Finding a Suitable Object for Intervention: On Community-Based Violence Prevention in Sweden

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Collaborative and Systematic Crime Prevention

3. Previous Research

4. The Study: Data Collection and Analysis

5. Projected Knowledge

6. Results

6.1. Preventionist Creaming

The foundation Safer Sweden was asked to perform a safety analysis in [case A] last autumn. And they produced a plan of action with concrete measures and later long-term goals. … And it is … It places the emphasis on the physical environment. That is, how to make changes in the physical environment to increase security and that stuff. But we try to … Now we talk to, well the housing companies in A, on getting a joint project to ensure that we have guaranteed … Yes, for example to pick up litter and manage walkways … You see, there are many things of that nature they pick up in analysis.(Security coordinator in A)

6.2. Pulling Intertwined Strings

Incident of a ten-year old student intending to strangle a classmate at school. Discussion about whether there is a more far-reaching threat scenario to consider. The father of the family to which the ten-year old belongs has applied to the social services for protection of the family, as he suspects that one of his older sons plans to execute a man in a rival family to revenge a shooting that took place one year before this incident. If the murder is committed, the father expects retaliation. In retaliation for the earlier shooting, another of the father’s sons has already been exposed to a revenge attack in which he was severely injured by gunfire and is now permanently wheelchair bound. This son has been placed in a protected residence because further threats against his life have been articulated by rival parties (the family is threatened by a dominant network in another PVA). The group discussed whether yet another criminal network from the other side of town might be involved in the conflict. According to the father, his son ‘must’ kill a member of the rival family network.

6.3. Prevention as a Double-Edged Sword

Let’s say for instance this weekend when we had a… Well, we had a shooting this weekend and we found cartridges, cartridge cases. Communicating that part makes people scared of A. But the incident in itself is between two groups and has nothing to do with a third party. And it is very important that we communicate that this does not mean a risk for third parties, because it is between two groups, to sort of … still create peace in the area. And it is delicate communication because this is not something we can … We cannot communicate this on our website or the like, but it is word of mouth communication.(Head of security in A)

In one of the schools in the neighbourhood, a boy masturbated in front of a female teacher and molested her sexually by touching her body. The principal announced that she wanted to report the incident to the police. However, another teacher at the school shared information about the boy’s family with the prevention group. According to this teacher, there was a high risk of a severe battery of the boy should the parents find out what had happened. As a result of this information, no report of concern about the boy was made to the social services.

7. Discussion

We’ve got a problem and we solve it through a collaborative meeting. And we meet, check, and it [the problem] is solved. But is it?(Security coordinator specialized at religious extremism in B)

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | The project received funding from the research council FORTE, Ethical approval was requested, and an advisory statement obtained, Dnr: 2019-01858. Since the project does not involve sensitive personal data, it falls outside the legislation on research ethics. |

References

- McCave, E.L.; Rishel, C.W. Prevention as an explicit part of the social work profession: A systematic investigation. Adv. Soc. Work 2011, 12, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnecki, J. Stöta på Patrull—En ESO-Rapport om Polisens Problemorienterade Arbete. [Tackling Obstacles: An ESO Report on the Police’s Problem-Oriented Work]; Regeringskansliet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- SOU. Kommuner mot Brott. [Municipalities against CRIME]; Elanders: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, J. The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention. A short presentation. J. Scand. Stud. Criminol. Crime Prev. 2005, 6, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvall Malm, D. Det Socio-Polisiära Handlingsnätet: Om Kopplingar Mellan Polis och Socialtjänst Kring Ungdomars Kriminalitet och Missbruk. [The Socio-Police Action Net: On Connections between the Police and the Social Services in Cases of Youth Criminality and Drug Abuse]; Umeå Universitet, Institutionen för Socialt Arbete: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Forkby, T. Organisational Exceptions as Vehicles for Change: Collaborative strategies, trust, and counter strategies in local crime prevention partnerships in Sweden. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2020, 23, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, P.-O. Effektiv Samordning av Brottsförebyggande och Trygghetsskapande Arbete i Socialt Utsatta Områden. [Effective Collaboration around Crime Prevention and Safety Promotion Efforts in Socially Disadvantaged Neighbourhoods]; Urbana Studier, The University of Malmö: Malmö, Sweden, 2018; Available online: https://www.divaportal.org/smash/get/diva2:1410304/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Johansson, K. Crime prevention cooperation in Sweden: A regional case study. J. Scand. Stud. Criminol. Crime Prev. 2014, 14, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillimore, J.; Humphries, R.; Klaas, F.; Knecht, M. Bricolage: Potential as a conceptual tool for understanding access to welfare in superdiverse neighbourhoods. In IRIS Working Paper Series; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnecki, J.; Carlsson, C. Introduktion till Kriminologi. 2, Straff och Prevention. [Introduction to Criminology. 2. Punishment and Prevention]; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Takala, H. Nordic cooperation in criminal policy and crime prevention. J. Scand. Stud. Criminol. Crime Prev. 2004, 5, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A. Crime Prevention and Community Safety: Politics, Policies and Practices; Longman: Harlow, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gilling, D. Community safety and social policy. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 2001, 9, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G.; Gilling, D. ‘Mission impossible’? The habitus of the community safety manager and the new expertise in the local partnership governance of crime and safety. Crim. Justice 2004, 4, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A.; Cunningham, M. Working in partnership: The challenges of working across organisational boundaries, cultures and practices. In Police Leadership: Rising to the Top; Fleming, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, B.C.; Farrington, D.P. Evidence-based crime prevention. In Preventing Crime. What Works for Children, Offenders, Victims and Places; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, A.A. Policing crime hot spots. In Preventing Crime. What Works for Children, Offenders, Victims and Places; Welsh, B.C., Farrington, D.P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eck, J.E.; Clarke, R.V. Situational Crime Prevention: Theory, Practice and Evidence. In Handbook on Crime and Deviance; Marvin, D.K., Hendrix, N., Hall, G.P., Lizotte, A.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Swizerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hope, T. Community crime prevention in Britain: A strategic overview. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2001, 1, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fledderus, J.; Honingh, M. Why people co-produce within activation services: The necessity of motivation and trust—An investigation of selection biases in a municipal activation programme in the Netherlands. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2016, 82, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M. Can government initiatives increase citizen coproduction? Results of a randomized field experiment. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2013, 23, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M.; Andersen, S.C. Coproduction and equity in public service delivery. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, J.; Croudace, R.; Pickering, J.; Lightowler, C. Building safer communities: Knowledge mobilisation and community safety in Scotland. Crime Prev. Community Saf. 2011, 13, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A.; Cherney, A. Prevention without politics? The cyclical progress of crime prevention in an Australian state. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2002, 2, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, M. Community safety, social cohesion and embedded autonomy: A case from south-west Dublin. Crime Prev. Community Saf. 2017, 19, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkin, D. Community safety partnerships: The limits and possibilities of ‘policing with the community’. Crime Prev. Community Saf. 2018, 20, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, T. The new local governance of community safety in England and Wales. Can. J. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2005, 47, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, T.; Van Ryzin, G.G.; Loeffler, E.; Parrado, S. Activating citizens to participate in collective co-production of public services. J. Soc. Policy 2015, 44, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, K. Responding to anti-social behaviour: Analysis, interventions and the transfer of knowledge. Crime Prev. Community Saf. 2011, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- de Graaf, L.; van Hulst, M.; Michels, A. Enhancing participation in disadvantaged urban neighbourhoods. Local Gov. Stud. 2015, 41, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.A.; Turchan, B.S.; Papachristos, A.V.; Hureau, D.M. Hot spots policing and crime reduction: An update of an ongoing systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Exp. Criminol. 2019, 15, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroozfar, P.; Farr, E.R.; Aboagye-Nimo, E.; Osei-Berchie, J. Crime prevention in urban spaces through environmental design: A critical UK perspective. Cities 2019, 95, 102411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisburd, D. Hot spots of crime and place-based prevention. Criminol. Public Policy 2018, 17, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, J.; Rhodes, R. Can experience be evidence? Craft knowledge and evidence-based policing. Policy Polit. 2018, 46, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggerty, K.D. From risk to precaution: The rationalities of personal crime prevention. In Risk and Morality; Doyle, A., Ericson, R.V., Eds.; Toronto University Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Armstead, T.L.; Wilkins, N.; Doreson, A. Indicators for evaluating community- and societal-level risk and protective factors for violence prevention: Findings from a review of the literature. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2019, 24, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butts, J.A.; Roman, C.G.; Bostwick, L.; Porter, J.R. Cure violence: A public health model to reduce gun violence. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.A.; Weisburd, D.; Turchan, B. Focused deterrence strategies and crime control: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Criminol. Public Policy 2018, 17, 205–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivert, A.; Mellgren, C.; Nilsson, J. Processutvärdering av Sluta Skjut. [A Process Evaluation to Stop Shooting]; Malmö Universitet: Malmö, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Corsaro, N.; Engel, R.S. Community-based crime reduction in Tulsa: An application of Petersilia’s multi-stakeholder collaborative approach to improve policy relevance and reduce crime risk. Justice Q. 2020, 37, 1199–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersilisa, J. Influencing public policy: An embedded criminologist reflects on California prison reform. J. Exp. Criminol. 2008, 4, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, E. Commentary on community safety in Germany. Crime Prev. Community Saf. 2011, 13, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recasens i Brunet, A.; Rodríguez Basanta, A. Development of the management of safety in Spain: Decentralisation with little organisation. Crime Prev. Community Saf. 2011, 13, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancey, G. A local case study of the crime decline. Safer Communities 2015, 14, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

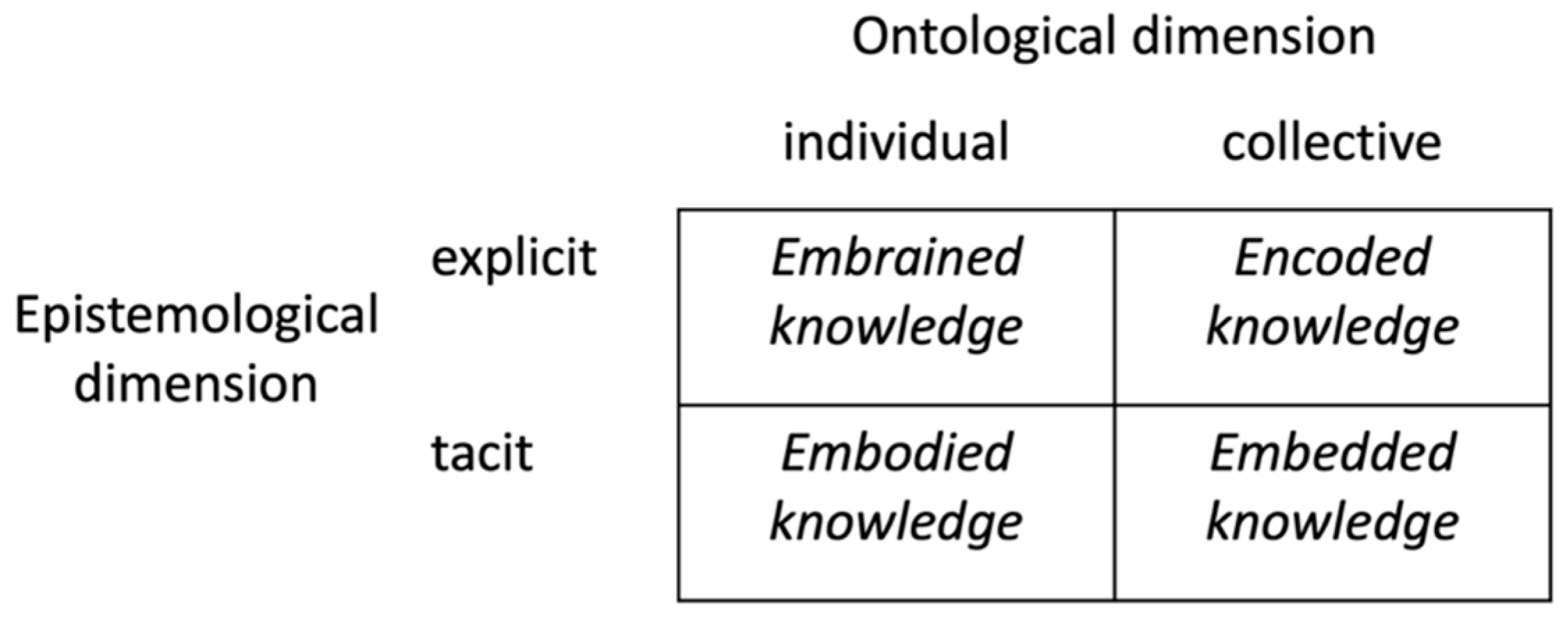

- Lam, A. Tacit knowledge, organizational learning and social institutions: An integrated framework. Organ. Stud. 2000, 21, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ocasio, W. Institutional logics. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; Greenwood, R., Ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, D. Project work: The legacy of bureaucratic control in the post-bureaucratic organization. Organization 2004, 11, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Ridderstråle, J. Adhocracy for an agile age. McKinsey Q. 2015, 4, 44–57. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com.proxy.lnu.se/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bsu&AN=112963953&site=ehost-live (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Mintzberg, H.; McHugh, A. Strategy formation in an adhocracy. Adm. Sci. Q. 1985, 30, 160–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. Administrative Behaviour; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, J.P.; Ungson, G.R. Organizational Memory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.S.; Duguid, P. Organizational learning and communities of practice: Towards a unified view of working, learning and innovation. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRÅ. Det Brottsförebyggande Arbetet i Sverige. Nuläge och Utvecklingsbehov. [Crime Prevention in Sweden: Present Situation and Development Needs]; Brottsförebyggande Rådet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Luitgaarden, G.M.J. Evidence-based practice in social work: Lessons from judgement and decision-making theory. Br. J. Soc. Work 2009, 39, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellgran, P.; Höjer, S. Forskning i Praktiken. Om den Seniora Forskningens Innehåll och Socionomers Forskningsorientering [Research in Practice. The Content of Senior Research and Social Workers’ Research Orientation]; National Agency for Higher Education: Stockholm, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, J.; Gear, A.; Jones, C.; Read, M. The child protection conference: A study of process and an evaluation of the potential for on-line group support. Child Abus. Rev. 2005, 14, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munroe, E. Common errors of reasoning in child protection work. Child Abus. Negl. 1999, 23, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkby, T.; Höjer, S. Navigations between regulations and gut instinct: The unveiling of collective memory in decision-making processes where teenagers are placed in residential care. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2011, 16, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alstam, K.; Forkby, T. Finding a Suitable Object for Intervention: On Community-Based Violence Prevention in Sweden. Societies 2022, 12, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12030075

Alstam K, Forkby T. Finding a Suitable Object for Intervention: On Community-Based Violence Prevention in Sweden. Societies. 2022; 12(3):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12030075

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlstam, Kristina, and Torbjörn Forkby. 2022. "Finding a Suitable Object for Intervention: On Community-Based Violence Prevention in Sweden" Societies 12, no. 3: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12030075

APA StyleAlstam, K., & Forkby, T. (2022). Finding a Suitable Object for Intervention: On Community-Based Violence Prevention in Sweden. Societies, 12(3), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12030075