1. Introduction

Recent studies have shown that Generation Z, born between 1995 and 2010, during the emergence of the Internet and new technologies, experience their daily lives whilst permanently connected to online platforms and their contents [

1]. The day-to-day of these young adults is underscored by the presence of the new media, which has implications for their personal, social, and professional lives. For developed societies, access to the Internet and digital platforms is widespread. For example, over 3.7 million individuals have Internet access in Portugal, according to PORDATA [

2]. There is an upward trend based on the growth witnessed since 1997, when there were only 88,670 people with Internet access. Commenting on the Portuguese case, Simões et al. [

3] stated that access to the new media has increased significantly in recent years, particularly at home, where the media online practices mainly concern leisure (social media, videogames, and music). These findings can carry over to other European countries such as Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain, and Romania [

4].

Young adults are immersed in this digital and technological ecosystem, actively consuming these platforms—this carries ramifications in terms of behavior reformulation both at a personal and social level. In a study [

5] describing online activity metrics among 1824 Portuguese children and youths in order to assess their digital media practices and online consumption, the authors concluded that the everyday lives of these users are characterized by intensive online engagement. Furthermore, the study also stated that juvenile culture is built around digital platforms. The authors also ascertained that almost 90% of youths go online daily, mainly through laptops or mobile phones. In the collective context of socialization, mediated through the online world, these practices emerge mostly as recreational (listening to music online, watching videos online, or engaging in social media). Internet usage as a means to academic ends is not prominent.

Understanding these matters regarding children and youths is a consistent goal within national and international academia [

3,

4,

6,

7,

8,

9]. However, there is a need to delve deeper into the online practices of young people who are now coming into adulthood, and their ramifications in their personal, social, political, academic, and professional contexts. Within the scope of this issue, we consider that it would be exciting to research further the possibility of the excessive consumption of the Internet [

1] as a cause of risk for the users’ health. The use of technology may have its advantages, at the cognitive and motor levels, for example, and as a learning aid [

10]. However, technological advances and the ease of access to these platforms in developed countries tend to significantly increase the time that young people are connected to these devices, which in turn may have profound health implications regarding behavioral dependency [

11]. Gómez-Galán et al. [

12] state that University students are heavy Internet users. In certain situations, addiction to online social networks can result from depression, harassment, and anxiety, affecting their daily lives, including their academic responsibilities.

This subject is more relevant in light of the historical moment we live in, provoked by the pandemic, which forced people into isolation. This new lifestyle increased the use of media to engage with family and peers, and also caused new work dynamics and the redefinition of time, space, and the dynamic of media consumption in our hyper-connected homes [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

This research concerns the perceptions of young adults who are university students, understood as belonging to generation Z, regarding their digital media practices in a pandemic context. Furthermore, the study approaches the consequences of the permanent connection to these new formats, such as the risk of developing behavioral dependence expressed through risk factors such as mood swings, intolerance, irritability and depression, sleep disorders, loss of concentration, emotional fragility, and social isolation, among others. Contextualizing the approach within Communication Studies, this study is based on striking a balance between the premises of Mass Communication Research. More particularly, we examine the possibility that access to media and technology carries health risks as well as those of sociocultural theories, shifting the attention from technology to audiences, and emphasizing personal and contextual circumstances as determinant elements for the uses and the understanding of these, and the potentially negative consequences thereof.

On the other hand, although several studies have already been carried out on the negative impacts of social media use [

18,

19], other studies also highlight the importance of more academic inquiries into social media use [

20,

21,

22]. The new studies are necessary because the “COVID-19 crisis is still actual and novel (...) publications on online addictive behaviors are unbalanced and limited, depending on countries, and some conclusions are speculative” [

23] (p. 16).

Finally, these issues have significant implications from the point of view of digital literacy, calling for the implementation of measures to develop skills that allow young people to get the most out of technology and learn to manage their relationship with digital tools more positively, reversing or preventing possible health consequences. In this context, and highlighted by the potential adverse effects of the new pandemic, active intervention is requested from the primary mediating contexts: the family, formal learning spaces, and public health institutions and professionals working in psychology. This mediation can hopefully be expressed through permanent monitoring and constructive and evaluative awareness regarding the less-good adjuvant side of using the new media.

2. Generation Z: The Mundane, Technology, and Sociability

Generation Z includes all individuals born between 1995 and 2010, in the age of the Internet and technology. The generation of digital natives was coined by Marc Prensky in 2001 in the On the Horizon journal. This generation is also known for its strong sense of ethics and social responsibility, passion for travelling and discovering the world, online social relationships, and difficulties in taking on work commitments and rules that limit time and space. However, this group also faces work-related setbacks, as a product of the transformations at the sociopolitical, geographical, and economic levels which are relevant to organizations, respective operational models and employability policies. These issues are reshaping their way of life, living the present, and planning the future. The Portuguese National Institute of Statistics published a report titled “Young people in the labor market” (“Jovens no mercado de trabalho” in Portuguese), in which it identified problems associated with the experience of young people (aged 15 to 34 years) in terms of education and employment. This analysis shows that qualification levels have gradually risen, i.e., the number of young people pursuing higher education has increased. However, even if the unemployment levels for this group have fallen, many still struggle to obtain their first job and ensure job stability. The latter is a very worrying and prominent issue in the public and political debate, where there is a clamoring for measures to help reduce uncertainty and job insecurity. For this reason, we see, on the one hand, an increase in the number of qualified young people choosing to leave their country of origin. On the other hand, we see the possibility that those who stay will suffer repercussions in terms of physical and mental health, with consequences for the family and social relationships, as has been noted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (OSHA).

In terms of access to and involvement with media and technology, young people naturally see these platforms in their daily lives. They are used to having access to a world of information like no other generation did, and are also qualified to help future generations to use technologies while, at the same time, qualifying to be employed in organizations with a solid commitment to this sector. “Transformed” by media and technology, this generation, according to Prensky [

24], has unique characteristics and digital literacy skills acquired by the permanent use of platforms. However, from another perspective, which we agree with, some authors are suspicious of the mechanistic approach characterizing Prensky’s vision, and consider that the skills for the use of technology are not innately acquired. Furthermore, these authors also consider that it is not enough to have grown up with these platforms to develop digital skills.

Despite this apparent lack of consensus in the literature, it is undeniable that media and technology increasingly occupy a place as agents of socialization from an early age, reconfiguring sociability and contributing, in their way, to the apprehension and assimilation of aspects of the world. Although the concept of socialization is ambivalent and subject to multiple debates [

25], it is undeniable that it is a process of constructing the individual in themselves and the world through appropriation, reinvention, and reproduction. Several actors and contexts intervene. Moreover, in this context, from an early age, the media are privileged elements in this journey. Studies have shown that the process of mediatization marks the daily life of the new generations in such a way that an analysis of their worlds that does not take into consideration the media in its most varied formats is insufficient to understand how these generations appropriate reality and construct their visions of themselves and the world. Therefore, the media function as knowledge networks of reality [

26], and as permanent references in growth, personal and social development, and learning [

27].

Inês Amaral [

28] recalls that new technologies undeniably influence individuals’ and societies’ lives. They are networks with direct implications for the construction of representations about the world and how we relate to it and others. The author advocates that the development of the technological and digital world promotes the emergence of new forms of culture, new social relationships, communities in virtual environments, and new behaviors:

There is an online social revolution underway regarding the use and appropriation of technology. People change their behaviors: they work, live, and think in networks. (...) The social Internet is understood as all the interactive devices that allow communication and interaction in a collective model and explore multiple innovations that induce social and communicational change through technology. (...) The Internet introduced and has been maximizing the communicational paradigm of individualization.

In this sense, younger generations know and maximize experiences in virtual contexts, and are precursors of new social, geographical, economic, cultural, and educational frameworks. They express new ways of being, learning, working, consuming, relating, and living, feeding new paradigms and academic debates that seek to effectively understand what these new groups are and how they know the world and place themselves in it.

Thus, we are talking about a group with particular characteristics that simultaneously drive transformations in distinct generational groups and, in general, society. When we look at the evolutionary path of media and technology, we see that television has been a significant milestone in the transformation of children and teenagers’ socialization by allowing contact with contents and realities that, until then, were not part of the children’s world. Therefore, this medium is a mediating element of diverse and distinct facts that children and youngsters did not know, and a reference in the process of self-understanding.

Although television continues to be an integrated medium in children’s daily lives, it is still very present in the domestic space and offers content that these audiences appreciate. The growth in access to and use of the Internet by children and young people is also remarkable. In this regard, the EU Kids Online project, which involved several international partners, sought to understand better these practices related to the Internet and the digital world of children and young people. The project was developed to inform the European Commission and create policies aimed at safer Internet use by children and young people. Furthermore, the project showed that the Internet is integrated into these users’ lives, providing various services (such as doing homework, watching video clips, and sending instant messages, among others). From research conducted between 2006 and 2015, in which researchers from 25 European countries (including Portugal) were involved in collecting empirical data on the use that children and young people (9–16 years old) make of the Internet [

29], the national results show that these users access this platform very often, and increasingly early.

Moreover, they are the ones accessing the Internet from their laptop computer the most. The national policies implemented between 2008 and 2011 in Portugal are seen as the leading cause. Moreover, the democratization of early Internet access may have contributed to the fact that the first use of the network by children up to 10 years old is, on average, among the highest in the European context [

30].

However, we emphasize that the evidence on children’s early access to computers and the Internet does not necessarily imply that the practices are homogeneous, or that these users have equal skills in working with these tools. For this reason, we believe that research must incorporate a set of personal and sociodemographic variables that may have implications for access practices and online consumption.

3. The Internet and Digital Platforms in Young People’s Lives

Within the field of Communication Sciences, in research developed in recent years on the relationship between young people and the Internet and digital platforms, there are different ways of approaching the subject. On the one hand, there are the studies closer to a mediacentric approach that emphasizes the Internet and—on the media and digital platforms—delegating to a secondary place the users’ agency and their life contexts as if these had little or no connection with the uses and meanings that are drawn from the experience with the media [

24]. On the other hand, socio-centric research focuses on understanding the nature of interactions by considering a set of variables besides personal, social, and cultural circumstances [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. From this perspective—and in particular, regarding Internet access and use of this tool—studies show that although access and use are widespread among younger people, the same cannot be said about the modes of service and experiences, as they are affected by a set of variables and circumstances, from the social origin and family morphology to the gender and age of users [

2]. The authors assume that users’ needs, preferences, acquired values and customs are also fundamental to this involvement.

In recent decades, there have been a growing number of studies on access to the Internet and social media and the nature of the uses of these tools [

30,

35,

36,

37,

38]. The Pew Research Center, a research and information center on behaviors, attitudes, and trends in the life of American society and the world, periodically provides data on media use. In a report published on 1 March 2018 [

39], on the uses of the Internet and social media by American young adults (18–24 years old), Snapchat, Instagram, and Twitter were pointed out as the most popular platforms for this group, being accessed daily, and at various times, mainly through mobile devices. Of these, 51% admit they would have difficulty giving up these platforms, which decreases as the users’ age increases, indicating a predisposition for less dependence. In another report from April 30 of the same year [

40], with the same age group, on the impact of the Internet and social media on society, the users provided positive feedback regarding the presence of these platforms in their lives and the general context of society. Of these, there is a tendency for those with higher education qualifications to consider that the Internet impacts society positively. The reasons are mainly the ease and speed of access to information and the possibility of connecting with family and friends through digital platforms.

Overall, the younger generations have more Internet access than previous generations. Of those, young adults with qualifications are more likely to access the Web and to prefer digital platforms as part of their daily lives compared to those with lower qualification levels [

41,

42]. These generational differences also stand out regarding the types of use and preferences regarding digital media, with young adults favoring social media platforms.

Although the use of the network is part of the daily life of young people, particularly in developed societies, it should be noted that this can translate into a set of practices with implications for socialization and cultures. This also results in negative consequences for the lives of these users when used in excess and in an unaware manner. Amaral et al. [

28] (p. 128) speak of an “umbilical relationship between digital consumption and socially structuring practices for the formation of a youth culture”.

In recent decades, there has been a growing number of studies that have pointed to the potential damage caused by Internet addiction [

12,

15,

17,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48], alerting us to the importance of studying and preventing the consequences that can arise from excessive and addictive Internet use. Such studies have defined addiction from a behavioral point of view, based on man–machine interaction, passive or active, that can be considered excessive [

49]. Such behavior interferes with daily life, bringing consequences to health such as sleep problems, increased levels of anxiety, stress, depression, and low self-esteem—these end up affecting family, social, and professional relationships [

50,

51]. In this regard, empirical studies on Internet addiction highlight the impact of these factors on the performance of essential functions in school and work settings, leading to a significant reduction in academic and professional success rates [

52]. Although there is consensus around the associated risks of compulsive online behavior, Internet addiction is not unanimously recognized within academia [

53]. Controversies still exist regarding the factors at the genesis of the addiction, the elements that compose it, and its path [

54].

Likewise, Internet addiction presents different typologies, sub-typologies and nuances, making it difficult to standardize the research [

55]. At the national level, research on the subject is still poorly developed compared to the international panorama, focusing mainly on social media and online videogames [

2,

56]. However, studies have shown that—despite affecting a small percentage of individuals—Internet addiction is a reality that, in Portugal, mainly affects teenagers and young adults in school and university, thus requiring intervention and the prevention of addictive behaviors in these contexts [

43,

57].

In this sense, the pandemic context in which we live carries increased risks for young people who have seen their freedom and sociability become limited to their homes and dependent on the online world. Several studies at the international level have crossed the field of psychology and communication to analyze possible changes in media use during the pandemic, focusing on the potential consequences of excess or a lack of quality [

12,

14,

15,

17,

45,

57,

58]. Although these were sometimes preliminary studies of an ongoing phenomenon, they allow us to identify risk factors and issues that require attention and long-term investigation by the academic community and public health authorities. Faced with the dissemination of the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, the containment measures taken by world authorities involved physical isolation, distancing, quarantine, and remote work. Such efforts, prolonged in time and sometimes with no end in sight, led several international organizations to warn of the potential negative impacts on physical and mental health, with the risk of exacerbating already existing issues [

59,

60]. Indeed, recent studies state that extended confinement at home endorses reduced levels of physical activity, exposure to daylight, and social contact, in turn provoking increased levels of stress, feelings of uncertainty and control, and an inability to engage in rewarding leisure activities [

61,

62,

63]. At the same time, it favors greater media consumption, namely of social media, platforms that allow the mitigation of the effects of isolation, whether for informational and recreational purposes or to cope with feelings of loneliness and anxiety [

14,

64].

It is also important to note that, during the pandemic, we watched the attempt to transition to distance learning all over the globe. However, in many countries, teachers, students and universities were not prepared for such developments from technological and pedagogical perspectives [

65]. In fact, until 2019, in general, distance learning took place only in specific situations and with different audiences [

66].

An ever-increasing number of studies argued that teaching and learning in an online environment are very similar to education and learning in traditional classes [

67,

68,

69]. They claim that online classes can be as effective as face-to-face classes, but only if they are well designed, implying technical, administrative, and pedagogical competencies. Besides this, as stated by distance education specialist Marguerite Koole, today, we know that many aspects must be considered in the transition from face-to-face to online learning, such as differences in space, social presence, self-presentation through technologies, and interaction patterns [

70]. In addition, we must consider that some characteristics of distance learning may increase feelings of frustration and stress, such as limited internet access, the lack of face-to-face interactions, and motivation [

66]. Since the COVID-19 pandemic reconfigured physical and social interaction, “(…) students may feel invisible, excluded, even when participating via online technologies, and the designs of learning activities must take this into consideration, especially during social distancing, when isolation affects all students, regardless of age” [

65] (p. 456).

An international quantitative study that aimed to evaluate internet addiction during the pandemic [

45] carried on with 2749 university students from seven countries (The Dominican Republic, Egypt, Guyana, India, Mexico, Pakistan and Sudan) found a direct relationship between the pandemic and internet addiction, with a significant manifestation in sleeping disorders. Moreover, the same study found that the university sector, smoking history, and health status were significant predictors of Internet addiction. It should also be noted that male participants scored higher on Internet addiction when compared to adults and female participants. Participants with a smoking history and self-reported poor health scored higher on Internet addiction.

Another piece of research carried out with students attending university education in Spain by Gómez-Galán et al. [

12] showed a high consumption of social networks during the pandemic, with significant incidences of addiction. The study used a descriptive and quantitative methodology to understand the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on excessive Internet use. The results show numerous interconnected variables in the analysis of social network addiction. The fact that addiction to any of the factors on the applied subscale influences the rest of the elements is noteworthy. However, “Lack of personal control in social networks” and “Excessive use of social networks” are the most relevant data. Furthermore, it has been shown that there is a link between different addictions, with the diagnostic criteria being the same for both substance addiction and addiction without substances. Concerning the excessive use of social networks, the type of knowledge and age are the leading causes.

Thus, if a pandemic involves emotional and social problems through a reshaping of routines and relational dynamics, teenagers and young adults—who are the most dependent on social contact with peers—may find themselves in a position of greater risk to physical and mental health. In this context, and given the scarcity of studies at a national level, researching the media uses and practices of Portuguese youth in a pandemic context is an urgent matter [

71].

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Social Habits and Media Practices

One of the aspects referred to in the questionnaire survey sought to assess activities integrated into the leisure time of the respondents, with particular emphasis on the place of the Internet and conventional media, such as television, radio, newspapers, books, and videogame consoles.

Regarding conventional media, the data allow us to perceive that the newspaper is the medium with which the interviewees spend less time. That, among the range of other media they have at their disposal, is the one that least integrates their preferences, followed, in increasing order, by videogame consoles, books, radio, television, computers with Internet access, and smartphones with Internet access. Female respondents consume more television, but the difference gets smaller as viewing time increases (to more than three hours).

Female respondents read newspapers less than male respondents. Men listen to the radio less than women, who listen for more than 1 h and between 2 and 3 h. The videogame console is the medium consumed for more time by the respondents, with most women only doing so for short periods, i.e., less than 30 min. The time spent with books is significant among female respondents. The time spent on the computer without the Internet is practically equal. As for computers with the Internet, women stand out in terms of time spent on them, providing more data above the three-hour mark. Finally, as for cell phones/smartphones, women dominate at all intervals, with men standing out when consuming them for over three hours.

Internet consumption is thus the most significant media-related activity in the respondents’ daily lives. In addition to being—compared to the other media listed—the only one that meets consensus among all of the respondents, who admit that they access this tool every day (99.8%), it is the one with which they spend the most time. This tool is mainly used to carry out academic work, connect to social media, and socialize. There is a clear preference among females for these online activities compared to males.

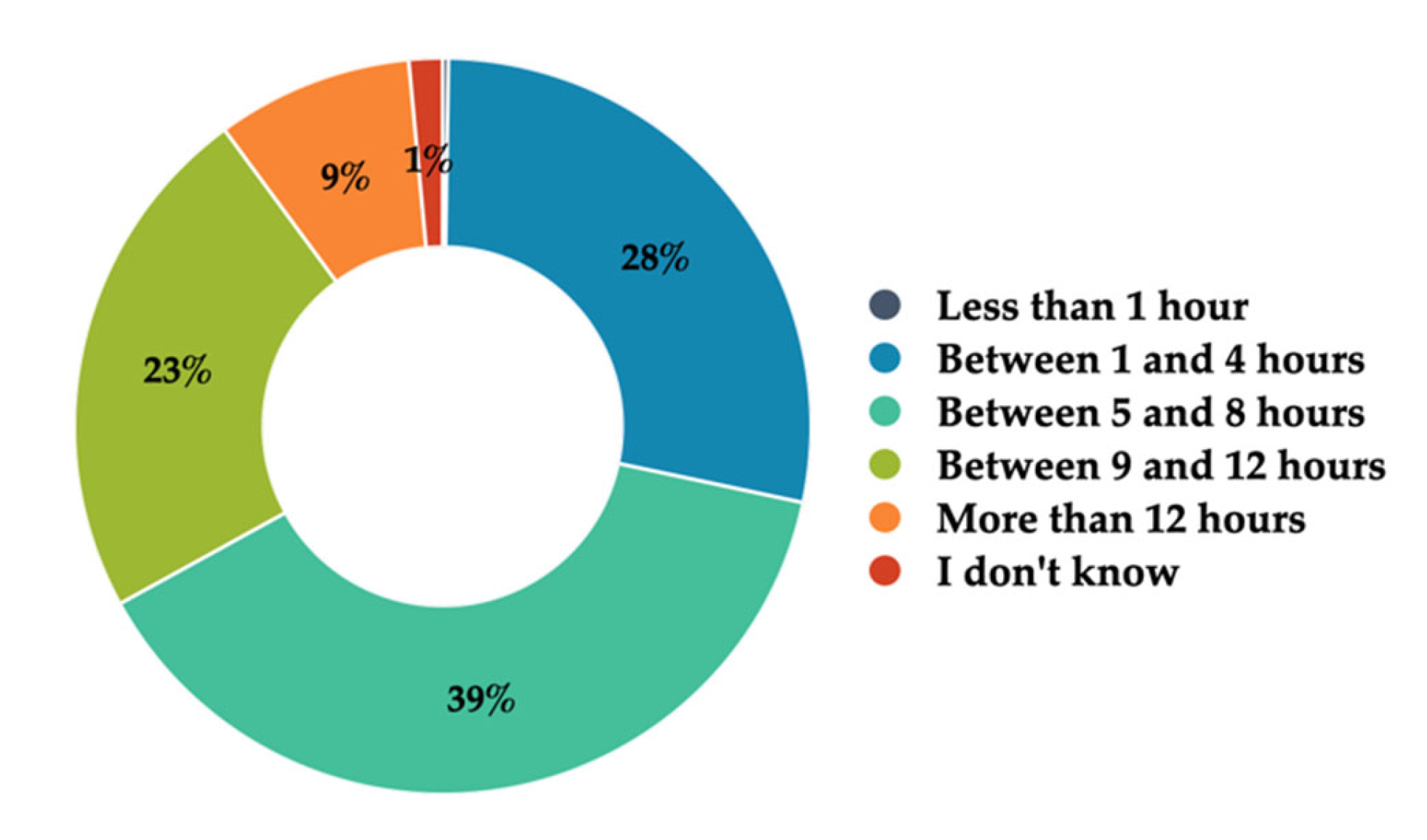

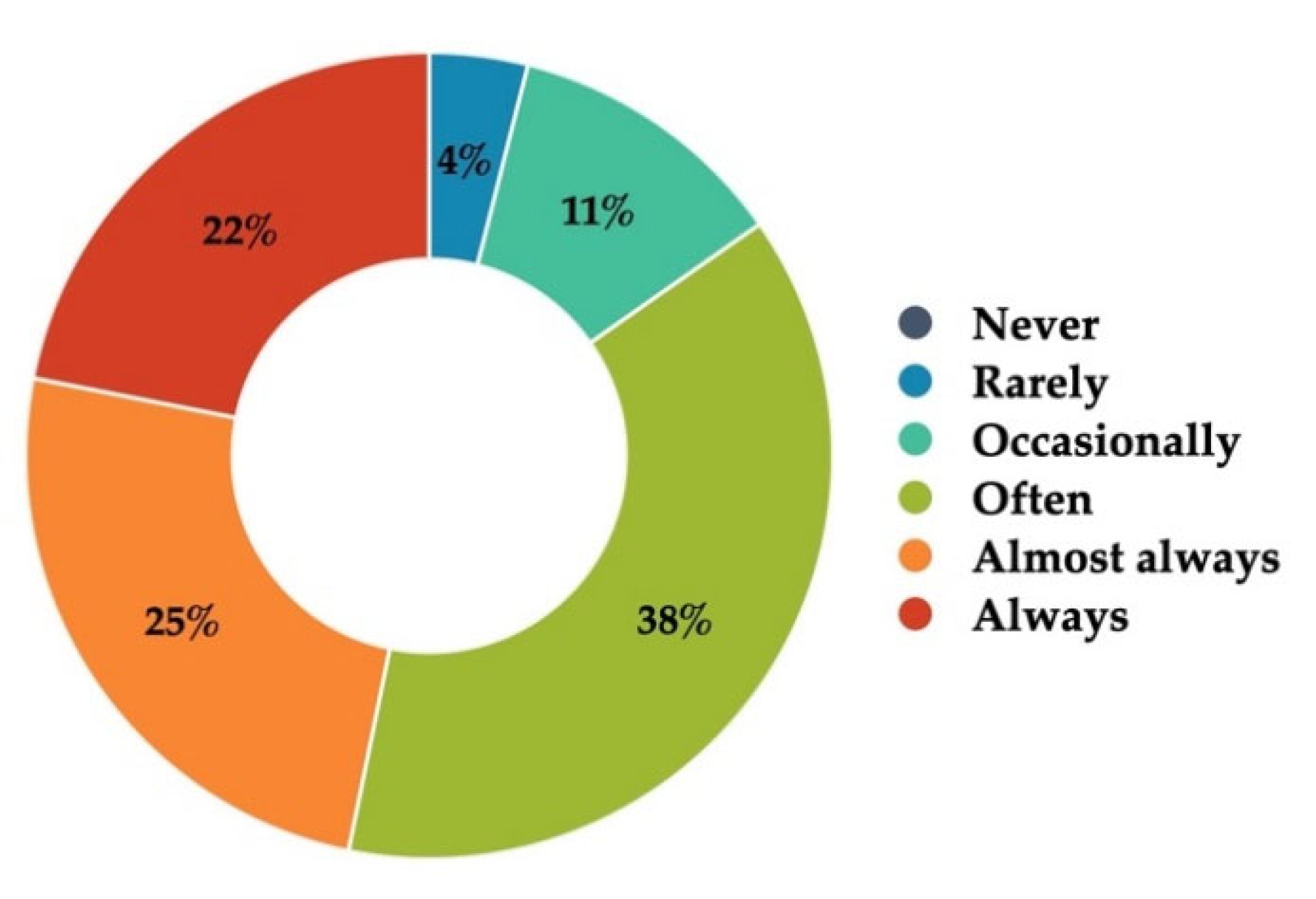

The data presented show that the percentage of the respondents who admit to spending more than five hours a day on the Internet is surprising; notably, 9% of the respondents say they spend more than 12 h online (

Figure 1). These first data on time spent online are interesting because they help us to understand how the pandemic has transformed the routines of students themselves, contributing to an increase in the number of hours spent online, especially compared to what happened before the pandemic, as indicated by some of the studies carried out [

14,

15,

16,

17,

74,

75].

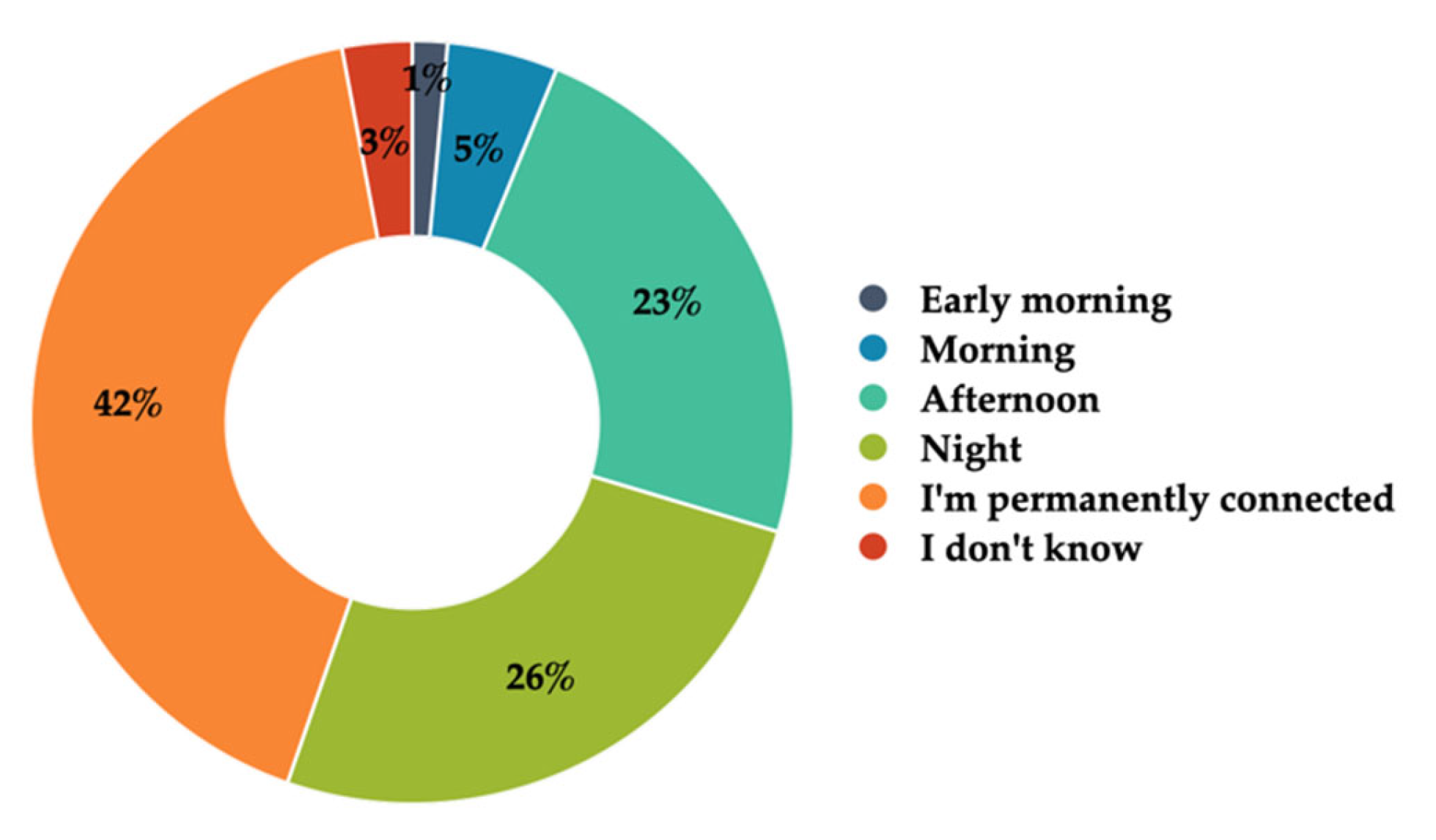

Of the 407 young adults surveyed, 42% admit to being permanently connected, as shown in

Figure 2. The smartphone is the preferred device through which respondents access the Internet (74.7%), followed by the laptop (15.7%), the desktop at home (8.6%), the tablet (0.7%, corresponding to three respondents), and the desktop at the educational institution (0.2%, corresponding to one respondent).

We can observe that in terms of time spent online, the women from our sample declare spending more time than men, with 29.5% spending 5 to 8 h, whilst the male respondents’ majority is at 10.3% in the 1 to 4 h per day slot (

Table 3). Moreover, we can also see that those female respondents declare spending more hours online than their male counterparts. The second category answered by women was 9 to 12 h, while the male respondents’ second most answered category was between 5 and 8 h. Both the males and females of the sample do not particularly distinguish a time of day in which they are connected, as most of the females (32.7%) and males (8.6%) of our sample declare that they are constantly online. For both genders in our sample, we can also observe that the second time of the day these respondents spend online is the afternoon (17.2% females and 8.4% males).

Regarding offline activities, such as playing sports, chatting with friends, hanging out with family members, listening to music, travelling, and going to shows, the preferences are for hanging out with friends and listening to music. In total, 40% of young adults admit to hanging out and talking with friends often, and 21% do it daily. In total, 57% of the respondents admit to listening to music every day. However, the percentage of the respondents who mention walking around and hanging out with friends and family relatively often during the pandemic is surprising (

Figure 3). The responses of the young people surveyed show some changes in offline activities, which is not surprising considering that quarantines and curfews multiplied during 2021, and many outdoor activities were limited [

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, it is interesting to note that some activities are dominant among young people, such as listening to music, a daily practice, which, according to a report by one of the leading players in the area of sound, is increasingly emerging as a form of stress relief. According to data from Culture Next, Spotify Advertising’s annual study, in 2021, 71% of Gen Zs used audio to reduce stress levels. Among millennials, there is also the idea that audio can help promote mental health [

76]. In this context, it is essential to highlight the growth in the consumption of podcasts [

59], which can help explain young people’s responses.

The data obtained allow us to verify that being on the Internet is the most significant media-related activity in the respondents’ daily lives, together with other activities such as being with friends and listening to music. The everyday life of the young university students in the survey seems to be mainly organized according to actions that gratify them and align with their personal choices and preferences.

It should also be noted that the main reasons for using the Internet, in order of importance, are, for the female respondents, the following: to pass the time/escapism; to search for information on personal/professional matters, to carry out research on curiosities, to do academic work, and to access social media. The respondents’ reasons are as follows, also in order of importance: spending time/escapism, researching information on personal/professional matters, researching curiosities, doing academic work, and accessing social media. It is essential to highlight that the Internet is decisive in the occupation of time for young people during confinement, which justifies the concern identified in the various studies that carried out similar analyses and made psychological wellbeing depend on this permanent connection [

12,

15,

17,

45,

75]. The fact that they remain locked for longer has increased the time they spend online, along with new signs of potential dependence, such as sleep disturbances or anxiety, as we will see later.

5.2. Routines and Online Consumption

In line with the data mentioned in the previous topic, another question asked is related to the association between the pandemic and the frequency of Internet use, with 88.0% of the respondents admitting that it increased during the pandemic period, mainly due to its relevance in the context of academic activities in lockdown periods. However, 2.9% of young adults acknowledge not knowing if there was, in fact, an increase. In total, 60% even consider that using the Internet has become more indispensable since the pandemic’s beginning, although 30.2% mention that it is just as necessary.

When we inquired about the possible increase in their internet consumption during the pandemic, all of the respondents, including those who preferred not to identify their gender, agreed on such an increase (88% of the sample). On the other hand, the distribution across categories in each gender is also similar in terms of their need for internet consumption since the beginning of the pandemic, with both female and male respondents deeming the Internet more indispensable (61% of the sample), and in second place, choosing “same as before” as an option (30% of the total sample) (

Table 4). Moreover, all of the genders also agree that the pandemic made them more internet-dependent, with more than 65% of the total sample agreeing with that idea, against less than 23% of the sample denying it.

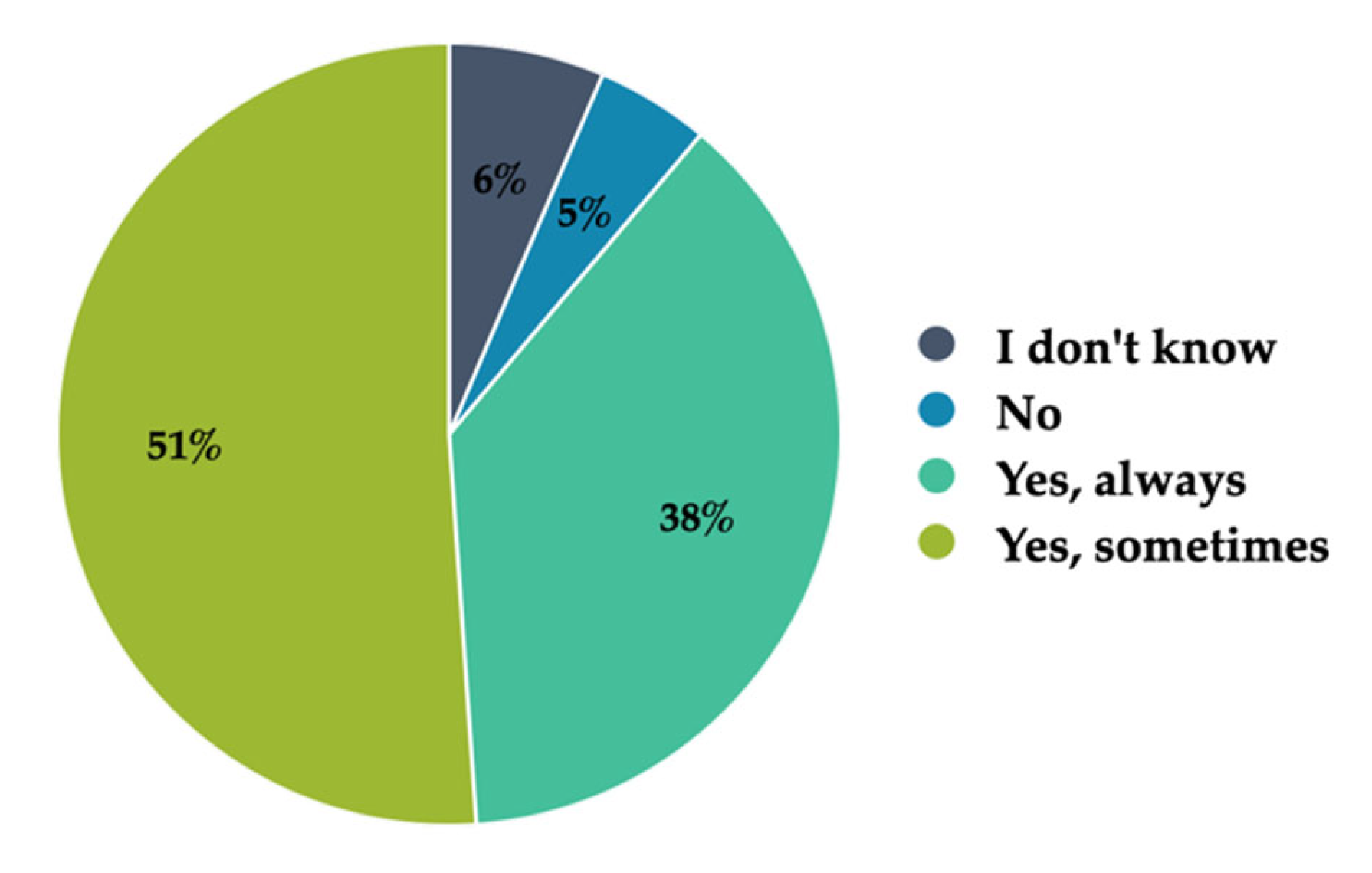

However, it should be noted that 38% consider that the Internet is always essential to their lives. In comparison, 51% stress that it is necessary on some occasions, as shown in

Figure 4. Although most students believe that the Internet played a decisive role during confinement, it is vital to highlight the percentage of the respondents who think that it is essential in their lives. These responses are not directly related to its use during the pandemic but rather as something more permanent, without which the students’ lives would not be the same, which helps to explain the preoccupation in terms of dependence [

12,

14,

15,

17,

45,

61]. These answers also allow us to understand that the pandemic has only worsened a situation that had already occurred previously. Thus, we can understand how important it is to find solutions that help solve Internet addiction, which is a more structural problem.

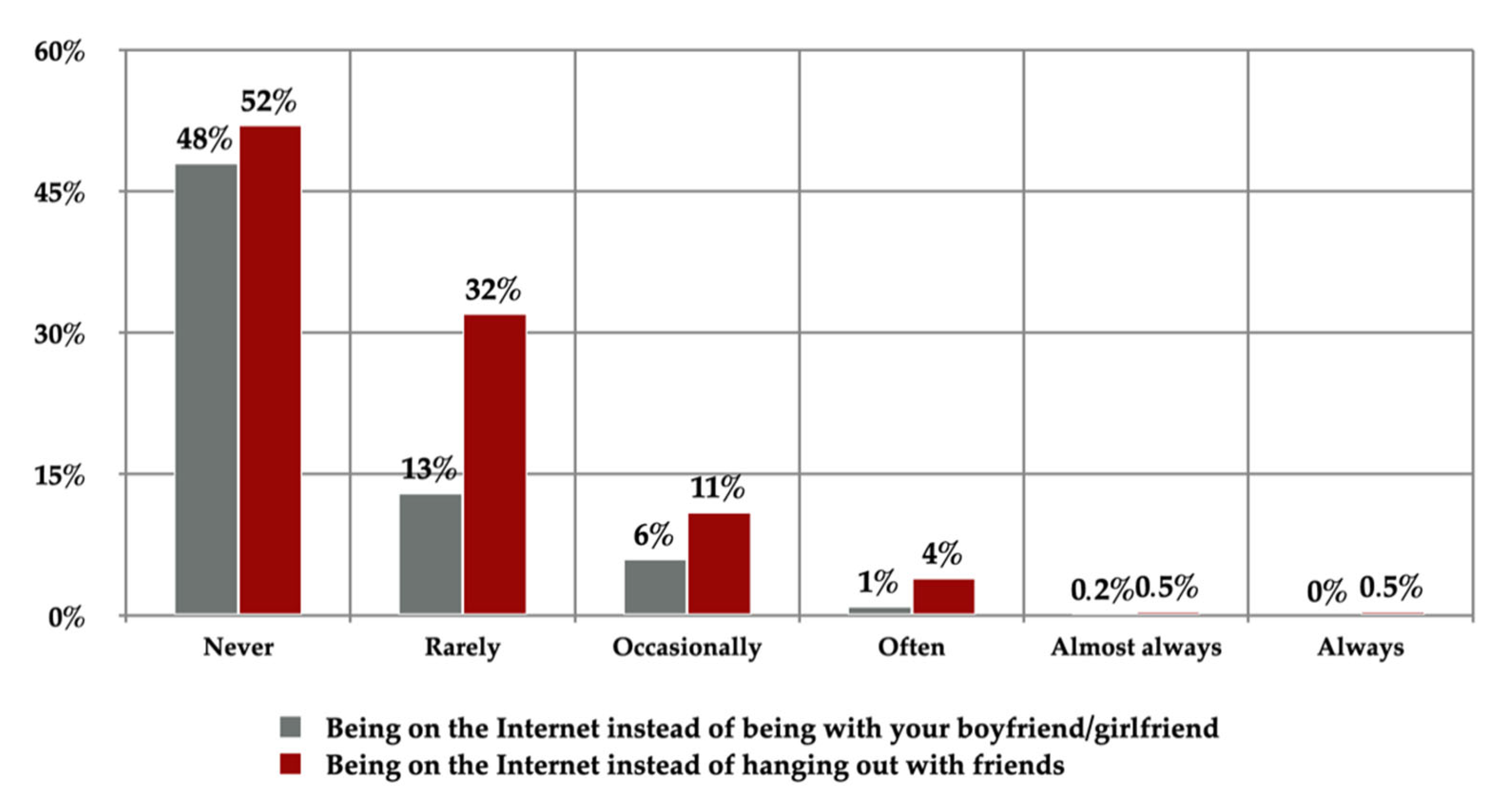

The primary occasions pointed out by both genders where the Internet is indispensable is at work and in academic life. Women are the ones who consider that the Internet has become more vital since the beginning of the pandemic, and men are the ones who think it has remained the same. This indispensability aspect is evident when being on the Internet becomes a preferential activity compared to other activities, such as being with a partner or friends, as some respondents, particularly males, admit. In this regard, even though 31.4% of the young adults surveyed are not in a romantic relationship, of those who are, and even a not very significant percentage (6.4%), admit that they occasionally prefer to be on the Internet than with their partner. The same applies to being with friends (see

Figure 5). Although the percentage is low, these data point to other symptoms that end up being associated with Internet addiction, such as a lack of self-esteem, or even depression [

55,

75].

In total, 48% of the respondents state that they never prefer to replace the company of their boyfriend/girlfriend with Internet consumption, and 52% mention the same about friends. However, the data presented show that, for some respondents, being on the Internet may replace the relevance of expressive relationships with those with whom they maintain a close relationship.

It should be noted, however, that the creation of new online friendships does not seem to be significant for the majority of the respondents (23.8% never create new relationships, and 41.0% do it rarely), although 24.6% admit to meeting new online friends occasionally, and 7.4% do it frequently. In total, 2.2%, corresponding to nine respondents, recognize that they almost always establish these new relationships, and two respondents admit to always doing it.

Another relevant data point shows the priority of accessing social media and e-mail in favor of other activities. In total, 37.8% of the respondents admit that they frequently access these media before performing other tasks, 24.8% assume they do it almost constantly, and 21.9% say they always do it, as shown in

Figure 6.

5.3. The Pandemic and Online Dependency

In the previous topic, questions related to routines associated with Internet access and use were addressed, focusing on the pandemic period. We now intend to identify and understand how these online practices and access habits affect the respondents’ Internet addiction and lifestyles. The results arising from the question about how often respondents notice that they have been online for too long reveal that there seems to be some awareness that the time spent on the Internet is excessive, as shown in

Figure 7, as there is a significant percentage of young adults who often and occasionally notice that they have been online for too long.

The data collected are in line with other studies that also identified an increase in online time during the pandemic, and sometimes a lack of perception about staying connected [

75]. On the other hand, the students’ answers also highlight the importance of the people around them, namely parents, in drawing attention to and regulating their time online [

75,

77]. However, despite the perception of excessive time being spent online, it should be noted that only 22% of the respondents state that others occasionally question them due to the time they spent on the Internet. In total, 7% admit that this happens frequently; 2% of the respondents, state that it occurs almost constantly, while 1% states that they are continually questioned due to this. In total, 39% of the respondents admit to it rarely being called to attention, and 29% mention that they are never asked.

The sample was also asked about their general awareness of their relationship with the online, with 51% of both genders agreeing that the internet is sometimes indispensable for them, leaving less than 5% of the sample to disagree with that statement. Interestingly, female respondents declare, at 23%, that they often realize they have been online for too long, whilst the males’ higher percentage corresponds to “occasionally”, with 12% (

Table 5).

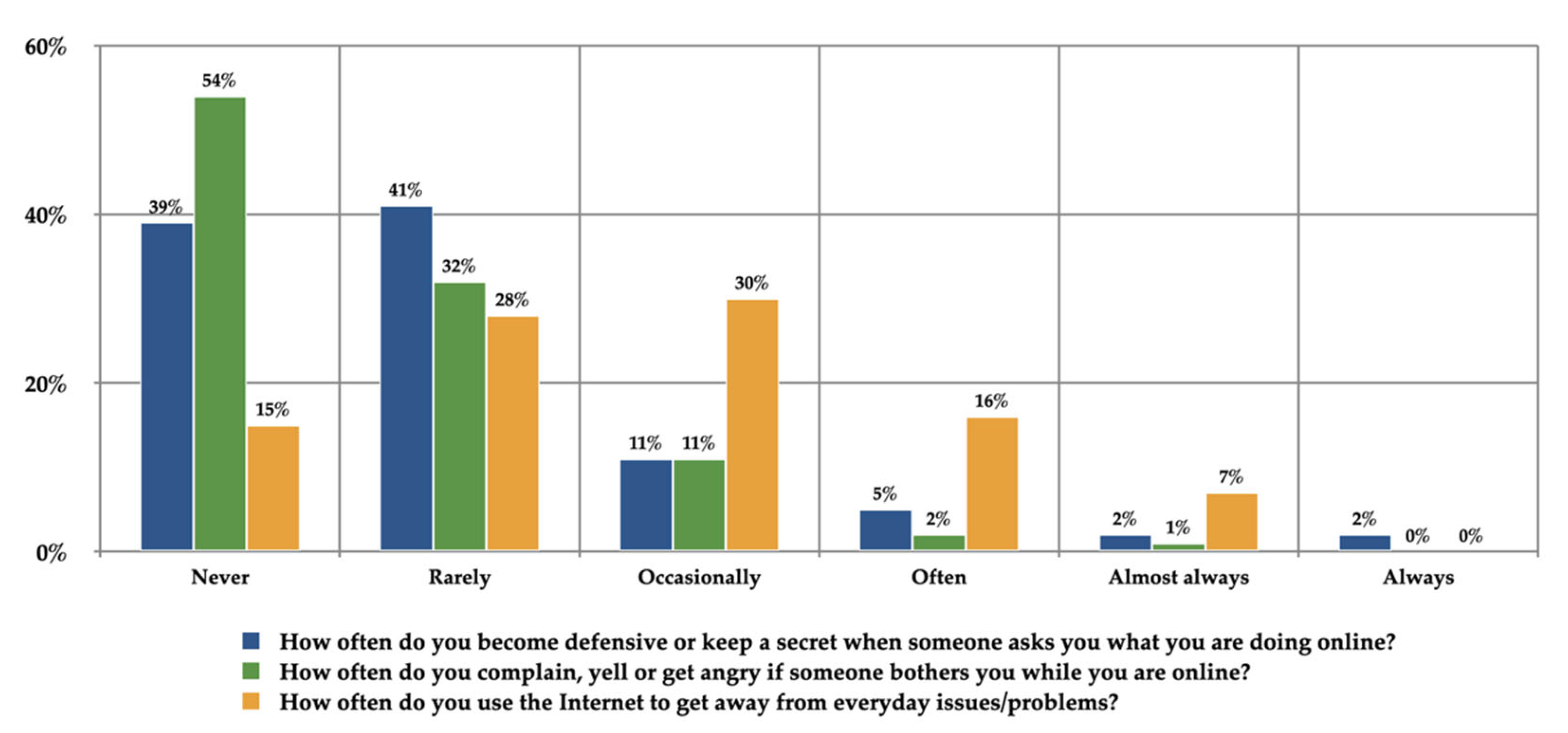

The data also show that the percentage of young adults who have a defensive attitude or hide what they are doing online when asked about their activities is not very significant, as seen in

Figure 8.

Regarding the question “How often do you complain or get irritated when you are online and are bothered?”, 54% of the respondents say that they never complain or get irritated; 32% do it rarely; 11% assume they do it occasionally; 2% do it frequently; 1%, assume they do it almost constantly, and one respondent does it consistently.

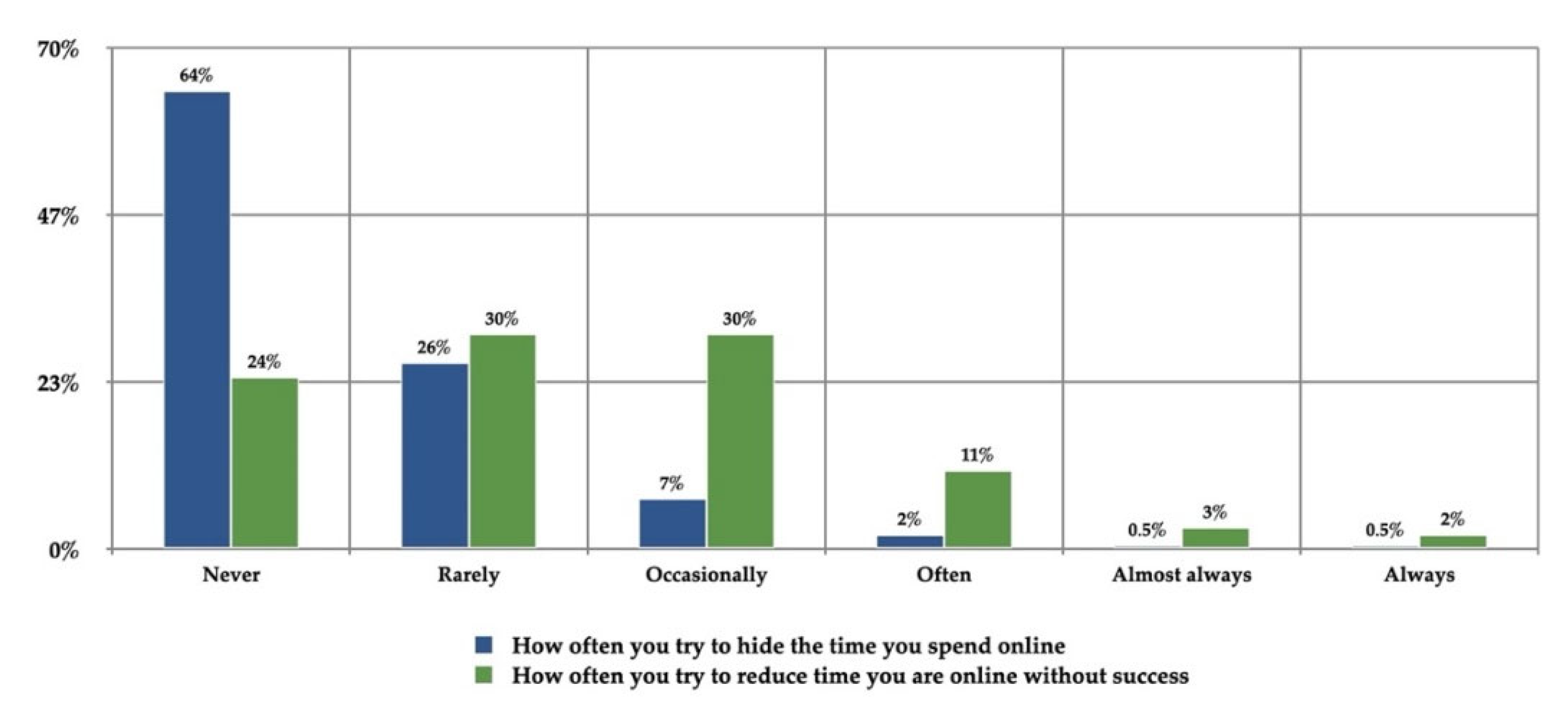

The data from the questionnaire survey revealed that even though some respondents make an effort, albeit unsuccessfully, to reduce the amount of time they spend online (

Figure 9), 64% assume that they never try to hide the amount of time they spend online.

Also significant is the percentage of the respondents (33.7%), particularly males, who assume that their academic performance is impaired due to the amount of time they spend online. Although this is a minority, compared to the percentage of the respondents (65.8%) who say that their academic performance is not hindered because of their time spent on the Internet, it is still a remarkable figure. In line with previous studies, these data also highlight the importance of reflecting on the relationship between time spent online and academic success [

52]. This problem, which emerged before the COVID-19 pandemic, gained new contours to be discussed during quarantine and curfews because—whilst closed at home—the Internet became essential in order for students to attend online classes. However, this is also the moment to look at this data and think about how we can balance Internet use in contexts like the one we live during the pandemic, in which the online is vital for distance education [

65,

75].

Students were also asked about their efforts in reducing their online consumption and hiding such consumption from their entourage. For female respondents, the highest category was “rarely” (22%), considering their attempts to reduce their consumption, and “occasionally” for males (9%). As for the second topic, respondents majorly agreed that they never try to hide their online consumption, with 64% denying any hiding across the sample (

Table 6).

Regarding the perception of the health consequences of excessive online consumption and the feelings associated with it, among the various questions asked, the most significant results obtained relate to the implication of excessive online use, especially at night, on sleep quality. According to the results obtained, it is assumed that there is an association between online consumption and sleep disorders for almost half of the young adults surveyed. In total, 23.8% of the respondents acknowledge that they suffer from this disorder occasionally; 18.7% admit that they suffer from it frequently; 5.4% of the young adults suffer from it almost always; and 1.2%, corresponding to five respondents, reveal that constant access to the Internet always has an impact on their sleep disorders. In total, 27.5% indicate that their sleep is rarely disturbed due to excessive Internet access, while 23.1% assume that this never happens. These data also confirm results from studies made in other contexts, and alert us to a relationship between the time young people spent connected during the pandemic and their sleep problems [

45,

64].

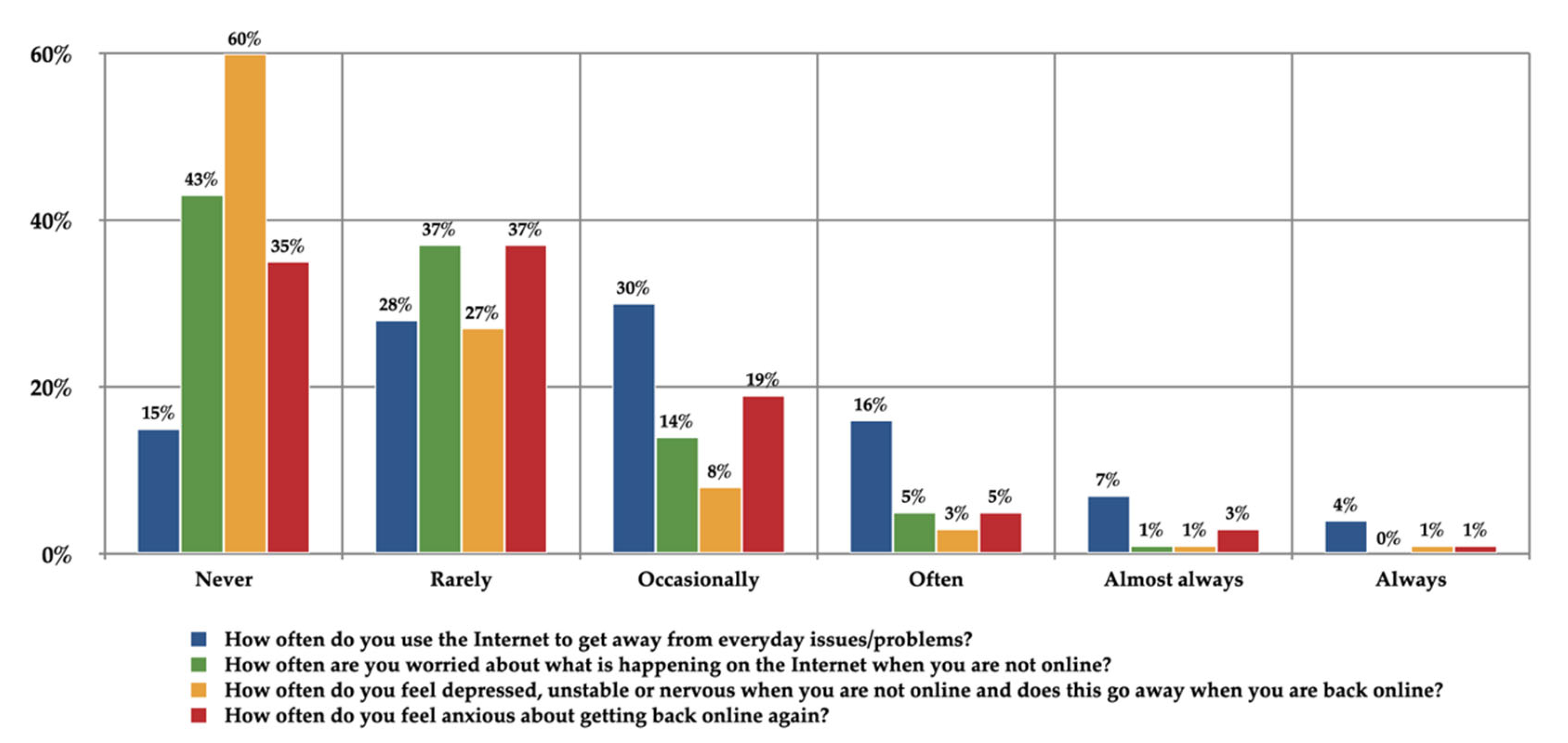

Although it is less expressive than the results mentioned above, it is noteworthy that the respondents admit that they experience negative feelings and adverse emotional reactions, such as instability and nervousness, when they are not online. In this regard, when confronted with the question “How often do you feel depressed, unstable, and nervous when you are not online and feel good again when you are back online?”, the data obtained show that the majority (60.4%) of the respondents never experience the listed feelings. However, it is noteworthy that young adults admit to feeling adverse emotional reactions when they are not connected, with greater relevance in the case of women (

Figure 10).

The results also show that the percentage of the respondents who assume that the Internet is a means of escape from everyday life is similar to that of the respondents who do not consider it.

In this regard, as shown in

Figure 10, the data obtained also show that 5% of the respondents, with a higher incidence of female respondents, admit feeling frequently anxious until they go back online; 19% experience that feeling occasionally; 3% realize feeling worried about being offline; and 1% recognize that they always feel anxious.

It should also be noted that although the percentage of the respondents who reveal feeling worried about what is happening online when they are not connected is not statistically significant, 14% admit to feeling this concern occasionally; 5% assume feeling it often; 1% mention that this concern manifests itself almost always.

Although, according to the results presented, online consumption may have less positive consequences for the daily life of the respondents, for example, in terms of sleep disorders and experiencing adverse emotional reactions, the results of the questionnaire survey show that a higher percentage of the respondents consider that using the Internet has more advantages than disadvantages. On the other hand, most of the respondents believe that the benefits and advantages of the Internet are equal.

Deeper into the survey, students were also asked if their academic performance could be impacted by the time spent online. The vast majority of the sample disagreed with this idea (66%), whilst only one-third (33%) agreed that their internet consumption impacted their academic performance.

As for the consequences that may result from excessive internet use, the first category chosen by female respondents was “real-life social isolation” (29%) and more excellent knowledge and acquisition of information by their male counterparts (12%). We can observe a more positively inclined view of such consequences by men, although the same category reached second place for female respondents (28%) (

Table 7).

In order of relevance, we can also highlight the consequences of excessive Internet use for female respondents: social isolation, increased acquisition of knowledge and information, and addiction to social media. The same results for male respondents highlight the following consequences in order of relevance: acquisition of knowledge and information, isolation, and addiction to social media. In order to understand these results, we must consider that—in a pandemic context—students feel that there are many advantages, namely following online classes and socialising in isolation. However, it is also essential to highlight the perception of the potential isolation caused by addiction to the Internet [

12,

14,

61,

62,

63,

64].

6. Conclusions

The data collected allow us to perceive that the Internet is a fundamental element in the daily life of the respondents, with this importance intensifying during the pandemic. This may be because, during the pandemic period, when the data collection took place, long periods of lockdown were experienced, forcing the population to remain inside their homes, thus reducing the possibility of travelling to outdoor spaces and carrying out activities in the offline world. On the other hand, it should be noted that during this period, the model of online education and remote work was adopted so that the respondents’ academic and, in some cases, work activities took place over the Internet, as demonstrated by the results obtained. Alongside this consumption, it should be noted that during the pandemic period, there was also an intensification of dependence on the online, as demonstrated by the 65.8% of the respondents who assumed that the pandemic made them more dependent on the Internet, with particular prevalence in the case of female respondents.

We conclude, therefore, that during the pandemic period, the access to, time of use of, and dependence on the Internet intensified. These data become more worrying when it is verified that online consumption interferes with the health of users, namely in terms of sleep disorders and the experience of adverse emotional reactions—such as instabilities, depression, and nervousness—when not online, which dissipate when connected once again.

Internet access is achieved through smartphones daily, especially at night, as this is a privileged leisure time for respondents in their professional and academic activities during the day. Instagram and WhatsApp are the preferred social media for these users, a data point which is in line with other international studies [

66,

67]. It can even be mentioned that the priority given to access to social media and email, to the detriment of activities in the offline world, was visible in the results obtained. There is even priority in accessing these platforms, to the detriment of other activities such as watching television, playing sports, being with friends and family, listening to music, travelling, or going to shows. We recall, in this sense, that 37.8% of young adults assumed that they often access the Internet before doing other activities, and 21.9% even thought that they do it all the time.

In this sense, specifically concerning expressive relationships, there is a conclusion that reveals that there were those who assume that, occasionally, they prefer to be online than with their friends and partner, especially in the case of male respondents. This is surprising data, showing that being on the Internet is, for some respondents, more relevant than being in the company of people with whom they have built a relationship.

Despite the interference of the Internet in daily life—which, for almost all of the young adults surveyed, is seen as a form of escape—at the same time, there is the perception that its consumption may result in less favorable effects on the personal life of individuals. However, significant numbers show an attempt to spend less time online and a specific awareness that the time spent online can be excessive. The respondents reported that, sometimes, they notice that they have been online for too long. However, only a tiny percentage of the surveyed users admitted that attention is called to this by others due to their time on the Internet.

Despite the less-positive effects of Internet use, more respondents associated the Internet use with advantages than disadvantages. More significant was the percentage of the respondents recognizing that the advantages and disadvantages of online consumption are similar.

7. Limitations and Paths for Further Research

This research had some limitations, such as the small size of the study group, which was constituted by a convenience sample of undergraduate students from Lisbon and the Beira Interior regions. The subjectivity of the respondents in the online self-report survey represents another critical point once the data collected are subject to method biases. The type of analysis conducted, basically descriptive, can also be considered a limitation. Nevertheless, the objective was to obtain a first reading of the data, not proceeding to inferential analyses, correlations or the application of other statistical tests, as it is not our goal to infer results from the sample to the population.

However, and although the results obtained are not representative of students attending higher education institutions in Portugal, the issues presented and discussed in this exploratory article emphasize the need to develop more studies on the theme of Internet addiction, with particular emphasis on the younger generations for whom the online world is not only an essential element of their daily life and leisure time but also integrates a set of socialization agents, with particular relevance for the way social representations about the world are developed. At this level, there is a problem evident in this article and other relevant studies in the areas of psychology and medicine, which concerns the consequences that excessive Internet use can have on young people’s physical and mental health.

We also emphasize the need for communication studies to incorporate this theme, making itself more robust in this area of knowledge, contributing to a field of analysis that makes visible a holistic approach with repercussions for the transfer of knowledge between academia and society, with relevance to the life contexts of the youngest. The studies of audiences and media and digital literacy constitute an approach of particular significance by incorporating not only scientific knowledge about the nature of the appropriation of online contexts by the younger generations but also by designing strategies that are effective in the development of skills that allow these users to maximize the benefits and minimize the harms arising from the use of these media, thereby embodying a more critical and healthy relationship, enhancing the positive side of these platforms. This is a relevant issue, especially in cases like the COVID-19 pandemic. This can intensify the risks related to the Internet and digital technologies.