What if a Bioterrorist Attack Occurs?—A Survey on Citizen Preparedness in Aveiro, Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Data Analysis

3. Results

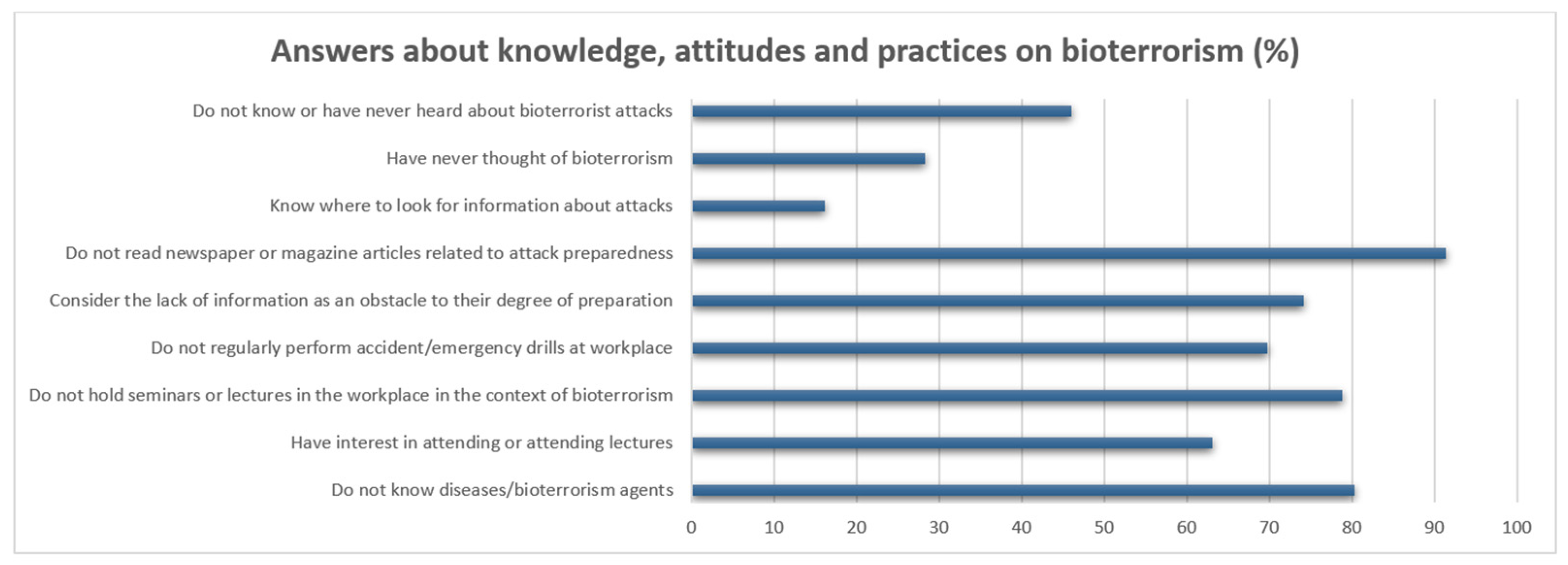

3.1. Knowledge Attitudes and Practices of the Population regarding Bioterrorism

3.2. Knowledge Attitudes and Practices of the Population about Bioterrorism Preparedness

3.3. Level of Importance Attributed to Items in an Emergency Pet Disaster Preparedness Kit

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bioterrorism-Info for Professionals Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website. 2022. Available online: https://emergency.cdc.gov/bioterrorism (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Green, M.S.; LeDuc, J.; Cohen, D.; Franz, D.R. Confronting the threat of bioterrorism: Realities, challenges, and defensive strategies. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, e2–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noah, D.L.; Huebner, K.D.; Darling, R.G.; Waeckerle, J.F. The history and threat of biological warfare and terrorism. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 2002, 20, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacchia, N.A.; Schmitt, K. Medical spending for the 2001 anthrax letter attacks. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 13, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, H.; Breeveld, F.; Stijnis, C.; Grobusch, M. Biological warfare, bioterrorism, and biocrime. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, G.A.; Moran, K.S. Bioterrorism and Threat Assessment. Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission. Paper No. 22. 2004. Available online: http://www.blixassociates.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/No22.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Hoffmann, R.; Raya Muttarak, R. Learn from the Past, Prepare for the Future: Impacts of Education and Experience on Disaster Preparedness in the Philippines and Thailand. World Dev. 2017, 96, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burningham, K.; Fielding, J.; Thrush, D. ‘It’ll never happen to me’: Understanding public awareness of local flood risk. Disasters 2008, 32, 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P. On the role of government in integrated disaster risk governance—Based on practices in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2012, 3, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedin, H.; Samadipour, E.; Salmani, I. Intervention strategies for improvement of disasters risk perception: Family-centered approach. J. Edu. Health Promot. 2019, 8, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.Y.; Koh, C.K. The factors related to bioterrorism preparedness of military nursing officers in armed forces hospital. J. Mil. Nurs. Res. 2015, 33, 6782. [Google Scholar]

- Atakro, C.A.; Addo, S.B.; Aboagye, J.S.; Blay, A.A.; Amoa-Gyarteng, K.G.; Menlah, A.; Garti, I.; Agyare, D.F.; Junior, K.K.; Sarpong, L. Nurses’ and Medical Officers’ Knowledge, Attitude, and Preparedness Toward Potential Bioterrorism Attacks. SAGE Open Nurs. 2019, 5, 2377960819844378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, E. Factors Influencing Preparedness for Bioterrorism among Koreans. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 18, 5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Kim, Y. Factors affecting the competency of nursing students regarding bioterrorism. Iran. J. Public Health 2021, 50, 842843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R. The ABCs of bioterrorism for veterinarians, focusing on Category B and C agents. J. Am. Vet. Med. 2004, 224, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janoutová, J.; Filipčíková, R.; Bílek, K.; Janout, V. Biological agents of bioterrorism-preparedness is vital. Epidemiol. Mikrobiol. Imunol. Cas. Spol. Pro Epidemiol. A Mikrobiol. Ceske Lek. Spol. J.E. Purkyne 2020, 69, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- INE—Plataforma de Divulgação dos Census 2022 Resultados Preliminares. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/scripts/db_censos_2021.html (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Hajian-Tilaki, K. Sample size estimation in epidemiologic studies. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 2, 289–298. [Google Scholar]

- Gershon, R.; Qureshi, K.; Sepkowitz, K.; Gurtman, A.; Galea, S.; Sherman, M. Clinicians’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Concerns Regarding Bioterrorism After a Brief Educational Program. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 46, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokach, A.; Cohen, R.; Shapira, N.; Einav, S.; Mandibura, A.; Bar-Dayan, Y. Preparedness for anthrax attack: The effect of knowledge on the willingness to treat patients. Disasters 2010, 34, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, S.; Pour, S.; Toorchi, M.; Heris, Y. Knowledge and Attitude of Iranian Red Crescent Society Volunteers in Dealing with Bioterrorist attacks. Emergency 2016, 4, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—CDC. Disaster Preparedness for Your Pet. 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/features/petsanddisasters/index.html (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- King, H.; Spritzer, N.; Al-Azzeh, N. Perceived Knowledge, Skills, and Preparedness for Disaster Management Among Military Health Care Personnel. Mil. Med. 2019, 184, e548–e554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Xie, Z. Disaster response knowledge and its social determinants: A cross-sectional study in Beijing, China. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, F.; Gismondo, M.R. Case Study—Italy. In Biopreparedness and Public Health. NATO Science for Peace and Security Series A: Chemistry and Biology; Hunger, I., Radosavljevic, V., Belojevic, G., Rotz, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, R.W.; Lindell, M.K. Preparedness for emergency response: Guidelines for the emergency planning process. Disasters 2003, 27, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifi, B.; Ghanizadeh, G.; Seyedin, H. Disaster Health Literacy of Middle-aged Women. J. Menopausal Med. 2018, 24, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malet, D.; Korbitz, M. Bioterrorism and Local Agency Preparedness: Results from an Experimental Study in Risk Communication. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2015, 12, 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malet, D.; Korbitz, M. Accountability between Experts and the Public in Times of Risk. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2014, 73, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blendon, R.J.; Benson, J.M.; Desroches, C.M.; Weldon, K.J. Using Opinion Surveys to Track the Public’s Response to a Bioterrorist Attack. J. Health Commun. 2003, 8 (Suppl. 1), 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danzig, R.J.; Kleinfeld, R.; Bleek, P.C. After an Attack: Preparing Citizens for Bioterrorism. Center for a New American Security. 2007. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep06393 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Pereira, Z.; Cardoso, L.; Coelho, A.C. Differences in Disaster Preparedness Among Dog and Other Pet Owners in Oporto, Portugal. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 1490–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, M.G.; Bogue, K.; Rohrbaugh, N. Pet Ownership and Evacuation Prior to Hurricane Irene. Animals 2012, 2, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K. Save me, save my dog: Increasing natural disaster preparedness and survival by addressing human-animal relationships. Aust. J. Commun. 2013, 40, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, S.E.; Kass, P.H.; Beck, A.M.; Glickman, L.T. Human and pet-related risk factors for household evacuation failure during a natural disaster. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 153, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C. Strategies for the Improvement of Pet Health and Welfare in Portugal Based on a Pilot Survey on Husbandry, Opinion, and Information Needs. Animals 2020, 10, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.J.; Shin, N.S. Relationship between sociability toward humans and physiological stress in dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2017, 79, 1278–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuma, C.; Poole, K.; Okereke, O.; Fogelberg, K.; Oden, M. Care of Pets in Disasters. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2018, 12, 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Veterinary Medical Association—AVMA Website. 2019. Available online: https://www.avma.org/public/EmergencyCare/Pages/Pets-and-Disasters.aspx (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Crompton, A.; Musinsky, C. How dogs lap: Ingestion and intraoral transport in Canis familiaris. Biol. Lett. 2011, 7, 882–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schipper, L.L.; Vinke, C.M.; Schilder, M.B.H.; Spruijt, B.M. Effect of feeding enrichment toys on the behaviour of kennelled dogs (Canis familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 114, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewison, L.F.; Wright, H.F.; Zulch, H.E.; Ellis, S.L. Short term consequences of preventing visitor access to kennels on noise and the behaviour and physiology of dogs housed in a rescue shelter. Physiol. Behav. 2014, 133, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, S.L. Environmental Enrichment: Practical Strategies for Improving Feline Welfare. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, J.L.; Croney, C.C. Environmental Aspects of Domestic Cat Care and Management: Implications for Cat Welfare. Sci. World J. 2016, 2016, 6296315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemer, S.; Heritier, C.; Windschnurer, I.; Pratsch, L.; Arhant, C.; Affenzeller, N. A Review on Mitigating Fear and Aggression in Dogs and Cats in a Veterinary Setting. Animals 2021, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliarone, A.C.; Sforcin, J.M. Stress: Review about the effects on the immune system. Biosaúde 2009, 11, 57–90. [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi, S.; Pamei, G.; Solanki, H.K.; Kaur, A.; Bhatt, M. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of first aid among the commercial drivers in the Kumaon region of India. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 1994–1998. [Google Scholar]

- SI Restoration. Professional Urine or Feces Clean up. In Biohazard; SI Restoration Baltimore: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.si-restoration.com/resources/biohazard/pet-urine-and-feces-cleanup (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Oshiro, K.; Tanioka, Y.; Schweizer, J.; Zafren, K.; Brugger, H.; Paal, P. Prevention of Hypothermia in the Aftermath of Natural Disasters in Areas at Risk of Avalanches, Earthquakes, Tsunamis and Floods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, A.K.; Mills, Z.G.; Hu, D. Wet mammals shake at tuned frequencies to dry. J. R. Soc. Interfac. 2012, 9, 3208–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevorrow, N. Helping cats cope with stress m veterinary practice. Vet. Nurs. J. 2014, 28, 327–329. [Google Scholar]

- Kry, K.; Casey, R. The effect of hiding enrichment on stress levels and behaviour of domestic cats (Felis sylvestris catus) in a shelter setting and the implications for adoption potential. Anim. Welf. 2007, 6, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, S.E.; Voeks, S.K.; Glickman, L.T. Epidemiologic features of pet evacuation failure in a rapid-onset disaster. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001, 218, 1898–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, S.E.; Linnabary, R.D. Challenges of Managing Animals in Disasters in the U.S. Animals 2015, 5, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinkea, C.; Godijn, L.; Leij, W. Will a hiding box provide stress reduction for shelter cats? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 160, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomel, B.B.; Marano, N. Essential veterinary education in emerging infections, modes of introduction of exotic animals, zoonotic diseases, bioterrorism, implications for human and animal health and disease manifestation. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2009, 28, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goniewicz, K.; Osiak, B.; Pawłowski, W.; Czerski, R.; Burkle, F.; Lasota, D.; Goniewicz, M. Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response in Poland: Prevention, Surveillance, and Mitigation Planning. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 15, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, H.; Pinto, M.d.L.; Cardoso, L.; Rodrigues, I.; Coelho, A.C. What if a Bioterrorist Attack Occurs?—A Survey on Citizen Preparedness in Aveiro, Portugal. Societies 2023, 13, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13010018

Santos H, Pinto MdL, Cardoso L, Rodrigues I, Coelho AC. What if a Bioterrorist Attack Occurs?—A Survey on Citizen Preparedness in Aveiro, Portugal. Societies. 2023; 13(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Helena, Maria de Lurdes Pinto, Luís Cardoso, Isilda Rodrigues, and Ana Cláudia Coelho. 2023. "What if a Bioterrorist Attack Occurs?—A Survey on Citizen Preparedness in Aveiro, Portugal" Societies 13, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13010018

APA StyleSantos, H., Pinto, M. d. L., Cardoso, L., Rodrigues, I., & Coelho, A. C. (2023). What if a Bioterrorist Attack Occurs?—A Survey on Citizen Preparedness in Aveiro, Portugal. Societies, 13(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13010018