Abstract

The sociological understanding of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination offers the possibility to understand society better as the processes that shape health beliefs and influence HPV vaccine decisions relate to gender, power, and identity. This research aimed to locate, select, and critically assess scientific evidence regarding the attitudes and practices towards HPV vaccination and its social processes with a focus on health equity. A scoping review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and the recommendations made by the Joanna Briggs Institute was undertaken. Medline and Scopus were searched from their start date until December 2021. The review followed the Population/Concept/Context (PCC) inclusion criteria: Population = General population, adults and adolescents, Concept = Empirical data on determinants of HPV vaccination, Context= Studies on attitudes and practices towards HPV vaccination and its social processes with a focus on gender, class, and ethnic/racial inequalities. Of the 235 selected articles, 28 were from European countries and were the focus of this review, with special attention to socio-economic determinants in HPV vaccine hesitancy in Europe, a region increasingly affected by vaccination public distrust and criticism. Barriers and facilitators of HPV vaccine uptake and determinants of immunization were identified. Given the emphasis on health equity, these data are relevant to strengthening vaccination programs to promote vaccination for all people.

1. Introduction

The sociological understanding of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, which varies between and within countries [1], offers the possibility to better understand society as vaccination processes, and in particular, vaccination against HPV–a widespread and sexually transmitted viral infection responsible for approximately 70% of cervical cancer cases in the world [2]–are constructed within social, cultural, and institutional contexts that produce normative notions on rights and responsibilities of health citizenship. The distinctive fact about the HPV vaccine’s target being sexually transmitted links it to longstanding controversies around sex, gender, and young women’s bodies and sexual behaviors [3,4]. Cervical cancer can serve as an example of the systematic disadvantages that women experience due to social and sexual inequalities and enables us to understand how gender intersects other social hierarchies such as class and ethnicity/race to (re)produce social inequalities in health [5,6]. Although both men and women are at risk of developing HPV-related cancers, social campaigns regarding vaccination against HPV are aimed mainly at the prevention of cervical cancer for women [7]. The promotion of HPV vaccination is surrounded by feminization and moralization processes, influencing the understanding of HPV vaccination and the accessibility of vaccination as preventive health behavior. The stigma associated with HPV vaccination due to the stereotypical perception of the HPV vaccine as a facilitating agent of immoral sexual behaviors influences not only the decision-making process but also the discrimination against those who get the vaccine, serving as social control for girls and women [8]. This adds to the fact that knowledge about sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is frequently obtained from social campaigns, media, and the Internet, due to an absence of comprehensive sexuality education programs, which accentuates health disparities among underserved and disadvantaged populations (e.g., sexual and gender minorities) [9].

HPV vaccination coverage rates are affected by social norms (including of one’s family, friends, healthcare professionals, and religious or community leaders) [10]. Social sciences research has been describing the processes through which individuals receive and manage medical definitions and interventions for their bodies, such as marketing from pharmaceutical industries and professional claims of knowledge [8,11,12,13,14,15]. Trust in doctors, nurses, and other health professionals, in the healthcare system and the pharmaceutical industry, and patient-centeredness in care, influence health-related beliefs and HPV vaccine decision making [16,17,18,19,20]. It is important to better understand the social determinants of vaccination and the system-level barriers to HPV vaccine uptake [21]. Among the existing theoretical frameworks to help define vaccination behaviors, the 5As’ practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake focusing on access, affordability, awareness, acceptance, and activation seemed to be most adequate [22].

A literature review represents an opportunity to look at how intersecting gender, age, class, ethnicity/race, and other social inequalities in different contexts shape health care decisions.

The HPV vaccine coverage rates have been suboptimal in some European countries, particularly in Eastern Europe, but also in Ireland, France, and Denmark. Variations can be partly explained by contextual and implementation factors, such as vaccine delivery (schools or public or private health systems), depending on the country and immunization program [10]. Moreover, vaccination is increasingly suffering from public distrust and criticism in Europe. The existing literature suggests the need for reviews looking specifically at socio-economic determinants in HPV vaccine hesitancy to support the development of context-specific interventions to improve confidence in HPV vaccination [10]. Therefore, this review aims to characterize the existing research on attitudes and practices toward HPV vaccination and the social and cultural construction processes involved in the understanding of the HPV vaccine to cancer prevention in Europe with a focus on health equity. The overarching research goal was to identify the social determinants of HPV under vaccination among diverse populations while exploring the following:

1: What are the barriers and facilitators of HPV vaccine uptake (based on the 5As) [23]?

2: What are the determinants of HPV vaccine uptake across gender, age, ethnicity/race, and population diversity?

3: Which practices and policies related to HPV vaccination can contribute to improving uptake and coverage routine to promote health and reduce health inequities?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

A scoping review was conducted to map and characterize the types of available evidence related to the social determinants of attitudes and practices towards HPV vaccination, and to identify knowledge gaps.

The review was undertaken following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [24] and the recommendations made by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), a global organization promoting and supporting evidence-based decisions that improve health and health service delivery [25].

2.2. Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was performed using Medline (via PubMed), and Scopus electronic databases, with combinations of the search terms, tailored to the syntax and functionality of each database. Searches were conducted on 14 December 2021 with no date range limitation. The following search query was used: “HPV vaccination” OR “Papillomavirus Vaccines”[Mesh] OR HPV OR “human papillomavirus” AND ((“Vaccination Hesitancy”[Mesh]) OR “Vaccination Refusal”[Mesh] OR “Attitude to Health”[Mesh] OR “Patient Acceptance of Health Care”[Mesh] OR “Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice”[Mesh]) AND (“Health Equity”[Mesh] OR “Social Justice”[Mesh] OR “Intersectional Framework”[Mesh] OR Intersectional* OR “health disparities” OR “Gender Equity”[Mesh] OR “Ethnicity”[Mesh] OR “Racial Groups”[Mesh])). Only English-written documents were considered eligible for inclusion.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The Population (or participants)/Concept/Context (PCC) method recommended by JBI to identify the main concepts in the primary review questions was used for the search strategy and the definition of inclusion criteria [25]: P (Population = General population, adults and adolescents), C (Concept = Empirical data on determinants of HPV vaccination), C (Context = Studies that report on attitudes and practices towards HPV vaccination and its social processes with a focus on gender, class, and ethnic/racial inequalities). All publications based on empirical studies (regardless of research design) were included. The exception was intervention studies, which were excluded, because of their distinguished features compared to observational studies. Book chapters, book reviews, vignette studies, study protocols, commentaries, guidelines, and editorials were also excluded.

Each relevant record was reviewed independently by the two authors, who screened titles and abstracts, and, when needed, full texts. A final decision was obtained for each record and uncertainties were resolved by discussion between the two authors.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

For all the included articles, the following data were extracted: (1) author(s) and year of publication, (2) country and setting, (3) population (sample size, gender, age, nationality/ethnicity, and diversity), (4) rationale and aim, (5) design and methods, (6) HPV outcome(s), (7) overall results, (8) overall limitations, (9) and overall recommendations. Information regarding the journal’s title, publication quartile, and domain of work (i.e., the domain with the highest quartile in the year of the study publication according to the Scimago Journal & Country Rank) was also collected.

Methodological quality or risk of bias of the included articles was not appraised because it was not relevant nor necessary to the scoping review objectives [25].

Results were synthesized using a thematic approach on the relevant themes related to the barriers and facilitators of HPV vaccine uptake, and its social processes, with a focus on gender, class, and ethnic/racial inequalities.

3. Results

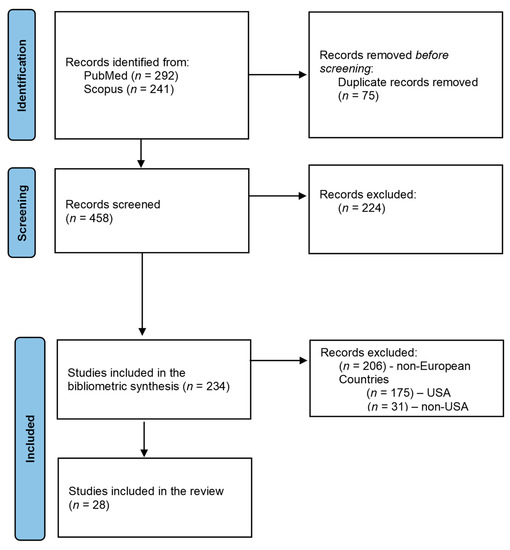

A total of 533 articles were identified, 291 in PubMed and 241 in Scopus. After duplicate removal (n = 75), 458 articles remained for screening. Of these, 224 were excluded because they were not empirical studies (i.e., literature reviews, study protocols, or commentaries/letters) or were intervention studies or did not focus on HPV vaccination attitudes or practices, or the study population was only health professionals. As a result, 234 publications could be included, with publication dates ranging from 2007 to 2021. Most of the studies (n = 175; 75%) were conducted in the United States of America (USA), and only 28 articles (12%) were conducted in European countries and were selected to be included in this review for mapping the state of the art and to reveal the specific trends in the field in Europe. A flow diagram providing the number of articles included and excluded at each stage is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram of the selection of the articles.

3.1. Who Is Being Studied and How?

The first publications (n = 2) were issued in 2008 (Table 1). The number of articles published each year ranged from zero articles in 2010, 2011, and 2013 to four articles in 2009, 2015, 2017, and 2018. All publications were in journals with an impact factor, and the majority ranked in the first quartile (21/28). Four articles were published in journals in the second quartile, and three articles in the third quartile. All articles were published in the medical and health sciences subject area, and one was also classified in social sciences (the journal of Medical Anthropology Quarterly).

Studies were conducted in 10 countries. Eleven studies were conducted in England [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], the first two publications in 2008, four in 2009 (the year that the government immunization program began with HPV vaccination of girls aged 12–13 years), and the last in 2020. All articles provided data concerning the role of ethnicity in HPV vaccination uptake.

Three studies were conducted in Romania [37,38,39], in 2012, 2016, and 2019, all focusing on Romanian parents/guardians’ vaccine hesitancy.

Three studies were conducted in the Netherlands [40,41,42], in 2014, 2015, and 2017, aiming to assess inequalities in vaccine uptake; one included a qualitative study with an intersectionality framework to capture the perceptions of migrant women from Somalia concerning cervical cancer prevention [42].

Three studies were conducted in Sweden [43,44,45], in 2014, 2017, and 2019, with different study designs and populations. The first study used individual interviews with parents who refused their daughters from receiving the HPV vaccination. The second study investigated HPV vaccination status in female adolescents and related sociodemographic factors, individual beliefs and knowledge about HPV prevention, and sexual experiences. The last study aimed to investigate inequities in HPV vaccine uptake 10 years after its introduction in the country, where three different delivery modes of the vaccine have existed since 2007.

Moreover, three studies were conducted in Denmark [46,47,48], one in 2015 and two in 2018, all using data from the Danish childhood immunization program.

Finally, five countries had one publication each, with different populations and approaches. The study conducted in Greece in 2020 focused on the vulnerable population of Roma women [49], while the study conducted in Poland in 2021 focused on Polish men [50]. Research conducted in Norway [51] and Spain [52] was centered on adolescent girls and parents, and the Italian study investigated factors related to HPV vaccination refusal in young adult women without starting or completing HPV vaccination [53].

The majority of the articles had as the main outcome HPV vaccination uptake and its determinants (n = 19), while others focused only on HPV vaccination intentions (n = 9). Twenty-two articles used a quantitative approach, mostly with a descriptive design, while six articles used a qualitative approach with individual interviews and focus groups.

Table 1 presents more details on the characteristics of the studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies.

| Author, Date | Journal, Quartile | Area of Expertise | Country | Population | Methods, Study Design | HPV Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberts et al., 2017 [40] | BMC Public Health, Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | The Netherlands | Parents/guardians of daughters (n = 1309) from different ethnic groups | Longitudinal study Database of the Youth Health Service of the Public Health Service of Amsterdam Self-completion questionnaire | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention and uptake |

| Amdisen et al., 2018 [46] | Vaccine, Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | Denmark | Girls who were residing in Denmark between their 12th and 13th birthday (n = 161,528) | Register-based cohort study Data from the Danish Vaccination Register were linked with demographic data from the Danish Civil Registration System | Determinants and uptake of the first dose of the HPV vaccine (HPV1) |

| Conroy et al., 2009 [26] | Journal of Women’s Health Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | England | Girls and women aged 13–26, of black, white, or other ethnicity (n = 262) | A baseline survey, linked with demographic data, gynecological history, and attitudes associated with vaccination at follow-up | Determinants of HPV vaccination uptake and follow-up |

| Craciun and Baban, 2012 [37] | Vaccine, Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | Romania | Romanian mothers aged 30–50 who decline vaccine of their daughters), aged 10–11 (n = 24) | Data from the project “Psychosocial, Political and Gendered Dimensions of Preventive Technologies in Bulgaria and Romania: HPV Vaccine Implementation”, Semi-structured interviews and focus groups | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention |

| Forster et al., 2015 [27] | BMC Public Health Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | England | Girls aged 15–16, of White, Black, Asian, or another ethnicity (n = 2163) | Data was collected through surveys from an ethnically diverse sample of girls from twelve London schools | Determinants of HPV vaccination status |

| Forster et al., 2017 [29] | Psycho-Oncology Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | England | Ethnic minority/White British parents of girls (36–62) (n= 33) | Data from parents was collected via interviews and analyzed using Framework Analysis | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention and uptake |

| Grandahl et al., 2014 [43] | Acta Paediatrica Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | Sweden | Parents who refused their daughters from receiving the HPV vaccination, aged 10–12 (n = 25) | Data from parents was gathered via interviews | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention and uptake |

| Grandahl et al., 2017 [44] | PLoS One Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | Sweden | Upper secondary school students, boys and girls aged 16 (n = 832) | Cross-sectional study Data from the project Prevention of HPV in a school-based setting Health Belief Model (HBM) and reports of cross-sectional studies | Determinants of HPV vaccination follow-up uptake and status |

| Hansen et al., 2015 [51] | Preventive Medicine Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | Norway | Girls and parents of Norwegian nationality (n = 90,842) | Data collected from national registries for all Norwegian girls eligible for routine school-based HPV vaccination and their registered mother and father were merged | Determinants of HPV vaccination uptake and follow-up |

| Marlow et al., 2008 [31] | Journal of Medical Screening Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | England | Women aged 25–64, of white or non-white ethnicity (n = 994) |

Random sampling of postcode address Self-reported cervical screening and intention to accept an HPV test; In a subsample (n = 296) with a young daughter’s self-reported willingness to accept HPV vaccination | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention |

| Marlow, et al., 2009 [30] | Vaccine, Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | England | Female students, aged 16–19, of White, Black, Asian, or another ethnicity (n = 367) | Participants from two further-education colleges reported on acceptability and attitudes (based on the Health Belief Model) after reading information about HPV | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention |

| Marlow et al., 2009 [32] | Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | England | Ethnic minority women (n = 750) and white British women (n = 200), aged 16–55+ | Cross-sectional study with quota sampling to ensure adequate representation of ethnic minority women and a comparison sample of white British women | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention |

| Marlow et al., 2009 [33] | Human Vaccines Q3 | Medical and Health Sciences | England | Black/Black British (n = 10) and Asian/Asian British mothers (n = 10) of daughters at least 16 years old | Face-to-face interviews | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention |

| Miko et al., 2019 [38] | Medicine Q3 | Medical and Health Sciences | Romania | Romanian parents/guardians (n = 452) | Cross-sectional survey based on the Matrix of Determinants for Vaccine Hesitancy designed by SAGE | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention |

| Møller et al., 2018 [47] | European Journal of Cancer Prevention Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | Denmark | Refugee girls (n = 3264) Danish-born girls (n = 19,584) | Register-based cohort design Data from the National Danish Health Service, identifying all contacts for HPV immunization in the ordinary and catch-up HPV immunization program | Determinants of HPV vaccination uptake |

| Mollers et al., 2014 [41] | BMC Public Health Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | The Netherlands | Girls aged 16–17, Dutch, Turkish, Moroccans, Surinamese, Antilleans, Arubans, and other (n = 2989) | Nationwide online questionnaire with knowledge and other variables associated with vaccination status | Determinants of HPV vaccination status |

| Navarro-Illana P. et al., 2018 [52] | Gaceta Sanitaria Q2 | Medical and Health Sciences | Spain | Adolescent girls and their parents, aged 25–60+, (n = 1278) | Cross-sectional study on knowledge and attitudes related to HPV infection and vaccine | Determinants of HPV vaccine intention and uptake |

| Pop, 2016 [39] | Medical Anthropology Quarterly Q1 | Medical and Health/Social Sciences | Romania | Parents from South Romania, women (n = 43) | In-depth semi-structured interviews, | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention |

| Restivo et al., 2018 [53] | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Q2 | Medical and Health Sciences | Italy | Women aged 18–21 without starting or completing HPV vaccination (n = 141) | A cross-sectional study using a telephone questionnaire, with items on HPV infection and vaccination knowledge based on the Health Belief Model framework | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention and uptake follow-up |

| Reszka et al., 2021 [50] | Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene (JPMH) Q3 | Medical and Health Sciences | Poland | Hetero and homosexual men, aged 14–39 (n = 169) | Cross-sectional study with open-ended, close-ended, and nominal, multiple-choice questions | Determinants of HPV vaccination status |

| Riza et al., 2020 [49] | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Q2 | Medical and Health Sciences | Greece | Vulnerable population of Roma women aged 18–70 (n = 142 in 2012; n = 122 in 2017) | Cross-sectional study, interviewer-administered questionnaire based on the behavioral model for vulnerable populations | Determinants of HPV vaccination status |

| Rockliffe et al., 2017 [34] | BMJ Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | England | Data from 195 schools obtained for girls from diverse ethnic backgrounds uptake rates | Uptake rates for the three recommended vaccine doses from 2008 to 2010 from schools combined to census data related to the postcode of each school for the ethnic characterization of the resident population | Determinants of HPV vaccination uptake |

| Salad et al., 2015 [42] | International Journal for Equity in Health Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | The Netherlands | Somali women aged 17–21, (n = 14); Somali mothers, two groups, aged 30–46 and 23–66 (n = 6) | Semi-structured interviews; thematic content analysis | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention |

| Schreiber et al., 2015 [48] | Journal of Adolescent Health Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | Denmark | Girls in childhood immunization program (n = 65,926) | Data obtained by linkage to Statistics Denmark and the Danish National Health Insurance Service Register | Determinants of HPV vaccination status uptake and follow-up |

| Spencer et al., 2014 [35] | BMJ Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | England | Mothers; daughters, aged 12–13 | Index of Multiple Deprivation scores and census ethnicity data | Determinants of HPV vaccination status and initiation |

| Stearns et al., 2020 [36] | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Q2 | Medical and Health Sciences | England | Men who have sex with men, ethnicity mostly white 84% (n = 115) | Cross-Sectional Survey Design | Determinants of HPV vaccination status and uptake |

| Walsh et al., 2008 [28] | BMC Public Health Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | England | Participants mix of social class and ethnicity aged 16–54 (n = 420) | Street survey with semi-structured interview questionnaire Setting: three areas of Birmingham to target a mix of social class and ethnicity | Determinants of HPV vaccination intention |

| Wang et al., 2019 [45] | Preventive Medicine Q1 | Medical and Health Sciences | Sweden | Girls born between 1990 and 2003 (n = 689,676) | Cumulative incidence of receiving the first dose of the vaccine | Determinants and uptake of the first dose of the HPV vaccine (HPV1) |

3.2. Barriers and Facilitators of Vaccination Uptake

All the included articles referred to barriers or facilitators of vaccine uptake. Access, acceptance, and activation were the most frequent themes, and awareness and affordability were less frequent. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccine uptake subthemes were identified and are summarized in Table 2.

- Access and Affordability

Demographic and socioeconomic status were common barriers to HPV vaccine uptake in different European countries [35,41,48,49]. Specific barriers were also reported for people with refugee/migrant or ethnic minority backgrounds [48,49,52]. For example, Spencer et al. combined the use of the index of multiple deprivations and census ethnicity data to explore the links between HPV vaccination and cervical screening uptake with deprivation and ethnic composition of the area of residence in a deprived region in England. Results revealed that girls from the most deprived areas were less likely to complete the three vaccine doses. The authors concluded that there is a group of women from disadvantaged backgrounds and with a higher concentration of ethnic minorities who miss both cervical screening and HPV vaccination [35].

Several socioeconomic predictors of HPV vaccination were found in a cohort study based on the national HPV childhood vaccination program in Denmark. Ethnicity was found to be a strong determinant of initiation and completion of HPV vaccination. A social gradient regarding education, income and employment status was also observed, where decreases in vaccine coverage were associated with girls whose mothers were more disadvantaged [48]. A cross-sectional study in the Netherlands also found that vaccination uptake was higher in low urbanized settings and among girls without a religious background [41].

In Southeast Europe, a cross-sectional study in Greece with various groups of vulnerable women found that nationality was related to knowledge and attitudes on cervical cancer etiology and the HPV vaccine, with native women demonstrating higher knowledge than migrant and Roma women. The findings also indicated that Roma women faced higher levels of marginalization and social exclusion compared to legalized migrant women [49]. Additional factors associated with limited knowledge on risk factors for cervical cancer and erroneous attitudes and perceptions on cervical cancer prevention (Pap smear and HPV vaccine) included older age, low educational level, housing conditions, and lack of insurance coverage [49]. The lower uptake of the HPV vaccine among refugee girls is a challenge to immunization programs in raising ethnically diverse societies [47].

Socioeconomic factors and education were among the identified facilitators of vaccine uptake [43], in addition to factors such as country of origin and time of residence as predictors of uptake in migrant populations [47]. Routine school-based vaccination and free-of-charge vaccination were also identified as providing equitable delivery, yet needing to be complemented with information campaigns designed to optimize the uptake of the HPV vaccine by reducing disparities in some socio-economic disadvantaged sub-groups with lower vaccine uptake [45,51]. A nationwide cohort study in Sweden, for example, compared three delivery modes of the vaccine and concluded that free-of-charge school-based HPV vaccination was the most effective and equitable delivery mode, including high-risk groups for cervical cancer [45].

Table 2.

Barriers and facilitators of vaccination uptake.

Table 2.

Barriers and facilitators of vaccination uptake.

| Barriers | Facilitators | |

|---|---|---|

| Access |

|

|

| Affordability |

|

|

| Awareness |

|

|

| Acceptance |

|

|

| Activation towards vaccination uptake |

|

|

A qualitative Swedish study among parents who did not consent to their daughters receiving the HPV vaccination showed that parents went through a complex decision process, in an equation of the perceived risks and benefits of the vaccine, leading to the choice to vaccinate, or not to. Reasons for HPV vaccination refusal relate to the belief that it was better for the daughter’s health and well-being. Given the private and intimate nature of the HPV vaccination (perceived as a behavioral vaccine), some parents chose not to vaccinate based on the fact that the common good of herd immunity was of minor interest compared with the best interests of their daughter. Another key reason for declining HPV vaccination was the perceived absence of sufficient knowledge about HPV and the vaccine. Parents rated the information received from the school health system unsatisfactory and preferred to postpone vaccination. Levels of trust in vaccinations, healthcare providers, and governments also were found to affect the complex HPV vaccine decision process [43].

There were less data on vaccine affordability. A study among vulnerable women in Greece pointed out the need to increase access by way of enlarging insurance coverage and reviewing screening recommendations. Improved healthcare delivery systems, towards more direct patient care, reduced delayed care, and appropriate preventive health services, were highlighted to reduce non-financial barriers to vaccination [49].

Enabling factors identified, such as insurance coverage for HPV vaccination, echo the ability of the person to navigate the healthcare system and in obtaining social benefits. Interventions to increase uptake in catch-up age groups must safeguard that vaccine costs are included [26].

- Awareness and Acceptance

Lack of information/knowledge or perceived need were frequently cited barriers to vaccination [27,29,32,37,39,42,43,49,50]. One cross-sectional study among young adult women in Italy showed that participants with more concerns about the safety and efficacy of HPV vaccination were less likely to be vaccinated. Results seem to indicate the need for delivering accurate and clear information about vaccine efficacy and safety to boost HPV vaccination coverage [53]. An exploratory study in Poland on the knowledge about HPV infection and HPV-related cancers also found that the danger is poorly understood among men. The authors suggest that healthcare professionals need to broaden their knowledge about the specific health needs of underserved populations such as LGBTQ+ communities to prevent health disparities [50].

Mollers et al. found that vaccinated girls in the Netherlands were less likely to have a religious background, and amongst those who professed religion, vaccinated girls were more often Catholic while unvaccinated girls were more often Protestant Christian. Moreover, no differences were found in terms of sexual risk behavior and knowledge of HPV infection and transmission, while differences were found in contraceptive use, the number of lifetime sexual partners, and opinions on the use of condoms after HPV vaccination and the protection of vaccination against all HPV types [41].

A six-month follow-up study conducted in 2006 shortly after the HPV vaccine was licensed in England found that young women with a history of an abnormal Pap test were less likely to have received the vaccine. This fact was confirmed by others [51]. On the contrary, identified predicted factors for HPV vaccination included the belief that one’s parents, partners, and clinicians recommended HPV vaccination [26].

A survey in Spain also pointed out that advice from the nurse and physician was the key factor in HPV vaccination [52]. This result adds to the understanding that social norms predict HPV vaccine intent and uptake [47].

Among the facilitators, the intention was a strong predictor of uptake, together with past childhood vaccination uptake. Furthermore, HPV vaccination intention and uptake are based on similar determinants in the different ethnic groups, meaning that interventions based on similar behavior change methods (e.g., psychological inoculation or peer modeling) could be designed with added actions to reach different ethnic populations [40].

- Activation towards vaccination uptake

Nurses and doctors lead the health processes of healthcare users, and the uptake of their recommendations [43,52]. Catch-up campaigns may improve immunization coverage with doctors’ and trusted individuals’ endorsements and promote vaccination as normative [47].

In the case of vulnerable populations, interventions to increase the prevention of cervical cancer, routine examination with the Pap test, and HPV vaccination need the healthcare delivery systems to be adapted accounting for cultural, social, and religious diversity [49]. Ethnic disparities in HPV vaccination may be understood in light of the levels of concern about the vaccine [29]. Interventions to increase immunization should be culturally tailored and community-based [29,33,40,42,49].

3.3. Attitudes and Beliefs about the HPV Vaccine

There are diverse health beliefs and objections to vaccination. Mollers et al. found that vaccinated and unvaccinated girls in the Netherlands were comparable in most sexual risk behaviors and had similar scores on knowledge of HPV infection and HPV transmission, but they differed for characteristics such as contraceptive use, the number of lifetime sexual partners, and their opinions on the use of condoms after HPV vaccination and the protection of vaccination against all HPV types. Sexually active vaccinated girls were more aware of the risk of HPV infection when engaging in unprotected sex [41].

Some studies mentioned the role of religious and cultural prohibitions on sex before marriage as a barrier to vaccination, related to low levels of awareness in some minority groups [35]. For some families, the HPV vaccination was not considered compatible with their life values. Building self-confidence in girls to delay sexual debut was chosen among other alternative methods of prevention [43].

Besides moral concerns, some studies indicate that there is a group of parents who consider that the vaccine is not necessary and/or serves the interest of the government or pharmaceutical companies. In this case, HPV vaccine decline is linked to the belief that vaccines are unnatural. Other reasons include the belief that vaccinations are used for population control [43]. A qualitative study in Romania points out that mothers’ main reasons for not vaccinating their daughters are the belief that the vaccine represents an “experiment that uses their daughters as guinea pigs”, the belief that the vaccine embodies a conspiracy theory to reduce the population, and mistrust in the health system [37].

4. Discussion

This study described barriers and facilitators of HPV vaccine uptake and identified determinants of under-immunization, reviewing data on European countries, where HPV vaccination has been gradually introduced in the national immunization programs since 2007. Given the chosen focus on health equity, these data are relevant to strengthening vaccination programs to promote vaccination for all people.

Health policies and practical implementation processes of HPV vaccination vary across European countries, as shown in Table 3, with information on HPV national immunization programs of the 10 countries covered in this review (Denmark, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom). In most countries, the HPV vaccine is administered in public health clinics, while countries such as Norway, Sweden, and the UK have established school vaccination programs, and Spain offers a combination of school and/or health centers depending on the region.

Table 3.

Status of HPV national immunization programs in the 10 EU/EEA countries under analysis (Denmark, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom).

Four of the analyzed countries (Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, and Poland) recommended gender-neutral vaccination, i.e., vaccination in all girls/women and boys/men, and one (the United Kingdom) for men from specific subgroups (men who have sex with men). However, information concerning HPV vaccination coverage rates is missing in men, indicating the need for better surveillance [54,55].

Access to and acceptance of HPV vaccination are key factors influencing vaccine uptake, therefore requiring multilevel action. Access barriers were the country of origin related to the sociodemographic status, and cultural beliefs [52]. Local delivery of HPV vaccination and organizational factors are central to reducing cervical cancer inequities [35], such as the role of school nurses in increasing HPV vaccine uptake among vulnerable groups [56].

A recent study that reviewed HPV vaccination coverage in 31 European countries has concluded that structured vaccination programs targeting females early in adolescence and free-of-charge vaccine administration were more frequently observed in countries with high vaccination coverage rates. Facilitating access to HPV vaccination by increasing onsite vaccine availability, sending invitations and reminders to attend for vaccination, and relying on schools as the main setting to administer the vaccine could also be important factors to achieve higher vaccine uptake [54].

The findings of this review have shown that besides HPV vaccination policies and practical implementation, HPV vaccination is also influenced by sociocultural factors and individual characteristics.

Religion has been shown to influence the vaccination decision-making process with certain religious or ideological groups being linked to anti-vaccination movements and outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases [57]. Some parents perceived their daughters to be too young to be vaccinated and to be sexually active. A more flexible vaccination schedule with the option of offering vaccinations later and providing more adequate and comprehensive explanations about the virus and the vaccine could be strategies to improve vaccine uptake [43].

Interventions aimed at increasing HPV vaccine coverage should be focused on raising health professionals’ HPV awareness to better inform patients about HPV infection and vaccination [52]. The dissemination of culturally adapted and unbiased information, together with the opportunity to talk about the vaccine with healthcare professionals, could contribute to trust in public government recommendations and increase vaccine coverage [43]. As the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed, the success of public health campaigns relies on trust in leaders, experts, and medical professionals, however social determinants like race, class, and gender influence vaccines attitudes and beliefs, on the one hand, and also the state, on the other, because interactions with the state are multifaceted, bureaucratic, and can be coercive. Further investigation on attitudes toward immunization among marginalized populations is needed to identify alternative practices from dominant narratives that could better inform inclusive public health outreach [58].

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Research

The results of this review should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, only two different databases were consulted for locating papers with no additional search strategy, such as searching references of the included papers or references of literature reviews identified during the screening process. This may have limited the inclusion of more articles from the social sciences field, although Scopus is among the largest databases, with a wide global and regional coverage of scientific journals. A strong point, nevertheless, is that the search strategy was comprehensive and followed the recommendations made by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [25], such as the Population/Concept/Context method, to identify the main concepts and the definition of inclusion criteria.

The second limitation is that only the studies conducted in European countries were included in this review, with no inclusion of comparisons with other contexts for a broader mapping of the state of the art regarding the attitudes and practices towards HPV vaccination and its social processes. Given the great variability in terms of the social, cultural, and institutional vaccine contexts and national vaccination programs, efforts were made to add more knowledge about the European contexts, that were less investigated, to better identify tailored and evidence-informed strategies.

Finally, all articles, independently of the study design or quality, were included to jointly present findings, which may also be considered a limitation. However, this review aimed to summarize the scientific evidence regarding the barriers and facilitators with a focus on health equity; therefore, all identified articles were included to facilitate the overview of the key factors influencing vaccine uptake.

4.2. Recommendations for Research and Action

This review is not representative of the European region, considering that included studies came from only ten countries, largely focusing on Western Europe. Given that all EU/EEA countries have introduced HPV vaccination in their national programs, and many countries have recently changed or are changing to a gender-neutral HPV vaccination [59], there is a need for more data on HPV vaccination with disaggregated data for diversity, which is rarely collected by national data. Monitoring HPV vaccination uptake and policies at a European level, as well as sharing experiences between countries, could contribute to the success of HPV vaccination programs and address health inequities [54].

Certain subpopulations were not well reported and did not reflect on how different intersecting identities place people at multiple disadvantages, such as LGBT people, different migrant and ethnic minorities, and several other vulnerable and most at-risk-identified populations. This indicates a need for HPV vaccine uptake datasets in Europe that disaggregate by diversity to monitor HPV vaccination inequalities. Sub-analyses on vulnerable populations could be conducted with disaggregated data from general population studies.

Joining vaccination strategies with other recommended healthcare services for populations burdened by HPV infection and HPV-related diseases, such as LGBT people, could increase vaccination in these populations where HPV vaccine acceptability tends to be high [9].

Action plans to address specific perceptions and barriers towards HPV vaccination should be co-designed with the most at-risk-identified populations and inclusive catch-up initiatives could be considered drawing on new models of good practice in vaccine delivery employed during the COVID-19 pandemic [23].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A.; methodology, V.A.; analysis, V.A. and B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A.; writing—review and editing, V.A. and B.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bruni, L.; Saura-Lázaro, A.; Montoliu, A.; Brotons, M.; Alemany, L.; Diallo, M.S.; Afsar, O.Z.; LaMontagne, D.S.; Mosina, L.; Contreras, M.; et al. HPV vaccination introduction worldwide and WHO and UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage 2010–2019. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 2021, 144, 106399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, L.M.; Casper, M.J. A tale of two technologies: HPV vaccination, male circumcision, and sexual health. Gend. Soc. 2009, 23, 790–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, M.J.; Carpenter, L.M. Sex, drugs, and politics: The HPV vaccine for cervical cancer. Sociol. Health Illn. 2008, 30, 886–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozhar, H.; McKee, M.; Spadea, T.; Veerus, P.; Heinävaara, S.; Anttila, A.; Senore, C.; Zielonke, N.; de Kok, I.M.C.M.; van Ravesteyn, N.T.; et al. Socio-economic inequality of utilization of cancer testing in Europe: A cross-sectional study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 26, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perehudoff, K.; Vermandere, H.; Williams, A.; Bautista-Arredondo, S.; de Paepe, E.; Dias, S.; Gama, A.; Keygnaert, I.; Longatto-Filho, A.; Ortiz, J.; et al. Universal cervical cancer control through a right to health lens: Refocusing national policy and programmes on underserved women. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2020, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logel, M.; Laurie, C.; El-Zein, M.; Guichon, J.; Franco, E.L. A Review of Ethical and Legal Aspects of Gender-Neutral Human Papillomavirus Vaccination. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2022, 31, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, J.Y.M.; Fung, T.K.F.; Leung, L.H.M. Social and cultural construction processes involved in HPV vaccine hesitancy among Chinese women: A qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meites, E.; Wilkin, T.J.; Markowitz, L.E. Review of human papillomavirus (HPV) burden and HPV vaccination for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men and transgender women in the United States. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 2016007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karafillakis, E.; Simas, C.; Jarrett, C.; Verger, P.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Dib, F.; de Angelis, S.; Takacs, J.; Ali, K.A.; Celentano, L.P.; et al. HPV vaccination in a context of public mistrust and uncertainty: A systematic literature review of determinants of HPV vaccine hesitancy in Europe. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2019, 15, 1615–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.E.; Shim, J.K.; Mamo, L.; Fosket, J.R.; Fishman, J.R. Biomedicalization: Technoscientific Transformations of Health, Illness, and U.S. Biomedicine. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2003, 68, 161–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giami, A.; Perrey, C. Transformations in the medicalization of sex: HIV prevention between discipline and biopolitics. J. Sex Res. 2012, 49, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, P. The Shifting Engines of Medicalization. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, J.A. Vaccine Refusal and Pharmaceutical Acquiescence: Parental Control and Ambivalence in Managing Children’s Health. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 85, 106–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamo, L.; Pérez, A.E.; Rios, L. Human papillomavirus self-sampling: A tool in cancer prevention and sexual health promotion. Sociol. Health Illn. 2022, 44, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacArthur, K.R. Beyond health beliefs: The role of trust in the HPV vaccine decision-making process among American college students. Health Sociol. Rev. 2017, 26, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, N.; Chen, Y.; O’Reilly, A.M.; Fang, C.Y. The role of trust in HPV vaccine uptake among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States: A narrative review. AIMS Public Health 2021, 8, 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caso, D.; Carfora, V.; Starace, C.; Conner, M. Key Factors Influencing Italian Mothers’ Intention to Vaccinate Sons against HPV: The Influence of Trust in Health Authorities, Anticipated Regret and Past Behaviour. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.L.; Hernandez, N.D.; Rollins, L.; Akintobi, T.H.; McAllister, C. HPV vaccine awareness and the association of trust in cancer information from physicians among males. Vaccine 2017, 35, 2661–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fenton, A.T.; Elliott, M.N.; Schwebel, D.C.; Berkowitz, Z.; Liddon, N.C.; Tortolero, S.R.; Cuccaro, P.M.; Davies, S.L.; Schuster, M.A. Unequal interactions: Examining the role of patient-centered care in reducing inequitable diffusion of a medical innovation, the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 200, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, D.M.; Benard, V.; Roland, K.B.; Watson, M.; Liddon, N.; Stokley, S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014, 168, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.; Robinson, K.; Vallée-Tourangeau, G. The 5As: A practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine 2016, 34, 1018–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, A.F.; Farah, Y.; Deal, A.; Rustage, K.; Hayward, S.E.; Carter, J.; Knights, F.; Goldsmith, L.P.; Campos-Matos, I.; Wurie, F.; et al. Defining the determinants of vaccine uptake and undervaccination in migrant populations in Europe to improve routine and COVID-19 vaccine uptake: A systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e254–e266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2021, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, K.; Rosenthal, S.L.; Zimet, G.D.; Jin, Y.; Bernstein, D.I.; Glynn, S.; Kahn, J.A. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake, predictors of vaccination, and self-reported barriers to vaccination. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009, 18, 1679–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, A.S.; Waller, J.; Bowyer, H.L.; Marlow, L.A.V. Girls’ explanations for being unvaccinated or under vaccinated against human papillomavirus: A content analysis of survey responses. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, C.D.; Gera, A.; Shah, M.; Sharma, A.; Powell, J.E.; Wilson, S. Public knowledge and attitudes towards Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccination. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, A.S.; Rockliffe, L.; Marlow, L.A.V.; Bedford, H.; McBride, E.; Waller, J. Exploring human papillomavirus vaccination refusal among ethnic minorities in England: A comparative qualitative study. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1278–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, L.A.V.; Waller, J.; Evans, R.E.C.; Wardle, J. Predictors of interest in HPV vaccination: A study of British adolescents. Vaccine 2009, 27, 2483–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, L.A.V.; Waller, J.; Wardle, J. Sociodemographic predictors of HPV testing and vaccination acceptability: Results from a population-representative sample of British women. J. Med. Screen. 2008, 15, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlow, L.A.V.; Wardle, J.; Forster, A.S.; Waller, J. Ethnic differences in human papillomavirus awareness and vaccine acceptability. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlow, L.A.V.; Wardle, J.; Waller, J. Attitudes to HPV vaccination among ethnic minority mothers in the UK: An exploratory qualitative study. Hum. Vaccin. 2009, 5, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockliffe, L.; Waller, J.; Marlow, L.A.V.; Forster, A.S. Role of ethnicity in human papillomavirus vaccination uptake: A cross-sectional study of girls from ethnic minority groups attending London schools. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, A.M.; Roberts, S.A.; Brabin, L.; Patnick, J.; Verma, A. Sociodemographic factors predicting mother’s cervical screening and daughter’s HPV vaccination uptake. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2014, 68, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stearns, S.; Quaife, S.L.; Forster, A. Examining Facilitators of HPV Vaccination Uptake in Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Cross-Sectional Survey Design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craciun, C.; Baban, A. Who will take the blame?’: Understanding the reasons why Romanian mothers decline HPV vaccination for their daughters. Vaccine 2012, 30, 6789–6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miko, D.; Costache, C.; Colosi, H.A.; Neculicioiu, V.; Colosi, I.A. Qualitative Assessment of Vaccine Hesitancy in Romania. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019, 55, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop, C.A. Locating Purity within Corruption Rumors: Narratives of HPV Vaccination Refusal in a Peri-urban Community of Southern Romania. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2016, 30, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberts, C.J.; van der Loeff, M.F.S.; Hazeveld, Y.; de Melker, H.E.; van der Wal, M.F.; Nielen, A.; el Fakiri, F.; Prins, M.; Paulussen, T.G.W.M. A longitudinal study on determinants of HPV vaccination uptake in parents/guardians from different ethnic backgrounds in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollers, M.; Lubbers, K.; Spoelstra, S.K.; Weijmar-Schultz, W.C.M.; Daemen, T.; Westra, T.A.; van der Sande, M.A.B.; Nijman, H.W.; de Melker, H.E.; Tami, A. Equity in human papilloma virus vaccination uptake?: Sexual behaviour, knowledge and demographics in a cross-sectional study in (un)vaccinated girls in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salad, J.; Verdonk, P.; de Boer, F.; Abma, T.A. A Somali girl is Muslim and does not have premarital sex. Is vaccination really necessary?’ A qualitative study into the perceptions of Somali women in the Netherlands about the prevention of cervical cancer. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandahl, M.; Oscarsson, M.; Stenhammar, C.; Nevéus, T.; Westerling, R.; Tydén, T. Not the right time: Why parents refuse to let their daughters have the human papillomavirus vaccination. Acta Paediatr. 2014, 103, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandahl, M.; Larsson, M.; Dalianis, T.; Stenhammar, C.; Tydén, T.; Westerling, R.; Nevéus, T. Catch-up HPV vaccination status of adolescents in relation to socioeconomic factors, individual beliefs and sexual behaviour. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ploner, A.; Sparén, P.; Lepp, T.; Roth, A.; Arnheim-Dahlström, L.; Sundström, K. Mode of HPV vaccination delivery and equity in vaccine uptake: A nationwide cohort study. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 2019, 120, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdisen, L.; Kristensen, M.L.; Rytter, D.; Mølbak, K.; Valentiner-Branth, P. Identification of determinants associated with uptake of the first dose of the human papillomavirus vaccine in Denmark. Vaccine 2018, 36, 5747–5753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, S.P.; Kristiansen, M.; Norredam, M. Human papillomavirus immunization uptake among girls with a refugee background compared with Danish-born girls: A national register-based cohort study. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. Off. J. Eur. Cancer Prev. Organ. 2018, 27, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, S.M.S.; Juul, K.E.; Dehlendorff, C.; Kjær, S.K. Socioeconomic predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination among girls in the Danish childhood immunization program. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2015, 56, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riza, E.; Karakosta, A.; Tsiampalis, T.; Lazarou, D.; Karachaliou, A.; Ntelis, S.; Karageorgiou, V.; Psaltopoulou, T. Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions about Cervical Cancer Risk, Prevention and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) in Vulnerable Women in Greece. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reszka, K.; Moskal, Ł.; Remiorz, A.; Walas, A.; Szewczyk, K.; Staszek-Szewczyk, U. Should men be exempted from vaccination against human papillomavirus? Health disparities regarding HPV: The example of sexual minorities in Poland. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2021, 62, E386–E391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, B.T.; Campbell, S.; Burger, E.; Nygård, M. Correlates of HPV vaccine uptake in school-based routine vaccination of preadolescent girls in Norway: A register-based study of 90,000 girls and their parents. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 2015, 77, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Illana, P.; Navarro-Illana, E.; Vila-Candel, R.; Díez-Domingo, J. Drivers for human papillomavirus vaccination in Valencia (Spain). Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restivo, V.; Costantino, C.; Fazio, T.F.; Casuccio, N.; D’Angelo, C.; Vitale, F.; Casuccio, A. Factors Associated with HPV Vaccine Refusal among Young Adult Women after Ten Years of Vaccine Implementation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen-Huu, N.; Thilly, N.; Derrough, T.; Sdona, E.; Claudot, F.; Pulcini, C.; Agrinier, N. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage, policies, and practical implementation across Europe. Vaccine 2020, 38, 1315–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanni, P.; Faivre, P.; Lopalco, P.L.; Joura, E.A.; Bergroth, T.; Varga, S.; Gemayel, N.; Drury, R. The status of human papillomavirus vaccination recommendation, funding, and coverage in WHO Europe countries (2018–2019). Expert Rev. Vaccines 2020, 19, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, T.; Holmes, A.H. Persistence and partnerships: School nurses, inequalities and the HPV vaccination programme. Br. J. Sch. Nurs. 2013, 8, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournet, N.; Mollema, L.; Ruijs, W.L.; Harmsen, I.A.; Keck, F.; Durand, J.Y.; Cunha, M.P.; Wamsiedel, M.; Reis, R.; French, J.; et al. Under-vaccinated groups in Europe and their beliefs, attitudes and reasons for non-vaccination; two systematic reviews. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, C.; Reich, J.A. Black Mothers and Vaccine Refusal: Gendered Racism, Healthcare, and the State. Gend. Soc. 2022, 36, 525–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colzani, E.; Johansen, K.; Johnson, H.; Celentano, L.P. Human papillomavirus vaccination in the European Union/European Economic Area and globally: A moral dilemma. Euro Surveill. Bull. Eur. Sur Les Mal. Transm. Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2021, 26, 2001659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).