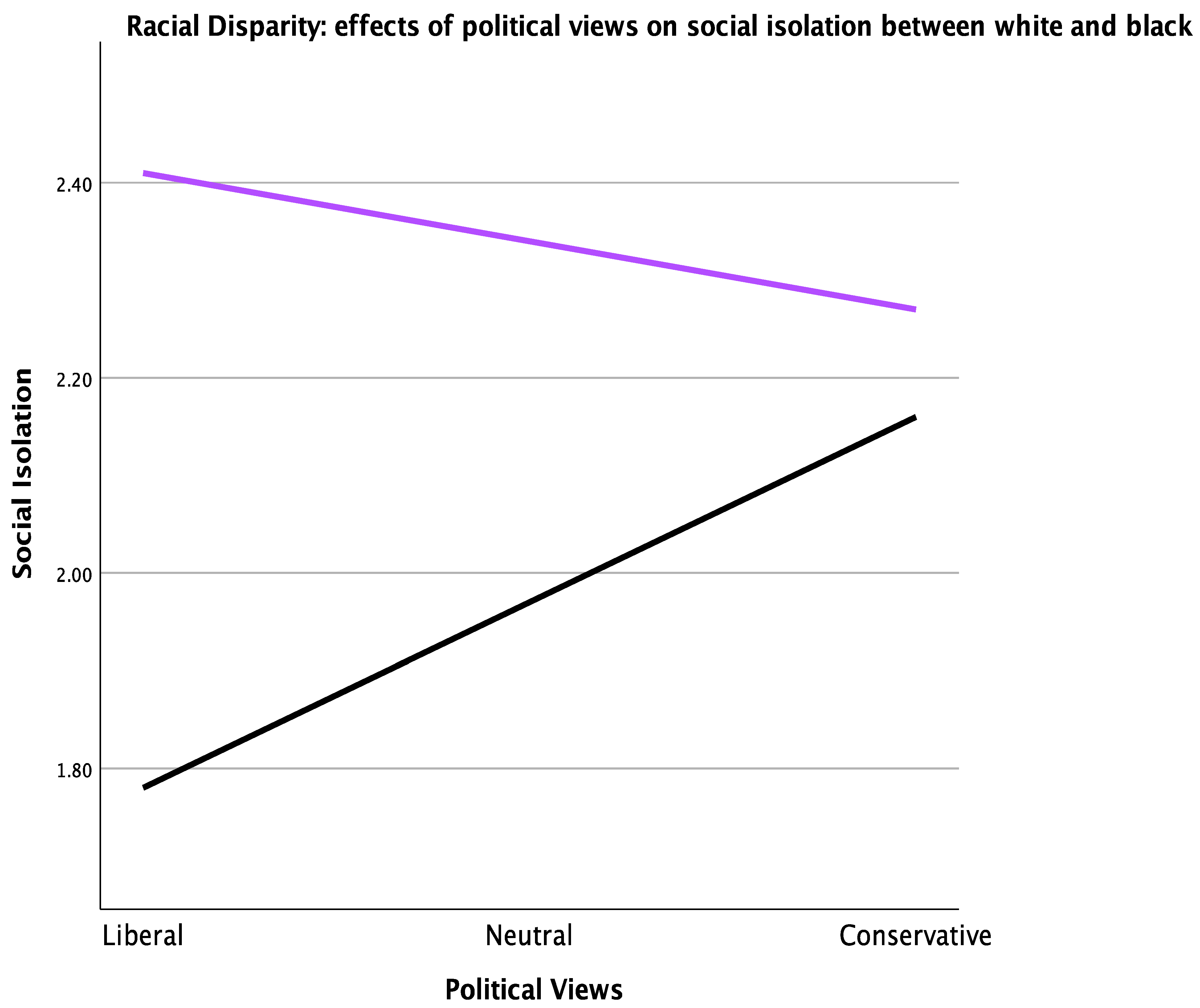

To delve into the details of how the political view has contradictory association with social isolation between white and black respondents, we observe the social isolation of white and black on three levels of political views: liberal (1 st.d. below , neutral (,) and conservative (1 st.d. above ,). Aiken and West suggested that when running interactional effects involving a conditional variable, such conditional variable (in our case is political view) should be controlled at low level at one standard deviation below the mean, intermediate level (the mean value), high level at one standard deviation above the mean [24]. We follow their instructions to observe the main effect of race on social isolation on the three levels of political views. Table 2 displays that at the liberal level in one’s political views, whites have the projected value of 2.41 in social isolation, which is much higher than that of Black people who have the projected value of 1.78. At the neutral level of political view, White people have the projected value of 2.34 in social isolation, which is still higher than that of Black people, who have the projected value of 1.97, but the racial gap in social isolation at this level of neutral political view is much smaller than it is at the liberal level. At the conservative level of political view, White people have the projected value of 2.27 in social isolation, which is still higher than that of Black people who have the projected value of 2.16 but the racial gap diminishes. Statistical examination of the two-sample difference in coefficients in the association between political view and social isolation also reach the significant level. Such results support our two hypotheses that the relationship between political view and social isolation is significantly different between White and Black people. For White people, increases in the political views from conservative to liberal are related to increases in their social isolation. For Black people, increases in the political views from conservative to liberal are associated with decreases in their social isolation.

Figure 1 provides visual illustration of the contradictory effects on social isolation of political views between White (the purple line) and Black (the black line) respondents. While the changes in political views from liberal to conservative relate to the increases in the level of social isolation for Black people, such changes decrease the level of social isolation for White people. The largest racial disparity in social isolation between White and Black respondents materializes when respondents have liberal political views, whereby social isolation for White people is above 2.4, and social isolation for Black people is below 1.8. It is also worth mentioning that at all levels of political views, White people have higher social isolation than do Black people. Future studies should investigate this further, particularly as such result is incongruous with our previous finding that the grand average of social isolation of White people is lower than that of Black people, but the difference is not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Racial disparity in the effects of political views on social isolation.

8. Conclusions

Our study makes an important contribution to the understanding of social isolation by examining individual’s political viewpoint separately between White and Black people. We uncover the contradictory effects of political views on social isolation between White and Black people, and such racial gaps in social isolation are largest when political view is at the liberal level. That is when liberal white finding themselves at odds with the prevalent majority political stance of White people being conservative, whereas liberal Black people fit in their prevailing political view of being liberal among Black people. Consequentially, the social isolation for White people is at its highest, whereas the social isolation for Black people is at its lowest, resulting in the largest racial gap in social isolation.

Our research diverges two-fold results on social isolation and interpersonal associations. First, interpersonal association builds upon homophily, and one of those important binding homophily is political view. Liberal White people and conservative Black people are at odds with their own racial group in terms of prevailing political views, thus experiencing highest social isolation index. Second, our research also discloses that race is an underlying common denominator for American’s interpersonal associations. Liberal White people can easily find many like-minded blacks, and the same goes to conservative Black people. That is not happening per our analyses. Therefore, it is really the two social factors, race and political views, work in tandem to influence individual social networking and isolation.

Social isolation is the polar opposite of social networking, reflecting an extreme form of social exclusion. It is an individual, as well as a societal problem. Socially isolated individuals are unable to participate fully in economic, social, and cultural life that the society in which they live has to offer. A society that is rifted with social isolations may experience great difficulty to integrate, unite, and mobilize its citizens into the broader society. Using the 2018 General Social Survey (GSS), our research reveals that the racial segregation continues to operate as one of the underlying social cleavages. And, the political ideology is emerging to operate in tandem with the long entrenched racial gap to further divide American society.

Social isolation also reflects a lack of social solidarity, resulting from a shortage of mechanical solidarity and the formation of primary ties. Compared with secondary ties, primary social ties provide self-defining utilities and emotional supports [25]. Our study should alert prospective research to investigate other social contexts in inducing social isolations among individuals. Do people living in communities with little racial diversity tend to be socially isolated than do those living in urban areas? How about university/college town as opposed to industry town? While young people rely on social media for many social interactions, older generations may find it hard to adjust to online community for their main socializations. Perhaps the impact of type of town on relationship formation and social isolation is contingent on the age cohort of respondents. In addition, do church congregations produce social isolations for their congregants? For example, while many mainstream churches are welcoming all to join and congregate, some churches are more stringent in terms of beliefs or even financial obligations. As religious attendance has direct impact on social isolation through social integrations and social supports [26], it stands to reason that those churches with high gatekeeping can be responsible for social isolations for many individuals.

With the above findings and discussions, let us take a look at the temporal feature of the data and how future research can continue in this line of work. The year 2018 is unique to our research topics for at least two reasons. First, it is in the middle of Donald Trump’s presidency, which witnesses increasing level of political polarization and intolerant [27]. Political views on immigration, race, and social inclusion became much more conflicting between liberal democrats and conservative republicans. Middle of the road views on controversial issues are giving away to militant and unyielding opinions. Political ideology has been always an important mechanism to divide and separate populations with divergent viewpoints [28]. Under Trump’s administration, it appears that such a political divide has become more potent than it was before. Future research should continue to investigate political ideologies and their influences on social networking and isolation.

Second, the 2018 GSS is before the COVID-19 pandemic, which pushed many controversial social issues to the forefront of American civic life. Along with racial segregation, police and policing, social inequality, and social trust of authorities, institutions, and each other are all controversial topics in today’s Americans’ social life. Our research should inspire a lot more investigations to examine the complex interplay between the different controversial social forces in the post-pandemic American society, focusing on social integration, networking, and isolation. Some urgent research questions are begging for systemic research studies. Is American society more disintegrated and divided in the post-pandemic era? To what extent are American people integrated into civic social life and enjoy their full participation in the civic engagements? Are the social forces responsible for social isolation and societal cleavage becoming more powerful than before the pandemic? We are optimistic that many more studies can reap academic fruits by pursuing those important research topics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y.; methodology, S.Y. and M.N.; software, M.N.; validation, S.Y. and M.N.; formal analysis, S.Y. and M.N.; investigation, S.Y. and M.N.; resources, S.Y. and M.N.; data curation, S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.Y. and M.N.; visualization, M.N.; supervision, S.Y.; project administration, S.Y.; funding acquisition, S.Y. and M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The University of Arkansas Open Access Publishing Fund supported the publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request to the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Parigi, P.; Henson, W., II. Social Isolation in America. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2014, 40, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, E.; Fortune, N.; Llewellyn, G.; Stancliffe, R. Loneliness, social support, social isolation and wellbeing among working age adults with and without disability: Cross-sectional study. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 100965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, T.J.; Rabheru, K.; Peisah, C.; Reichman, W.; Ikeda, M. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 26, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, D.; Rai, M. Social isolation in COVID-19: The impact of loneliness. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Qian, Y.; Jin, Y. Stigma, Perceived Discrimination, and Mental Health during China’s COVID-19 Outbreak: A Mixed-Methods Investigation. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2021, 62, 562–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, A.; Ben, J.; Mansouri, F.; Paradies, Y. Racism and nationalism during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2021, 44, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Chang, H.; Rao, A.; Lerman, K.; Cowan, G.; Ferrara, E. COVID-19 misinformation and the 2020 us presidential election. Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinf. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Cook, J.M. Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Niño, M.D.; Cai, T.; Ignatow, G. Social isolation, drunkenness, and cigarette use among adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2016, 53, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Rev. Public Health 2017, 152, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, P. Core Discussion Networks of Americans. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1987, 52, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Brashears, M.E. Social Isolation in America: Changes in Core Discussion Networks over Two Decades. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 71, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedull, D.S.; Pager, D. Race and Networks in the Job Search Process. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 84, 983–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudjoe, T.K.M.; Roth, D.L.; Szanton, S.L.; Wolff, J.L.; Boyd, C.M.; Thorpe, R.J. The Epidemiology of Social Isolation: National Health and Aging Trends Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. 2020, 75, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrova, O.; Luhmann, M. Social connectedness as a source and consequence of meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 11, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tifferet, S. Gender differences in privacy tendencies on social network sites: A meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Keller, F.B.; Zheng, L. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Examples; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lazer, D.; Rubineau, B.; Chetkovich, C.; Katz, N.; Neblo, M. The Coevolution of Networks and Political Attitudes. Political Commun. 2010, 27, 248–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahler, D.J.; Sood, G. The Parties in Our Heads: Misperceptions about Party Composition and Their Consequences. J. Politics 2018, 80, 964–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, J.E.; Howat, A.J.; Shafranek, R.M.; Busby, E.C. Pigeonholing Partisans: Stereotypes of Party Supporters and Partisan Polarization. Political Behav. 2019, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.W.; Davern, M.; Freese, J.; Morgan, S.L. General Social Surveys, 1972–2018; Principal Investigator, Tom W. Smith; Co-Principal Investigators, Michael Davern, Jeremy Freese, and Stephen L. Morgan; NORC: Chicago, IL. USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Salkind, N. Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics, 1st ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- High, A.C.; Buehler, E.M. Receiving supportive communication from Facebook friends: A model of social ties and supportive communication in social network sites. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 36, 719–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rote, S.; Hill, T.D.; Ellison, C.G. Religious attendance and loneliness in later life. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hout, M.; Maggio, C. Immigration, Race and Political Polarization. Daedalus 2021, 150, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPrete, T.A.; Gelman, A.; McCormick, T.; Teitler, J.; Zheng, T. Segregation in social networks based on acquaintanceship and trust. Am. J. Sociol. 2011, 116, 1234–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).