3. Analytical Perspective

Transnational migrant entrepreneurs (TMEs) are understood as self-employed individuals with international migration experience who carry out economic activities involving exchanges between at least two different countries [

4,

34]. In recent years, the topic has received increased attention [

5,

35], whereby studies lie at the crossroads between economic/business-oriented research on international entrepreneurship [

36] and sociological research on ethnic economies [

37,

38]. Scholars [

39,

40] have argued that migrant entrepreneurs with international migration experience are in a particularly favourable position for mobilising resources in different countries, adapting to diverse cultural and regulatory environments, and identifying new market niches that sedentary people cannot see. In addition, scholars have studied why migrants engage in transnational business making [

41,

42,

43], their transnational networks [

44,

45,

46], the economic impacts of host and home countries [

42,

47], and the mixed embeddedness of TMEs [

48,

49]. Yet, the spatialities of TMEs have not received sufficient attention [

6]. There is still much to learn about the mobility patterns of transnational migrant entrepreneurs, and the extent to which their cross-border mobilities are useful for improving, advancing, or consolidating their businesses. Furthermore, transnational migrant entrepreneurship has rarely been studied from a perspective that combines the advances of both mobilities and migration research. Moreover, the link between spatial and social mobility is rarely explicitly addressed [

6] (p. 8).

To address these gaps, and the gaps identified in the former section, we offer an analytical framework which is grounded in the following conceptual arguments:

First, we argue that a migrant entrepreneur’s social position is a key factor in understanding how she/he is able to use her/his transnational spatial mobility for her/his social mobility. Generally, we understand social position as one’s structural position in a social field. It is “determined by a variety of factors—vertical (hierarchical, e.g., wealth) and horizontal (e.g., gender, age), objective (e.g., income, educational attainments, welfare transfers), and subjective (e.g., prestige, discrimination)” [

41]. Drawing from Bourdieu [

29], we argue that individuals who occupy elite positions have a distinct power to transform transnational spatial mobility into social mobility compared to those who occupy a peripheral position in the social hierarchical structure. Hence, social position is both a basis for achieving spatial mobility and also its outcome, for instance, when spatial mobility leads to social mobility.

Second, we contend that studying the role of geographical location is essential. Conceptually speaking, placing spatiality at the core of our research is central to understanding differences in the abilities of individuals to build socio-economic value out of spatial mobility. As human and non-human mobilities occur in concrete places endowed with physical, symbolic, and regulatory characteristics [

50,

51], we argue that the following location-specific factors need to be addressed: the materiality of the places where individuals live (size, location, connections to other places, hierarchy), the scales at which they move (home, neighbourhood, city, region, international, etc.), the presence or absence of mobility infrastructure and means of movement [

52] (telephone, computer, streets, rivers, cars, trains, boats, planes, etc.), the entities that move (bodies, goods, ideas, capital, etc.), and the existing migration channels [

53], type of mobility regimes in place [

54], and forms of support for migrants.

Third, we maintain that it is important to study the strategies that migrant entrepreneurs develop to deal with restricted or undesired spatial mobilities. By strategies we refer to actions regarding if, when, and where to move, how to move, what to do where, how to make the best of a certain location’s opportunities, and how to deal with specific spatial, socio-economic, and legal challenges [

55]. We consider formal (within legal regulation) and informal (escape legal regulation) strategies. For us, mobility strategies arise from an entrepreneur’s “mastery or command over space” [

56] (p. 115), which can involve both mobility and immobility. It includes not only the ability to move oneself across space, but also the ability to move goods, capital, ideas, and (other) people, which can reduce the need to be personally mobile. Locating these strategies in connection with an individual’s broader social and geographical position seems conceptually important to understand how they shape the different opportunities of individuals for socio-economic advancement.

4. Methodology

In this section, we introduce the methodological approach of our empirical research on transnational migrant entrepreneurs. Our working definition of entrepreneurs includes individuals pursuing self-employed economic activities (formal or informal), from medium to micro-sized businesses, with or without employees, which contribute to their livelihoods. We consider an entrepreneur to be anybody who moves goods, money, and people across physical and/or virtual spaces to gain an income, achieve a profit, and/or pursue a social objective. We are particularly interested in people with transnational businesses, which we define as economic activities involving exchanges in at least two different countries. We focus on entrepreneurs with international migration experience, i.e., people who have experienced living in a country that is different from the one(s) in which they grew up.

Our empirical material includes fully transcribed biographic interviews, geographical and mental maps, notes from ethnographic observations, and participatory

Minga workshops. We understand biographic interviews as the collection and analysis of a systematic account of a person’s life or portion of her/his life, usually by means of an in-depth, semi-structured interview [

57,

58]. We used this method because it allows a comprehensive understanding of the mobility trajectories of the studied entrepreneurs in space and over time. Geographic maps help to visualise the spatial dimension of mobility trajectories and the magnitude of the distances they travel (

Figure 1). Mental maps helped to capture the subjective perceptions of entrepreneurs regarding their wishes for the future of their businesses (

Figure 2). Finally, participatory

Minga workshops [

8] created spaces of mutual learning where participating entrepreneurs met to collectively share and discuss their mobility experiences and their efforts to get their businesses off the ground and move ahead (

Figure 3). This methodology not only allowed for a productive exchange between the entrepreneurs, but also gave them a voice, thus allowing them to be recognised as experts. We conducted biographical interviews on NGO premises, in co-working spaces, homes, shops, cafés, and after the participatory workshops. The interview process was conducted in English, German, and Spanish. We analysed the transcribed interviews using a qualitative content analysis methodology [

9], an interpretative approach that helps to identify key patterns through deductive and inductive coding procedures.

Fieldwork was conducted between 2019 and 2022, and our data collection process was iterative, with a regular back-and-forth between empirical data, theories, and analysis. The overall study sample comprises 86 transnational migrant entrepreneurs. To give due attention to the role of geographic location, we contrast the experiences of transnational migrant entrepreneurs located in different places, i.e., Barcelona (Spain), Cúcuta (Colombia), and Zurich (Switzerland). By studying entrepreneurs in three different countries, we aim to ascertain the role of geographical location in facilitating or constraining the use of spatial mobility for socio-economic advantage rather than establishing nation-based comparisons sensu stricto. The locations were chosen because of their contrasting geographical contexts, and the opportunities or constraints that derive from them, including centrality, mobility regimes, economic opportunities, support measures, and quality of infrastructure: Switzerland, a wealthy and centrally located country in Europe with restrictive migration laws; Spain, a less wealthy country in Western Europe with a liberal practice of regulating and controlling the spatial mobilities of migrants; and Colombia, an even less wealthy country with low average incomes and limited state presence in its border zones, which is located peripherally to places with better income-earning opportunities, such as Europe.

The biographical interviews were conducted by the three authors of this paper. In Colombia, Yvonne Riaño interviewed 30 entrepreneurs with migration experience who lead transnational lives between Colombia and Venezuela. She also conducted multi-sited ethnographic observations at the Venezuelan–Colombian border (Cúcuta–San Antonio). In Switzerland, Christina Mittmasser conducted 34 interviews in Zurich and carried out ethnographic observations within a local NGO supporting migrants and refugees in their journey to become entrepreneurs. In Spain, Laure Sandoz interviewed 22 entrepreneurs in Barcelona while conducting ethnographic observations in a co-working space. The socio-demographic characteristics of the interviewed individuals are presented in

Table 1 below. Before the interviews, we explained to the interviewees that all data would be used anonymously, and gained their informed consent.

Access to potential research participants was gained through various means, including online research to identify events targeting entrepreneurs (e.g., courses, workshops, social meetings), personal contacts and support organisations. The selection of case studies for the overall study sample followed a qualitative approach, whose goal is not statistical representativeness or generalising the results to the entire population, but to gain a deep understanding of the studied phenomenon. Considering all qualitative sampling as “purposeful sampling”, Patton [

7] (p. 169) highlights its scientific value: the “logic and power of purposeful sampling lies in selecting information-rich cases for study in depth. Information-rich cases are those from which one can learn a great deal about issues of central importance to the purpose of the research”. Among different purposeful sampling strategies, we chose maximum variation sampling [

59] (p. 122). This strategy is valuable because it allows for apprehending a research question from different angles, thereby achieving a greater comprehension. Additionally, it allows for generating new knowledge through the processes of comparison and contrast. Our strategy involved selecting candidates across a spectrum of dimensions, which were considered essential to empirically assessing our analytical framework, as presented above. We thus selected individuals whose geographical location ranged from peripheral to more central (Cúcuta, Barcelona, Zurich), and their social position (class, gender, education level, mobility rights) encompassed more privileged to less privileged individuals.

Despite having achieved variety, biases in the sample could not be completely avoided: for example, an overrepresentation of individuals with university education and women in the Zurich sample. Similarly, in the case of Cúcuta, most interviewees are women because they were more willing to participate in interviews than men. However, the ethnographic observations, and the Minga participatory workshops, partly compensated for these biases as several men participated in the workshops.

5. Results

How can we best summarise the wealth of knowledge provided by our empirical analysis of case studies in Barcelona, Cúcuta and Zurich? Based on the qualitative content analysis method [

9] introduced in the previous chapter, we were able to identify a typology of three situations regarding the question of whether transnational spatial mobility represents a valuable resource for the businesses of the studied migrant entrepreneurs. The three types that emerged are as follows: (I)

mobility as a potential asset but not an imperative, (II)

mobility as a key factor for business progress, and a strategy to counteract labour market exclusion; and (III)

mobility as indispensable for personal survival and a strategy to cope with an absent state and widespread armed violence.

At this point, and given the limited scope of this paper, we choose to present a brief contextualisation of our case studies followed by short biographical excerpts of interviewed individuals who represent each of the three identified types. We believe that through the prism of these biographical accounts, we can gain a deep understanding of how migrant entrepreneurs are inserted in a socio-spatial context, which includes their daily mobilities between different places for their livelihoods, their social networks, their strategies, and their embeddedness in regional, national, and international contexts. Although not represented by mere numerical numbers, these biographical accounts are theoretically valuable to illustrate different abilities and conditions of spatial mobility, thus bringing to light the role of social position, geographical location, and strategies in shaping the options of transnational migrant entrepreneurs.

The first type applies specifically to interviewees who can use transnational spatial mobility as an asset for their business while also having a high degree of freedom for choosing how, when, and where to move. It was found mainly in the case study in Barcelona, although not all interviewees located in Barcelona belong to this type, and several interviewees from the case study in Zurich could also be clustered here. All the migrant entrepreneurs we associate with this type have European nationality or the nationality of a rich non-European country, such as the United States or New Zealand. They enjoy a privileged social position in the sense that they have a high level of education (university degree or equivalent), capital that mitigates the risks of starting a business, a stable legal status in the country where they reside, a nationality that enables them to travel internationally, a supportive social network, and few family obligations. Moreover, they are familiar with information and communication technologies, which enables them to sell services virtually to distant places, for example as consultants, software developers, translators, and designers. Some of them are young entrepreneurs at the beginning of their career who strategically decided to move to a location that would be beneficial for their business. One interviewee in Barcelona, a Danish woman selling consultancy for IT development projects, explains:

“There’s more of an international environment [in Barcelona], which also makes it easier to get the right contacts because people are from all over the world. So, I think that’s why I’m still in Barcelona. Because, if we were only talking about money, it would of course be a lot cheaper to move somewhere else in Spain. But I do like the environment here. I’m also going to some business lunches, and I am part of a lot of networks and everything.”

Other interviewees are older people who decided to capitalise on their life-long working experience and network to start a transnational business. In this case, too, their decision to migrate was carefully considered, as illustrated by this US American computer scientist who settled in Barcelona after travelling in Asia with his wife for three years:

“I was just googling all the time, just searching for different residency options. […] We have a bunch of factors that we consider, about safety and economy, internet speed, weather, healthcare, infectious disease prevalence, and ease of immigration. […] We chose Spain because it has a really attractive residency programme that met a lot of our needs. And then we chose Barcelona because Barcelona, among cities in Spain, has the best start-up scene, so has a lot of young people, a lot of technology and so has a really vibrant start-up scene.”

This type is a good illustration of the class of privileged people to which Beck [

1] and Weiss [

3] refer when they argue that the ability to move and to choose locations where one’s skills and assets are most valued has become a crucial factor in social differentiation in our world. This does not mean, of course, that they do not encounter difficulties. Several of the interviewees, in particular the younger ones, struggled to make their business profitable and experienced a lot of stress being their own boss and dealing with the pressure of finding clients and being successful. Nevertheless, their social position, associated with the ability to strategically choose a geographical location that enables them to fulfil their aspirations and connect with the rest of the world through digital technologies and occasional travel, are clear assets that expand their options as entrepreneurs. Moreover, for these interviewees, both the decision to spatially move and the decision to start a business were embedded within a broader lifestyle project associated with a quest for personal freedom and development. For this reason, several interviewees chose at some point to settle and move less, which they could afford to do without harming their transnational business, thanks to their location in a dynamic international environment and because most of their activities were performed online.

To illustrate the first type in more detail, we present the biography of Harry Davis:

Harry Davis (All names have been anonymised) is a 25-year-old British and Danish national who grew up in the UK.

As he describes himself, he is from a “lucky background”: his father managed to rise significantly on the social ladder and became the CEO of a large multinational company. Harry founded his first online media company from home when he was 16, building on his computer skills and the business experience of his father. He studied economics in privately run institutions and accumulated various employment and living-abroad experiences, working in banks, start-ups, and a Russian gas company in the UK and China. He then completed an MBA in Barcelona, which he coupled with jobs in Argentina and Peru, as well as a student exchange in the US. He had the idea for his current company during an “entrepreneurship

trek” he organised in Berlin. There, he also met his co-founder, an architect and experienced businessperson with access to capital from his family business in the Middle East. The concept of Harry’s company consists of identifying promising start-up ideas and investing the necessary money to launch them. At the time of the interview, he was in the hiring process for his first project, which consisted of replicating, in Spain, the business model of a company in the education sector based in India. In parallel, he works as a consultant in finance to secure a stable income. The money invested in the company originates mainly from his co-founder’s network. Harry, however, is also planning to apply for EU and UK government grants. He currently lives in Barcelona, while his company is officially registered in the UK. His decision to settle in Barcelona was based on lifestyle reasons, as he enjoys the city’s culture and climate, and the ability to live not too far from the UK. Yet, he deplores the slowness and complexity of Spanish business regulatory processes and finds the UK more attractive for business in terms of administration and taxation treaties. Except for two to three trips a year to the UK to deal with administrative issues, Harry does not currently need to travel internationally for work, as most of his activities take place online. He is supported by a network of California-based investors who offer seed funding and online training. Nevertheless, Harry is mobile within Barcelona, using networking events to identify potential candidates to hire for his current project. As part of his daily routine, he uses the co-working space and networking opportunities offered by a luxurious private club for “creative souls” in the city centre, of which his co-founder is a member. He also receives legal advice from a state-funded programme for entrepreneurs in Barcelona. His co-founder, in contrast, divides his time between Kuwait, Spain, and other locations. Harry plans to travel more soon, as the project’s technical development will be continued outside of Spain, probably in Ukraine, and he wants to be physically present and in contact with the team on a regular basis to supervise their work. Although his start-up is not generating any money yet, Harry is confident about the future and does not hesitate to make ambitious plans. He is eager to prove his value as an entrepreneur, but he also acknowledges: “I’m from a background where I’ve got financial means behind me [...] It’s ok if I screw up.”

This story illustrates how social position, geographical location, and strategies interact with each other in a virtuous circle that, in this case, reinforces Harry’s position as a socially valued, globally oriented entrepreneur. He is aware that his family situation, and his association with a partner who has capital and is physically mobile, give him the economic security and confidence to invest in risky projects. His two European nationalities and mastery of the English language are advantageous to travelling and developing a socially valued cosmopolitan orientation. His work experiences and studies in various countries brought him important knowledge about how to run a company, access investors, and manage a team. Based in Barcelona, he can easily connect with the rest of the world, either digitally or physically, due to a wealth of mobility infrastructures (e.g., airports, trains, buses, roads). His global orientation enables him to use the various facilities available for entrepreneurs in the city (e.g., co-working spaces, fairs and events, state-funded support) while avoiding location-specific constraints (e.g., bureaucratic slowness, unattractive regulations). Interestingly, Harry builds on a combination of past mobility experiences and moorings in international networks and institutions, which he can use to develop his business without physically travelling at present. With no strong attachment to a specific place, a high capacity to physically move, and the ability to develop international networks through technologies, he enjoys the freedom to choose whether or not to move and to decide where he wants to settle and further expand his transnational business activities. Spatial mobility emerges as an asset for his entrepreneurship to the extent that it interacts with his social position and experiences, making it possible for him to choose from a broad array of high-end, socially valued symbolic and material resources on a global scale. Although he currently does not make full use of his ability to physically move because he can attract ideas, capital, and people, he can choose to change this in the future. Hence, he enjoys a high degree of control over his mobility and that of other human and non-human entities, which he actively uses to develop his transnational business.

The second type was mainly derived from the case study in Zurich, although not all interviewees located in Zurich belong to this type (as explained above, some belong to type 1, i.e., those with a European nationality, a tertiary education in technology or business-related fields, and a somewhat stable financial situation). Type II specifically refers to those interviewees who use cross-border business creation to counteract labour market exclusion. Most of them are non-Europeans and/or women who moved to Switzerland to accompany their partners (or, in some cases, to request asylum). As reunited family members or refugees, they all enjoyed a stable legal status and, to some extent, mobility rights at the time of the interview. Although the majority did not face difficulties settling in Switzerland, they struggled to enter regular employment commensurate with their university qualifications. Statistics suggest that the Swiss labour market is favourable to highly skilled migrants compared to other countries [

60] (p. 116). However, research has shown that women and non-Europeans particularly struggle to make full use of their skills [

61]. They often experience a devaluing of their former work experiences due to discriminatory representations among employers [

62], inadequate integration programmes that tend to channel participants into precarious labour sectors [

63], a lack of professional networks, limited knowledge of the Swiss labour market, and a lack of fluency in the local language [

61] (p. 8). Many interviewees in Zurich, because they were in situations of skills mismatch or unemployment, decided to engage in an entrepreneurial career, capitalising on their migration-specific resources. Moving goods, services, ideas, and/or capital allowed them to restart their professional lives and become actors in the Swiss economy. As one Syrian interviewee, who joined his partner in Zurich and now sells Syrian crafts and furniture in Switzerland, stated:

“When you get one rejection after another it really demoralizes people. You really tend to believe that I’m not good enough to do anything, to be accepted. So, it’s a very critical, very bad position. [...] In terms of self-esteem, it’s definitely building up at the moment when people approach you, saying: Well, you have a really interesting project. I would love to support you or be part of it.”

Spatial mobility thus emerges as an important asset for this type of interviewee. By travelling, they maintain professional contacts outside of Switzerland, accumulate knowledge, and/or acquire resources for production and selling. Being based in Zurich, a city characterised by its central location in Europe, safety, high density, and good quality of transportation infrastructure, they enjoy a high degree of connectedness to locations around the globe. Yet, because of their social position as “marginalised elites” [

61] (p. 10), these interviewees also face difficulties establishing an entrepreneurial career, and thus struggle when crossing borders for business purposes. As they could not accumulate savings through previous employment, many experience financial limitations and often rely on their partner, social welfare, or side jobs to afford their cross-border mobilities. Interviewees with children, especially women, said they cannot take the time to travel on a regular basis due to care responsibilities. This is linked to gender inequalities within the professional sphere in Switzerland and a lack of inexpensive childcare options [

61] (p. 2). Difficulties in moving can also be explained by features of the localities they engage with in their business projects, including a lack of relevant infrastructure and political instability, as in the case of refugees who cannot travel to their country of origin. Yet, interviewees of this type can use various strategies to circumvent the above-mentioned difficulties and stay in control of their mobilities and immobilities. They engage with digital communication tools and outsource business tasks to family, friends, and former work colleagues abroad. It enables them to navigate their transnational business activities without the need to be physically present. These interviewees also highlight the important role of support measures in Zurich, such as non-governmental organisations, which provide support to migrant entrepreneurs. By participating in training programmes, they can access local networks and acquire knowledge about resources in that place, which decreases their need to move spatially.

To illustrate this type, we present the biography of Valeria García:

Valeria García is a 33-year-old Colombian who grew up in Bogotá with her single mother. After she finished high

school in Colombia, she moved to New Zealand with the financial aid of her aunt, where she learned English and worked as a nanny for four years. There,

she met her future Swiss husband. After a short return to Colombia, she moved again to Barcelona and then to Milan, where she studied fashion design. After

obtaining a bachelor’s degree in 2013, Valeria got married and moved to Zurich to live with her husband. Failing to find a job in the fashion sector in Switzerland, she started working as a nanny again. Yet, she wanted to create a wedding dress label. In the interview, she explains that creating a business in Switzerland has so far been impossible due to a lack of social contacts, language skills, economic capital, and knowledge of the Swiss market. She tried to enter the Swiss market twice without success. In Colombia, her situation is different. She decided to use her spatial knowledge and contacts there to develop her entrepreneurial project. Now, she owns a shop in the centre of Bogotá, which is run by her mother and cousins. She has access to wealthy clients and a tailors’ workshop in the city outskirts, where cheap labour is available. While the wedding dresses are designed in Zurich, they are finalised and sold in Colombia. Thereby, Valeria moves goods (dresses, fabrics, etc.), ideas (designs, business models, etc.), capital (salaries, remittances, investments, etc.), and bodies (family members) across borders. She travels regularly for business, not only to Colombia but also to France and China to import new fabrics, and to Brazil and Peru to explore new markets. She highlights, “This opportunity to travel to all these places really helped me.” However, travelling between these places is costly and takes time. She needs to coordinate many of her business activities digitally, using tools such as Skype, email, social media, and her website; furthermore, due to the time differences, she often works during the night. Valeria also

sometimes brings her mother and cousins to Switzerland to help her prepare collections for fashion shows or to take care of her son so she can travel

abroad more easily. In practice, many of her activities are rather informal. For instance, her shop in Colombia is officially registered in her mother’s name because of Valeria’s official residence in Switzerland. Apart from her mother and cousins in Colombia, she also receives support from her husband. Not only did her bi-national marriage with a Swiss citizen provide her with cross-border mobility and settlement rights—which, due to her Colombian nationality, she did not have in the past to such an extent—she also relies on him financially for daily living expenses, as she invested all the money she earned working as a nanny in Switzerland in her business in Colombia. Yet, Valeria concludes that her business is growing. She is portrayed in different fashion magazines in Colombia and can support her family in Colombia as well as pay her employees. She joined an NGO-based entrepreneurship programme for migrants and refugees in Zurich, which supports her with expertise, encouragement, and a local network to attract Swiss clients.

In this story, we observe that Valeria uses spatial mobility to develop a transnational business in Colombia and to counteract her exclusion from the labour market in Switzerland. She not only moves between her country of origin and country of residence but also expands her business activities to other countries. Therefore, she is circumventing difficulties in one country by using resources in others, and thus strategically capitalises on the different social positions she holds in different geographical locations. In Colombia, she was identified as a highly skilled emigrant creating employment for others, and could therefore start her business quickly. In Switzerland, she could not initially use her educational skills within the labour market but used her migratory status to access support structures. Additionally, she leverages different standards of living between two countries by investing the higher-value currency she earns from a low-skilled job in Switzerland to pay several employees in Colombia. For Valeria, immobility is not an option since travelling is indispensable to her business. Care obligations and financial limitations create constraints in this regard, but she stays in control of her mobilities and immobilities due to the support of her transnational family and digital communication strategies. Under the described circumstances, spatial mobility thus becomes a form of capital that can be converted into social mobility and socio-economic advancement.

The third type applies to interviewees for whom transnational spatial mobility is essential to survival, and is a strategy to cope with an absent state and armed conflict. This is borne out in the case study in Cúcuta (Colombia) and its surroundings. The migration and mobility trajectories of the interviewees are characterised by violence and an absence of human rights. Most of them have basic education and grew up in rural areas of Norte Santander, an area in Colombia’s north-east, bordering Venezuela. Given the lack of presence of the Colombian state in the area, the guerrilla and paramilitary groups have disputed control of the territory for decades. Fighting among these two groups has forced many inhabitants of Norte Santander to leave their homes and seek out new livelihoods elsewhere. In the early 2000s, research participants emigrated to Venezuela, escaping violence in Colombia and attracted by the earning opportunities generated by soaring oil prices in Venezuela [

64]. At first, many were able to set up their own business and experience a high standard of living. However, in 2015, following the alleged attack of Colombian paramilitaries on members of Venezuela’s national guard, many Colombian migrants living in cities by the border between Colombia and Venezuela began to be persecuted by the Venezuelan government [

65]. Many of them were deported overnight, losing many of their material resources and equipment for their small businesses. A woman recounts her experience:

“As we were Colombians, they accused us of being paramilitaries. The houses of some Colombians were marked with the letter “T”, which meant that they had to be demolished. Others were marked with the letter “D”, which meant that they were in good condition and did not have to be demolished... It was terrible, because we were crying over our houses, the collapsed houses. We took what goods we could to Cúcuta at night across the Táchira river.”

Today, most research participants live transnational lives between the cities of Cúcuta (Colombia) and San Antonio del Táchira (Venezuela) and struggle to survive. Cúcuta is peripherally located in Colombia (404 km from the country’s capital Bogotá) on the border of Venezuela. Both cities are geographically close as they are connected by the 300-metre-long Simón Bolívar Bridge across the Táchira River. In order to survive, research participants conduct transnational business between both cities, which includes the transport and sale of foodstuffs, medicines, petrol, and alcohol, as well as the provision of social, cleaning, and personal care services. Since Venezuela’s president has kept the official border between Colombia and Venezuela closed since 2015, most cross-border entrepreneurs must move through an informal pass, known locally as la trocha, which connects the two countries through the bush and the Táchira River.

Owing to the lack of job opportunities in Cúcuta, and an absent Colombian state, cross-border spatial mobility across the

trocha represents an important asset for the type-III interviewees. The

trocha is indeed a key source of income for many small entrepreneurs in Cúcuta. There is a great demand for transporting goods between Colombia and Venezuela, which cannot be carried out across the official border either because it has been closed for a long time or because the corrupt guards charge too high a fee for small entrepreneurs to bring their products to sell in Venezuela. However, movements across the

trocha can be dangerous as the territory is controlled by illegal armed groups, who threaten and extort money from the crossers (lower fees than the guards, however), and impose their own form of criminal governance [

66].

A 25-year-old woman who transports medicines and foodstuffs daily across the trocha expresses the dangerous situation in which she lives:

“I think there is a part of my brain that tells me that one day I could die on the trocha”…“That’s why I’m studying. Because I want to give everything to my children and I know I’m going to achieve it. So, I am studying to learn more things, to prepare myself and to have a better job and to help my children get ahead.”

To illustrate the third type in detail, we now introduce Enrique Villarín’s biography:

Enrique Villarín is a 38-year-old Colombian who grew up in a rural area controlled by guerrillas. His family was forcibly displaced in 1992 by armed right-wing paramilitaries, and moved home three times in consecutive years. Around 1995, they began to work on a farm near the border of Venezuela. When a paramilitary group perpetrated a massacre there, Enrique and his family managed to escape to Cúcuta. There, Enrique and his

siblings learnt to sew jeans and t-shirts and commuted daily to San Antonio de Táchira (Venezuela) to work at their cousin’s factory. In 2007, they migrated to San Antonio where they set up a business manufacturing jeans and t-shirts and sold them in Colombia and Venezuela. They obtained a house in “Mi Pequeña Barinas”, a squatter settlement in San Antonio on the Venezuelan side of the border. Despite not having a residency visa in Venezuela, Enrique could easily cross the border by bribing the border guards. In 2015, however, the situation changed dramatically after the new president, Nicolás Maduro, ordered the closure of the border. Colombians’ houses were raided and families evicted to Colombia. Enrique and his family escaped to Cúcuta for approximately six months, until the situation calmed down, and then returned to Venezuela. Groceries, work, and educational opportunities were lacking, but they benefited from free housing, cheap electricity, water, natural gas, and petrol, and could illegally cross the border daily to access resources in Colombia. On the other hand, due to hyperinflation, which began in Venezuela in 2017, the value of the bolivar, the official currency, fell drastically, and Enrique and his family lost their savings. In 2022, despite still owning the sewing machines, the knowledge, the labour force, and the necessary space to manufacture clothes, Enrique and his family were still not able to restart their business in San Antonio because they lacked the capital to purchase raw materials (USD 5,500). Enrique’s request for credit in Colombia was denied due to a lack of collateral. Furthermore,

Maduro’s government kept the official border between Colombia and Venezuela closed. In the absence of any foreseeable support measures from the Colombian government, and a closed border, Enrique decided to put his clothing business on hold, although, as he states: “My dream is to have a clothing factory to be able to support my family and also help those most in need and provide my knowledge to those who need it, so that they can get ahead and not depend on anyone.” As a temporary strategy, Enrique decided to use his body, his transnational circulatory experience, and his professional and kinship networks to enter the risky occupation of “maletero”. A maletero is a freelance porter who illegally carries goods on his back across the informal border. A maletero’s work is highly risky, as illegal armed groups control movements across the border, threatening and extorting money from informal crossers. Enrique is paid per trip depending on weight, which can be up to 120 kilos. His economic activities are thus part of a complex transnational informal economy taking place at the Colombia–Venezuela border.

Overall, Enrique´s life is characterised by multiple forced mobilities within Colombia and Venezuela, mostly resulting from armed violence, an absent Colombian state, and a politically unstable Venezuelan state. His ability to move between these countries is a potential asset for his textile business—and key to his maletero activities—but does not lead to social mobility, merely to survival. Personal mobility is a commodity that Enrique sells to survive because tradespeople are willing to pay for it. In this context, however, the value of mobility is associated with the risks involved. His social position is characterised by a constant struggle for a better life, which he cannot realise given the violent and volatile political and socio-economic contexts and the fact that he has no stable income, no capital in Colombia, no state support, little formal education, and no residence visa in Venezuela where he sleeps. His geographical location plays a double role here: on the one hand, it is a great disadvantage because doing business in a violent region of Colombia and a politically unstable area of Venezuela—where the government has imposed immobility—results in a constant struggle for survival. On the other hand, it allows Enrique to mobilise advantages in different cross-border locations to conduct his maletero business. In terms of strategies, Enrique uses his spatial knowledge of where to cross, when to cross, how to cross, and who to contact to move goods between countries, thus compensating for the total social exclusion and immobility imposed by Venezuela’s government and lack of support from the Colombian government. In sum, Enrique Villarín’s case illustrates how a precarious social position, a violent and unstable context, and the strategy of using spatial knowledge and transnational contacts to take advantage of the trocha for entrepreneurial activities create opportunities for conducting transnational business. This allows him to survive, albeit under risky and uncertain conditions.

6. Discussion

What do the above biographical accounts tell us regarding our research interest? We raised the question of to what extent, and under what conditions, the ability of transnational migrant entrepreneurs to move across national borders becomes an asset for their business, and why. Our empirical results reveal unequal opportunities. Harry Davis illustrates the first type, using spatial mobility as a potential resource to develop his entrepreneurship project; however, it is not an imperative since he makes use of digital technologies, an international and centrally located geographical position, and a wealthy and transnationally mobile business partner. Valeria García demonstrates the second type, where transnational spatial mobility is key to realising professional aspirations and a strategy to counteract exclusion from the labour market in Switzerland. The third type is exemplified by Enrique Villarín, for whom transnational spatial mobility is indispensable to survival and a strategy to cope with the absence of the state and widespread armed violence. His spatial mobility, however, does not lead to social mobility, but merely to survival.

Our empirical results seem to confirm our conceptual proposition that the ability to use spatial mobility as an asset for business creation depends on the interplay between a migrant entrepreneur’s social position, geographical location, and strategies.

Overall, we observe a

continuum of situations among the studied 86 migrant entrepreneurs where advantages and disadvantages cumulate or work to their benefit or their detriment. Type-I migrant entrepreneurs are lifestyle migrants [

67] who can choose where to live. They are in an advantageous social position to start their businesses owing to their economic capital, high education level, spatial mobility rights, state support, and supportive network. In contrast, migrants belonging to the type-III category are individuals with repeated forced mobilities who had no choice but to migrate and find themselves in precarious socio-economic situations. They have no start-up capital (their migration savings disappeared with hyperinflation), a limited education, limited spatial mobility rights, traumatic experiences of forced migration, no state support, and relatives with very few resources. In contrast, migrant entrepreneurs belonging to the type-II category are mid-way along the continuum. As family migrants, they are able to gain international mobility rights, but they face discrimination in the labour market as non-EU citizens from poorer countries.

Opportunities and constraints are also shaped in great part by differentiated geographical location: migrants in typologies I and II, whether they are EU- or non-EU nationals, enjoy the locational advantages of living in Europe, in countries with relatively stable economies and political systems, centrally located and dense urban areas with good infrastructure, good communication systems, and access to migrant support schemes. By contrast, type-III migrants live in peripheral locations (such as the Colombia–Venezuela border) where they receive no state support, face precarious infrastructure, and extremely violent and unstable economic and geopolitical contexts.

Furthermore, although all three groups of migrants use creative strategies to overcome the challenges they face, migrants belonging to group III must not only multiply their efforts, as they face many more challenges, but must also move across borders in dangerous conditions. There exist strong inequalities among the studied entrepreneurs regarding ease and safety of movement. The least effort is required by migrants in the type-I group (e.g., Harry Davis), as they enjoy important mobility rights and can hire others to move ideas and capital on their behalf, or use digital technologies to conduct transnational business. More effort is required of migrants in the type-II group (e.g., Valeria García) who cannot always afford to delegate tasks but must move goods and people across national borders themselves. A great effort is required of migrants in the type-III group (e.g., Enrique Villarín), who must personally undertake risky cross-border journeys by foot, endangering their body and the goods they transport.

Finally, women in all three typologies face greater disadvantages than men. Their gender constrains their cross-border spatial mobilities as they carry the main responsibility for reconciling paid and unpaid work within their households (see Valeria García’s example in type II). Moreover, in typology III, women have not only suffered internal displacement and deportation like men, but also sexual violence through gang rape and domestic violence. They must run their businesses while carrying the added trauma of forced displacement and rape. This reflects what has been shown before regarding the labour market integration of migrants: gender is a main factor shaping unequal opportunities for women independently of their education and citizenship [

60].

Our results bring nuance to the hypothesis advanced in the motility [

10] and mobility capital literature [

11] that being able to move across physical space is a resource for socio-economic advancement. We argue that spatial mobility can only be considered a form of capital if transnational migrant entrepreneurs are in control of their mobilities, if such mobilities match their personal aspirations, and if they can be performed under conditions of safety and security. This conclusion is particularly well-illustrated by type III, where migrant entrepreneurs are highly mobile across borders, but such mobilities stem from a lack of economic opportunities. Entrepreneurs do not fulfil their personal aspirations, and mobilities put their lives at risk. Hence, we see the link between spatial mobility and socio-economic advancement not merely as direct causality but as a spiral of reinforcing interactions shaped by inequalities and power relations occurring through space and time.

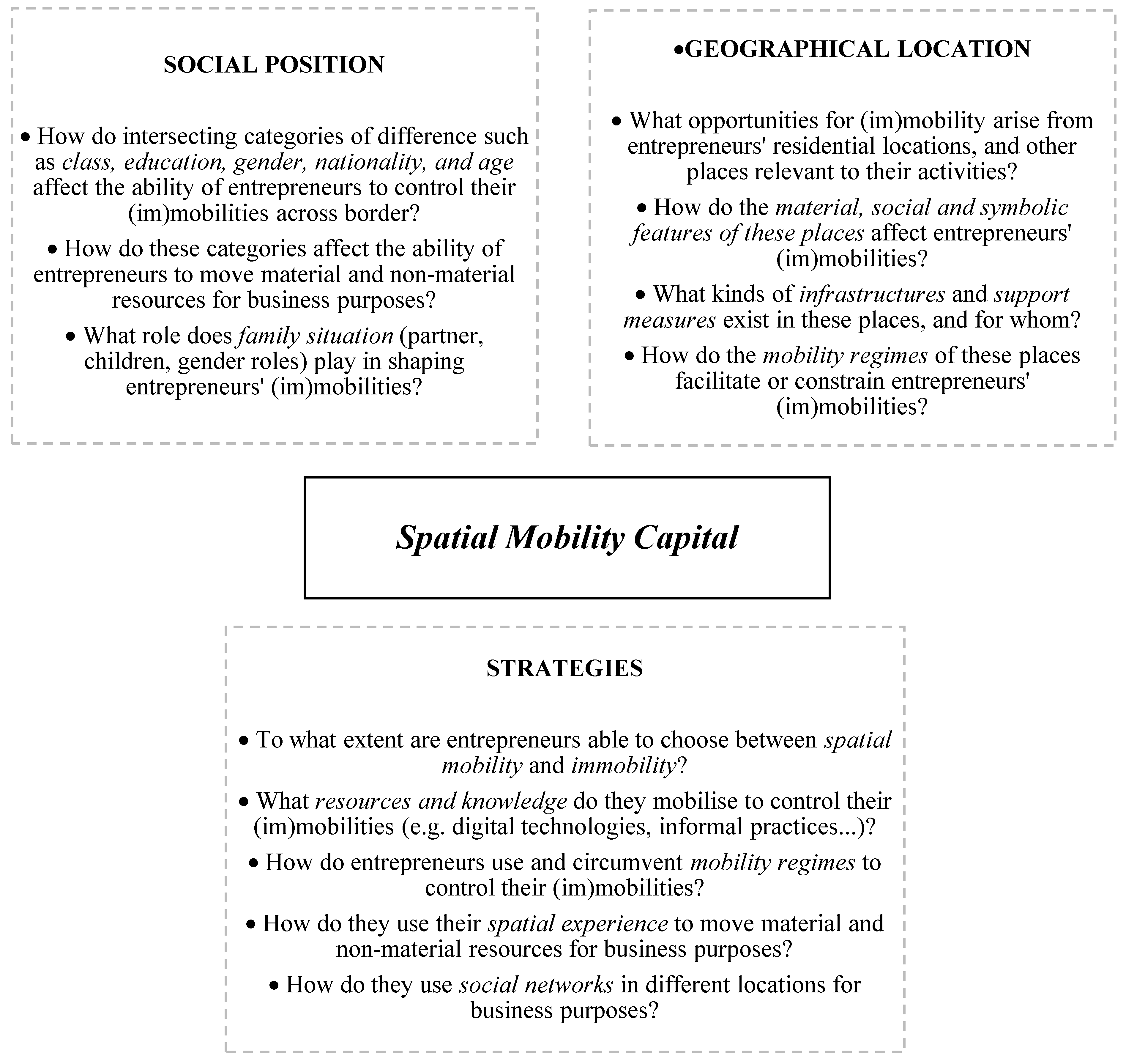

Based on these reflections, we have formulated the concept of spatial mobility capital. We define it as the ability of individuals to control desired and undesired mobilities across national borders, according to their own socio-economic needs and personal aspirations, and under conditions of safety and security. We envision it as an unequally distributed resource that emerges from the interplay between an individual’s social position, geographical location, and strategies. We argue that this concept can further our understanding of spatial mobility as an asset at the transnational scale. We propose below (

Figure 4) a set of questions for each one of the three proposed analytical dimensions, which can be useful for future empirical research.

7. Conclusions

This paper investigated to what extent, and under what conditions, the ability of transnational migrant entrepreneurs to move across national borders becomes an asset for their businesses. After a critical overview of existing contributions, we empirically examined this question by using ethnographic observations, biographical interviews, geographical and mental maps, and participatory Minga workshops. We contrasted the experiences of 86 transnational migrant entrepreneurs located in different places, including Barcelona (Spain), Cúcuta (Colombia), and Zurich (Switzerland). Our exploratory study offers three main contributions to theory building.

First, our results indicate that our initially proposed analytical perspective has empirical foundations. Indeed, the differentiated possibilities of migrant entrepreneurs to convert their ability to move across national borders into advantages for their businesses depend to a large extent on the intersection of their social position, location in geographical space, and strategies. We identified a

continuum of situations among the studied migrant entrepreneurs where advantages and disadvantages in terms of social position, geographical location, and strategies intersect to their benefit or their detriment. Although the strategy of spatial mobility is potentially valuable for the less advantaged and the more advantaged migrant entrepreneurs, the need to move across borders themselves is an imperative for the less privileged, while the more privileged can delegate spatial mobility to others. Further, we observed different geographies of risk and uncertainty depending on the geographical location in which the entrepreneurs were based. Migrants living in Europe move transnationally across relatively safe and supportive spaces, whereas migrants in Colombia are subject to moving in a “grey space” [

68], which is threatened by continuous “unmapping” [

69] by armed groups and government forces. The consequences are that migrant entrepreneurs in Europe can aspire to social mobility, whereas those in Colombia experience hazards and the continuous adjustment of their mobility strategies for survival in their social space. Their transnational mobilities are a desperate attempt to exercise agency, but sadly from a position of extreme insecurity [

25].

Second, we revealed significant inequalities among the studied entrepreneurs regarding their ability to use transnational spatial mobility for business improvement. To understand the nature of these inequalities, we uncovered a typology of three types of situations: (I) spatial mobility as a potential asset but not an imperative; (II) spatial mobility as a key asset for business progress, and a strategy to counteract labour market exclusion; and (III) spatial mobility as indispensable for personal survival and a strategy to cope with an absent state and widespread armed violence.

Third, to advance the former arguments, and to complement other studies on the relationship between spatial mobility and social mobility [

10,

11], we proposed the concept of

spatial mobility capital, a core concept of our approach. We defined it as the ability of individuals to control desired and undesired mobilities across national borders, according to their own socio-economic needs and personal aspirations, and under conditions of safety and security. For spatial mobility capital to be beneficial, three key conditions must be met: transnational migrant entrepreneurs must be in control of their mobilities; such mobilities need to match their personal aspirations; and they need to occur under conditions of safety and security. In order to facilitate the empirical use of our proposed approach, three key dimensions are thus highlighted by spatial mobility capital: control, aspirations, and safety.

One of the limitations of this research is that it studied the situation of entrepreneurs at one specific time. Clearly, the circumstances of their transnational businesses are not static but will evolve in the future. Therefore, it is important to carry out more longitudinal studies to understand how the trajectories of entrepreneurs and their businesses evolve over space and time. Furthermore, the question of the role of spatial mobility capital for the businesses of migrant entrepreneurs deserves further attention as it is a promising topic. We hope that our results will contribute to raising awareness among researchers that although many migrants can move across borders, this does not mean that their opportunities for social mobility are the same. There are large differences among individuals and social groups, as this study has revealed, and our task as academics is to uncover possible new forms of inequality by carrying out more empirical comparative studies among further research subjects, and under varying conditions, in different geographical contexts around the world. Additionally, we recommend using different complementary qualitative methods, such as ethnographic observations, biographical interviews, geographical and mental maps, and participatory workshops, as each of the methods reveals a different facet of the phenomenon studied.

Finally, our study has shown that the task of contrasting different locations is complex, so it is important to develop a solid conceptual and methodological basis before starting fieldwork. Therefore, to facilitate the empirical task of researchers working on the relationship between spatial mobility and social mobility, we recommend that they start with a rigorous analytical model, such as the one proposed here, and then enrich it with the specific results of the contexts in which they work. Thereby, we hope to contribute to formulating sound theories to explain social inequalities in the use of transnational spatial mobility as a resource for social mobility. Finally, we need to encourage policy makers to develop differentiated policies, which take into account the diversity of social positions (gender!), geographical locations, and the possibilities for action among different types of migrants.