Abstract

During COVID-19, emergency measures, such as physical distancing and program restrictions, have reduced community-based supports for PLWD and their caregivers. Consequently, reductions in dementia services and resources have contributed to existing health inequities in this population. Academic databases were searched in July 2020. Grey literature was retrieved using the CADTH Grey Matters tool. Articles from 2000 to 2020 in English and from high-income countries were included. Literature that discussed any changes to community support and services for PLWD and/or their caregivers during any infectious respiratory outbreak was included. Findings were extracted using a template adapted from the Health Equity Impact Assessment (HEIA) tool. A total of 15 articles were identified; all focused on the COVID-19 pandemic. Evidence was primarily based on expert opinion, with only three primary research studies meeting inclusion criteria. Most alterations to dementia services described switching to telehealth platforms. There was limited information on social determinants of health and how these intersected to influence the experience of service changes among different populations. More research is needed to better understand how services for PLWD can continue or be transitioned online during infectious disease outbreaks and address issues of health (in)equities for PLWD and/or their caregivers.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic on 11 March 2020 [1]; public health emergency measures were widespread and significantly impacted health and social service delivery, access and experience. Physical distancing involves sheltering in place where possible, limiting contact and maintaining a distance from other people who do not live in your household, as well as staying home if you are diagnosed with, or are suspected of having, COVID-19 [2]. The effects of these measures had a particularly negative impact on people who were identified as being at greater risk for severe outcomes related to COVID-19, such as older adults and those with pre-existing health conditions [3]. Understanding the initial reaction to the pandemic among community services and supports is important to support planning for future pandemics and for examining how equity is addressed at the outset in emergency management. This review explores how community services, supports and resources for PLWD and their caregivers were affected during the first wave of COVID-19 and how equity was addressed in these changes.

Persons living with dementia (PLWD) often need health and social supports to live in the community and there is concern that they are disproportionately affected by emergency health measures and restrictions during infectious disease outbreaks. During COVID-19, public health emergency measures that required PLWD to remain at home exacerbated loneliness and anxiety [4]. This was further intensified by service changes, such as reductions in home care, lack of social outings and, for many people, inability to access digital and communications technologies, such as smartphones or tablets, to connect with loved ones [4,5,6].

The review was designed in the Spring of 2020, and the search completed in July 2020. While we were open to literature reporting on any infectious outbreak, we only identified relevant literature related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The review captured an important timeframe in the COVID-19 pandemic trajectory—what has been identified as its first wave [7]—in which there was great uncertainty around viral transmission, rates of infection and outcomes of the disease and no vaccine was available, which triggered severe limitations on contact between people.

1.1. Dementia

Dementia is a condition involving changes in memory, cognition and behaviour that can significantly impact individuals’ abilities to care for themselves [8]. Dementia is estimated to affect 50 million people worldwide and is expected to triple in prevalence by 2050 [9]. There is no cure or intervention that is effective in halting the progression of the condition; therefore, efforts to promote quality of life (QOL) and living well with dementia are central to dementia care. Most PLWD reside in the community outside long-term care homes and continue to live at home in the community with the support of family and friend caregivers [10].

Meeting the health and social needs of PLWD is often complex. PLWD are not only at a greater risk of social isolation and loneliness [11] but also additional comorbidities, including heart failure, diabetes or chronic lung disease [12]. These individuals may require significant assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) and may demonstrate signs of depression or exhibit responsive behaviours [10]. Responsive behaviours demonstrated by PLWD include agitation, wandering or speaking out in response to negative, overwhelming or frustrating circumstances [13]. While caregivers are instrumental in caring for PLWD, high levels of stress and depression have been reported among caregivers of PLWD. This stress increases with disease progression, time spent caring for a loved one, increased dependency to perform ADLs and demonstration of responsive behaviours by a PLWD [14]. Therefore, a broad range of resources and supports in the community are needed to promote the wellbeing of PLWD and their caregivers, provide essential care and offer opportunities for social interactions.

1.2. Community Services, Supports and Resources

National and global dementia advocacy organizations identify the need for high-quality, accessible community services, supports and resources for PLWD and their caregivers to promote well-being, address health concerns and enable independent living in the community for as long as possible [15]. There are a range of community-delivered supports and services and resources to support PLWD living in the community; these supports vary across jurisdictions. Many areas have home care services that provide nursing care, personal supports and/or help with light household tasks, such as meal preparation, cleaning and laundry. Other community-based services include respite care, in-home companionship, adult day programs, transportation, housekeeping, grocery or prescription pickup, as well as support programs for PLWD and their caregivers, caregiver training or education and brain health activities [16].

1.3. Public Health Emergency Measures

This review was conducted in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in which governments across the globe placed significant restrictions on social movements and interactions. During COVID-19, access to community supports, services and resources were altered due to the high risk of transmitting an infection between people through close contact. Emergency public health measures were enacted to reduce the risk of spreading the infection, such as restrictions on social contact. For PLWD living in the community, efforts to reduce COVID-19 viral transmission during wave 1 likely impacted the ability to access crucial in-person supports, services and resources due to increased demand, delays or unavailability of these services [17]. Additionally, physical distancing may have presented unique challenges for PLWD who live in the community. For people who required supports to meet their daily needs, it was not realistic to completely limit social contacts [10]. Isolation measures can disrupt routines that are important for promoting health among PLWD, which can lead to poor sleep, lowered physical activity and decreased social engagement [18]. Moreover, PLWD and their caregivers may have also experienced anxiety due to a heightened risk of serious illness resulting from COVID-19 [18]. As such, it has been suggested that the changes in health services and availability of community resources during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated existing health inequities for PLWD [18].

1.4. Health Equity

People living with dementia experience health inequities due to stigma and barriers to healthcare. Health inequities are “differences in health outcomes that are avoidable, unfair and systemically related to social inequality and marginalization” [19]. Stigma related to dementia is common in healthcare settings and it has been associated with unmet needs among this population and with long-term health consequences, including negative mental health effects and depression [12,20]. Among those living with dementia, members of LGBTQ2S+ communities, people with disabilities and diverse ethnocultural populations experience health disparities related to systemic discrimination, a lack of culturally safe and appropriate person-centered services and barriers to diagnosis of dementia [12,21,22]. Other factors, such as remote geographic residence, and economic factors also create barriers to accessing dementia-related services, supports and resources [23,24,25].

There is potential for public health emergencies to have unique and significant effects on people with chronic health conditions, such as dementia. Editorial articles aimed at describing the effects of COVID-19 on older adults suggest that it is important to increase awareness of maintaining social connectedness and involve older adults in decisions regarding basic care services during emergency procedures to promote dignity and autonomy [26]. However, there remains a need to understand the impact of COVID-19 on service delivery to help inform future efforts to track, analyze, interpret and address issues of health (in)equities for PLWD and their caregivers under future public health emergency measures.

Given the potentially serious and differential impacts of physical and social distancing during infectious outbreaks on PLWD, it is important to examine the changes to community resources, supports and services for the broad spectrum of people who rely on them to continue to live in the community. This rapid scoping review, therefore, aimed to assess evidence that described how resources, supports and services changed during infectious disease outbreaks in high-income countries and how issues of equity were addressed in those changes.

A preliminary search of PROSPERO, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and JBI Evidence Synthesis was conducted in July 2020. No current or in-progress scoping reviews or systematic reviews exploring changes to community-based supports and resources for individuals with dementia and their caregivers during COVID-19 or other infectious respiratory disease outbreaks were identified.

Other reviews on issues related to COVID-19 that concern the aging population are in progress and may provide insight into this population. These reviews include topics on the impacts of acute respiratory disease epidemics, including COVID-19, on older adults’ mental health [27,28] and the relationship between frailty and mortality among patients with COVID-19 [29]. Additionally, scoping reviews examining the role of social inequities in COVID-19 and the mental health implications of infectious disease epidemics on informal carers of affected individuals and relatives are currently in progress [30]. In summary, there are no current reviews in progress or published that examine the community supports and resources available to PLWD and their caregivers during infectious respiratory disease outbreaks.

A scoping review is an appropriate method to explore this emerging body of literature in the dynamic context of COVID-19. This review will describe how services for PLWD and caregivers have been impacted during public health emergency restrictions and support recognition of and attendance to the structural determinants and health inequities that shape how PLWD and caregivers access supports during public health emergencies. The synthesis of current types and quantities of literature, as well as explorations of themes and gaps in the literature, will help to inform further research and potential reviews [31].

2. Materials and Methods

The scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews [31]. We also followed the PRISMA extension for equity-focused systematic reviews [32]. The search strategy was developed with the support of a library scientist (MR) trained in JBI methodology and located published and unpublished articles. This scoping review was registered with the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools, which can be accessed at https://www.nccmt.ca/covid-19/covid-19-evidence-reviews/139, (accessed on 25 July 2020).

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

This review considered articles that included any PLWD in the community and/or their caregivers. PLWD and caregivers could be of any age. Caregivers include family members, friends or others identified in the article as providing care to the PLWD, whether they are living or not living in the same household. Articles that focused on individuals living in long-term residential care or assisted-living facilities were excluded.

Articles that explored dementia-related community services, supports and resources, including home care, were included. We considered how service changes intensified or intersected with issues of equity, namely, unfair differences in service provision based on characteristics such as income, sex/gender, disability, geography and ethnicity [32].

This scoping review considered original research and text and opinion papers. Quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods study designs, systematic reviews and grey literature were considered. Blogs, newspaper articles, policy papers and websites sharing information but not reporting on changes to community services, supports and resources were excluded.

Only articles published in the English language were included due to the limited resources of the study team and the rapid nature of the review. The search was initially limited to sources published since 2000 to identify literature related to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreaks [33]. Ultimately, only articles published from the onset of the COIVD-19 pandemic to the peak of the first wave (June 2020) were included. This enabled us to examine the initial reaction to the pandemic and how equity was considered in this reactionary phase.

2.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy aimed to locate both published and unpublished primary studies, reviews and grey literature from high-income countries. The start date of the literature examined went as far back as 2000 to capture articles on pandemic responses related to COVID-19 and other infectious outbreaks [33]. A three-step search strategy was used to identify published literature. An initial limited search of MEDLINE and CINAHL was undertaken followed by an analysis of index terms contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles, and the index terms used to describe the articles were used to develop a full search strategy. A second systematic search using all identified keywords and index terms was adapted for each included information article and a second search was undertaken on 2 July 2020. Third, the reference lists of all identified full text articles was searched for relevant articles. The full search strategies are provided in Appendix A.

The databases that were used to search for published literature were CINAHL (Ebsco), Medline (Ovid) and Embase (Elsevier). The grey literature search was completed by August 2020. We used the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH) checklist [34] to identify relevant websites and digital repositories, such as various government websites and jurisdictional chapters of the Alzheimer’s Society (see Appendix B for list of included articles). These articles were searched using the major search terms, including “dementia” and “COVID-19”. High-income countries were identified using criteria from the World Bank [35], and Advanced Google searches were limited to these specific countries. The results of the Advanced Google searches were reviewed five pages past the last relevant article.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

Following the search, all identified records were collated and uploaded into Covidence systematic review software (Vertitas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) and duplicates were removed. Following a pilot test, titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers for assessment against the inclusion criteria for the review. Titles and abstracts were reviewed by two reviewers independently according to predetermined selection criteria. Next, articles selected from the title and abstract phase were screened for full-text inclusion by two independent reviewers. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or with a third reviewer.

Data extraction was conducted by two independent reviewers using a data extraction tool adapted from the Health Equity Impact Assessment (HEIA) tool [19]. The extracted data included specific details about the population, concept, context, study methods and key findings relevant to the review objective. A draft charting table is provided (Appendix C). Social determinants and their intersections were considered in provision of care across populations. Any mention of social determinants of health, directly or indirectly, when describing informal or formal care services or suggestions for changes to services during infectious disease outbreaks were extracted using the HEIA tool.

Extraction grid findings from the two reviewers were amalgamated and any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or by a third reviewer.

The results are reported with a summary table and narrative text under four headings: essential services and caregiving, telehealth, other resources and supports and health equity considerations within the literature (Table 1).

3. Results

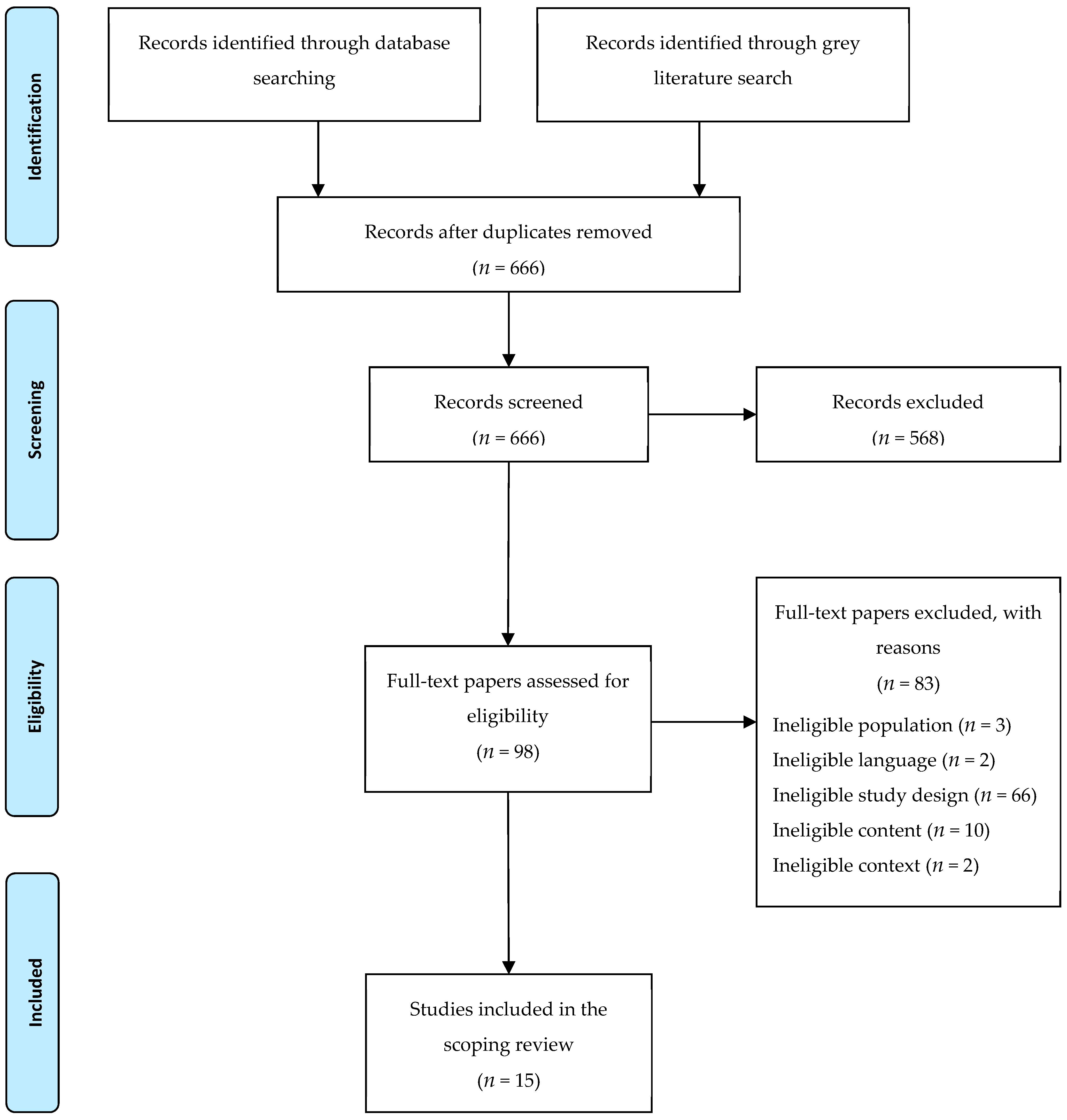

There were 794 articles retrieved from the database and grey literature searches. Of these, 128 were removed as duplicates. A total of 666 articles were screened during the title and abstract phase with 568 excluded. Following this, 98 articles were screened at the full text phase and 83 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion at the full text screening phase included: grey literature that did not report on new services or supports (n = 66), articles focused on non-dementia-specific resources and services (n = 10), articles that did not discuss PLWD or caregivers specifically (n = 3), articles that were not written in English (n = 2) and articles that did not include PLWD residing in the community (n = 2) (Figure 1, PRISMA diagram). Fifteen articles were eligible for data extraction. No relevant articles were identified from extracted study reference lists.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of included and excluded articles for scoping review.

3.1. Characteristics of Included Articles

In Table 1, the characteristics of the included articles are presented. Articles included editorials or commentary articles (n = 5) [36,37,38,39,40], letters (n = 2) [41,42], research studies and/or letters (n = 4) [43,44,45,46], a research protocol (n = 1) [47], a report (n = 1) [48] and literature reviews (n = 2) [18,49]. Among the articles, the two research letters described a single person’s account of their experience under COVID-19 pandemic emergency measures and how they experienced reductions in health services [43,46]. The other research studies included a telephone survey assessing the impact of a television-delivered telehealth intervention [44] and a telephone interview to explore experiences using telehealth-delivered neuroscience clinic services [45], along with two articles commenting on the experiences of PLWD and their caregivers during COVID-19 [36,41]. The literature was from Italy (n = 2) [36,43], Hong Kong (n = 1) [41], Canada (n = 2) [18,45], Ireland (n = 2) [42,46] the UK (n = 2) [46,48], Australia (n = 1) [40], Spain (n = 2) [44,47] and New Zealand (n = 1) [39] or did not discuss a specific country (n = 2) [37,38].

Table 1.

Summary table of identified articles.

Table 1.

Summary table of identified articles.

| Authors and Date | Country | Article Type | Aim | Population | Services, Resources | Equity Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al. (2020) [18] | Canada | Perspective review of literature | Propose mitigation strategies for issues within the context of the evolving COVID-19 situation and future dementia care | People with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, their caregivers and clinicians | Essential Services and Caregiving: Reliance on public transit increases risk of infection, meals on wheels. Disrupted pharmacy services. Home healthcare reduced, increased demand and unavailability due to exposure risk. Caregiver anxiety and risk of spreading illness, inadequate PPE; Telehealth: Virtual diagnosis via videoconferencing deferred, some follow-up appointments can be made online. Telecommunication challenges due to cognitive impairment (need instructions and supports to use tools) | Adequate housing options for persons with ADRD. PWD likely suffer disproportionally from reduced availability of resources and stigmatization |

| Canevelli et al. (2020a) [43] | Italy | Research letter | Reports on a study explore how clinical conditions and cognitive disturbances in PWD have changed during the pandemic to plan for care during the post emergency phase | People with dementia who attended the Center for Cognitive Disturbances and Dementia (n = 139) | Essential Services and Caregiving: Services and facilities suspended or reduced, need for re-opening soon as possible to serve high demand. Suggest educational materials for caregivers; Telehealth: Suggest telehealth | |

| Canevelli et al. (2020b) [36] | Italy | Editorial | Implications of transitioning from crisis care to ongoing care for people with dementia | Persons living with dementia and their caregivers | Essential Services and Caregiving: Food delivery, supermarket bookings, medication deliveries. Daily routine development; Telehealth: use for post-pandemic services to reduce long wait times in hospitals, electronic diaries to monitor symptoms, smartphone tablets to keep in touch/cognitive stimulation | |

| Cheung and Peri (2020) [39] | New Zealand | Editorial | virtual Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (vCST) as a case example of how technology used to deliver a group intervention for people with dementia during COVID-19 | PLWD and caregivers | Telehealth: Zoom for facilitators to collaborate and form “Community of Practice”. virtual Cognitive Stimulation Therapy for people with dementia program transitioned online during COVID-19 | Ethnoracial: New migrants with dementia can also access a vCST programme in their home country; Rural/Remote: available to people who live in rural areas where there is no in-person CST programme in close proximity, transportation; Disability: online services accessible for persons with impaired mobility |

| Cuffaro et al. (2020) [37] | Italy (global perspectice) | Commentary | Suggests different technologies to be implemented during COVID-19 to provide care for PWD during pandemic | PLWD requiring clinical services and caregivers | Essential Services and Caregiving: Reduced clinical services; Telehealth: Remote delivery of clinical follow ups, referrals, videoconferencing to reduce waiting lists post-pandemic) | Challenges to using technology by older demographic mentioned |

| Devita et al. (2020) [38] | N/A | Commentary | Summarize cognitive impacts as a result of public health measures and current research on remote interventions | Frail individuals with neurocognitive disorders and caregivers | Essential Services and Caregiving: Information for caregivers delivered online; Telehealth: virtual assessments and need for standardizing virtual assessment tools; suggest cognitive stimulation training | Lack of data published on COVID-19 that implicates subpopulation of frail individuals with neurocognitive disorders |

| Goodman-Casanova et al. (2020) [44] | Spain | Research—survey | Assess wellbeing during social distancing and the impact of telephone and television-based intervention with TV-AssistDem on physical and mental health | Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Mild Dementia (n = 93) | Essential Services and Caregiving: 73% had medications and groceries delivered by family member (73%). Activities continued to be carried out on own included walking, memory games, watching TV, phoning family and friends; Telehealth: No significant differences in health and well-being between groups, however, respondents with TV-AssistDem performed more memory exercises | Sociodemographic and health information of sample presented: 63% female; avg age of 73; 74% lived accompanied; 18% altered living arrangements during COVID-19 |

| Lloyd-Williams et al. (2020) [49] | UK | Rapid review | Gather evidence for non-technology- based activities that can be delivered at home by family carers, to maintain cognitive function in people with dementia who are socially isolating during COVID-19 | PLWD and caregivers | Essential Services and Caregiving: Suggest caregiver-delivered reminiscence therapy; cognitive stimulation therapy; music-based interventions; art therapy; meaningful activity (e.g., recreational activities and social time, puzzles) | N/A |

| Mayoral-Cleries, Fermin (2020) [47] | Spain | Research Protocol | Multicentre cohort study aims to explore and analyze impact of social isolation on cognition, quality of life, mood, technophilila stress; health and social care services access and utilization; and cognitive, social and entertainment use of ICTs | Community-dwelling older adults with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia and their caregivers (n = 152) | Essential Services and Caregiving: Community-based healthcare and social support services access use; Telehealth: Information and communications technology use during isolation | |

| O’Shea (2020) [42] | Ireland | Letter to the editor | Describes need for increased attention to people with dementia during COVID-19 pandemic for person-centred care and support | Older adults (aged 70+) with dementia living with/without caregiver | Essential Services and Caregiving: Suggest shopping and medicine supply support; Telehealth: Suggest phone calls and social media as means of communication to promote empathy | |

| National Health Service (2020) [48] | UK | Regional Health System Support | Describe how alterations to NHS services were impacted during COVID-19 and how to transition to return to service in future a region | People with dementia | Telehealth: Shift of clinical assessments online, lack of diagnostic precision for medications, reduced memory service referrals; identify need for virtual education and CST | |

| Pachana (2020) [40] | Australia | Commentary | Describes the national “Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19)” in Australia and the impact on older adults’ access to services, people living with dementia and mental health conditions and indigenous communities | General public, people living with dementia and their families, indigenous communities | Essential Services and Caregiving: Evacuation and travel insurance; Formal Home care: Reduced consultations and services. Lack of contact with family members for care/socialization; Telehealth: Online supports for older people, Internet-based mental health services health specialists.; user challenge | Disproportionate impact on disadvantaged people and communities, stigma and ageism during pandemic |

| Roach et al. (2020) [45] | Canada | Research—Interview | Creation of evidence base for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on well-being and healthcare of persons living with dementia | PLWD and family members/care partners who had attended the Cognitive Neurosciences Clinic (n = 21) | Essential Services and Caregiving: Reduced personal support/homecare, increased caregiver responsibility; Telehealth: Remote delivery of care; options for video or telephone call | Homogeneous urban sample |

| Rochford-Brennan and Keogh (2020) [46] | Ireland | Research—Letter | Provide personal account of a person with dementia of living through this pandemic | One PLWD | Essential Services and Caregiving: Person was a caregiver for her spouse. Suggested a simple sheet of resources be given to community-dwelling persons with dementia; Telehealth: Helplines, “Community Call” initiative | Location in West Ireland, lack of technology infrastructure, cannot access online supports during COVID-19 |

| Shea (2020) [41] | China | Letter | Outlines effects of the pandemic on persons living with dementia or cognitive impairment, irrespective of living situation | PLWD or cognitive impairment and their caregivers. | Essential Services and Caregiving: Meal delivery service, home care, urinary catheter care and wound. PPE need for informal caregivers; physical exercise care; medication management; Telehealth: Telecommunication offered to support connection between clients and caregivers (social and emotional support), advanced care directives through telehealth |

3.2. Nature of Changes to Services, Supports and Resources

The included articles identified services, supports and resources that addressed a variety of issues, including physical health of PLWD [36,38,44,45,48], such as telehealth programs or an off-hours telephone support line [48]. Three articles mentioned mental health and the use of CST, a psychosocial and cognitive intervention that has been shown to improve communication, quality of life and cognition [38,39,48]. Two articles reported programs that supported access to essential services for PLWD, including groceries and medication [36,45]. One article discussed social isolation and the use of phone calls to people with dementia during the pandemic [45] and another described the provision of educational material about the pandemic through a technology intervention that was already being evaluated [44].

3.3. Essential Services

Articles outlined multiple types of essential services that were disrupted and/or faced an increase in demand during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. These alterations to services meant that caregivers had a greater need for PPE and other medical supplies [50], respite services were canceled, [40] medication delivery and pick-up services were used more often, [18,35] public transportation was used more frequently [18], PWLD and caregivers used supermarket bookings and food delivery more often [36]. Home care services were also reduced during COVID-19 due to physical distancing restrictions; efforts were made to limit the number of care providers entering the home of PLWD and reduce the risk of exposure to COVID-19 between caregivers and paid care providers [18]. Shea et al. (2020) discussed the importance of maintaining existing programs that provided essential services; they described a program called Integrated Care and Discharge Support that was implemented to provide meal deliveries, wound and catheter care, physical activity and medication management while COVID-19 restrictions remained in place [41].

3.4. Telehealth

Most articles (n = 9) discussed telehealth for healthcare service delivery or the use of smartphones and telephones to increase socialization of PLWD [18,37,38,39,40,44,45,46,48]. The use of videoconferencing was suggested in multiple articles to deliver interventions. including CST [38,39] and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) [40]. Other uses of telemedicine included a television-based program that delivered education on physical activity exercises and provided a platform for video-calling and memory games during physical isolation [44]. Telephone lines to communicate information and provide support for caregivers and PLWD were also mentioned in commentary articles as important for persons experiencing social isolation [46,50]. Canevelli et al. (2020) suggested that physicians and nurses periodically contacting PLWD and caregivers to provide educational information can help maintain connection with care providers and manage caregiver stress experienced during COVID-19 [36]. An example of this was also mentioned by Rochford-Brennan and Keogh (2020) who proposed a telephone support initiative called “community call”, although this initiative was not offered to PLWD specifically [46]. Although not the focus of this scoping review, several articles described the use of telehealth for the purpose of clinical dementia assessment and diagnosis [37,38,48] and delivery of specialized clinical services previously provided in person [45].

The use of virtual CST (vCST) was proposed as a way of enhancing social connectedness among those who live in rural areas to eliminate the need for transportation to treatment centres. In a study by Cheung and Peri (2020), the training and planning of CST sessions that were transitioned from in person to online using a “community of practice” enabled facilitators to collaborate to design and share vCST interventions via the cloud-based virtual communications application Zoom (Zoom Video Communications Inc, California, USA). Of those who were able to receive online services, PLWD enjoyed the ability to reconnect with others and facilitators reported that the program was feasible. Additionally, the ability to offer vCST in various languages can connect diverse PLWD with facilitators globally [39]. Participants who received specialist neuroscience clinical services remotely noted benefits that included increased time to interact with physicians via virtual platforms, having the option for telephone only and the ability of caregivers to ask more questions [45]. Other services that shifted to remote platforms, such as social worker consultations with PLWD and their caregivers, were thought to promote continuation in care and familiarity during pandemic emergency measures [50].

Furthermore, the use of electronic reminders, daily activities, cognitive stimulation games, text messaging, chat forums and web-based training for caregivers were proposed as options to reduce caregiver burden and increase socialization among PLWD. Using data from a multicentre randomized controlled trial, Goodman-Casanova et al. (2020) [44] examined the impact of a television-based intervention (TV-AssistDem) for PLWD or mild cognitive impairment. This television system included a service box and webcam to enable video calling between PLWD and others, including healthcare professionals, watching videos with public health information and COVID-19, watching videos of physical activity exercises at home and participating in various memory games. The authors found that PLWD engaged in more memory exercises than the control group. Although there were no other significant differences between groups, the authors suggest that the TV-AssistDem services can help promote activity, cognitive stimulation and socialization to prevent cognitive decline in PLWD [44].

While telehealth platforms enabled the continuation of services and support during COVID-19 for PLWD and caregivers, several authors noted challenges with telehealth due to Internet accessibility and digital literacy [38,39,45,46]. These challenges were documented in the personal account of a rural-dwelling PLWD in Ireland [46] and in interviews conducted by Cheung and Peri (2020). Analysis of these interviews revealed that only half of the PLWD who initially attended in-person CST sessions were able to transition to an online platform due to challenges with Internet or device access or the availability of a caregiver to assist them [39]. Some participants required additional technology support, such as one-on-one pre-training with the technology, and assistance with set-up by caregivers. Furthermore, even with the ability to access telehealth to continue clinical services in-home during COVID-19, PLWD and their caregivers revealed that there were concerns over interpreting body language and privacy and information sharing between caregivers and clinicians when caregivers were present during online Zoom meetings. As such, Pachana et al. (2020) state that while CBT can help reduce anxiety and depression among PLWD during isolation, conducting remote interventions and assessments with PLWD creates challenges even when caregivers are present for support [40].

3.5. Other

Among other resources and services that were identified within the included articles, Lloyd-Williams et al. (2020) summarized current evidence for non-technology-based activities to be delivered at home for PLWD. Among these activities, reminiscence therapy using items around the home, CST, music-based interventions, art therapy and other meaningful activities, such as puzzles and reading, for PLWD who were isolating was suggested to help reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms and improve QOL and relationships for PLWD and caregivers. However, more research is needed to explore how caregivers can best provide these various types of therapies [49]. Alternatively, among technology-based interventions, Devita et al. proposed educational online sessions for caregivers of PLWD to navigate cognitive, behavioural and affective changes and clinical advice from professionals [38]. Similarly, O’Shea (2020) described a weekly educational TV program that would broadcast informative content on physical activity, sensory stimulation activities and other home activities [42].

3.6. Health (In)Equity

Guided by the HEIA tool, we found that few articles considered the social and structural determinants of health, existing or potential health and social care disparities experienced by specific populations or the intersection of different social categories, such as age, race, ethnicity, gender and sexual identity, disability or the structures and relations of power that underpin them, in the context of dementia care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Below we will discuss the four articles that contained findings related to equity issues, which highlighted the promise of virtual technology in maintaining social connection across geographic boundaries for immigrant populations, dementia-appropriate approaches to sheltering for PLWD to prevent or treat COVID-19 and the discrimination and treatment disparities resulting from ageism that may be perpetuated by COVID-19 responses emphasizing vulnerability.

A case study by Cheung and Peri (2020) suggested that vCST platforms can connect rural-dwelling individuals with limited transportation options, connecting linguistically diverse PLWD with moderators and new migrants with others from their home country. They suggest the globalization of CST could improve accessibility of CST amongst developed and developing countries to benefit PLWD across a range of geographic locations [39].

As part of the survey conducted by Goodman-Casanova et al. (2020), the authors found that nearly 20% of PLWD in Spain experienced an altered family housing situation during the COVID-19 emergency restrictions [44]. The prospective review by Brown et al. (2020) also recognized that housing was a potential issue for PLWD during COVID-19 emergency measures going forward. The authors described the potential for PLWD to be discharged from hospital, evacuated or diverted to temporary accommodations (e.g., hotels, temporary treatment centres), where they may not receive dementia-related supports and services. Consequently, this precarious housing situation may lead to increased frailty and morbidity among PLWD [18].

Stigmatization of older adults and PLWD during the COVID-19 crisis and the real and perceived effects on health outcomes were discussed in multiple articles. Ageism and societal assumptions about the increased frailty and vulnerability of older adults and PLWD during COVID-19 may contribute to isolation and segregation, with a higher likelihood of emotional and physical impacts on the wellbeing of these populations. Physical distancing and social isolation of PLWD and caregivers who were experiencing social distancing prior to the pandemic further limited and obstructed opportunities to connect and participate in the kind of collective solidarity needed to respond to the adversities associated with the COVID-19 crisis [40]. Additionally, Pachana et al. (2020) reported that families feared the discrimination of PLWD in critical care settings due to triaging by age or presence of cognitive impairment and the limited availability of PPE and medical supplies. Brown et al. (2020) further noted concerns related to the allocation of resources and discussed how to ethically approach triaging PLWD in situations of limited resources as the COVID-19 pandemic progresses [19].

4. Discussion

This review provided a unique opportunity to explore the initial reaction to a global pandemic in terms of services, supports and resources for PLWD and how those reactions affected equity among PLWD. The review includes articles from the peak of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic and thus identifies what was documented when the pandemic and associated emergency public health measures were first initiated. It bears witness to the kind of information circulating in the early days of the pandemic, and to the nature of the response from research communities, The literature collected in this review was generally limited to anecdotal evidence that commented on reduced services and resources, the emergence of telehealth in lieu of in-person services and supports and provided some discussion of the potential future impacts of reduced home care and essential services during COVID-19 for PLWD and their caregivers. This reflects the published body of literature accessible to policymakers and health system leaders toward the end of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Health equity was not well accounted for within the included articles. In materials published during the first wave of the pandemic, PLWD were being considered as a singular, homogenous group, as were their caregivers. Differences in care needs and situations tended to be represented as a consequence of the type or severity of dementia rather than geographic, social or cultural location. During a public health crisis, a lack of attention to differences in access to and experiences of support within and among PLWD and caregiver populations increases the vulnerability of individuals and groups who may already face barriers to health and wellness. This gap in knowledge published at the outset of COVID-19 is surprising, considering well-established pre-pandemic knowledge of health inequities for LGBTQ2S+, racialized and disabled persons resulting from historical and systemic discrimination and a general failure by formal service providers to recognize their unique experiences and the specific challenges they may face in accessing supports [51,52,53,54,55,56].

The intersection of age and other social determinants of health has created unintended impacts on PLWD and caregivers during COVID-19 emergency measures. While the full extent of the impact of public health emergency measures on dementia services for community-dwelling PLWD remains largely unknown, it is likely that these measures have exacerbated the already limited supports available to this population [46]. In a recent letter to the editor, Lee (2020) listed recommendations to better support vulnerable older adults living in the US during COVID-19, including PLWD. These included the increased use of social workers to provide support for those living in the community and advocacy for short-term and long-term supports, such as established protocols for home healthcare workers to both reduce COVID-19 transmission and maintain physical assistance for older persons living in the community, increased financial supports for caregivers and raising public awareness of older adults’ increased needs during COVID-19 [55]. Our review was limited to the initial four months of the COVID-19 pandemic after COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic in March 2020 and its trajectory was unknown. Public health guidance will continue to evolve as the pandemic progresses, which will determine how community services and resources support and impact PLWD and their caregivers living in the community and whether equity is more fully addressed.

The use of technologies, such as smartphones and tablets, was suggested as a way to promote socialization and memory and/or cognitive function. Many telehealth approaches were non-specific to emergency health measures and PLWD, yet they were the only option to create social outlets and continue certain services that were previously delivered in clinical settings pre-COVID-19. In a research study by Lai and colleagues (2020), the authors found that videoconferencing may prevent some decline in cognition and quality of life among PLWD and promote mental and physical health and self-efficacy among caregivers compared to phone telehealth only. They suggest this could be due to the increased social connection that videoconferencing provides [50]. However, most commentary articles included in this review focused on risk reduction and suggested that tools and assessment processes were not designed to be conducted through telehealth channels.

Telehealth approaches may be especially difficult for PLWD in comparison to those services delivered in person. Changes to services as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic are thought to create disruptions in care and routines that may promote anxiety and irritability among PLWD [57] and which may be exacerbated further if home care services and socialization opportunities are limited [6]. Furthermore, older adults and PLWD may be particularly vulnerable to digital exclusion, that is, the disenfranchisement and disadvantage that results from lesser access to digital technologies and the Internet [58,59,60]. Digital exclusion may be a particular consideration for older adults who often possess lower levels of computer literacy [58,59,60]. There are costs associated with accessing technology that may further impact their accessibility. The costs of the technologies themselves, such as smart phones, as well as many of the platforms and software (such as Zoom or Skype) that have enabled continued virtual communication throughout the pandemic [60] may affect the ability of PLWD to connect virtually with friends and family [59]. Having a poor Internet connection or not having help with setting up videoconferencing can worsen the experience of isolation for PLWD [17,27].

No specific methods for validating telehealth approaches were outlined in any of the articles included in this review. Given the longevity of the COVID-19 pandemic, the need to adjust dementia services delivered via telehealth may be necessary. As public emergency measures progress with COVID-19, the use of computer- or smartphone-based videoconference telehealth tools can also enable clinicians to assess home situations (e.g., safety assessments, medication storage and use) to prioritize allocation of limited in-home services and eventual clinic services once services can safely resume in person [61]. However, older adults may face significant barriers to using these services; one study reported that (as of March 2020) older adults aged 65 years and older were 42% less likely to use videoconference telehealth compared to adults aged 18–44 years. The authors of the study suggested that the younger population’s adaptability to and knowledge of technology for healthcare could be driving this difference in telehealth usage [58].

Furthermore, the feasibility of a rapid transition of dementia services to online platforms for PLWD who also live in rural or remote areas is largely unknown. Cognitive testing and satisfaction with telehealth among rural-dwelling PLWD have proven satisfactory among providers and PLWD when delivered from telemedicine centres [62]. However, certain populations of PLWD, such as those with advanced dementia, those with hearing or visual impairments and those who are not fluent in English, may face additional barriers to accessing these services [62].

To promote telehealth use among PLWD and to facilitate comfort with its use, Weiss et al. (2021), suggest first initiating services with a telephone call to create rapport between clinicians and PLWD and then progressing to computer or smartphone-based videoconferencing. Familiarity with technologies has also been found to facilitate uptake and increased use of telehealth interventions [37,39]. The importance of caregiver presence during telehealth sessions has been identified in another recent qualitative study of caregiver needs during COVID-19 which found that caregivers who are more knowledgeable and better equipped to use telehealth for dementia-related education would be better suited to implement therapies such as CST [61]. However, future research requires input from PLWD and their caregivers in the design and testing of such platforms.

There were limited findings on the impact of COVID-19 on mental health services and supports for PLWD and caregivers, yet concerns over caregiver burnout [47,49] and anxiety were commonly described [45,48]. After just two weeks of isolation, Goodman-Casanova et al. (2020) reported that PLWD had poorer mental health compared to baseline, including increases in fear, frustration and boredom and—for PLWD isolating alone—poorer sleep. With the reduction in community services and supports, such as exercise groups, social groups, pet therapy and other supports [17], isolation, loneliness and physical deconditioning may have been experienced by PLWD and caregivers. While connecting PLWD with social workers to reduce anxiety during the pandemic has been suggested, [41] the lack of mental health experts and Internet accessibility for PLWD may have exacerbated loss of contact and isolation [40].

Limitations

Given that the aim of this paper was to examine dementia-related community supports and services, exclusion of literature reporting on older adults without dementia may have missed valuable literature on alterations to services and supports in the community for older adults, including PLWD. The literature was also limited to English articles and high-income countries. The resulting identified articles in the time frame of this review (2000 to July 2020) on resources, supports and services for people living with dementia and their caregivers available during infectious respiratory disease outbreaks was limited to mainly commentary and editorial articles.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review identified literature describing general themes of reduced services and resources during the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, increased use and potential for telehealth services and brief commentary on the future impacts to PLWD and their caregivers of reduced in-person services. In the included articles, there was limited primary research or consideration of health equity during the reduction of services for PLWD during public health restrictions, which suggests there is still work to be done to ensure that equity considerations are explicitly included in disaster and emergency planning.

This rapid review demonstrates that there is a need for research exploring the health equity impact of service disruptions on PLWD. Such research would help guide planning for future public health emergencies to ensure the equitable development and implementation of resources to support PLWD and their caregivers. This will be important, as limitations to the online delivery of dementia resources and services were noted in multiple articles, including concerns over accessibility and feasibility among PLWD. The challenges that PLWD and caregivers face living in the community during public health emergencies are not well understood; future research examining the experiences of reduced essential services, such as home care [51], are necessary. Monitoring these impacts on PLWD and caregivers residing in the community can help to understand their unique, unmet needs using a health equity approach that considers gender, sexuality, ethnoracial and cultural community or living with disability to prevent further marginalization.

Recommendations for Research

This review supports the need for education among healthcare workers about the unique and complex situation of people living with dementia in the community during public health emergencies to ensure that they are not rendered invisible in future emergencies. Furthermore, it highlights the need to explicitly include equity considerations in disaster planning to include people living in the community with dementia and the need to recognize the existing barriers to supports and services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing was contributed to by all authors, K.M.B., E.M., K.A., M.S. and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

First author (K.M.B.) received a student Mitacs scholarship to complete this project. The project was also funded by the Nova Scotia COVID-19 Health Research Coalition.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors and can be provided upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Search Strategy

Table A1.

Ovid (Medline). Date of search: 7 July 2020.

Table A1.

Ovid (Medline). Date of search: 7 July 2020.

| No. | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | dementia/or alzheimer disease/ | 135,806 |

| 2 | (dementia or alzheimer?).ab,ti. | 212,532 |

| 3 | 1 and 2 | 231,370 |

| 4 | Public Health/ | 80,941 |

| 5 | community health nursing/or home health nursing/ | 19,929 |

| 6 | home care services/or home health nursing/or home nursing/or respite care/ | 41,793 |

| 7 | Community Health Workers/ | 5264 |

| 8 | (community or servic? or resourc? or help or aid or home care or assist * or outreach or support *).ti,ab. | 3,100,601 |

| 9 | 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 | 3,195,414 |

| 10 | epidemics/or pandemics/ | 24,716 |

| 11 | (pandemic or epidemic or coronavirus or COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2).ti,ab. | 146,742 |

| 12 | 10 or 11 | 150,491 |

| 13 | 3 and 9 and 12 | 150 |

Table A2.

Embase (Elsevier). Date of search: 7 July 2020.

Table A2.

Embase (Elsevier). Date of search: 7 July 2020.

| No. | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ‘dementia’/exp | 361,571 |

| 2 | ‘alzheimer disease’/exp | 199,089 |

| 3 | dementia OR alzheimer*:ti,ab | 342,207 |

| 4 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 | 423,341 |

| 5 | ‘community care’/exp | 124,840 |

| 6 | ‘public health’/exp | 188,564 |

| 7 | ‘home care’/de | 62,203 |

| 8 | ‘home visit’/de | 2842 |

| 9 | ‘visiting nursing service’/exp | 171 |

| 10 | (community OR servic? OR resourc? OR help OR aid OR home) AND care OR assist* OR outreach OR support*:ab,ti | 4,327,849 |

| 11 | #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 | 4,492,285 |

| 12 | ‘coronavirus disease 2019′/exp | 14,755 |

| 13 | ‘COVID-19′ OR coronavirus OR pandemic OR epidemic:ab,ti | 167,854 |

| 14 | ‘pandemic’/exp | 20,208 |

| 15 | ‘epidemic’/exp | 108,968 |

| 16 | #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 | 231,025 |

| 17 | #4 AND #11 AND #16 | 463 |

Table A3.

CINAHL. Date of search: 7 July 2020.

Table A3.

CINAHL. Date of search: 7 July 2020.

| No. | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (MH “Dementia”) OR (MH “Dementia, Presenile”) OR (MH “Dementia, Senile”) OR (MH “Alzheimer’s Disease”) | 73,515 |

| 2 | AB (dementia or alzheimer*) OR TI (dementia or alzheimer*) | 78,5083 |

| 3 | S1 OR S2 | 95,433 |

| 4 | (MH “Home Health Aides”) OR (MH “Home Health Care”) | 25,215 |

| 5 | (MH “Community Health Nursing”) OR (MH “Community Health Workers”) OR (MH “Community Health Services”) | 52,973 |

| 6 | AB (community or servic? or resourc? or help or aid or home care or assist* or outreach or support*) OR TI (community or servic? or resourc? or help or aid or home care or assist* or outreach or support*) | 1,021,735 |

| 7 | 4 OR 5 OR 6 | 1,056,717 |

| 8 | (MH “Coronavirus”) OR (MH “Coronavirus Infections”) | 2968 |

| 9 | AB (pandemic or epidemic or coronavirus or COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2) OR TI (pandemic or epidemic or coronavirus or COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2) | 39,292 |

| 10 | 8 OR 9 | 39,643 |

| 11 | 3 AND 7 AND 10 | 51 |

Appendix B

Table A4.

Grey literature articles identified with articles of interest.

Table A4.

Grey literature articles identified with articles of interest.

| Targeted Web Page Searches and Number of Articles Included in Screening | |

|---|---|

| Organization Name | Articles/Articles Found |

| Alzheimer Society of Canada | 3 |

| Alzheimer Society of Alberta and Northwest Territories | 2 |

| Alzheimer Society British Columbia | 5 |

| Alzheimer Society of New Brunswick | 2 |

| Alzheimer Society of Nova Scotia | 2 |

| Alzheimer Society of PEI | 1 |

| Alzheimer Society of Saskatchewan | 1 |

| Alzheimer’s Association | 1 |

| CEBM: The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine | 1 |

| Alzheimer’s Association | 2 |

| Centers for Disease Control | 1 |

| Alzheimer’s Society (UK) | 9 |

| Public Health Ontario | 1 |

| Alberta Health Services | 1 |

| British Columbia Ministry of Health | 1 |

| Saskatchewan Health Authority | 1 |

| PEI Health | 2 |

| Newfoundland Health | 2 |

| Alzheimer’s Society UK | 9 |

| UK Government | 4 |

| CADTH Databases Search with articles of interest Keywords: “dementia”, results manually scanned for relevance to SARS/MERS/COVID-19 | |

| Website/Database | Results |

| World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Observatory (GHO) http://www.who.int/gho/en/, (accessed on 25 July 2020). | 1 |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) FastStats A to Z http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/, (accessed on 25 July 2020). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/, (accessed on 25 July 2020). National Center for Health Statistics http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/, (accessed on 25 July 2020). | 2 |

| World Health Organization. International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal (ICTRP) http://www.who.int/trialsearch/, (accessed on 25 July 2020). | 1 |

| Advanced google search Key words searched in title: “dementia COVID-19” “dementia SARS” “dementia MERS” | |

| Australia | 3 |

| Canada | 4 |

| Ireland | 5 |

| New Zealand | 6 |

| United Kingdom | 23 |

| United States | 4 |

Appendix C

Table A5.

Extraction Instrument.

Table A5.

Extraction Instrument.

| Information to Be Extracted | ||

|---|---|---|

| Title | ||

| Author(s) Or Organization | ||

| Year, month of publication (month relevant to progression of pandemic) | ||

| Citation information | ||

| Origin (country), province/region | ||

| Type of literature (research [include if thesis] or grey Lit [type]) | ||

| Aim/purpose | ||

| Design/methods | ||

| Study population | ||

| Type of Infectious disease/Pandemic (e.g., COVID, SARS) | ||

| Restrictions in place (e.g., social isolation) | ||

| Target group or group that received Services/Resources in article (e.g., PLWD and/or caregivers) | ||

| Resources and Services Identified: | Category | Details (include details about changes to services availability during COVID) |

| Transportation | ||

| Essential delivery services (e.g., groceries) | ||

| Home care—formal/regulated providers (community nursing, CCA, etc) | ||

| Home care—informal providers—family, friends) | ||

| Online resources about pandemic (e.g., general knowledge about COVID) | ||

| telehealth | ||

| Medical equipment (e.g., PPE, oxygen) | ||

| Medication and medication management (e.g., medication delivery) | ||

| Respite | ||

| Community-based Social resources and leisure activities (e.g., support groups) | ||

| Infection testing | ||

| Mental health (for caregivers and/or PLWD) | ||

| Other (specify) | ||

| Other (specify) | ||

| Other (specify) | ||

| Population (individuals who may experience significant unintended health impacts (positive or negative) as a result of services/resources impacted by COVID) | SDOH (determinants and health inequities to be considered alongside the populations identified) | Potential impacts on PLWD and/or caregivers. |

| Indigenous Peoples (e.g., First Nations, Inuit, Métis, etc.) | ||

| Disability (e.g., physical, D/deaf, deafened or hard of hearing, visual, intellectual/developmental, learning, mental illness, addictions/substance use, etc.) | ||

| Ethno-racial communities (e.g., racial/racialized or cultural minorities, immigrants and refugees, etc.) | ||

| Low income (e.g., unemployed, underemployed, etc.) | ||

| Religious/faith communities | ||

| Rural/remote or inner-urban populations (e.g., geographic/social isolation, under-serviced areas, etc.) | ||

| Sex/gender (e.g., male, female, women, men, trans, transsexual, transgendered, two-spirited, etc.) | ||

| Sexual orientation (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, etc.) | ||

| Other | ||

| Other | ||

| Other | ||

Template adapted from Gov of Ontario’s Health Equity Impact Assessment (HEIA) Workbook: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/heia/docs/workbook.pdf, (accessed on 9 November 2020).

References

- World Health Organization. Rolling Updates on Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. Available online: https://www.globaldiasporanews.com/health-equity-considerations-and-racial-and-ethnic-minority-groups/ (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Public Health Agency of Canada. From Risk to Resilience: An Equity Approach to COVID-19; The Chief Public Health Officer of Canada’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2020; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020; 86p. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19.html#a1.4 (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- Kucharczyk, M. COVID-19 and Human Rights Concerns for Older Persons; AGE Platform Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; 33p, Available online: https://www.age-platform.eu/sites/default/files/Human_rights_concerns_on_implications_of_COVID-19_to_older_persons_Final_18May2020.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Worst Hit: Dementia during Coronavirus; Alzheimer’s Society: London, UK, 2020; 49p, Available online: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-09/Worst-hit-Dementia-during-coronavirus-report.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Armitage, R.; Nellums, L.B. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CIHI. Long-Term Care and COVID-19: The First 6 Months. 2021. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/long-term-care-and-covid-19-the-first-6-months#refi (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Government of Canada. Dementia in Canada, including Alzheimer’s Disease: Highlights from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017; 6p. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/dementia-highlights-canadian-chronic-disease-surveillance.html (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; 260p, Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf;jsessionid=7EF05867A827A34D2E6696F993946E03?sequence=1 (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Dementia in Canada; Canadian Institute for Health Information: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018; Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/dementia-in-canada/dementia-across-the-health-system/dementia-in-home-and-community-care (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Victor, C.R.; Rippon, I.; Nelis, S.M.; Martyr, A.; Litherland, R.; Pickett, J.; Hart, N.; Henley, J.; Matthews, F.; Clare, L. Prevalence and determinants of loneliness in people living with dementia: Findings from the IDEAL programme. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 35, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Dementia Strategy for Canada: Together We Aspire: In Brief; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019; 16p. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/dementia-strategy-brief.html (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Alzheimer Society of Canada. Responsive and Reactive Behaviours. Available online: http://alzheimer.ca/en/help-support/im-caring-person-living-dementia/understanding-symptoms/responsive-reactive-behaviours (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Park, M.; Sung, M.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.Y. Multidimensional determinants of family caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Dementia Priority Setting Partnership Steering Committee. Canadian Dementia Research Priorities: Report of the Canadian Dementia Priority Setting Partnership. 2017. Available online: https://archive.alzheimer.ca/sites/default/files/2018-01/Dementia%20PSP%20Report%20ENG%20Dec%20Final%20SCREEN_0.pdf?_ga=2.201138734.1228404274.1604943998-57021660.1604943998 (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Warrick, N.; Prorok, J.C.; Seitz, D. Care of community-dwelling older adults with dementia and their caregivers. CMAJ 2018, 190, E794–E799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, E.E.; Kumar, S.; Rajji, T.K.; Pollock, B.G.; Mulsant, B.H. Anticipating and Mitigating the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Health Equity Impact Assessment (HEIA) Workbook. Government of Ontario, 2012. Available online: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/heia/docs/template.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Nguyen, T.; Li, X. Understanding public-stigma and self-stigma in the context of dementia: A systematic review of the global literature. Dementia 2020, 19, 148–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Alzheimer Report 2019: Attitudes to Dementia; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2019; 160p, Available online: https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2019.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Kenning, C.; Daker-White, G.; Blakemore, A.; Panagioti, M.; Waheed, W. Barriers and facilitators in accessing dementia care by ethnic minority groups: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bayly, M.; Morgan, D.; Froehlich Chow, A.; Kosteniuk, J.; Elliot, V. Dementia-Related Education and Support Service Availability, Accessibility, and Use in Rural Areas: Barriers and Solutions. Can. J. Aging. 2020, 39, 545–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sivananthan, S.N.; Lavergne, M.R.; McGrail, K.M. Caring for dementia: A population-based study examining variations in guideline-consistent medical care. Alzheimers Dement. 2015, 11, 906–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieber, A.; Nguyen, N.; Meyer, G.; Stephan, A. Influences on the access to and use of formal community care by people with dementia and their informal caregivers: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, D. ‘Age and ageism in COVID-19′: Elderly mental health-care vulnerabilities and needs. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 51, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prospero. A Meta-Analysis of the Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Wellbeing of Elderly Population. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020185409 (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Prospero. Drawing on Wisdom to Cope with Adversity: A Systematic Review Protocol of Older Adults Mental and Psychosocial Health during Acute Respiratory Disease Propagated-Type Epidemics and Pandemics (COVID-19, SARS-CoV, MERS, and Influenza). Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD420201900592020 (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Prospero. The Frailty Assessment as a Predictor of Mortality and Adverse Outcomes in Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020189132 (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Prospero. What Are the Mental Health Impacts of Infectious Disease Epidemics on Relatives and Informal Carers of Affected Individuals, and on Relatives of Health Workers, and What Interventions Are Available to Support Them? Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020184134 (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11 Scoping Reviews. In JBI Reviewer’s Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, V.; Petticrew, M.; Tugwell, P.; Moher, D.; O’Neill, J.; Waters, E.; White, H.; The PRISMA-Equity Bellagio Group. PRISMA-Equity 2012 extension: Reporting guidelines for systematic reviews with a focus on health equity. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. SARS Basics Factsheet. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/sars/about/fs-sars.html (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Grey Matters: A Practical Tool for Searching Health-Related Grey Literature. Available online: https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/grey-matters (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- The World Bank. High Income. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country/XD (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Canevelli, M.; Bruno, G.; Cesari, M. Providing Simultaneous COVID-19-sensitive and Dementia-Sensitive Care as We Transition from Crisis Care to Ongoing Care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 968–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuffaro, L.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Bonavita, S.; Tedeschi, G.; Leocani, L.; Lavorgna, L. Dementia care and COVID-19 pandemic: A necessary digital revolution. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 1977–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devita, M.; Bordignon, A.; Sergi, G.; Coin, A. The psychological and cognitive impact of Covid-19 on individuals with neurocognitive impairments: Research topics and remote intervention proposals. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, G.; Peri, K. Challenges to dementia care during COVID-19: Innovations in remote delivery of group Cognitive Stimulation Therapy. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 977–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachana, N.A.; Beattie, E.; Byrne, G.J.; Brodaty, H. COVID-19 and psychogeriatrics: The view from Australia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, Y.F.; Wan, W.H.; Chan, M.M.K.; DeKosky, S.T. Time-to-change: Dementia care in COVID-19. Psychogeriatrics 2020, 20, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, E. Remembering people with dementia during the COVID-19 crisis. HRB Open Res. 2020, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Canevelli, M.; Valletta, M.; Toccaceli Blasi, M.; Remoli, G.; Sarti, G.; Nuti, F.; Sciancalepore, F.; Ruberti, E.; Cesari, M.; Bruno, G. Facing Dementia During the COVID-19 Outbreak. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1673–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Casanova, J.M.; Dura-Perez, E.; Guzman-Parra, J.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.; Mayoral-Cleries, F. Telehealth Home Support During COVID-19 Confinement for Community-Dwelling Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Mild Dementia: Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, P.; Zwiers, A.; Cox, E.; Fischer, K.; Charlton, A.; Josephson, C.B.; Patten, S.B.; Seitz, D.; Ismail, Z.; Smith, E.E. Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on well-being and virtual care for people living with dementia and care partners living in the community. Dementia 2021, 20, 2007–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochford-Brennan, H.; Keogh, F. Giving voice to those directly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic—the experience and reflections of a person with dementia. HRB Open Res. 2020, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fermín, M.C.; U.S. National Library of Medicine. Cognitive Outcomes during COVID-19 confiNemeNt in Elderly and Their Caregivers Using Technologies for DEMentia. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04385797 (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- National Health Service. COVID-19 and Dementia: MAS Service, Activity and Learning, in Wessex and Thames Valley; National Health Service: London, UK, 2020; 12p. Available online: https://www.hampshirethamesvalleyclinicalnetworks.nhs.uk/download/covid-19-dementia-mas-service/ (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- LLoyd-Williams, M.; Mogan, C.; Russell, S.; Harrison-Dening, K. Activities Delivered at Home by Family Carers to Maintain Cognitive Function in People with Dementia Socially Isolating during COVID-19: Evidence for Non-Technology Based Activities/Interventions. CEBM Website. Available online: https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/activities-delivered-at-home-by-family-carers-to-maintain-cognitive-function-in-people-with-dementia-socially-isolating-during-covid-19-evidence-for-non-technology-based-activities-inte/ (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Lai, F.H.; Yan, E.W.; Yu, K.K.; Tsui, W.S.; Chan, D.T.; Yee, B.K. The Protective Impact of Telemedicine on Persons With Dementia and Their Caregivers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, M.K.; Tierney, M.C. The puzzle of sex, gender and Alzheimer’s disease: Why are women more often affected than men? Womens Health 2018, 14, 1745506518817995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chin, A.L.; Negash, S.; Hamilton, R. Diversity and disparity in dementia: The impact of ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2011, 25, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Babulal, G.M.; Quiroz, Y.T.; Albensi, B.C.; Arenaza-Urquijo, E.; Astell, A.J.; Babiloni, C.; Bahar-Fuchs, A.; Bell, J.; Bowman, G.L.; Brickman, A.M.; et al. Perspectives on ethnic and racial disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Update and areas of immediate need. Alzheimers Dement. 2019, 15, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrecht, K.; Kelly, C.; Rice, C. (Eds.) The Aging–Disability Nexus; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.J. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on vulnerable older adults in the United States. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2020, 63, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.; Crameri, P.; Lambourne, S.; Latham, J.R.; Whyte, C. Understanding the experiences and needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans Australians living with dementia, and their partners. Australas J. Ageing. 2015, 34 (Suppl. 2), 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basoudan, N.; Tales, A. COVID-19 and Dementia: A Review and synthesis of material on a deadly combination. Neurophysiol. Rehabil. 2020, 3, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, D.H.; Lee, L.; Huynh, S.; Haskell, T.P. Health Inequalities in the Use of Telehealth in the United States in the Lens of COVID-19. Popul. Health Manag. 2020, 23, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Commission for Social Development. More Must Be Done to Close Digital Divide, End Poverty, Speakers Say, as Social Development Commission Continues Debate. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/soc4895.doc.htm. (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- McDonough, C.C. The Effect of Ageism on the Digital Divide Among Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2016, 2, 008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weiss, E.F.; Malik, R.; Santos, T.; Ceide, M.; Cohen, J.; Verghese, J.; Zwerling, J.L. Telehealth for the cognitively impaired older adult and their caregivers: Lessons from a coordinated approach. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2021, 11, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhon, H.; Sekhon, K.; Launay, C.; Afililo, M.; Innocente, N.; Vahia, I.; Rej, S.; Beauchet, O. Telemedicine and the rural dementia population: A systematic review. Maturitas 2021, 143, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).