Abstract

Many researchers and practitioners agree that a specific skillset helps to provide good healthcare to migrant and minority patients. The sciences offer multiple terms for what we are calling ‘diversity competence’. We assume that teaching and developing this competence is a complex, time-consuming task, yet health professionals’ time for further training is limited. Consequently, teaching objectives must be prioritised when creating a short, basic course to foster professionals’ diversity competence. Therefore, we ask: ‘What knowledge, attitudes and skills are most important to enable health professionals to take equally good care of all patients in evermore diverse, modern societies that include migrant and (ethnic) minority patients?’ By means of a modified, two-round Delphi study, 31 clinical and academic migrant health experts from 13 European countries were asked this question. The expert panel reached consensus on many competences, especially regarding attitudes and practical skills. We can provide a competence ranking that will inform teaching initiatives. Furthermore, we have derived a working definition of ‘diversity competence of health professionals’, and discuss the advantages of the informed and conscious use of a ‘diversity’ instead of ‘intercultural’ terminology.

1. Introduction

Societies are diverse. All members of societies are part of a multitude of collectives [1] (p. 196), [2,3] (p. 48) such as age group, sex, gender, sexual preference, education, profession, and workplace. People have different political orientations, phenotypes, worldviews, and spiritual orientations; belong to different lifestyle milieus, peer groups, etc. Everyone has certain habits of thinking, evaluating, feeling about, and doing things in daily life, and these might be related to the collectives of which one is a part. If people move ‘away from their place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border’ [4], they add—with their individual patchwork of identities [5]—to the diversity of their new social environment and even add a new collective, since they are now categorised and perceived as ‘migrants’ coming from a certain region or country of origin, with certain assigned or self-perceived structures of belonging, such as to a subgroup of that society, a religious tradition, or a language community. Each person undergoes a specific experience during transit, comes in a certain way and for specific reasons, fleeing from and/or striving towards something. In the case of transnational migration, everyone is additionally assigned a specific legal status with certain entitlements and restrictions, as well as possibilities to change this status [6] (p. 171), [7] (p. 1025). In accordance with socially constructed classifications of humans—such as the mentioned examples—people might be perceived and treated by fellow members of the host society in a specific way.

Many scientists and practitioners assume that special competences are needed to deal with the ‘differences’ that migrants add to societies in professional settings. Since societies are shaped by migration, ‘it is no longer possible to imagine debates on the requirement profiles of skilled workers’ without reference to ‘intercultural competence’, which ‘has become a much-used term and a central concept in a wide variety of practical fields’ [8] (p. 13). Educational, linguistic, psychological, economic as well as health sciences reflect on this competence and state demand for it (e.g., [9,10,11] (p. 490)). In the health sciences literature, there seems to be an understanding that a specific skillset is needed to meet the needs of all patients equally (cf. [12,13,14] (p. 225)). However, as in other fields (see [15] (p. 284), [16,17]; for an overview on concepts, see [18] (pp. 413–414)), there is no agreement on what to call this skillset, for example inter- or transcultural competence (e.g., [19,20,21]) or congruence [22,23], cultural competence [24], intercultural safety [25], and cultural humility [26]). There also is no consistency regarding specific skills the concepts include (cf. [27] (p. 45), [28] (p. 255).

The mentioned descriptors refer to ‘culture’, but the perceived and attributed dimensions of ‘differences’ within a diverse population exceed those that are framed as being ‘cultural’. The term ‘diversity competence’ points to a realisation that when we reflect on useful or even necessary professional competences in plural societies, we should consider the above-indicated multitude of collectives that all individuals are part of, and therefore the multitude of factors shaping their identities—be they those of a medical doctor or of a patient. However, ‘diversity competence’ also does not come with a common, agreed-upon definition (for a historical and analytical overview on the concept, see [29,30]).

If there is a need for a specific (professional) skillset within the health sector, the question is: What competences should health professionals possess to take good care of all their patients in evermore diverse, modern, differentiated, plural and democratic societies which include migrants and (ethnic) minorities? Additionally, since there are different concepts and potentially extensive lists of skills to be fostered: What are the most important skills to ensure everyone is being taken care of equally?

In order to address these questions, we want to report on a specific part of a Delphi study that was undertaken as part of a project, funded by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT-Health), called ‘Improving Diversity Sensitivity in healthcare—Training for health professionals’ (IMPRODISE). The project aimed to respond to the health-related challenges of an increasingly diverse European population by improving health professionals’ ability to deliver equitable care. It involved partners from Ghent University in Belgium, Heidelberg University Hospital in Germany as well as Hvidovre Hospital and the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. The research partners were aware that because of the multidimensionality of the topic and its complexity, intercultural or diversity competence courses regularly take a least a few days, often stretching over months [31] (p. 43). However, many health professionals have just one to six days a year allotted for continuing medical education [32] (p. 4). Moreover, they regularly work shifts and many hours, so they do not have much time, and appreciate flexibility [32] (p. 6). Thus, we aim at designing an eight-hour Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) for diversity sensitisation that meets the requirements of these adult learners in terms of compactness and flexibility.

To find out what the most important competences and therefore teaching objectives are, we wanted to explore how academic and professional experts in migrant health define diversity competence, especially regarding care for migrants and (ethnic) minority patients, and what competences they prioritise. The outcome of these questions will be reported here, and the results of the remaining study in a forthcoming article.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample Size and Selection of Experts

Data for this modified online Delphi study with two rounds were collected from 9 September 2020 to 10 January 2021. We invited experts who were likely to be able to contribute to the discussion from their specialist background and experience. Therefore, we aimed at including academic as well as practice experts in the field of migrant health and diversity. To be considered an expert, academic participants were to have diversity as a focus area of their scientific work, and to have published at least one academic article or taught a course related to diversity as the main topic. Health professionals were to have regular encounters in their daily work with migrant and ethnic minority patients. We also wanted our panel to be composed of experts working in various European countries. We used purposive and snowball sampling techniques to reach the desired composition of the panel. Academic experts were identified mainly through existing research networks related to migration and diversity topics, as well as through online searches. Health professionals were identified via networks of authors and project partners within clinical sectors: these professionals were asked to nominate two to four nurses, clinicians and registered physicians within their country who met our inclusion criteria. In each case, we also encouraged further referrals.

2.2. Expert Panel and Study Schedule

A total of 89 experts from 20 countries, including 50 academics and 39 health professionals, were identified as meeting our criteria, and were invited to participate via email. The invitation letter consisted of a brief outline of the project and its objectives, the number of rounds and an estimated time commitment, as well as a guarantee of anonymity of responses. Of the invitations, five went to invalid email addresses, 29 people did not respond to our invitation, and six people declined to participate. From the 49 experts who agreed to participate, 31 actually filled out the questionnaire (response rate 37%).

This final panel consisted of 18 academics and 13 health professionals, working in 13 European countries (see Table 1). Nine of the panellists had a migration background themselves (for more detailed socio-demographic data, see Supplementary Table S1). The majority had been involved in teaching activities on diversity topics (26) as well as in research (27) and had published on the topic. A total of 18 of the participants were or had been involved in providing medical care to migrant and ethnic minority patients.

Table 1.

Overview of the characteristics of the 31 participating experts (for full socio-demographic table—see Supplementary Table S1).

The experts received a link to the online survey containing a brief introduction, a description of the structure of this study, including relevant technical and organisational information, and a consent form, to agree on the usage of the gathered data in pseudonymised form. Analysis was performed anonymously, without matching personal information to the data. Professional affiliations were only subsequently assigned to the reported quotations and to analyse the response behaviour with regard to a single question (see discussion, p. 16). We allocated three to four weeks of response time for each round. To non-respondents, we sent weekly reminders after 10 days. Of the 31 experts participating the first round of the Delphi Study, 26 fully completed the second round. Three people partly filled out the second survey, another two did not respond to the final survey link and reminders.

2.3. Design and Analysis of Round 1: Collection of Most Important Diversity Competences

We started with a ‘classical’ qualitative round, meaning an open-ended question, to ‘generate ideas’ on how to define diversity competence, and gather comments on the panel’s understanding of the issue [33] (pp. 69–70). In reference to structural models of intercultural competence (e.g., [34] (p. 347), [35] (p. 23), [36], which are also widely agreed upon in the healthcare literature [37] (p. 120), we wanted to make sure that cognitive, affective, and pragmatic dimensions of diversity competence were considered, so we provided a simplified definition of those dimensions:

‘Diversity competence is most commonly described as consisting of three key dimensions: affective, cognitive, and pragmatic. The affective dimension includes what we want, what we think about things and people, how we feel and how we deal with these feelings. The cognitive dimension includes what we know, consider and reflect upon. The pragmatic dimension includes what we are able to do. With this in mind, what are—in your opinion—the three most important qualities/abilities/skills that a health professional should possess in order to provide good and diversity-sensitive healthcare, especially to migrant and ethnic minority patients?’

Content analysis of 106 generated statements was performed by SZ. Each analysis step was discussed with JS and CM. Firstly, statements that referred to similar topics were grouped together via copy and paste. Sometimes part sentences had to be grouped within different (and therefore two or more) categories. Afterwards, a summarising statement or category was assigned to each group. Secondly, the team collectively collapsed statements that carried the same meaning into one statement, trying to stay true to the most commonly used wordings of the panel [33] (p. 85). Unique statements were kept as worded. Categories and subcategories were refined using the new collapsed list of statements (ibid.). Condensing the statements into items, the round 2 questionnaire was created, which was structured according to affective, cognitive, and pragmatic dimension as well as the headline/category of the identified themes (see Table 2). Free-text comments elaborating on suggested items were also grouped under the categories and kept as full-text quotations to be provided to the panel under each item block in the round 2 questionnaire.

2.4. Design and Analysis of Round 2: Prioritisation of Diversity Competences

After gathering opinions as to what the most important diversity competences were considered to be, we categorised them. The category system (Table 2) in turn became the structure of the second-round questionnaire, which looked as follows:

Table 2.

Categorisation of first round content analysis.

Table 2.

Categorisation of first round content analysis.

| Affective Dimension | Number of Items |

|---|---|

| ATTITUDES | |

| 7 |

| 3 |

| AWARENESS | |

| 2 |

| 5 |

| 7 |

| 4 |

| Cognitive Dimension | |

| KNOWLEDGE | |

| 6 |

| 6 |

| 4 |

| 3 |

| Pragmatic Dimension | |

| SKILLS | |

| 3 |

| 1 |

| 4 |

| 3 |

| 2 |

| 4 |

| 3 |

| 2 |

A total of 65 items were generated for this second-round questionnaire (for the generated items of both rounds, see Supplementary Data S2; full-text elaborations that were also provided to the panel are omitted in the Supplementary to ensure anonymity). The questionnaire was pre-tested by, and discussed with, three academic and practice migrant health experts for refinement. The pre-testers were asked to assign a degree of unimportance/importance to the generated items on 6-point Likert scales. This turned out to be a challenging task since they considered all items to be important. Consequently, we presumed that panellists would also have a hard time rating items such as ‘open mindedness’ or ‘knowledge about the network of local actors’ or ‘listening’ to be unimportant competences. The added explanatory comments of colleagues would additionally remind participants that fellow experts had already deemed the suggested competences essential. We therefore decided to use a unipolar, fully verbalised 3-point scale for this part of the study, asking participants to rate only on the degree of importance (‘somewhat important’, ‘important’, ‘very important’).

After round 2, we descriptively analysed the data to show expert rankings and prioritisations, as well as consensus levels. In the Section 3, firstly we will provide a list of key competences deemed most important across all competence dimensions—for this purpose, we have calculated and ranked the mean (m) [33] (p. 90)—and we will also report the standard deviation (SD) to denote the homogeneity of responses. Secondly, we are interested in the level of agreement on the items within each competence dimension. There are different ways of measuring consensus [38]. To further prioritise content and, accordingly, to develop teaching objectives for a short course, we defined consensus on importance as 80% of participants either voting ‘important’ or ‘very important’. As an additional measure of central tendency, we also calculated the mode for each item, which represents the most frequently occurring value [33].

3. Results

Of all the competences that the group has suggested across competence dimensions, experts considered the following diversity competences (Table 3) to be the most important ones:

Table 3.

Highest ranked competences (according to mean value) across dimensions.

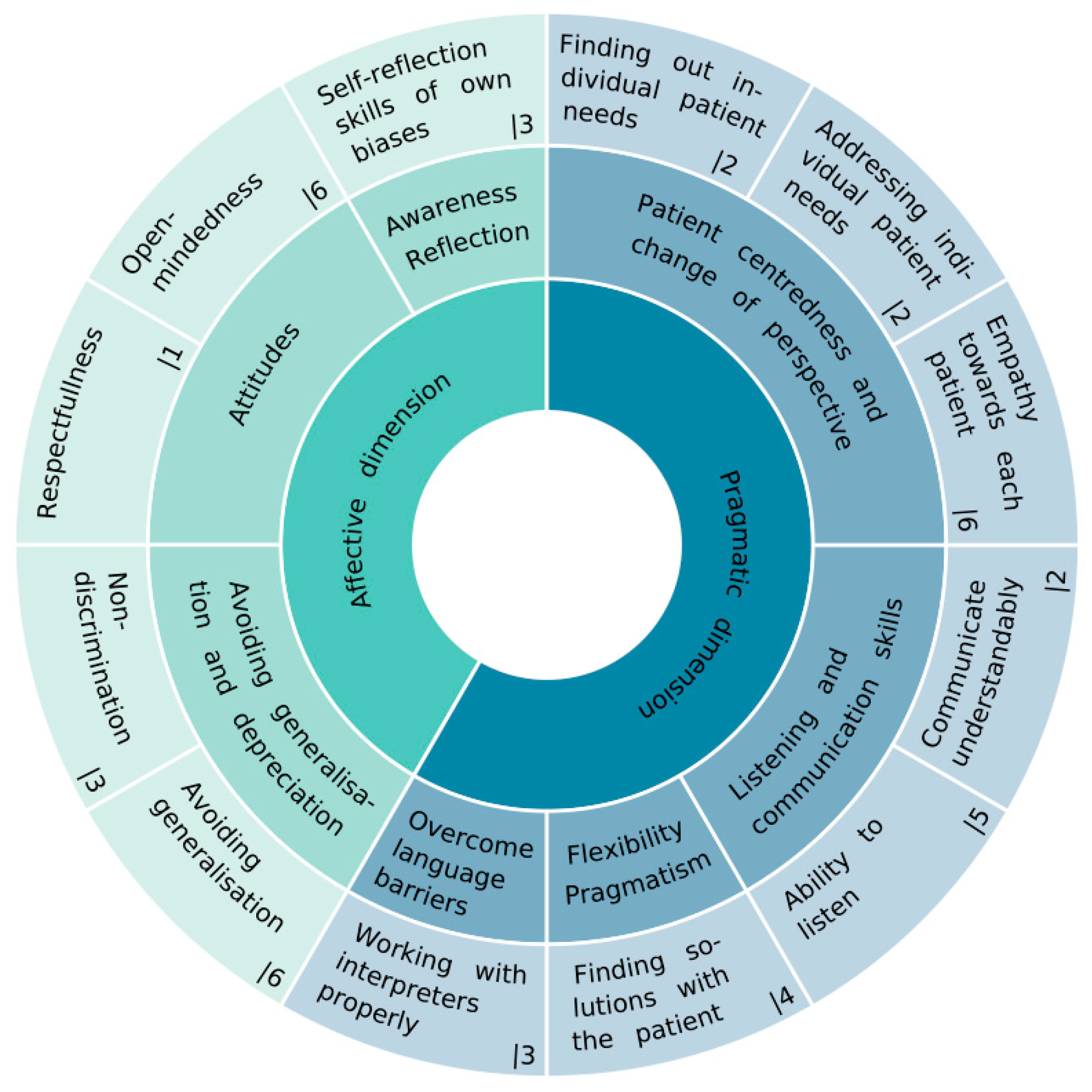

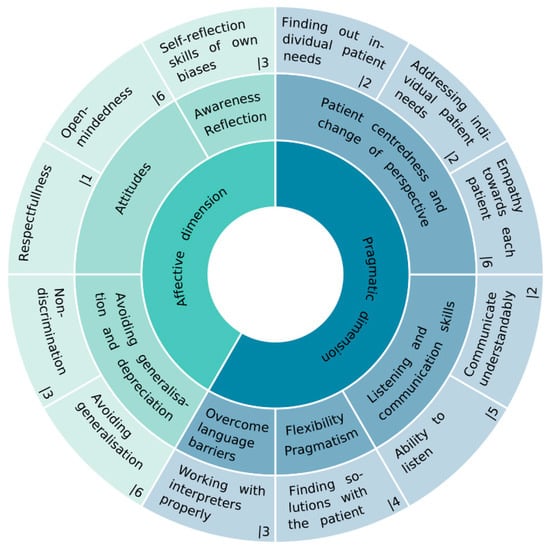

For nine of the 12 items on this list, we also observed the highest possible level of agreement, meaning 100% of the panel regarded them as either important or very important (see Supplementary Data S2 for full quantitative results). Only ‘non-discrimination’ and ‘avoiding generalisation’ received one and ‘open mindedness’ two ‘somewhat important‘ ratings. Assigning these highest-ranked competences to the respective categories and diversity dimensions shows that they are affective and pragmatic in nature, and no solely knowledge-based competence made this high-priority ranking list (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Highest-ranked diversity competences (rank number, see outer ring) according to mean value grouped by thematic categories and diversity dimensions.

Since the consensus of the experts is supposed to help us to prioritise competences and therefore teaching objectives, we will show further results using a ranking according to the level of consensus within each diversity dimension, occasionally accompanied by some expert comments on suggested items.

3.1. Affective Dimension

In the affective dimension, the panellists stated ‘attitudes’ they considered as defining for diversity-competent professionals. Additionally, self-reflective skills and the ability to avoid generalisation, prejudice and discrimination were considered as being significant in managing affects. One of the free-text suggestions depicts these themes:

In the affective dimension, the professional should be open-minded and be curious so [as] to allow them to learn from the patient, especially around health issues affecting patient’s life and how to solve them even when the strategies might be different from those of biomedicine. The first step is to be reflective and critical about [the] professional’s power position in relation to patients, and the second, the willingness to change(AER11)

Under the highest-ranking items according to consensus levels were ‘respectfulness’ and ‘self-reflection skills of own biases’ (also see key competences in Table 3). Several experts commented that being ‘aware’ of own prejudices was more important than trying to ‘avoid’ biases (especially in asymmetrical relationships). Another item, which did not already make the cross-dimensional mean ranking list (Table 3) was highly prioritised within the affective dimension, according to consensus level: ‘diversity awareness’, which experts explained like this:

Develop more understanding of the effects of the diversity dimension on conflicts, tension, misunderstandings, or opportunities(AETR1)

To gain information about the meaning of the diversity dimensions in the healthcare system (including: knowledge about Diversity Self-Awareness) […](AETR1)

None of the experts regarded this as only ‘somewhat important’, and it showed a slightly higher number of (just) ‘important’ ratings than the other two most highly prioritised competences shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ranking according to consensus in the affective dimension 1.

Three of the items in the affective dimension reached a consensus of 100%, 14 of the suggested items higher than 90%. Almost all the proposed items in the affective dimension reached our consensus threshold, in the sense that at least 80% of the experts considered them important or very important. Only regarding the items ‘courageousness’ and ‘compassion’ did opinions vary more widely. The former was explained by the panellist who suggested it (and therefore in the questionnaire) as ‘courage—to reach out to patients, see one’s own vulnerability and create a valuable relationship [that] can result in [an] encouraging encounter and be helpful in giving healthcare’ (AETR1). Here, approximately one-third of the participants voted for each importance option. Regarding the latter (‘compassion’), another panellist suggesting it defined it as ‘spreading wings of mercy to all patients’, which prompted a critical reaction from a colleague: ‘I do think we need empathy but not compassion, otherwise it means we are too close to the patient (HPR2)’.

When reporting the results of each competence dimension, we will also look at the outcomes within the thematic areas that all our items were previously grouped by (see category system, Table 2) and point to the most important (mean) and most disputed items (SD) within each thematic category. The most important attitudes were: ‘respectfulness’ and ‘open-mindedness’; the most disputed ones (according to deviation of opinions) were ‘politeness’ and ‘compassion’. Being able to leave one’s comfort zone was considered as important in the sense of being ‘ready to change the perspective towards empathy for the patient’ and to ‘admit there may be things we don’t know’ (HPR1); more disputed here was the necessity to be courageous. Diversity and cross-cultural awareness were agreed to be relevant; and of the proposed self-reflection skills, reflection on own biases and own power positions were considered most important. A little more disputed here (but still reaching a high level of agreement) was the necessity to reflect on own cultural health beliefs, own feelings, and own behaviour.

3.2. Cognitive Dimension

Regarding what professionals should know in order to provide diversity-sensitive healthcare, especially to migrant and ethnic minority patients, consensus was generally not as high as in the affective dimension. Mean values and standard deviation also show a higher variance of opinions (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Ranking according to consensus in the cognitive dimension.

The only item reaching 100% consensus, since all participants deemed it to be important or very important, was ‘knowledge about social determinants of health’; and of the two other items we considered as being part of a public health approach, ‘ethical and human rights competence’ was also highly prioritised by almost all panellists. Almost equally distributed between all answer options, and therefore more controversial, was the reaction to the necessity to demarcate the medical and political sphere, explained as: ‘evidence-based more than policy-based medicine’ (AETR1). However, of the structural factors that could be essential to know, ‘knowledge about the influence of policies on own field of activity’ ranked highest, followed by ‘knowledge on national legal contexts’, and the ‘network of local actors’ as well as ‘the asylum process.’

Regarding ‘knowledge on specific migrant-health differences’, the experts considered: ‘psychosocial stressors in exile’, ‘the influence of social exclusion and discrimination’ as well as ‘the influence of (forced) migration’ as most essential. Disease, treatment, and morbidity differences were not prioritised as highly.

The opinions on the relevance of knowledge about issues often summed up as ‘cultural’ aspects were a little more divided. Many experts agreed that knowledge on different belief systems as well as techniques to explore the patient perspective are relevant (see respective item * in Table 5). To carry out the latter, ‘clinically applied anthropology’ was proposed, meaning the utilisation of perspectives and methods of anthropology to explore the patients’ point of view. In connection to this, panellists suggested two texts, which we provided to the group to be rated via a ‘yes/no’ option as to whether health professionals should be familiar with them. The first was Kleinman and Benson’s ‘Anthropology in the Clinic’ (2006) [39]. Here, the authors warn against simplistic notions of intercultural competence which offer one-size-fits-all solutions and are prone to stereotyping, suggesting instead that professionals should find out what is at stake for patients and explore the patient perspective of their illness and therapy. A total of 24 (83%) of our experts agreed that health professionals should be familiar with this concept. Experts also proposed and rated the importance of being familiar with, secondly, the ‘Cultural Formulation Interview (DSM-5)’ [40], an interview guide that is supposed to help explore the influence of migration experience and the explanatory model of patients (developed and used especially in psychological settings): here, 23 experts (79%) voted diversity-competent health professionals should be familiar with this guide.

A further finding in the cognitive domain was that experts considered knowledge about different religions to be important, but this item did not reach consensus. There was even less agreement on the importance of knowledge about ‘cultures’ and of their critical and scientific study, which also did not reach consensus. Free-text suggestions and comments mirror these controversies: whereas someone states that knowledge on ‘broad cultural differences (individualistic vs. collectivist [orientations], influence of religion, importance of family role, shame and taboo)’ (HPR1) were important, other experts fully or partly disagreed:

Self-reflection (affective, cognitive and pragmatic) about social-cultural background, context and position (‘positionally‘) and not exclusively focusing on the ‘culture’ of the ‘other’!(AER1)

I have serious doubts if there is any useful knowledge on ‘cultures’, using the plural of this word and thus an essentialist concept of ‘cultures’ that can be described and distinguished one from the other. I think it’s important to talk about ‘culture’ yet problematic to talk about ‘cultures’ (the only useful way of doing this in teaching is probably by satire and irony for triggering reflection on stereotype etc.)(AER2)

3.3. Pragmatic Dimension

The statements and prioritisations in the pragmatic dimension received a higher level of agreement than in the cognitive dimension, with eight items reaching a consensus of 100% and four of higher than 90% (Table 6).

Table 6.

Ranking according to consensus in the pragmatic dimension.

According to means and consensus levels, the three most highly prioritised competences address individual communication and care. The first two items point to the importance of successful communication. All panellists regarded the ability to explain and provide information ‘in a way that this patient understands’ as important or very important. In addition, it was considered crucial to identify and address individual needs.

Communication skills are also important—both in listening as well as imparting information to others, including verbal and nonverbal communication. Poor communication can easily shut down or swing the focus of a healthcare encounter wildly off course—there are countless examples of this—and can delay diagnosis, lead to unnecessary investigations and/or inaccurate diagnoses, and thus harm the patient. Poor communication also makes healthcare encounters uncomfortable for health workers, and may influence the way they interact with patients from other ethnic or cultural backgrounds in the future.(HPR1)

Panellists stated diversity-competent health professionals should not only communicate understandably, but also in an open-ended manner, being aware of non-verbal cues, whereas using ‘non-verbal signals’ was not endowed with the same level of importance. In overcoming language barriers professionally, half of the experts regarded ‘language skills’ as only ‘somewhat important’. ‘Working with interpreters properly’ and ‘knowing the pitfalls of using ad hoc and lay interpreters’ were seen as much more important. Furthermore, many panellists had suggested that the ‘ability to listen’ was essential for diversity sensitivity (here only a few examples):

In the pragmatic dimension, professionals should listen instead of asking and talking all the time(AER1)

Communication: listening, creating a bearing/empathic/attentive relationship to patient and relatives(AER1)

The art of listening has been lost, in the development of cultural competence listening is basic(AER1)

Asking patients actively about their understanding of the disease and therapy as well as addressing related conceptual differences were seen as significant by many (and reached consensus). For this item, the field of opinions was spread more broadly than for the previous items. There was some discussion about proactive cross- and transcultural enquiries. Some believed to conduct such enquiries could be too much to ask from health professionals and it could ‘be perceived by patients as embarrassing or transgression’ (AER2); active listening would in most cases be sufficient. Another panellist also stated that addressing ‘concepts’ of disease and related differences might overstrain professionals and suggested they should instead use Kleinman’s approach to explore explanatory models, using some simple questions (AETR2).

Regarding change of perspective and patient centredness, as mentioned above, individual needs assessment and care received an overwhelming level of approval. Empathy was considered as an important or very important basis for pragmatic skills by the panel.

All […] attributes […] should ideally be informed by empathy: an ability to put yourself in the other’s shoes, no matter who they are(AER1)

Regarding a holistic understanding of the patient within his/her contexts and collectives, there was also much agreement, but most participants voted for the middle category ‘important’:

Rather than relying exclusively on a preconceived knowledge about patients’ assumptions and expectations, professionals should develop a critical thinking in order to be able to recognise and reflect upon the unique experience of the patient based on the dynamic intersection of factors which are generally not lived in isolation, and to respond to them in an integrated and comprehensive way(AER1)

To see the patient as an ‘individual’, while keep in mind that group dynamics and belonging to a particular (cultural/ethnic) group can affect ‘individuality’(AETR1)

To leave his rationality and try to understand the needs, the problems, the world of the person(AETR1)

Ability to understand patients’ context and sociocultural representations. Knowing the immigrant patient involves their daily life, the difficulties faced, the supportive environment they have and what is significant in their health from their individual and cultural perspective(HPR1)

No consensus was reached for ‘spiritual care’ and/or referral by the health professionals—64% of the panellists considered this to be only ‘somewhat important’. The panel also discussed if diversity sensitivity also meant identifying and addressing traumatic experiences. Consensus was reached, but panellists were aware that

- (1)

- it ‘is very important but also a very delicate issue’ (AER2) and

- (2)

- it ‘is important as long as the patient demands help or agrees to be helped by the professional. Caution should be exercised because not all people who have suffered trauma, whether or not linked to the migration process, want to relieve and share it’ (HPR2).

Regarding a ‘pragmatic’ attitude in the literal sense, the panel regarded it as essential to find solutions together with the patient, which fits a patient-centred care objective. It was also considered good to be flexible and adaptive. Sometimes improvisation is also needed, but there was no consensus on this ability.

3.4. Structural Competence: An Issue Cutting across All Diversity Dimensions

The panellists were asked to refer to knowledge, attitudes, and skills in their suggestions for the most relevant diversity competences, yet they expanded this common conception of competence—ultimately focused on individuals and their capabilities to deal with diversity and difference in interactions—to include structural aspects. Throughout the competence dimensions, we found references to structural aspects, beginning with, for example, a comment that communicative difficulties might not only occur because of lacking language proficiency, but might ‘even’ be linked to ‘institutional issues’ (AETR1); and there were suggestions about including reflections on the ‘situation and context’ of patients, when trying to understand what happened in an interaction (HPR1). Panellists also pointed to the importance of knowledge on legal and policy issues, which influence or even make up the context of migrant and minority patients’ lives:

Structural Factors and Public Health Approach: To know how the administrative situation of the immigrant in the host country (legal or illegal) influences his/her health status, due to the numerous socio-economic conditions, and to know what these are(HPR2)

Another expert stated that a caring, open attitude and attempts to understand strategies deviating from bio-medical ones should be based on the willingness to reflect upon one’s own professional and societal power position (HPTR2). The following quotations also point to such a reflection:

[…] The first step is to be reflective and critical about [the] professional’s power position in relation to patients(AER1)

[Reflection on] various forms of abuse of power (conscious and/or unconscious), paternalism and any other form of imbalance of power in the relationship between health professionals and patients(HPR2)

Power asymmetries between doctors and patients, professional helpers and those in need, representatives of a majority and a minority, citizens and non-citizens, scientists, and laypeople (see further examples [41] (p. 781), [42] (168, 172)) should therefore be considered in attempts to explain incidents in interactions that deviate from one’s own conception of normality. According to our panel, further structural factors to be addressed regarding diversity competence are individual and societal forms of exclusion and devaluation of migrants and minorities:

Self-reflection […] including individual and structural racism(AETR1)

[Knowledge on] the influence of social exclusion and discrimination(HPR1)

4. Discussion

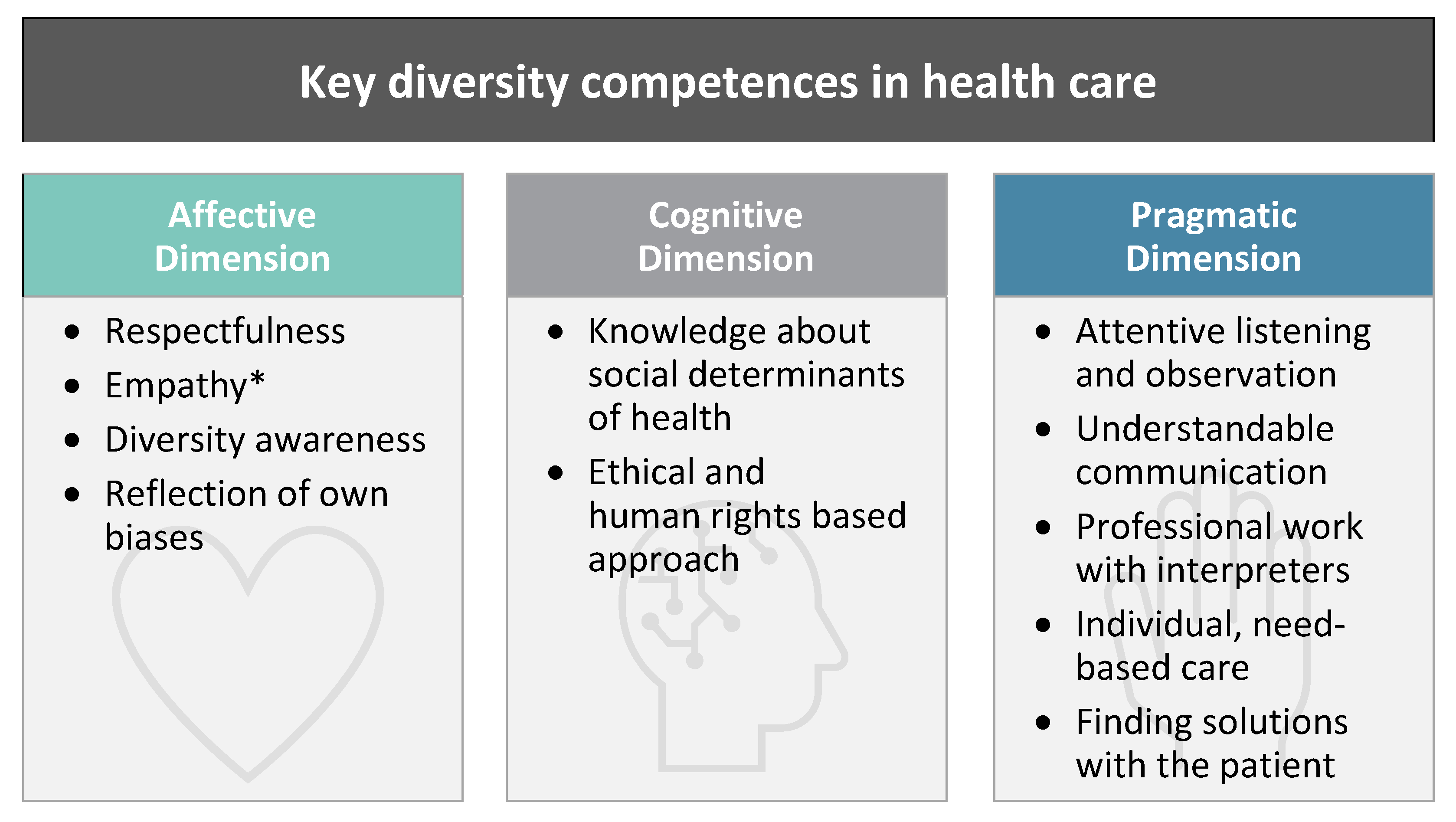

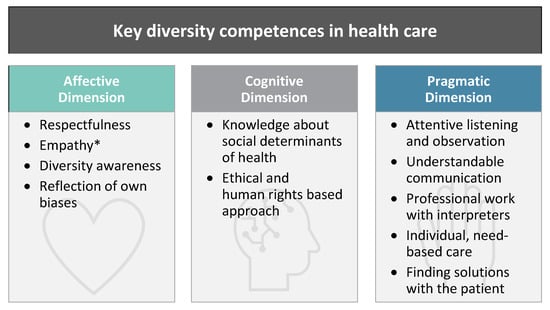

Diversity competence is not just an additional competence but can be seen as a ‘special qualification’ which enables professionals to fulfil the general requirements of their profession in complex situations and interactions with a super-diverse patient population. Leenen et al. similarly made this point for intercultural situations [43] (p. 117). They deduce that every practice setting requires a correspondingly adapted competence profile [8] (p. 20). Intercultural or diversity competence models in the health sciences sector are often based on literature reviews within the health sciences and on authors’ personal experiences; few conceptual models have been made based on ‘leading expert opinions’ or ‘methods such as Delphi’ [37] (e124). We used this method to specify a diversity competence profile for the health sector and prioritise its content. To that end, we asked migrant health experts to state the most important diversity competences for health professionals working with migrant and minority patients. Since many competences suggested and rated by our panel received a high level of approval, to sum up, we will only consider those that reached the highest levels within each competence dimensions to derive a minimal (!) definition of essential diversity competences:

Diversity-competent health professionals respect their patients and are aware of the wide variety of possible attributes and collective memberships that all participants bring to a healthcare encounter. They can reflect on their own biases and strive towards equitable treatment, applying an ethical, human rights-based approach. Their competence also includes knowledge on social determinants that can affect the health of their patients. Diversity competent health professionals can communicate understandably and are empathetic listeners, who identify and address the individual needs of each patient and find solutions together. If necessary, they are able to work with interpreters in a professional manner.

This minimal definition contains basic elements, such as respect, empathy, awareness, self-reflection, and communicative skills that are known from other diversity and cultural competence definitions in healthcare (cf. [44,45]). However, our high-threshold definition is supplemented by aspects that are of particular relevance in the medical setting (see Figure 2)—firstly, that knowledge about social determinants of health should be linked with diversity considerations. This is in accordance with the findings of a similar Delphi Study, addressing medical teacher competences [46]. Secondly, to also foster an ethical and human rights-based professional practice while addressing diversity competence in healthcare settings, any training needs to remind people of their (professional) ethics.

Figure 2.

Key diversity competences. (* Empathy: in this summary, categorised as ‘affective’, formerly—in the questionnaire—assigned to the pragmatic dimension, within the ‘category patient centeredness and change of perspective’).

‘Respect’ can already be considered an ethical principle—which includes assigning ‘equal moral worth’ to everyone, so everyone ‘deserves’ equal and substantial respect’ [47] (p. 218). Two (of the four) healthcare ethics principles—autonomy and justice [48]—are of particular importance regarding diversity-sensitive care. Autonomy not only means respecting autonomous choices of patients, but also exploring their perspectives, preserving ‘their dignity and moral agency’ and seeing them as ‘equal partners in healthcare encounters’ [47] (p. 219). Respectful treatment in that sense should be linked to justice. A widely accepted justice concept is that of non-discriminatory care (ibid.): physicians have sworn not to permit ‘considerations of age, disease or disability, creed, ethnic origin, gender, nationality, political affiliation, race, sexual orientation, social standing or any other factor to intervene between [their] duty and [their] patient’ [49]. The respective suggestions of the panel show that diversity training should not be seen as a new, stand-alone, extraordinary, or exotic topic, but can and should be linked to such relevant socialisation content within the respective professional context. To link diversity considerations with professional ethics might also help boost the credibility of and relevance attribution to soft-skills training of the sort that is discussed here. Our panel also proposed a human rights-based approach as an additional normative frame for diversity education. There already is some discussion of human rights education in the health sciences [50] and we found examples of related teaching and advocacy initiatives [51,52,53,54]. Such approaches have a normative, but also a legal, component which can be of significance for decision making and advocacy in caring for migrant patients (e.g., with respect to victimhood of torture in refugee medicine or female genital mutilation). There are conceptual and didactical examples that already integrate human rights education with intercultural and diversity training in nursing [55] as well as in social work (see, e.g., the Social Justice and Diversity approach: [56,57]), which can inspire training conceptualisation.

Whereas our study shows that diversity and cross-cultural awareness are seen as important by a majority of experts, acquiring knowledge on religions (69%) and especially on cultures (57%) did not reach a consensus level of over 80%. Here, the sentiments of our panel seemed to be divided between the recognition of a need for information to foster understanding, and the assessment that such inquiries and analysis are tricky tasks and should only happen in a condensed and clinically relevant way. In a Swedish Delphi-study on core ‘cultural’ competences in nursing, knowledge acquisition on ethnic and cultural identities of patients also did not reach consensus [58] (p. 2631), whereas an American qualitative study found that most of the participating health professionals (who considered cross-cultural training as being important) suggested learning about different cultures and customs should be included [59] (p. 135). However, the majority of our panel favoured looking at individuals, their perspectives and their specific needs, instead of extensive knowledge acquisition about ‘cultures’ in general; moreover, they suggested that health professionals should engage in various kinds of self-reflection. This is in line with aspects of individualised, patient-centred care [60,61] and corresponds to the current state of research regarding (trans)cultural competence, where the gaze is no longer strongly directed towards the others and their otherness, but a more procedural, individualistic and (self-)reflexive standpoint is taken (see, e.g., [46] (p. 72), [62,63]). One hypothetical explanation for contradictory findings could be found in the panel compositions. An overwhelming number (23) of our panellists identified as researchers or academic experts. Eight panellists identified as ‘teachers’, with four as ‘diversity trainers’ themselves2. The mentioned development away from potentially essentialist approaches [64], towards transculturality in pedagogical, cultural and social sciences might have ‘reached’ academic experts earlier than professionals with mainly practical daily routines. Our panel was—like the Swedish one—a mix of academic and practice experts, but only four of our 18 practitioners identified as being solely clinically involved. A look into the data shows that three of the four clinicians considered ‘knowledge about different cultures’ as important, one as ‘very important’; yet only one other person in a medical administrative position shared this last assessment, with almost all of the teaching academic experts (7 of 8) in this round giving this form of knowledge the lowest priority. Since our sample is small and many of the professional affiliations overlap, further research would be needed to explore whether medical practitioners tend to appreciate being presented with concrete ‘knowledge’ about cultural habits of people of specific origin. In an increasing number of academic disciplines, such ideas are deconstructed as useless or even harmful. To explore the expectations of course participants and consciously reject some of them might be worthwhile, since any training has to strategize how not to foster the stereotypical imaginations it set out to fight (cf. [8] (p. 27), [65]).

Generally, we observed a higher level of disagreement on knowledge content than on the importance of affective and especially pragmatic objectives. This finding not only helps to prioritise content, but it might also imply that ‘knowledge’ is considered as less important overall than, for instance, attitudes, reflection skills and to a certain extent practical skills. However, knowledge would be the easiest to prepare and present in a digital format. In the pragmatic area, we can provide exercises—for example to practise communication strategies—and we can offer recommendations for action and invite people to implement in their daily routines what they have learned during the training. Regarding the affective competences, there is some debate as to whether these can in fact be trained. One of our panellists commented on his/her rating decisions in the affective dimension, stating he/she had rated the importance of certain objectives lower, since they were ‘extremely difficult to teach (e.g., curiosity)’ (AETR2). This points to the fact that diversity competence—like intercultural competence—is an occupational-professional as well as personal quality cf. [43] (p. 114)3. This means that while some competences can be trained, others will be harder to achieve without a personal/ity predisposition [66]. In face-to-face training games, role-play and simulations are used to allow for relevant ‘feelings’ to come up (e.g., [67,68,69]), get used to and be reflected upon. This might be harder in a digital format. There is research on technology-enhanced role-play [70], but until something like that is publicly accessible, we might still be able to trigger effects such as uncertainty or resentment through multi-media content such as video clips, aiming to deconstruct negative emotional triggers, normalise feelings and make them reflexively accessible; or we could stimulate empathy using methods such as case work. However, often used critical incidents (e.g., failed interactions or misunderstandings; see [71]) will only be used by us to invite participants to create multiple, multi-layered interpretations of situations, without providing ‘right’ answers. All such efforts have to be accompanied by an individual guided, structured reflection to be effective (as performed by, e.g., Zembylas [72]). Finally, there is room for optimism regarding training endeavours, since the division into affective, cognitive, and pragmatic competence dimensions is somewhat arbitrary, because they are interdependent or interpenetrated in everyday actions and we will connect the training to these everyday experiences. With Bolten, we understand diversity competence as the product of a synergetic interplay of the sub-competences [35] (p. 24), which should all be addressed, but not necessarily separately.

With regard to intercultural competence, there is debate as to whether we are dealing with a special set of skills at all, or just general social or action competence applied in intercultural settings [35] (pp. 23, 27), [73,74] (p. 109). How special this set of skills is, can also be asked about what our experts considered ‘diversity competence’ to be. Most suggested abilities might be useful for communication between people of different languages or origins, different generations, social milieus, professional or scientific communities, etc. Except for language proficiency or translation, all abilities are useful in any social situation. As soon as we recall that diversity is nothing extraordinary, but is simply normal in societies, the question of the specificity of diversity competence becomes even more interesting and hard to answer. But what we can already say is that (1.) the changing demographic and transcultural landscapes have implications for health systems (see [19] (pp. 19–20); and there is (2.) ‘a consistent gap between minority and majority populations in terms of health outcomes’ (for instance the mortality in relation to certain diseases differs according to skin colour, see studies referred to by [75] (p. 188). (3.) Migrant and minority patients are often less satisfied with their health system encounter (e.g., [76,77]); and (4.) health professionals often describe their daily work with migrant patients as challenging ([78] (pp. 7–11), [79] (p. 9), [80] (pp. 3–7), [81] (p. 38)). Thus, it makes sense to consider how these challenges can be successfully met. Which terminology is used to discuss and practise strategies for action is beside the point, but we see some advantages in the—not interchangeable, but conscious—use of the diversity terminology over concepts of intercultural competence.

Firstly, the narrow focus on ‘natio-ethno-cultural membership’ [82] becomes broadened. Especially in the context of migration, ‘culture’ is still mostly ascribed to national, religious, or ethnic collectives. Not enough attention is paid to the fact that any human is part of a multitude of collectives, including for example social and legal status, spatial, leisure, and professional milieus. Each collective develops a multitude of habits (which can be called ‘culture’) [3]. But as long as we do not yet assign culture to any human collective, the diversity terminology seems more suitable than ‘intercultural’ terms. Additionally, there are outdated, essentialist concepts of culture in circulation that imply homogeneity of for example a ‘group’ of people of this or that nationality or religion. But cultures are heterogenous, permeable and overlapping and without clear boundaries; they are dynamic, and oftentimes ‘fuzzy’ (cf., e.g., [3,83,84]). At least as long as such non-essentialist, constructivist concepts of culture have not yet gained widespread acceptance, we would rather talk of ‘diversity’, since this term evokes the appropriate associations of plurality, hybridity and multi-collectivity.

Furthermore, since diversity competence can be seen as the ability ‘to normalise strangeness of any kind in interactions’ [85] (p. 76), all patients, not only migrants and minorities, can benefit from professionals who realise that plurality is normal in modern societies. All patients can benefit from professionals who consider each patient’s identity as a unique, multi-collective assemblage. Everyone benefits from professionals who are able to explore these individual identities, reflect upon them and take into consideration what aspects are relationally and/or medically relevant.

Secondly, diversity competence concepts not only point to the opportunity of explorations for the sake of the identification of health needs and concerns and as a basis for supportive relationships, diversity concepts also come with a pragmatic management focus fostering conscious organisational and institutional development towards inclusive procedures and structures such as simplified bureaucracy, diverse workforce or regular access to professional interpreting services in healthcare organisations (cf. [12] (p. 296), [75] (pp. 185, 187), [86]). Diversity considerations can help to identify and tackle organisational or institutional barriers of specific patient collectives.

Thirdly, diversity considerations should incorporate an awareness of contextual and structural aspects that (might) influence patients’ scope for action, identities, lives and health in significant ways (see similarly [87]), therefore scientific linkages with equity perspectives present themselves. Diversity considerations should be integrated with a focus on social determinants of health [88], for example when considering diverse living conditions of migrants and minorities. They also invite an extension towards a ‘sensitivity to the influences of power asymmetries and collective experiences’4, which Auernheimer has already conceptualised as a necessary extension of intercultural competence [89] (p. 118). Anti-oppressive thinking and practice would be part of such an approach [18,90,91]. When looking at ‘policies, economic systems, and other institutions (judicial system, schools, etc.) that have produced and maintain modern social inequities as well as health disparities, often along the lines of social categories […]’ [92] (p. 55), we see the opportunity to link and integrate public health reflections on various structural (‘downstream’ and ‘systemic’) factors with the diversity competence concept, since it grasps multiple social categories. In line with our panel’s suggestions, we intend to foster structural competencies in their own right [93,94] and offer a diversity perspective which combines the awareness and recognition of multi-collectivity with a reflection on social determinants of health, structural factors including power asymmetries, as well as social relations of inequality and discrimination [95] (pp. 184–185).

5. Limitations

We do not claim that our expert panel’s prioritisations are representative, since we performed a selective sampling of participants, and the results from our Delphi study could be specific to this panel. On many aspects, consensus was reached in the Delphi sense, but further research with larger samples would be needed to validate the results. In the course of such research, it would also be advisable to ask patients for their opinion on the topic.

Comparisons regarding the response behaviour of academic versus practice experts at first seemed interesting, but due to the composition of our panel, it would not have been sensible, since professions and affiliations overlapped, and we could not distinctly distinguish between the groups. Because we achieved a high degree of agreement, we consider the compilation of results as sufficient. The open-ended approach of our study was pre-structured by three given diversity competence dimensions that experts were asked to address; we also limited the number of items that should be mentioned, forcing prioritisation, but taking away the possibility of a completely free formation of expert opinion. There is also the possibility of bias through other parts of the comprehensive questionnaire that were not reported on here: many topics and comments might not have come up in the second round of the part of this study reported here, because participants worked through an extensive list of standardised items, rating pre-given training objectives and content in round 1 before being asked to rate their own (open-ended) suggestions on most important competences again in round 2. Furthermore, the decision to use a 3-point scale, which we made after pre-testing the questionnaire, was explained with social reasons for valuing all priorities of our experts as such. The high measures of central tendency and consensus show that this decision was justified. However, we have withheld the possibility of declaring the suggestions of others as unimportant. Additionally, from a statistical point of view, the 3-point scale limited analytical possibilities. Since the larger part of this study worked with items to be rated that had already been standardised, two rounds seemed sufficient and more efficient (cf. Jenkins 1994), even if the open-ended question presented here about important diversity competences could have profited from a third survey round to foster discussions.

6. Conclusions

Academic and health professionals provided their opinions regarding key diversity competences of health professionals. After qualitative and quantitative analyses, our findings allow for the prioritisation of teaching objectives, and we were able to provide a minimal definition of diversity competence, specified for the health sector, linking it to the existing public health discourse on social determinants of health, and structural factors, as well as to healthcare ethics and human rights.

We have discussed some advantages of the term ‘diversity competence’: it allows for a thematisation of individual conditions of the possibility of successful professional encounters in the face of multiple perceived and constructed differences. It is conceptualised as a more general competence than intercultural competence, one which applies to interactions with all patients, not just a specific group of foreigners. Migration background becomes one of many dimensions of differentiation, thus normalising difference.5 Scientifically interdisciplinary inquiries can be fostered and linkages to other concepts such as social determinants of health can be initiated, and in practice contexts not only individual training, but also organisational development with a diversity management focus can be thematised. The diversity terminology is open to incorporating contextual and structural aspects. Societal and political structures, decisions and actions that put people in harm’s way [96] (p. 1686), that prevent them from achieving the highest level of health attainable to them (International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Art. 12 [97]) or hinder the delivery of accessible and equitable healthcare provision to all people can also be addressed within the frame of diversity considerations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/soc12020043/s1, Table S1: Characteristics of participants (full socio-demographic table); Data S2: Generated items and quantitative results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.Z.; methodology, S.Z.; software, C.M.; recruitment, S.Z., C.M. and J.S.; formal analysis, S.Z.; investigation, S.Z., C.M. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.M., J.S.; visualisation, S.Z.; supervision, J.S.; project administration, S.Z., J.S.; funding acquisition, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was part of the IMPRODISE project (Improving diversity sensitivity in healthcare). It was funded by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology, EIT Health, grant number 20520.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the Danish Act on the Biomedical Ethics Committee System and the Processing of Biomedical Research Projects, the study was not notifiable to the Danish Research Ethics Committee System, as it did not include biological material. All potential participants received written information about the study underscoring study objectives, anonymity procedures, participants’ rights to withdraw and that (non-)participation had no consequences for the individual. Data was handled in full accordance with the requirements defined by the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects involved in the study were informed and consented actively in digital form.

Data Availability Statement

Further information on data is available on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank our student assistants Diana Meyer (Heidelberg University Hospital) and Julie Marie Møller Olsen (University of Copenhagen) for their help with data management. We also thank Julie Dyson for English language revision within this article, and for taking the time to discuss optimal phrasing with us. Many thanks to Kayvan Bozorgmehr (Section for Health Equity Studies & Migration, Heidelberg University Hospital) for accepting the study as part of the research agenda of the Section and for his valuable input on the manuscript. Many thanks also to Allan Krasnik (Danish Research Centre for Migration, Ethnicity and Health, Section for Health Services Research, University of Copenhagen) for supporting the funding acquisition and his input on questionnaire development.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the following: the design of the study; the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | Pseudonyms only refer to professions and rounds, without individual assignment: HP = Health Professional, AE = Academic Expert (AET, in case the AE is additionally a diversity trainer or teacher); statements from Round 1 = R1, from Round 2 = R2. |

| 2 | Multiple answers possible regarding the current job position. |

| 3 | ‘It is a spectrum of complex abilities that are more or less closely bound to the person, which in part can only be influenced to a limited extent by educational offers or can only be initiated as a learning process by the subject himself’ (Leenen et al., 2013, p 114; own translation). |

| 4 | He mentions experiences of discrimination and after-effects of colonial history as examples (Auernheimer 2013, p 118). |

| 5 | The real goal of diversity competence training is to reach a level of normalisation in dealing with perceived and constructed differences, thereby making acts of naming, and reflection on diversity obsolete. |

References

- Hansen, K.P. Kultur und Kulturwissenschaft; UTB: Paderborn, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, K.P. Kultur, Kollektivität, Nation; Stutz: Passau, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rathje, S. The definition of culture: An application-oriented overhaul. Intercult. J. 2009, 8, 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration. Who Is a Migrant? Available online: https://www.iom.int/node/102743 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Keupp, H. Identitätskonstruktionen: Das Patchwork der Identitäten in der Spätmoderne; Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verl.: Reinbek, Germany, 2008; ISBN 978-3-499-55634-0. [Google Scholar]

- Vertovec, S. Towards post-multiculturalism? Changing communities, conditions and contexts of diversity. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2018, 68, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vertovec, S. Super-diversity and its implications. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2007, 30, 1024–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, T. Von Interkultureller Kompetenz zu Vielfaltskompetenz? Zur Bedeutung von Interkultureller Kompetenz und möglicher Entwicklungsperspektiven. In Handbuch Diversity Kompetenz: Band 2: Gegenstandsbereiche; Genkova, P., Ringeisen, T., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; pp. 13–31. ISBN 978-3-658-08853-8. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, D.K. Intercultural competence: Mapping the future research agenda. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2015, 48, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.-Z.; Zhu, C.; Wu, W.-P. Visualizing the knowledge domain of intercultural competence research: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2020, 74, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.; Ang, S.; Tan, M.L. Intercultural Competence. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 489–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Betancourt, J.R.; Green, A.R.; Carrillo, J.E.; Ananeh-Firempong, O. Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003, 118, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campinha-Bacote, J. The Process of Cultural Competence in the Delivery of Healthcare Services: A model of care. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2002, 13, 181–184; discussion 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, S.; Kendall, E.; See, L. The effectiveness of culturally appropriate interventions to manage or prevent chronic disease in culturally and linguistically diverse communities: A systematic literature review. Health Soc. Care Community 2011, 19, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, D.K. Intercultural competence: An emerging focus in international higher education. In The SAGE Handbook of International Higher Education; Deardorff, D.K., Ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 283–304. ISBN 978-1-4129-9921-2. [Google Scholar]

- Fantini, A. Assessing intercultural competence: Issues and Tools. In The Sage Handbook of Intercultural Competence; Deardorff, D.K., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 456–476. ISBN 1412960452. [Google Scholar]

- Auernheimer, G. (Ed.) Interkulturelle Kompetenz und Pädagogische Professionalität, 4th ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; ISBN 9783531199306. [Google Scholar]

- Danso, R. Cultural competence and cultural humility: A critical reflection on key cultural diversity concepts. J. Soc. Work 2018, 18, 410–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreachslin, J.L.; Gilbert, M.J.; Malone, B. Diversity and Cultural Competence in Health Care: A Systems Approach; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fleckman, J.M.; Dal Corso, M.; Ramirez, S.; Begalieva, M.; Johnson, C.C. Intercultural Competency in Public Health: A Call for Action to Incorporate Training into Public Health Education. Front. Public Health 2015, 3, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bjarnason, D.; Mick, J.; Thompson, J.A.; Cloyd, E. Perspectives on transcultural care. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2009, 44, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leininger, M.M. (Ed.) Culture Care Diversity and Universality: A Theory of Nursing; National League for Nursing Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 0887375197. [Google Scholar]

- Schim, S.M.; Doorenbos, A.Z. A three-dimensional model of cultural congruence: Framework for intervention. J. Soc. Work End Life Palliat. Care 2010, 6, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharifi, N.; Adib-Hajbaghery, M.; Najafi, M. Cultural competence in nursing: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 99, 103386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, E.; Jones, R.; Tipene-Leach, D.; Walker, C.; Loring, B.; Paine, S.-J.; Reid, P. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervalon, M.; Murray-García, J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 1998, 9, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handschuck, S.; Schröer, H. Interkulturelle Orientierung und Öffnung: Theoretische Grundlagen und 50 Aktivitäten zur Umsetzung, 1. Aufl.; ZIEL: Augsburg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 9783940562708. [Google Scholar]

- Rathje, S. Intercultural Competence: The Status and Future of a Controversial Concept. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2007, 7, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vertovec, S. ‘Diversity’ and the Social Imaginary. Eur. J. Sociol. 2012, 53, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolten, J. “Diversität” aus der Perspektive eines offenen Interkulturalitätsbegriffs. In Interkulturalität und Kulturelle Diversität; Moosmüller, A., Möller-Kiero, J., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 47–60. ISBN 978-3-8309-2998-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, M. Interventions to promote learners’ intercultural competence: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2019, 71, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien Pott, M.; Blanshan, A.S.; Huneke, K.M.; Baasch Thomas, B.L.; Cook, D.A. Barriers to identifying and obtaining CME: A national survey of physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, S.; McKenna, H.; Hasson, F. The Delphi Technique in Nursing and Health Research; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 9781405187541. [Google Scholar]

- Gertsen, M.C. Intercultural competence and expatriates. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1990, 1, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolten, J. Was heißt “Interkulturelle Kompetenz?”: Perspektiven für die internationale Personalentwicklung. In Wirtschaft Als Interkulturelle Herausforderung: Business across Cultures; Künzer, V., Berninghausen, J., Eds.; IKO-Verl. für Interkulturelle Kommunikation: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2007; pp. 21–42. ISBN 3-88939-849-9. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, S.; Gelbrich, K. Interkulturelles Marketing, 2nd ed.; Franz Vahlen: Berlin, Germany, 2015; ISBN 9783800644612. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, S.; Chavan, M. Cultural competence dimensions and outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Health Soc. Care Community 2016, 24, e117–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diamond, I.R.; Grant, R.C.; Feldman, B.M.; Pencharz, P.B.; Ling, S.C.; Moore, A.M.; Wales, P.W. Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinman, A.; Benson, P. Anthropology in the clinic: The problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- American Psychiatric Association. Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI). Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwi10c2tkaf2AhWRS_EDHaWwBbQQFnoECDoQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.psychiatry.org%2FFile%2520Library%2FPsychiatrists%2FPractice%2FDSM%2FAPA_DSM5_Cultural-Formulation-Interview.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0yl4EMDbxmpSbT2uVcJfOL (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Schröer, H. Interkulturelle Öffnung und Diversity Management: Konturen einer neuen Diversitätspolitik der Sozialen Arbeit. In Soziale Arbeit in der Migrationsgesellschaft: Grundlagen-Konzepte-Handlungsfelder; Blank, B., Gögercin, S., Sauer, K.E., Schramkowski, B., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 773–785. ISBN 3658195398. [Google Scholar]

- Auernheimer, G. Diversity und interkulturelle Kompetenz. In Arbeitsfeld Interkulturalität: Grundlagen, Methoden und Praxisansätze der Sozialen Arbeit in der Zuwanderungsgesellschaft; Kunz, T., Puhl, R., Eds.; Juventa-Verl.: Weinheim, Basel, 2011; pp. 167–181. ISBN 9783779922087. [Google Scholar]

- Leenen, W.R.; Groß, A.; Grosch, H. Interkulturelle Kompetenz in der Sozialen Arbeit. In Interkulturelle Kompetenz und Pädagogische Professionalität, 4th ed.; Auernheimer, G., Ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; pp. 105–126. ISBN 9783531199306. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, S.; Horne, M.; Hills, R.; Kendall, E. Cultural competence in healthcare in the community: A concept analysis. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, 590–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brottman, M.R.; Char, D.M.; Hattori, R.A.; Heeb, R.; Taff, S.D. Toward Cultural Competency in Health Care: A Scoping Review of the Diversity and Inclusion Education Literature. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordijk, R.; Hendrickx, K.; Lanting, K.; MacFarlane, A.; Muntinga, M.; Suurmond, J. Defining a framework for medical teachers’ competencies to teach ethnic and cultural diversity: Results of a European Delphi study. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.R. Healthcare inequality, cross-cultural training, and bioethics: Principles and applications. Camb. Q. Healthc. Ethics 2008, 17, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, T.L.; Childress, J.F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 7th ed.; Oxford Univ. Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-19-992458-5. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Geneva: Adopted by the 2nd General Assembly of the World Medical Association, Geneva, Switzerland, September 1948; and amended by the 22nd World Medical Assembly, Sydney, Australia, August 1968; and the 35th World Medical Assembly, Venice, Italy, October 1983 and the 46th WMA General Assembly, Stockholm, Sweden, September 1994: And editorially revised by the 170th WMA Council Session, Divonne-les-Bains, France, May 2005; and the 173rd WMA Council Session, Divonne-les-Bains, France, May 2006; and amended by the 68th WMA General Assembly, Chicago, United States, October 2017. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-geneva/ (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Newham, R.; Hewison, A.; Graves, J.; Boyal, A. Human rights education in patient care: A literature review and critical discussion. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdman, J.N. Human rights education in patient care. Public Health Rev. 2017, 38, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, K.C.; Mishori, R.; Ferdowsian, H. Twelve tips for incorporating the study of human rights into medical education. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Physicians for Human Rights. Through Evidence, Change is Possible. Physicians for Human Rights. Available online: https://phr.org/ (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- IFHHRO. Medical Human Rights Network. Available online: https://www.ifhhro.org/ (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Pacquiao, D.F. Nursing care of vulnerable populations using a framework of cultural competence, social justice and human rights. Contemp. Nurse 2008, 28, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czollek, L.C.; Perko, G.; Weinbach, H. Social justice und diversity training. Arch. FÜR Wiss. Und Prax. Der Soz. Arb. 2012, 43, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czollek, L.C.; Perko, G.; Czollek, M.; Kaszner, C. Praxishandbuch Social Justice und Diversity: Theorien, Training, Methoden, Übungen, 2nd ed.; Juventa Verlag ein Imprint der Julius Beltz: Weinheim, Basel, 2019; ISBN 3779938456. [Google Scholar]

- Jirwe, M.; Gerrish, K.; Keeney, S.; Emami, A. Identifying the core components of cultural competence: Findings from a Delphi study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 2622–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shepherd, S.M.; Willis-Esqueda, C.; Newton, D.; Sivasubramaniam, D.; Paradies, Y. The challenge of cultural competence in the workplace: Perspectives of healthcare providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kitson, A.; Marshall, A.; Bassett, K.; Zeitz, K. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, N.; Bower, P. Patient-centredness: A conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc. Sci. Med. An. Int. J. 2000, 51, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpaka, A.; Mecheril, P. “Interkulturell”: Von spezifisch kulturalistischen Ansätzen zu allgemein reflexiven Perspektiven. In Migrationspädagogik; Mecheril, P., Castro Varela, M.d.M., Dirim, İ., Kalpaka, A., Melter, C., Eds.; Beltz Verlag: Weinheim, Basel, 2010; pp. 77–98. ISBN 9783407342058. [Google Scholar]

- Zanting, A.; Meershoek, A.; Frambach, J.M.; Krumeich, A. The ‘exotic other’ in medical curricula: Rethinking cultural diversity in course manuals. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phillips, A. What’s wrong with Essentialism? Distinktion J. Soc. Theory 2010, 11, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanchez, J.I.; Medkik, N. The Effects of Diversity Awareness Training on Differential Treatment. Group Organ. Manag. 2004, 29, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiba-O’sullivan, S. The Distinction between Stable and Dynamic Cross-cultural Competencies: Implications for Expatriate Trainability. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 709–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirts, R.G. BAFA BAFA: A Cross-Cultural Simulation; Intercultural Press: Del Mar, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Thiagarajan, S. Barnga: A Simulation Game on Cultural Clashes, 25th ed.; revised and enhanced, [repr.]; Intercultural Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 9781931930307. [Google Scholar]

- Gudykunst, W.B.; Guzley, R.M.; Hammer, M.R. Designing Intercultural Training. In Handbook of Intercultural Training: Issues in Theory and Design; Landis, D., Brislin, R.W., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Burlington, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 61–80. ISBN 9780080275338. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, M.Y.; Kriegel, M.; Aylett, R.; Enz, S.; Vannini, N.; Hall, L.; Rizzo, P.; Leichtenstern, K. Technology-Enhanced Role-Play for Intercultural Learning Contexts. In Entertainment Computing–ICEC 2009; Natkin, S., Dupire, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 73–84. ISBN 978-3-642-04052-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bhawuk, D.; Brislin, R. Cross-cultural Training: A Review. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 49, 162–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, M. Engaging With Issues of Cultural Diversity and Discrimination Through Critical Emotional Reflexivity in Online Learning. Adult Educ. Q. 2008, 59, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novy, I. Interkulturelle Kompetenz–zu viel Theorie? Erwägen Wissen Ethik 2003, 14, 206–207. [Google Scholar]

- Linck, G. Auf Katzenpfoten Gehen und das qi Miteinander Tauschen-Überlegungen Einer China-Wissenschaftlerin Zur Transkulturellen Kommunikation und Kompetenz. Erwägen Wissen Ethik 2003, 14, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brach, C.; Fraser, I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2000, 57 (Suppl. S1), 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinder, R.J.; Ferguson, J.; Møller, H. Minority ethnicity patient satisfaction and experience: Results of the National Cancer Patient Experience Survey in England. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kambale Mastaki, J. Migrant patients’ satisfaction with health care services: A comprehensive review. Ital. J. Public Health 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Kantamaturapoj, K.; Putthasri, W.; Prakongsai, P. Challenges in the provision of healthcare services for migrants: A systematic review through providers’ lens. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robertshaw, L.; Dhesi, S.; Jones, L.L. Challenges and facilitators for health professionals providing primary healthcare for refugees and asylum seekers in high-income countries: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brandenberger, J.; Tylleskär, T.; Sontag, K.; Peterhans, B.; Ritz, N. A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries-the 3C model. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortin, S.; Maynard, S. Diversity, Conflict, and Recognition in Hospital Medical Practice. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2018, 42, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mecheril, P. Natio-kulturelle Mitgliedschaft-ein Begriff und die Methode seiner Generierung. Tertium Comp. 2002, 8, 104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bolten, J. Fuzzy Cultures: Konsequenzen eines offenen und mehrwertigen Kulturbegriffs für Konzeptualisierungen interkultureller Personalentwicklungsmaßnahmen. Mondial. Sietar J. FÜR Interkult. Perspekt. 2013, 19, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Welsch, W. Transkulturalität: Realität und Aufgabe. In Migration, Diversität und Kulturelle Identitäten: Sozial-und Kulturwissenschaftliche Perspektiven; Giessen, H.W., Rink, C., Eds.; J.B. Metzler: Stuttgart, Germany, 2020; pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-3-476-04372-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, E.; Verdooren, A. Diversity Competence: Cultures Don’t Meet, People Do; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 2019; ISBN 9781789242409. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, E.; Kätker, S. Diversity Management: Organisationale Vielfalt im Pflege-und Gesundheitsbereich Erkennen und Nutzen, 1. Aufl.; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2007; ISBN 3-456-84419-0. [Google Scholar]

- Van Keuk, E.; Giesler, W. Diversity Training im Gesundheits-und Sozialwesen am Beispiel des EQUAL Projektes. In Interkulturelle Kompetenz im Wandel: Ausbildung, Training und Beratung; Otten, M., Scheitza, A., Cnyrim, A., Eds.; IKO: Frankfurt, Germany, 2007; pp. 147–173. ISBN 9783889399007. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; ISBN 9789241563703. [Google Scholar]