Standing Up for Culturally Competent Care in Portugal: The Experience of a “Health in Equality” Online Training Program on Individual and Cultural Diversity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Model

1.2. Intersectionality Framework

2. Training Design

2.1. Training Goals and Objectives

- To evaluate primary health care professionals’ satisfaction with the training sessions.

- To present a critical evaluation of the training program by both trainees and trainers in order to gain knowledge on the degree of achievement of its objectives and on the training process.

2.2. Training Participants

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

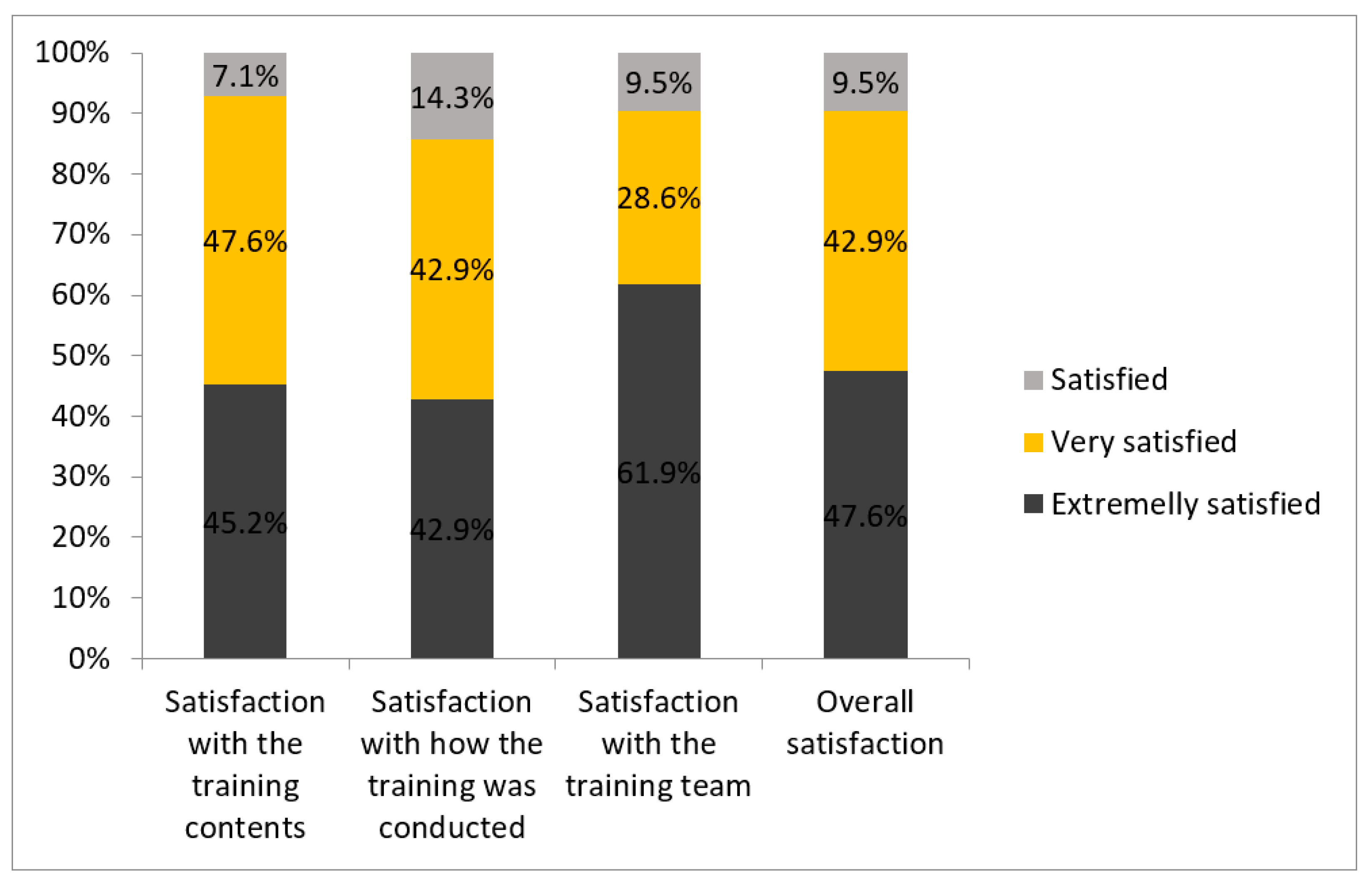

3.1. Trainees’ Satisfaction Evaluation

3.2. Critical Reflection of the Training Program

3.2.1. Quality of the Training Contents

“Appropriation of new concepts, becoming aware of new views. A more systemic view of the person.”(Trainee 4)

“The relevance of the training contents since it is still a taboo subject in society.”(Trainee 5)

“In general, I liked all the topics and I consider them all very useful for both my personal and professional training.”(Trainee 6)

“The clarification of concepts of the various areas. The training provided me with vocabulary, understanding, and resources.”(Trainee 23)

“All topics added knowledge that I can apply in my daily practice.”(Trainee 28)

“The intersectionality of themes allowed for a global, transversal and multiple learning experience regarding health intervention with different stigmatized people and groups.”(Trainer 1)

“The proposal of the very rich and complementary training modules and the consistency with the perspective of intersectionality.”(Trainer 2)

3.2.2. Quality of the Trainers

“The questioning, restlessness and internal reflection (potentially generating change) that was motivated/triggered and widely achieved in certain modules (…); the highly technical, communicational and dynamic quality of the trainers.”(Trainee 10)

“(…) the diversity of trainers (…) the open environment for discussion and collective growth.”(Trainee 11)

“The fact that it is a very interactive training program, even in an “online” model, gave openness to moments of reflection and introspection that I consider very important in relation to the themes addressed.”(Trainee 25)

“The fact that several teachers and specialists in their fields were invited; and the module on intersectionality.”(Trainee 34)

“The trainers’ technical and scientific approach and their ability to stimulate the group.”(Trainee 35)

3.2.3. Facilitating Aspects of Distance Training

“The diversity of the groups of people in the training program, considering the professional background (multidisciplinarity) and the high degree of sensitivity towards LGBTI+ diversity.”(Trainer 1)

“The implementation of the online training program using the ZOOM video conferencing platform has provided a great opportunity to reach various audiences, from various geographical and educational backgrounds, reinforcing the diversity of each session.”(Trainer 3)

“The capacity of reaching diverse professionals.”(Trainer 7)

3.2.4. Barriers of Distance Training

“The difficulties and weaknesses arising from the impositions of the pandemic context, the fact that the training was not in-person, inhibiting the use of certain methodologies that would be very important.”(Trainer 1)

“Sometimes the trainees’ technological difficulties and the quality of the internet connection compromised the quality of training.”(Trainer 2)

“The unavailability of some people to be more participative (e.g., being simultaneously at work or on their way to work).”(Trainer 5)

3.3. Strategic Analysis of the “Health in Equality” Program

3.3.1. Strengths–Opportunities (SO) Strategy

3.3.2. Weaknesses–Opportunities Strategy

3.3.3. Strengths–Threats Strategy

3.3.4. Weaknesses–Threats Strategy

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Research and Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sue, D.W.; Arredondo, P.; McDavis, R.J. Multicultural Counseling Competencies and Standards: A Call to the Profession. J. Couns. Dev. 1992, 70, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.C.I. The evolution of the revolution: The successful establishment of multicultural psychology. In APA Handbook of Multicultural Psychology Vol. 1: Theory and Research; Leong, F.T.L., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, D.W.; Sue, D. Counseling the Culturally Diverse, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, M.M.; Okazaki, S.; Hong, Y.-Y. The Quest for Multicultural Competence: Challenges and Lessons Learned from Clinical and Organizational Research. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2011, 5, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, A.L.; Evans, S.A.; Risner-Butner, A.; Collins, N.M.; Mason, L.B. Multicultural Competence and Social Justice Training in Counseling Psychology and Counselor Education. Couns. Psychol. 2008, 37, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauclair, C.-M.; Hanke, K.; Fischer, R.; Fontaine, J. The Structure of Human Values at the Culture Level: A Meta-Analytical Replication of Schwartz’s Value Orientations Using the Rokeach Value Survey. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2011, 42, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.J.; Sheu, H. Conceptual and measurement issues in multicultural psychology research. In Handbook of Counseling Psychology, 4th ed.; Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.C.; Theriot, M.T. Developing Multicultural Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills: Diversity Training Makes a Difference? Multicult. Perspect. 2016, 18, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, D.W.; Bernier, J.E.; Durran, A.; Feinberg, L.; Pedersen, P.; Smith, E.J.; Vasquez-Nuttall, E. Position Paper: Cross-Cultural Counseling Competencies. Couns. Psychol. 1982, 10, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, D.W. Multidimensional Facets of Cultural Competence. Couns. Psychol. 2001, 29, 790–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J. Rethinking cultural competence. Transcult. Psychiatry 2012, 49, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, E.-H.; Park, C.-S. Effects of a Multicultural Education Program on the Cultural Competence, Empathy and Self-efficacy of Nursing Students. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2013, 43, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hook, J.N.; Davis, D.E.; Owen, J.; Worthington, E.L.; Utsey, S.O. Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sue, S. In search of cultural competence in psychotherapy and counseling. Am. Psychol. 1998, 53, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleiro, C.; Freire, J.; Pinto, N.; Roberto, S. Integrating diversity into therapy processes: The role of individual and cultural diversity competences in promoting equality of care. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2018, 18, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.B.; Constantine, M.G.; Dunn, T.W.; Dinehart, J.M.; Montoya, J.A. Multicultural Education in the Mental Health Professions: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Constantine, M.G.; Ladany, N. Self-report multicultural counseling competence scales: Their relation to social desirability attitudes and multicultural case conceptualization ability. J. Couns. Psychol. 2000, 47, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope-Davis, D.B.; Reynolds, A.L.; Dings, J.G.; Nielson, D. Examining multicultural counseling competencies of graduate students in psychology. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 1995, 26, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodowsky, G.R.; Kuo-Jackson, P.Y.; Richardson, M.F.; Corey, A.T. Correlates of self-reported multicultural competencies: Counselor multicultural social desirability, race, social inadequacy, locus of control racial ideology, and multicultural training. J. Couns. Psychol. 1998, 45, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, M.G.; Sue, D.W. Strategies for Building Multicultural Competence in Mental Health and Educational Settings; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carbado, D.W.; Crenshaw, K.W.; Mays, V.M.; Tomlinson, B. Intersectionality: Mapping the Movements of a Theory. Du Bois Rev. Soc. Sci. Res. Race 2013, 10, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCall, L. The Complexity of Intersectionality. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2005, 30, 1771–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 1989, 1989, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Brah, A.; Phoenix, A. Ain’t I a woman? Revisiting intersectionality. J. Int. Womens Stud. 2004, 5, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Moleiro, C.; Marques, S.; Pacheco, P. Cultural Diversity Competencies in Child and Youth Care Services in Portugal: Development of two measures and a brief training program. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleiro, C.; Pinto, N.; Changalal, A. Development and Evaluation of a Brief LGBT Competence Training for Psychotherapists. Transcultural 2014, 6, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, J.; Moleiro, C.; Rosmarin, D.H. Calling for Awareness and Knowledge Perspectives on Religiosity, Spirituality and Mental Health in a Religious Sample from Portugal (a Mixed-Methods Study). Open Theol. 2016, 2, 681–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candeias, P.; Alarcão, V.; Stefanovska-Petkovska, M.; Santos, O.; Virgolino, A.; Pintassilgo, S.; Pascoal, P.M.; Costa, A.S.; Machado, F.L. Reducing Sexual and Reproductive Health Inequities Between Natives and Migrants: A Delphi Consensus for Sustainable Cross-Cultural Healthcare Pathways. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 656454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers-Sirin, L. Approaches to multicultural training for professionals: A guide for choosing an appropriate program. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2008, 39, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topuz, Ş.; Sezer, N.Y.; Aker, M.N.; Gönenç, I.M.; Cengiz, H.; Korucu, A.E. A SWOT analysis of the opinions of midwifery students about distance education during the COVID-19 pandemic a qualitative study. Midwifery 2021, 103, 103161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) Analysis of China’s Prevention and Control Strategy for the COVID-19 Epidemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Govere, L.; Govere, E.M. How Effective is Cultural Competence Training of Healthcare Providers on Improving Patient Satisfaction of Minority Groups? A Systematic Review of Literature. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2016, 13, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, B.; Belton, A.; Henry, T.L.; Wrenn, G.; Holden, K.B. Improving Behavioral Health Equity through Cultural Competence Training of Health Care Providers. Ethn. Dis. 2019, 29 (Suppl. 2), 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.L. What Precipitates Change in Cultural Diversity Awareness during a Multicultural Course: The Message or the Method? J. Teach. Educ. 2004, 55, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, B.; Sheikh, A.; Timmons, S.; Stickley, T.; Repper, J. Workforce diversity, diversity training and ethnic minorities: The case of the UK National Health Service. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2020, 20, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedoyin, O.B.; Soykan, E. COVID-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbur, K.; Snyder, C.; Essary, A.C.; Reddy, S.; Will, K.K.; Saxon, M. Developing Workforce Diversity in the Health Professions: A Social Justice Perspective. Health Prof. Educ. 2020, 6, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, R.H. Exploring the use of video podcasts in education: A comprehensive review of the literature. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 820–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moridani, M. Asynchronous Video Streaming vs. Synchronous Videoconferencing for Teaching a Pharmacogenetic Pharmacotherapy Course. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2007, 71, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

|

|

|

|

| Internal environment Strategic analysis External environment | Strengths (S) | Weaknesses (W) |

| S1: Multidisciplinary and high-quality training team S2: Comprehensive modules, complementary with each other, and consistent with the perspective of intersectionality S3: Materials with diverse, valuable, and quality content S4. Practicality and relevance of the themes, both for personal and professional training S5: Increasing critical thinking awareness and a more systemic view of the person | W1: Lack of at least one face-to-face session (resulting from the pandemic context) W2: Lack of time to deepen themes and allow further discussion W3: The eLearning platform was not very intuitive to use | |

| Opportunities | Strengths–Opportunities | Weaknesses–Opportunities |

| O1: Geographical and professional diversity of trainees (different professional contexts, areas of activity, and experiences) O2: Possibility of articulation between synchronous sessions (for more experimental processes) and asynchronous (for content enrichment) O3: Development of strategies to increase health literacy on equality in the workplace and on communication with colleagues needing awareness | SO1: Create more standardized content to enable replication by trainers external to the training team SO2: Record some of the sessions to increase the replicative capacity of the training program SO3: Maximize network with partners to ensure scientific support and free training | WO1: Create moments for health professionals to meet in this network of ambassadors trained for diversity WO2. Increase practical and effective online materials (e.g., films, testimonials) to complement written materials (articles, reports) WO3: Strengthen the intersectional approach with in-depth clinical case discussion, and integrate previously obtained knowledge WO4: Improve guidance on asynchronous training |

| Threats | Strengths–Threats | Weaknesses–Threats |

| T1: Despite being an added value, the diversity of the trainees, adding the disparity in the awareness and knowledge of the themes, poses challenges to the training T2: The lack of time for health professionals reduces the number of trainees per session and limits their active participation | ST1: Increase training time with experimental methods (concrete examples) ST2: Provide innovative training, avoiding expository methodologies ST3: Establish protocols with health units to meet anticipated challenges in the implementation of change at the institutional level | WT1: Gaps between the expected and actual availability of trainees (dropouts, absences, disconnection) WT2: Difficulties in implementing best practices for online training (e.g., the image on and sound off) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alarcão, V.; Roberto, S.; França, T.; Moleiro, C. Standing Up for Culturally Competent Care in Portugal: The Experience of a “Health in Equality” Online Training Program on Individual and Cultural Diversity. Societies 2022, 12, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12030080

Alarcão V, Roberto S, França T, Moleiro C. Standing Up for Culturally Competent Care in Portugal: The Experience of a “Health in Equality” Online Training Program on Individual and Cultural Diversity. Societies. 2022; 12(3):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12030080

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlarcão, Violeta, Sandra Roberto, Thais França, and Carla Moleiro. 2022. "Standing Up for Culturally Competent Care in Portugal: The Experience of a “Health in Equality” Online Training Program on Individual and Cultural Diversity" Societies 12, no. 3: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12030080

APA StyleAlarcão, V., Roberto, S., França, T., & Moleiro, C. (2022). Standing Up for Culturally Competent Care in Portugal: The Experience of a “Health in Equality” Online Training Program on Individual and Cultural Diversity. Societies, 12(3), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12030080