1. The Problem of Identities in Education

As Berger and Luckman [

1] argue “identity constitutes, of course, a key element of subjective reality and, as such, is in a dialectical relationship with society” (p.214). Based on this premise, it is key to consider that it is impossible to understand identity or identities without considering the characteristics of the contexts of which they are part and their reconstruction, derived from the social and historical changes that occur.

At a time of global crisis in which the survival of our democracy is in doubt and in which authoritarian and neoliberal discourses are emerging, it is essential to assume that there are “plagues” to be faced for the dignification of life in society, human rights, and social justice [

2]. This situation has accentuated the role we play as citizens in pursuit of solidarity and the common good. However, our increasingly globalized and diverse societies often forget to recognize and care for plurality and diversity, perpetuating what is referred to as “failed citizenship” by invisibilizing or excluding existing minority groups [

3].

Aspiring for change involves reflecting on what kind of citizenship we want to form and how we can build more inclusive spaces and identities. The teaching of Social Sciences can be an instrument of social change, but it is urgent to know what the representation of children and young people about their identities and their disposition in the public space is since the construction of a better future depends on their ways of being and being in the world, on their commitment to democracy and current problems [

4].

Through the study we propose, we intend to explore the social representations of the identities of students of the Primary Education Degree, due to their condition as young people and future teachers. Moreover, we do it from two different contexts: the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and the University of Seville (US).

We use the concept of social representations as a form of social thinking, which helps us to better understand the construction of social reality by people, in the form of images and concepts, based on the dialogue between the individual and the collective [

5,

6]. Furthermore, we use the concept of practical perspectives [

7,

8,

9] to indicate students’ ideas about how they think or how they imagine the educational practice of working on identities in a primary education classroom when they become teachers.

The research problems we intend to answer are:

What social representations do teachers in training have about the construction of their identities, are there differences between the representations of US and UAB students?

What elements do they consider most suitable for working on identities in the Primary Education classroom? Are there any differences between the representations of UAB and US students?

- a.

What are the purposes of working on identities in the classroom?

- b.

What Social Science contents do they select?

- c.

What types of activities do they propose?

What is the relationship between the representations on the construction of their own identity and their practical perspectives on the teaching of identities in primary education? Are there differences between the two groups?

2. Identities and Social Sciences Teaching

The crisis resulting from COVID-19 has posed a great challenge in our society, paralyzing the accelerated functioning of our lives, and filling our daily lives with uncertainty. This situation has exacerbated existing inequalities and social injustices, making it difficult for part of the world’s population to access basic resources.

In this context, from the educational field, a debate resurfaces around the urgency of educating global citizens, making them aware of and committed to the situation we live in and, consequently, to the social, economic, and political challenges that arise [

2,

3]. The construction of identities in a global context presents itself as a challenge within the teaching of Social Sciences; how can we favor the construction of inclusive and global identities while maintaining the characteristics linked to our own origin and local territory, and how do the different planes of our identity combine and what impact does it have on the teaching-learning processes?

Studies that have tried to delve into the identity construction of young people show, on the one hand, that their representation and identification vary depending on the context [

10], as well as that participation in real democratic experiences favors individual and collective identity changes [

11]. According to Ross [

12] “citizenship is an important aspect of our identities: it is the aspect that involves our political engagement and participation in the community” (p.136). Within the key concept of “citizenship” Santisteban and Pagès [

13] emphasize considering the concept of identity and otherness as part of its definition:

“The concept of “identity” is first associated with that of “otherness”, i.e., we define ourselves in terms of differences with other people, but also by our origin, our territory, or our beliefs. Identity can be associated with a legal status with the state, which differentiates citizenship and foreignness. It can also be related to representative national symbols”

From this definition, education for citizenship and Social Sciences play a preponderant role, since one of its purposes is to form the social thinking of children and young people [

14,

15], for participation, commitment, and social action [

16,

17]. To face the complex social problems of our world, youth must form critical and creative thinking [

18], i.e., can rationalize information, critically reading reality (causality), understanding beyond the obvious (intentionality) and proposing alternatives and solutions to emerging problems (relativism) [

19,

20].

In the case of teachers in initial training in Social Sciences, there is a great challenge linked to this issue. First, because they must become aware of what their identities are and how the school has favored their construction. Second, because this reflection can and should have an impact on the way of conceiving how these issues should be worked on in the classroom. It is useless to work on a discourse on general goals in initial training if, on a practical level, there is no reflection on the possibility of reconstructing our identity traits and knowing how they condition our ways of being and being in the world.

The study conducted by Tosello [

21] with Social Sciences teachers in different parts of the world, points out how most of the interviewees have a representation of identities of a static and finished character, as opposed to a minority group that understands them as a social construction. To ensure that the formation of social and critical thinking in schools favors the construction of inclusive identities, these must be analyzed and made visible from the initial training of teachers. If we wish to achieve real change in society, we must bet on the training of reflective and critical professionals [

22], focused on the development of “learning to debate, dialogue, social, political and ideological commitment” [

19] p.135. For their part, González-Valencia and Santisteban [

23] in a study of the social representations of teachers in training on political education, conclude that these representations are diverse and are influenced by both the social and educational context. Moreover, as presented in the study, teachers’ representations of political education have an impact on their practical perspectives on their approach in the classroom.

Considering that teachers in training have schemes of thought and action derived from their own experience as students, as well as from their daily experiences [

9], it is relevant to know what their representations of the construction of their identities are, as well as their ideas on the didactic transposition in the classroom. From these accounts, obstacles can be detected in the treatment of identities in school that help us, from initial teacher training, to avoid the development of teaching and learning models of Social Sciences that show a unique and finished reality, and progressively promote alternative didactic models, critical and based on the investigation of controversial issues or relevant social problems [

24,

25,

26,

27]. The goal is to favor the analysis of the identified plurality of problems [

28], to give voice to invisible protagonists [

29] and to become aware of the interaction between local and global problems [

30].

3. Material and Methods

In this research we followed a method based on case studies [

31], to explore the social representations of teachers in initial training in two different realities. Although it is a qualitative study, we have employed mixed methods in the analysis, to save any reductionism in the interpretation of the information and to acquire a more complete view of the research questions we intend to answer.

We now proceed to describe in detail the particularities of the participants in the study, the instrument, and the analysis procedure.

3.1. Participants

The study involved students from two Spanish universities: the University of Seville (US) and the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB). The sample was purposive, and the main selection criterion was that the participants were in their third year, taking the subject Didactics of Social Sciences.

Carrying out the study with these participants allowed us to respond to the research problems due to the double condition that they fulfill as students and future teachers. In addition, having two different contexts also favors the analysis of the information considering the specificity of each environment and the possible comparisons.

In this sense, it is necessary to consider that Seville and Barcelona are two Spanish cities with different particularities. Seville is in the south of Spain and is the capital of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia. Barcelona, on the other hand, is located on the northeast coast of Spain and is the capital of the Autonomous Community of Catalonia. This configuration in Autonomous Communities has not always been so in the Spanish territory. Before the Spanish dictatorship, Catalonia had some autonomy. However, during the Franco dictatorship, the rights of cultural minorities (such as the Catalan language) were repressed by Spanish nationalism. During the Spanish democratic transition, the “State of Autonomies” was reestablished [

32]. This implies that the Autonomous Communities have autonomy from the central government in some areas such as health and education. However, the creation of the autonomies was incomplete, in the sense that central policies were administered without the effective participation of the different autonomies [

32]. Currently, in Catalonia, there are nationalist currents that defend its political independence and the creation of a sovereign state. In the case of Seville and the Autonomous Community of Andalusia there are no such movements.

The students participated in the study on a voluntary basis. The data have been anonymized respecting the code of good practices in research (Agreement of the Governing Council of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, 30 September, 2020, on good practices in research) [

33].

A total of 136 students participated, of which 80 belonged to the US and 56 to the UAB. As can be seen in

Table 1, the ages of the participants are between 20 and 27 years old. Most of the total participants in the study are women, 96 versus 40. In the case of both the US and the UAB there is many students who reside in the metropolitan area of the two provincial capitals, although in the case of Barcelona the number of students who do not reside in the capital is much higher. As for the country of birth, while in the case of the US students indicate Spain, in the case of the UAB there is variability. Some of the respondents indicate Catalonia and in some cases Barcelona as their country of birth.

3.2. Instrument

For data collection, we designed a questionnaire combining closed and open-ended questions (see

Supplementary Material S1). This questionnaire has been designed considering previous instruments and studies [

34,

35]. The questionnaire is reflexive in nature and consists of four parts.

Table 2 lists the instrument sections and questions considered for this study. First, it contains a personal data section referring to sociodemographic questions.

Section 1 contains questions related to the construction of identities and their representation.

Section 2 and

Section 3 are related to practical perspectives on working with identities in the classroom. The last section contains some open questions for reflection. It is noteworthy that to favor the identification of the respondents with different elements related to their identity we considered it necessary to select images linked to their close context. For this reason,

Section 2 of the instrument is different and specific for each of the contexts. In

Supplementary Material 1 can be seen: 2.5.A. for the Andalusian context and 2.5.B for the Catalonian context.

The instrument is linked to the research problems presented above. Through

Section 1 and

Section 4 of the instrument, it has been possible to explore the representations of teachers in training on the construction of their identities (research problem 1). Through

Section 2 and

Section 3, the practical perspectives on the teaching of identities in the classroom have been observed (research problem 2). The interaction between both pieces of information has allowed us to understand the relationship between the construction of their identities and their practical perspectives (research problem 3).

The instrument has been validated by an expert judgment, based on criteria of clarity and relevance of the questions. In addition, a pilot test was carried out with five active teachers of early childhood education and primary education to determine whether the instrument was able to respond to the research problems and whether the questions were clearly understood.

3.3. Analysis Procedures

The analysis strategy is mixed. For the quantitative analysis, using the SPSS v.26 program, we used descriptive and frequency analysis. In addition, to determine whether the mean differences between the responses of the two groups were statistically significant, we applied the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test, after verifying the non-normal distribution of the data by means of the K-S test (

p > 0.01). To calculate the effect size of the differences, we calculated Cohen’s d, considering low differences to values around 0.2, medium differences to values close to 0.5 and high differences to values above 0.8 [

36].

To deepen the information, we have developed a qualitative analysis of the data, using the Atlas.ti v.8 program. We used an inductive content analysis technique with emerging categories [

37]. The procedure had a first phase, textual in nature, to select Significant Information Units (SIU) linked to two major categories: (1) representations of the construction of one’s own identities; (2) practical perspectives on the teaching of identities in the primary school classroom. The second phase of a contextual nature allowed us to generalize the data to understand the trends described in both categories and groups, in terms of frequency of occurrence.

4. Results

4.1. How They Construct Their Identities

As shown in

Table 3, students rated different elements to explain their own identity on a scale of 1 to 9, where 1 means not at all important and 9 means very important. In the case of the US, the average of the responses considers, in order of relevance, the elements linked to social (m = 7.80), local (m = 7.21), territorial (m = 6.65) and linguistic (m = 6.47) aspects. At the UAB, the same elements, with slight differences, are indicated as the most relevant to explain their identity: social (m = 6.79), linguistic (m = 6.46) and local (m = 6.04).

The mean differences in the responses (

Table 4) indicate that, even though the students select the same elements as most relevant to explain their identity, the differences are significant (

p < 0.05) in the case of the local, national, social, and territorial elements. The largest differences between the groups are in the territory element with a high effect size (d = 0.94). The rest of the elements (local, national, and social) have a medium effect size (d > 0.5).

In addition, from the qualitative data, three typologies have emerged in relation to the construction of their identities: individualistic, mixed, and dynamic.

Table 5 and

Table 6 contain the emerging description of these perspectives and examples of allusion.

The results of this analysis, shown in

Figure 1, reflect that the most frequent typology in both contexts is the mixed typology, which combines individual traits with social aspects of the local and nearby environment (family, friends, town, or city). As can be seen, the least frequent perspective is the dynamic typology, both in the US (11.3%) and in the UAB (9.3%).

4.2. How They Think Identities Should Be Taught in the Elementary Classroom

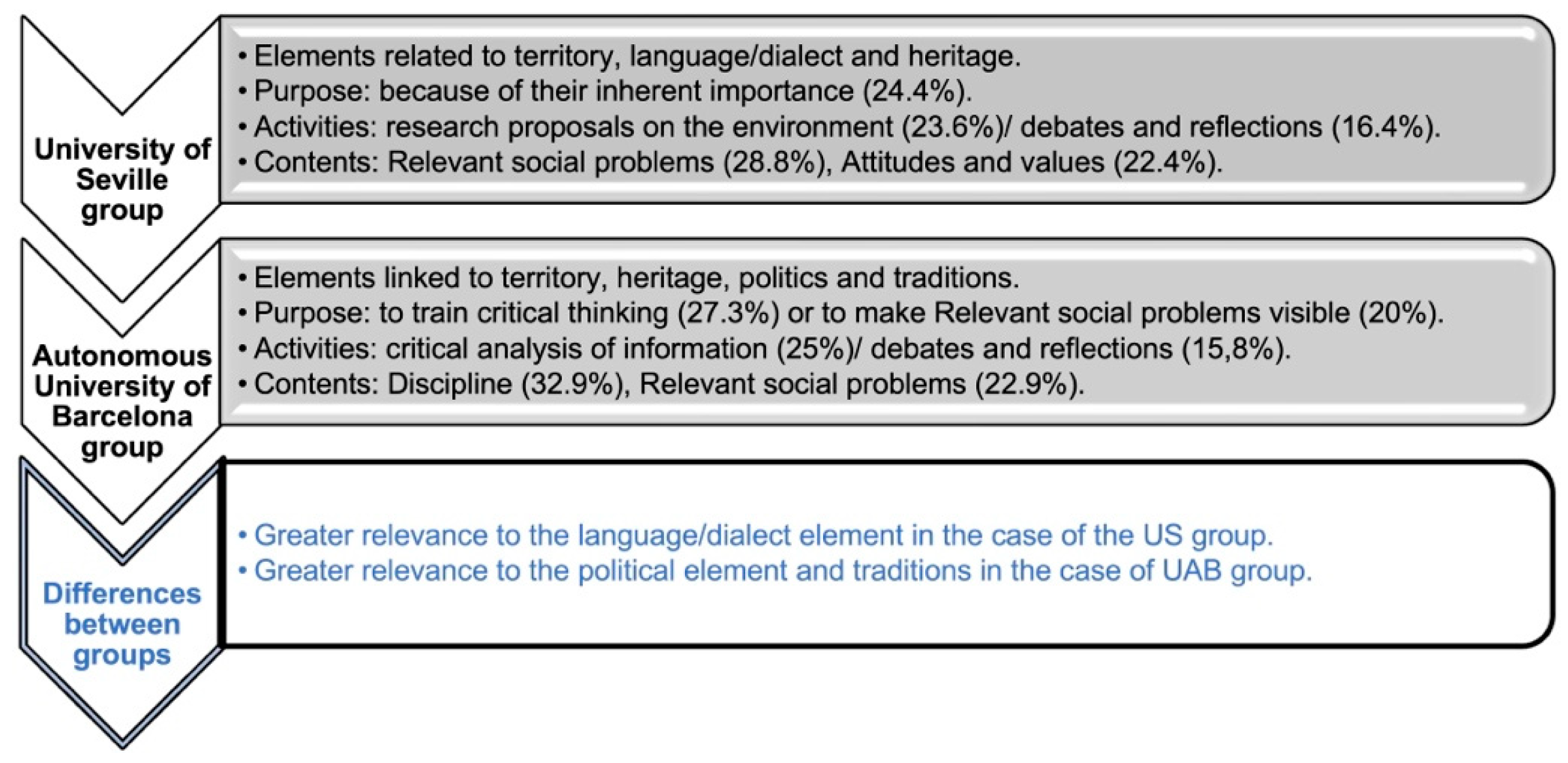

Regarding the elements selected to work on identities in the classroom (

Table 7), the US students indicate as most suitable, on a scale of 1 to 8, where 1 means not at all important and 8 means very important, Territory (m = 5.96), Language (m = 5.94) and Heritage (m = 5.70) and in the case of the UAB, Territory (m = 5.39), Heritage (m = 5.02), Politics (m = 4.99) and Traditions (m = 4.95).

As for the mean differences in the responses, as shown in

Table 8, they are significant (

p < 0.05) for the items linked to Politics, Art, Heritage, and Language/Dialect. In relation to the elements Politics and Language/Dialect the differences are significant with a large effect size (d > 0.8). The elements Art (d = 0.47) and Heritage (d = 0.41) show differences with an effect size close to medium (d = 0.5).

The analysis of the qualitative data has allowed us to know in depth their representations on the practical perspectives of the approach to identities in the classroom, beyond the elements they consider relevant.

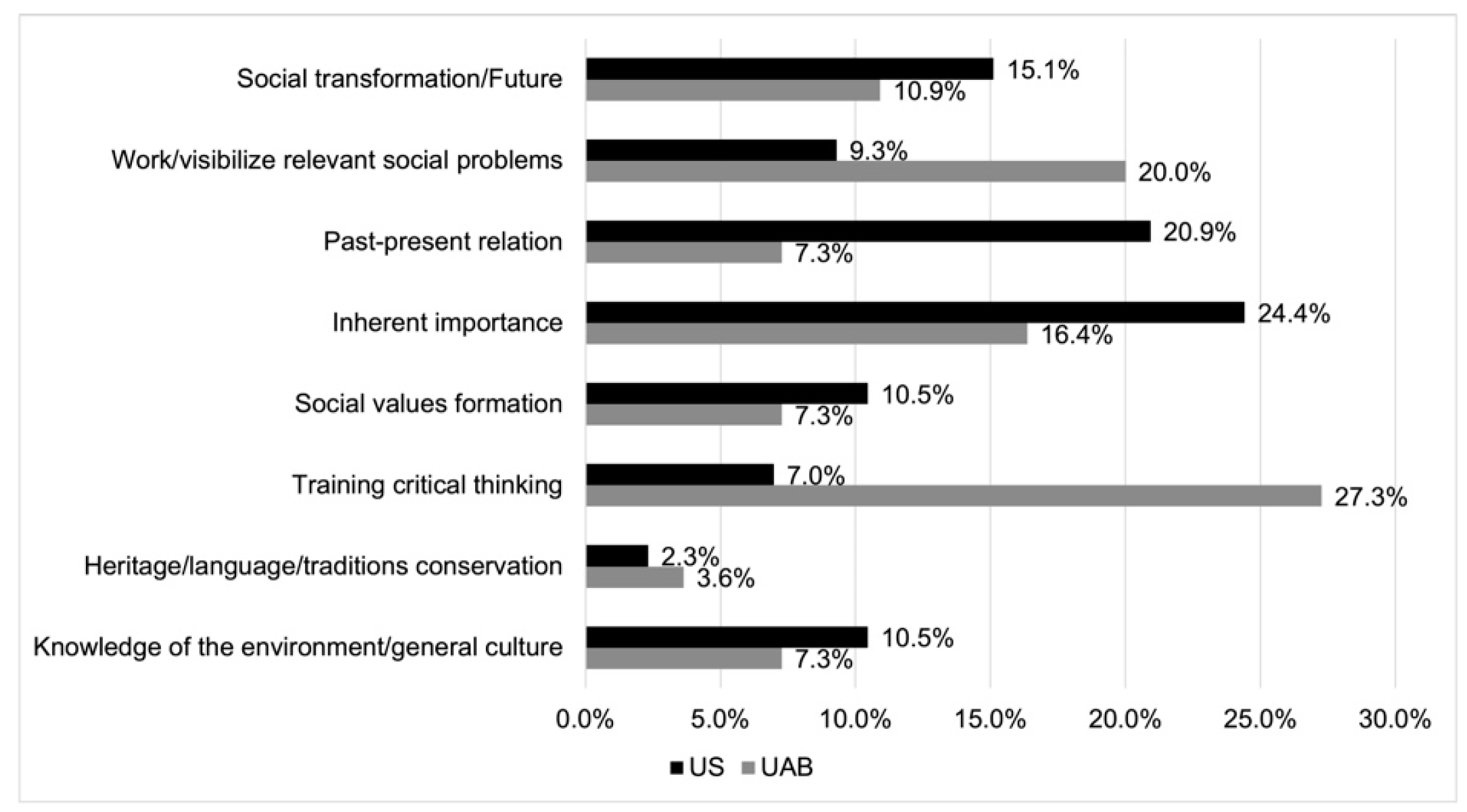

Regarding the purposes that are raised to work on identities in the classroom, as detailed in

Figure 2, in the case of the US the most frequent purpose is its inherent importance (24.4%) without giving argued reasons why it is relevant to work on this issue “it is of great importance to work on this subject since with it we will manage to develop the identity of the students and promote the Andalusian culture” (US_36: 6), followed by the need to understand the relationship between the past and the present (20.9%) “an important part of our identity is our roots, the environment where we live, our people. Therefore, I think it is essential that they know where we come from and what has been the history before us” (US_3:6).

At the UAB, however, the most frequent goals are to train critical thinking (27.3%) of the students “they must be trained as critical citizens so that they can participate actively following democratic values taking into account ethical principles. They should be able to identify what policies or actions to defend for the improvement of societies and their participation” (UAB_112:4) and to make visible or work on relevant social problems (20.0%) “is a relevant social problem and knowing diverse identities and the problems they have caused and still cause is important for them to be empathetic and respectful people who can form their own identity” (UAB_117:6).

As for the contents, as shown in

Figure 3, UAB students propose contents linked to the discipline (32.9%) “some war, such as the Second World War” (UAB_94:3) or working with relevant social problems (22.9%) “globalization, contact with other cultures, massification, exploitation of underdeveloped countries, slavery” (UAB_133:4).

US students propose working with relevant social problems (28.8%) “we could learn what personal identity is, cultural/historical problems, division in society, unequal society, promoting respect towards poor people, equality between social classes, discrimination between races...” (US_46:5) or attitudinal contents or values (22.4%) “mainly values such as respect, empathy, tolerance, etc., referred to attitudinal contents would be worked on” (US_15:5).

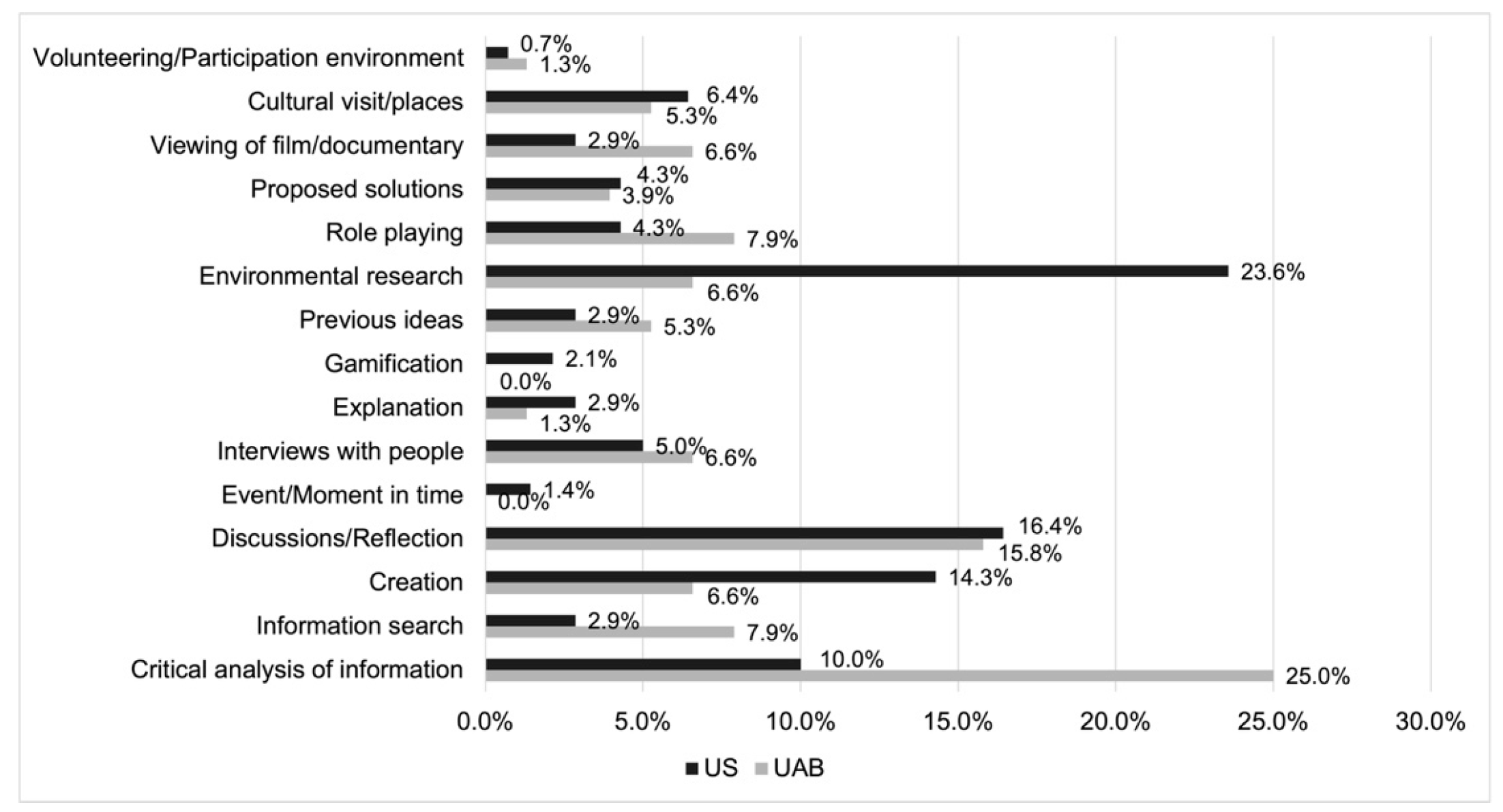

As for the type of activities they propose, as shown in

Figure 4, US students opt for proposing research activities about the environment (23.6%) “a group research on what happened previously in the locality, so that students know the history and different curiosities such as monuments or emblematic places of their locality” (US_3:4), followed by discussion or reflection activities (16.4%) “I would make groups of several people who choose a local festival or tradition and explain to the others what it is about and all its information. After being exposed, I would open a common debate, where students should open personally about what they think about them” (US_22:4).

In the case of UAB the most frequent is to propose activities of critical analysis of information (25.0%) “work from the analysis of news, search for information in different sources, chronology, maps, debate and argumentation, etc.” (UAB_131:4) or debates/reflections (15.8%) “debates: create two groups (without identification of ideology by the students, but it would be developed randomly), and one group should go in favor of Francoism and its ideology, and the other group against.” (UAB_96:4). In both cases, it is less frequent to propose activities that imply solution proposals, either for the research developed or for the critical analysis used, or for the exploration of the children’s previous ideas or representations.

4.3. Coherence between the Representation of Their Identities and Their Practical Perspectives

The trends described above generally show few differences between the groups studied.

With respect to the construction of their identities, a mixed tendency predominates in both groups, in the interaction of the individual and the social, with greater importance on the social, local, and linguistic aspects to explain the construction of their identities.

The differences between the groups are significantly observed in the territorial aspect, to which US students attach greater importance than UAB students. In both groups, less relevance is given to historical and national elements to explain their identity. The aspect they consider less relevant to explain the construction of their identities is the transnational aspect (

Figure 5).

In relation to practical perspectives, in the case of the US, students select elements linked to territory, language/dialect and heritage to work on identities in the classroom. In the case of the UAB, the elements linked to territory, heritage, politics, and traditions are prioritized. The differences are significant with respect to the political element, to which UAB students give more relevance, and to the language/dialect element, to which US students give more value (

Figure 6).

Therefore, roughly speaking, in both cases, there is a correspondence between the elements they consider relevant to explain the construction of their identities and those they believe most suitable for working on identities in the classroom. Similarly, there is coherence between the purposes they propose for working on identities in the classroom, the types of content and the type of activities. Although it is true that in the case of the US, more reflection is required on the purposes for addressing this issue in the classroom. In both cases, a relationship is also perceived between the lack of a dynamic perception about the construction of their identities and the practical perspectives they put forward about their work in the classroom. Although they propose working around relevant social problems or the critical analysis of information, the proposals are based on knowing and understanding reality, but they forget the idea of its transformation or participation, whether inside or outside the school.

5. Discussion

The present study shows how students in initial training have representations about the construction of their identities with a mixed tendency, conditioned by the interaction of individual elements with close social elements. There is a resistance to developing a dynamic vision of the construction of their identities, which considers the interaction of multiple factors, as well as the impact of elements that are not close to them in the reconfiguration of their identities.

These results are consistent with those exposed in the study developed by Tosello [

21] with active Social Sciences teachers in which the lack of a dynamic vision regarding their representations on the construction of their identities is also pointed out. The participants in this study give less relevance to the transnational element in defining their identities. In this sense, the results of Sant et al. [

10] with high school students also make visible few indications of young people identifying themselves as global citizens. This is especially relevant to the extent that in recent years the need to develop a global citizenship has been reinforced. Therefore, and relying on the approaches of Pagès [

30], a closer relationship between global citizenship and the teaching of Social Sciences should continue to be strengthened, also from initial teacher training. We agree with Veugelers [

36], (p. 135) that:

“Identity on a national scale receives a lot of attention within educational policy, [although] little attention is paid to it on an international scale, although it is on the rise. The teaching of one’s own national identity [moreover] often does not receive too critical an approach”.

It is therefore essential to move towards a model of “globalization from below” [

38] from initial teacher training, which allows us to combine critical reflection on our identities with the need to develop multiple, critical, and inclusive identities. As Veulegers [

39] rightly argues, a balance must be sought between national and international orientations of education, to strengthen democracy and tolerance at both levels in a critical way. In this sense, taking as a starting point the representations of the identities of teachers in initial training can favor a significant change in them [

9].

In relation to practical perspectives, the research by González-Valencia and Santisteban [

23] shows how teachers’ social representations have an impact on the didactic proposals they put forward. This is consistent with the results of our study. Students show a perception about the construction of their identities that neglect their dynamic character. This is reflected in the didactic proposals, to the extent that they present activities that serve to develop the skills of understanding and comprehending reality, but obviate the development of the skills of action, commitment, and participation, through activities that involve proposals for solutions, participation, or action [

19]. Similarly, the proposals they put forward forget the phase of exploration of previous representations and ideas.

Therefore, it is necessary to reflect in a deeper way from the initial training on these issues to become aware of the relevance of working from the Social Sciences on identities from their dynamic nature, with the aim of transforming our reality.

On the other hand, it is essential to consider the influence of the context on the practical perspectives of teachers in training. In the case of UAB students, unlike those of the US, they consider the political question as relevant to work on identities in the classroom. This could be due to the secessionist process in which Catalonia is immersed [

32], which promotes in students in initial training the awareness of the relevance of politics as a process of participation, deliberation, and decision-making in the lives of children, and in the construction of their identity and future.

Considering the relationship between students’ representations and their practical perspectives, the social problems that surround us must also be presented in the university classroom. Experiencing a critical, coherent, and research-based formative model of relevant social problems will help to favor the analysis and understanding of the problems and their identity elements, promoting their linkage and engagement with reality [

22]. This will be reflected in the approach to identities in the Social Sciences classroom, with the goal of moving towards a more inclusive, democratic and fair school culture, which promotes public engagement and democratic participation in children and young people [

11,

16,

40].

6. Conclusions

Responding to the research problems of this study, in relation to the construction of their identities (P1) appears the need to reflect in the classroom to move towards a dynamic perspective on identities, which allows teachers in initial training to understand that it is not something finished, that it is in constant reconstruction, as well as that there are issues that they feel distant from themselves but that equally have an impact on their identity.

In terms of practical perspectives (P2), there is a clear need to achieve greater coherence in the models that are proposed. This implies giving more relevance to the purpose of working on identities in the classroom to achieve a transformation and improvement of our environment, not only in relation to present change but also to the future.

In this sense, the types of activities proposed, although in both cases they are proposals for critical analysis of information or research of the environment, forget the contact with reality and with the children’s own experiences. Few activities of exploration of previous representations or participation in the school and social environment are presented, which go beyond visits to monuments or emblematic places in towns and cities. This has some correspondence with the proposed goals, which place little emphasis on the transformation of the environment and the future, and which give less relevance to the real participation of students.

Therefore, there is a need to reinforce sequences of investigative and coherent activities, which do not forget the phase of exploration of representations and ideas about the relevant social problems, in which questions linked to their identities and their ways of being and thinking about reality will necessarily appear; activities that allow them to engage with the problem (beyond their critical analysis), as well as proposals for solutions, improvements or transfer to the environment. Therefore, to also form the citizen identity in the school “to participate is learned by participating”.

In relation to the construction of their identities and the practical perspective (P3), although at the didactic level, work is proposed around relevant social problems or research proposals on the environment, when they detail the type of activities, a deeper reflection on why these proposals can favor the development of multiple identities in children is lacking. This makes us think about the need to implement strategies in initial training that allow students to experience first-hand the work on relevant social problems in relation to the reconstruction of their identities. These experiences could have an impact at the individual level by understanding all the factors that affect us as individuals and society and, on the other hand, transposing these experiences into classroom practice, developing the capacity for commitment and action. Therefore, to experience and reflect on relevant social problem sequences to propose complex designs aimed at citizenship education.

The results presented in this study do not pretend to be generalized, as it is a qualitative study, in two specific realities and formative moments. The study has some limitations, such as the methodological weaknesses associated with the instrument itself. Although we consider that the study can serve to implement new training strategies to work on identities in initial teacher training, we are aware that a more in-depth approach to the subject, through interviews or discussion groups, would provide a more complex view of the reality addressed. The study also leads us to ask ourselves new questions: would teachers’ representations be similar in other contexts, and do in-service teachers have a more critical perspective on the approach to identities in the classroom?

In short, the initial training of primary education teachers requires attention to the construction of individual and collective identities of students, through the analysis of their social representations, as a fundamental part of their citizenship training. Furthermore, as the other essential aspect of their training, future teachers must work with their practical perspectives, to transfer to the classroom an inclusive, diverse, and global idea of identity, making all people and groups visible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M.; Data curation, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M.; Formal analysis, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M.; Funding acquisition, N.P.-R.; Investigation, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M.; Methodology, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M.; Project administration, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M.; Resources, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M.; Software, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M.; Supervision, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M.; Validation, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M.; Visualization, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M.; Writing—original draft, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M.; Writing—review and editing, N.P.-R., A.S., N.D.-A.-F. and E.N.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by University of Seville Own Research and Transfer Plan “Short-term stays in Spain and Abroad for the year 2020 for beneficiaries of scholarships/contracts for Pre-doctoral or Personal Research Trainees” grant number VIPPIT-2020-EBRV. It is the result of a short stay carried out by Noelia Pérez-Rodríguez at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available because the identities of some participants are visible, undermining privacy protection. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to N.P-R, nperez4@us.es.

Acknowledgments

The collaboration of the preservice teachers training is gratefully acknowledged, as well as the contributions made by the GREDICS group to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Berger, P.L.; Luckmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality; Penguin Books: Auckland, New Zealand, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H. The Covid-19 Pandemic Is Exposing the Plague of Neoliberalism. Prax. Educ. 2020, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.A. Failed Citizenship and Transformative Civic Education. Educ. Res. 2017, 46, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Rodríguez, A.E. Educación para la ciudadanía: Una aproximación al estado de la cuestión. Enseñanza Cienc. Soc. Rev. Investig. 2008, 7, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovici, S. Des représentations collectives aux représentations sociales. Eléments pour une histoire. In Les Représentations Sociales; Jodelet, D., Ed.; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1989; pp. 62–86. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovici, S. Social Representations: Explorations in Social Psychology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, S.A. A Field Study of Selected Student Teacher Perspectives toward Social Studies. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 1984, XII, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.; Adler, S.A. Becoming an Elementary Social Studies Teacher: A Study of Perspectives. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 1985, XIII, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagès, J. El currículo de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales en la formación inicial del profesorado: Investigaciones sobre la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de la DCS. In Modelos, Contenidos y Experiencias en la Formación del Profesorado de Ciencias Sociales; Pagès, J., Estepa, J., Travé, G., Eds.; Universidad de Huelva: Huelva, Spain, 2000; pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sant, E.; Davies, I.; Santisteban, A. Citizenship and Identity: The Self-Image of Secondary School Students in England and Catalonia. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2016, 64, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, J.; Oller, M.; Muñoz, C. Desarrollo de identidades ciudadanas: Representaciones sociales sobre la participación en democracia tras las movilizaciones estudiantiles en Chile. In Deconstruir la Alteridad Desde la Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales: Educar para una Ciudadanía Global; Ruiz, C.R.G., Doreste, A.A., Mediero, B.A., Eds.; Universidad de las Palmas de Gran Canaria/AUPDCS: Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2016; pp. 246–254. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, A. Citizenship Education and Identity in Europe. REICE Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2007, 5, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, A.; Pagès, J. La educación democrática de la ciudadanía: Una propuesta conceptual. In Las Competencias Profesionales para la Enseñanza-Aprendizaje de las Ciencias Sociales Ante el Reto Europeo y la Globalización; Ávila, R.M., Atxurra, R.L., de Larrea, E.F., Eds.; AUPDCS y Universidad de Bilbao: Bilbao, Spain, 2007; pp. 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, A.; Pagès, J. A conceptual proposal for research on education for citizenship. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. 2009, 21, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès, J. La formación del pensamiento social. In Enseñar y Aprender Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia; Benejam, P., Pagès, J., Eds.; Horsori: Barcelona, Spain; Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 1997; pp. 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- García, F.F.; De Alba, N. La educación para la participación ciudadana entre dos polos: El simulacro escolar y el compromiso social. In Educar para la Participación Ciudadana en la Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales; De Alba Fernández, N., García Pérez, F.F., Santisteban, A., Eds.; Díada/AUPDCS: Sevilla, Spain, 2007; pp. 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, A.; González-Monfort, N. Education for Citizenship and Identities. In Handbook of Research on Education for Participative Citizenship and Global Prosperity; Pineda-Alfonso, J.A., de-Alba-Fernandez, N., Navarro-Medina, E., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 551–567. [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert, J. La Formación del Pensamiento Crítico: Teoría y Práctica; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, A. La formación del pensamiento social y el desarrollo de las capacidades para pensar. In Didáctica del Conocimiento del Medio Social y Cultural en la Educación Primaria; Pagès, J., Santisteban, A., Eds.; Síntesis: Barcelona, Spain, 2011; pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, E.W. Social studies and critical thinking. In Critical Thinking and Learning. An Encyclopedia for Parents and Teachers; Kincheloe, J., Weil, D., Eds.; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 2004; pp. 383–388. [Google Scholar]

- Tosello, J. Identities and Social Sciences Teaching. Study of Cases from Three Places of The World. REIDICS Rev. Investig. Didáctica Cienc. Soc. 2018, 2, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santisteban, A.; Pagès, J. Una nueva lectura de los programas de estudios para la formación inicial del profesorado de didáctica de las ciencias sociales: Mirando el presente y el futuro. In Enseñar y Aprender Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales: La Formación del Profesorado Desde una Perspectiva Sociocrítica; Hortas, M.J., Dias, A., de Alba, N., Eds.; AUPDCS/Politécnico de Lisboa/Escola Superior de Educação: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019; pp. 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- González-Valencia, G.; Santisteban, A. Civic Education in Colombia: Between Tradition and Transformation. Rev. Educ. Educ. 2016, 19, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.F. A didactic model to change education: The school research model. Scr. Nova Rev. Electrónica Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2000, IV. Available online: http://www.ub.es/geocrit/sn-64.htm (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- García, F.F.; De Alba, N. Can the schools of the 21 st century educate the citizens of the 21 st century? Scr. Nova. Rev. Electrónica Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2008, XII. Available online: http://www.ub.es/geocrit/sn/sn-270/sn-270-122.htm (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Legardez, A. L’enseignement des questions sociales et historiques, socialement vives. Cart. Clio 2003, 3, 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, A. Social Sciences Education Based on Social Issues or Controversial Issues: State of the Art and a Research Results. Futuro Pasado 2019, 10, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutiaux-Guillon, N. Enseigner L’histoire en Contexte de Pluralité Identitaire; La revue française d’éducation comparée; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2018; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Massip, M.; Castellví, J.; Pagès, J. La historia de las personas: Reflexiones desde la historiografía y de la didáctica de las ciencias sociales durante los últimos 25 años. Panta Rei Rev. Digit. Hist. Didáctica Hist. 2020, 14, 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagès, J. Ciudadanía global y enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales. Retos y posibilidades para el futuro. REIDICS Rev. Investig. Didáctica Cienc. Soc. 2019, 5, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Balcells, L.; Fernández Albertos, J.; Kuo, A. Secession and Social Polarization: Evidence from Catalonia; WIDER Working Paper, No. 2021/2; The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER): Helsinki, Finland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-9256-936-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Código de buenas prácticas en la investigación. Acuerdo de Consejo de Gobierno de 30 de septiembre de 2020. Consultado el 26 de agosto de 2021. Available online: https://www.uab.cat/doc/DOC_CBP_ES (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Tosello, J. La Construcción de las Identidades Desde la Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales. Estudios de Casos de Profesores/as de Sudáfrica, Argentina y Cataluña. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Repáraz, M.; Arbués, E.; Naval, C.; Ugarte, C. El índice cívico de los universitarios: Sus conocimientos, actitudes y habilidades de participación social. Rev. Española Pedagog. 2015, 260, 23–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methology, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter, A.M. A New World Order; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Veugelers, W. La educación moral y para la ciudadanía en el siglo XXI. In La Educación Ciudadana en un Mundo en Transformación: Miradas y Propuestas; Mínguez Vallejos, R., Romero Sánchez, E., Eds.; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weistheimer, J. Civic Education and the Rise of Populist Nationalism. Peabody J. Educ. 2019, 94, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).